Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Japanese castle

View on Wikipedia

Japanese castles (城, shiro or jō) are fortresses constructed primarily of wood and stone. They evolved from the wooden stockades of earlier centuries and came into their best-known form in the 16th century. Castles in Japan were built to guard important or strategic sites, such as ports, river crossings, or crossroads, and almost always incorporated the landscape into their defenses.

Though they were built to last and used more stone in their construction than most Japanese buildings, castles were still constructed primarily of wood, and many were destroyed over the years. This was especially true during the Sengoku period (1467–1603), when many of these castles were first built. However, many were rebuilt, either later in the Sengoku period, in the Edo period (1603–1867) that followed, or more recently, as national heritage sites or museums. Today there are more than one hundred castles extant, or partially extant, in Japan; it is estimated that once there were five thousand.[1] Some castles, such as the ones at Matsue and Kōchi, both built in 1611, have main keeps or other buildings that remain extant in their historical forms, not having suffered any damage from sieges or other threats. Hiroshima Castle, on the opposite end of the spectrum, was destroyed in the atomic bombing, and was rebuilt in 1958 as a museum, though it does retain many of its original stone walls.[2]

The character for castle, '城', is pronounced shiro (its kun'yomi) when used as a standalone word. However, when attached to another word (such as in the name of a particular castle), it is read as jō (its Chinese-derived on'yomi). Thus, for example, Osaka Castle is called Ōsaka-jō (大阪城) in Japanese.

History

[edit]

Originally conceived as fortresses for military defense, Japanese castles were placed in strategic locations, typically along trade routes, roads, and rivers. Though castles continued to be built with these considerations, for centuries, fortresses were also built as centres of governance. By the Sengoku period, they had come to serve as the homes of daimyo (大名, feudal lords), to impress and to intimidate rivals not only with their defences but also with their sizes, architecture, and elegant interiors. In 1576, Oda Nobunaga was among the first to build one of these palace-like castles: Azuchi Castle was Japan's first castle to have a tenshu (天守, main keep), and it inspired both Toyotomi Hideyoshi's Osaka Castle and Tokugawa Ieyasu's Edo Castle.[3] Azuchi served as the governing center of Oda's territories, and as his lavish home, but it was also very keenly and strategically placed. A short distance away from the capital of Kyoto, which had long been a target of violence, Azuchi's carefully chosen location allowed it a great degree of control over the transportation and communication routes of Oda's enemies.

The tenshu (main keep) was used as a storehouse in times of peace and as a fortified tower in times of war, and the daimyo (feudal lords)'s government offices and residences were located in a group of single-story buildings near the tenshu and the surrounding yagura (櫓, turrets). The only exception was Oda Nobunaga's Azuchi-Momoyama Castle, where he lived in the tenshu (main keep).[4]

Before the Sengoku period (roughly the 16th century), most castles were called yamajirō (山城, 'mountain castles'). Though most later castles were built atop mountains or hills, these were built from the mountains.[5] Trees and other foliage were cleared, and the stone and dirt of the mountain itself was carved into rough fortifications. Ditches were dug, to present obstacles to attackers, as well as to allow boulders to be rolled down at attackers. Moats were created by diverting mountain streams. Buildings were made primarily of wattle and daub, using thatched roofs, or, occasionally, wooden shingles. Small ports in the walls or planks could be used to deploy bows or fire guns from. The main weakness of this style was its general instability. Thatch caught fire even more easily than wood, and weather and soil erosion prevented structures from being particularly large or heavy. Eventually, stone bases began to be used, encasing the hilltop in a layer of fine pebbles, and then a layer of larger rocks over that, with no mortar.[5] This support allowed larger, heavier, and more permanent buildings.

Early fortifications

[edit]

The first fortifications in Japan were hardly what one generally associates with the term "castles". Made primarily of earthworks, or rammed earth, and wood, the earliest fortifications made far greater use of natural defences and topography than anything human-made. These kōgoishi and chashi (チャシ, for Ainu castles) were never intended to be long-term defensive positions, let alone residences; the native peoples of the archipelago built fortifications when they were needed and abandoned the sites afterwards.

The Yamato people began to build cities in earnest in the 7th century, complete with expansive palace complexes, surrounded on four sides with walls and impressive gates. Earthworks and wooden fortresses were also built throughout the countryside to defend the territory from the native Emishi, Ainu and other groups; unlike their primitive predecessors, these were relatively permanent structures, built in peacetime. These were largely built as extensions of natural features, and often consisted of little more than earthworks and wooden barricades.

The Nara period (c. 710–794) fortress at Dazaifu, from which all of Kyūshū would be governed and defended for centuries afterwards, was originally constructed in this manner, and remnants can still be seen today. A bulwark was constructed around the fortress to serve as a moat to aid in the defense of the structure; in accordance with military strategies and philosophies of the time, it would only be filled with water at times of conflict. This was called a mizuki (水城), or "water fort".[6] The character for castle or fortress (城), up until sometime in the 9th century or later, was read (pronounced) ki, as in this example, mizuki.[citation needed]

Though fairly basic in construction and appearance, these wooden and earthwork structures were designed to impress just as much as to function effectively against attack. Chinese and Korean architecture influenced the design of Japanese buildings, including fortifications, in this period. The remains or ruins of some of these fortresses, decidedly different from what would come later, can still be seen in certain parts of Kyūshū and Tōhoku today.

Medieval period

[edit]The Heian period (794–1185) saw a shift from the need to defend the entire state from invaders to that of lords defending individual mansions or territories from one another. Though battles were still continually fought in the north-east portion of Honshū (the Tōhoku region) against native peoples, the rise of the samurai warrior class[Notes 1] towards the end of the period, and various disputes between noble families jostling for power and influence in the Imperial Court brought about further upgrades. The primary defensive concern in the archipelago was no longer native tribes or foreign invaders, but rather internal conflicts within Japan, between rival samurai clans or other increasingly large and powerful factions, and as a result, defensive strategies and attitudes were forced to change and adapt. As factions emerged and loyalties shifted, clans and factions that had helped the Imperial Court became enemies, and defensive networks were broken, or altered through the shifting of alliances.

The Genpei War (1180–1185) between the Minamoto and Taira clans, and the Nanboku-chō Wars (1336–1392) between the Northern and Southern Imperial Courts are the primary conflicts that define these developments during what is sometimes called Japan's medieval period.

Fortifications were still made almost entirely out of wood, and were based largely on earlier modes, and on Chinese and Korean examples. But they began to become larger, to incorporate more buildings, to accommodate larger armies, and to be conceived as more long-lasting structures. This mode of fortification, developed gradually from earlier modes and used throughout the wars of the Heian period (770–1185), and deployed to help defend the shores of Kyūshū from the Mongol invasions of the 13th century,[Notes 2] reached its climax in the 1330s, during the Nanboku-chō period. Chihaya Castle and Akasaka castle, permanent castle complexes containing a number of buildings but no tall keep towers, and surrounded by wooden walls, were built by Kusunoki Masashige to be as militarily effective as possible, within the technology and designs of the time.

The Ashikaga shogunate, established in the 1330s, had a tenuous grip on the archipelago, and maintained relative peace for over a century. Castle design and organization continued to develop under the Ashikaga shogunate, and throughout the Sengoku period. Castle complexes became fairly elaborate, containing a number of structures, some of which were quite complex internally, as they now served as residences, command centres, and a number of other purposes.

Sengoku

[edit]

The Ōnin War, which broke out in 1467, marked the beginning of 147 years of widespread warfare (called the Sengoku period) between daimyōs (feudal lords) across the entire archipelago. For the duration of the Ōnin War (1467–1477), and into the Sengoku period, the entire city of Kyoto became a battlefield, and suffered extensive damage. Noble family mansions across the city became increasingly fortified over this ten-year period, and attempts were made to isolate the city as a whole from the marauding armies of samurai that dominated the landscape for over a century.[7]

As regional officials and others became the daimyōs, and the country descended into war, they began to quickly add to their power bases, securing their primary residences, and constructing additional fortifications in tactically advantageous or important locations. Originally conceived as purely defensive (martial) structures, or as retirement bunkers where a lord could safely ride out periods of violence in his lands, over the course of the Sengoku period, many of these mountain castles developed into permanent residences, with elaborate exteriors and lavish interiors.

The beginnings of the shapes and styles now considered to be the "classic" Japanese castle design emerged at this time, and castle towns (jōkamachi, "town below castle") also appeared and developed. Despite these developments, though, for most of the Sengoku period castles remained essentially larger, more complex versions of the simple wooden fortifications of centuries earlier. It was not until the last thirty years of the period of war that drastic changes would occur to bring about the emergence of the type of castle typified by Himeji Castle and other surviving castles. This period of war culminated in the Azuchi–Momoyama period, the scene of numerous fierce battles, which saw the introduction of firearms and the development of tactics to employ or counter them.

Azuchi–Momoyama period

[edit]

Unlike in Europe, where the advent of the cannon spelled the end of the age of castles, Japanese castle-building was spurred, ironically, by the introduction of firearms.[3] Though firearms first appeared in Japan in 1543, and castle design almost immediately saw developments in reaction, Azuchi castle, built in the 1570s, was the first example of a largely new type of castle, on a larger, grander scale than those that came before, boasting a large stone base (武者返し, musha-gaeshi), a complex arrangement of concentric baileys (丸, maru), and a tall central tower. In addition, the castle was located on a plain, rather than on a densely forested mountain, and relied more heavily on architecture and manmade defenses than on its natural environment for protection. These features, along with the general appearance and organization of the Japanese castle, which had matured by this point, have come to define the stereotypical Japanese castle. Along with Hideyoshi's Fushimi–Momoyama castle, Azuchi lends its name to the brief Azuchi–Momoyama period (roughly 1568–1600) in which these types of castles, used for military defense, flourished.

Osaka Castle was destroyed by cannon. This reproduction of its donjon towers above the surroundings. The introduction of the arquebus brought dramatic shifts in battle tactics and military attitudes in Japan. Though these shifts were complex and numerous, one of the concepts key to changes in castle design at this time was that of battle at range. Though archery duels had traditionally preceded samurai battles since the Heian period or earlier, exchanges of fire with arquebuses had a far more dramatic effect on the outcome of the battle; hand-to-hand fighting, while still very common, was diminished by the coordinated use of firearms.

Oda Nobunaga, one of the most expert commanders in the coordinated tactical use of the new weapon, built his Azuchi castle, which has since come to be seen as the paradigm of the new phase of castle design, with these considerations in mind. The stone foundation resisted damage from arquebus balls better than wood or earthworks, and the overall larger scale of the complex added to the difficulty of destroying it. Tall towers and the castle's location on a plain provided greater visibility from which the garrison could employ their guns, and the complex set of courtyards and baileys provided additional opportunities for defenders to retake portions of the castle that had fallen.[8]

Cannon were rare in Japan due to the expense of obtaining them from foreigners, and the difficulty in casting such weapons themselves as the foundries used to make bronze temple bells were simply unsuited to the production of iron or steel cannon. The few cannon that were used were smaller and weaker than those used in European sieges, and many of them were in fact taken from European ships and remounted to serve on land; where the advent of cannon and other artillery brought an end to stone castles in Europe, wooden ones would remain in Japan for several centuries longer. A few castles boasted 'wall guns', but these are presumed to have been little more than large caliber arquebuses, lacking the power of a true cannon. When siege weapons were used in Japan, they were most often trebuchets or catapults in the Chinese style, and they were used as anti-personnel weapons.[5] There is no record that the goal of destroying walls ever entered into the strategy of a Japanese siege. In fact, it was often seen to be more honorable, and more tactically advantageous on the part of the defender for him to lead his forces into battle outside the castle.[citation needed] When battles were not resolved in this way, out in the open, sieges were almost always undertaken purely by denying supplies to the castle, an effort that could last years, but involved little more than surrounding the castle with a force of sufficient size until a surrender could be elicited.

The crucial development that spurred the emergence of a new type of defensive architecture was, thus, not cannon, but the advent of firearms. Arquebus firing squads and cavalry charges could overcome wooden stockades with relative ease, and so stone castles came into use.

Azuchi Castle was destroyed in 1582, just three years after its completion, but it nevertheless ushered in a new period of castle-building. Among the many castles built in the ensuing years was Hideyoshi's castle at Osaka, completed in 1585. This incorporated all the new features and construction philosophies of Azuchi, and was larger, more prominently located, and longer-lasting. It was the last bastion of resistance against the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate (see Siege of Osaka), and remained prominent if not politically or militarily significant, as the city of Osaka grew up around it, developing into one of Japan's primary commercial centers.

This period saw the climax of earlier developments towards larger buildings, more complex and concentrated construction, and more elaborate design, both externally and in the castles' interiors. European castle design began to have an impact as well in this period, though the castle had long been in decline in Europe by this point.

In Japanese politics and warfare, the castle served not only as a fortress, but as the residence of the daimyō (feudal lord), and as a symbol of his power. Fushimi Castle, which was meant to serve as a luxurious retirement home for Toyotomi Hideyoshi, serves as a popular example of this development. Though it resembled other castles of the period on the outside, the inside was lavishly decorated, and the castle is famous for having a tea room covered in gold leaf. Fushimi was by no means an exception, and many castles bore varying amounts of golden ornamentation on their exteriors. Osaka castle was only one of a number of castles that boasted golden roof tiles, and sculptures of fish, cranes, and tigers. Certainly, outside of such displays of precious metals, the overall aesthetics of the architecture and interiors remained very important, as they do in most aspects of Japanese culture.

Some especially powerful families controlled not one, but a whole string of castles, consisting of a main castle (honjō) and a number of satellite castles (shijō) spread throughout their territory. Though the shijō were sometimes full-fledged castles with stone bases, they were more frequently fortresses of wood and earthenworks. Often, a system of fire beacons, drums, or conch shells was set up to enable communications between these castles over a great distance. The Hōjō family's Odawara Castle and its network of satellites was one of the most powerful examples of this honjō-shijō system; the Hōjō controlled so much land that a hierarchy of sub-satellite networks was created[9]

Korea

[edit]Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea took place between 1592 and 1598, at the same time as the high point in Azuchi–Momoyama style castle construction within Japan. Many Japanese castles (called Wajō 倭城 in Japanese and Waeseong in Korean) were built along the southern shores of Korea. All that remains of these castles today are the stone bases.

Edo period

[edit]

The Sengoku period, roughly a century and a half of war that brought great changes and developments in military tactics and equipment, as well as the emergence of the Azuchi-Momoyama style castle, was followed by the Edo period, over two hundred and fifty years of peace, beginning around 1600–1615 and ending in 1868. Edo period castles, including survivors from the preceding Azuchi-Momoyama period, therefore no longer had defense against outside forces as their primary purpose. Rather, they served primarily as luxurious homes for the daimyōs, their families and retainers, and to protect the daimyō, and his power base, against peasant uprisings and other internal insurrections. The Tokugawa shogunate, to forestall the amassing of power on the part of the daimyōs, enforced a number of regulations limiting the number of castles to one per han (feudal domain), with a few exceptions especially the ones the ones in Satsuma and the ones up north ,[Notes 3][11] and a number of other policies including that of sankin-kōtai. Though there were also, at times, restrictions on the size and furnishings of these castles, and although many daimyōs grew quite poor later in the period, daimyō nevertheless sought as much as possible to use their castles as representations of their power and wealth. The general architectural style did not change much from more martial times, but the furnishings and indoor arrangements could be quite lavish.

This restriction on the number of castles allowed each han had profound effects not only politically, as intended, but socially, and in terms of the castles themselves. Where members of the samurai class had previously lived in or around the great number of castles sprinkling the landscape, they now became concentrated in the capitals of the han and in Edo; the resulting concentration of samurai in the cities, and their near-total absence from the countryside and from cities that were not feudal capitals (Kyoto and Osaka in particular) were important features of the social and cultural landscape of the Edo period. Meanwhile, the castles in the han capitals inevitably expanded, not only to accommodate the increased number of samurai they now had to support, but also to represent the prestige and power of the daimyō, now consolidated into a single castle. Edo castle, expanded by a factor of twenty between roughly 1600 and 1636 after becoming the shogunal seat. Though obviously something of an exception, the shōgun not being a regular daimyō, it nevertheless serves as a fine example of these developments. These vastly consolidated and expanded castles, and the great number of samurai living, by necessity, in and around them, thus led to an explosion in urban growth in 17th century Japan.[citation needed]

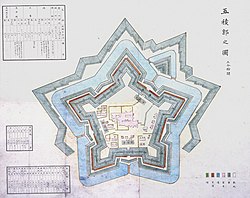

As contact with Western powers increased in the middle of the 19th century, some castles such as Goryōkaku in Hokkaidō were turned once again to martial purposes. No longer needed to resist samurai cavalry charges, or arquebus squads, attempts were made to convert Goryōkaku, and a handful of other castles across the country, into defensible positions against the cannon of Western naval vessels.

Modern period

[edit]

Meiji Restoration

[edit]Before the feudal system could be completely overturned, castles played a role in the initial resistance to the Meiji Restoration. In January 1868, the Boshin War broke out in Kyoto, between samurai forces loyal to the disaffected Bakufu government, and allied forces loyal to the new Meiji Emperor, which consisted mainly of samurai and rōnin from the Choshu and Satsuma domains.[12] By January 31, the Bakufu army had retreated to Osaka Castle in disarray and the shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu had fled to Edo (later Tokyo).[13] Osaka Castle was surrendered to the Imperial forces without a fight, and on February 3, 1868, many of the buildings of Osaka Castle were burned. The heavy damage to Osaka Castle, which was a significant symbol of the power of the Shogun in western Japan, dealt a major blow to the prestige of the shogunate and the morale of their troops.

From Edo, the Bakufu forces fled north to the Aizu domain, from whence a large number of their troops hailed. As the Aizu Campaign opened, Nagaoka and Komine Castles were the scenes of heavy fighting.[14] In the course of battle, Komine Castle was burned (it was re-built in 1994). The allied forces continued north to the city of Wakamatsu, and lay siege to Tsuruga Castle. After a month, with the walls and main tower pock-marked by bullets and cannonballs, Tsuruga Castle was finally surrendered. Its buildings were later demolished or moved, with some of them being rebuilt starting in 1965.

From Aizu, some Bakufu loyalists made their way north to the city of Hakodate, on Hokkaido. There they set up the Republic of Ezo, centered on a government building within the walls of Goryōkaku, a French-style star fortress, which is nonetheless often included in lists and in literature on Japanese castles. After the fierce Battle of Hakodate, the fortress of Goryōkaku was under siege, and finally surrendered on May 18, 1869, bringing an end to the Boshin War.[15]

All castles, along with the feudal domains themselves, were turned over to the Meiji government in the 1871 abolition of the han system. During the Meiji Restoration, these castles were viewed as symbols of the previous ruling elite, and nearly 2,000 castles were dismantled or destroyed. Others were simply abandoned and eventually fell into disrepair.[16]

Rebellions continued to break out during the first years of the Meiji period. The last and largest was the Satsuma Rebellion (1877). After heated disagreements in the new Tokyo legislature, young former samurai of the Satsuma domain rashly decided to rebel against the new government, and lobbied Saigō Takamori to lead them. Saigo reluctantly accepted and led Satsuma forces north from Kagoshima city. Hostilities commenced on February 19, 1877, when the defenders of Kumamoto Castle fired on the Satsuma troops. Fierce hand to hand combat gave way to a siege, but by April 12, reinforcements of the Imperial army arrived to break the siege. After a series of battles, the Satsuma rebels were forced back to Kagoshima city. Fighting continued there, and the stones walls of Kagoshima Castle still show the damage done by bullets. (Portions of the stone walls and the moat were left intact, and later the prefectural history museum was built on the castle's foundation.) The rebel force made their last stand on Shiroyama, or "Castle Mountain", probably named for a castle built there some time in the past, whose name has been lost in history. During the final battle, Saigo was mortally wounded, and the last forty rebels charged the Imperial troops and were cut down by Gatling guns. The Satsuma Rebellion came to an end at the Battle of "Castle Mountain" on the morning of September 25, 1877.

Imperial Japanese Army

[edit]Some castles, especially the larger ones, were used by the Imperial Japanese Army. Osaka Castle served as the headquarters for the 4th Infantry Division, until public funds paid for the construction of a new headquarters building within the castle grounds and a short distance from the main tower, so that the castle could be enjoyed by the citizens and visitors of Osaka. Hiroshima Castle served as Imperial General Headquarters during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and later as the headquarters for the 5th Infantry Division; Kanazawa Castle served as HQ for the 9th Infantry Division. For this reason, and as a way to strike against the morale and culture of the Japanese people, many castles were intentionally bombed during World War II. The main towers of the castles at Nagoya, Okayama, Fukuyama, Wakayama, Ōgaki, among others, were all destroyed during air raids. Hiroshima Castle is notable for having been destroyed in the atomic bomb blast on August 6, 1945. It was also on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle that news of the atomic bombing was first transmitted to Tokyo. When the atomic bomb detonated, a team of volunteer high school girls had just taken their shift on a radio in a small fortified bunker in the main courtyard of Hiroshima Castle. The girls transmitted the message that the city had been destroyed, to the confused disbelief of the officers receiving the message in Tokyo.

Shuri Castle (actually a Ryukyuan gusuku), on Okinawa Island was not only the headquarters for the 32nd Army and the defense of Okinawa, but also has the distinction of the being the last castle in Japan attacked by an invading force. In April 1945, Shuri Castle was the coordinating point for a line of outposts and defensive positions known as the "Shuri Line". US Soldiers and Marines encountered fierce resistance and hand-to-hand combat all along the Shuri Line. Starting on May 25, the castle was subjected to three days of intense naval bombardment from the USS Mississippi. On May 28, a company of US Marines took the castle, finding that the intensity of the destruction had prompted the headquarters contingent to abandon the castle and link up with scattered units and continue the defense of the island.[17] On May 30, the US flag was raised over one of the parapets of the castle. Shuri Castle was re-built in 1992, and is now an UNESCO World Heritage Site. Over 4,000 square metres (43,000 sq ft) of the Shuri Castle were burnt down due to an electrical fault on 30 October 2019 at around 2.34 am.[18]

Reconstruction and conservation

[edit]During the early 20th century, a new movement for the preservation of heritage grew. The first law for the preservation of sites of historical or cultural significance was enacted in 1919, and was followed ten years later by the 1929 National Treasure Preservation Law.[19][20] With the enactment of these laws, local governments had an obligation to prevent any further destruction, and they had some of the funds and resources of the national government to improve on these historically significant sites.

By the 1920s, nationalism was on the rise, and a new pride was found in the castles, which became symbols of Japan's warrior traditions.[21] With new advances in construction, some of the previously destroyed castle buildings were re-built quickly and cheaply with steel-reinforced concrete, such as the main tower of Osaka Castle, which was first re-built in 1928.

While many of the remaining castles in Japan are reconstructions or a mix of reconstructed and historical buildings, and many of the reconstructed buildings are steel-reinforced concrete replicas, there has been a movement toward traditional methods of construction. Kanazawa Castle is a remarkable example of a modern reproduction using a significant degree of traditional construction materials and techniques. Modern construction materials at Kanazawa Castle are minimal, discreet, and are primarily in place to ensure stability, safety concerns, and accessibility. At present, there are local non-profit associations that are attempting to collect funds and donations for the historically accurate re-construction of the main towers at Takamatsu Castle on Shikoku, and Edo Castle in Tokyo.

There are only twelve castles with main keeps that are considered "extant" (Japanese 'genson'), although many other castles have significant numbers of other extant historical castle buildings:[16]

- Bitchū Matsuyama Castle

- Hikone Castle

- Himeji Castle

- Hirosaki Castle

- Inuyama Castle

- Kōchi Castle

- Marugame Castle

- Maruoka Castle

- Matsue Castle

- Matsumoto Castle

- Matsuyama Castle (Iyo)

- Uwajima Castle

Most of these are in areas of Japan that were not subjected to the strategic bombing of World War II, such as in Shikoku or in the Japanese Alps. Great care is taken with these structures; open flame and smoking near the castles is usually prohibited, and visitors are usually required to remove their shoes before stepping on the wooden floors (slippers are usually provided). Local legends or ghost stories may also be associated with some of these castles; the most famous is probably the tale of Okiku and the Nine Plates, based on events that occurred at Himeji Castle.

At the other end of the spectrum are castles that have been left in ruins, though usually after archaeological surveys and excavations have been done.[22] Most of these belong to or are maintained by local municipal governments. Some have been incorporated into public parks, such as the ruins of Kuwana Castle and Matsuzaka Castle in Mie Prefecture, Kunohe Castle (Ninohe, Iwate Prefecture), or Sunpu Castle (Shizuoka City). Others have been left in more natural state, often with a marked hiking trail, such as Azaka Castle, (Matsuzaka, Mie Prefecture), Kame Castle (Inawashiro, Fukushima Prefecture), Kikoe Castle (Kagoshima city), or Kanegasaki Castle (Tsuruga city, Fukui Prefecture). The grounds of some were developed with municipal buildings or schools. In Toba, Mie Prefecture, the city hall and an elementary school were built on the site of Toba Castle.

Some castle sites are now in the hands of private landowners, and the area has been developed. Vegetable plots now occupy the site of Kaminogo Castle (Gamagōri, Aichi), and a chestnut orchard has been planted on the site of Nishikawa Castle, though in both cases some of the castle-related topography can still be seen, such as the motte or ramparts.

Finally there are the castle sites that have not been maintained or developed to any degree, and may have few markings or signs. Historical significance and local interest are too low to warrant additional costs. This includes Nagasawa Castle (Toyokawa, Aichi), Sakyoden Castle (Toyohashi, Aichi), Taka Castle (Matsuzaka, Mie), and Kuniyoshi Castle (Mihama, Fukui Prefecture). Castle sites of this type also include nearly every area marked "Castle Mountain" (城山 Shiroyama) on the maps of towns and cities across Japan. Because the castle was small or may have been used for a short time in centuries past, the name of the castle is often lost to history, such as the "Shiroyama" at Sekigahara, Gifu Prefecture, or the "Shiroyama" between Lake Shōji and Lake Motosu near Mount Fuji, Yamanashi Prefecture. In such cases, locals might not be aware there ever was a castle, believing that the name of the mountain is "just a name". Detailed city maps will often have such sites marked. At the site, castle-related landscaping, such as ramparts, partly filled wells, and a leveled hilltop or a series of terraces, will provide evidence of the original layout of the castle.

Whether their buildings are historical or reconstructions or a mix of the two, numerous castles across Japan serve as history and folk museums, as points of pride for local people, and as tangible structures reflecting Japanese history and heritage.[22] As castles are associated with the martial valor of past warriors, there are often monuments near castle structures or in their parks dedicated to either samurai or soldiers of the Imperial Army who died in war, such as the monument to the 18th Infantry Regiment near the ruins of Yoshida Castle (Toyohashi, Aichi). Castle grounds are often developed into parks for the benefit of the public, and planted with cherry blossom trees, plum blossom trees, and other flowering plants. Hirosaki Castle in Aomori Prefecture and Matsumae Castle in Hokkaido are both famous in their respective regions for their cherry blossom trees. The efforts of dedicated groups, as well as various agencies of the government has been to keep castles as relevant and visible in the lives of the Japanese people, to showcase them to visitors, and thus prevent the neglect of national heritage.[23]

Architecture and defenses

[edit]Japanese castles were built in a variety of environments, but all were constructed within variations of a fairly well-defined architectural scheme. Yamajiro (山城), or "mountain castles", were the most common, and provided the best natural defenses. However, castles built on flat plains (平城, hirajiro) and those built on lowlands hills (平山城, hirayamajiro) were not uncommon, and a few very isolated castles were even built on small natural or artificial islands in lakes or the sea, or along the shore. The science of building and fortifying castles was known as chikujō-jutsu (Japanese: 築城術).[24][25]

Walls and foundations

[edit]

Japanese castles were almost always built atop a hill or mound, and often an artificial mound would be created for this purpose (similar to European motte-and-bailey castles). This not only aided greatly in the defense of the castle, but also allowed it a greater view over the surrounding land, and made the castle look more impressive and intimidating. In some ways, the use of stone, and the development of the architectural style of the castle, was a natural step up from the wooden stockades of earlier centuries. The hills gave Japanese castles sloping walls, which many argue helped (incidentally) to defend them from Japan's frequent earthquakes. There is some disagreement among scholars as to whether or not these stone bases were easy to scale; some argue that the stones made easy hand- and footholds,[5] while others retort that the bases were steep, and individual stones could be as large as 6 m (20 ft) high, making them difficult if not next to impossible to scale.[6] The stone walls of Japanese castles were built under the leadership of the stonemasonry group called the Anōshū.[26]

Thus, a number of measures were invented to keep attackers off the walls and to stop them from climbing the castle, including pots of hot sand, gun emplacements, and arrow slits from which defenders could fire at attackers while still enjoying nearly full cover. Spaces in the walls for firing from were called sama; arrow slits were called yasama, gun emplacements tepposama and the rarer, later spaces for cannon were known as taihosama.[27] Unlike in European castles, which had walkways built into the walls, in Japanese castles, the walls' timbers would be left sticking inwards, and planks would simply be placed over them to provide a surface for archers or gunners to stand on. This standing space was often called the ishi uchi tana or "stone throwing shelf". Other tactics to hinder attackers' approaches to the walls included caltrops, bamboo spikes planted into the ground at a diagonal, or the use of felled trees, their branches facing outwards and presenting an obstacle to an approaching army (abatis). Many castles also had trapdoors built into their towers, and some even suspended logs from ropes, to drop on attackers.

The Anō family from Ōmi Province were the foremost castle architects in the late 16th century, and were renowned for building the 45-degree stone bases, which began to be used for keeps, gatehouses, and corner towers, not just for the castle mound as a whole.

Japanese castles, like their European cousins, featured massive stone walls and large moats. However, walls were restricted to the castle compound itself; they were never extended around a jōkamachi (castle town), and only very rarely were built along borders. This comes from Japan's long history of not fearing invasion, and stands in stark contrast to philosophies of defensive architecture in Europe, China, and many other parts of the world.[Notes 4] Even within the walls, a very different architectural style and philosophy applied, as compared to the corresponding European examples. A number of tile-roofed buildings, constructed from plaster over skeletons of wooden beams, lay within the walls, and in later castles, some of these structures would be placed atop smaller stone-covered mounds. These wooden structures were surprisingly fireproof, as a result of the plaster used on the walls. Sometimes a small portion of a building would be constructed of stone, providing a space to store and contain gunpowder.

Though the area inside the walls could be quite large, it did not encompass fields or peasants' homes, and the vast majority of commoners likewise lived outside the castle walls. Samurai lived almost exclusively within the compound, those of higher rank living closer to the daimyō's central keep. In some larger castles, such as Himeji, a secondary inner moat was constructed between this more central area of residences and the outer section where lower-ranking samurai kept their residences. Only a very few commoners, those directly in the employ and service of the daimyō or his retainers, lived within the walls, and they were often designated portions of the compound to live in, according to their occupation, for purposes of administrative efficiency. Overall, it can be said that castle compounds contained only those structures belonging to the daimyō and his retainers, and those important to the administration of the domain.

Layout

[edit]

The primary method of defense lay in the arrangement of the baileys, called maru (丸) or kuruwa (曲輪). Maru, meaning 'round' or 'circle' in most contexts, here refers to sections of the castle, separated by courtyards. Some castles were arranged in concentric circles, each maru lying within the last, while others lay their maru in a row; most used some combination of these two layouts. Since most Japanese castles were built atop a mountain or hill, the topography of the location determined the layout of the maru.

The "most central bailey", containing the keep, was called honmaru (本丸), and the second and third were called ni-no-maru (二の丸) and san-no-maru (三の丸) respectively. These areas contained the main tower and residence of the daimyō, the storerooms (kura 蔵 or 倉), and the living quarters of the garrison. Larger castles would have additional encircling sections, called soto-guruwa or sōguruwa.[Notes 5] At many castles still standing today in Japan, only the honmaru remains. Nijō Castle in Kyoto is an interesting exception, in that the ni-no-maru remains largely intact, while all that remains of the honmaruare the stone walls and foundations, along with one gatehouse.

The arrangement of gates and walls sees one of the key tactical differences in design between the Japanese castle and its European counterpart. A complex system of a great many gates and courtyards leading up to the central keep serves as one of the key defensive elements. This was, particularly in the case of larger or more important castles, very carefully arranged to impede an invading army and to allow fallen outer portions of the compound to be regained with relative ease by the garrisons of the inner portion. The defenses of Himeji castle are an excellent example of this. Since sieges rarely involved the wholesale destruction of walls, castle designers and defenders could anticipate the ways in which an invading army would move through the compound, from one gate to another. As an invading army passed through the outer rings of the Himeji compound, it would find itself directly under windows from which rocks, hot sand, or other things could be dropped,[28] and also in a position that made them easy shots for archers in the castle's towers. Gates were often placed at tight corners, forcing a bottleneck effect upon the invading force, or even simply at right angles within a square courtyard. Passageways would often lead to blind alleys, and the layout would often prevent visitors (or invaders) from being able to see ahead to where different passages might lead. All in all, these measures made it impossible to enter a castle and travel straight to the keep. Invading armies, as well as, presumably, anyone else entering the castle, would be forced to travel around and around the complex, more or less in a spiral, gradually approaching the center, all while the defenders prepared for battle, and rained down arrows and worse upon the attackers.[29]

All of that said however, castles were rarely forcibly invaded. It was considered more honorable, and more appropriate, for a defender's army to sally forth from the castle to confront his attackers. When this did not happen, sieges were most often performed not through the use of siege weapons or other methods of forced entry, but by surrounding the enemy castle and simply denying food, water, or other supplies to the fortress. As this tactic could often take months or even years to see results, the besieging army sometimes even built their own castle or fortress nearby. This being the case, "the castle was less a defensive fortress than a symbol of defensive capacity with which to impress or discourage the enemy". It of course also served as the lord's residence, a center of authority and governance, and in various ways a similar function to military barracks.

Buildings

[edit]

The castle keep, usually three to five stories tall, is known as the tenshukaku (天守閣) or tenshu (天守), and may be linked to a number of smaller buildings of two or three stories. Some castles, notably Azuchi, had keeps of as many as seven stories. The keep was the tallest and most elaborate building in the complex, and often also the largest. The number of stories and building layout as perceived from outside the keep rarely corresponds to the internal layout; for example, what appears to be the third story from outside may in fact be the fourth. This certainly must have helped to confuse attackers, preventing them from knowing which story or which window to attack, and likely disorienting the attacker somewhat once he made his way in through a window.

The least militarily equipped of the castle buildings, the keep was defended by the walls, gates and towers, and its ornamental role was never ignored; few buildings in Japan, least of all castle keeps, were ever built with attention to function purely over artistic and architectural form. Keeps were meant to be impressive not only in their size and in implying military might, but also in their beauty and the implication of a daimyō's wealth. Though castles owned by powerful daimyōs more often than not had main keeps, many lesser castles did not have them.[30] Though obviously well within the general sphere of Japanese architecture, much of the aesthetics and design of the castle was quite distinct from styles or influences seen in Shintō shrines, Buddhist temples, or Japanese homes. The intricate gables and windows are a fine example of this.

On those occasions when a castle was infiltrated or invaded by enemy forces, the central keep served as the last bastion of refuge, and a point from which counter-attacks and attempts to retake the castle could be made. If the castle ultimately fell, certain rooms within the keep would more often than not become the site of the seppuku (ritual suicide) of the daimyō, his family, and closest retainers.

Arguably the most important structures at Japanese castles were the castle palaces, known as 'goten.' These were the main buildings that served as the base and residence of the feudal lords, as well as the castles' administrative centers.[31] Few complete goten survive at Japanese castles today, though a number of individual goten buildings still exist, and some have also been reconstructed. They tended to be wide, low buildings with luxurious interiors.

Palisades lined the top of the castle's walls, and patches of trees, usually pines, symbolic of eternity or immortality, were planted along them. These served the dual purpose of adding natural beautiful scenery to a daimyō's home, representing part of his garden, and also obscuring the insides of the castle compound from spies or scouts.

A variety of towers or turrets, called yagura (櫓), placed at the corners of the walls, over the gates, or in other positions, served a number of purposes. Though some were used for the obvious defensive purposes, and as watchtowers, others served as water towers or for moon-viewing. As the residences of purportedly wealthy and powerful lords, towers for moon-viewing, balconies for taking in the scenery, tea rooms and gardens proliferated. These were by no means solely martial structures, but many elements served dual purposes. Gardens and orchards, for example, though primarily simply for the purpose of adding beauty and a degree of luxuriousness to the lord's residence, could also provide water and fruit in case of supplies running down due to siege, as well as wood for a variety of purposes.

Japanese castles also contained a variety of gates, some of them simple, and others quite elaborate. Many of them were yaguramon, literally 'turret gates': large gatehouses with a turret running along the top of the gate. Other gates were simpler. Japanese castles have many examples of 'masugata' gate complexes, which usually consisted of two gates placed at right angles and joined by walls to create a square enclosure which would trap would-be invaders, who then could be attacked from the turret gates or walls.[30]

Gallery

[edit]Aerial views of Japanese castles reveal a consistent military strategy that informs the over-all planning for each unique location.

-

Aerial view of Edo Castle—today the location of Tokyo Imperial Palace

-

Aerial view of Sunpu Castle

-

Aerial view of Nagoya Castle

-

Aerial view of Fukuoka Castle

-

Aerial view of Hirosaki Castle

-

Aerial view of Hirado Castle

-

Aerial view of Takamatsu Castle (Sanuki), with superimposed lines representing the original castle

See also

[edit]- 100 Fine Castles of Japan

- Continued 100 Fine Castles of Japan

- Castle

- Chashi—fortifications built by Ainu people

- Gusuku—the castles of the Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Jin'ya

- List of foreign-style castles in Japan

- Korean-style fortresses in Japan

- List of castles in Japan

- List of National Treasures of Japan (castles)

- Nightingale floor

Notes

[edit]- ^ The term samurai, deriving from saburai ("one who serves"), refers both to the armed feudal retainers who fought for their lords in feudal Japan, but also to the noble warrior class as a whole. Thus, unlike the European knight, the samurai was a samurai by virtue of his birth, retaining this status regardless of his rank. The samurai bore close ties to his clan (the noble family of his lineage), and to other clans to which his own owed fealty, serving loyally in the defence of his lord's lands, in attacks of enemy lands, or in a great number of other ways. For more on the role of the samurai class and its development over time, see samurai.

- ^ The only invasion attempts upon Japan in the 2nd millennium, these had a not insignificant impact upon defences in and around Hakata, where the Mongols landed, but are exceptions to the trend of internal warfare which guided military developments in pre-modern Japan.

- ^ Satsuma Domain in Kyūshū, one of the wealthiest and most powerful domains, doled out sub-fiefs and was allowed by the shogunate to maintain a number of subsidiary castles within their domain; this came largely out of Satsuma's strength and leadership, as well as the inability of the shogunate to effectively enforce many policies in Satsuma.

- ^ Consider, for example, defenses such as Hadrian's Wall and the Great Wall of China, as well as the city walls built throughout Europe and England across history, by the Romans and for centuries afterwards, as well as Chinese city walls and other examples elsewhere.

- ^ While maru (丸) most literally translates simply to "round" or "circle", kuruwa denotes an area enclosed by earthworks or other walls, and was a term also used to denote the enclosed red-light districts such as the Yoshiwara during the Edo period. As it relates to castles, most castles had three maru, main baileys, which could be called kuruwa; additional areas beyond this would be called sotoguruwa (外廓), or "kuruwa that are outside".

References

[edit]- ^ Inoue, Munekazu (1959). Castles of Japan. Tokyo: Association of Japanese Castle.

- ^ DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Japan. London: DK Publishing. 2002.

- ^ a b Treat, Robert; Alexander Soper (1955). The Art and Architecture of Japan. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ 天守閣は物置だった?「日本の城」の教養10選 (in Japanese). Toyo Keizai. 23 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Japanese Castles 1540–1640. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- ^ a b Hirai, Kiyoshi (1973). Feudal Architecture of Japan. Tokyo: Heibonsha.

- ^ Sansom (1961), pp.223–227.

- ^ Brown, Delmer (1948). "The Impact of Firearms on Japanese Warfare, 1543–1598". Far Eastern Quarterly. 7 (3): 236–253. doi:10.2307/2048846. JSTOR 2048846. S2CID 162924328.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & Co.

- ^ Nijōjō ninomaru teien 二条城二之丸庭園

- ^ Journal of Asian Studies 16:3 (May 1957), p366–367.

- ^ Clements (2010), p.293.

- ^ Clements (2010), p.294.

- ^ Drea (2009), pp.15–17.

- ^ Clements (2010), pp.295–296.

- ^ a b Nishi, Kazuo; Hozumi, Kazuo (1996) [1983]. What is Japanese architecture? (illustrated ed.). Kodansha International. p. 93. ISBN 4-7700-1992-0.

- ^ Alexander, Joseph H. (1996). "Assault on Shuri". The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa. Marine Corps History and Museums Division. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Electrical fault could have caused inferno at Okinawa's Shuri Castle, police say". The Japan Times Online. 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019.

- ^ Enders and Gutschow (1998), pp.12–13.

- ^ Robertson (2005), p.39.

- ^ McVeigh (2004), pp.47, 157.

- ^ a b Clements (2010), p.312.

- ^ Clements (2010), p.313.

- ^ Durbin, W; The Fighting Arts of the Samurai, article in Black Belt Magazine, March 1990 Vol. 28, No. 3

- ^ Draeger, Donn F. & Smith, Robert W.; Comprehensive Asian fighting arts Kodansha International, 1980, p84

- ^ Anoshuzumi Stone Walls (Japan Travel by Navitime)

- ^ Ratti, Oscar and Adele Westbrook (1973). Secrets of the Samurai. Edison, NJ: Castle Books.

- ^ Elison (1991), p.364.

- ^ Nakayama (2007), p.60–3.

- ^ a b "Features".

- ^ https://saga-museum.jp/sagajou/navi/en/53.html

Bibliography

[edit]- Benesch, Oleg. "Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 28 (Dec. 2018), pp. 107–134.

- Benesch, Oleg and Ran Zwigenberg (2019). Japan's Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 9781108481946.

- Clements, Jonathan (2010). A Brief History of the Samurai: A New History of the Warrior Elite. London: Constable and Robinson.

- De Lange, William (2021). An Encyclopedia of Japanese Castles. Groningen: Toyo Press. pp. 600 pages. ISBN 978-9492722300.

- Drea, Edward J. (2009). Japan's Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853–1945. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas.

- Elison, G. (1991). Deus Destroyed: The Image of Christianity in Early Modern Japan. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Enders, Siegfried R. C. T.; Gutschow, Niels (1998). Hozon: architectural and urban conservation in Japan. London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 3-930698-98-6.

- McVeigh, Brian J. (2004). Nationalisms of Japan: managing and mystifying identity. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-2455-8.

- Nakayama, Yoshiaki (2007). もう一度学びたい日本の城 [Let's learn again about Japanese Castles] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Seitosha. ISBN 978-4-7916-1421-9.

- Robertson, Jennifer Ellen (2005). A Companion to the Anthropology of Japan. Blackwell Companions to Social and Cultural Anthropology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22955-8.

- Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan: 1334-1615. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002). War in Japan 1467–1615. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Further reading

[edit]- Cluzel, Jean-Sébastien (2008). Architecture éternelle du Japon – De l'histoire aux mythes. Dijon: Editions Faton. ISBN 978-2-87844-107-9.

- De Lange, William (2021). An Encyclopedia of Japanese Castles. Groningen: Toyo Press. pp. 600 pages. ISBN 978-9492722300.

- Schmorleitz, Morton S. (1974). Castles in Japan. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 0-8048-1102-4.

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

- Mitchelhill, Jennifer (2013). Castles of the Samurai: Power & Beauty. US: Kodansha. ISBN 978-1568365121.

External links

[edit]- Guide of Japanese Castles

- Japanese Castle Explorer

- 130+ Japanese Castles Archived 2017-03-02 at the Wayback Machine GoJapanGo.com

- Castles of Japan

- Japan Top 100 Castles and castle ruins Archived 2016-09-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Photos of Japanese Castles Archived 2013-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

- The Japan's Modern Castles YouTube channel, featuring virtual tours of castle sites and discussing their modern history

Japanese castle

View on GrokipediaThe architectural emphasis on layered defenses—combining moats, earthen ramparts, and interlocking stone bases—reflected causal priorities of deterrence through visibility and inaccessibility, rather than sheer mass like European counterparts, enabling rapid assembly by mobilized labor but vulnerability to fire, which destroyed many during sieges or later neglect.[4] Beyond fortification, castles functioned as urban nuclei (jōkamachi), housing samurai retainers and fostering economic control, with opulent interiors blending defensive slits for archery and musketry alongside shoin-style reception halls for diplomacy.[7] Their legacy endures in preserved national treasures and reconstructions, underscoring Japan's feudal hierarchy, though post-war concrete replicas at sites like Osaka highlight tensions between historical authenticity and tourism-driven preservation.[8]