Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mary Rogers

View on WikipediaMary Cecilia Rogers (born c. 1820 – found dead July 28, 1841) was an American murder victim whose story became a national sensation.

Key Information

Rogers was a noted beauty who worked in a New York tobacco store, which attracted the custom of many distinguished men. When her body was found in the Hudson River, she was assumed to have been the victim of gang violence. However, one witness swore that she was dumped after a failed abortion attempt, and her boyfriend's suicide note suggested possible involvement on his part. Rogers' death remains unexplained. She inspired Edgar Allan Poe's pioneering detective story "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt".

Early life

[edit]Mary Rogers was probably born in 1821 in Lyme, Connecticut, though her birth records have not survived.[1] She was a beautiful young woman who grew up as the only child of her widowed mother. At the age of 20, Mary lived in the boarding house that was run by her mother.[2] Her father James Rogers died in a steamboat explosion when she was 17 years old, and she took a job as a clerk in a tobacco shop owned by John Anderson in New York City.[3]

Anderson paid her a generous wage in part because her physical attractiveness brought in many customers. One customer wrote that he spent an entire afternoon at the store only to exchange "teasing glances" with her. Another admirer published a poem in the New York Herald referring to her heaven-like smile and her star-like eyes.[1] Some of her customers included notable literary figures James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, and Fitz-Greene Halleck.[4]

First disappearance

[edit]On October 5, 1838, the newspaper the Sun reported that "Miss Mary Cecilia Rogers" had disappeared from her home.[3] Her mother Phoebe said she found a suicide note which the local coroner analyzed and said revealed a "fixed and unalterable determination to destroy herself".[1] The next day, however, the Times and Commercial Intelligence reported that the disappearance was a hoax and that Rogers only went to visit a friend in Brooklyn.[3] The New York Sun had previously published a story known as the Great Moon Hoax in 1835, causing controversy.[5] Some suggested this return was actually the hoax, evidenced by Rogers' failure to return to work immediately. When she finally resumed working at the tobacco shop, one newspaper suggested the whole event was a publicity stunt managed by Anderson.[1]

Murder

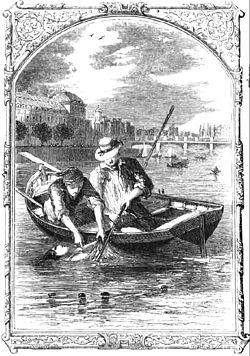

[edit]On July 25, 1841, Rogers told her fiancé Daniel Payne that she would be visiting her aunt and other family members.[3] Three days later, on July 28, the police found her corpse floating in the Hudson River in Hoboken, New Jersey.[6] Referred to as the "Beautiful Cigar Girl", the mystery of her death was sensationalized by newspapers and received national attention. The details of the case suggested she was murdered, or dumped by abortionist Madame Restell after a failed procedure.[7] Months later, the inquest still ongoing, her grief-stricken fiancé Daniel Payne committed suicide by overdosing on laudanum during a bout of heavy drinking. A remorseful note was found among the papers on his person where he died near Sybil's Cave on October 7, 1841, reading: "To the World – here I am on the very spot. May God forgive me for my misspent life."[8]

The story, much publicized by the press, also emphasized the ineptitude and corruption of the city's watchmen system of law enforcement.[9] At the time, New York City's population of 320,000 was served by an archaic force, consisting of one night watch, 100 city marshals, 31 constables, and 51 police officers.[10]

The popular theory was that Rogers was a victim of gang violence.[11] In November 1842, Frederica Loss came forward and swore that Rogers' death was the result of a failed abortion attempt. Police refused to believe her story, and the case remained unsolved.[3] Interest in the story waned nine weeks later when the press began publicizing a different, unrelated murder case,[12] that of John C. Colt's murder of Samuel Adams.[13]

In fiction

[edit]

Rogers' story was fictionalized most notably by Edgar Allan Poe as "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" (1842). The action of the story was relocated to Paris and the victim's body found in the River Seine.[11] Poe presented the story as a sequel to "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841), commonly considered the first modern detective story, and included its main character C. Auguste Dupin. As Poe wrote in a letter: "under the pretense of showing how Dupin... unravelled the mystery of Marie's assassination, I, in fact, enter into a very rigorous analysis of the real tragedy in New York."[14] In the story, Dupin suggests several possible solutions but never actually names the murderer.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Stashower, Daniel (2006). The Beautiful Cigar Girl. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 20–23. ISBN 0-525-94981-X.

- ^ vitelli, Romeo (2011). The Beautiful Cigar Girl. Toronto. ISBN 978-0-525-94981-7. Archived from the original on 2015-06-20. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z (Paperback ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 212–213. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- ^ McNamara, Joseph (2000). The Justice Story: True Tales of Murder, Mystery, Mayhem. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 99. ISBN 1-58261-285-4.

- ^ Willis, Jim (2010). 100 Media Moments that Changed America. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-313-35517-2.

- ^ Thomas, Dwight; Jackson, David K. (1987). The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1809–1849. New York: G. K. Hall & Co. pp. 336–337. ISBN 0-7838-1401-1.

- ^ Collins, Paul (2011). The Murder of the Century. Random House. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-307-59220-0.

- ^ Douglass MacGowan. "The Murder Mystery of Mary Rogers". www.trutv.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008.

- ^ Lardner, James; Reppetto, Thomas (2000). NYPD: A City and Its Police. Owl Books. pp. 18–21. ISBN 0-8050-6737-X.

- ^ Lankevich, George L. (1998). American Metropolis: A History of New York City. NYU Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-8147-5186-5.

- ^ a b Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 205. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- ^ Nelson, Randy F. (1981). The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc. p. 183. ISBN 0-86576-008-X.

- ^ Walsh, John (1968). Poe the Detective: the Curious Circumstances Behind The Mystery of Marie Roget. Rutgers University Press. p. 2.

"The Oblong Box" (not a story of crime as Poe told it) is based in part on the murder of the printer, Samuel Adams by John C. Colt, which succeeded the death of Mary Rogers as the leading sensational topic for the American press.

- ^ Rosenheim, Shawn James (1997). The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7.