Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

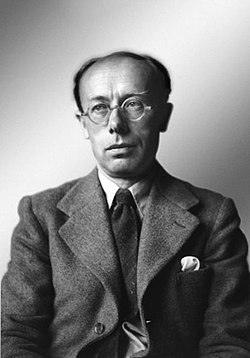

Max Newman

View on Wikipedia

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS[1] (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus,[6] the world's first operational, programmable electronic computer, and he established the Royal Society Computing Machine Laboratory at the University of Manchester, which produced the world's first working, stored-program electronic computer in 1948, the Manchester Baby.[7][8][9][10][11]

Key Information

Early life and education

[edit]Newman was born Maxwell Herman Alexander Neumann in Chelsea, London, England, to a Jewish family, on 7 February 1897.[4] His father was Herman Alexander Neumann, originally from the German city of Bromberg (now in Poland), who had emigrated with his family to London at the age of 15.[12] Herman worked as a secretary in a company, and married Sarah Ann Pike, an Irish schoolteacher, in 1896.[1]

The family moved to Dulwich in 1903, and Newman attended Goodrich Road school, then City of London School from 1908.[1][13] At school, he excelled in classics and in mathematics. He played chess and the piano well.[14]

Newman won a scholarship to study mathematics at St John's College, Cambridge in 1915, and in 1916 gained a First in Part I of the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos.[4]

World War I

[edit]Newman's studies were interrupted by World War I. His father was interned as an enemy alien after the start of the war in 1914, and upon his release he returned to Germany. In 1916, Herman changed his name by deed poll to the anglicised "Newman" and Sarah did likewise in 1920.[15] In January 1917, Newman took up a teaching post at Archbishop Holgate's Grammar School in York, leaving in April 1918. He spent some months in the Royal Army Pay Corps, and then taught at Chigwell School for six months in 1919 before returning to Cambridge.[12] He was called up for military service in February 1918, but claimed conscientious objection due to his beliefs and his father's country of origin, and thereby avoided any direct role in the fighting.[16]

Between the wars

[edit]Graduation

[edit]Newman resumed his interrupted studies in October 1919, and graduated in 1921 as a Wrangler (equivalent to a First) in Part II of the Mathematical Tripos, and gained distinction in Schedule B (the equivalent of Part III).[4][12] His dissertation considered the use of "symbolic machines" in physics, foreshadowing his later interest in computing machines.[14]

Early academic career

[edit]On 5 November 1923, Newman was elected a Fellow of St John's.[1] He worked on the foundations of combinatorial topology, and proposed that a notion of equivalence be defined using only three elementary "moves".[4] Newman's definition avoided difficulties that had arisen from previous definitions of the concept.[4] Publishing over twenty papers established his reputation as an "expert in modern topology".[14] Newman wrote Elements of the topology of plane sets of points,[5] a work on general topology and undergraduate text.[17] He also published papers on mathematical logic, and solved a special case of Hilbert's fifth problem.[1]

He was appointed a lecturer in mathematics at Cambridge in 1927.[4] His 1935 lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics and Gödel's theorem inspired Alan Turing to embark on his work on the Entscheidungsproblem (decision problem) that had been posed by Hilbert and Ackermann in 1928.[18] Turing's solution involved proposing a hypothetical programmable computing machine.[19] In spring 1936, Newman was presented by Turing with a draft of "On Computable Numbers with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". He realised the paper's importance and helped ensure swift publication.[14] Newman subsequently arranged for Turing to visit Princeton where Alonzo Church was working on the same problem but using his Lambda calculus.[12] During this period, Newman started to share Turing's dream of building a stored-program computing machine.[20]

During this time at Cambridge, he developed close friendships with Patrick Blackett, Henry Whitehead and Lionel Penrose.[14]

In September 1937, Newman and his family accepted an invitation to work for six months at Princeton. At Princeton, he worked on the Poincaré Conjecture and, in his final weeks there, presented a proof. However, in July 1938, after he returned to Cambridge, Newman discovered that his proof was fatally flawed.[14]

In 1939, Newman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[14]

Family life

[edit]In December 1934, he married Lyn Lloyd Irvine, a writer, with Patrick Blackett as best man.[1] They had two sons, Edward (born 1935) and William (born 1939).[12]

World War II

[edit]The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939. Newman's father was Jewish, which was of particular concern in the face of Nazi Germany, and Lyn, Edward and William were evacuated to America in July 1940, where they spent three years before returning to England in October 1943. After Oswald Veblen — maintaining 'that every able-bodied man ought to be carrying a gun or hand-grenade and fight for his country'— opposed moves to bring him to Princeton, Newman remained at Cambridge and at first continued research and lecturing.[12]

Government Code and Cypher School

[edit]By spring 1942, Newman was considering involvement in war work. He made enquiries. After Patrick Blackett recommended him to the Director of Naval Intelligence, Newman was sounded out by Frank Adcock in connection with the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park.[12]

Newman was cautious, concerned to ensure that the work would be sufficiently interesting and useful, and there was also the possibility that his father's German nationality would rule out any involvement in top-secret work.[21] The potential issues were resolved by the summer, and he agreed to arrive at Bletchley Park on 31 August 1942. Newman was invited by F. L. (Peter) Lucas to work on Enigma but decided to join Tiltman's group working on Tunny.[12]

Tunny

[edit]Newman was assigned to the Research Section and set to work on a German teleprinter cipher known as "Tunny". He joined the "Testery" in October.[22] Newman enjoyed the company[14] but disliked the work and found that it was not suited to his talents.[4] He persuaded his superiors that Tutte's method could be mechanised, and he was assigned to develop a suitable machine in December 1942. Shortly afterwards, Edward Travis (then operational head of Bletchley Park) asked Newman to lead research into mechanised codebreaking.[12]

The Newmanry

[edit]When the war ended, Newman was presented with a silver tankard inscribed 'To MHAN from the Newmanry, 1943–45'.[14]

Heath Robinson

[edit]Construction started in January 1943, and the first prototype was delivered in June 1943.[23] It was operated in Newman's new section, termed the "Newmanry", was housed initially in Hut 11 and initially staffed by himself, Donald Michie, two engineers, and 16 Wrens.[24] The Wrens nicknamed the machine the "Heath Robinson", after the cartoonist of the same name who drew humorous drawings of absurd mechanical devices.[24]

Colossus

[edit]The Robinson machines were limited in speed and reliability. Tommy Flowers of the Post Office Research Station, Dollis Hill had experience of thermionic valves and built an electronic machine, the Colossus computer which was installed in the Newmanry. This was a great success and ten were in use by the end of the war.

Later academic career

[edit]Fielden Chair, Victoria University of Manchester

[edit]In September 1945, Newman was appointed head of the Mathematics Department and to the Fielden Chair of Pure Mathematics at the University of Manchester.[20][25]

Computing Machine Laboratory

[edit]I am ... hoping to embark on a computing machine section here, having got very interested in electronic devices of this kind during the last two or three years ... I am of course in close touch with Turing.

— Newman, letter to von Neumann, 1946[20]

Newman lost no time in establishing the renowned Royal Society Computing Machine Laboratory at the university.[25] In February 1946, he wrote to John von Neumann, expressing his desire to build a computing machine.[20] The Royal Society approved Newman's grant application in July 1946.[20] Frederic Calland Williams and Thomas Kilburn, experts in electronic circuit design, were recruited from the Telecommunications Research Establishment.[20][25] Kilburn and Williams built Baby, the world's first electronic stored-program digital computer based on Alan Turing's and John von Neumann's ideas.[20][25]

Now let's be clear before we go any further that neither Tom Kilburn nor I knew the first thing about computers when we arrived at Manchester University... Newman explained the whole business of how a computer works to us.

— Frederic Calland Williams, co-creator of Manchester Baby[20]

After the Automatic Computing Engine suffered delays and set backs, Turing accepted Newman's offer and joined the Computer Machine Laboratory in May 1948 as Deputy Director (there being no Director). Turing joined Kilburn and Williams to work on Baby's successor, the Manchester Mark I. Collaboration between the University and Ferranti later produced the Ferranti Mark I, the first mass-produced computer to go on sale.[20]

Retirement

[edit]Newman retired in 1964 to live in Comberton, near Cambridge. After Lyn's death in 1973, he married Margaret Penrose, widow of his friend Lionel Penrose, father of Sir Roger Penrose.[14][26]

He continued to do research on combinatorial topology during a period when England was a major centre of activity notably Cambridge under the leadership of Christopher Zeeman. Newman made important contributions leading to an invitation to present his work at the 1962 International Congress of Mathematicians in Stockholm at the age of 65, and proved a Generalized Poincaré conjecture for topological manifolds in 1966.

At the age of 85, Newman began to suffer from Alzheimer's disease. He died in Cambridge in 1984, two years later.[14]

Honours

[edit]- Fellow of the Royal Society, elected 1939

- He was elected to membership of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society on 1 January 1945 [27]

- Royal Society Sylvester Medal, awarded 1958

- London Mathematical Society, President 1949–1951

- LMS De Morgan Medal, awarded 1962

- D.Sc. University of Hull, awarded 1968

The Newman Building at Manchester was named in his honour. The building housed the pure mathematicians from the Victoria University of Manchester between moving out of the Mathematics Tower in 2004 and July 2007 when the School of Mathematics moved into its new Alan Turing Building, where a lecture room is named in his honour. He was elected to membership of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society on 1 January 1945

In 1946, Newman declined the offer of an OBE as he considered the offer derisory.[24] Alan Turing had been appointed an OBE six months earlier and Newman felt that it was inadequate recognition of Turing's contribution to winning the war, referring to it as the "ludicrous treatment of Turing".[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Adams, J. F. (1985). "Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman. 7 February 1897–22 February 1984". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 31: 436–452. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1985.0015. S2CID 62649711.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Max Newman", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Max Newman at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wylie, Shaun (2004). "Newman, Maxwell Herman Alexander (1897–1984)". In Good, I. J (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31494. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Newman, Max (1939). Elements of the topology of plane sets of points. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24956-3.

- ^ Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press, USA. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Jack Copeland. "The Modern History of Computing". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ The Papers of Max Newman, St John's College Library

- ^ The Newman Digital Archive, St John's College Library & The University of Portsmouth

- ^ Anderson, David (2013). "Max Newman: Forgotten Man of Early British Computing". Communications of the ACM. 56 (5): 29–31. doi:10.1145/2447976.2447986. S2CID 1904488.

- ^ Max Newman publications indexed by Microsoft Academic

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j William Newman, "Max Newman – Mathematician, Codebreaker and Computer Pioneer", pp. 176–188 in Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press, USA. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Heard, Terry (2010). "Max Newman's Medal". John Carpenter Club (City of London School Alumni). Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

the [John Carpenter Club] archive has recently acquired the Beaufoy Medal for Mathematics awarded to Max Newman in 1915

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Newman, William (2010). "14. Max Newman - Mathematician, Codebreaker, and Computer Pioneer". In Copeland, B. Jack (ed.). Colossus The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers. Oxford University Press. pp. 176–188. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Anderson, D. (2007). "Max Newman: Topologist, Codebreaker, and Pioneer of Computing". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 29 (3): 76–81. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2007.4338447.

- ^ Paul Gannon, Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press, USA. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6. pp. 225–226.

- ^ Smith, P. A. (1939). "Review of Elements of the Topology of Plane Sets of Points by M. H. A. Newman" (PDF). Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 45 (11): 822–824. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1939-07087-0.

- ^ David Hilbert and Wilhlem Ackermann. Grundzüge der Theoretischen Logik. Springer, Berlin, Germany, 1928. English translation: David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann. Principles of Mathematical Logic. AMS Chelsea Publishing, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, 1950.

- ^ Turing, A. M. (1936). "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. 2. 42 (1) (published 1937): 230–265. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230. S2CID 73712.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Copeland, Jack (2010). "9. Colossus and the Rise of the Modern Computer". In Copeland, B. Jack (ed.). Colossus The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–100. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Gannon, 2006, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Gannon, 2006, p. 228.

- ^ Jack Copeland with Catherine Caughey, Dorothy Du Boisson, Eleanor Ireland, Ken Myers, and Norman Thurlow, "Mr Newman's Section", p. 157 of pp. 158–175 in Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ a b c Jack Copeland, "Machine against Machine", pp. 64–77 in B. Jack Copeland, ed., in Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ a b c d Turing, Alan Mathison; Copeland, B. Jack (2004). The essential Turing: seminal writings in computing, logic, philosophy ... Oxford University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-19-825080-7. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ Prasannan, R (7 October 2020). "Tackling Sir Roger Penrose". The Week. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Memoirs And Proceedings Of The Manchester Literary And Philosophical Society Vol-46-47 (1947)

External links

[edit]- Archival materials

- The Max Newman Digital Archive has digital copies of materials from the library of St. John's College, Cambridge.

Max Newman

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Childhood and Family Background

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman was born on 7 February 1897 in Chelsea, London, the only child of Herman Alexander Neumann, a German immigrant who had arrived in England as a teenager and worked as a company secretary, and Sarah Ann Pike, an Irish schoolteacher from a Protestant farming family.[1][3][4] The family, of Jewish heritage through the paternal line, was non-observant in religious practice, though cultural influences from the father's German-Jewish background persisted alongside an emphasis on education fostered by both parents' professional lives in teaching and administration. The family name was changed from Neumann to Newman in 1916, following the father's internment as an enemy alien during World War I.[4][1] In 1903, the family relocated to the London suburb of Dulwich, where Newman initially attended Goodrich Road School before transferring in 1908 to the City of London School, a prestigious institution known for its rigorous academic program.[5][6] At the City of London School, Newman demonstrated exceptional aptitude in both classics and mathematics, with his early encounters in the latter subject igniting a lifelong passion that would define his career; he also engaged in extracurricular activities such as chess, further honing his analytical skills.[6][1]Studies at Cambridge

Newman entered St John's College, Cambridge, in 1915 on a scholarship from the City of London School to study mathematics.[1] In his first year, he achieved a First Class in Part I of the Mathematical Tripos in 1916, demonstrating exceptional aptitude in the rigorous Cambridge examination system.[5] His studies were soon interrupted by World War I, during which he served as an army paymaster and schoolmaster from 1916 to 1919.[1] Resuming his education in October 1919, Newman completed Part II of the Mathematical Tripos in 1921, again earning a First Class and being named a Wrangler, a distinction for top performers.[5] He also received a distinction in Schedule B, an advanced component equivalent to what later became Part III of the Tripos.[5] During his time at Cambridge, Newman developed a strong interest in pure mathematics, particularly logic and set theory, influenced by his reading of Bertrand Russell's Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy as an undergraduate.[1] Newman graduated in 1921, having focused his studies on foundational aspects of pure mathematics.[1]Interwar Period

Graduation and Early Academic Positions

Following his graduation from the University of Cambridge in 1921 with a degree in mathematics, Max Newman undertook a probationary year at St John's College before being elected a Fellow there on 5 November 1923, a position he held until 1945. This election recognized his early promise in mathematical research and allowed him to establish himself as a promising academic within the Cambridge community.[1] In 1927, Newman was appointed a University Lecturer in Mathematics at Cambridge, a role that complemented his fellowship and involved teaching advanced topics in pure mathematics and mathematical logic to undergraduate and graduate students. His lectures emphasized rigorous foundational aspects, fostering a deep engagement with logical structures and their implications for mathematical proof.[7] Newman actively mentored students during this time, including notable early interactions with Alan Turing on key questions in mathematical foundations; Turing, then a graduate student, attended Newman's 1935 course on the Foundations of Mathematics, which explored Gödel's incompleteness theorems and Hilbert's Entscheidungsproblem, profoundly influencing Turing's subsequent work. These discussions highlighted the challenges of mechanizing mathematical reasoning and laid groundwork for explorations in computability.[8] Newman's interests in the late 1920s and 1930s included the Entscheidungsproblem—the question of whether there exists an algorithm to determine the truth of any mathematical statement—and related problems in logic, which he explored in his lectures and discussions, contributing to the conceptual foundations of computability theory. During these years, his broader interests in combinatorial topology also began to take shape, bridging his logical inquiries with geometric abstractions.[9][1]Contributions to Topology

During the interwar period, Max Newman established himself as a leading figure in British mathematics through his pioneering contributions to combinatorial topology. His early work focused on developing rigorous foundations for the subject, drawing inspiration from the combinatorial methods of L.E.J. Brouwer and J.W. Alexander. In a series of papers from 1926 to 1932, Newman redefined key concepts such as topological equivalence and simplicial complexes, providing tools that advanced the understanding of spatial structures without reliance on metric properties. For instance, his 1928 paper "Topological equivalence of complexes" introduced precise criteria for determining when two simplicial complexes are topologically identical, emphasizing invariance under elementary transformations.[1][10] This work laid essential groundwork for later developments in algebraic topology by clarifying the combinatorial underpinnings of continuous deformations.[11] Newman's 1931 paper "Intersection-complexes. I. Combinatory theory" further innovated by exploring the intersections of simplicial complexes, offering a framework for analyzing how topological spaces overlap and interact at a combinatorial level.[10] This approach influenced the study of homology groups and fixed-point theorems, with applications to problems in Euclidean spaces as detailed in his 1930 publications "Combinatory topology and Euclidean n-space" and "Combinatory Topology of Convex Regions."[1] In 1939, Newman synthesized these ideas in his influential textbook Elements of the Topology of Plane Sets of Points, which provided an accessible yet rigorous introduction to general topology through the lens of plane sets, covering topics like connectedness, compactness, and separation axioms.[12] The book became a foundational resource for students and researchers, emphasizing conceptual clarity over abstract generality and earning praise for its elegant proofs of classical results. Newman's interwar research also had lasting impacts on algebraic topology, particularly in knot theory and manifold classification. Additionally, Newman's methods influenced J.H.C. Whitehead's development of homotopy theory, as Whitehead adapted Newman's elementary moves for simplicial complexes in his own studies of manifolds.[11] These contributions extended into higher dimensions, with roots in his 1920s-1930s papers informing later proofs of topological invariants. Newman's interwar combinatorial techniques laid the groundwork for his later 1966 proof of the Poincaré conjecture in dimensions greater than four.[1]Marriage and Family

In 1934, Max Newman married Lyn Lloyd Irvine, a writer and literary journalist associated with the Bloomsbury Group.[1][7] The couple had two sons: Edward, born in 1935, who pursued a career in mathematics and contributed to early computing projects such as the Automatic Computing Engine pilot model; and William, born in 1939, who became a prominent computer scientist specializing in computer graphics and human-computer interaction.[1][13][14] The family resided at Cross Road Farm in Comberton, near Cambridge, where Newman balanced his academic commitments at the university with domestic life.[15][11] Lyn supported Newman's intellectual endeavors through her own writing and connections in literary circles, fostering a home environment enriched by shared cultural pursuits.[7] This family stability contributed to Newman's focus during the interwar period. The household emphasized interests in music, chess, and reading, with Newman himself being a gifted pianist and skilled chess player.[3][11]World War II Contributions

Recruitment to Bletchley Park

In 1942, Max Newman was recruited to the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park based on his renowned mathematical expertise, particularly in logic and topology, which positioned him to tackle complex cryptanalytic problems. The recruitment process was initiated by physicist Patrick Blackett, who recommended Newman to the Director of Naval Intelligence on 13 May 1942, praising him as "one of the most intelligent people I know" and highlighting his skills as a first-class pure mathematician, philosopher, chess player, and musician. Newman joined on 31 August 1942 and was initially assigned to the Testery, a research section under Major Ralph Tester within Major G. W. Morgan's group, where manual methods were employed to break high-priority German codes. Gordon Welchman, head of Hut 6 and a former student who had attended Newman's lectures at Cambridge, played a key role by tasking Newman in December 1942—alongside or in place of GC&CS director Edward Travis—with developing mechanized approaches to cryptanalysis.[16][17] Newman's recruitment addressed the formidable challenges posed by the Lorenz cipher, codenamed Tunny by the Allies, a sophisticated teleprinter encryption system (Schlüsselzusatz or SZ40/42) used by the German High Command for secure communications between Hitler and his generals, far more complex than the Enigma machine due to its 12-wheel structure and additive key-stream generation. Unlike Enigma's rotor-based substitution, Tunny employed a Vernam-like stream cipher with chi and psi wheels producing pseudorandom keystreams, compounded by motor wheels that periodically altered the psi settings, creating depth variations that thwarted standard frequency analysis. Newman applied his logical approach to statistical analysis of teleprinter codes, emphasizing probabilistic methods to detect non-random patterns in ciphertext, such as "rectangles" (differences between message starts) and "runs" of letter combinations like i+j, to infer wheel settings without relying on cribs from known plaintext. This built on the initial hand-breaking success by Bill Tutte in 1942 but scaled it through quantitative scoring of wheel patterns to handle the cipher's vast key space of approximately 10^23 possibilities.[17] Upon arrival, Newman underwent brief training in practical cryptanalysis to familiarize himself with GC&CS procedures and Tunny-specific techniques, drawing on his prewar logical work—which had influenced Alan Turing's computability theories—to adapt abstract mathematical reasoning to wartime signals intelligence. He quickly identified the limitations of manual hand-methods in the Testery, which were too slow and error-prone for the increasing volume of Tunny traffic, often requiring days per message despite teams of expert linguists and mathematicians. To address mechanization needs, Newman collaborated with Post Office engineer Tommy Flowers starting in early 1943, proposing electronic devices to automate tape reading, pattern correlation, and wheel-breaking, recognizing that vacuum-tube counters could perform billions of comparisons far faster than mechanical relays or punched-tape synchronizers. Flowers, skeptical of valve reliability but convinced by Newman's specifications, began prototyping solutions at Dollis Hill.[17] The inefficiencies of manual decoding, which bottlenecked intelligence production and risked missing critical strategic insights, prompted Newman to advocate for a dedicated machine-oriented section; with backing from Travis and Welchman, he was authorized to lead the formation of the Newmanry on 1 February 1943, initially comprising one cryptographer, two engineers, and 16 Women's Royal Naval Service (Wrens) operators, focused exclusively on automating Tunny cryptanalysis to complement the Testery's hand efforts. This shift enabled rapid scaling, with the Newmanry relocating to Block F by late 1943 to accommodate growing machinery and staff.[17][18]Leadership of the Newmanry

In February 1943, Max Newman established the Newmanry, a specialized section at Bletchley Park dedicated to the mechanized cryptanalysis of the German Tunny cipher, initially operating from a single room.[17] By mid-1943, the section became fully operational, focusing on statistical methods to break the chi wheels of the Lorenz SZ40/42 machines used in high-level communications.[17] The team expanded rapidly under Newman's direction, reaching approximately 325 staff by April 1945, including about 22 cryptographers, 28 engineers, and 273 Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS) operators who handled machine operations and calculations.[17] Notable members included Donald Michie, the first recruit and a young mathematician who contributed to statistical techniques, and I. J. (Jack) Good, an expert in probability who joined early and advanced the section's theoretical work.[17] Newman organized the Newmanry into a collaborative structure, with mathematicians developing theoretical approaches to codebreaking and engineers implementing practical solutions, often in partnership with teams from the General Post Office at Dollis Hill.[17] This division enabled efficient progress, starting with early devices like the Heath Robinson for tape-based processing.[17] The section's daily output grew substantially, breaking hundreds to thousands of characters per day in earlier phases and reaching up to 400,000 letters processed daily in the reperforation room by March 1945, supporting the decryption of critical Tunny traffic.[17] Newman made key strategic decisions on resource allocation, prioritizing high-value targets through coordination with the Fish Committee, which oversaw Tunny efforts from May 1944 to January 1945, and focusing efforts on messages with strong strategic implications as identified by intelligence analysts.[17] He integrated the Newmanry closely with Ralph Tester's Testery section, where the Newmanry supplied de-chi'd text after removing the chi encryption layer, allowing the Testery to apply hand methods for the remaining psi and motor wheels; this partnership was facilitated by shared personnel, joint registries established in January 1944, and regular exchanges of cribs and settings.[17] The Newmanry's breakthroughs under Newman's leadership provided vital intelligence from decrypted Tunny messages, contributing to Allied planning for the D-Day invasion in June 1944 by revealing German command intentions and supporting broader war decisions through timely insights into high-level Axis communications.[17]Development of Codebreaking Machines

Under Max Newman's direction in the Newmanry at Bletchley Park, the development of specialized codebreaking machines began with the Heath Robinson in 1943, an electromechanical device designed to automate the cryptanalysis of the German Lorenz cipher used in high-level communications.[19] The machine, named after the cartoonist known for intricate contraptions, featured two paper tape readers: one for the intercepted ciphertext and another for simulated chi-wheel patterns derived from the Lorenz machine's settings.[20] It performed Boolean XOR operations on 5-bit teleprinter signals using electronic valve circuits to detect patterns, processing data at speeds of up to 2,000 characters per second for shorter tapes but typically limited to 1,000 characters per second for longer ones due to mechanical constraints.[20] Constructed at the General Post Office's Dollis Hill research station by engineers Tommy Flowers and Frank Morrell, the prototype was delivered in June 1943 and demonstrated the feasibility of mechanized pattern matching, though synchronization between the tapes proved unreliable as they stretched or tore at high speeds.[6] These limitations—frequent tape replacements, maintenance demands, and inability to handle multiple wheel patterns efficiently—restricted its output to just a few runs per day, prompting Newman to seek a more robust electronic solution.[21] Newman's collaboration with Tommy Flowers, a telecommunications engineer at Dollis Hill, led to the design of Colossus, the world's first large-scale programmable electronic digital computer, operational by January 1944.[22] Flowers implemented Newman's specifications for electronic cryptanalysis, replacing mechanical synchronization with shift registers based on thyratron rings to generate wheel patterns internally and perform Boolean operations on the ciphertext at 5,000 characters per second—five times faster than Heath Robinson.[6] The Mark I Colossus used approximately 1,500 to 1,800 vacuum tubes (valves) for logic and memory functions, reading a single looped paper tape while electronically simulating the other via ring counters, enabling efficient delta and double-delta attacks on the Lorenz cipher without physical tape alignment issues.[22] Subsequent Mark II versions, introduced in June 1944, incorporated up to 2,500 valves and parallel processing for multiple chi-wheel combinations, further boosting speed to 25,000 characters per second in later iterations.[6] By the war's end in 1945, ten Colossus machines had been built and deployed, decrypting millions of characters from Tunny traffic and providing critical intelligence to the Allies.[22] The machines' designs emphasized reliability through Flowers' innovative use of hot-cathode thyratrons for stable switching, overcoming skepticism from Newman's team about all-electronic systems.[6] Postwar, to maintain secrecy amid Cold War concerns, eight of the ten Colossus machines were dismantled and their components destroyed or repurposed, with the remaining two used briefly for other cryptographic tasks before similar fate; all related documentation was burned.[22] The existence and details of both Heath Robinson and Colossus remained classified until declassification in the mid-1970s, when veteran accounts and partial records began to reveal their pivotal role in wartime codebreaking.[22]Postwar Academic Career

Appointment at Manchester

In 1945, Max Newman was appointed as the Fielden Professor of Pure Mathematics at the University of Manchester, succeeding Louis Mordell who had moved to the Sadleirian Chair at Cambridge.[1][19] He relocated to Manchester with his wife, Lyn, and their two sons, settling into academic life after the war.[1][19] Upon arrival, Newman focused on rebuilding the mathematics department, which had been disrupted by the war, aiming to establish it as a center of excellence comparable to the best in Britain.[1][19] He emphasized applied mathematics and mathematical logic in his vision for the department, recruiting talented staff such as David Rees and I.J. Good to strengthen these areas.[1][19] This postwar shift reflected broader trends in British mathematics toward practical applications informed by wartime experiences. In 1946, Newman declined an offer of the Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), in protest against the inadequacy of Alan Turing's OBE for his vital war work.[19] His interest in computing had been sparked by the codebreaking machines developed during the war, leading him to begin planning facilities for electronic computing at Manchester.[1][19] These plans included securing funding from the Royal Society and assembling a team to explore general-purpose digital computers.[19]Establishment of the Computing Machine Laboratory

Following his appointment as Professor of Pure Mathematics at the University of Manchester in 1945, Max Newman established the Royal Society Computing Machine Laboratory in 1946 to advance electronic computing for mathematical applications. The laboratory received a substantial grant from the Royal Society, approved in July 1946 and funded by the Treasury, providing £20,000 in capital expenditure and £3,000 annually for salaries. This funding enabled the creation of dedicated facilities, marking one of the first major investments in postwar British computing infrastructure.[2][23] Newman recruited key personnel to bridge mathematical theory and practical engineering, including Frederic C. Williams, appointed to the Chair of Electro-Technics in late 1946, and Tom Kilburn, his assistant seconded from the Telecommunications Research Establishment. This team shifted the laboratory's focus from abstract mathematical theory—rooted in Newman's prewar topology work—to the development of practical electronic systems, drawing briefly on design principles from the Colossus codebreaking machines Newman had overseen during World War II. By autumn 1947, they had successfully installed cathode-ray tube memory systems, adapting standard oscilloscope tubes for data storage to enable reliable electronic computation.[19][23][2] The laboratory's initial operations emphasized numerical analysis and simulations to solve complex mathematical problems, such as multilength integer arithmetic for prime number factorization. These projects demonstrated the potential of electronic computing for pure mathematics, with early successes in computational efficiency that outpaced manual methods. Newman also prioritized training, funding positions like Alan Turing's in 1948 and providing instruction in programming techniques to students and staff, fostering a new generation skilled in machine operation and software development.[2][23][24] To scale beyond academic use, the laboratory collaborated with Ferranti Ltd., supplying components and expertise that led to commercial prototypes by 1950, including adaptations for industrial applications in engineering and science. This partnership accelerated the transition from experimental setups to marketable systems, with Ferranti producing the first commercially available stored-program computer in early 1951.[2][23]Key Innovations in Early Computing

Under Max Newman's oversight as Fielden Professor of Pure Mathematics at the University of Manchester, the Royal Society funded the establishment of an electronic computing laboratory in 1946, leading to the construction of the Small-Scale Experimental Machine, known as the Manchester Baby. This prototype demonstrated the viability of the stored-program concept, with its first successful execution of a stored program occurring on 21 June 1948. The Baby used cathode-ray tube memory for both data and instructions, marking a pivotal shift from fixed-program machines to general-purpose electronic digital computers.[19][1] The initial program run on the Baby implemented an algorithm to determine the highest proper factor of (262,144) through successive division tests, a task related to prime factorization that confirmed the machine's reliability after 52 minutes of operation. Newman's leadership ensured the integration of mathematical principles into the hardware design, emphasizing logical foundations for programmability. This success validated the feasibility of electronic stored-program computing, drawing on Newman's wartime experience with codebreaking machines to prove that such systems could handle complex numerical computations efficiently.[25][1] Building on the Baby, Newman's team transitioned to the Manchester Mark I by 1949, expanding memory to support programs up to 1,000 lines, including significant applications like a search for Mersenne primes that ran error-free for nine hours in April 1949. This advancement highlighted the scalability of stored-program architecture for mathematical research. Newman's earlier mentorship of Alan Turing, including support for the 1936 paper "On Computable Numbers," influenced Turing's 1945 Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) design at the National Physical Laboratory, where Newman's advocacy underscored the practical engineering of universal computing machines.[19][1] Newman promoted computing as a rigorous mathematical discipline through academic lectures and oversight of research, framing it as an extension of logic and topology into practical machinery. His 1935 Cambridge lectures on the foundations of mathematics had already inspired Turing's theoretical work, and postwar talks at institutions like the University of Warwick in 1964 reinforced computing's role in advancing pure mathematics. These efforts positioned electronic computers as tools for solving undecidable problems and exploring algorithmic limits.[1][19]Later Years and Legacy

Retirement and Ongoing Research

Newman retired from the Fielden Chair of Pure Mathematics at the University of Manchester in 1964 at the age of 67, becoming professor emeritus thereafter.[7] He relocated to Comberton, a village near Cambridge, where he spent the remainder of his life, maintaining an active engagement with mathematics despite formal retirement.[1] During this period, he held several visiting professorships, including at the Australian National University in 1964–1965 and 1967, Rice University in 1965–1966, and later at the University of Warwick.[7] In his later years, Newman extended his longstanding work in combinatorial topology, focusing on manifolds and higher-dimensional problems. He delivered an invited address on "Geometric Topology" at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Stockholm in 1962, published in the proceedings, which laid groundwork for subsequent advancements.[10] This culminated in his 1966 paper "The Engulfing Theorem for Topological Manifolds," published in the Annals of Mathematics, which provided key proofs resolving the higher-dimensional Poincaré conjecture for topological manifolds of dimension greater than four.[26] These contributions reaffirmed his influence in the field during a time when topological methods were evolving significantly.[19] Newman occasionally taught courses at the University of Warwick, where he was renowned as an outstanding educator, and remained involved in academic mentorship, including supervision of PhD students exploring combinatorial topology topics.[1] His family provided steadfast support in these pursuits, with his second wife, Margaret Penrose—whom he married in 1973 following the death of his first wife, Lyn—sharing in his intellectual and social life.[19] Amid his scholarly activities, Newman intensified personal hobbies, achieving advanced proficiency as a pianist capable of performing complex works like Beethoven concertos and competing at a high level in chess.[1]Honours and Awards

Newman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1939, recognizing his significant contributions to topology.[1] In 1958, he received the Sylvester Medal from the Royal Society, awarded for his outstanding achievements in pure mathematics, particularly in the fields of topology and combinatorial analysis.[1][7] Newman's leadership roles within mathematical societies further highlighted his stature. He served as President of the London Mathematical Society from 1949 to 1951, and in 1962, the society honored him with the De Morgan Medal for his lifelong service and contributions to mathematics.[1][7] His wartime codebreaking efforts were indirectly acknowledged through subsequent recognitions in computing and applied mathematics, underscoring the broader impact of his technical innovations.[7] In recognition of his enduring influence, several institutions named programs or facilities after Newman. The University of Cambridge established the Max Newman Research Fellowship in the Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics.[27] The Newman Building at the University of Manchester was named in his honor. He also received honorary degrees, including a Doctor of Science (DSc) from the University of Hull in 1968, and an honorary fellowship from St John's College, Cambridge, in 1973.[7]Death and Enduring Influence

In the early 1980s, during his declining health, Max Newman's second wife, Margaret Penrose, whom he had married in 1973 following the death of his first wife Lyn Irvine, provided devoted care.[7] Newman died peacefully on 22 February 1984 in Comberton, near Cambridge, England.[1] Family members, including his sons Edward and William, and colleagues from his long career in mathematics and computing, offered heartfelt tributes at his funeral, remembering him as a gentle, brilliant thinker whose curiosity extended to botany and birdwatching even in retirement.[28] Newman's enduring influence stems from his mentorship of Alan Turing, whose seminal 1936 paper "On Computable Numbers" was shaped by Newman's guidance at Cambridge, laying foundational concepts for theoretical computer science.[1] His leadership in developing codebreaking machines like Colossus during World War II, declassified in 1975, revealed his critical role in advancing electronic computing and shortening the war, as partial government releases highlighted the Newmanry's contributions to breaking the Lorenz cipher.[29] Posthumously, Newman's work has received growing recognition for establishing key principles in digital computing foundations, such as stored-program architectures at Manchester University, and in combinatorial topology through his 1920s innovations in manifold equivalence.[1] Biographies, including accounts by his son William Newman in Jack Copeland's 2006 book Colossus, and documentaries like the 2022 British Computer Society film A Mathematical Machine: Max Newman and Early Computing at Manchester, 1946-1951, have illuminated his understated yet transformative impact on modern technology and pure mathematics.[30]References

- https://www.[youtube](/page/YouTube).com/watch?v=iPIdtO_CxiY