Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wayland (protocol)

View on Wikipedia

| Wayland | |

|---|---|

| |

Weston, the reference implementation of a Wayland server | |

| Original author | Kristian Høgsberg |

| Developer | freedesktop.org et al. |

| Initial release | 30 September 2008[1] |

| Stable release | |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Official: Linux Unofficial: NetBSD, FreeBSD, OpenBSD, DragonFly BSD[4] Compatibility layer: Haiku[5] |

| Type | |

| License | MIT License[6][7][8] |

| Website | wayland |

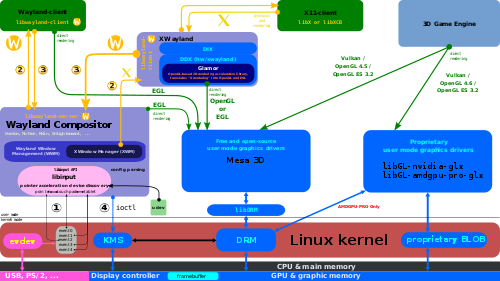

Wayland is a communication protocol that specifies the communication between a display server and its clients, as well as a C library implementation of that protocol.[9] A display server using the Wayland protocol is called a Wayland compositor, because it additionally performs the task of a compositing window manager.

Wayland is developed by a group of volunteers initially led by Kristian Høgsberg as a free and open-source community-driven project with the aim of replacing the X Window System with a secure[10][11][12][13] and simpler windowing system for Linux and other Unix-like operating systems.[9][14] The project's source code is published under the terms of the MIT License, a permissive free software license.[14][6] The Wayland project also develops an implementation of a Wayland compositor called Weston.[9]

Overview

[edit]

- The evdev module of the Linux kernel gets an event and sends it to the Wayland compositor.

- The Wayland compositor looks through its scenegraph to determine which window should receive the event. The scenegraph corresponds to what is on screen and the Wayland compositor understands the transformations that it may have applied to the elements in the scenegraph. Thus, the Wayland compositor can pick the right window and transform the screen coordinates to window local coordinates, by applying the inverse transformations. The types of transformation that can be applied to a window is only restricted to what the compositor can do, as long as it can compute the inverse transformation for the input events.

- As in the X case, when the client receives the event, it updates the UI in response. But in the Wayland case, the rendering happens by the client via EGL, and the client just sends a request to the compositor to indicate the region that was updated.

- The Wayland compositor collects damage requests from its clients and then re-composites the screen. The compositor can then directly issue an ioctl to schedule a pageflip with KMS.

The Wayland Display Server project was started by Red Hat developer Kristian Høgsberg in 2008.[15]

Beginning around 2010, Linux desktop graphics have moved from having "a pile of rendering interfaces... all talking to the X server, which is at the center of the universe" towards putting the Linux kernel and its components (i.e. Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI), Direct Rendering Manager (DRM)) "in the middle", with "window systems like X and Wayland ... off in the corner". This will be "a much-simplified graphics system offering more flexibility and better performance".[16]

Høgsberg could have added an extension to X as many recent projects have done, but preferred to "[push] X out of the hotpath between clients and the hardware" for reasons explained in the project's FAQ:[14]

What's different now is that a lot of infrastructure has moved from the X server into the kernel (memory management, command scheduling, mode setting) or libraries (cairo, pixman, freetype, fontconfig, pango, etc.), and there is very little left that has to happen in a central server process. ... [An X server has] a tremendous amount of functionality that you must support to claim to speak the X protocol, yet nobody will ever use this. ... This includes code tables, glyph rasterization and caching, XLFDs (seriously, XLFDs!), and the entire core rendering API that lets you draw stippled lines, polygons, wide arcs and many more state-of-the-1980s style graphics primitives. For many things we've been able to keep the X.org server modern by adding extension such as XRandR, XRender and COMPOSITE ... With Wayland we can move the X server and all its legacy technology to an optional code path. Getting to a point where the X server is a compatibility option instead of the core rendering system will take a while, but we'll never get there if [we] don't plan for it.

Wayland consists of a protocol and a reference implementation named Weston. The project is also developing versions of GTK and Qt that render to Wayland instead of to X. Most applications are expected to gain support for Wayland through one of these libraries without modification to the application.

Initial versions of Wayland have not provided network transparency, though Høgsberg noted in 2010 that network transparency is possible.[17] It was attempted as a Google Summer of Code project in 2011, but was not successful.[18] Adam Jackson has envisioned providing remote access to a Wayland application by either "pixel-scraping" (like VNC) or getting it to send a "rendering command stream" across the network (as in RDP, SPICE or X11).[19] As of early 2013, Høgsberg was experimenting with network transparency using a proxy Wayland server which sends compressed images to the real compositor.[20][21] In August 2017, GNOME saw the first such pixel-scraping VNC server implementation under Wayland.[22] In modern Wayland compositors, network transparency is handled in an xdg-desktop-portal implementation that implements the RemoteDesktop portal.

Many Wayland compositors also include an xdg-desktop-portal implementation for common tasks such as a native file picker for native applications and sandboxes such as Flatpak (xdg-desktop-portal-gtk is commonly used as a fallback filepicker), screen recording, network transparency, screenshots, color picking, and other tasks that could be seen as needing user intervention and being security risks otherwise. Note that xdg-desktop-portal is not Flatpak or Wayland-specific, and can be used with alternative packaging systems and windowing systems.

Software architecture

[edit]Protocol architecture

[edit]

The Wayland protocol follows a client–server model in which clients are the graphical applications requesting the display of pixel buffers on the screen, and the server (compositor) is the service provider controlling the display of these buffers.

The Wayland reference implementation has been designed as a two-layer protocol:[23]

- A low-level layer or wire protocol that handles the inter-process communication between the two involved processes—client and compositor—and the marshalling of the data that they interchange. This layer is message-based and usually implemented using the kernel IPC services, specifically Unix domain sockets in the case of Linux and other Unix-like operating systems.[24]

- A high-level layer built upon it, that handles the information that client and compositor need to exchange to implement the basic features of a window system. This layer is implemented as "an asynchronous object-oriented protocol".[25]

While the low-level layer was written manually in C, the high-level layer is automatically generated from a description of the elements of the protocol stored in XML format.[26] Every time the protocol description of this XML file changes, the C source code that implements such protocol can be regenerated to include the new changes, allowing a very flexible, extensible and error-proof protocol.

The reference implementation of Wayland protocol is split in two libraries: a library to be used by Wayland clients called libwayland-client and a library to be used by Wayland compositors called libwayland-server.[27]

Protocol overview

[edit]The Wayland protocol is described as an "asynchronous object-oriented protocol".[25] Object-oriented means that the services offered by the compositor are presented as a series of objects living on the same compositor. Each object implements an interface which has a name, a number of methods (called requests) as well as several associated events. Every request and event has zero or more arguments, each one with a name and a data type. The protocol is asynchronous in the sense that requests do not have to wait for synchronized replies or ACKs, avoiding round-trip delay time and achieving improved performance.

The Wayland clients can make a request (a method invocation) on some object if the object's interface supports that request. The client must also supply the required data for the arguments of such request. This is the way the clients request services from the compositor. The compositor in turn sends information back to the client by causing the object to emit events (probably with arguments too). These events can be emitted by the compositor as a response to a certain request, or asynchronously, subject to the occurrence of internal events (such as one from an input device) or state changes. The error conditions are also signaled as events by the compositor.[25]

For a client to be able to make a request to an object, it first needs to tell the server the ID number it will use to identify that object.[25] There are two types of objects in the compositor: global objects and non-global objects. Global objects are advertised by the compositor to the clients when they are created (and also when they are destroyed), while non-global objects are usually created by other objects that already exist as part of their functionality.[28]

The interfaces and their requests and events are the core elements that define the Wayland protocol. Each version of the protocol includes a set of interfaces, along with their requests and events, which are expected to be in any Wayland compositor. Optionally, a Wayland compositor may define and implement its own interfaces that support new requests and events, thereby extending functionality beyond the core protocol.[29] To facilitate changes to the protocol, each interface contains a "version number" attribute in addition to its name; this attribute allows for distinguishing variants of the same interface. Each Wayland compositor exposes not only what interfaces are available, but also the supported versions of those interfaces.[30]

Wayland core interfaces

[edit]The interfaces of the current version of Wayland protocol are defined in the file protocol/wayland.xml of the Wayland source code.[26] This is an XML file that lists the existing interfaces in the current version, along with their requests, events and other attributes. This set of interfaces is the minimum required to be implemented by any Wayland compositor.

Some of the most basic interfaces of the Wayland protocol are:[29]

- wl_display – the core global object, a special object to encapsulate the Wayland protocol itself

- wl_registry – the global registry object, in which the compositor registers all the global objects that it wants to be available to all clients

- wl_compositor – an object that represents the compositor, and is in charge of combining the different surfaces into one output

- wl_surface – an object representing a rectangular area on the screen, defined by a location, size and pixel content

- wl_buffer – an object that, when attached to a wl_surface object, provides its displayable content

- wl_output – an object representing the displayable area of a screen

- wl_pointer, wl_keyboard, wl_touch – objects representing different input devices like pointers or keyboards

- wl_seat – an object representing a seat (a set of input/output devices) in multiseat configurations

A typical Wayland client session starts by opening a connection to the compositor using the wl_display object. This is a special local object that represents the connection and does not live within the server. By using its interface the client can request the wl_registry global object from the compositor, where all the global object names live, and bind those that the client is interested in. Usually the client binds at least a wl_compositor object from where it will request one or more wl_surface objects to show the application output on the display.[28]

Wayland extension interfaces

[edit]A Wayland compositor can define and export its own additional interfaces.[29] This feature is used to extend the protocol beyond the basic functionality provided by the core interfaces, and has become the standard way to implement Wayland protocol extensions. Certain compositors can choose to add custom interfaces to provide specialized or unique features. The Wayland reference compositor, Weston, used them to implement new experimental interfaces as a testbed for new concepts and ideas, some of which later became part of the core protocol (such as wl_subsurface interface added in Wayland 1.4[31]).

Extension protocols to the core protocol

[edit]XDG-Shell protocol

[edit]XDG-Shell protocol (see freedesktop.org for XDG) is an extended way to manage surfaces under Wayland compositors (not only Weston). The traditional way to manipulate (maximize, minimize, fullscreen, etc.) surfaces is to use the wl_shell_*() functions, which are part of the core Wayland protocol and live in libwayland-client. An implementation of the xdg-shell protocol, on the contrary, is supposed to be provided by the Wayland compositor. So you will find the xdg-shell-client-protocol.h header in the Weston source tree.

xdg_shell is a protocol aimed to substitute wl_shell in the long term, but will not be part of the Wayland core protocol. It starts as a non-stable API, aimed to be used as a development place at first, and once features are defined as required by several desktop shells, it can be finally made stable. It provides mainly two new interfaces: xdg_surface and xdg_popup. The xdg_surface interface implements a desktop-style window that can be moved, resized, maximized, etc.; it provides a request for creating child/parent relationship. The xdg_popup interface implements a desktop-style popup/menu; an xdg_popup is always transient for another surface, and also has implicit grab.[32]

IVI-Shell protocol

[edit]IVI-Shell is an extension to the Wayland core protocol, targeting in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) devices.[33]

Rendering model

[edit]

The Wayland protocol does not include a rendering API.[34][14][35][36]: 2 Instead, Wayland follows a direct rendering model, in which the client must render the window contents to a buffer shareable with the compositor.[37] For that purpose, the client can choose to do all the rendering by itself, use a rendering library like Cairo or OpenGL, or rely on the rendering engine of high-level widget libraries with Wayland support, such as Qt or GTK. The client can also optionally use other specialized libraries to perform specific tasks, such as Freetype for font rendering.

The resulting buffer with the rendered window contents are stored in a wl_buffer object. The internal type of this object is implementation dependent. The only requirement is that the content data must be shareable between the client and the compositor. If the client uses a software (CPU) renderer and the result is stored in the system memory, then client and compositor can use shared memory to implement the buffer communication without extra copies. The Wayland protocol already natively provides this kind of shared memory buffer through the wl_shm[38] and wl_shm_pool[39] interfaces. The drawback of this method is that the compositor may need to do additional work (usually to copy the shared data to the GPU) to display it, which leads to slower graphics performance.

The most typical case is for the client to render directly into a video memory buffer using a hardware (GPU) accelerated API such as OpenGL, OpenGL ES or Vulkan. Client and compositor can share this GPU-space buffer using a special handler to reference it.[40] This method allows the compositor to avoid the extra data copy through itself of the main memory buffer client-to-compositor-to-GPU method, resulting in faster graphics performance, and is therefore the preferred one. The compositor can further optimize the composition of the final scene to be shown on the display by using the same hardware acceleration API as an API client.

When rendering is completed in a shared buffer, the Wayland client should instruct the compositor to present the rendered contents of the buffer on the display. For this purpose, the client binds the buffer object that stores the rendered contents to the surface object, and sends a "commit" request to the surface, transferring the effective control of the buffer to the compositor.[23] Then the client waits for the compositor to release the buffer (signaled by an event) if it wants to reuse the buffer to render another frame, or it can use another buffer to render the new frame, and, when the rendering is finished, bind this new buffer to the surface and commit its contents.[41]: 7 The procedure used for rendering, including the number of buffers involved and their management, is entirely under the client control.[41]: 7

Comparison with other window systems

[edit]Differences between Wayland and X

[edit]There are several differences between Wayland and X with regard to performance, code maintainability, and security:[42]

- Architecture

- The composition manager is a separate, additional feature in X, while Wayland merges display server and compositor as a single function.[43][35] Also, it incorporates some of the tasks of the window manager, which in X is a separate client-side process.[44]

- Compositing

- Compositing is optional in X, but mandatory in Wayland. Compositing in X is "active"; that is, the compositor must fetch all pixel data, which introduces latency. In Wayland, compositing is "passive", which means the compositor receives pixel data directly from clients.[45]: 8–11

- Rendering

- The X server itself is able to perform rendering, although it can also be instructed to display a rendered window sent by a client. In contrast, Wayland does not expose any API for rendering, but delegates to clients such tasks (including the rendering of fonts, widgets, etc.).[43][35] Window decorations are to be rendered on the client side (e.g., by a graphics toolkit), or on the server side (by the compositor) with the opt-in xdg-decoration protocol, if the compositor chooses to implement such functionality.[46]

- Security

- Wayland isolates the input and output of every window, achieving confidentiality, integrity and availability for both. The original X design lacked these important security features,[11][12][13] although some extensions have been developed trying to mitigate it.[47][48][49]

- Also, with the vast majority of the code running in the client, less code needs to run with root privileges, improving security,[11] although multiple popular Linux distributions now allow the X server to be run without root privileges.[50][51][52][53]

- Networking

- The X Window System is an architecture that was designed at its core to run over a network. Wayland does not offer network transparency by itself;[14] however, a compositor can implement any remote desktop protocol to achieve remote display. In addition, there is research into Wayland image streaming and compression that would provide remote frame buffer access similar to that of VNC.[21]

Compatibility with X

[edit]XWayland is an X Server running as a Wayland client, and thus is capable of displaying native X11 client applications in a Wayland compositor environment.[54][55] This is similar to the way XQuartz runs X applications in macOS's native windowing system. The goal of XWayland is to facilitate the transition from X Window System to Wayland environments, providing a way to run unported applications in the meantime. XWayland was mainlined into X.Org Server version 1.16.[56]

Widget toolkits such as Qt 5 and GTK 3 can switch their graphical back-end at run time,[57] allowing users to choose at load time whether they want to run the application over X or over Wayland. Qt 5 provides the -platform command-line option[58] to that effect, whereas GTK 3 lets users select the desired GDK back-end by setting the GDK_BACKEND Unix environment variable.[57][59]

Wayland compositors

[edit]

kwin_wayland compositor) under Arch LinuxDisplay servers that implement the Wayland display server protocol are also called Wayland compositors because they additionally perform the task of a compositing window manager.

A library called wlroots is a modular Wayland implementation that functions as a base for several compositors.[60]

Some notable Wayland compositors are:

- Weston – an implementation from the Wayland development team. For details about Weston see below.

- Enlightenment had Wayland support since version 0.20[61]

- KWin, the default wayland compositor of KDE Plasma[62]

- Mutter, the default wayland compositor of GNOME[63]

- Sway – a tiling Wayland compositor, based on wlroots; it is a drop-in replacement for the i3 X11 window manager.[64][65][66]

- Hyprland – a tiling Wayland compositor written in C++. Noteworthy features of Hyprland include dynamic tiling, tabbed windows, and a custom renderer that provides window animations, rounded corners, and Dual-Kawase Blur on transparent windows.[67][68]

- Woodland – wlroots-based window-stacking compositor for Wayland written in C, inspired by TinyWL and focused on simplicity and stability.

- niri – a scrollable-tiling Wayland compositor written in Rust.[69]

- labwc – a wlroots-based window-stacking compositor for Wayland, inspired by Openbox. It follows a similar approach and coding style to Sway.[70]

Weston

[edit]Weston is a Wayland compositor previously developed as the reference implementation of the protocol by the Wayland project.[71][72] It is written in C and released under the MIT License.

Weston officially supports only Linux due to dependencies on kernel-specific features such as kernel mode-setting (KMS), the Graphics Execution Manager (GEM), and udev. On Linux, it handles input via evdev and buffer management via Generic Buffer Management (GBM). A prototype port for FreeBSD was announced in 2013.[73]

The compositor supports High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection (HDCP)[74] and uses GEM to share buffers between applications and the compositor. It features a plug-in architecture with "shells" that provide elements like docks and panels.[21] Applications are responsible for rendering their own window decorations.

Weston supports rendering via OpenGL ES[75] or the pixman library for software rendering.[76] The full OpenGL stack is avoided to prevent pulling in GLX and other X Window System dependencies.[77]

A remote desktop interface for Weston was proposed in 2013 by a developer from RealVNC.[78]

Maynard

[edit]

Maynard is a graphical shell and has been written as a plug-in for Weston, just as the GNOME Shell has been written as a plug-in to Mutter.[79]

Raspberry Pi Holdings in collaboration with Collabora released Maynard.[80][81]

libinput

[edit]

The Weston code for handling input devices (keyboards, pointers, touch screens, etc.) was split into its own separate library, called libinput, for which support was first merged in Weston 1.5.[82][83]

Libinput handles input devices for multiple Wayland compositors and also provides a generic X.Org Server input driver. It aims to provide one implementation for multiple Wayland compositors with a common way to handle input events while minimizing the amount of custom input code compositors need to include. libinput provides device detection[clarification needed] (via udev), device handling, input device event processing and abstraction.[84][85]

Version 1.0 of libinput followed version 0.21, and included support for tablets, button sets and touchpad gestures. This version will maintain stable API/ABI.[86]

As GNOME/GTK and KDE Frameworks 5[87] have mainlined the required changes, Fedora 22 will replace X.Org's evdev and Synaptics drivers with libinput.[88]

With version 1.16, the X.Org Server obtained support for the libinput library in form of a wrapper called xf86-input-libinput.[89][90]

Wayland Security Module

[edit]Wayland Security Module is a proposition that resembles the Linux Security Module interface found in the Linux kernel.[91]

Some applications (especially the ones related to accessibility) require privileged capabilities that should work across different Wayland compositors. Currently,[when?] applications under Wayland are generally unable to perform any sensitive tasks such as taking screenshots or injecting input events without going through xdg-desktop-portal or obtaining privileged access to the system. The security model forced by Wayland also creates mouse position problems when attempting to type text in many games.[92]

Wayland Security Module is a way to delegate security decisions within the compositor to a centralized security decision engine.[91]

Adoption

[edit]The Wayland protocol is designed to be simple so that additional protocols and interfaces need to be defined and implemented to achieve a holistic windowing system. While many graphical toolkits already fully support Wayland, the developers of the graphical shells are cooperating with the Wayland developers to create the necessary additional interfaces.

Desktop Linux distributions

[edit]Most major Linux distributions default to using Wayland. Some notable examples are:

- Debian ships Wayland as the default session for GNOME since version 10 (Buster), released 6 July 2019.[93]

- Fedora starting with version 25 (released 22 November 2016) uses Wayland for the default GNOME 3.22 desktop session, with X.Org as a fallback if the graphics driver cannot support Wayland.[94] Fedora uses Wayland as the default for KDE desktop session starting with version 34 (released 27 April 2021)

- Manjaro ships Wayland as default in the Gnome edition of Manjaro 20.2 (Nibia) (released 22 November 2020).[95]

- Raspberry Pi OS, a port of Debian, has offered the option to use Wayland since version 11 (Bullseye), which was released on 3 December 2021. Wayland became the default in version 12 (Bookworm), released on 10 October 2023.

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux ships Wayland as the default session in version 8, released 7 May 2019.[96]

- Ubuntu shipped with Wayland by default in Ubuntu 17.10 (Artful Aardvark).[97] However, Ubuntu 18.04 LTS reverted to X.Org by default due to several issues.[98][99] Since Ubuntu 21.04, Wayland is the default again.[100]

- Slackware Linux included Wayland on 20 February 2020[101] for the development version, -current, which became version 15.0 in 2022. However, Wayland is still not the default.[102]

Toolkit support

[edit]Toolkits supporting Wayland include the following:

- EFL has complete Wayland support, except for selection.[103]

- GTK 3.20 has complete Wayland support.[104]

- Qt 5 has complete Wayland support, and can be used to write both Wayland compositors and Wayland clients.

- SDL support for Wayland debuted with the 2.0.2 release[105] and was enabled by default since version 2.0.4.[106]

- GLFW 3.2 has Wayland support.[107]

- FreeGLUT has initial Wayland support.[108]

- FLTK supports Wayland since version 1.4.0 (Nov. 2024).[109]

Desktop environments

[edit]Desktop environments that have been ported from X to Wayland include GNOME,[110] KDE Plasma[111] and Enlightenment.[112]

GNOME 3.20 was the first version to have a full Wayland session.[113] GNOME 3.22 included much improved Wayland support across GTK, Mutter, and GNOME Shell.[114] GNOME 3.24 shipped support for the proprietary Nvidia drivers under Wayland.[115]

KDE Plasma started supporting Wayland in version 5.[116] Version 5.4 of Plasma was the first with a full Wayland session.[117] In KDE Plasma 6, Wayland became the default.[118]

In November 2015, Enlightenment e20 was announced with full Wayland support.[119][61][120]

Other software

[edit]Other software supporting Wayland includes the following:

- Intelligent Input Bus is working on Wayland support, it could be ready for Fedora 22.[121]

- RealVNC published a Wayland developer preview in July 2014.[78][122][123]

- wayvnc is a VNC server for wlroots-based Wayland compositors.

- Maliit is an input method framework that runs under Wayland.[124][125][126]

- kmscon supports Wayland with wlterm.[127]

- Mesa has Wayland support integrated.[128]

- Eclipse was made to run on Wayland during a GSoC-Project in 2014.[129]

- The Vulkan WSI (Window System Interface) is a set of API calls that serve a similar purpose as EGL does for OpenGL & OpenGL ES or GLX for OpenGL on X11. Vulkan WSI includes support for Wayland from day one: VK_USE_PLATFORM_WAYLAND_KHR. Vulkan clients can run on unmodified Wayland servers, including Weston, GENIVI LayerManager, Mutter / GNOME Shell, Enlightenment, and more. The WSI allows applications to discover the different GPUs on the system, and display the results of GPU rendering to a window system.[130]

- Waydroid (formerly called Anbox-Halium), a container for Android applications to run on Linux distributions using Wayland.

Mobile and embedded hardware

[edit]

Mobile and embedded hardware supporting Wayland includes the following:

- postmarketOS

- GENIVI Alliance: The GENIVI Aliance, now COVESA, for in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) supports Wayland.[131]

- Jolla: Smartphones from Jolla use Wayland. It is also used as standard when Linux Sailfish OS is used with hardware from other vendors or when it is installed into Android devices by users.[132][133][134]

- Tizen: Starting in version 2.x, Tizen supports Wayland in in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) setups.[135] From 3.0 onward, Tizen defaults to Wayland.[136][137]

History

[edit]

Kristian Høgsberg, a Linux graphics and X.Org developer who previously worked on AIGLX and DRI2, started Wayland as a spare-time project in 2008 while working for Red Hat.[138][139][140][141] His stated goal was a system in which "every frame is perfect, by which I mean that applications will be able to control the rendering enough that we'll never see tearing, lag, redrawing or flicker." Høgsberg was driving through the town of Wayland, Massachusetts when the underlying concepts "crystallized", hence the name (Weston and Maynard are also nearby towns in the same area, continuing the reference).[140][142]

In October 2010, Wayland became a freedesktop.org project.[143][144] As part of the migration, the prior Google Group was replaced by the wayland-devel mailing list as the project's central point of discussion and development.

The Wayland client and server libraries were initially released under the MIT License,[145] while the reference compositor Weston and some example clients used the GNU General Public License version 2.[146] Later, all the GPL code was relicensed under the MIT license "to make it easier to move code between the reference implementation and the actual libraries".[147] In 2015 it was discovered that the license text used by Wayland was a slightly different and older version of the MIT license, and the license text was updated to the current version used by the X.Org project (known as MIT Expat License).[6]

Wayland works with all Mesa-compatible drivers with DRI2 support[128] as well as Android drivers via the Hybris project.[148][149][150]

Releases

[edit]| Version | Date | Main features | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wayland | Weston | Wayland Protocols | ||

| 0.85 | 9 February 2012[152] | First release. | ||

| 0.95 | 24 July 2012[153] | Began API stabilization. | ||

| 1.0 | 22 October 2012[154][155] | Stable wayland-client API. | ||

| 1.1 | 15 April 2013[156][157] | Software rendering.[76] FBDEV, RDP backends. | ||

| 1.2 | 12 July 2013[158][159] | Stable wayland-server API. | Color management. Subsurfaces. Raspberry Pi backend. | |

| 1.3 | 11 October 2013[160] | More pixel formats. Support for language bindings. | Android driver support via libhybris. | |

| 1.4 | 23 January 2014[31] | New wl_subcompositor and wl_subsurface interfaces. | Multiple framebuffer formats. logind support for rootless Weston. | |

| 1.5 | 20 May 2014[82] | libinput. Fullscreen shell. | ||

| 1.6 | 19 September 2014[161] | libinput by default. | ||

| 1.7 | 14 February 2015[162][163] | Support for the Wayland presentation extension and for surface roles. IVI shell protocol. | ||

| 1.8 | 2 June 2015[164][165] | Separated headers for core and generated protocol. | Repaint scheduling. Named outputs. Output transformations. Surface-shooting API. | |

| 1.9 | 21 September 2015[166][167] | Updated license. | Updated license. New test framework. Triple-head DRM compositor. linux_dmabuf extension. | 1.0 (2015-11-24)[168] |

| 1.10 | 17 February 2016[169][170] | Drag-and-drop functionality, grouped pointer events.[171] | Video 4 Linux 2, touch input, debugging improvements.[172] | 1.1 (2016-02-16)[173] 1.4 (2016-05-23)[174] |

| 1.11 | 1 June 2016[175][176] | New backup loading routine, new setup logic. | Proxy wrappers, shared memory changes, Doxygen-generated HTML docs. | 1.5 (2016-07-22)[177] 1.7 (2016-08-15)[178] |

| 1.12 | 21 September 2016[179][180] | Debugging support improved. | libweston and libweston-desktop. Pointer locking and confinement. Relative pointer support. | |

| 1.13 | 24 February 2017[181] | The ABI of Weston has been changed, thus the new version was named 2.0.0[182] rather than 1.13.0. | 1.8 (2017-06-12) 1.10 (2017-07-31)[183] | |

| 1.14 | 8 August 2017[184] | Weston 3.0.0[185] was released at the same time. | 1.11 (2017-10-11)[186] 1.13 (2018-02-14)[187] | |

| 1.15 | 9 April 2018[188] | Weston 4.0.0[189] was released at the same time. | 1.14 (2018-05-07)[190] 1.16 (2018-07-30)[191] | |

| 1.16 | 24 August 2018[192] | Weston 5.0.0[193] was released at the same time. | 1.17 (2018-11-12)[194] | |

| 1.17 | 20 March 2019[195] | Weston 6.0.0[196] was released at the same time. | 1.18 (2019-07-25)[197] | |

| 1.18 | 11 February 2020[198] | Weston 7.0.0[199] was released on 2019-08-23. Weston 8.0.0[200] was released on 2020-01-24. Weston 9.0.0[201] was released on 2020-09-04. |

1.19 (2020-02-29)[202] 1.20 (2020-02-29)[203] | |

| 1.19 | 27 January 2021[204] | 1.21 (2021-04-30)[205] 1.24 (2021-11-23)[206] | ||

| 1.20 | 9 December 2021[207] | Weston 10.0.0[208] was released on 2022-02-01. Weston 10.0.5[209] was released on 2023-08-02. |

1.25 (2022-01-28)[210] | |

| 1.21 | 30 June 2022[211] | Weston 11.0.0[212] was released on 2022-09-22. Weston 11.0.3[213] was released on 2023-08-02. |

1.26 (2022-07-07)[214] 1.31 (2022-11-29)[215] | |

| 1.22 | 4 April 2023[216] | Weston 12.0.0[217] was released on 2023-05-17. Weston 12.0.5[218] was released on 2025-04-29. Weston 13.0.0[219] was released on 2023-11-27. Weston 13.0.4[220] was released on 2025-04-25. |

1.32 (2023-07-03)[221] 1.36 (2024-04-26)[222] | |

| 1.23 | 30 May 2024[223] | Weston 14.0.0[224] was released on 2024-09-04. Weston 14.0.2[3] was released on 2025-04-25. |

1.37 (2024-08-31)[225] 1.45 (2025-06-13)[226] | |

| 1.24 | 7 July 2025[2] | |||

| 1.25 | ||||

Unsupported Supported Latest version Future version | ||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (30 September 2008). "Initial commit". Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.24.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). 6 July 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Weston 14.0.2 release". wayland-devel (Mailing list). April 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Wayland & Weston Compositor Ported To DragonFlyBSD - Phoronix". www.phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ "My progress in Wayland compatibility layer". 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Harrington, Bryce (15 September 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.8.93". freedesktop.org (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "wayland/wayland: root/COPYING". gitlab.freedesktop.org. 9 June 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (10 June 2015). "Wayland's MIT License To Be Updated/Corrected". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ a b c "Wayland". Wayland project. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ Sengar, Shivam Singh (16 June 2018). "Wayland v/s Xorg : How Are They Similar & How Are They Different". secjuice. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Kerrisk, Michael (25 September 2012). "XDC2012: Graphics stack security". LWN.net. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ a b Peres, Martin (21 February 2014). "Wayland Compositors - Why and How to Handle Privileged Clients! (Updated on the 2014/02/21)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ a b Graesslin, Martin (23 November 2015). "Looking at the security of Plasma/Wayland". Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Wayland FAQ". Wayland project. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ Michael Larabel (20 May 2009). "The State Of The Wayland Display Server". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ Corbet, Jonathan (5 November 2010). "LPC: Life after X". LWN.net. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (9 November 2010). "Network transparency argument". Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

Wayland isn't a remote rendering API like X, but that doesn't exclude network transparency. Clients render into a shared buffer and then have to tell the compositor (...) what they changed. The compositor can then send the new pixels in that region out over the network. The Wayland protocol is already violently asynchronous, so it should be able to handle a bit of network lag gracefully. Remote fullscreen video viewing or gaming isn't going to work well, [but] I don't know any other display system that handles that well and transparently.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (18 August 2011). "Remote Wayland Server Project: Does It Work Yet?". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Adam (9 November 2010). "[Re:] Ubuntu moving towards Wayland". devel@lists.fedoraproject.org (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Stone, Daniel (28 January 2013). The real story behind Wayland and X (Speech). linux.conf.au 2013. Canberra. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Willis, Nathan (13 February 2013). "LCA: The ways of Wayland". LWN.net. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Aleksandersen, Daniel (28 August 2017). "Remote desktop capabilities set to make a comeback in GNOME on Wayland". Ctrl.blog. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ a b "The Hello Wayland Tutorial". 8 July 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Chapter 4. Wayland Protocol and Model of Operation". The Wayland Protocol. Wire Format.

- ^ a b c d Høgsberg, Kristian. "Chapter 4. Wayland Protocol and Model of Operation". The Wayland Protocol. Basic Principles.

- ^ a b Høgsberg, Kristian (8 May 2024). "protocol/wayland.xml". gitlab.freedesktop.org. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Appendix B. Client API". The Wayland Protocol. Introduction.

- ^ a b Paalanen, Pekka (25 July 2014). "Wayland protocol design: object lifespan". Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Høgsberg, Kristian. "Chapter 4. Wayland Protocol and Model of Operation". The Wayland Protocol. Interfaces.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Chapter 4. Wayland Protocol and Model of Operation". The Wayland Protocol. Versioning.

- ^ a b Høgsberg, Kristian (24 January 2014). "Wayland and Weston 1.4 is out". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "xdg_shell: Adding a new shell protocol". freedesktop.org. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "GENIVI/wayland-ivi-extension". GitHub. 17 November 2021. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Chapter 3. Wayland Architecture". The Wayland Protocol. X vs. Wayland Architecture.

- ^ a b c Vervloesem, Koen (15 February 2012). "FOSDEM: The Wayland display server". LWN.net. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ Barnes, Jesse. "Introduction to Wayland" (PDF). Intel Open Source Technology Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

Does not include a rendering API – Clients use what they want and send buffer handles to the server

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Chapter 3. Wayland Architecture". The Wayland Protocol. Wayland Rendering.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Appendix A. Wayland Protocol Specification". The Wayland Protocol. wl_shm - shared memory support.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Appendix A. Wayland Protocol Specification". The Wayland Protocol. wl_shm_pool - a shared memory pool.

- ^ Paalanen, Pekka (21 November 2012). "On supporting Wayland GL clients and proprietary embedded platforms". Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

Buffer sharing works by creating a handle for a buffer, and passing that handle to another process which then uses the handle to make the GPU access again the same buffer.

- ^ a b Høgsberg, Kristian. "Wayland Documentation 1.3" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Griffith, Eric (7 June 2013). "The Wayland Situation: Facts About X vs. Wayland". Phoronix.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Wayland Architecture". Wayland project. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ Edge, Jake (11 April 2012). "LFCS 2012: X and Wayland". LWN.net. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Wayland/X Compositor Architecture By Example: Enlightenment DR19" (PDF). Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b Graesslin, Martin (7 February 2013). "Client Side Window Decorations and Wayland". Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "X.Org Security". X.Org Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

The X server has long included an extension, SECURITY, which provides support for a simple trusted/untrusted connection model.

- ^ Wiggins, David P. (15 November 1996). "Security Extension Specification". X Consortium Standard. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Walsh, Eamon F. (2009). "X Access Control Extension Specification". Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Debian Moves To Non-Root X.Org Server By Default - Phoronix". www.phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Non root Xorg - Gentoo Wiki". wiki.gentoo.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "X/Rootless - Ubuntu Wiki". wiki.ubuntu.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "1078902 – Xorg without root rights". bugzilla.redhat.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "X Clients under Wayland (XWayland)". Wayland project. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Chapter 5. X11 Application Support". wayland.freedesktop.org. Retrieved 28 October 2025.

- ^ "ANNOUNCE: xorg-server 1.16.0". freedesktop.org. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ a b Høgsberg, Kristian (3 January 2011). "Multiple backends for GTK". Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "QtWayland". Qt Wiki. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Full Wayland support in GTK+". GNOME wiki. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "README.md". wlroots project on GitLab. 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b Larabel, Michael (30 November 2015). "Enlightenment 0.20 Arrives With Full Wayland Support & Better FreeBSD Support". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Plasma 5.21". KDE Community. 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Bump version to 3.13.1". 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Sway". swaywm.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "swaywm/wlroots". GitHub. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ "swaywm/sway". GitHub. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ "Hyprland - ArchWiki". wiki.archlinux.org. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "Hyprland: Dynamic tiling window compositor with the looks". hyprland.org. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "A tour of the niri scrolling-tiling Wayland compositor". lwn.net. Retrieved 10 October 2025.

- ^ "labwc". labwc.github.io. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ Ser, Simon. "Remove "the reference Wayland compositor"". FreeDesktop GitLab. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ "README". gitlab.freedesktop.org. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (16 February 2013). "Wayland Begins Porting Process To FreeBSD". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Adding Content protection support in drm-backend (!48) · Merge Requests · wayland / weston". GitLab. 6 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Paalanen, Pekka (10 March 2012). "What does EGL do in the Wayland stack". Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ a b Larabel, Michael (6 January 2013). "A Software-Based Pixman Renderer For Wayland's Weston". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (9 December 2010). "Blender3D & cursor clamping". Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ a b "[RFC weston] remote access interface module". freedesktop.org. 18 October 2013. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Maynard announcement". 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "2D graphics Wayland/Weston optimizations on the Raspberry Pi". Collabora. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ "Wayland preview". Raspberry Pi. 24 February 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b Høgsberg, Kristian (20 May 2014). "Wayland and Weston 1.5.0 is released". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (12 November 2013). "[RFC] Common input device library". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "libinput". Freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Hutterer, Peter (8 October 2014). Consolidating the input stacks with libinput (Speech). The X.Org Developer Conference 2014. Bordeaux. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Hutterer, Peter (22 February 2015). "libinput: the road to 1.0". Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Libinput support added to Touchpad KCM". 22 February 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Goede, Hans de (23 February 2015). "Libinput now enabled as default xorg driver for F-22 workstation installs". devel@lists.fedoraproject.org (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Hutterer, Peter (24 September 2014). "libinput - a common input stack for Wayland compositors and X.Org drivers". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ de Goede, Hans (1 February 2015). "Replacing xorg input - Drivers with libinput" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ a b Dodier-Lazaro, Steve; Peres, Martin (9 October 2014). Security in Wayland-based Desktop Environments: Privileged Clients, Authorization, Authentication and Sandboxing! (Speech). The X.Org Developer Conference 2014. Bordeaux. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ "Mouse wrap/Capture when playing games under Wayland". 7 July 2025.

- ^ "NewInBuster - Debian Wiki". wiki.debian.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Changes/WaylandByDefault - Fedora Project Wiki". fedoraproject.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Manjaro 20.2 Nibia got released". 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Release notes for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8.0". Red Hat Customer Portal. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "ReleaseNotes for Ubuntu 17.10". Canonical. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Ubuntu 18.04 will revert to long-in-the-tooth Xorg". Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Bionic Beaver 18.04 LTS to use Xorg by default". Canonical. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Ubuntu 21.04 is here". Canonical Ubuntu Blog. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Slackware ChangeLogs". Slackware Linux. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ "The Wait is Over! Slackware 15.0 Stable Hit the Streets". 4 February 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2025.

- ^ "Wayland – Enlightenment". Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "GTK+ Roadmap". Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Lantinga, Sam (8 March 2014). "SDL 2.0.2 RELEASED!". SDL Project. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (9 January 2016). "SDL 2.0.4 Was Quietly Released Last Week With Wayland & Mir By Default". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Berglund, Camilla (8 April 2014). "Implementation for Wayland · Issue #106 · glfw/glfw · GitHub". GitHub. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "FreeGLUT: Implement initial Wayland support". GitHub. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ S, A. "FLTK 1.4.0-1 released on Nov. 18, 2024". FLTK. AlbrechtS.

- ^ "GNOME Initiatives - Wayland". GNOME Wiki. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "KWin/Wayland". KDE Community Wiki. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "Enlightenment - Wayland". Enlightenment.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "ReleasePlanning/FeaturesPlans". GNOME Project. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "A Look At The Exciting Features/Improvements Of GNOME 3.22". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "GNOME Lands Mainline NVIDIA Wayland Support Using EGLStreams". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Plasma's Road to Wayland". 25 July 2014. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Graesslin, Martin (29 June 2015). "Four years later". Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Wallen, Jack (14 February 2024). "The first Linux distribution to deliver a pure KDE Plasma 6 environment is here". ZDNET. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Enlightenment DR 0.20.0 Release". Enlightenment.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "The Enlightenment of Wayland". FOSDEM.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Schaller, Christian (3 July 2014). "Wayland in Fedora Update". blogs.gnome.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "VNC® Wayland Developer Preview". 8 July 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ "RealVNC Wayland developer preview email". freedesktop.org. 9 July 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Maliit Status Update". Posterous. 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "More Maliit Keyboard Improvements: QtQuick2". Murray's Blog. 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Maliit under Wayland". Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "wlterm". Freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ a b Hillesley, p. 3.

- ^ "Eclipse now runs on Wayland". 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Stone, Daniel (16 February 2016). "Vulkan 1.0 specification released with day-one support for Wayland". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Wayland Backend DRM | IVI Layer Management". GENIVI Alliance. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ "The First Jolla Smartphone Runs With Wayland". LinuxG.net. 14 July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ VDVsx [@VDVsx] (13 July 2013). "#sailfishos main components diagram. #Qt5 #Wayland #JollaHQ #Akademy" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Jolla [@JollaHQ] (13 July 2013). "@faenil @PeppeLaKappa @VDVsx our first Jolla will ship with wayland, yes" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "IVI/IVI Setup". Tizen Wiki. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ VanCutsem, Geoffroy (10 July 2013). "[IVI] Tizen IVI 3.0-M1 released". IVI (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Amadeo, Ron (12 May 2017). "The Samsung Z4 is Tizen's new flagship smartphone". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (3 November 2008). "Premature publicity is better than no publicity". Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Interview: Kristian Høgsberg". FOSDEM Archive. 29 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b Hillesley, Richard (13 February 2012). "Wayland - Beyond X". The H Open. Heise Media UK. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian. "Wayland – A New Display Server for Linux". Linux Plumbers Conference, 2009. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017.

- ^ Jenkins, Evan (22 March 2011). "The Linux graphics stack from X to Wayland". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (29 October 2010). "Wayland Becomes A FreeDesktop.org Project". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (29 October 2010). "Moving to freedesktop.org". Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (3 December 2008). "Wayland is now under MIT license". wayland-display-server (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (22 November 2010). "Wayland license clarification". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (19 September 2011). "License update". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Munk, Carsten (11 April 2013). "Wayland utilizing Android GPU drivers on glibc based systems, Part 1". Mer Project. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ Munk, Carsten (8 June 2013). "Wayland utilizing Android GPU drivers on glibc based systems, Part 2". Mer Project. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (11 April 2013). "Jolla Brings Wayland Atop Android GPU Drivers". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Wayland". Wayland.freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (9 February 2012). "[ANNOUNCE] Wayland and Weston 0.85.0 released". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (24 July 2012). "Wayland and Weston 0.95.0 released". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (22 October 2012). "Wayland and Weston 1.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Scherschel, Fabian (23 October 2012). "Wayland's 1.0 milestone fixes graphics protocol". The H Open. Heise Media UK. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (16 April 2013). "Wayland 1.1 Officially Released With Weston 1.1". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (15 April 2013). "1.1 Released". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (13 July 2013). "Wayland 1.2.0 Released, Joined By Weston Compositor". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (12 July 2013). "Wayland and Weston 1.2.0 released". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Høgsberg, Kristian (11 October 2013). "Wayland and Weston 1.3 releases are out". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Paalanen, Pekka (19 September 2014). "Wayland and Weston 1.6.0 released". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (14 February 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.7.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (14 February 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 1.7.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (2 June 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.8.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (2 June 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 1.8.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (21 September 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.9.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (21 September 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 1.9.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (24 November 2015). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (17 February 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.10.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (17 February 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 1.10.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Nestor, Marius (18 February 2016). "Wayland 1.10 Display Server Officially Released, Wayland 1.11 Arrives in May 2016". Softpedia. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (16 February 2016). "Wayland 1.10 Officially Released". Phoronix.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (16 February 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.1". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (23 May 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.4". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (1 June 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.11.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (1 June 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 1.11.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (22 July 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.5". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (15 August 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.7". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (21 September 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.12.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (21 September 2016). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 1.12.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (21 February 2017). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.13.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (25 February 2017). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 2.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (31 July 2017). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.10". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (8 August 2017). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.14.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Harrington, Bryce (8 August 2017). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 3.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (11 October 2017). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.11". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (14 February 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.13". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Foreman, Derek (9 April 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.15.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Foreman, Derek (9 April 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 4.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (7 May 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.14". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (30 July 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.16". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Foreman, Derek (24 August 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.16.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Foreman, Derek (24 August 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 5.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (12 November 2018). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.17". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Foreman, Derek (28 March 2019). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.17.0" (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Foreman, Derek (21 March 2019). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 6.0.0" (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (25 July 2019). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.18". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (11 February 2020). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.18" (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Ser, Simon (23 August 2019). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 7.0.0" (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Ser, Simon (24 January 2020). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 8.0.0" (Mailing list). Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Ser, Simon (4 September 2020). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 9.0.0" (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (29 February 2020). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.19". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (29 February 2020). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.20". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (27 January 2021). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.19.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (30 April 2021). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.21". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (23 November 2021). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.24". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (27 January 2021). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.20.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Ser, Simon (1 February 2022). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 10.0.0" (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Vlad, Marius (2 August 2023). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 10.0.5". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (28 January 2022). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.25". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (30 June 2022). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.21.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (22 September 2022). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 11.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Vlad, Marius (2 August 2023). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 11.0.3". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (7 July 2022). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.26". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (29 November 2022). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.31". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (4 April 2023). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.22.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list). Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Vlad, Marius (17 May 2023). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 12.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ "Weston 12.0.5 release". wayland-devel (Mailing list). April 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Vlad, Marius (28 November 2023). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 13.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ "Weston 13.0.4 release". wayland-devel (Mailing list). April 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (3 July 2023). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.32". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (26 April 2024). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.36". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ser, Simon (30 May 2024). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland 1.23.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Vlad, Marius (4 September 2024). "[ANNOUNCE] weston 14.0.0". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ Ådahl, Jonas (31 August 2024). "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.37". wayland-devel (Mailing list).

- ^ "[ANNOUNCE] wayland-protocols 1.45". Wayland-devel (Mailing list). 13 June 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

External links

[edit]Wayland (protocol)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

Wayland is a communication protocol that defines the inter-process communication (IPC) between client applications and a display server known as the compositor, serving as a modern replacement for the X11 protocol in managing input events, output rendering, and window management on Linux and other Unix-like operating systems.[1] In this model, the compositor acts as the central server that receives rendered content from clients and composites it for display, while also routing user input directly to the appropriate applications.[3] The primary purpose of Wayland is to establish a secure and efficient foundation for graphical user interfaces by emphasizing direct rendering, where clients generate their own graphics buffers locally using hardware acceleration and share only the necessary metadata or buffer handles with the compositor, thereby minimizing unnecessary data copying and reducing latency compared to traditional systems.[9] This approach enhances performance and security by isolating clients from direct access to the display hardware or other applications' inputs, preventing issues like unauthorized screen captures or keystroke logging that were prevalent in older protocols.[3] Wayland was initiated in 2008 by Kristian Høgsberg, a developer at Red Hat and contributor to X.Org, as a response to X11's accumulated bloat from decades of extensions and its inherent security vulnerabilities, such as unauthenticated access allowing any client to monitor or manipulate others.[10] In the Wayland ecosystem, clients handle their own rendering and notify the compositor of changes to specific surface regions, enabling the compositor to efficiently blend multiple clients' outputs without redundant processing.[9] The compositor, in turn, manages the final display composition across multiple clients to create a cohesive desktop environment.[3]Design Principles

Wayland's design is grounded in the principle of simplicity, manifested through a minimal core protocol that provides only the essential interfaces necessary for basic operations such as surface creation, buffer management, and input event handling. Unlike X11, which evolved into a complex system burdened by decades of accumulated extensions and feature creep, Wayland deliberately limits its core to around 30 requests, promoting extensibility via separate protocols for advanced features. This streamlined approach reduces implementation complexity for both clients and compositors, fostering easier maintenance and innovation while avoiding the bloat that plagued its predecessor.[11][12] Security is a foundational pillar of Wayland's architecture, achieved by denying clients direct access to global resources like keyboard or mouse grabs and overlays. The compositor acts as a trusted intermediary, enforcing strict isolation between clients to prevent one application from intercepting or injecting input intended for another, thereby mitigating risks such as keylogging or unauthorized screen overlays that were exploitable in X11's more permissive model. This design ensures that input events are routed exclusively to the intended surface, enhancing overall system integrity without relying on client-side permissions.[11][13] Efficiency is prioritized through a direct rendering paradigm, where clients leverage the GPU to render content straight into shared buffers using APIs like EGL, eliminating the need for server-mediated drawing commands. The compositor intervenes solely for final composition—blending these buffers into the display output—which drastically cuts down on latency, bandwidth usage, and CPU involvement compared to X11's indirect rendering overhead. This model aligns with contemporary hardware capabilities, enabling smoother animations and reduced power consumption, particularly on resource-constrained devices.[11][12] At its core, Wayland employs a compositor-centric model that delegates all aspects of window management, including decoration, stacking, and layout, to the compositor rather than distributing these responsibilities across clients. This centralization empowers compositors to optimize for specific hardware and user needs, such as seamless hardware acceleration integration, while simplifying client logic to focus purely on content rendering. By contrast with X11's distributed client-server dynamics, this shift promotes cohesive desktop environments and facilitates consistent handling of modern features like multi-monitor support.[11][13]Technical Architecture

Core Protocol

The Wayland core protocol establishes the foundational communication mechanism between clients and the compositor in a display server environment, emphasizing simplicity and efficiency over legacy features. Defined entirely within the wayland.xml schema file, the protocol specifies a set of interfaces, requests, and events that enable basic surface management, buffer handling, input routing, and display configuration. This XML is processed by the wayland-scanner tool to generate C language bindings for both client and server sides, ensuring type-safe implementations. Messages are serialized and exchanged asynchronously over Unix domain sockets, using a wire format that includes a 32-bit object ID, followed by a 16-bit message size and 16-bit opcode, and variable-length arguments such as integers, strings, or file descriptors.[12] Central to the protocol is the wl_display interface, a singleton object that serves as the entry point for client connections. It manages message dispatching, synchronization via roundtrip requests (e.g., sync and done events for confirming message delivery), and error reporting. Clients initiate interaction by connecting to the compositor's socket and receiving an initial wl_display object with ID 1; from there, they can issue a get_registry request to obtain a wl_registry proxy for discovering compositor-provided globals. The wl_registry interface enumerates available global objects through its global event, which includes the interface name, version, and name; clients then bind to these globals using the bind request, creating new proxy objects with client-assigned IDs. This object-oriented model ensures that all interactions occur via method-like requests on specific objects, with the compositor responding through events. Surface creation and management rely on the wl_compositor and wl_surface interfaces. The wl_compositor global allows clients to create wl_surface objects via its create_surface request, where each wl_surface represents a basic, opaque drawing area without inherent window management semantics. Clients attach content to a surface by creating a wl_buffer—typically via wl_shm.create_pool and pool.create_buffer for shared memory-backed buffers—and issuing an attach request to associate it with the surface, specifying offset and dimensions. The wl_shm interface facilitates efficient buffer sharing using POSIX shared memory (shm_open and mmap), supporting formats like XRGB8888 for direct rendering without unnecessary copies. Clients can use the wl_surface.damage request to indicate changed regions on a surface, allowing the compositor to optimize repaints. However, optimization remains the application's responsibility. Updates to a surface's state, including attachments and transformations, are applied atomically through the commit request, ensuring the compositor sees a consistent state without partial renders—pending changes are queued until commit, at which point frame events signal rendering completion for vertical blank synchronization.[12] Display and input aspects are handled by the wl_output and wl_seat globals, respectively. The wl_output interface, bound from the registry, provides mode events detailing resolutions, refresh rates, and physical properties like subpixel layout, along with geometry events for positioning relative to other outputs; it enables clients to adapt content to multi-monitor setups. For input, the wl_seat interface advertises device capabilities (pointer, keyboard, touch) via its capabilities event and offers factory requests to obtain device-specific proxies, such as wl_pointer for motion and button events or wl_keyboard for key presses—events include timestamps and serials for ordering. These interfaces ensure direct, low-latency forwarding of input from the compositor to the relevant surface under the pointer. Error handling is standardized to maintain robustness, with the compositor issuing wl_display.error events for violations such as invalid object IDs, out-of-bounds arguments, or unsupported requests; each error includes a 32-bit code from a predefined enum (e.g., WL_DISPLAY_ERROR_INVALID_OBJECT or WL_DISPLAY_ERROR_INVALID_METHOD) and a descriptive string. Clients must validate responses and handle dispatch errors gracefully, as the protocol assumes no automatic recovery mechanisms. This core set of interfaces forms the minimal foundation, upon which extensions can build without altering the base wire protocol.[12]Extension Protocols