Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Methylation

View on WikipediaMethylation, in the chemical sciences, is the addition of a methyl group on a substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replacing a hydrogen atom. These terms are commonly used in chemistry, biochemistry, soil science, and biology.

In biological systems, methylation is catalyzed by enzymes; such methylation can be involved in modification of heavy metals, regulation of gene expression, regulation of protein function, and RNA processing. In vitro methylation of tissue samples is also a way to reduce some histological staining artifacts. The reverse of methylation is demethylation.

In biology

[edit]In biological systems, methylation is accomplished by enzymes. Methylation can modify heavy metals and can regulate gene expression, RNA processing, and protein function. It is a key process underlying epigenetics. Sources of methyl groups include S-methylmethionine, methyl folate, methyl B12, trimethylglycine.[1]

Methanogenesis

[edit]Methanogenesis, the process that generates methane from CO2, involves a series of methylation reactions. These reactions are caused by a set of enzymes harbored by a family of anaerobic microbes.[2]

In reverse methanogenesis, methane is the methylating agent.[3]

O-methyltransferases

[edit]A wide variety of phenols undergo O-methylation to give anisole derivatives. This process, catalyzed by such enzymes as caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase, is a key reaction in the biosynthesis of lignols, percursors to lignin, a major structural component of plants.

Plants produce flavonoids and isoflavones with methylations on hydroxyl groups, i.e. methoxy bonds. This 5-O-methylation affects the flavonoid's water solubility. Examples are 5-O-methylgenistein, 5-O-methylmyricetin, and 5-O-methylquercetin (azaleatin).

Proteins

[edit]Along with ubiquitination and phosphorylation, methylation is a major biochemical process for modifying protein function. The most prevalent protein methylations affect arginine and lysine residue of specific histones. Otherwise histidine, glutamate, asparagine, cysteine are susceptible to methylation. Some of these products include S-methylcysteine, two isomers of N-methylhistidine, and two isomers of N-methylarginine.[4]

Methionine synthase

[edit]

Methionine synthase regenerates methionine (Met) from homocysteine (Hcy). The overall reaction transforms 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (N5-MeTHF) into tetrahydrofolate (THF) while transferring a methyl group to Hcy to form Met. Methionine Syntheses can be cobalamin-dependent and cobalamin-independent: Plants have both, animals depend on the methylcobalamin-dependent form.

In methylcobalamin-dependent forms of the enzyme, the reaction proceeds by two steps in a ping-pong reaction. The enzyme is initially primed into a reactive state by the transfer of a methyl group from N5-MeTHF to Co(I) in enzyme-bound cobalamin ((Cob), also known as vitamine B12)), forming methyl-cobalamin (Me-Cob) that now contains Me-Co(III) and activating the enzyme. Then, a Hcy that has coordinated to an enzyme-bound zinc to form a reactive thiolate reacts with the Me-Cob. The activated methyl group is transferred from Me-Cob to the Hcy thiolate, which regenerates Co(I) in Cob, and Met is released from the enzyme.[5]

Heavy metals: arsenic, mercury, cadmium

[edit]Biomethylation is the pathway for converting some heavy elements into more mobile or more lethal derivatives that can enter the food chain. The biomethylation of arsenic compounds starts with the formation of methanearsonates. Thus, trivalent inorganic arsenic compounds are methylated to give methanearsonate. S-adenosyl methionine is the methyl donor. The methanearsonates are the precursors to dimethylarsonates, again by the cycle of reduction (to methylarsonous acid) followed by a second methylation.[6] Related pathways are found in the microbial methylation of mercury to methylmercury.

Epigenetic methylation

[edit]DNA methylation

[edit]DNA methylation is the conversion of the cytosine to 5-methylcytosine. The formation of Me-CpG is catalyzed by the enzyme DNA methyltransferase. In vertebrates, DNA methylation typically occurs at CpG sites (cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites—that is, sites where a cytosine is directly followed by a guanine in the DNA sequence). In mammals, DNA methylation is common in body cells,[7] and methylation of CpG sites seems to be the default.[8][9] Human DNA has about 80–90% of CpG sites methylated, but there are certain areas, known as CpG islands, that are CG-rich (high cytosine and guanine content, made up of about 65% CG residues), wherein none is methylated. These are associated with the promoters of 56% of mammalian genes, including all ubiquitously expressed genes. One to two percent of the human genome are CpG clusters, and there is an inverse relationship between CpG methylation and transcriptional activity. Methylation contributing to epigenetic inheritance can occur through either DNA methylation or protein methylation. Improper methylations of human genes can lead to disease development,[10][11] including cancer.[12][13]

In honey bees, DNA methylation is associated with alternative splicing and gene regulation based on functional genomic research published in 2013.[14] In addition, DNA methylation is associated with expression changes in immune genes when honey bees were under lethal viral infection.[15] Several review papers have been published on the topics of DNA methylation in social insects.[16][17]

RNA methylation

[edit]RNA methylation occurs in different RNA species viz. tRNA, rRNA, mRNA, tmRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, miRNA, and viral RNA. Different catalytic strategies are employed for RNA methylation by a variety of RNA-methyltransferases. RNA methylation is thought to have existed before DNA methylation in the early forms of life evolving on earth.[18]

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most common and abundant methylation modification in RNA molecules (mRNA) present in eukaryotes. 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) also commonly occurs in various RNA molecules. Recent data strongly suggest that m6A and 5-mC RNA methylation affects the regulation of various biological processes such as RNA stability and mRNA translation,[19] and that abnormal RNA methylation contributes to etiology of human diseases.[20]

In social insects such as honey bees, RNA methylation is studied as a possible epigenetic mechanism underlying aggression via reciprocal crosses.[21]

Protein methylation

[edit]Protein methylation typically takes place on arginine or lysine amino acid residues in the protein sequence.[22] Arginine can be methylated once (monomethylated arginine) or twice, with either both methyl groups on one terminal nitrogen (asymmetric dimethylarginine) or one on both nitrogens (symmetric dimethylarginine), by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs). Lysine can be methylated once, twice, or three times by lysine methyltransferases. Protein methylation has been most studied in the histones. The transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine to histones is catalyzed by enzymes known as histone methyltransferases. Histones that are methylated on certain residues can act epigenetically to repress or activate gene expression.[23][24] Protein methylation is one type of post-translational modification.

Evolution

[edit]Methyl metabolism is very ancient and can be found in all organisms on earth, from bacteria to humans, indicating the importance of methyl metabolism for physiology.[25] Indeed, pharmacological inhibition of global methylation in species ranging from human, mouse, fish, fly, roundworm, plant, algae, and cyanobacteria causes the same effects on their biological rhythms, demonstrating conserved physiological roles of methylation during evolution.[26]

In chemistry

[edit]The term methylation in organic chemistry refers to the alkylation process used to describe the delivery of a CH3 group.[27]

Electrophilic methylation

[edit]Methylations are commonly performed using electrophilic methyl sources such as iodomethane,[28] dimethyl sulfate,[29][30] dimethyl carbonate,[31] or tetramethylammonium chloride.[32] Less common but more powerful (and more dangerous) methylating reagents include methyl triflate,[33] diazomethane,[34] and methyl fluorosulfonate (magic methyl). These reagents all react via SN2 nucleophilic substitutions. For example, a carboxylate may be methylated on oxygen to give a methyl ester; an alkoxide salt RO− may be likewise methylated to give an ether, ROCH3; or a ketone enolate may be methylated on carbon to produce a new ketone.

The Purdie methylation is a specific for the methylation at oxygen of carbohydrates using iodomethane and silver oxide.[35]

Eschweiler–Clarke methylation

[edit]The Eschweiler–Clarke reaction is a method for methylation of amines.[36] This method avoids the risk of quaternization, which occurs when amines are methylated with methyl halides.

Diazomethane and trimethylsilyldiazomethane

[edit]Diazomethane and the safer analogue trimethylsilyldiazomethane methylate carboxylic acids, phenols, and even alcohols:

The method offers the advantage that the side products are easily removed from the product mixture.[37]

Nucleophilic methylation

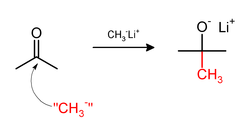

[edit]Methylation sometimes involve use of nucleophilic methyl reagents. Strongly nucleophilic methylating agents include methyllithium (CH3Li)[38] or Grignard reagents such as methylmagnesium bromide (CH3MgX).[39] For example, CH3Li will add methyl groups to the carbonyl (C=O) of ketones and aldehyde.:

Milder methylating agents include tetramethyltin, dimethylzinc, and trimethylaluminium.[40]

See also

[edit]Biology topics

[edit]- Bisulfite sequencing – the biochemical method used to determine the presence or absence of methyl groups on a DNA sequence

- MethDB DNA Methylation Database

- Microscale thermophoresis – a biophysical method to determine the methylisation state of DNA[41]

- Remethylation, the reversible removal of methyl group in methionine and 5-methylcytosine

Organic chemistry topics

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ragsdale, Stephen W. (2008). "Catalysis of Methyl Group Transfers Involving Tetrahydrofolate and B12". Folic Acid and Folates. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 79. pp. 293–324. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(08)00410-X. ISBN 978-0-12-374232-2. PMC 3037834. PMID 18804699.

- ^ Thauer, R. K., "Biochemistry of Methanogenesis: a Tribute to Marjory Stephenson", Microbiology, 1998, volume 144, pages 2377-2406.

- ^ Timmers, Peer H. A.; Welte, Cornelia U.; Koehorst, Jasper J.; Plugge, Caroline M.; Jetten, Mike S. M.; Stams, Alfons J. M. (2017). "Reverse Methanogenesis and Respiration in Methanotrophic Archaea". Archaea. 2017: 1–22. doi:10.1155/2017/1654237. hdl:1822/47121. PMC 5244752. PMID 28154498.

- ^ Clarke, Steven G. (2018). "The ribosome: A hot spot for the identification of new types of protein methyltransferases". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 293 (27): 10438–10446. doi:10.1074/jbc.AW118.003235. PMC 6036201. PMID 29743234.

- ^ Matthews, R. G.; Smith, A. E.; Zhou, Z. S.; Taurog, R. E.; Bandarian, V.; Evans, J. C.; Ludwig, M. (2003). "Cobalamin-Dependent and Cobalamin-Independent Methionine Synthases: Are There Two Solutions to the Same Chemical Problem?". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 86 (12): 3939–3954. doi:10.1002/hlca.200390329.

- ^ Styblo, M.; Del Razo, L. M.; Vega, L.; Germolec, D. R.; LeCluyse, E. L.; Hamilton, G. A.; Reed, W.; Wang, C.; Cullen, W. R.; Thomas, D. J. (2000). "Comparative toxicity of trivalent and pentavalent inorganic and methylated arsenicals in rat and human cells". Archives of Toxicology. 74 (6): 289–299. Bibcode:2000ArTox..74..289S. doi:10.1007/s002040000134. PMID 11005674. S2CID 1025140.

- ^ Tost J (2010). "DNA methylation: an introduction to the biology and the disease-associated changes of a promising biomarker". Mol Biotechnol. 44 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1007/s12033-009-9216-2. PMID 19842073. S2CID 20307488.

- ^ Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, Ye Z, Ngo QM, Edsall L, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Stewart R, Ruotti V, Millar AH, Thomson JA, Ren B, Ecker JR (November 2009). "Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences". Nature. 462 (7271): 315–22. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..315L. doi:10.1038/nature08514. PMC 2857523. PMID 19829295.

- ^ Stadler MB, Murr R, Burger L, Ivanek R, Lienert F, Schöler A, van Nimwegen E, Wirbelauer C, Oakeley EJ, Gaidatzis D, Tiwari VK, Schübeler D (December 2011). "DNA-binding factors shape the mouse methylome at distal regulatory regions". Nature. 480 (7378): 490–5. doi:10.1038/nature11086. PMID 22170606.

- ^ Rotondo JC, Selvatici R, Di Domenico M, Marci R, Vesce F, Tognon M, Martini F (September 2013). "Methylation loss at H19 imprinted gene correlates with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene promoter hypermethylation in semen samples from infertile males". Epigenetics. 8 (9): 990–7. doi:10.4161/epi.25798. PMC 3883776. PMID 23975186.

- ^ Rotondo JC, Bosi S, Bazzan E, Di Domenico M, De Mattei M, Selvatici R, Patella A, Marci R, Tognon M, Martini F (December 2012). "Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene promoter hypermethylation in semen samples of infertile couples correlates with recurrent spontaneous abortion". Human Reproduction. 27 (12): 3632–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/des319. hdl:11392/1689715. PMID 23010533.

- ^ Rotondo JC, Borghi A, Selvatici R, Magri E, Bianchini E, Montinari E, Corazza M, Virgili A, Tognon M, Martini F (2016). "Hypermethylation-Induced Inactivation of the IRF6 Gene as a Possible Early Event in Progression of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma Associated With Lichen Sclerosus". JAMA Dermatology. 152 (8): 928–33. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1336. PMID 27223861.

- ^ Rotondo JC, Borghi A, Selvatici R, Mazzoni E, Bononi I, Corazza M, Kussini J, Montinari E, Gafà R, Tognon M, Martini F (2018). "Association of Retinoic Acid Receptor β Gene With Onset and Progression of Lichen Sclerosus-Associated Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma". JAMA Dermatology. 154 (7): 819–823. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1373. PMC 6128494. PMID 29898214.

- ^ Li-Byarlay, Hongmei; Li, Yang; Stroud, Hume; Feng, Suhua; Newman, Thomas C.; Kaneda, Megan; Hou, Kirk K.; Worley, Kim C.; Elsik, Christine G.; Wickline, Samuel A.; Jacobsen, Steven E.; Ma, Jian; Robinson, Gene E. (30 July 2013). "RNA interference knockdown of DNA methyl-transferase 3 affects gene alternative splicing in the honey bee". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (31): 12750–12755. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11012750L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1310735110. PMC 3732956. PMID 23852726.

- ^ Li-Byarlay, Hongmei; Boncristiani, Humberto; Howell, Gary; Herman, Jake; Clark, Lindsay; Strand, Micheline K.; Tarpy, David; Rueppell, Olav (24 September 2020). "Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Dynamics of Honey Bees in Response to Lethal Viral Infection". Frontiers in Genetics. 11 566320. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.566320. PMC 7546774. PMID 33101388.

- ^ Li-Byarlay, Hongmei (19 May 2016). "The Function of DNA Methylation Marks in Social Insects". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4: 57. Bibcode:2016FrEEv...4...57L. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00057.

- ^ Wang, Ying; Li-Byarlay, Hongmei (2015). Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Nutrition in Honey Bees. Advances in Insect Physiology. Vol. 49. pp. 25–58. doi:10.1016/bs.aiip.2015.06.002. ISBN 978-0-12-802586-4.

- ^ Rana, Ajay K.; Ankri, Serge (6 June 2016). "Reviving the RNA World: An Insight into the Appearance of RNA Methyltransferases". Frontiers in Genetics. 7: 99. doi:10.3389/fgene.2016.00099. PMC 4893491. PMID 27375676.

- ^ Choi, Junhong; Ieong, Ka-Weng; Demirci, Hasan; Chen, Jin; Petrov, Alexey; Prabhakar, Arjun; O'Leary, Seán E; Dominissini, Dan; Rechavi, Gideon; Soltis, S Michael; Ehrenberg, Måns; Puglisi, Joseph D (February 2016). "N6-methyladenosine in mRNA disrupts tRNA selection and translation-elongation dynamics". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 23 (2): 110–115. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3148. PMC 4826618. PMID 26751643.

- ^ Stewart, Kendal (15 September 2017). "Methylation (MTHFR) Testing & Folate Deficiency". Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Bresnahan, Sean T.; Lee, Ellen; Clark, Lindsay; Ma, Rong; Rangel, Juliana; Grozinger, Christina M.; Li-Byarlay, Hongmei (12 June 2023). "Examining parent-of-origin effects on transcription and RNA methylation in mediating aggressive behavior in honey bees (Apis mellifera)". BMC Genomics. 24 (1): 315. doi:10.1186/s12864-023-09411-4. PMC 10258952. PMID 37308882.

- ^ Walsh, Christopher (2006). "Protein Methylation". Posttranslational Modification of Proteins: Expanding Nature's Inventory. Roberts and Company Publishers. pp. 121–149. ISBN 978-0-9747077-3-0.

- ^ Grewal, Shiv IS; Rice, Judd C (June 2004). "Regulation of heterochromatin by histone methylation and small RNAs". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 16 (3): 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2004.04.002. PMID 15145346.

- ^ Nakayama, Jun-ichi; Rice, Judd C.; Strahl, Brian D.; Allis, C. David; Grewal, Shiv I. S. (6 April 2001). "Role of Histone H3 Lysine 9 Methylation in Epigenetic Control of Heterochromatin Assembly". Science. 292 (5514): 110–113. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..110N. doi:10.1126/science.1060118. PMID 11283354.

- ^ Kozbial, Piotr Z; Mushegian, Arcady R (December 2005). "Natural history of S-adenosylmethionine-binding proteins". BMC Structural Biology. 5 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-5-19. PMC 1282579. PMID 16225687.

- ^ Fustin, Jean-Michel; Ye, Shiqi; Rakers, Christin; Kaneko, Kensuke; Fukumoto, Kazuki; Yamano, Mayu; Versteven, Marijke; Grünewald, Ellen; Cargill, Samantha J.; Tamai, T. Katherine; Xu, Yao; Jabbur, Maria Luísa; Kojima, Rika; Lamberti, Melisa L.; Yoshioka-Kobayashi, Kumiko; Whitmore, David; Tammam, Stephanie; Howell, P. Lynne; Kageyama, Ryoichiro; Matsuo, Takuya; Stanewsky, Ralf; Golombek, Diego A.; Johnson, Carl Hirschie; Kakeya, Hideaki; van Ooijen, Gerben; Okamura, Hitoshi (6 May 2020). "Methylation deficiency disrupts biological rhythms from bacteria to humans". Communications Biology. 3 (1): 211. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-0942-0. PMC 7203018. PMID 32376902.

- ^ "Aromatic Substitution, Nucleophilic and Organometallic". March's Advanced Organic Chemistry. 2006. pp. 853–933. doi:10.1002/9780470084960.ch13. ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1.

- ^ Vyas, G. N.; Shah, N. M. (1951). "Quninacetophenone monomethyl ether". Organic Syntheses. 31: 90. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.031.0090.

- ^ Hiers, G. S. (1929). "Anisole". Organic Syntheses. 9: 12. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.009.0012.

- ^ Icke, Roland N.; Redemann, Ernst; Wisegarver, Burnett B.; Alles, Gordon A. (1949). "m-Methoxybenzaldehyde". Organic Syntheses. 29: 63. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.029.0063.

- ^ Tundo, Pietro; Selva, Maurizio; Bomben, Andrea (1999). "Mono-C-methylathion of arylacetonitriles and methyl arylacetates by dimethyl carbonate: a general method for the synthesis of pure 2-arylpropionic acids. 2-Phenylpropionic acid". Organic Syntheses. 76: 169. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.076.0169.

- ^ Nenad, Maraš; Polanc, Slovenko; Kočevar, Marijan (2008). "Microwave-assisted methylation of phenols with tetramethylammonium chloride in the presence of K2CO3 or Cs2CO3". Tetrahedron. 64 (51): 11618–11624. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.024.

- ^ Poon, Kevin W. C.; Albiniak, Philip A.; Dudley, Gregory B. (2007). "Protection of alcohols using 2-benzyloxy-1-methylpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfanonate: Methyl (R)-(-)-3-benzyloxy-2-methyl propanoate". Organic Syntheses. 84: 295. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.084.0295.

- ^ Neeman, M.; Johnson, William S. (1961). "Cholestanyl methyl ether". Organic Syntheses. 41: 9. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.041.0009.

- ^ Purdie, T.; Irvine, J. C. (1903). "C.?The alkylation of sugars". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 83: 1021–1037. doi:10.1039/CT9038301021.

- ^ Icke, Roland N.; Wisegarver, Burnett B.; Alles, Gordon A. (1945). "β-Phenylethyldimethylamine". Organic Syntheses. 25: 89. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.025.0089.

- ^ Shioiri T, Aoyama T, Snowden T (2001). "Trimethylsilyldiazomethane". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. e-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rt298.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-93623-7.

- ^ Lipsky, Sharon D.; Hall, Stan S. (1976). "Aromatic Hydrocarbons from aromatic ketones and aldehydes: 1,1-Diphenylethane". Organic Syntheses. 55: 7. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.055.0007.

- ^ Grummitt, Oliver; Becker, Ernest I. (1950). "trans-1-Phenyl-1,3-butadiene". Organic Syntheses. 30: 75. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.030.0075.

- ^ Negishi, Ei-ichi; Matsushita, Hajime (1984). "Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of 1,4-Dienes by Allylation of Alkenyalane: α-Farnesene". Organic Syntheses. 62: 31. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.062.0031.

- ^ Wienken CJ, Baaske P, Duhr S, Braun D (2011). "Thermophoretic melting curves quantify the conformation and stability of RNA and DNA". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (8): e52. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr035. PMC 3082908. PMID 21297115.

External links

[edit]- deltaMasses Detection of Methylations after Mass Spectrometry

Methylation

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Mechanisms

Methylation is a fundamental chemical reaction in organic chemistry involving the transfer of a methyl group (CH₃) from a donor molecule to a substrate, thereby modifying its structure or properties.[4] This process is a specific type of alkylation where the methyl group replaces a hydrogen atom or attaches to a nucleophilic site on the substrate.[5] The basic mechanism of methylation typically proceeds via an SN2-type nucleophilic substitution, in which the substrate acts as a nucleophile attacking the electrophilic carbon of the methyl donor, such as a methyl halide (CH₃X), leading to inversion of configuration if applicable and displacement of the leaving group (X).[6] Alternatively, in cases where the methyl group is activated, an electrophilic attack by the methyl donor on a nucleophilic substrate can occur.[7] The general reaction can be represented as: where R-Nu represents the nucleophilic substrate and X is a leaving group like iodide./Chapters/Chapter_07:_Alkyl_Halides_and_Nucleophilic_Substitution/7.10:_The_SN2_Mechanism) Methylation reactions form various types of bonds depending on the substrate's nucleophilic site, including C-methylation (attachment to carbon, e.g., alkylation of enolates to form new C-C bonds), N-methylation (attachment to nitrogen, e.g., formation of N-methylamines from amines), O-methylation (attachment to oxygen, e.g., synthesis of anisole from phenol), and S-methylation (attachment to sulfur, e.g., formation of methyl sulfides from thiols)./09%3A_Substitution_and_Elimination_Reactions_of_Alkyl_Halides/9.14%3A_Biological_Methylating_Reagents)[8] Thermodynamically, methylation reactions are influenced by bond dissociation energies (BDEs), which indicate bond stability under homolytic cleavage. For instance, the C-H BDE in methane is approximately 105 kcal/mol, while the C-C BDE in ethane (representing a C-CH₃ bond) is about 90 kcal/mol, suggesting that C-CH₃ bonds are relatively weaker and less stable compared to C-H bonds.[9][10] This difference affects the energetics of radical-mediated processes but underscores the overall feasibility of ionic methylation pathways in synthetic applications.Methyl Group Donors and Acceptors

In biological systems, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) serves as the primary and universal methyl group donor for a wide array of methyltransfer reactions, facilitated by its sulfonium center which provides the electrophilic methyl group.[11] This cofactor is essential for enzymatic processes involving the transfer of the methyl unit to diverse substrates, ensuring controlled and specific reactivity under physiological conditions.[12] In organic chemistry, common synthetic methyl donors include dimethyl sulfate (DMS) and methyl iodide (CH3I), which act as electrophilic agents in alkylation reactions. DMS, a diester of sulfuric acid, is widely used in industrial-scale methylations due to its availability and reactivity, though it requires careful handling owing to its high toxicity and classification as a probable human carcinogen based on animal studies showing nasal and respiratory tumors.[13] CH3I, a simple alkyl halide, offers superior reactivity as a methylating agent, often preferred in laboratory settings for its efficiency in SN2-type displacements, but it poses significant risks as a neurotoxin capable of causing delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms even at low exposure levels.[14] For milder applications, such as selective O-methylation of phenols under microwave-assisted conditions, tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) functions as a quaternary ammonium-based donor, providing a safer alternative with reduced toxicity compared to traditional agents.[15] The reactivity of these donors follows a general scale based on the electrophilicity of the methyl carbon and the quality of the leaving group: CH3I > DMS > SAM, reflecting the ease of nucleophilic attack where iodide is an excellent leaving group, methyl sulfate intermediate, and the dimethylsulfonium moiety in SAM tuned for enzymatic specificity rather than high intrinsic reactivity.[16] Stability varies accordingly; SAM is labile in aqueous solutions and prone to hydrolysis, necessitating biological regeneration systems, while DMS and CH3I are more stable but volatile and corrosive.[17] Methyl group acceptors are typically nucleophilic sites that attack the electrophilic carbon of the donor. Common examples include carboxylates, which form methyl esters upon O-methylation; amines, leading to N-methylated products like tertiary amines or quaternary ammonium salts; thiols, yielding sulfides through S-methylation; and carbon nucleophiles such as enolates, enabling C-methylation at alpha positions of carbonyl compounds.[18] Specificity in donor-acceptor interactions is governed by steric hindrance and electronic effects. Bulky donors like SAM favor less hindered nucleophiles due to its large adenosine moiety, while small, linear CH3I accommodates sterically demanding sites; electronically, hard nucleophiles (e.g., carboxylates) pair better with harder electrophiles like DMS, whereas softer thiols align with CH3I's polarizable iodide leaving group, influencing selectivity in mixed-substrate reactions.[19]| Donor | Relative Reactivity | Primary Applications | Toxicity/Stability Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM) | Low (enzymatic control) | Biological methylations (e.g., DNA, proteins) | Labile in water; non-toxic in vivo |

| Dimethyl sulfate (DMS) | Medium | Industrial O- and N-methylations | Probable carcinogen; corrosive, stable |

| Methyl iodide (CH3I) | High | Laboratory alkylations (broad scope) | Neurotoxin; volatile, stable |

| Tetramethylammonium (TMA) | Low-mild | Selective O-methylation of phenols | Lower toxicity; stable solid |

Methylation in Biology

Methanogenesis

Methanogenesis is an anaerobic process carried out exclusively by methanogenic archaea, wherein carbon dioxide (CO₂) or acetate is reduced to methane (CH₄) through a series of methylation and reduction steps, culminating in the action of methyl-coenzyme M reductase (Mcr). This pathway relies heavily on methylation reactions to form key intermediates, such as methyl-coenzyme M (CH₃-S-CoM), which serves as the direct precursor to methane. In hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, CO₂ is fixed and sequentially reduced via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway to formyl- and then methyl-tetrahydromethanopterin (CH₃-H₄MPT), followed by transfer to coenzyme M. Acetoclastic methanogenesis involves the cleavage of acetate to generate a methyl group that is transferred to coenzyme M, while methylotrophic pathways directly utilize methylated substrates like methanol or methylamines for methyl group incorporation. Overall, the process can be represented by the net equation for CO₂ reduction: with methylation intermediates playing a central role in conserving energy and channeling electrons.[20][21] Central to these pathways are methyltransferases, which catalyze the transfer of methyl groups between cofactors and substrates in methanogenic archaea. The membrane-bound Mtr complex (MtrA-H), a multi-subunit enzyme, is particularly crucial in hydrogenotrophic and methyl-reducing methanogenesis, where it transfers the methyl group from CH₃-H₄MPT to coenzyme M (CoM-SH), forming CH₃-S-CoM while generating a sodium ion gradient for ATP synthesis. In methylotrophic methanogenesis, substrate-specific methyltransferases, such as MtaA (for methanol) or MttA (for trimethylamine), initially transfer methyl groups to corrinoid proteins (e.g., corrinoid/iron-sulfur protein, CFeSP), which then donate the methyl to CoM via activating enzymes. The final step in all pathways involves Mcr, a nickel-containing enzyme that reduces CH₃-S-CoM with coenzyme B (CoB-SH) to release CH₄ and the heterodisulfide CoM-S-S-CoB, which is subsequently reduced to regenerate the thiols. These enzymes ensure efficient methyl handling under strictly anaerobic conditions.[20][21][22] The detailed pathway begins with methyl group formation: in CO₂-reducing methanogenesis, CO₂ is activated by formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase and reduced stepwise to CH₃-H₄MPT via a series of dehydrogenases and reductases, incorporating eight electrons from H₂ or formate. This methyl intermediate is then transferred by the Mtr complex to CoM, forming CH₃-S-CoM. In acetoclastic routes, acetate is activated to acetyl-CoA by the acetyl-CoA synthetase complex, cleaved to CH₃-H₄MPT and CO, with the methyl group routed to CoM. For methylotrophic processes, exogenous methyl donors like methanol (CH₃OH) are oxidized to formaldehyde and then methylated onto H₄MPT or directly transferred via corrinoid-mediated steps. Methane release occurs when Mcr reduces CH₃-S-CoM, with electrons from electron-bifurcating hydrogenases (e.g., Eha or Ehb) driving the overall reduction. These methylation steps not only facilitate carbon flow but also couple catabolism to energy conservation through ion gradients.[20][21] Ecologically, methanogenesis plays a pivotal role in the global carbon cycle by producing methane, a potent greenhouse gas to which methanogenesis contributes the majority (approximately 60%) of total global emissions (as of the 2020s), from both natural sources like wetlands (about 40% of total) and anthropogenic sources such as ruminant guts and landfills.[23][24] Methanogenic archaea thrive in extremophilic anaerobic habitats, including ruminant guts where they convert H₂ and CO₂ from fermentation into CH₄ (accounting for about 30% of anthropogenic emissions), freshwater and marine sediments, and hypersaline environments. In wetlands, methylotrophic methanogens dominate where methylated compounds from decaying organic matter fuel up to 90% of local methane production, influencing atmospheric chemistry and climate feedback loops. This process links anaerobic decomposition to biogeochemical cycling, with methanogens mitigating H₂ accumulation while exacerbating greenhouse effects.[21][22]Metabolic Pathways

One-carbon metabolism encompasses interconnected pathways that facilitate the transfer of single-carbon units for biosynthetic processes, primarily through the folate and methionine cycles, which shuttle methyl groups essential for cellular function. The folate cycle involves the interconversion of tetrahydrofolate (THF) derivatives, starting with the reduction of methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF by methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), providing the methyl donor for methionine regeneration. The methionine cycle, in turn, utilizes S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the primary methyl donor, which is formed from methionine and ATP by methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT); after donating its methyl group, SAM becomes S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), which is hydrolyzed to homocysteine, closing the cycle. These pathways are conserved across eukaryotes and prokaryotes, ensuring efficient methyl group economy for amino acid, nucleotide, and polyamine synthesis.[25][26] Central to the methionine cycle is the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, primarily catalyzed by B12-dependent methionine synthase (MTR). This enzyme transfers a methyl group from 5-methyl-THF to homocysteine, regenerating THF for the folate cycle: MTR is a modular protein with distinct domains: an N-terminal cobalamin-binding region that activates vitamin B12 as methylcobalamin, a central catalytic domain facilitating methyl transfer via redox reactions involving cob(II)alamin intermediates, and a C-terminal domain for homocysteine binding. The mechanism proceeds through oxidative activation of methylcobalamin, followed by nucleophilic attack by homocysteine on the cobalt-methyl bond, with reactivation by methionine synthase reductase to prevent inactivation. An alternative pathway, particularly in liver and kidney, employs betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT), a zinc-dependent enzyme that uses betaine (trimethylglycine) as the methyl donor, converting it to dimethylglycine without requiring folate or B12. BHMT's catalytic mechanism involves zinc coordination to homocysteine's sulfur, polarizing the betaine methylene group for transfer.[27][28][29] Regulation of these pathways maintains metabolic balance, with SAM acting as a key allosteric inhibitor. High SAM levels feedback-inhibit MTHFR, preventing futile cycling and conserving folate, while also inhibiting BHMT to prioritize folate-dependent remethylation under nutrient sufficiency. Nutritional deficiencies disrupt this homeostasis; folate or B12 shortages impair MTR activity, leading to homocysteine accumulation (hyperhomocysteinemia), which is linked to cardiovascular and neurological disorders. For instance, B12 deficiency traps folate as 5-methyl-THF, halting the cycle and exacerbating homocysteine elevation.[30][31][32] Recent advances highlight dysregulation in disease contexts, particularly cancer metabolism. Overexpression of MAT2A, the isoform producing SAM in non-hepatic tissues, supports rapid proliferation by enhancing methyl availability for nucleotide synthesis and epigenetic modifications in tumors like lung and gastric cancers. Studies from the 2020s also underscore dietary influences; for example, diets rich in one-carbon nutrients (e.g., folate, B vitamins) from traditional sources like fermented vegetables improve global methylation status and mitigate metabolic imbalances in at-risk populations.[33][34]Heavy Metal Detoxification

Methylation serves as a key biological mechanism for detoxifying heavy metals by enzymatically adding methyl groups to reduce toxicity, enhance volatility, or facilitate excretion. This process primarily involves S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the methyl donor, transferring methyl groups to metal ions or compounds via specialized methyltransferases. In organisms ranging from microbes to humans, methylation transforms bioavailable inorganic forms into less soluble or more excretable organic species, playing a critical role in mitigating environmental and health risks associated with metals like arsenic and mercury.[35] For arsenic, detoxification occurs through sequential methylation of inorganic arsenite [As(III)] to methylated forms, primarily catalyzed by the enzyme arsenite S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase (ArsM in microbes or AS3MT in humans). This SAM-dependent pathway converts As(III) to monomethylarsonite (MMA(III)), then dimethylarsenite (DMA(III)), and ultimately volatile trimethylarsine (TMA), which dissipates from cells, reducing intracellular accumulation. Pentavalent products like dimethylarsenate (DMA(V)) and trimethylarsine oxide (TMAO) are significantly less toxic—up to 1,000-fold compared to As(III)—as they do not readily bind thiols or disrupt cellular processes. In microbial communities, ArsM homologs are widespread, enabling arsenic volatilization as a survival strategy under oxidative conditions.[35][36][37] Microbial arsenic methylation drives biogeochemical cycling, influencing environmental speciation and human exposure. In anaerobic soils like rice paddies, methylating bacteria outcompete demethylators in younger fields, producing toxic DMA and dimethymonothioarsenate (DMMTA) that accumulate in rice grains, exacerbating contamination in regions like the Americas and Europe. This leads to dietary risks, with methylated arsenic detected in human urine from rice consumption. Recent studies highlight how soil redox and microbial balance govern these dynamics, with high methylator-to-demethylator ratios predicting elevated arsenic in crops and straighthead disease in rice.[37][38][39] Genetic variations in the human AS3MT gene modulate detoxification efficiency, affecting the proportion of methylated metabolites excreted in urine. Rare protein-altering variants, identified in multi-population studies, reduce dimethylarsenic percentage (DMA%) by 6–10%, leading to higher retention of toxic inorganic forms and increased health risks. A 2021 analysis across Bangladeshi, Mexican, and Native American cohorts confirmed these variants' consistent impact, independent of ancestry or exposure levels, underscoring AS3MT's role in personalized arsenic susceptibility.[40] Mercury methylation, predominantly microbial, contrasts by increasing toxicity through biomagnification but serves as a detox strategy in some contexts by converting inorganic Hg(II) to methylmercury (MeHg). The hgcAB gene cluster encodes HgcA (a corrinoid methyltransferase) and HgcB (a ferredoxin), facilitating SAM-dependent transfer of a methyl group to Hg(II), forming the lipophilic MeHg that can volatilize or enter food webs. HgcA's cobalt center and HgcB's iron-sulfur clusters enable electron transfer for methylation, with the process enhanced under anaerobic conditions in sediments and soils. While this reduces Hg(II) toxicity in methylating microbes, MeHg bioaccumulates in aquatic ecosystems, concentrating up to a million-fold in predatory fish.[41][42] Health implications of mercury methylation are severe due to MeHg's neurotoxicity, readily crossing the blood-brain barrier and placenta to cause developmental delays, cognitive deficits, and cardiovascular effects in humans. Environmental factors like dissolved organic matter and sulfate-reducing bacteria amplify methylation rates, linking industrial Hg emissions to global food chain contamination. Recent advances identify over 60 methylating strains, with hgcAB abundance correlating directly to MeHg production in diverse habitats, including rice paddies.[42][43] Cadmium detoxification via methylation is less common than for arsenic or mercury, primarily relying on conjugation with glutathione (GSH) to form excretable complexes rather than direct methylation. GSH chelates Cd(II), enabling vacuolar sequestration or efflux in cells, with SAM indirectly supporting GSH synthesis through metabolic pathways. This mechanism predominates in plants and mammals exposed to Cd, reducing oxidative stress but without the volatility seen in arsenic methylation.[44]Evolutionary Perspectives

Methylation processes trace their origins to the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), where one-carbon metabolism played a central role in carbon assimilation and energy production, with methyl groups essential for pathways like the acetyl-CoA route that fixed CO₂ using H₂ in anaerobic hydrothermal environments approximately 4 billion years ago.[45] In archaea, methanogenesis emerged as an early innovation around 3.5 billion years ago, relying on methylation steps via enzymes such as methyl-coenzyme M reductase to convert methylated substrates into methane, a process that dominated the Archean biosphere.[46][47] SAM synthetases, which generate the universal methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), are highly conserved across all domains of life—bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes—reflecting their presence in LUCA and involvement in at least 10–20 ancient SAM-binding proteins for methylation of nucleic acids and other biomolecules.[48][49] While core metabolic methylation machinery remains broadly conserved, epigenetic components like DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) diverged significantly, with eukaryotes developing specialized DNMT1 for maintenance methylation and DNMT3 for de novo activity, whereas prokaryotes primarily employ them in defense-related restriction-modification systems.[50] These methylation mechanisms conferred adaptive advantages by enhancing metabolic flexibility in nutrient-limited settings, such as the early anoxic Earth, where one-carbon pathways allowed efficient recycling of scarce carbon resources and co-evolved with folate cycles to supply methyl groups for biosynthesis and stress responses.[51] Comparative genomic analyses reveal horizontal gene transfer of methanogenic methyltransferases, such as Mtr and Hmd genes, among archaeal lineages like Euryarchaeota and TACK superphylum, facilitating the spread of methanogenesis beyond its ancestral host.[52] Fossil biomarkers, including biologically derived methane inclusions from 3.4–3.5 billion-year-old rocks, corroborate these ancient origins, while 2020s phylogenomic studies document dynamic evolution of methylation enzymes, including independent losses of DNMTs in lineages like Ecdysozoa, highlighting ongoing adaptations across life's domains.[47][53]Epigenetic Methylation

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation refers to the covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine residues in DNA, predominantly at CpG dinucleotides, resulting in 5-methylcytosine (5mC). This modification serves as a key epigenetic mechanism that influences gene expression, chromatin structure, and genomic stability without changing the underlying nucleotide sequence. In vertebrates, DNA methylation patterns are dynamically established and maintained during development, contributing to cellular differentiation and tissue-specific gene regulation. Aberrant methylation is implicated in various diseases, particularly cancer, where it can lead to inappropriate gene silencing or activation. The primary mechanism of DNA methylation involves DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which transfer a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor, to cytosine. Maintenance methylation is primarily catalyzed by DNMT1, which recognizes hemimethylated DNA after replication and methylates the newly synthesized strand to preserve existing patterns. De novo methylation, establishing new patterns, is mediated by DNMT3A and DNMT3B, often in complex with their regulatory subunit DNMT3L. The enzymatic reaction can be represented as: where SAH is S-adenosylhomocysteine. This process typically occurs at CpG sites, though non-CpG methylation is prevalent in specific contexts, such as CHG and CHH motifs in plants for transposon silencing and gene body methylation in mammalian neurons. Biologically, DNA methylation facilitates gene silencing by recruiting methyl-binding proteins like MeCP2, which in turn associate with histone deacetylases and other repressors to compact chromatin. It plays essential roles in genomic imprinting, where parent-of-origin-specific methylation marks at imprinting control regions (ICRs) silence one allele, ensuring monoallelic expression of genes like IGF2 and H19. In X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), methylation spreads across the inactive X chromosome in female mammals, maintaining dosage compensation by silencing most X-linked genes through promoter hypermethylation following Xist RNA coating. During embryonic development, global demethylation occurs in the zygote and inner cell mass, followed by waves of de novo methylation to establish tissue-specific patterns. Detection of DNA methylation relies on methods that distinguish 5mC from unmethylated cytosine. Bisulfite sequencing, the gold standard, treats DNA with sodium bisulfite, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines during sequencing) while leaving 5mC intact, allowing site-specific resolution at single-base level. Genome-wide approaches include methylation arrays, such as Illumina's Infinium platforms, which interrogate hundreds of thousands of CpG sites via hybridization probes. These techniques have revealed dynamic methylation landscapes, including active demethylation via ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, discovered in 2009, which oxidize 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), facilitating base excision repair and erasure of methylation marks. In cancer, aberrant hypermethylation of CpG islands in tumor suppressor gene promoters, such as p16INK4a and MLH1, leads to their transcriptional silencing, promoting oncogenesis by disabling cell cycle control and DNA repair. This epigenetic alteration is observed in up to 80% of solid tumors and leukemias, often cooperating with genetic mutations. Therapeutic strategies target these aberrations with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors like azacitidine, a cytidine analog incorporated into RNA and DNA, where it covalently traps DNMTs during methylation attempts, depleting enzyme levels and inducing global hypomethylation to reactivate silenced genes. Azacitidine is FDA-approved for myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia, with response rates around 50% in clinical trials. Recent advances highlight non-CpG methylation's role in the brain, where it accumulates in neuronal gene bodies during postnatal development, influencing synaptic plasticity and binding to MeCP2 for repression, and in plants, where it constitutes over 30% of total methylation for heterochromatin maintenance.RNA Methylation

RNA methylation refers to the addition of methyl groups to RNA molecules, a key epitranscriptomic modification that dynamically regulates RNA processing, stability, and function without altering the genetic code. The most prevalent form is N6-methyladenosine (m6A), primarily occurring on messenger RNA (mRNA) in eukaryotic cells, where it influences gene expression at multiple levels. Other notable modifications include 5-methylcytosine (m5C) on transfer RNA (tRNA), which supports tRNA stability and translation accuracy. These modifications are reversible and orchestrated by a machinery of enzymes that install, remove, and interpret them, paralleling epigenetic mechanisms in DNA but with greater dynamism suited to RNA's transient nature.[54][55] The core mechanism of RNA methylation involves the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor, to specific nucleotide residues via SAM-dependent methyltransferases. For m6A, this occurs at the nitrogen-6 position of adenosine, typically in the consensus sequence RRACH (R = purine, A = adenosine, C = cytosine, H = A/C/U), often near stop codons or 3' untranslated regions of mRNA. m6A was first identified in the 1970s as an abundant modification in eukaryotic mRNA, but the full enzymatic machinery was elucidated in the 2010s, marking the rise of epitranscriptomics. Writers, such as the METTL3-METTL14-WTAP core complex, catalyze m6A installation in the nucleus, while erasers like fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) remove it in a demethylation reaction dependent on α-ketoglutarate and iron. Readers, including YTH domain-containing proteins (e.g., YTHDF1/2/3 and YTHDC1/2), bind m6A-modified RNA to mediate downstream effects, such as nuclear export or decay. Similarly, m5C on tRNA is installed by NOP2/Sun domain family member 2 (NSUN2) and recognized by readers like ALYREF to facilitate mRNA export.[56][57][58] Functionally, m6A promotes mRNA decay by recruiting YTHDF2 to target transcripts for deadenylation and degradation, thereby fine-tuning gene expression; it also enhances translation efficiency via YTHDF1 recruitment to the mRNA cap and influences alternative splicing through interactions with splicing factors like SRSF3. In tRNA, m5C stabilizes the molecule against endonucleolytic cleavage and ensures precise codon recognition during protein synthesis. These roles extend to viral RNAs, where host m6A machinery can methylate SARS-CoV-2 transcripts to restrict replication, but viral proteins sometimes evade or hijack this for immune escape. Recent 2020s research has expanded to circular RNAs (circRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), revealing m6A and m5C modifications that regulate circRNA stability in neuronal differentiation and lncRNA-mediated chromatin interactions in cancer, fueling the epitranscriptomics boom with advanced mapping techniques like m6A-seq.[54][59][60] Dysregulation of RNA methylation links to diseases, with FTO variants associated with altered m6A levels contributing to obesity through hypothalamic regulation of appetite genes like ghrelin. In cancer, upregulated METTL3 drives oncogenic mRNA stabilization, while ALKBH5 loss promotes tumor growth; thus, m6A inhibitors targeting writers or erasers show therapeutic promise, such as METTL3 small-molecule blockers enhancing chemotherapy sensitivity in leukemia models. Ongoing studies highlight potential in targeting lncRNA m6A for precision oncology, underscoring RNA methylation's role in disease etiology and intervention.[61][62][63]Protein Methylation

Protein methylation refers to the covalent addition of one or more methyl groups to specific amino acid residues, primarily lysine and arginine, within proteins, serving as a key post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular processes. This modification occurs on both histone and non-histone proteins, with lysine residues capable of mono-, di-, or tri-methylation and arginine residues typically undergoing mono- or di-methylation in asymmetric or symmetric forms. The primary enzymes catalyzing arginine methylation are the protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs), a family of nine enzymes divided into types I (producing asymmetric di-methylarginine, e.g., PRMT1), type II (symmetric di-methylarginine, e.g., PRMT5), and type III (monomethylarginine, e.g., PRMT7). Lysine methylation is predominantly mediated by SET-domain-containing methyltransferases, including families like SET1/COMPASS for H3K4, SUV39 for H3K9, and EZ for H3K27, which exhibit varying degrees of processivity depending on the substrate and cellular context.[64] In histones, methylation patterns form part of the "histone code," where specific marks dictate chromatin structure and transcriptional outcomes by serving as docking sites for reader proteins. Trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is a hallmark of active promoters, facilitating recruitment of chromatin remodelers like the SWI/SNF complex and promoting gene activation. In contrast, trimethylation of H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), deposited by the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), correlates with transcriptional repression and heterochromatin maintenance, often at developmental genes. These opposing marks enable bivalent chromatin states, balancing activation and repression during cell differentiation. Non-histone targets extend this regulatory layer; for example, SET7/9 methylates p53 at lysine 372 to stabilize it and enhance DNA damage-induced transcription, while methylation of DNMT1 at lysine 142 by SET7/9 promotes its degradation, linking protein methylation to epigenetic maintenance.[65] The biochemical mechanism of protein methylation is strictly dependent on S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), where the enzyme's active site positions the substrate residue to accept the methyl group from SAM, yielding S-adenosylhomocysteine as a byproduct and enabling precise control over modification extent. Reversibility is achieved through demethylation: lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), a flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent amine oxidase, removes mono- and di-methyl groups from lysine via oxidative deamination, generating formaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide. The jumonji C (JmjC)-domain-containing (JMJD) family, comprising over 30 members, employs a 2-oxoglutarate and Fe(II)-dependent hydroxylation mechanism to demethylate mono-, di-, or tri-methyl lysines across a broader substrate range, including H3K27me3 via JMJD3. These pathways ensure dynamic turnover of methyl marks in response to cellular signals.[66][67] Functionally, protein methylation orchestrates chromatin remodeling by modulating nucleosome positioning and accessibility—H3K4me3, for instance, recruits ATP-dependent remodelers to open chromatin for transcription—while in non-histone contexts, it fine-tunes signal transduction pathways, such as PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation of transcription factors altering their localization and activity. Dysregulation of these processes contributes to neurodegeneration; hypomethylation of tau at arginine residues, driven by reduced PRMT activity, promotes tau hyperphosphorylation, aggregation, and neurofibrillary tangle formation in Alzheimer's disease models. Recent insights from the 2020s reveal non-histone methylation's role in immunity, where PRMT1 methylates heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 to regulate inflammatory cytokine splicing and anti-inflammatory responses in macrophages. Additionally, lysine methylation influences liquid-liquid phase-separated condensates, as seen in SET7/9-modified proteins that modulate condensate assembly for efficient signal transduction in immune and stress responses.[68][69][70][71]Methylation in Chemistry

Electrophilic Methylation

Electrophilic methylation refers to a class of reactions in organic synthesis where a methyl cation equivalent (CH₃⁺) is transferred from an electrophilic donor to a nucleophilic substrate, most commonly involving oxygen or nitrogen atoms as the nucleophilic sites.[72] This process is fundamental for introducing methyl groups in ethers, esters, and amines, enabling the modification of functional groups under controlled conditions.[72] The electrophilic nature of the methyl donor ensures regioselective attack at electron-rich centers, distinguishing it from other alkylation strategies.[73] Common reagents for electrophilic methylation include methyl halides such as iodomethane (CH₃I) and bromomethane (CH₃Br), which act as direct sources of the methyl electrophile.[72] Iodomethane exhibits the highest reactivity among these due to the excellent leaving group ability of iodide, following the order CH₃I > CH₃Br > CH₃Cl, while chloromethane and fluoromethane are far less effective.[73] Diazomethane (CH₂N₂) serves as another key reagent, generating the methyl electrophile through loss of nitrogen, particularly suited for sensitive substrates.[74] Dimethyl sulfate ((CH₃)₂SO₄) is also widely employed, offering high reactivity for O- and N-methylations via sequential transfer of its two methyl groups.[75] Side reactions, such as over-methylation in polyfunctional molecules or competing alkylation pathways with longer-chain halides, can occur, necessitating careful control of stoichiometry and reaction conditions.[72] In applications, electrophilic methylation is prominently used for the esterification of carboxylic acids, exemplified by the reaction with diazomethane, which proceeds under mild, neutral conditions without requiring additional catalysts beyond trace methanol.[74] This method is highly efficient for labile compounds, yielding methyl esters in high purity.[76] For O-methylation, phenols are converted to anisole derivatives using iodomethane in the presence of a base like potassium carbonate, while N-methylation of amines employs similar conditions to form tertiary amines selectively.[73] Dimethyl sulfate finds utility in industrial-scale etherifications, such as in the synthesis of vanillin derivatives.[75] These methods offer advantages in versatility and compatibility with acid-sensitive substrates, enabling clean transformations at room temperature.[72] However, limitations include poor selectivity in multifunctional systems and the inherent hazards of the reagents: diazomethane is explosive and highly toxic, requiring specialized handling, while dimethyl sulfate is carcinogenic and corrosive.[74] Methyl halides, though less hazardous, pose risks of volatility and lachrymatory effects, prompting the development of safer alternatives in modern synthesis.[73]Nucleophilic Methylation

Nucleophilic methylation refers to reactions in which a methyl carbanion or its synthetic equivalent serves as a nucleophile, attacking electrophilic centers to form new carbon-carbon bonds, most commonly in C-methylation processes. This approach is fundamental in organic synthesis for introducing methyl groups at carbonyl carbons or other electrophiles like alkyl halides.[78][8] Key reagents for generating the methyl nucleophile include organometallic species such as the methyl Grignard reagent (CH₃MgBr), prepared by reacting methyl bromide with magnesium in diethyl ether or THF, and methyllithium (CH₃Li), obtained from methyl iodide and lithium metal in hexane or pentane. These compounds exhibit strong nucleophilicity due to the polarized carbon-metal bond, where the methyl group behaves as R⁻. Umpolung strategies, such as those employing 1,3-dithiane anions, provide masked nucleophilic equivalents that can facilitate selective methylation by inverting the reactivity of typically electrophilic carbonyls, allowing addition to alkyl halides or other electrophiles in a controlled manner.[79][78][80] A primary application is the addition to aldehydes for synthesizing secondary alcohols, which can serve as precursors to ketones upon oxidation. The reaction proceeds via nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon, forming an alkoxide intermediate that yields the alcohol upon aqueous hydrolysis: This method is widely used for constructing complex carbon frameworks in natural product synthesis, with the methyl group providing essential steric and electronic modulation. Similar additions occur with ketones to afford tertiary alcohols, though selectivity is key to prevent side reactions.[79][78] Challenges in nucleophilic methylation include over-addition, particularly with reactive substrates like esters, where multiple equivalents of the reagent lead to tertiary alcohols instead of the desired ketones, necessitating careful stoichiometry and workup conditions. Additionally, the strong basicity of these reagents (pKa ≈ 40–50) can cause enolization or deprotonation of alpha-hydrogens in carbonyls, reducing yields, while achieving stereoselectivity in creating new chiral centers remains difficult with achiral reagents due to rapid background reactions. Modern variants address these issues through chiral additives or catalytic systems, such as nickel- or rhodium-catalyzed processes using trimethylaluminum, and emerging organocatalytic methods that enhance enantioselectivity without stoichiometric metals.[79][78][81]Specific Synthetic Methods

The Eschweiler-Clarke reaction represents a classic method for the reductive N-methylation of primary and secondary amines to tertiary amines, employing formaldehyde as the methyl source and formic acid as both the reducing agent and catalyst. This procedure typically involves heating the amine with excess formaldehyde and formic acid, often in a solvent like water or ethanol, yielding the dimethylated product along with carbon dioxide and water as byproducts. The balanced equation for the dimethylation of a primary amine is: This method is particularly effective for aliphatic and aromatic amines, offering high yields (often >90%) under mild conditions without requiring additional catalysts, though it is limited by the potential over-methylation of sensitive substrates.[82] Diazomethane (CH₂N₂) serves as a versatile reagent for O-methylation of carboxylic acids to form methyl esters, as well as in the Arndt-Eistert synthesis for homologation of carboxylic acids via diazoketone intermediates. The reaction with carboxylic acids proceeds rapidly at room temperature in ether solvents, generating the ester and nitrogen gas, but diazomethane's toxicity, carcinogenicity, and explosive nature necessitate stringent safety protocols. Safer alternatives, such as trimethylsilyldiazomethane (TMSCHN₂), have been developed, which react similarly with carboxylic acids in the presence of methanol or trimethylsilyl chloride to afford methyl esters with comparable efficiency and reduced hazards; for instance, TMSCHN₂ enables the Arndt-Eistert synthesis under milder conditions, achieving yields up to 85% for diazoketone formation.[83][84] Other selective methods include the use of borane-dimethylamine complex (BH₃·NHMe₂) for N-methylation, particularly in copper-hydride catalyzed processes where it acts as a reducing agent alongside formaldehyde or CO₂-derived sources to achieve mono- or dimethylation of aromatic amines with high selectivity (e.g., >95% for N-methylaniline from aniline). Phase-transfer catalysis facilitates efficient alkylations, including methylation, by enabling the transfer of anionic species like methyl sulfate or iodide across immiscible phases; for example, quaternary ammonium salts catalyze the N-methylation of lysergic acid derivatives in biphasic systems (dichloromethane/water) using dimethyl sulfate, yielding pharmaceutical intermediates with improved reaction rates and reduced solvent use compared to homogeneous conditions.[85][86] On an industrial scale, methylation is integral to pharmaceutical production, such as the N-methylation of intermediates in the synthesis of ergot alkaloids like those derived from lysergic acid, where phase-transfer or reductive methods ensure scalability and purity. Green chemistry alternatives emphasize enzymatic methylation using S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferases, which selectively methylate alkaloids or phenolic substrates under aqueous, ambient conditions; for instance, co-immobilized methyltransferases achieve regioselective O- or N-methylation of high-value compounds like thebaine with >90% conversion, minimizing waste and avoiding toxic reagents.[86][87] Post-2010 advancements include photocatalyzed methods, where visible-light-driven processes using iridium or organic dyes enable direct C-H methylation with methanol as the C1 source; these approaches, such as GaN-semiconductor-mediated sp³/sp² C-H methylations, proceed at room temperature with high site-selectivity (e.g., 80-95% yields for aryl C-H bonds). Metal-free strategies have also gained traction, exemplified by the N-methylation of sulfoximines or amines using CO₂ and silanes under organocatalytic conditions, offering sustainable alternatives with atom economies >90% and broad substrate tolerance.[88][89] Recent developments as of 2025 include transition metal-catalyzed N-methylation using methanol as a sustainable methyl source, enabling efficient transformations of nitrogen-containing molecules with minimal waste. Additionally, CO₂-promoted reductive methylation systems have advanced for selective carbon-heteroatom bond formation, overcoming challenges in side reactions and scalability for industrial applications.[90][91]Applications and Implications

In Medicine and Biotechnology

Methylation plays a pivotal role in medical and biotechnological applications, particularly through epigenetic modifications that influence gene expression in disease states and therapeutic interventions. In oncology, DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors such as decitabine have been approved for treating myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) by reactivating silenced tumor suppressor genes via hypomethylation.[92] Decitabine incorporates into DNA, trapping DNMTs and leading to their degradation, which results in global DNA demethylation and improved survival outcomes in elderly AML patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy.[93] Combination therapies pairing DNMT inhibitors with histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, such as vorinostat, enhance antitumor effects by synergistically reversing epigenetic silencing, promoting apoptosis, and reducing tumor stem cell populations in various cancers including AML and solid tumors.[94][95] Metabolic pathways involving methylation are targeted to address disorders linked to one-carbon metabolism disruptions. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) analogs serve as tools to modulate methyltransferase activity and restore methylation balance in conditions like hyperhomocysteinemia, where elevated homocysteine impairs the SAM/SAH ratio and contributes to vascular damage; supplementation strategies aim to replenish SAM levels and mitigate oxidative stress.[96][97] Folate supplementation, which supports SAM synthesis via the methionine cycle, reduces the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) by 50-70% during embryogenesis, with higher doses (4 mg) preventing over 70% of recurrent NTDs; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends 400–800 μg daily for women capable of pregnancy.[98][99] DNA methylation patterns serve as robust biomarkers for aging and cancer prognosis. The Horvath epigenetic clock, based on methylation levels at 353 CpG sites across tissues, accurately predicts chronological age and biological aging, with accelerated clock rates associating with age-related diseases and mortality risk.[100][101] In precision oncology, N6-methyladenosine (m⁶A) RNA profiling identifies dysregulated methylation regulators like METTL3, which promote tumor progression; high m⁶A levels correlate with poor survival in cancers such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, enabling personalized treatment stratification.[102][103] Biotechnological advancements leverage engineered systems for precise methylation control. CRISPR-based tools, including dCas9 fused to DNMT3A, enable targeted DNA hypermethylation at specific loci, suppressing gene expression in models of Alzheimer's disease and cancer without altering the underlying sequence; these systems demonstrate heritability over multiple cell divisions in human hematopoietic cells.[104][105] Engineered methyltransferases, such as those derived from bacterial or plant sources, facilitate synthetic biology applications like de novo biosynthesis of methylated flavonoids and antibiotics, improving pathway efficiency in microbial hosts for pharmaceutical production.[106][107] Recent 2020s developments highlight methylation's integration into immunotherapy and vaccine design. N1-methylpseudouridine (m¹Ψ) modifications in mRNA vaccines enhance stability and translation, as seen in COVID-19 platforms, and similar strategies are being adapted for cancer vaccines to boost neoantigen presentation and T-cell responses.[108] DNA methylation regulates PD-1 expression on T cells, with hypomethylation in the PD-1 promoter correlating with immunotherapy resistance; epigenetic modifiers targeting these sites, such as DNMT inhibitors, sensitize tumors to anti-PD-1 blockade by restoring immune checkpoint dynamics.[109][110]In Environmental Science

In environmental science, methylation plays a pivotal role in biogeochemical cycles, particularly for toxic metals like mercury and arsenic, where microbial processes transform inorganic forms into organic compounds that alter their mobility and bioavailability. Anaerobic bacteria, such as Geobacter bemidjiensis, methylate inorganic mercury (Hg(II)) to methylmercury (MeHg) under anoxic conditions in sediments and wetlands, with production rates reaching up to 5% of added Hg(II) within hours, contributing to the global mercury cycle.[111] Similarly, in arsenic-contaminated soils like paddy fields, microbes such as the novel Cytophagaceae species SM-1 efficiently methylate arsenite to volatile trimethylarsine (TMAs), converting nearly all added arsenic (10 μM) to methylated forms within 24 hours, facilitating arsenic volatilization and reducing soil retention.[112] These transformations, driven by genes like hgcAB for mercury and arsM for arsenic, influence elemental cycling in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, often enhancing pollutant dispersal.[113] Methylation significantly affects the fate of environmental pollutants by increasing the mobility of metals, which can compromise water quality. For instance, the production of volatile arsines like trimethylarsine from soils enhances arsenic transport into the atmosphere, with field fluxes showing emissions up to several ng/m²/h, potentially contaminating groundwater and surface waters in agricultural areas. Methylmercury, being lipophilic and persistent, similarly elevates risks in aquatic systems, where it partitions into sediments but can remobilize under changing redox conditions, leading to broader distribution and elevated concentrations in runoff-prone watersheds.[111] These processes underscore methylation's dual role: while volatilization may detoxify soils by removing metals as gases, it can inadvertently spread contaminants, exacerbating water quality issues in regions with high metal inputs from mining or industry. Microbial methylation contributes to broader environmental dynamics, including climate regulation through methanogenesis and potential bioremediation applications. Methyl-based methanogenesis, performed by archaea like Methanosarcina and Methanolobus using substrates such as methanol and trimethylamine, contributes significantly (up to 30-40% globally) to biogenic methane emissions—a potent greenhouse gas responsible for about 0.5°C of observed global warming since pre-industrial times—particularly from anoxic marine sediments and wetlands.[114] In bioremediation, methylating microbes like Pseudomonas and Bacillus species volatilize heavy metals (e.g., Hg, As, Se) into gaseous forms, offering a strategy to reduce soil contamination by converting non-volatile ions to removable methyl derivatives, though efficacy depends on site-specific conditions like pH and oxygen levels.[115] Methylation links environmental processes to human impacts via bioaccumulation and international policy responses. Methylmercury bioaccumulates in aquatic food webs, concentrating up to 1 million times higher in predatory fish like tuna compared to surrounding water, posing neurotoxic risks to ecosystems and human consumers through fish ingestion.[116] This has prompted global action, such as the Minamata Convention on Mercury (2013), which aims to reduce anthropogenic mercury releases—including those leading to methylation—through controls on mining, emissions, and waste, with over 140 parties committing to protect aquatic environments and food chains.[117] Recent studies from the 2020s highlight emerging feedbacks, particularly how microplastics influence methylation in polluted soils. Microplastic plastispheres in paddy soils act as hotspots for MeHg production, with distinct microbial communities (e.g., enriched Geobacterales) increasing methylation potential by up to twofold compared to bulk soil, potentially amplifying mercury risks under climate-driven plastic accumulation.[118] Similarly, conventional and biodegradable microplastics alter arsenic methylation pathways via chemical sorption and microbial shifts, enhancing volatile arsenic emissions and linking plastic pollution to metal cycling feedbacks in warming, flooded agroecosystems.[119]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/232238517_Green_chemistry_metrics_A_comparative_evaluation_of_dimethyl_carbonate_methyl_iodide_dimethyl_sulfate_and_methanol_as_methylating_agents

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {RCO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {H} {}+{}\mathrm {tmsCHN} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}+{}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {OH} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}\mathrm {RCO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}{}+{}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {Otms} {}+{}\mathrm {N} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/99e6a069dc908747dac07cd0714c61760f4b816a)