Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Niue[c] is a self-governing island country in free association with New Zealand. It is situated in the South Pacific Ocean and is part of Polynesia, and predominantly inhabited by Polynesians. One of the world's largest coral islands, Niue is commonly referred to as "The Rock", which comes from the traditional name "Rock of Polynesia".[11]

Key Information

Niue's position is inside a triangle drawn between Tonga, Samoa, and the Cook Islands. It is 2,400 kilometres (1,500 mi) northeast of New Zealand, and 604 kilometres (375 mi) northeast of Tonga. Niue's land area is about 261.46 square kilometres (100.95 sq mi) and its population was 1,689 at the Census in 2022.

The terrain of the island has two noticeable levels. The higher level is made up of a limestone cliff running along the coast, with a plateau in the centre of the island reaching approximately 60 metres (200 ft) above sea level. The lower level is a coastal terrace approximately 0.5 km (0.3 miles) wide and about 25–27 metres (80–90 feet) high, which slopes down and meets the sea in small cliffs. A coral reef surrounds the island; the only major break in the reef is in the central western coast, close to the capital, Alofi.

Niue is subdivided into 14 villages (municipalities). Each village has a council that elects its chairperson; they are also electoral districts, and send an assemblyperson to the Niue Assembly (parliament).[12]

Since Niue is part of the Realm of New Zealand, most diplomatic relations on behalf of Niue are conducted by New Zealand. Niueans are citizens of New Zealand, and Charles III is Niue's head of state in his capacity as King of New Zealand. Between 90% and 95% of Niuean people live in New Zealand,[13] along with about 70% of the speakers of the Niuean language.[14] Niue is a bilingual country: 30% of the population speak both Niuean and English; 11% speak only English; and 46% speak only Niuean.

Niue is a parliamentary democracy; legislative elections are held every three years. Niue is not a member of the United Nations (UN); however, UN organisations accept its status as a freely associated state, equivalent to an independent state for the purposes of international law.[3] As such, Niue is a member of some UN specialised agencies (such as UNESCO and the WHO),[15] and is invited, along with the other non-UN member state, the Cook Islands, to attend United Nations conferences open to "all states". Niue has been a member of the Pacific Community since 1980.

History

[edit]Polynesians from Samoa settled Niue around 900 CE. Further settlers arrived from Tonga in the 16th century.[16]

Until the beginning of the 18th century, Niue appears to have had no national government or national leader; chiefs and heads of families exercised authority over segments of the population. A succession of patu-iki (kings) ruled, beginning with Puni-mata. Tui-toga, who reigned from 1875 to 1887, was the first of the country's kings to adopt Christianity.[17]

The first Europeans to sight Niue sailed under Captain James Cook in 1774. Cook made three attempts to land, but the inhabitants refused to grant permission to do so. He named the island "Savage Island" because, as legend has it, the natives who "greeted" him were painted in what appeared to be blood. The substance on their teeth was hulahula, a native red fe'i banana.[18] For the next couple of centuries, Niue was known as "Savage Island" until its original name, "Niue", which translates as "behold the coconut",[19] regained use.

Whaling vessels were some of the most regular visitors to the island in the nineteenth century. The first on record was the Fanny in February 1824. The last known whaler to visit was the Albatross in November 1899.[20]

Religious colonialism

[edit]The next documented European visitors represented the London Missionary Society, who arrived on the Messenger of Peace. After many years of trying to land a European missionary, they abducted a Niuean named Nukai Peniamina and trained him as a pastor at the Malua Theological College in Samoa.[21]

Peniamina returned in 1846 on the John Williams as a missionary with the help of Toimata Fakafitifonua. He was finally allowed to land in Uluvehi Mutalau after a number of attempts in other villages had failed. The chiefs of Mutalau village allowed him to land and protected him day and night at the fort in Fupiu.[22]

Christianity was first taught to the Mutalau people before it spread to all the villages. Originally other major villages opposed the introduction of Christianity and had sought to kill Peniamina.[citation needed] The people from the village of Hakupu, although the last village to receive Christianity, came and asked for a "word of God"; hence, their village was renamed "Ha Kupu Atua" meaning "any word of God", or "Hakupu" for short.[citation needed]

In July 1849, Captain John Erskine visited the island in HMS Havannah.[23]

Request for colony status

[edit]

In 1889, the chiefs and rulers of Niue, in a letter to Queen Victoria, asked her "to stretch out towards us your mighty hand, that Niue may hide herself in it and be safe".[24] After expressing anxiety lest some other nation should take possession of the island, the letter continued: "We leave it with you to do as seems best to you. If you send the flag of Britain that is well; or if you send a Commissioner to reside among us, that will be well".[24] The British did not initially take up the offer. In 1900 a petition by the Cook Islanders asking for annexation included Niue "if possible".[24]

In a document dated 19 October 1900, the King and Chiefs of Niue consented to "Queen Victoria taking possession of this island". A despatch to the Secretary of State for the Colonies from the Governor of New Zealand referred to the views expressed by the Chiefs in favour of "annexation" and to this document as "the deed of cession". A British Protectorate was declared, but it remained short-lived. Niue was brought within the boundaries of New Zealand on 11 June 1901 by the same Order and Proclamation as the Cook Islands. The Order limited the islands to which it related by reference to an area in the Pacific described by co-ordinates, and Niue, at 19.02 S., 169.55 W, lies within that area.[24]

Modern period

[edit]

Niue International Airport was established in 1970 and opened to commercial flight passengers in November 1971.[25][26]

The New Zealand Parliament restored self-government in Niue with the 1974 Niue Constitution Act, following the 1974 Niuean constitutional referendum in which Niueans had three options: independence, self-government, or continuation as a New Zealand territory. The majority selected self-government, and Niue's written constitution[27] was promulgated as supreme law.[citation needed] Robert Rex was elected by the Niue Assembly as the first Premier of Niue in 1974, a position he held until his death 18 years later.[28][29] In 1984, Rex became the first Niuean to receive a knighthood.[30]

In January 2004, Cyclone Heta hit Niue, killing one person and causing extensive damage to the entire island, including wiping out most of the south of the capital, Alofi.[31]

On 7 March 2020, the International Dark-Sky Association announced that Niue had become the first entire country to be designated an International Dark Sky Sanctuary.[32] On 29 September 2022, President Joe Biden announced that the United States would recognise Niue as a sovereign nation.[33] On 25 September 2023, recognition was declared by President Biden and diplomatic relations were established.[34]

Geography

[edit]

Niue is a 261.46 km2 (100.95 sq mi) raised coral atoll in the southern Pacific Ocean, east of Tonga.[35] There are three outlying coral reefs within the exclusive economic zone, with no land area:

- Beveridge Reef, 240 km (150 mi) southeast, submerged atoll drying during low tide, 9.5 km (5.9 mi) north-south, 7.5 km (4.7 mi) East-West, total area 56 km2 (22 sq mi), no land area, lagoon 11 metres (36 ft) deep.

- Antiope Reef, 180 km (110 mi) northeast, a circular plateau approximately 400 metres (1,300 ft) in diameter, with a least depth of 9.5 metres (31 ft).

- Haran Reef (also known as Harans Reef), 294 km (183 mi) southeast.

Besides these, Albert Meyer Reef (almost 5 km (3.1 mi) long and wide, least depth 3 m (9.8 ft), 326 km (203 mi) southwest) is not officially claimed by Niue; further, the existence of Haymet Rocks (1,273 km (791 mi) east-southeast) is in doubt.

Niue is one of the world's largest coral islands. The terrain consists of steep limestone cliffs along the coast with a central plateau rising to about 60 metres (200 ft) above sea level. A coral reef surrounds the island, with the only major break in the reef being in the central western coast, close to the capital, Alofi. A number of limestone caves occur near the coast.

The island is roughly oval in shape (with a diameter of about 18 kilometres (11 mi), with two large bays indenting the western coast, Alofi Bay in the centre and Avatele Bay in the south. Between these is the promontory of Halagigie Point. A small peninsula, TePā Point (Blowhole Point), is close to the settlement of Avatele in the southwest. Most of the population resides close to the west coast, around the capital, and in the northwest.

Geology

[edit]

Some Niue soils are geochemically very unusual. They are extremely weathered tropical soils, with high levels of iron and aluminium oxides (oxisol) and mercury, and they contain high levels of natural radioactivity, with Thorium-230 and Protactinium-231 heading the decay chains. This distribution of elements is found naturally on very deep seabeds, but the geochemical evidence suggests that the origin of these elements is extreme weathering of coral and brief sea submergence 120,000 years ago. Endothermal upwelling, by which mild volcanic heat draws deep seawater up through the porous coral, almost certainly contributes.[36]

No adverse health effects from the radioactivity or the other trace elements have been demonstrated, and calculations show that the level of radioactivity is probably much too low to be detected in the population. These unusual soils are very rich in phosphate, but it is not accessible to plants, being in the very insoluble form of iron phosphate, or crandallite. It is thought that similar radioactive soils may exist on Lifou and Mare near New Caledonia, and Rennell in the Solomon Islands, but no other locations are known.

Climate

[edit]The island has a tropical rainforest climate (Af) according to the Köppen climate classification with high temperatures and rainfall throughout the year.[citation needed] The wet season runs from November to April, and the dry season runs from May to October.[37]

| Climate data for Alofi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 38 (100) |

38 (100) |

32 (90) |

36 (97) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

35 (95) |

37 (99) |

36 (97) |

31 (88) |

37 (99) |

36 (97) |

38 (100) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28 (82) |

29 (84) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26 (79) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23 (73) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

15 (59) |

13 (55) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

15 (59) |

15 (59) |

11 (52) |

17 (63) |

9 (48) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 261.6 (10.30) |

253.6 (9.98) |

305.6 (12.03) |

202.6 (7.98) |

138.2 (5.44) |

88.9 (3.50) |

96.4 (3.80) |

105.8 (4.17) |

102.4 (4.03) |

123.8 (4.87) |

145.5 (5.73) |

196.2 (7.72) |

2,018.4 (79.46) |

| Source: Weatherbase[38] | |||||||||||||

Environment

[edit]

Niue is attempting to pursue a policy of "green growth". The Niue Island Organic Farmers Association is currently paving way to a Multilateral Environmental Agreement (MEA) committed to making Niue the world's first fully organic nation by 2020.[39][40][41]

As of 2012, Niue had one of the highest rates of greenhouse gas emissions per capita in the world,[42] due to the small population of the country.[43][44] Niue aimed to use 80% renewable energy by 2025.[45][46][47] In July 2025, the target was shifted to early 2026.[48]

In July 2009, a solar panel system was installed, injecting about 50 kW into the Niue national power grid. This is nominally 6% of the average 833 kW electricity production. The solar panels are at Niue High School (20 kW), Niue Power Corporation office, (1.7 kW)[49] and the Niue Foou Hospital (30 kW). The EU-funded grid-connected photovoltaic systems are supplied under the REP-5 programme and were installed recently by the Niue Power Corporation on the roofs of the high school and the power station office and on ground-mounted support structures in front of the hospital. They will be monitored and maintained by the NPC.[50]

In 2014, two additional solar power installations were added to the Niue national power grid. One was funded under PALM5 of Japan and is located outside the Tuila power station; so far, only this has battery storage. The second power station is under European Union funding; it is located opposite the Niue International Airport Terminal.

In 2023, the governments of Niue and other island states at risk from climate change (Fiji, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Tonga and Vanuatu) launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific", calling for the phasing out of fossil fuels; a "rapid and just transition" to renewable energy; and a strengthening of environmental law, including introducing the crime of ecocide.[51][52][53]

In 2022, Niue declared its entire EEZ to be a marine park, though enforcement of that declaration would be a challenge. The entire Fisheries Division was reported to have only five staff and there were no locally based patrol boats. Enforcement would depend on stronger support from the New Zealand Defence Forces, though its ability to maintain a continuous presence was limited.[54]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Niue is part of the Tongan tropical moist forests terrestrial ecoregion.[55] The island is home to approximately 60 native or pre-European plants, and approximately 160 naturalised flowering plant species.[56] Compared to other Polynesian islands, Niue has sparse documentation for what plants were traditionally found on the island (almost no records are found between the documentation by James Cook's crew in 1774, and Truman G. Yuncker's botanical survey of the island in 1940).[56]

The Huvalu Forest Conservation Area is a 5,400 hectare (20 sq. mi.) site on the eastern side of the island. It was established in 1992 and protects the largest area of primary forest in Niue.[57] It has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports populations of crimson-crowned fruit doves, blue-crowned lorikeets, Polynesian trillers and Polynesian starlings.[58]

Government and politics

[edit]

The Niue Constitution Act of 1974 vests executive authority in His Majesty the King in Right of New Zealand and in the Governor-General of New Zealand.[59] The Constitution specifies that everyday practice involves the exercise of sovereignty by Cabinet, composed of the Prime Minister (currently Dalton Tagelagi since 11 June 2020) and of three other ministers. The Prime Minister and ministers are members of the Niue Assembly, the nation's parliament.

The Assembly consists of 20 members, 14 of them elected by the electors of each village constituency, and six by all registered voters in all constituencies.[60] Electors must be New Zealand citizens, resident for at least three months, and candidates must be electors and resident for 12 months. Everyone born in Niue must register on the electoral roll.[61]

Niue has no political parties; all Assembly members are independents. The only Niuean political party to have ever existed, the Niue People's Party (1987–2003), won once (in 2002) before disbanding the following year.[62]

The Legislative Assembly elects a Speaker as its first official in the first sitting of the Assembly following an election. The speaker calls for nominations for prime minister; the candidate with the most votes from the 20 members is elected. The prime minister selects three other members to form a Cabinet, the executive arm of government.[63] General elections take place every three years, most recently on 29 April 2023.

The judiciary, independent of the executive and the legislature, includes a High Court and a Court of Appeal, with appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London.[64]

Defence and foreign affairs

[edit]Niue has operated as a self-governing state in free association with New Zealand since 3 September 1974, when the people endorsed the Constitution in a plebiscite.[65][66] Niue is fully responsible for its internal affairs. Niue's position concerning its external relations is less clear-cut. Section 6 of the Niue Constitution Act provides that: "Nothing in this Act or in the Constitution shall affect the responsibilities of Her Majesty the Queen in right of New Zealand for the external affairs and defence of Niue." Section 8 elaborates but still leaves the position unclear:

Effect shall be given to the provisions of sections 6 and 7 [concerning external affairs and defence and economic and administrative assistance respectively] of this Act, and to any other aspect of the relationship between New Zealand and Niue which may from time to time call for positive co-operation between New Zealand and Niue after consultation between the Prime Minister of New Zealand and the Prime Minister of Niue, and in accordance with the policies of their respective Governments; and, if it appears desirable that any provision be made in the law of Niue to carry out these policies, that provision may be made in the manner prescribed in the Constitution, but not otherwise."

Niue has a representative mission (High Commission) in Wellington, New Zealand.[67]

Initially, Niue's foreign relations and defence were the responsibility of New Zealand.[68]: 207 However, Niue gradually began to develop its own foreign relations, independently of New Zealand.[68]: 208 It is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum and of a number of regional and international agencies. It is not a member of the United Nations, but is a state party to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Ottawa Treaty and the Treaty of Rarotonga. The country became a member state of UNESCO on 26 October 1993.[69] It established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China on 12 December 2007.[70] The joint communique signed by Niue and China differs in its treatment of the Taiwan question from that agreed by New Zealand and China. New Zealand "acknowledged" China's position on Taiwan but has never expressly agreed with it, but Niue "recognises that there is only one China in the world, the Government of the People's Republic of China is the sole legal government representing the whole of China and Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of China."[70] Niue established diplomatic relations with India on 30 August 2012.[71] On 10 June 2014, the Government of Niue announced that Niue had established diplomatic relations with Turkey. The Honourable Minister of Infrastructure Dalton Tagelagi formalised the agreement at the Pacific Small Island States Foreign Ministers meeting in Istanbul, Turkey.[72]

People of Niue have fought as part of the New Zealand military. During World War I (1914–1918), Niue sent about 200 soldiers as part of the New Zealand (Māori) Pioneer Battalion in the New Zealand forces.[73]

Niue is not a republic, but for a number of years the ISO list of country names (ISO 3166-1) listed its full name as "the Republic of Niue". In its newsletter of 14 July 2011, the ISO acknowledged that this was a mistake and the words "the Republic of" were deleted from the ISO list of country names.[74]

Niue has no regular indigenous military forces; defence is the responsibility of New Zealand.[8] The New Zealand Defence Force has responsibilities for protecting the territory as well as its offshore exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The total offshore EEZ is about 317,500 square kilometres (122,600 sq mi).[75] Vessels of the Royal New Zealand Navy can be employed for this task including its Protector-class offshore patrol vessels.[76] These naval forces may also be supported by Royal New Zealand Air Force aircraft, including P-8 Poseidons.[77] New Zealand forces also provide additional logistics and specialized support for Niue.[78]

However, these forces are limited in size with, for instance, only infrequent air force overflights of the EEZ.[54] In 2023 New Zealand's forces were described by the Government as "not in a fit state" to respond to regional challenges.[79][80] New Zealand's subsequently announced "Defence Policy and Strategy Statement" noted that shaping the security environment, "focusing in particular on supporting security in and for the Pacific" would receive enhanced attention.[81]

Economy

[edit]

Niue's gross domestic product (GDP) was NZ$17 million in 2003,[82] or US$10 million at purchasing power parity.[8] Its GDP had increased to US$24.9 million by 2016.[citation needed] Niue uses the New Zealand dollar.

The Niue Integrated Strategic Plan (NISP) is the national development plan, setting national priorities for development. Cyclone Heta set the island back about two years from its planned timeline to implement the NISP, since national efforts concentrated on recovery efforts. In 2008, Niue had yet to fully recover. After Heta, the government made a major commitment to rehabilitate and develop the private sector.[83] In 2004, the New Zealand government allocated $1 million for the private sector,[84] and spent it on helping businesses devastated by the cyclone, and on construction of the Fonuakula Industrial Park.[citation needed] This industrial park is now completed and some businesses are already operating from there. The Fonuakula Industrial Park is managed by the Niue Chamber of Commerce, a not-for-profit organisation providing advisory services to businesses.[citation needed]

Joint ventures

[edit]The government and the Reef Group from New Zealand started two joint ventures in 2003 and 2004 to develop fisheries and a 120-hectare (300 acre) noni juice operation.[85] Noni fruit comes from Morinda citrifolia, a small tree with edible fruit. Niue Fish Processors Ltd (NFP) is a joint venture company processing fresh fish, mainly tuna (yellowfin, big eye and albacore), for export to overseas markets. NFP operates out of a fish plant in Amanau Alofi South, completed and opened in October 2004.[86]

Mining

[edit]In August 2005, an Australian mining company, Yamarna Goldfields, suggested that Niue might have the world's largest deposit of uranium. By early September these hopes were seen as overoptimistic,[87] and in late October the company cancelled its plans, announcing that exploratory drilling had identified nothing of commercial value.[88] The Australian Securities and Investments Commission filed charges in January 2007 against two directors of the company, now called Mining Projects Group Ltd, alleging that their conduct had been deceptive and that they engaged in insider trading.[89] This case was settled out of court in July 2008, both sides withdrawing their claims.[90]

Debt

[edit]On 27 October 2016, Niue officially declared that all its national debt was paid off.[91] The government plans to spend money saved from servicing loans on increasing pensions and offering incentives to lure expatriates back home. However, Niue is not entirely independent. New Zealand pays $14 million in aid each year and Niue still depends on New Zealand economically. Premier Toke Talagi said Niue managed to pay off US$4 million of debt and had "no interest" in borrowing again, particularly from countries such as China that offered "huge sums that other Pacific islands find too tempting to resist".[91]

Revenue

[edit]Remittances from expatriates were a major source of foreign exchange in the 1970s and early 1980s. Continuous migration to New Zealand has shifted most members of nuclear and extended families there, removing the need to send remittances back home. In the late 1990s, PFTAC conducted studies on the balance of payments, which confirmed that Niueans are receiving few remittances but are sending more money overseas.[92]

Foreign aid

[edit]Foreign aid is a significant source of income, accounting for approximately a third of Niue's annual government revenue.[93] Most aid comes from New Zealand,[8] which has a legal obligation to provide economic and administrative assistance.[94] Other sources of revenue for the government are taxation and trading activities, such as philatelic services and the lease of phone lines.[95]

Offshore banking

[edit]The government briefly considered offshore banking. Under pressure from the U.S. Treasury, Niue agreed to end its support for schemes designed to minimise tax in countries like New Zealand. Niue provides automated Companies Registration, administered by the New Zealand Ministry of Economic Development. The Niue Legislative Assembly passed the Niue Consumption Tax Act in the first week of February 2009, and the 12.5% tax on goods and services was expected to take effect on 1 April 2009. Income tax has been lowered, and import tax may be reset to zero except for "sin" items like tobacco, alcohol and soft drinks. Tax on secondary income has been lowered from 35% to 10%, with the stated goal of fostering increased labour productivity.[96]

Internet

[edit]In 1997, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), under contract with the U.S. Department of Commerce, assigned the Internet Users Society-Niue (IUS-N), a private non-profit, as manager of the .nu top-level domain on the Internet. The stated purpose of IUS-N was to use revenue from .nu domain registrations to support Internet services for Niue. According to a letter to ICANN in 2007, IUS-N's auditors reported an investment of US$3 million in Niue's Internet services between 1999 and 2005, funded by domain registration revenue. In 1999, an agreement was reached between IUS-N and the Government of Niue, recognizing IUS-N's management of the .nu ccTLD under IANA's authority. This agreement included commitments to provide free Internet services to government departments and citizens.

A subsequent government disputed this agreement and sought compensation from IUS-N.[97] A Commission of Inquiry in 2005 found no merit in these claims, which were dismissed by the government in 2007.[98] Starting in 2003, IUS-N began expanding Wi-Fi coverage throughout the capital village of Alofi and in several nearby villages and schools, and has been expanding Wi-Fi coverage into the outer villages since then, making Niue the first Wi-Fi nation.[99] Additionally, IUS-N provides secure DSL connections for government departments at no cost.

On December 16, 2020, the Government of Niue initiated proceedings to reassign control of its national webspace, .nu, from the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to itself. This action reflects ongoing efforts by Niue to assert control over its digital assets amid concerns about national sovereignty and economic benefits associated with the .nu domain.[100]

Agriculture

[edit]

Agriculture is very important to the lifestyle of Niueans and the economy, and around 204 square kilometres (79 sq mi) of the land area are available for agriculture.[101] Subsistence agriculture is very much part of Niue's culture, where nearly all the households have plantations of taro.[102] Taro is a staple food, and the pink taro now dominant in the taro markets in New Zealand and Australia is a product of Niue. This is one of the naturally occurring taro varieties on Niue, and has a strong resistance to pests. The Niue taro is known in Samoa as "talo Niue" and in international markets as pink taro. Niue exports taro to New Zealand. Tapioca or cassava, yams and kumara also grow very well,[8] as do different varieties of bananas. Coconut meat, passionfruit and limes dominated exports in the 1970s, but in 2008 vanilla, noni and taro were the main export crops.

Most families grow their own food crops for subsistence and sell their surplus at the Niue Makete in Alofi, or export to New Zealand.[103] Coconut crab, or uga, is also part of the food chain; it lives in the forest and coastal areas.[104]

In 2003, the government made a commitment to develop and expand vanilla production with the support of NZAID. Vanilla has grown wild on Niue for a long time. The industry was devastated by Cyclone Heta in early 2004, but has since recovered.[105]

The last agricultural census was in 1989.[106]

Tourism

[edit]

Along with fisheries and agriculture, tourism is one of the three priority economic sectors for economic development. In 2006, estimated visitor expenditure reached US$1.6 million (equivalent to about $2M in 2024). The only airport is Niue International Airport, and Air New Zealand is the sole airline, flying twice a week from Auckland.[107][108] In the early 1990s Niue International Airport was served by a local airline, Niue Airlines, but it closed in 1992.

The sailing season begins in May. Alofi Bay has many mooring buoys and yacht crews can lodge at Niue Backpackers.[109] The anchorage in Niue is one of the least protected in the South Pacific. Other challenges of the anchorage are a primarily coral bottom and many deep spots.[110]

Niue became the world's first dark-sky country in March 2020. The entire island maintains standards of light development and keeps light pollution limited. Guided Astro-tours will be offered for tourists, led by trained Niuean community members.[111]

Matavai Resort controversy

[edit]New Zealand businessman Earl Hagaman, founder of Scenic Hotel Group, was awarded a contract in 2014 to manage the Matavai Resort in Niue after he made a $101,000 political donation to the New Zealand National Party, which at that time led a minority government in New Zealand. The resort is subsidized by New Zealand, which wants to bolster tourism there. In 2015, New Zealand announced $7.5m in additional funding for expansion of the resort.[citation needed]

The selection of the Matavai contractor was made by the Niue Tourism Property Trust, whose trustees are appointed by New Zealand Foreign Affairs minister Murray McCully. Prime Minister John Key said he did not handle campaign donations, and that Niue premier Toke Talagi has long pursued tourism as a growth strategy. McCully denied any link between the donation, the foreign aid and the contractor selection.[112]

Information technology

[edit]

The Census of Households and Population in 1986 was the first to be processed using a personal computer with the assistance of David Marshall, FAO adviser on agricultural statistics, advising UNFPA demographer Lawrence Lewis and Niue government statistician Bill Vakaafi Motufoou to switch from using manual tabulation cards. In 1987, Statistics Niue got its new personal computer NEC PC AT use for processing the 1986 census data; personnel were sent on training in Japan and New Zealand to use the new computer. The first Computer Policy was developed and adopted in 1988.[113]

In 2003, Niue became the first country in the world to provide state-funded wireless internet to all inhabitants.[114][115]

In August 2008, it has been reported that all school students have what is known as the OLPC XO-1, a specialised laptop by the One Laptop per Child project designed for children in the developing world.[116][117]

In July 2011, Telecom Niue launched pre-paid mobile services (Voice/EDGE – 2.5G) as Rokcell Mobile based on the commercial GSM product of vendor Lemko. Three BTS sites will cover the nation. International roaming is not currently available.[citation needed]

In January 2015, Telecom Niue completed the laying of the fibre optic cable around Niue connecting all the 14 villages, making land line phones and ADSL internet connection available to households.[118]

Niue was connected to the Manatua Fibre Cable in 2021.[119]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 4,015 | — |

| 1911 | 3,943 | −1.8% |

| 1921 | 3,750 | −4.9% |

| 1931 | 3,797 | +1.3% |

| 1945 | 4,253 | +12.0% |

| 1951 | 4,553 | +7.1% |

| 1961 | 4,864 | +6.8% |

| 1971 | 4,990 | +2.6% |

| 1981 | 3,281 | −34.2% |

| 1991 | 2,239 | −31.8% |

| 2001 | 1,788 | −20.1% |

| 2011 | 1,611 | −9.9% |

| 2022 | 1,681 | +4.3% |

| Source:[120][7] | ||

The 2022 Niue Census of Population and Housing enumerated a population of 1,681, a decrease of around 2.2 percent over the 2017 figure. Of this, 1,564 (93 percent) considered Niue to be their place of usual residence, a decrease of 27 from 2017. Migration is a significant driver of population change, with 221 residents aged 5 and over not living in Niue five years prior to the census, suggesting substantial immigration.[7] Niue has a population density of 6.0 inhabitants per square kilometre (16/sq mi). The majority of the population is located in the villages of Alofi South (25.2 percent), Alofi North (11.1 percent), Hakupu, and Tamakautoga (both 10.7 percent).[7]

Ethnicity

[edit]According to the 2022 census, 1,153 (73.7 percent) of residents identified of Niuean ethnicity. Of this, 1070 (68.4 percent) identified as Niuean and 83 (5.3 percent) identified as part-Niuean.[7] 411 residents identified as other ethnic groups, among them 68 Tuvaluans, 76 Samoans, 77 Tongans, 63 Fijians, and 27 Filipinos.[7]

Languages

[edit]The official languages of Niue are English and Niuean, a Polynesian language related to Tongan and Samoan.[8] As of 2022, 1,014 (69.7 percent) of residents reported proficiency in speaking Niuean. The number of residents who speak Niuean has been in decline since 2006.[7]

Religion

[edit]According to the 2022 census, the majority of Niueans are religious, with only 112 (7.2 percent) of residents reporting no religion. 961 (61.4 percent) of Niueans are affiliated with the Ekalesia Niue Church, a Christian denomination. 137 (8.8 percent) are affiliated with the Church of Latter Day Saints, and 114 (7.3 percent) are affiliated with the Catholic Church.[7]

Health

[edit]Healthcare in Niue is administered by the Niue Department of Health (NDOH), with the Niue Foou Hospital serving as a hub for the majority of the country's healthcare services. The hospital provides only primary and secondary care, and patients requiring tertiary care are sent to hospitals in New Zealand. Specialist healthcare providers from New Zealand visit Niue regularly to provide clinics.[121]

Education

[edit]

Niue has two public schools: the Niue Primary School and the Niue High School. The primary school serves students from years one to six, and the high school from years seven to 13. Enrolment is mandatory for children ages five to 16. Students in Niue have the opportunity to earn scholarships or a university entrance certificate to further their education in New Zealand or other countries.[7]

According to the 2022 census, trade certifications or diplomas are the highest formal education attained by men in Niue at 19.5 percent, a decrease from 22 percent in 2017. Female Niueans have a higher likelihood of acquiring a university education, with 25.9 percent of females completing a degree compared to 22.1 percent of males. 28.7 percent of the Niueans aged 60 and above had no qualifications.[7]

Culture

[edit]

Niue is the birthplace of New Zealand artist and writer John Pule. Author of The Shark That Ate the Sun, he also paints tapa cloth inspired designs on canvas.[122] In 2005, he co-wrote Hiapo: Past and Present in Niuean Barkcloth, a study of a traditional Niuean artform, with Australian writer and anthropologist Nicholas Thomas.[123]

Taoga Niue is a new Government Department responsible for the preservation of culture, tradition and heritage. Recognising its importance, the Government has added Taoga Niue as the sixth pillar of the Niue Integrated Strategic Plan (NISP).[124]

Media

[edit]Niue has two broadcast outlets, Television Niue and Radio Sunshine, managed and operated by the Broadcasting Corporation of Niue, and one newspaper, the Niue Star.[125]

Arts and culture

[edit]Hiapo is a traditional art form in Niue, it is considered similar to Siapo or Ngatu Tonga. Hiapo is made by beating the inner bark of the paper mulberry tree until it becomes a pliable tapa cloth, which is then decorated using natural dyes and stencils. Some Niuean hiapo artists include John Pule and Cora-Allan Wickliffe.[126]

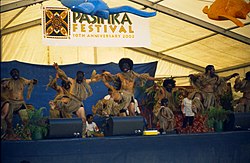

Takalo is a Niuean war dance traditionally performed prior to engaging the enemy in battle, later being performed at formal occasions.[127][128]

Museums

[edit]In 2004, Cyclone Heta destroyed the Huanaki Cultural Centre & Museum. The damage resulted in the destruction of the buildings, but also the loss of over 90% of the museum's collections.[129][130][131] In 2018 Fale Tau Tāoga Museum opened, a new national museum for Niue.[132]

Cuisine

[edit]Due to the island's location and the fact that the Niue produce a significant array of fruits and vegetables, natural local produce, especially coconut, features in many of the dishes of the islands, as does fresh seafood. Takihi, the national dish, is made from coconut cream and thinly sliced taro and papaya layered on top of each other until it forms a cake like structure. Traditionally and popularly it is wrapped in taro leaves and is cooked in an Umu (earth oven), but nowadays people cook their takihi in their ovens at home.[citation needed]

Sport

[edit]

Despite being a small country, a number of sports are popular. Rugby union is the most popular sport, played by both men and women; Niue was the 2008 FORU Oceania Cup champions.[133] Netball is played only by women. There is a nine-hole golf course at Fonuakula and a single lawn bowling green.[134] Association football is a popular sport, as evidenced by the Niue Soccer Tournament, though the Niue national football team has played only two matches. Rugby league is also a popular sport.

Niue participates in the Commonwealth Games, but unlike the Cook Islands, it is not a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and does not compete in the Olympic Games.[135] Per IOC rules, participation in the Olympics requires being "an independent State recognised by the international community".[136]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The King in right of New Zealand is represented by the Governor-General of New Zealand in relation to Niue.[2]

- ^ The Prime Minister is still referred to as the "Premier of Niue" in most governmental pages and entities, and retains the title Premier as an alternate, transitional, or quasi-official name despite the recent referendum.

- ^ /ˈnjuːeɪ/ ⓘ,[10] /niːˈjuːeɪ/; Niuean: Niuē

References

[edit]- ^ "Complete National Anthems of the World: 2013 Edition" (PDF). www.eclassical.com. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "Niue National Strategic Plan 2016–2026" (PDF). Government of Niue. 2016. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Legal Instruments and Documents Relevant to the Relationship Between New Zealand and Six Pacific Nations". New Zealand Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Repertory of Practice – Organs Supplement" (PDF). UN. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950–2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Flanagan, Matt; Sioneholo, Fanuma. "2022 Niue Census of Population and Housing Report". Statistics Niue. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Niue". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "Niue National Accounts estimates". niue.prism.spc.int. Niue Statistics Office. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Deverson, Tony; Kennedy, Graeme, eds. (2005). "Niue". The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195584516.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-558451-6. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Introducing Niue". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ "Niue Islands Village Council Ordinance 1967". Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "QuickStats About Pacific Peoples". Statistics New Zealand. 2006. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher; R. E. Asher, eds. (1994). Atlas of the World's Languages. New York: Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-4150-1925-5.

- ^ "List of member countries". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 21 August 2004.

- ^ Foster, Sophie (11 July 2025) [First published 20 July 1998]. "Niue". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Smith, Stephenson Percy (1903). Niue-fekai (or Savage) Island and its People. Wellington: Whitcombe & Tombs. pp. 36–34. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Horowitz, Anthony (2002). "8". Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before.

- ^ Marks, Kathy (9 July 2008). "World's smallest state aims to become the first smoke-free paradise island". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Langdon, Robert (1984). Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century. Canberra: Pacific Manuscripts Bureau. pp. 192–193. ISBN 0-8678-4471-X.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade C., eds. (18 October 2011). "Nukai Peniamina". Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Sage Publishing. p. 925. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- ^ "A Brief History of Niue". Niue Pocket Guide. 14 July 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, October 1853". Savage Island. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d Roberts-Wray, Kenneth (1966). Commonwealth and Colonial Law. London: Stevens & Sons. p. 897. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "Isolation Ends". The Press. 2 December 1970. p. 28. Retrieved 29 August 2025 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Russia has more subs". The Press. 27 November 1971. p. 15. Retrieved 29 August 2025 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Niue Constitution Act 1974". Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Bain, Kenneth (16 December 1992). "Obituary: Sir Robert Rex". The Independent. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Interview with Sir Robert Rex". National Library of New Zealand. 1977. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Sir Collin Tukuitonga: the newest Niuean Knight". Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences. University of Auckland. 6 June 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Niue mourns the death of a young woman". Radio New Zealand. 8 January 2004. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Niue is World's First Country to Become a Dark Sky Place". International Dark Sky Association. 7 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Remarks by President Biden at the U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit". The White House. 29 September 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Statement on the Recognition of Niue and the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations". The American Presidency Project. 25 September 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Jacobson G, Hill PJ (1980) Hydrogeology of a raised coral atoll, Niue Island, South Pacific Ocean. Journal of Australian Geology and Geophysics, 5 271–278.

- ^ Whitehead, N. E.; J. Hunt; D. Leslie; P. Rankin (June 1993). "The elemental content of Niue Island soils as an indicator of their origin" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics. 36 (2): 243–255. Bibcode:1993NZJGG..36..243W. doi:10.1080/00288306.1993.9514572. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "'NextGen' Projections for the Western Tropical Pacific: Current and Future Climate for Niue" (PDF). CSIRO. October 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Alofi, Niue". Weatherbase. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ "Capacity Building related to Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) in African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Countries: Niue Island Organic Farmers Association". European Union. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "Niue Agriculture Sector Plan 2015–2019" (PDF). Niue Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

- ^ "Niue Island Organic Farmers Association – PoetCom". www.organicpasifika.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Rogers, Simon (21 June 2012). "World carbon emissions: the league table of every country". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ "Niue". European External Action Service. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Niue – Tuila Office Tuila overview". Sunnyportal.com. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Niue: Intended Nationally Determined Contributions" (PDF). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- ^ "Niue Strategic Energy Road Map 2015–2025" (PDF).

- ^ "Niue to embrace more solar and wind power". Radio New Zealand. 3 November 2015.

- ^ [UNDP] (9 July 2025). "Niue Shapes a New Decade of Sustainable Energy Leadership at National Energy Summit 2025". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Niue – Tuila Office – Tuila overview". Sunny Portal. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ "Achievements for Niue". The European Commission's Delegation to the Pacific. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ^ "Six Island Nations Commit to 'Fossil Fuel-Free Pacific,' Demand Global Just Transition". www.commondreams.org. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ "Port Vila call to phase out fossil fuels". RNZ. 22 March 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Ligaiula, Pita (17 March 2023). "Port Vila call for a just transition to a fossil fuel free Pacific". PINA. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ a b Evans, Monica (3 November 2022). "Small island, big ocean: Niue makes its entire EEZ a marine park". Mongabay. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ a b Gardner, Rhys O. (2020). "The naturalised flora of Niue". Papahou: Records of the Auckland Museum. 55: 101–155. doi:10.32912/RAM.2020.55.5. ISSN 1174-9202. JSTOR 27008993. Wikidata Q106828180.

- ^ "Huvalu Forest Conservation Area (Niue)". Pacific Islands Protected Area Portal. Pacific Regional Environment Programme. 2021. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Huvalu and environs". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Niue Constitution Act 1974: Schedule 2: The Constitution of Niue (English language version), s1". legislation.govt.nz. 29 August 1974. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Niue's Government and Politics". Government of Niue. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "Enroll to vote". New Zealand Government. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Niue's only party dissolved". RNZ. 21 July 2003. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Constitution of Niue, s2.

- ^ "Niuean criminal court system". Association of Commonwealth Criminal Lawyers. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ Masahiro Igarashi, Associated Statehood in International Law, p. 167

- ^ "Towards self-government, or something". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. 45, no. 10. 1 October 1974. p. 7. Retrieved 19 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Government of Niue – Niue & New Zealand High Commission – Komisina Tokoluga Niue mo Niu Silani". www.gov.nu. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b McDonald, Caroline (2018). Decolonisation and Free Association: The Relationships of the Cook Islands and Niue with New Zealand (PDF) (PhD). Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Member States". UNESCO. October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Full text of joint communiqué on the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Niue". Xinhua News Agency. 12 December 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ^ "India establishes Diplomatic Relations with Niue". Ministry of External Affairs of India. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Foreign Minister Davutoğlu "In the last six years, we have taken significant steps to strengthen our relations with Pacific Island States"". Republic of Türkiye. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Pointer, Margaret; Folau, Kalaisi (2000). Tagi Tote e Loto Haaku, My Heart Is Crying a Little: Niue Island Involvement in the Great War, 1914–1918. Institute of Pacific Studies. Suva, Fiji: University of the South Pacific. ISBN 978-9-8202-0157-6.

- ^ "ISO 3166-1 Newsletter VI-9 "Name changes for Fiji, Myanmar as well as other minor corrections"" (PDF). 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

Correct the long name which was incorrect[.]

- ^ Turrell, Claire (30 May 2022). "Tiny Pacific island nation declares bold plan to protect 100% of its ocean". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "Illegal Fishing Targeted" (PDF). Navy Today. No. 261. Royal New Zealand Navy. December 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "More than 20 fishing vessels inspected during New Zealand-led South Pacific fisheries patrol". New Zealand – Ministry for Primary Industries. 11 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "NZ Navy Hydrographers get to work mapping Niue's unique landscape". New Zealand Defence Force. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "New Zealand Military 'Not in a Fit State,' Government Says". The Defence Post. 4 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Cutting-edge new aircraft have increased NZ's surveillance capacity – but are they enough in a changing world?". The Conversation. 26 July 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "Defence Policy and Strategy Statement 2023" (PDF). New Zealand Government. August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Country Information Paper – Niue". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ "Niue Foou - A New Niue: Cyclone Heta Recovery Plan" (PDF). Government of Niue. April 2004. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "NZ gives $5 million to help rebuild Niue". New Zealand Government. 21 January 2004. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Reef Group looks to NZ for help Niue projects". Radio New Zealand. 13 March 2008.

- ^ "Two new processing plants officially opened on Niue". RNZ. 18 October 2004. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Yamarna loses passion for Niue's uranium". The Age. 6 September 2005. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "NIUE: No Mineable Uranium, Says Exploration Company". Pacific Magazine. 3 November 2005. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "ASIC takes action against directors of Melbourne mining company" (Press release). Australian Securities and Investments Commission. 23 January 2007. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "ASIC discontinues proceedings against directors of Melbourne mining company" (Press release). Australian Securities and Investments Commission. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ^ a b Ainge Roy, Eleanor (27 October 2016). "Land that debt forgot: tiny Pacific country of Niue has no interest in loans". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Pacific Financial Technical Assistance Centre". PFTAC. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Financial Snapshot: 1 July 2020 – 31 January 2021" (PDF). Department of Finance and Planning. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Niue Constitution Act 1974: section 7". legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Niue: Country Classification" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. October 2021. p. 9. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "12.5% Niue Consumption Tax from 1 April". Niue Business News. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009.

- ^ Rhoads, Christopher (29 March 2006). "On a tiny island, catchy Web name sparks a battle". Post-gazette.com. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ "Niue government criticised over internet stance". RNZI. 13 November 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ "WiFi Nation". WiFi Nation. Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "'Digital colonisation': A tiny island nation just launched a major effort to win back control of its top-level internet domain". 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles: Niue". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. January 2009. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Pollock, Nancy J. (1979). "Work, wages, and shifting cultivation on Niue". Journal of Pacific Studies. 2 (2). Pacific Institute: 132–43.

- ^ "Niue Agriculture Sector Plan 2015–2019" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. p. 12. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Eagles, Jim (23 September 2010). "Niue: Hunting the uga". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Pacific Success – Niue Vanilla International". Pacific Trade Invest Australia. 8 January 2019. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Niue Agricultural Census 1989 – Main Results" (PDF). United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 1989. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "Air NZ flights in 2024". Stuff (Fairfax). 2023.

- ^ "Niue Tourism". Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ "Sailing Season Commences on Niue – Niue". Niueisland.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "The Rock of the Pacific – Niue". 20 November 2008. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008.

- ^ Valerie Stimack (10 March 2020). "Pacific Island Niue Becomes The World's First Dark Sky Nation". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020.

- ^ Jo Moir (18 April 2016). "Foreign Affairs minister Murray McCully denies link between party donation and Niue contract". Stuff.

- ^ "National E-commerce Assessment: Niue" (PDF). Pacific Islands Forum. 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Light Reading – Networking the Telecom Industry". Unstrung.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2003. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Creating a Wireless Nation" (PDF). IUSN White Paper. July 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "One laptop for every Niuean child". BBC News. 22 August 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Niue schoolchildren all have laptops". RNZ. 22 August 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ [GB Worldwide] (2015). "Spotlight on G.B. Niue" (PDF). Girls' Brigade International. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "NIUE'S MANATUA CABLE GOES LIVE AND DELIVERS WORLD CLASS ULTRA FAST FIBRE INTERNET". Pacific Online. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Population". Statistics Niue. 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2025.

- ^ "Government of Niue Health Strategic Plan 2011–2021" (PDF). Government of Niue. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Whitney, Scott (1 July 2002). "The Bifocal World of John Pule: This Niuean Writer and Painter Is Still Searching for a Place To Call Home". Pacific Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008..

- ^ "John Pule and Nicholas Thomas. Hiapo: Past and present in Niuean barkcloth". New Zealand: Otago University Press. Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Niue National Strategic Plan 2009 – 2013" (PDF). Government of Niue. p. 4. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Le Programme international pour le développement de la communication de l'UNESCO soutient le journal de Niue" (in French). UNESCO. 16 July 2002. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Pule, John; Thomas, Nicholas (2005). Hiapo: Past and present in Niuean barkcloth. University of Otago Press. ISBN 978-1-8773-7200-1.

- ^ McLean, Mervyn (1999). Weavers of Song: Polynesian Music and Dance. Auckland University Press. ISBN 978-1-8694-0212-9.

- ^ "Ponataki" (PDF). New Zealand: Ministry of Pacific Peoples. 2020. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Barnett, Jon; Ellemor, Heidi (2007). "Niue after Cyclone Heta". Australian Journal of Emergency Management. 22 (1): 3–4. ISSN 1324-1540.

- ^ Barnett, Jon (1 June 2008). "The Effect of Aid On Capacity To Adapt To Climate Change: Insights From Niue". Political Science. 60 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1177/003231870806000104. ISSN 0032-3187. S2CID 155080576.

- ^ Pasisi, Jessica Lili (2020). Kitiaga mo fakamahani e hikihikiaga matagi he tau fifine Niue: tau pūhala he tau hiapo Niue women's perspectives and experiences of climate change: a hiapo approach (PhD thesis). The University of Waikato. hdl:10289/13380.

- ^ "Art & Culture". Niue Tourism. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Niue take Oceania Cup rugby union final". Radio Australia. 1 September 2008. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games: How a 'frankly embarrassing' selection dispute soured Niue's shot at lawn bowls success". Stuff. 10 August 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Niue". insidethegames.biz. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "127th IOC Session comes to close in Monaco". International Olympic Committee. 9 December 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

The NOC of Kosovo met the requirements for recognition as outlined in the Olympic Charter. These include the sport and technical requirements as well as the definition of "country" as defined in Rule 30.1 – "an independent State recognised by the international community". Kosovo is recognised as a country by 108 of the 193 UN Member States.

Further reading

[edit]- Chapman, Terry (1976). The Decolonisation of Niue. New Zealand Institute of International Affairs (Thesis). Wellington: Victoria University Press. OCLC 3749817.

- Loeb, Edwin M. (1926). History and Traditions of Niue. Honolulu, Hawaii: Bernice P. Bishop Museum. OCLC 5251439.

- Pointer, Margaret (2015). Niue 1774–1974: 200 Years of Contact and Change. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5586-4.

- Pointer, Margaret (2018). Niue and the Great War. Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press. ISBN 978-1-9885-3123-6.

- Terry, James P.; Murray, Warwick E. (2004). Niue Island: Geographical Perspectives on the Rock of Polynesia. International Scientific Council for Island Development. ISBN 9-2990-0230-4.

- Thomson, Basil C. (1902). . London: J. Murray – via Wikisource.

- Tregear, Edward (March 1893). "Niue: or Savage Island". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 2: 11–16. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010.

External links

[edit]- Government of Niue

- Niue Tourism Office

- Niue from UCB Libraries GovPubs

Wikimedia Atlas of Niue

Wikimedia Atlas of Niue

History

Polynesian Settlement and Pre-European Society

Polynesians originating from Samoa are recorded as the first settlers of Niue around 900 CE, establishing the island's foundational population through voyaging canoes. A second major migration wave from Tonga followed in the 16th century, contributing to cultural and genetic admixture, while smaller groups possibly arrived from northern atolls like Pukapuka.[1][5][6] These migrations reflect broader Polynesian expansion patterns, where navigators exploited seasonal winds and currents to reach isolated central Pacific landfalls, though direct archaeological confirmation for Niue remains limited due to the island's coral limestone terrain eroding surface sites.[7] Oral traditions preserved in Niuean mythology describe the island's emergence and early habitation, often linking settlement to divine or ancestral figures navigating from western Polynesia, with earthquakes and water scarcity motifs underscoring environmental challenges faced by arrivals. Pre-European Niuean society developed as a decentralized gerontocracy across 14 independent villages, each autonomous and led by a hereditary chief (tuangi or matapule) who mediated disputes and rituals, with authority reinforced by respect for elders and male lineage holders.[8] Social organization prioritized kinship ties, village loyalty, and communal labor, fostering a hierarchical yet cooperative structure where obedience to seniors maintained order in a resource-scarce environment of limited arable land—approximately 100 square kilometers—constraining population growth to an estimated few thousand at most.[1] Subsistence relied on shifting agriculture cultivating taro, yams, and breadfruit in terraced plots, supplemented by lagoon and reef fishing, shellfish gathering, and pandanus weaving for mats and tools; inter-village raids occasionally disrupted peace, but fortified hilltop settlements (motu) provided defense against such conflicts.[8] Cultural practices emphasized oral genealogy, tattooing for status, and rituals tied to ancestors and natural cycles, with caves serving as sacred repositories for burials and artifacts, evidencing long-term habitation patterns. Archaeological surveys reveal pottery fragments and adze tools consistent with Samoan-Tongan influences, supporting migration narratives, though the absence of Lapita ware distinguishes Niue from earlier West Polynesian phases, indicating later colonization.[9] This isolation preserved distinct traditions until European contact, with society adapting to the island's uplifted coral plateau through rainwater collection and agroforestry, avoiding overexploitation that plagued denser Polynesian settlements elsewhere.[10]European Contact and Missionary Era

The first recorded European sighting of Niue occurred on June 21, 1774, when Captain James Cook approached the island during his second voyage across the Pacific Ocean.[11] Cook dispatched landing parties on three separate occasions, but each was repelled by Niuean inhabitants who hurled stones and refused access, prompting him to dub the island "Savage Island" in reference to the perceived hostility.[12][6] No Europeans disembarked during this encounter, and Niue remained isolated from sustained foreign interaction for decades thereafter.[13] Intermittent visits by American and British whalers and traders commenced in the early 19th century, introducing iron tools, muskets, and alcohol in exchange for provisions like yams and coconuts, though these contacts were brief and often tense due to Niuean wariness.[14] The London Missionary Society (LMS) initiated evangelistic efforts in 1830, when its agent John Williams briefly landed—marking the first documented European disembarkation—and attempted to deposit Polynesian teachers, but they were rejected and the mission aborted.[6][11] Renewed LMS attempts in the 1840s involved dispatching Samoan-trained teachers, including a Niuean convert named Peniamina who returned permanently on October 26, 1846, to proselytize among his kin.[15][16] Peniamina's preaching catalyzed rapid adoption of Christianity, with conversions accelerating from 1846 onward as tribal leaders embraced the faith, which imposed prohibitions on warfare, infanticide, and polygamy, thereby halting chronic inter-village conflicts that had previously claimed up to 20% of the population in periodic raids.[15] By 1849, a significant portion of Niueans had converted, and the process culminated in near-universal acceptance by the 1850s, leaving only isolated holdouts.[17] The arrival of William George Lawes in 1861 as the first resident European LMS missionary solidified these gains, introducing systematic schooling, Bible translation into the Niuean language, and church governance that fostered social cohesion under a single denomination.[18][15] Lawes documented the transformation, noting how Christianity supplanted animistic practices and chief-driven vendettas with communal worship and moral codes derived from Protestant doctrine.[19]New Zealand Colonial Administration

Niue was annexed to New Zealand on 11 June 1901 through an Order in Council that extended New Zealand's boundaries to include the island, following a brief period as a British protectorate declared in 1900 after negotiations led by New Zealand Premier Richard Seddon with local chiefs.[5] [6] The annexation integrated Niue into New Zealand's colonial administration alongside the Cook Islands, with governance initially centered on an Island Council presided over by a resident commissioner appointed from New Zealand, the first arriving in 1902.[20] This structure emphasized centralized control from Wellington, with the commissioner enforcing policies on health, education, and economic development while maintaining authority over local affairs.[21] Under New Zealand administration, Niueans acquired New Zealand citizenship effective 1 January 1949 via the British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, enabling significant emigration that reduced the island's population from over 5,000 in the 1950s to lower levels by the 1970s due to opportunities in New Zealand.[22] [23] Administrative reforms included the establishment of the first elected Niuean Legislative Assembly in 1960, marking a shift toward limited local representation, though the resident commissioner retained substantial veto powers until partial delegation of authority in 1966.[24] New Zealand provided economic and infrastructural support, including medical services and agricultural improvements, but the period was marked by tensions over paternalistic governance.[25] A notable incident occurred on 17 August 1953 when Resident Commissioner Cecil Hector Larsen was murdered by three Niuean men, who escaped from custody and attacked him at his residence outside Alofi; the assailants cited grievances over Larsen's rigorous enforcement of colonial regulations, including punitive measures against locals, though official accounts portrayed him as a dedicated administrator.[26] [27] The three were convicted and initially sentenced to death, with a gallows constructed, but the sentences were ultimately commuted, highlighting strains in colonial authority and local resentment toward perceived overreach.[28] This event underscored broader challenges in balancing administrative efficiency with cultural sensitivities during the era.[29]Path to Self-Government in Free Association

Niue remained under New Zealand's colonial administration from 1901, following the annexation by New Zealand after British protectorate status, until moves toward greater autonomy accelerated in the early 1970s amid broader decolonization pressures in the Pacific.[30] Discussions between Niuean leaders and New Zealand officials focused on balancing self-determination with economic and security dependencies, as Niue's small population and limited resources made full independence risky without continued New Zealand support for citizenship, aid, and external relations.[31] A constitutional referendum held on October 19, 1974, presented Niueans with options including continued administration, full independence, or self-government in free association with New Zealand; voters approved the latter by a substantial majority, reflecting a preference for internal autonomy while retaining New Zealand citizenship and assistance.[32] [33] The Niue Constitution Act 1974, enacted by the New Zealand Parliament, formalized this status effective October 19, 1974, establishing Niue as a self-governing state where the Niue Assembly handles domestic legislation, the Premier leads the executive, and New Zealand retains responsibility for defense, foreign affairs, and certain international representation.[34] [35] This free association arrangement, distinct from full sovereignty, was endorsed by a United Nations General Assembly resolution on December 13, 1974, affirming Niue's exercise of self-determination through the referendum outcome, though it preserved Niue's place within the Realm of New Zealand under the shared monarch.[36] The path emphasized pragmatic interdependence over separation, as Niuean leaders prioritized access to New Zealand markets, migration rights, and budgetary aid—averaging tens of millions annually—to sustain viability amid geographic isolation and vulnerability to economic shocks.[31] No subsequent referenda have altered this framework, underscoring its stability despite occasional tensions over fiscal oversight.[37]Post-1974 Developments and Challenges

Following the adoption of its constitution on 19 October 1974, Niue established a parliamentary democracy with full responsibility for internal affairs, while New Zealand retained control over defense and foreign relations under the free association arrangement.[38] In the ensuing decades, Niue has navigated political stability through periodic elections and constitutional refinements, including a 2024 referendum that passed amendments renaming the head of government from Premier to Prime Minister and redesignating the Audit Office as the Office of the Auditor-General, reflecting efforts to modernize governance structures and assert Pacific identity.[39] These changes, approved by simple majorities among 717 voters, underscore Niue's commitment to self-governance amid ongoing debates about the viability of its small-scale administration.[40] However, no formal push for full independence has emerged since the 1974 referendum, where voters rejected it in favor of the current status to maintain economic ties with New Zealand.[41] Economically, Niue remains heavily reliant on New Zealand aid, which constitutes a substantial portion of government revenue, alongside remittances from the Niuean diaspora and limited tourism centered on its coral reefs and beaches.[3] The island's subsistence-based economy has faced contraction, prompting measures such as halving the public service workforce in the early 2000s to curb expenditures, though poverty persists in some households despite broad access to basic infrastructure.[42] Population decline exacerbates these strains, with net emigration to New Zealand driving a negative growth rate of -0.03% as of 2021, reducing resident numbers to approximately 1,600 and straining labor availability for sectors like agriculture and public services.[43] This outward migration, ongoing since the mid-20th century, has hollowed out communities, prompting discussions on sustainability without altering the free association framework.[5] Natural disasters have compounded vulnerabilities, most notably Tropical Cyclone Heta in January 2004, a Category 5 storm with wind gusts up to 296 km/h that devastated northwestern coastlines, destroyed buildings in the capital Alofi, and claimed one life while erasing 90% of the national museum's artifacts and records.[44][45] The cyclone's massive waves, exceeding 50 meters in height offshore, eroded reefs and reshaped terrain, highlighting Niue's exposure to climate-driven events in the South Pacific cyclone belt.[46] Recovery efforts, aided by international relief, rebuilt infrastructure but underscored long-term challenges like rising sea levels and resource scarcity, with Niue now prioritizing strategic planning for resilience over the next 50 years as reflected in its 2024 anniversary commemorations.[41][47]Geography

Location and Physical Description

Niue is situated in Oceania, as an island in the South Pacific Ocean east of Tonga.[1] Its geographic coordinates are 19°02′S 169°52′W.[1] The island is located approximately 2,400 kilometers northeast of New Zealand.[48] Niue consists of a single landmass with an area of 260 square kilometers and no significant inland water bodies.[1] The coastline extends 64 kilometers around the island.[48] Physically, Niue is one of the world's largest coral islands, characterized as a raised coral atoll with steep limestone cliffs fringing the coast and a central plateau.[1] The elevation reaches a maximum of 80 meters at an unnamed point 1.4 kilometers east of Hikutavake, while the lowest point is at sea level along the Pacific Ocean shores.[1] A coral reef surrounds the island, interrupted by only one major break in the central western coast.[1]Geological Formation and Terrain

Niue is a raised coral atoll primarily composed of Pleistocene-age limestone formed from fossilized coral reefs accumulated on a subsiding volcanic basement. The island's geological structure results from tectonic uplift that exposed the former reef flat and lagoon floor, creating a broad carbonate platform without significant volcanic exposures at the surface. This uplift, occurring over the last 1-2 million years, elevated the land to its current position, with the limestone exhibiting karst features due to dissolution by rainwater.[49][50][51] The terrain consists of a flat to gently undulating central plateau reaching a maximum elevation of 68 meters above sea level, ringed by steep limestone cliffs that drop sharply to the surrounding ocean. These coastal cliffs, often exceeding 30 meters in height, feature dramatic erosional landforms such as chasms, arches, and sea caves, particularly along the northern and western shores. The plateau's surface is marked by solution pits, pinnacles, and an intricate network of subsurface drainage, contributing to the absence of permanent rivers or streams as precipitation infiltrates the highly permeable and fractured rock.[52][53][54] Notable geological sites include the Talava Arches and Avaiki Cave, which exemplify the island's coastal karst morphology shaped by wave action and subaerial weathering. The limestone includes dolomite layers formed through processes like brine reflux, adding to the island's significance in carbonate sedimentology studies.[54]Climate and Natural Hazards

Niue experiences a tropical rainforest climate characterized by consistently high temperatures and significant rainfall throughout the year, with minimal seasonal variation in temperature. The annual average temperature is approximately 24°C, with daytime highs typically ranging from 24°C to 29°C and seasonal differences of only about 4°C between the warmer wet period and cooler dry period.[55] Humidity remains high year-round, contributing to muggy conditions, while average annual rainfall totals around 2,000 mm, concentrated during the wet season.[56] The island's seasons divide into a hot, wet period from November to April, marked by higher precipitation averaging up to 250 mm per month and increased risk of heavy rains, and a cooler, drier period from May to October with monthly rainfall dropping to 80–100 mm.[57][58] Trade winds moderate temperatures during the dry season, providing relief from the heat, though occasional rain spells persist.[59] Tropical cyclones pose the primary natural hazard to Niue, occurring predominantly between November and April within the South Pacific cyclone belt, with 63 such events passing within 400 km of the capital Alofi between 1969 and 2010.[55] Notable impacts include Cyclone Ofa in February 1990, which caused widespread damage to infrastructure and agriculture, and Category 5 Cyclone Heta in January 2004, which destroyed 90% of artifacts in the national museum, damaged homes, and led to significant economic losses estimated in millions of USD.[60][44] On average, Niue incurs about 0.9 million USD in annual losses from cyclones and earthquakes combined, with cyclones driving the majority due to their frequency and severity on the island's raised coral terrain.[61] Earthquake risk is classified as very low, though the proximity to the Tonga Trench introduces potential for seismic activity.[62] Tsunamis represent a moderate threat, with over a 40% probability of a damaging event in the next 50 years, potentially triggered by regional quakes and affecting coastal areas within minutes.[63] Climate change exacerbates vulnerabilities through rising sea levels, which threaten Niue's underground freshwater lens by saltwater intrusion, and ocean warming plus acidification leading to coral bleaching that undermines reef ecosystems vital for coastal protection and fisheries.[64][65] Sea surface temperature increases have already induced bleaching events, reducing coral growth and resilience against storms.[66]Environmental Conservation Efforts