Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

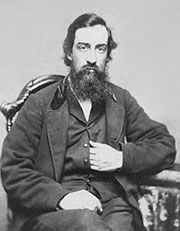

James Strang

View on WikipediaThis article's lead section may be too long. (January 2025) |

James Jesse Strang (March 21, 1813 – July 9, 1856) was an American religious leader, politician and self-proclaimed monarch. He served as a member of the Michigan House of Representatives from 1853 until his assassination.

Key Information

In 1844, he said he had been appointed as the successor of Joseph Smith as leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite),[a] a faction of the Latter Day Saint movement. Strang testified that he had possession of a letter from Smith naming him as his successor, and furthermore reported that he had been ordained to the prophetic office by an angel. His followers believe his organization to be the sole legitimate continuation of the Church of Christ founded by Smith fourteen years before.

A major contender for leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints during the 1844 succession crisis after Smith's death, Strang urged other prominent church leaders like Brigham Young and Sidney Rigdon to remain in their previous offices and to support his appointment by Smith. Young and the members of the Twelve Apostles loyal to him rejected Strang's claims, as did Rigdon, who had been a counselor in the First Presidency to Smith. This divided the Latter Day Saint movement. During his 12 years tenure as Prophet, Seer and Revelator, Strang reigned for six years as the crowned "king" of an ecclesiastical monarchy that he established on Beaver Island in the US state of Michigan. Building an organization that eventually rivaled Young's in Utah, Strang gained nearly 12,000 adherents at a time when Young was said to have about 50,000.[2][3] After Strang was killed in 1856 most of his followers rallied under Joseph Smith III and joined the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS). The Strangite church has remained small in comparison to other branches of the Latter-Day Saint movement.

Similar to Joseph Smith, who was alleged by church opponent William Marks to have been crowned King in Nauvoo prior to his death,[4] Strang taught that the chief prophetic office embodied an overtly royal attribute. Thus, its occupant was to be not only the spiritual leader of his people but their temporal king as well.[5][6] He offered a sophisticated set of teachings that differed in many significant aspects from any other version of Mormonism, including that preached by Smith. Like Smith, Strang published translations of two purportedly ancient lost works: the Voree Record, deciphered from three metal plates reportedly unearthed in response to a vision; and the Book of the Law of the Lord, supposedly transcribed from the Plates of Laban mentioned in the Book of Mormon. These are accepted as scripture by his followers, and the Church of Jesus Christ in Christian Fellowship, but not by any other Latter Day Saint church. Although his long-term doctrinal influence on the Latter Day Saint movement was minimal, several early members of Strang's organization helped to establish the RLDS Church (now known as the Community of Christ), which became (and remains) the second-largest Latter Day sect. While most of Strang's followers eventually disavowed him due to his eventual advocacy of polygamy, a small but devout remnant carries on his teachings and organization today.

In addition to his ecclesiastical calling, Strang served one full term and part of a second as a member of the Michigan House of Representatives, assisting in the organization of Manitou County. He was also at various times an attorney, educator, temperance lecturer, newspaper editor, Baptist minister, correspondent for the New York Tribune, and amateur scientist. His survey of Beaver Island's natural history was published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1854, remaining the definitive work on that subject for nearly a century,[7] while his career in the Michigan legislature was praised even by his enemies.

While Strang's organization is formally known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,[a] the term "Strangite" is usually added to the title to avoid confusing them with other Latter Day Saint bodies carrying this or similar names. This follows a typical nineteenth-century usage where followers of Brigham Young were referred to as "Brighamites," while those of Sidney Rigdon were called "Rigdonites," followers of Joseph Smith III were called "Josephites", and disciples of Strang became "Strangites".[b][8]

Childhood, education and conversion to Mormonism

[edit]James Jesse Strang was born March 21, 1813, in Scipio, Cayuga County, New York.[9] He was the second of three children, and his parents had a good reputation in their community. Strang's mother was very tender with him as a consequence of delicate health, yet she required him to render an account of all his actions and words while absent from her.[10] In a brief autobiography he wrote in 1855, Strang reported that he had attended grade school until age twelve, but that "the terms were usually short, the teachers inexperienced and ill qualified to teach, and my health such as to preclude attentive study or steady attendance." He estimated that his time in a classroom during those years totaled six months.[11][better source needed]

But none of this meant that Strang was illiterate or simple. Although his teachers "not unfrequently turned me off with little or no attention, as though I was too stupid to learn and too dull to feel neglect," Strang recalled that he spent "long weary days ... upon the floor, thinking, thinking, thinking ... my mind wandered over fields that old men shrink from, seeking rest and finding none till darkness gathered thick around and I burst into tears."[11][12] He studied works by Thomas Paine and the Comte de Volney,[7] whose book Les Ruines exerted a significant influence on the future prophet.[13][better source needed]

As a youth, Strang kept a rather profound personal diary, written partly in a secret code that was not deciphered until over one hundred years after it was authored. This journal contains Strang's musings on a variety of topics, including a sense that he was called to be a significant world leader the likes of Caesar or Napoleon and his regret that by age nineteen, he had not yet become a general or member of the state legislature, which he saw as being essential by that point in his life to his quest to be someone of importance.[14] However, Strang's diary reveals a heartfelt desire to be of service to his fellow man, together with agonized frustration at not knowing how he might do so as a penniless, unknown youth from upstate New York.[citation needed]

At age twelve, Strang was baptized a Baptist. He did not wish to follow his father's calling as a farmer, so he took up the study of law. Strang was admitted to the bar in New York at age 23 and later at other places where he resided. He became county Postmaster and edited a local newspaper, the Randolph Herald.[15][better source needed] Later, in the midst of his myriad duties on Beaver Island, he would find time to found and publish the Daily Northern Islander, the first newspaper in northern Michigan.[16][better source needed]

Strang, who once described himself as a "cool philosopher"[7] and a freethinker, became a Baptist minister but left in February 1844 to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He quickly found favor with Joseph Smith, though they had known each other only a short time, and was baptized personally by him on February 25, 1844.[17][better source needed][18][non-primary source needed] On March 3 of that year he was ordained an Elder by Joseph's brother Hyrum and sent forthwith at Smith's request to Wisconsin, to establish a Mormon stake at Voree. Shortly after Strang's departure, Joseph Smith was murdered by an anti-Mormon mob in Carthage, Illinois.[citation needed]

Succession claim and notable early allies

[edit]

After Smith's death, Strang claimed the right to lead the Latter Day Saints, but he was not the only claimant to Smith's prophetic mantle. His most significant rivals were Brigham Young, president of Smith's Twelve Apostles, and Sidney Rigdon, a member of Smith's First Presidency. A power struggle ensued, during which Young quickly disposed of Rigdon in a Nauvoo debate. Young would reject offers to debate with Strang for the next three years before leading his followers to Utah while Rigdon led a smaller group to Pennsylvania. As a newcomer to the faith[19] Strang did not possess the name recognition, or a more prominent calling like his rivals, so his prospects of assuming Smith's prophetic mantle appeared shaky at first. But this did not dissuade him. Though the Quorum of Twelve quickly published a notice in the Times and Seasons of Strang's excommunication,[20][better source needed] Strang insisted that the laws of the church prevented excommunication without a trial. He equally asserted that the Twelve had no right to sit in judgment on him, as he was the lawful church president.[21] He began to attract several Mormon luminaries to his side, including Smith's brother William Smith (an Apostle in Smith's church), Smith's mother Lucy Mack Smith, and William Marks, president of the Nauvoo Stake.[citation needed]

Strang rested his claim to leadership on an ordination by an angel at the very moment Joseph Smith died (similar to the ordination of Smith), requirements that he claimed were set forth in the Doctrine and Covenants that the President had to be appointed by revelation and ordained by angels, and a "Letter of Appointment" from Smith, carrying a legitimate Nauvoo postmark. This letter was dated June 18, 1844, just nine days before Smith's death.[19] Smith and Strang were some 225 miles (362 km) apart at the time,[19] Strang offered witnesses to affirm that he had made his announcement before news of Smith's demise was publicly available.[22][non-primary source needed] Strang's letter is held today by Yale University. Every aspect of the letter has been disputed by opposing factions, including the postmark and the signature [23][24][better source needed] however the postmark is genuine and at least one firm (Tyrell and Doud) hired to analyse the document and compare it to Smith's known letters concluded that it was likely to have been authored by Smith. They concluded "A brief observation of these four documents indicates that the education and word usage was consistent with the theory that all four documents were authored by one individual."[25][independent source needed]

There have been several conflicting claims about the authenticity of the letter. One disaffected member of Strang's church said they received a confession from Strang's law partner, C. P. Barnes, that he had fabricated the Letter of Appointment and the Voree Plates.[26] Another member of the Brighamites stated years after Strang's death to have forged the letter himself and mailed it to Strang as a prank.[citation needed] There are no reliable firsthand statements, however, by witnesses or insiders that question the validity of the letter.[citation needed]

Strang's letter convinced several eminent Mormons of his claims, including Book of Mormon witnesses John and David Whitmer, Martin Harris, and Hiram Page.[c] In addition, apostles John E. Page, William E. McLellin, and William Smith,[d] together with Nauvoo Stake President William Marks, and Bishop George Miller,[e] accepted Strang. Joseph Smith's mother, Lucy Mack Smith, and three of his sisters accepted Strang's claims. According to the Voree Herald, Strang's newspaper, Lucy Smith wrote to one Reuben Hedlock: "I am satisfied that Joseph appointed J.J. Strang. It is verily so."[27][independent source needed] According to Joseph Smith's brother William, all of his family (except for Hyrum and Samuel Smith's widows), endorsed Strang.[27][independent source needed]

Also championing Strang was John C. Bennett, a physician and libertine who had a tumultuous career as Joseph Smith's Assistant President and mayor of Nauvoo. Invited by Strang to join him in Voree,[28][better source needed] Bennett was instrumental in establishing a so-called "Halcyon Order of the Illuminati" there, with Strang as its "Imperial Primate."[7] Eventually, as in Nauvoo, Bennett fell into disfavor with the church and Strang expelled him in 1847.[29][better source needed] His "order" fell by the wayside and has no role in Strangism today, though it did lead to conflict between Strang and some of his associates.[citation needed]

From monogamist to polygamist

[edit]This section contains an excessive amount of intricate detail. (April 2025) |

About 12,000 Latter Day Saints ultimately accepted Strang's claims.[30] A second "Stake of Zion" was established on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan, where Strang moved his church headquarters in 1848. Strang's church had a high turnover rate, with many of his initial adherents, including all of those listed above (with the exception of George Miller, who remained loyal to Strang until death), leaving the church before his demise. John E. Page departed in July 1849, accusing Strang of dictatorial tendencies and concurring with Bennett's furtive "Illuminati" order.[31] Martin Harris had broken with Strang by January 1847,[32] after a failed mission to England. Hiram Page and the Whitmers also left around this time.[citation needed]

Many defections, however, were due to Strang's seemingly abrupt "about-face" on the turbulent subject of polygamy. Vehemently opposed to the practice at first,[33][better source needed] Strang reversed course in 1849 and became one of its strongest advocates, marrying five wives (including his original spouse, Mary) and fathering fourteen children. Since many of his early disciples viewed him as a monogamous counterweight to Brigham Young's polygamous version of Mormonism, Strang's decision to embrace plural marriage proved costly both to him and his organization. Strang defended his new tenet by claiming that, far from enslaving or demeaning women, polygamy would liberate and "elevate" them by allowing them to choose the best possible mate based upon any factors which were deemed important by them. Rather than being forced to wed "corrupt and degraded sires" due to the scarcity of more suitable men, a woman could marry the man who she believed was most compatible to her, the best candidate to father her children and give her the finest possible life, even if he had multiple wives.[34][non-primary source needed]

At the time of his death, all four of Strang's current wives were pregnant, and he had four posthumous children.

| Wife | Marriage | Age | Children together | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bride | Groom | |||

| Mary Abigail Content Perce 1818–1880 |

m. Nov 20, 1836 sep. May 1851 |

18 | 23 |

|

| Elvira Eliza Field 1830–1910 |

m. July 13, 1849 | 19 | 36 |

|

| Elizabeth "Betsy" McNutt (1820–1897) |

m. January 19, 1852 | 31 | 38 |

|

| Sarah Adelia "Delia" Wright 1837–1923 |

m. July 15, 1855 | 17 | 42 | James Phineas Strang 1856–1937 |

| Phoebe Wright 1836–1914 |

m. October 27, 1855 | 19 | 42 | Eugenia Jesse 1856–1936 |

Strang and his first wife Mary Perce separated in May 1851, though they remained legally married until Strang's death.[36][better source needed] His second wife, Elvira Eliza Field disguised herself at first as "Charlie J. Douglas," Strang's purported nephew, before revealing her true identity in 1850. Ironically, decades after Strang's death, Strang's fourth wife, Sarah Adelia Wright, divorced her second husband, Dr. Wing, due to Wing's interest in polygamy.[37][better source needed] Strang's last wife was Phoebe Wright, cousin to Sarah.[citation needed]

Sarah Wright described Strang as "a very mild-spoken, kind man to his family, although his word was law." She wrote that while each wife had her own bedroom, they shared meals and devotional time together with Strang and life in their household was "as pleasant as possible."[7][36][better source needed] On the other hand, Strang and Phoebe Wright's daughter, Eugenia, wrote in 1936 that after only eight months of marriage, her mother had "begun to feel dissatisfied with polygamy, though she loved him [Strang] devotedly all her life."[38][better source needed]

Theology

[edit]

Publications

[edit]Like Joseph Smith, James Strang reported numerous visions, unearthed and translated allegedly ancient metal plates using what he said was the Biblical Urim and Thummim, and claimed to have restored long-lost spiritual knowledge to humankind. Like Smith, he presented witnesses to authenticate the records he claimed to have received.[39] Unlike Smith, however, Strang offered his plates to the public for examination. The non-Mormon Christopher Sholes—inventor of the typewriter and editor of a local newspaper—perused Strang's "Voree Plates", a minuscule brass chronicle Strang said he had been led to by a vision in 1845.[40] Sholes offered no opinion on Strang's find, but described the prophet as "honest and earnest" and opined that his followers ranked "among the most honest and intelligent men in the neighborhood."[41][better source needed] Strang published his translation of these plates as the "Voree Record," purporting to be the last testament of Rajah Manchou of Vorito, who had lived in the area centuries earlier and wished to leave a brief statement for posterity.[citation needed] The Voree Plates disappeared around 1900, and their current whereabouts are unknown.[40][independent source needed]

Strang also claimed to have translated a portion of the "Plates of Laban" described in the Book of Mormon.[42][citation needed] This translation was published in 1851 as the Book of the Law of the Lord, said to be selected from the original Law given to Moses and mentioned in 2 Chronicles 34:14–15.[43][better source needed] Republished in 1856, expanded with inspired notes and commentary, this book served as the constitution for Strang's spiritual kingdom on Beaver Island, and is still accepted as scripture by Strangites. One distinctive feature (besides its overtly monarchial tone) is its restoration of a "missing" commandment to the Decalogue: "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself." Strang insisted that versions of the Decalogue found in Bibles used by other churches—including other Latter Day Saint churches—contain only nine commandments, not ten.[44][non-primary source needed]

Strang received several other revelations, which while never formally added to his church's Doctrine and Covenants, are nevertheless accepted as scripture by his followers.[45][independent source needed] These concerned, among other things, Baptism for the Dead, the building of a temple in Voree, the standing of Sidney Rigdon, and an invitation for Joseph Smith III, eldest son of Joseph Smith, to take a position as Counselor in Strang's First Presidency. "Young Joseph" never accepted this calling and refused to have anything to do with Strang's organization. Strang also authored The Diamond, an attack on the claims of Sidney Rigdon and Brigham Young, and The Prophetic Controversy, ostensibly for Mrs. Martha Coray, co-author with Lucy Mack Smith of The History of Joseph Smith by His Mother. Coray, a partisan of Brigham Young's, had challenged "the vain usurper" to provide convincing evidence of his claims,[46][non-primary source needed] and Strang obliged in this open letter addressed to her. Coray's reaction has not been preserved.[citation needed]

Distinctive dogmas

[edit]Some of Strang's teachings differed substantially from those of other Latter Day Saint leaders, including Joseph Smith. For instance, Strang rejected the traditional Christian doctrines of the Trinity and the Virgin Birth of Jesus Christ, together with the Mormon doctrine of the "plurality of gods." A monotheist, he insisted that there was only one eternal God in all the universe, Father, and that "progression to godhood" (a doctrine allegedly taught by Joseph Smith toward the end of his life) was impossible. God had always been God, said Strang, and He was only one Person, not three persons, according to the doctrine of the traditional Christian Trinity.[47] Jesus Christ was presented as the natural-born son of Mary and Joseph, who was chosen from before all time to be the Savior of mankind but he had to be born as an ordinary mortal from two human parents (rather than being the offspring of either the Father or the Holy Spirit) in order to fulfill his Messianic role.[48] In essence, Strang claimed that the earthly Christ was "adopted" as God's son at birth, and he was fully revealed to be such during the Transfiguration.[49] After proving himself to God by living a perfectly sinless life, he was enabled to provide an acceptable sacrifice for the sins of men, prior to his resurrection and ascension.[50]

Furthermore, Strang denied the belief that God could do all things, and he insisted that some things were as impossible for Him as for us.[51] Thus, he saw no essential conflict between science and religion, and while he never openly championed evolution, he did state that God's ability to use His power was limited by the matter which He was working with and it was also limited by the eons of time which were required to "organize" and shape it.[52] Strang spoke glowingly about a future generation of people who would "make religion a science," to be "studied by as exact rules as mathematicks." "The mouth of the Seer will be opened," he prophesied, "and the whole earth enlightened."[53]

Musing at length on the nature of sin and evil, Strang wrote that of all of the things that God could give to man, He could never give him experience.[54] Thus, if "free agency" was real, said Strang, humanity must be given the opportunity to fail and learn from its own mistakes. The ultimate goal for each human being was to willingly conform oneself to the "revealed character" of God in every respect, preferring to do good rather than preferring to do evil not out of fear of punishment and not out of any desire for rewards, but preferring to do good solely "on account of the innate loveliness of undefiled goodness; of pure unalloyed holiness."[55]

Practices

[edit]Strang strongly believed in the sanctity of the seventh-day Sabbath, and he enjoined it in lieu of Sunday;[56] the Strangite church continues to observe this tradition. He advocated baptism for the dead, and practiced it to a limited extent in Voree as well as on Beaver Island. He also introduced animal sacrifice–not as atonement for sin, but as a part of Strangite celebration rituals.[57] Animal sacrifices and baptisms for the dead are not currently practiced by the Strangite organization, but belief in each is still required by it. Strang attempted to construct a temple in Voree, but he was prevented from completing its construction due to the poverty and lack of cooperation which existed among his followers.[58] No "endowment" rituals which are comparable to those in the Utah LDS and the Cutlerite churches appear to have existed among his followers.[59] Eternal marriage formed a part of Strang's teaching, but he did not require it to be performed in a temple (as is the case in the LDS church). Thus, such marriages are still contracted in Strang's church in the absence of any Strangite temple or any "endowment" ceremony. Alcohol, tobacco, coffee and tea were all prohibited, just as they were in many other Latter Day Saint denominations. Polygamy is no longer practiced by Strang's followers, but belief in its correctness is still affirmed by them.[59]

Strang allowed women to hold the Priesthood offices of Priest and Teacher, unique among all Latter Day Saint factions during his lifetime.[60] He welcomed African Americans into his church, and he ordained at least two of them to its eldership.[61] Strang also mandated the conservation of land and resources, requiring the building of parks and the retention of large forests in his kingdom.[62] He wrote an eloquent refutation of the "Solomon Spalding theory" of the Book of Mormon's authorship,[63] and defended the ministry and teachings of Joseph Smith.[citation needed]

Coronation and troubled reign on Beaver Island

[edit]Strang claimed that he was required to occupy the office of king as it is described in the Book of the Law of the Lord.[64][non-primary source needed] He insisted that this authority was incumbent upon all holders of the prophetic office from the beginning of time,[65] in similar fashion to Smith, who was secretly crowned as "king" of the Kingdom of God[66] before his murder.[6][better source needed] Strang was accordingly crowned in 1850 by his counselor and Prime Minister, George J. Adams. About 300 people witnessed his coronation, for which he wore a bright red flannel robe which was topped by a white collar with black speckles. His crown was made of tin, rather than gold, and it is described in one account as being "a shiny metal ring with a cluster of glass stars in the front."[7] Strang also sported a breastplate and carried a wooden scepter.[67] His reign lasted six years, and the date of his coronation, July 8, is still mandated as one of the two most important dates in the Strangite church year (the other being April 6, the anniversary of the founding of Joseph Smith's church).[68][non-primary source needed]

Strang never claimed to be the king of Beaver Island itself, nor did he claim to be the king of any other geographical entity. Instead, he claimed to be king of his church, which he considered the true "Kingdom of God" which was prophesied in Scripture and destined to spread itself over all the earth.[69][better source needed] Nor did Strang ever say that his "kingdom" supplanted United States sovereignty over Beaver Island. However, since his sect was the main religious body on the isle, claiming the allegiance of most of its inhabitants, Strang often asserted his authority on Beaver, even over non-Strangites—a practice which ultimately caused him and his followers a great deal of grief. Furthermore, he and many of his disciples were accused of forcibly appropriating property and revenue on the island, a practice which earned him few friends among the non-Mormon "gentiles."[citation needed]

On the other hand, Strang and his people lived in apprehension of what their non-member neighbors might do next. Some Strangites were beaten up while they were going to the post office in order to collect their mail,[70][better source needed] and some of their homes were robbed and even seized by "gentiles" while Strangite men were away.[71][better source needed] On July 4, 1850, a drunken mob of fishermen vowed to kill the "Mormons" or drive them out, only to be awed into submission when Strang fired a cannon (which he had secretly acquired) at them.[72][non-primary source needed] Competition for business and jobs added to tensions on the island, as did the increasing Strangite monopoly on local government, made sure after Beaver and adjacent islands were first attached to Emmet County in 1853, then later organized into their own insular county of Manitou in 1855.[citation needed]

As a result of his coronation, along with lurid tales which were being spread by George Adams (who had been excommunicated by Strang a few months after the ceremony), Strang was accused of treason, counterfeiting, trespassing on government land, and theft, along with other crimes. He was brought to trial in Detroit, Michigan, after President Millard Fillmore ordered US District Attorney George Bates to investigate the rumors about Strang and his colony.[7] Strang's successful trial defense brought him considerable favorable press, which he used as leverage when he ran for, and won, a seat on the Michigan state legislature as a Democrat in 1853. Facing a determined effort to deny him this seat due to the hostility of his enemies, he was permitted to address the legislature in his defense, after which the Michigan House of Representatives voted twice (first unanimously, then a second time by a 49–11 margin) to allow "King Strang" to join them.[73][better source needed]

In the 1853 legislative session, Strang introduced ten bills, five of which passed.[74][better source needed] The Detroit Advertiser, on February 10, 1853, wrote of Strang: "Mr. Strang's course as a member of the present Legislature, has disarmed much of the prejudices which have previously surrounded him. Whatever may be said or thought of the peculiar sect of which he is the local head, I take pleasure in stating that throughout this session he has conducted himself with the degree of decorum and propriety which have been equaled by his industry, sagacity, good temper, apparent regard for the true interests of the people, and the obligations of his official oath."[75] He was reelected in 1855, and did much to organize the upper portion of Michigan's lower peninsula into counties and townships. Strang ardently fought the illegal practice of trading liquor to local Native American tribes due to the common practice of selling them diluted liquor mixed with various contaminants at a high price.[76][non-primary source needed][77][better source needed] This made him many enemies among those non-Strangite residents of Beaver and nearby Mackinac Island who profited mightily from this illicit trade.[citation needed]

Assassination

[edit]James Strang had problems with excommunicated or disaffected members who often became anti-Mormons and/or even conspired against him. One of the latter, Thomas Bedford, who had been flogged for engaging in adultery with another member's wife, blamed Strang for the flogging and sought revenge.[78][better source needed] Another, Hezekiah D. McCulloch, had been excommunicated for drunkenness and other alleged misdeeds, after previously enjoying Strang's favor and several high offices in local government. These men conspired against Strang along with the Mormons' enemies who were living in Mackinac, two of whom were Alexander Wentworth and Dr. J. Atkyn. Pistols were procured, and the four conspirators began several days of target practice while they finalized the details of their murderous plan.[79]

Although Strang apparently knew that Bedford and the others were gunning for him, he openly challenged them in his newspaper, The Northern Islander, writing, "We laugh with bitter scorn at all these threats," just days before his murder.[7] Strang refused to employ a bodyguard or carry a firearm or any other type of weapon.[80]

On Monday, June 16, 1856, Strang was waylaid around 7:00 PM on the dock at the harbor of St. James, the chief city on Beaver Island, by Wentworth and Bedford, who shot him in the back.

Strang was hit three times: one bullet grazed his head, another bullet lodged in his cheek and a third bullet lodged in his spine, paralyzing him from the waist down.[81] One of the assassins then pistol-whipped the victim before running aboard the nearby vessel with his companion, where both claimed sanctuary.[82] Some accused Captain McBlair of the USS Michigan of being complicit in, or at least of having foreknowledge of, the assassination plot, though no hard evidence to support their accusation was ever forthcoming.[83][better source needed][84][better source needed] The "King of Beaver Island" was taken to Voree, where he lived for three weeks, dying on July 9, 1856, at the age of 43.[85] After refusing to deliver Bedford and Wentworth to the local Sheriff of Mackinac County,[86] Julius Granger, McBlair transported them to Mackinac Island. Once on the island Sheriff Granger first held them in an unlocked jail cell at the ‘urging’ of the citizenry and then moved to a boarding house he was keeping, Grove House. Three days later they were given a ‘mock trial’ where the justice charged them $1.25 a piece for court costs, then released them where they were feted by the local citizenry.[7][87] None of those involved received punishment for their alleged crimes Dr. Hezekiah D. McCulloch and Dr. J. Atkyn, with Thomas Bedford living until 1889 and Alexander Wentworth living until 1863.[citation needed]

Death of a kingdom

[edit]While Strang lingered on his deathbed in Voree, his enemies in Michigan were determined to extinguish his Beaver Island kingdom. On July 5, 1856, on what Michigan historian Byron M. Cutcheon later called "the most disgraceful day in Michigan's history,"[7] a group of non-Mormons from Mackinac and elsewhere forcibly evicted every Strangite from Beaver Island. Strang's subjects on the island—approximately 2,600 persons[7]—were herded onto hastily commandeered steamers, most after being robbed of their money and other personal possessions, and unceremoniously dumped onto docks along the shores of Lake Michigan. A few of them moved back to Voree, while the rest scattered across the country.[citation needed]

Strang refused to appoint a successor, telling his apostles to take care of their families as best they could, and await divine instruction.[88][better source needed] While his supporters endeavored to keep his church alive, Strang's unique dogma which required his successor to be ordained by angels[89][non-primary source needed] made his church unappealing to Latter Day Saints who were expecting to be led by a prophet. Lorenzo Dow Hickey, the last of Strang's apostles, emerged as an ad-hoc leader until his death in 1897, followed by Wingfield W. Watson, a High Priest in Strang's organization (until he died in 1922). However, neither of these men ever claimed Strang's office or authority.[f]

Left without a prophet to guide them, most of Strang's followers (including all of his wives)[90][better source needed] departed from his church in the years after his murder. Most of them later joined the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, which was established in 1860.[g] However, a few Latter Day Saints continue to carry on Strang's mission. Strang's last and most important revelation, The Book of the Law of the Lord[91] states that a prophet president is "...only necessary for the establishment of the rest of God, and bringing everlasting righteousness on earth. A lesser degree of the Priesthood has frequently stood at the head of the people of God on earth" (p. 251). Consequently, instead of believing that Strang's demise and his refusal to appoint a successor are failures, they believe that they are maintaining the pure faith and awaiting the appearance of a new successor who will take the place of their fallen founders. They believe that their position is bolstered by revelations which were given by Smith and Strang in which they stated that the condemnation of the church is prophetic and a sign of general apostasy.[citation needed]

Today, there are several groups and individual Strangite disciples who operate autonomously. One of these groups is a corporate church which is led by a Presiding High Priest, Bill Shepard, who claims that he does not have Joseph Smith or James Strang's authority or priesthood office[citation needed]. Another group, which is led by Samuel West, claims that the first faction is in error, and it also claims that by incorporating in 1961, it lost its identity as a faithful continuation of Strang's organization. This second group claims that it is the sole true remnant of James Strang's church.[h][92] Missionary work is no longer emphasized by Strangites (as it is by the LDS and many other Latter Day Saint sects), because they tend to believe that after the murder of three prophets (Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith and James Strang) God closed His dispensation to the "gentiles" of the West.[93][better source needed] Consequently, Strang's church has continued to dwindle until the present day. The current membership of the corporate church comprises around 300 persons, while the Samuel West group claims to have several thousand members in the US and Africa.[94]

While proving to be a key player in the 1844 succession struggle, Strang's long-term influence on the Latter Day Saint movement was minimal. His doctrinal innovations had little impact outside his church, and he was largely ignored until recent historians began to reexamine his life and career. Even the county (Manitou) which he had fought to establish was abolished by the Michigan legislature in 1895, removing the last tangible remnant of Strang's temporal empire.[95][better source needed] Of all of his efforts, Strang's most vital (albeit unintended) one was his contribution to the Latter Day Saint religion which turned out to provide some of the impetus behind the creation of the Reorganized Church, which became a major rival of the Utah-based LDS Church and other Latter Day Saint groups—including his own.[citation needed]

Selected works

[edit]- Strang, Mark, ed. (1961). The Diary of James J. Strang: Deciphered, Transcribed, Introduced, and Annotated. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Strang, James J. (1854a, Reprinted 2005). Ancient and modern Michilimackinac, including an account of the controversy between Mackinac and the Mormons. Reprint by the University of Michigan Library. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- Strang, James J. (1848). The Diamond: Being the Law of Prophetic Succession and a Defense of the Calling of James J. Strang as Successor to Joseph Smith. Voree, Wisconsin. Retrieved on 2007-11-03.

- Strang, James J. (1854b). The Prophetic Controversy: A Letter from James Strang to Mrs. Corey. St. James, Michigan. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- Strang, James J. (1856). Book of the Law of the Lord, Being a Translation From the Egyptian of the Law Given to Moses in Sinai. St. James: Royal Press. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b The Strangites use no hyphen in their church title and capitalize the "D" in "Day", just as was done in Joseph Smith's church.

- ^ Strangites still use these terms today, as do members of some other Latter Day Saint groups.

- ^ David Whitmer and Martin Harris, two of the Three Witnesses, and Hiram Page and John Whitmer of the Eight Witnesses.

- ^ John Page and William Smith were apostles at Smith's death; William M'Lellin had previously been an apostle, but was excommunicated in 1838.

- ^ George Miller, who is mentioned in the LDS Doctrine & Covenants section 124: verses 20, 62 and 70.

- ^ No apostles currently remain in Strang's organization, because all Strangite apostles must be appointed by revelation. The highest current office in Strang's church is that of High Priest (in the "incorporated" faction) or that of Elder (in the other).

- ^ This organization is now called the Community of Christ. It remains the second-largest church in the Latter Day Saint movement.

- ^ The corporate church has a website: http://www.ldsstrangite.com/; "unincorporated" Strangites have three websites: http://www.strangite.org and http://mormonbeliefs.com and http://www.strangite.blogspot.com.

Citations

[edit]- ^ (August 12, 1847). Voree Herald as quoted in Fitzpatrick, pp. 74–5. See also Apostle John E. Page at this same source, on his conversations with Strang on the subject.

- ^ "History and Succession Archived 2012-12-28 at archive.today". Strangite.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ "See "Church membership: 1830–2006"".

- ^ Statement by Nauvoo Stake President William Marks, Zion's Harbinger and Banemeey's Organ, July 1853, pg. 53.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 168–76.

- ^ a b "Strang, the King Archived 2007-09-25 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Weeks, Robert P. (June 1970). "For His Was the Kingdom, and the Power, and the Glory ... Briefly". American Heritage. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- ^ "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints Archived 2007-09-25 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Rodgers, Bradley A. (1996). Guardian of the Great Lakes: The U.S. Paddle Frigate Michigan. University of Michigan Press. p. 60. ISBN 0472066072.

- ^ Post, Warren. "History of James Strang: The Birth and Parentage of the Prophet James". StrangStudies.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ a b "Strang, the Man Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-31

- ^ Legler, Henry Eduard (1897). "A Moses of the Mormons: Strang's City of Refuge and Island Kingdom". Parkman Club Publications (15–16): 150.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Strang, Mark. (1961). The Diary of James J. Strang: Deciphered, Transcribed, Introduced, and Annotated. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. Entry for March 21, 1832. The diary was deciphered by Strang's grandson Mark Strang, a banker in Long Beach, California.

- ^ Jensen, Robin (2005). Gleaning the Harvest: Strangite Missionary Work 1846–1850, p. 32. Retrieved on 2016-02-09.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 208.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 27.

- ^ Greene, John P. (Nauvoo City Marshal in 1844). "150 people who each knew more about Joseph Smith than anyone alive today." Strangite.org, item 48. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ a b c Norton 2003, p. 3

- ^ "Times and Seasons Volume 5, Number 16". www.centerplace.org.

- ^ "Uncle Dale's Old Mormon Articles: Iowa, Wisc. & Minn.: Strang: 1848-51". www.sidneyrigdon.com.

- ^ Strang 1854b, p. 23.

- ^ Quinn, p. 210, although the postmark has been proven to be legitimate. See also Eberstadt, Charles, "A Letter That Founded a Kingdom," Autograph Collectors' Journal (October, 1950): 3–8.

- ^ Jensen, p. 6, note 17.

- ^ Shepard, William (1977). James J. Strang: Teachings of a Mormon Prophet. Burlington, WI: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. pp. 261–262.

- ^ Nelson-Seawright, J. (October 27, 2006). "The Prophet Jesse James". ByCommonConsent.com. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- ^ a b (Nauvoo, 11 May 1846). "Opinions of the Smith Family". Voree Herald I (6). Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

a: Letter of Lucy Smith to Reuben Hedlock.

b: Letter of William Smith to Reuben Hedlock. - ^ Fitzpatrick, pp. 146–47.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 151.

- ^ "History and Succession Archived 2012-12-28 at archive.today". Strangite.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Sillito, Chapter 2.

- ^ Sketch of the Life of Martin Harris Archived 2007-07-20 at the Wayback Machine BOAP.org. Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ^ (August 12, 1847). Voree Herald as quoted in Fitzpatrick, pp. 74–75. See also Apostle John E. Page at this same source, on his conversations with Strang on the subject.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 318–28.

- ^ Speek, Vickie Cleverley (2006). God Has Made Us a Kingdom. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. pp. 375–377. ISBN 9781560851929.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, p. 82.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 127.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 84.

- ^ Weeks, pp. iv, 250.

- ^ a b A drawing of these plates, with translation and testimony of their discovery, may be found at James J. Strang. (1845). "The Record of Rajah Manchou of Vorito. Archived 2012-09-17 at archive.today" Strangite.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 36.

- ^ I Nephi 3:1 – 5:22 (Book of Mormon).

- ^ "Book of the Law Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 38–46.

- ^ http://www.strangite.org/Reveal.htm. Archived 2024-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Strang 1854b, p. 1.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 47–63.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 157–58, note 9.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 165–66.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 155–58.

- ^ Strang 1856, p. 150.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 150–51.

- ^ Strang 1856, p. 85. Spelling of "mathematicks" as in original.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Strang 1856, p. 155.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 106–09, 293–95.

- ^ "Temple Locations". Strangite.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ a b "Women/Marriage Archived 2013-01-13 at archive.today". Strangite.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 198–200, 227.

- ^ "African-Americans". Strangite.org. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 286–87.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 251–68.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 168–80.

- ^ "Church History Volume 3, Chapter 2". www.centerplace.org.

- ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005), Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, New York: Knopf, ISBN 1-4000-4270-4

- ^ This sceptre is preserved in the Archives vault of the Community of Christ church in Independence, Missouri. See Cemetourism: Alpheus Cutler, in the paragraph about Alpheus Cutler's sword, which mentions Strang's sceptre as being kept with it in the CofC vault.

- ^ Strang 1856, p. 293.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 199.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 86.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 96.

- ^ Strang 1854a, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 101.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 100.

- ^ (February 10, 1853). Detroit Advertiser. Excerpt in "Mormon Persecution Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Strang 1854a, pp. 15–17

- ^ Fitzpatrick, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 110.

- ^ "Apostle Post on James' Death Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ (August 14, 1851). Northern Islander as quoted in Fitzpatrick, p. 97.

- ^ Noord, Roger Van (1997). Assassination of a Michigan King: The Life of James Jesse Strang. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08454-8.

- ^ (Friday, June 20, 1856). Daily Northern Islander. Excerpt in "Murderous Assault Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, pp. 113, 211.

- ^ "Apostle Chidester Announces James’ Death Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Turner, John G. (September 25, 2012). Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet. Harvard University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-674-06731-8.

- ^ Northern Islander, June 20, 1856.

- ^ (2002-10-10). "The Man who shot Strang." BeaverBeacon.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ "Kingdom with a Dominion Archived 2007-09-25 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Strang 1856, pp. 163–66.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, p. 125.

- ^ The first edition of this book was published in 1850, without notes. A second edition, with numerous notes and other material, was still unbound and on the press at the time of his assassination.

- ^ "The 1961 Strangite Split Archived 2007-09-25 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com.

- ^ "Mormonism: time of the Gentiles ended Archived 2007-09-25 at the Wayback Machine". MormonBeliefs.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ "43,941 adherent statistic citations: membership and geography data for 4,300+ religions, churches, tribes, etc." Adherents.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-28.

- ^ History of Northern Michigan, pg. 100.

References

[edit]- Fitzpatrick, Doyle C. (1970). The King Strang Story: A Vindication of James J, Strang, the Beaver Island Mormon King. National Heritage. ISBN 0-685-57226-9.[better source needed]

- Jensen, Robin Scott (2005). Gleaning the Harvest: Strangite Missionary Work, 1846–1850 (MA thesis). Brigham Young University.

- Norton, William (2003). "Competing Identities and Contested Places: Mormons in Nauvoo and Voree". Journal of Cultural Geography. 21 (1): 95–119. doi:10.1080/08873630309478268. S2CID 144847696.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1994). The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power. Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-056-6.

- Speek, Vickie Cleverly (2006). God Has Made Us a Kingdom: James Strang and the Midwest Mormons. Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-192-9.

Further references

[edit]- Beshears, Kyle (Spring–Summer 2023). "'In Love and Union': The Writings of Mr. Charles J. Douglass, Secret Plural Wife of a Mormon King". John Whitmer Historical Association. 43 (1): 41–54.

- Blythe, Christopher James (June 2014). "The Coronation of James J. Strang and the Making of Beaver Island Mormonism". Communal Societies: Journal of the Communal Studies Association. 34 (1) – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- DeRogatis, Amy (Spring–Summer 2023). "Intimate Exposure: The Charley Douglass Daguerreotype and American Religious History". John Whitmer Historical Association Journal. 43 (1): 20–40.

- Faber, Don (2016). James Jesse Strang: The Rise and Fall of Michigan's Mormon King. University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.6963838. ISBN 9780472052899.

- Foster, Lawrence (June 1981). "James J. Strang: The Prophet Who Failed". Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture. 50 (2): 182–192. doi:10.2307/3166882. JSTOR 3166882. S2CID 162192346.

- Harvey, Miles (2020). The King of Confidence: A Tale of Utopian Dreamers, Frontier Schemers, True Believers, False Prophets, and the Murder of an American Monarch. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0316463591.

- Jensen, Robin Scott (2007). "Mormons Seeking Mormonism: Strangite Success and the Conceptualization of Mormon Ideology, 1844–50". In Bringhurst, Newell G.; Hamer, John C. (eds.). Scattering of the Saints: Schism Within Mormonism. John Whitmer Books. ISBN 9781934901021.

- Quist, John (1989). "Polygamy Among James Strang and His Followers". John Whitmer Historical Association Journal. 9: 31–48. JSTOR 43200832.

- Silitto, John and Staker, Susan (eds.). (2002). Mormon Mavericks: Essays on Dissenters. Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-154-6.

- van Noord, Roger (1988). King of Beaver Island: The Life and Assassination of James Jesse Strang. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01472-3.

- van Noord, Roger (1997). Assassination of a Michigan King: The Life of James Jesse Strang. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472084548.

External links

[edit] Media related to James Strang at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James Strang at Wikimedia Commons- Clarke Historical Library: Strangite Mormons – Brief biography from Central Michigan University, which has a collection of letters and diaries written by Strang and his followers.

- A True History of the Rise of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, of the Restoration of the Holy Priesthood and the Late Discovery of Ancient American Records; MSS SC 756; 20th Century Western and Mormon Manuscripts; L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- James Jesse Strang Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

James Strang

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Conversion to Mormonism

Childhood and Education in New York

James Jesse Strang was born on March 21, 1813, in Scipio, Cayuga County, New York, to Thomas Strang, a farmer, and Mary James Strang.[3][4] The family resided on a modest farm, and Strang was the second of three children.[3] His parents, originating from Saratoga and Washington Counties, later moved the family to Chautauqua County in western New York, where Strang spent much of his formative years.[5] In childhood, Strang was perceived by contemporaries as mentally deficient, a characterization that concealed his underlying precocious intelligence and restless energy.[6][7] He exhibited early struggles in formal schooling and harbored outsized ambitions, expressing in personal writings by age 19 a frustration at not yet achieving roles such as general or state legislator, and envisioning himself as a figure of historical magnitude akin to Napoleon or Julius Caesar.[5] This period was marked by a compulsive drive for knowledge, channeled into voracious reading rather than conventional academic success.[6] Strang's formal education began with the limited instruction available in rural district schools, followed by a short term at the Fredonia Academy in Chautauqua County, established in 1823.[3][6] These experiences provided basic literacy and arithmetic but did little to temper his self-directed intellectual pursuits, which later extended to legal studies; he was admitted to the New York bar in 1836 after self-study and practical apprenticeship.[6][3]Intellectual Development and Initial Skepticism

Strang demonstrated early intellectual ambition beyond his rural upbringing, pursuing self-directed studies in law after rejecting his father's farming occupation. Lacking formal higher education, he immersed himself in legal texts and gained admission to the New York bar in 1836 at age 23, establishing a foundation for his analytical and argumentative skills.[6] [8] His subsequent roles as a schoolteacher, journalist for local papers, and postmaster in Randolph, New York, further honed his capacity for research, writing, and public discourse, traits evident in his later theological writings and legal defenses of his movement. Raised in a Baptist household and baptized at age 12, Strang soon embraced religious skepticism, aligning with freethinking currents of the era that questioned orthodox Christianity. By age 18, he recorded personal doubts culminating in atheistic conclusions, viewing organized religion as unsupported by evidence and preferring rational inquiry over faith.[9] This phase reflected a broader deistic or materialistic outlook, prioritizing empirical reasoning and self-reliance, which shaped his independent character but left him open to new paradigms if substantiated. His initial encounter with Mormonism in the early 1840s, amid reports of the Nauvoo community's growth, elicited similar scrutiny rather than immediate acceptance. Strang investigated the movement's doctrines and Joseph Smith's prophetic claims through correspondence and printed materials, approaching them as a detached observer skeptical of supernatural assertions.[10] This methodical evaluation, consistent with his legal training, preceded his baptism on February 25, 1844, marking a shift from doubt to conviction after deeming the evidence compelling.[11]Encounter with Mormonism and Baptism

James Jesse Strang, shaped by deistic influences and a skeptical disposition toward established religions, initially encountered Mormonism around 1836 shortly after his marriage but dismissed it amid his broader philosophical doubts.[12] In his early adulthood, while working as a postmaster and newspaper editor in western New York, Strang immersed himself in rationalist texts such as Constantin François de Volney's The Ruins, which critiqued supernatural claims and reinforced his reluctance to embrace sectarian Christianity without empirical warrant.[10] By late 1843, after relocating to Burlington in the Wisconsin Territory to serve as postmaster, Strang acquired a copy of the Book of Mormon and subjected it to rigorous scrutiny, ultimately deeming its historical and doctrinal assertions persuasive enough to prompt a reevaluation of his prior skepticism.[13] Convinced of the book's authenticity through personal study rather than external proselytizing, he resolved to affiliate with the Latter Day Saint movement and traveled approximately 200 miles to Nauvoo, Illinois, arriving in early February 1844.[14] In Nauvoo, Strang met church founder Joseph Smith, who baptized him on February 25, 1844, in the partially constructed baptismal font of the Nauvoo Temple—a site intended for vicarious ordinances but used here for living baptisms amid the city's ongoing temple preparations.[14][13][5] This immersion marked Strang's formal entry into the church, after which he was promptly ordained an elder on March 3, 1844, and tasked with organizing a mission in Wisconsin to gather converts and establish a stake at Voree.[14][5]Rise Within the Latter Day Saint Movement

Relocation to Nauvoo and Association with Joseph Smith

In 1843, Strang relocated from New York to Burlington in the Wisconsin Territory, where he practiced law and engaged with local Mormon converts. Accompanied by Aaron Smith, he undertook an approximately 175-mile journey on foot to Nauvoo, Illinois, the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, arriving in early 1844.[12][5] There, Strang met Joseph Smith, the church's founder and prophet, who personally baptized him into the church circa February 1844 in the unfinished baptismal font of the Nauvoo Temple. Shortly following his baptism, Strang was ordained an elder by church authorities in Nauvoo, marking his rapid integration into the Mormon hierarchy despite his recent conversion.[1][5][15] Strang's association with Smith was limited in duration, as he returned to Wisconsin shortly after his ordination to manage personal affairs, just months before Smith's assassination on June 27, 1844. During his brief stay in Nauvoo, Strang observed Smith's leadership firsthand, including public preaching, and expressed admiration for the prophet's intellectual and spiritual authority, though he held no prominent administrative roles within the church prior to departing.[1][10][16]Roles and Contributions Prior to Smith's Death

James Jesse Strang, a lawyer and former postmaster from Burlington in Wisconsin Territory, traveled to Nauvoo, Illinois, in February 1844 to investigate the Latter Day Saint movement. He was baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by Joseph Smith circa February 25, 1844, in the Nauvoo Temple font.[1][15] Following his baptism, Strang was ordained an elder shortly thereafter, marking his entry into church ministry as a neophyte convert.[1] With his background in law and education, he engaged in initial proselytizing activities, leveraging his rhetorical skills to defend and promote Mormon doctrines among acquaintances in the Midwest.[13] Strang's contributions prior to Joseph Smith's death on June 27, 1844, were limited by the brief four-month span of his active involvement, consisting mainly of returning to Wisconsin to establish local branches and gather converts, including family members and associates, without holding formal administrative roles in Nauvoo.[15] His efforts laid preliminary groundwork for a regional stake of Zion, as later referenced in communications from Smith, though no such organization was formalized before the martyrdom.[1]The Succession Claim

Alleged Letter of Appointment from Joseph Smith

James Strang claimed to have received a letter from Joseph Smith dated June 18, 1844, from Nauvoo, Illinois, which he presented as evidence of his appointment as Smith's successor to lead the Latter Day Saint church if misfortune befell Smith.[14] The document responded to Strang's epistle of May 24, 1844, proposing the establishment of a stake of Zion in Voree, Wisconsin Territory, affirming divine approval through a heavenly messenger and Hyrum Smith's endorsement, and directing Strang to plant the stake there as a gathering place for the saints.[17] It instructed apostles, priests, and elders to proclaim Strang's authority publicly and gather the church under his direction, concluding that Strang would become the "Shepherd, the Stone of Israel" to lead the flock in Smith's stead.[17] Strang stated the letter arrived by mail after Smith's death on June 27, 1844, bearing a postmark dated June 19 from Nauvoo, and he first published it in his 1846 pamphlet The Diamond.[14] He cited witnesses including Aaron Smith, Joseph's cousin, and Edward Whitcomb, who purportedly examined the document and affirmed its validity, while some of Smith's relatives, such as William Smith and Lucy Mack Smith, initially supported Strang's claim partly on the letter's basis.[17] Strang, a former postmaster and attorney with typesetting experience, argued the postmark proved timely dispatch amid the church's June 1844 crises, including Smith's imprisonment.[14] The letter's authenticity has been rejected by most historians. Examination shows the body text in printed lettering inconsistent with Smith's characteristic cursive handwriting, while the signature deviates from verified examples, suggesting tracing.[14] Antiquarian Charles Eberstadt, after analyzing the manuscript, declared it a forgery, a view echoed by Yale University's archival assessment of the signature.[17] Paper stock differences and the absence of corroborating Nauvoo records during Smith's final preoccupied days further undermine its provenance, with scholarly analysis attributing the fabrication to Strang himself to exploit the succession vacuum.[14][18]Discovery of the Voree Plates and Prophetic Validation

In September 1845, following his public assertion of succession to Joseph Smith via an alleged letter of appointment, James Strang reported an angelic visitation at Voree, Wisconsin (near Burlington), which directed him to unearth ancient brass plates as validation of his prophetic authority.[19][20] On September 1, Strang claimed the angel—identified in some accounts as akin to Moroni—revealed the location of the plates buried under an oak tree's roots on a hillside known as the Hill of Promise, and provided a seer stone or Urim and Thummim for translation.[21][2] This event built on a prior vision Strang described in June 1845, positioning the plates as empirical confirmation of divine endorsement amid rival succession claims by figures like Brigham Young.[22] On September 13, 1845, Strang led four witnesses—Nathaniel Miller, Edward McLellin (briefly), Aaron Smith, and George Miller—to the site, where they excavated three small brass plates, each about 2 by 2.5 inches, bound with three rings and inscribed with characters resembling modified Hebrew or Egyptian hieroglyphs.[20][23] The plates, dubbed the Voree Plates or Record of Rajah Manchou of Vorito, were presented as an ancient record from an Asian prince's lost tribe, predating European settlement.[24] Strang restricted direct handling to himself and the witnesses, who later signed testimonies affirming the plates' ancient appearance and the circumstances of discovery, though McLellin soon defected and questioned the authenticity.[25] Strang translated the plates within days using the provided seer instrument, publishing the text in The Voree Herald and later works like The Prophetic Controversy.[26] The translation, spanning about 20 lines, lamented the destruction of an ancient people ("My people are no more. The mighty are fallen"), prophesied Joseph Smith's death as "the forerunner," and heralded a "mighty prophet" to succeed him in translating further records—implicitly Strang himself.[20] It also designated Voree as the divinely appointed gathering place for the Saints, countering migrations to Utah.[27] This discovery served as Strang's primary prophetic validation, mirroring Joseph Smith's golden plates in method and purpose, thereby attracting converts like John C. Bennett and William Smith by fulfilling a purported test of authenticity: producing tangible artifacts akin to biblical precedents.[28] Critics, including mainstream Latter-day Saints, dismissed the plates as a forgery due to their rapid production and linguistic inconsistencies, but Strang's adherents viewed the event as causal proof of his apostolic mantle, enabling recruitment and doctrinal authority until the plates vanished around 1900.[29]Ordination and Recruitment of Key Allies

Strang maintained that an angel ordained him to the office of prophet, seer, and revelator on June 27, 1844, at 5:30 p.m., precisely coinciding with the martyrdom of Joseph Smith over 200 miles away in Carthage, Illinois; this purported event occurred privately without corroborating witnesses, depending entirely on Strang's personal account recorded in his revelations.[30][22] To establish legitimacy amid competing succession claims, Strang actively recruited endorsements from established church authorities by circulating copies of the June 18, 1844, letter purportedly from Smith designating him successor and, later, the translated Voree plates unearthed on September 1, 1845.[17] Prominent recruits included Nauvoo Stake President William Marks and Bishop George Miller, who traveled to Voree, Wisconsin, in December 1844 to scrutinize Strang's documents and the plates' authenticity; both affirmed his prophetic mantle, with Miller defecting from Brigham Young's faction to join Strang's group, providing early organizational structure through his experience as a high councilor. Apostles John E. Page and William Smith—Joseph Smith's younger brother and holder of patriarchal and apostolic offices—likewise aligned with Strang, Page after his June 26, 1846, excommunication from the main body for opposing Young, and Smith offering familial ties to Smith's legacy despite his own prior inconsistencies in allegiance. These alliances conferred doctrinal weight, as Page and Smith represented surviving quorum members whose support implied ratification of Strang's angelic ordination via apostolic confirmation, though both later departed by 1847 amid internal disputes.[31][32] Strang's recruitment efforts yielded a core cadre numbering around 2,500 adherents by 1846, concentrated in eastern branches like Kirtland, Ohio, where skepticism toward Young's westward exodus facilitated conversions; key allies facilitated missionary outreach, with Page dispatched to proselytize in Canada and the East, leveraging their prior stature to challenge rival claimants like Young and Sidney Rigdon. Empirical assessments of source documents, including handwriting analysis of the appointment letter, have yielded mixed results on authenticity, with some experts noting stylistic similarities to Smith's but lacking definitive provenance, underscoring the reliance on faith-based validation among recruits.[31][17]Theological Framework and Innovations

Core Revelations and Scriptural Additions

Strang's initial scriptural addition came through the Voree plates, three brass plates unearthed on September 13, 1845, in a hillside near Voree, Wisconsin, beneath the roots of an oak tree, as directed by an angelic vision reported by Strang.[24] The plates, measuring approximately 7 by 9 inches, bore engravings including alphabetic characters and symbolic imagery such as a landscape and a crowned figure with a scepter; Strang translated them using the Urim and Thummim, yielding a brief prophetic record titled "The Record of Rajah Manchou of Vorito," which lamented the destruction of an ancient people and affirmed Strang's divine appointment as prophet, seer, and revelator.[24] Four witnesses—Aaron Smith, Jirah B. Wheelan, James M. Van Nostrand, and Edward Whitcomb—testified to excavating the plates, and Strang publicly displayed them to additional observers, including three more who later signed a supporting affidavit, paralleling the witness model for the Book of Mormon plates.[24] [10] Subsequent revelations, received between 1844 and 1849 and compiled as authoritative scripture akin to the Doctrine and Covenants, addressed foundational doctrines including prophetic succession, tithing, and gathering. A revelation dated January 17, 1845, mandated tithing as one-tenth of one's time and labor rather than mere income, emphasizing stewardship and self-sufficiency for the gathered saints at Voree, designated as a new stake of Zion.[33] Another, from September 1, 1845, explicitly commanded translation of the Voree plates and warned of judgment on dissenters, reinforcing Strang's authority through ancient validation.[33] Further revelations outlined priesthood ordinances, such as building a house of the Lord in Voree by July 1, 1846, for endowments and baptisms for the dead (detailed August 9, 1849), and the Order of Enoch on January 7, 1849, promoting communal unity, strict consecration, and inheritance laws favoring primogeniture to preserve covenant lines.[33] The most substantial scriptural expansion was the Book of the Law of the Lord, published in 1851 as a translation from ancient brass plates—allegedly the Plates of Laban from the Book of Mormon—revealed to Strang by an angel on April 5, 1850, near White Rock Springs, Wisconsin.[34] Spanning over 250 pages across 41 chapters, it purportedly chronicled laws from Adam through Moses, integrating biblical-style commandments on governance, with additions like prohibitions on usury, detailed inheritance protocols prioritizing eldest sons, and prophetic tests requiring dual witnesses for divine claims.[34] The text incorporated Strang's own revelations, such as those from July 8, 1850, on ecclesiastical courts and restitution, prefaced by testimonies from 11 witnesses who viewed the plates, positioning it as a restored Mosaic code binding Strangite practice and authority.[34] These additions collectively emphasized a return to patriarchal, theocratic order, distinct from contemporaneous Latter Day Saint developments.[33]Distinctive Doctrines on Prophecy and Authority

Strang asserted that legitimate prophetic succession required a direct, written appointment from the predecessor prophet, interpreting Doctrine and Covenants sections 43:2–4 as mandating such confirmation by "the voice of him who hath appointed him" to avoid unauthorized claims. He presented a letter purportedly signed by Joseph Smith on June 18, 1844—two days before Smith's death—designating Strang as successor and instructing him to establish a stake in Voree, Wisconsin, which Strang argued fulfilled biblical patterns of prophetic installation seen in Moses' appointment of Joshua.[35][36] This contrasted with quorum-based models, emphasizing individual divine designation over collective priesthood keys held by the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[2] Central to Strang's validation of prophetic authority was the requirement for seers to produce and translate ancient, buried records as empirical proof of their calling, a criterion he derived from scriptural precedents like Joseph's translation of the golden plates and Moses' reception of engraved tables. In 1845, following a revelatory vision, Strang unearthed the three Voree Plates—brass artifacts buried near White River, Wisconsin—along with instructions to translate them using the Urim and Thummim, yielding a short record prophesying Smith's martyrdom and Strang's rise as the "mighty prophet" to translate further sealed records.[26][28] This act, he contended, distinguished true prophets from false claimants, as ongoing revelation demanded tangible scriptural additions rather than mere administrative continuity.[33] Strang's framework vested comprehensive authority in the living prophet as seer, revelator, and translator, who alone held the keys to bind or loose on earth and in heaven, with revelations serving as binding law when canonized. He claimed angelic ordinations—by John the Baptist and others—affirmed his mantle but subordinated them to Joseph's appointment, enabling him to issue revelations from 1844 to 1856 that guided church polity, including theocratic governance and ritual practices.[12][33] Under this doctrine, the prophet's voice equated to God's, subjecting all teachings to his measurement, though Strang warned against blind obedience without miraculous corroboration, positioning his authority as causally rooted in verifiable divine signs rather than institutional consensus.[35]Liturgical and Communal Practices

The Strangite church observed the seventh day of the week, Saturday, as the Sabbath for worship services, pursuant to a revelation received by James Strang declaring Sunday observance a corruption instituted by the Catholic Church to alter the biblical mandate.[37] Services on this day focused on rest, scriptural study, prayer, and fostering communal unity, while permitting practical labors such as animal care deemed necessary for sustenance.[37] This practice distinguished Strangites from contemporaneous Latter Day Saint groups adhering to first-day worship and reflected Strang's emphasis on restoring Mosaic law elements within a Christian framework.[38] Ordinances included baptism by immersion for both the living and the dead, the latter conducted under special dispensation owing to the absence of a dedicated temple and limited initially at Voree, Wisconsin, and later on Beaver Island, Michigan.[39] Sacrificial rites, detailed in Strang's Book of the Law of the Lord (published 1851), mandated offerings of first fruits and animal victims, with male priests exclusively authorized to perform the slaying as part of Aaronic priesthood duties.[40][38] Women were ordained to select Aaronic offices, such as teacher or priest, but prohibited from sacrificial killings, underscoring gendered restrictions within the priesthood hierarchy.[41] Priesthood vestments featured prescribed robes of fine linen in specific colors and styles—gold for the Melchizedek priesthood symbolizing endless life, silver for lesser orders—with additional ornaments like ephods for high priests during rituals.[42] A prominent liturgical innovation was the monarchical coronation of Strang as king on July 8, 1850, in Beaver Island's open-air log tabernacle, where his twelve apostles anointed him amid an assembly of about 300 adherents; Strang donned a scarlet robe, paper crown, and scepter in a ceremony evoking biblical precedents for divine kingship.[2] Unlike endowments in other Latter Day Saint traditions, Strangites eschewed secret temple rituals, reserving authoritative ordinances solely to prophets like Strang.[43] Communal practices integrated liturgical elements into daily theocratic governance on Beaver Island, where Strang's monarchy enforced tithing of produce and labor, communal resource allocation for industries like fishing and printing, and adherence to the Book of the Law's statutes on morality and Sabbath observance to sustain group cohesion and self-reliance.[40] This structure prioritized prophetic direction over democratic processes, with apostles and a royal guard aiding enforcement, though internal schisms later arose over polygamy's introduction in 1852.[2]Publications and Written Works

Major Texts and Their Content

Strang's primary doctrinal texts consisted of claimed divine revelations and translations from purported ancient metal plates, which he presented as scriptural additions to Mormonism. These works emphasized prophetic authority, succession from Joseph Smith, restoration of Mosaic law, and establishment of a theocratic order. Collections of his revelations, compiled posthumously in volumes such as The Revelations of James J. Strang (editions including 1939 and 1990), documented communications purportedly received from God between September 1844 and 1849.[44][45] These addressed church governance, condemnation of rival succession claimants like Brigham Young, directives for gathering saints to Voree, Wisconsin, and validations of Strang's prophetic mantle through angelic ordination and plate discoveries.[26] The Voree Plates, unearthed on September 1, 1845, under an oak tree in Whitewater, Wisconsin (later named Voree), comprised three small brass plates measuring about 3 by 4 inches each, with engraved alphabetic characters on one side and symbolic illustrations on the other.[24] Strang asserted their translation, achieved via the Urim and Thummim within five days, yielded The Voree Record, a brief prophetic narrative from ancient American inhabitants (Rajah Manchou of Vorito) foretelling Joseph Smith's role as a "forerunner" prophet, his martyrdom by conspirators, apostasy in the church, and the rise of a "mighty prophet" successor at Voree tasked with translating lost records and enacting God's law.[24][20] Most substantively, The Book of the Law of the Lord (first edition 1851; revised 1856) derived from larger brass plates Strang claimed were delivered by an angel in 1849 near the site of the Voree Plates, purporting to contain an Egyptian transcription of Mosaic law inscribed at Sinai and preserved through Israelite history.[34] The text, spanning over 200 pages with notes and references, adapted Pentateuchal commandments into a comprehensive theocratic code, mandating the prophet's dual role as ecclesiastical head and hereditary king, detailed inheritance laws favoring male primogeniture, tithing as one-tenth of increase, priestly ordinances including washings and anointings, and communal practices like insular dress codes and Sabbath observance.[34] It incorporated brief additional revelations on topics such as prophetic translation gifts and church courts, positioning the work as a constitutional blueprint for a restored Israelite kingdom under Strang's leadership.[46]Role in Proselytizing and Doctrinal Dissemination