Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

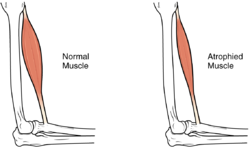

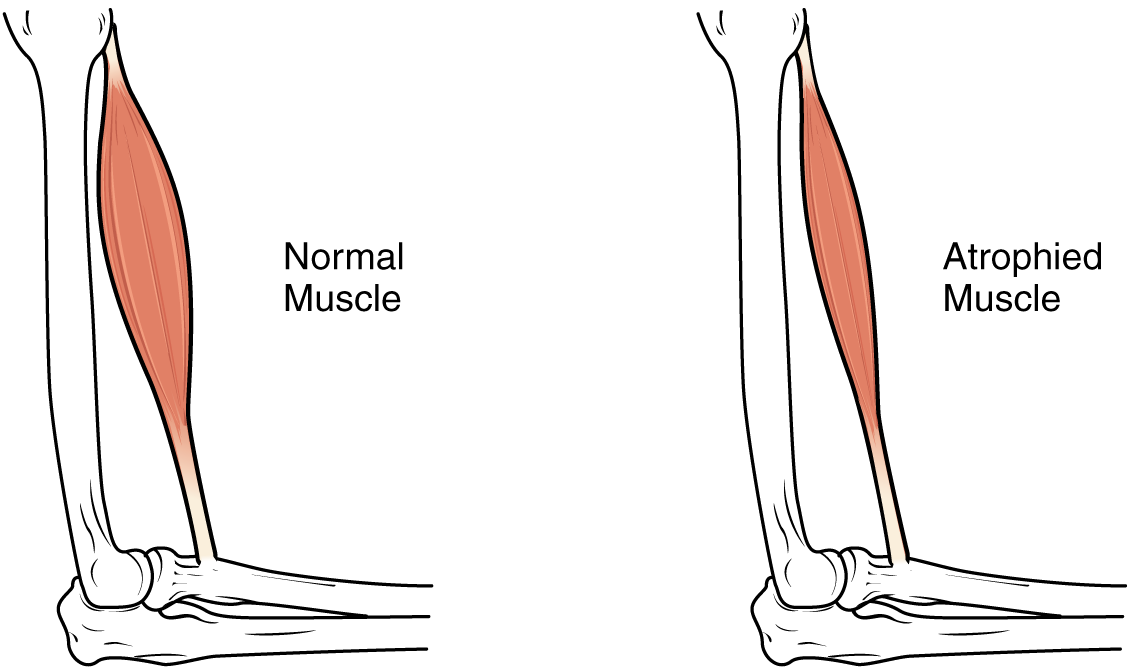

Muscle atrophy

View on Wikipedia| Muscle atrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| The size of the muscle is reduced, as a consequence there is a loss of strength and mobility. | |

| Specialty | Physical medicine and rehabilitation |

Muscle atrophy is the loss of skeletal muscle mass. It can be caused by immobility, aging, malnutrition, medications, or a wide range of injuries or diseases that impact the musculoskeletal or nervous system. Muscle atrophy leads to muscle weakness and causes disability.

Disuse causes rapid muscle atrophy and often occurs during injury or illness that requires immobilization of a limb or bed rest. Depending on the duration of disuse and the health of the individual, this may be fully reversed with activity. Malnutrition first causes fat loss but may progress to muscle atrophy in prolonged starvation and can be reversed with nutritional therapy. In contrast, cachexia is a wasting syndrome caused by an underlying disease such as cancer that causes dramatic muscle atrophy and cannot be completely reversed with nutritional therapy. Sarcopenia is age-related muscle atrophy and can be slowed by exercise. Finally, diseases of the muscles such as muscular dystrophy or myopathies can cause atrophy, as well as damage to the nervous system such as in spinal cord injury or stroke. Thus, muscle atrophy is usually a finding (sign or symptom) in a disease rather than being a disease by itself. However, some syndromes of muscular atrophy are classified as disease spectrums or disease entities rather than as clinical syndromes alone, such as the various spinal muscular atrophies.

Muscle atrophy results from an imbalance between protein synthesis and protein degradation, although the mechanisms are incompletely understood and are variable depending on the cause. Muscle loss can be quantified with advanced imaging studies but this is not frequently pursued. Treatment depends on the underlying cause but will often include exercise and adequate nutrition. Anabolic agents may have some efficacy but are not often used due to side effects. There are multiple treatments and supplements under investigation but there are currently limited treatment options in clinical practice. Given the implications of muscle atrophy and limited treatment options, minimizing immobility is critical in injury or illness.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The hallmark sign of muscle atrophy is loss of lean muscle mass. This change may be difficult to detect due to obesity, changes in fat mass or edema. Changes in weight, limb or waist circumference are not reliable indicators of muscle mass changes.[1]

The predominant symptom is increased weakness which may result in difficulty or inability in performing physical tasks depending on what muscles are affected. Atrophy of the core or leg muscles may cause difficulty standing from a seated position, walking or climbing stairs and can cause increased falls. Atrophy of the throat muscles may cause difficulty swallowing and diaphragm atrophy can cause difficulty breathing. Muscle atrophy can be asymptomatic and may go undetected until a significant amount of muscle is lost.[2]

Causes

[edit]

Skeletal muscle serves as a storage site for amino acids, creatine, myoglobin, and adenosine triphosphate, which can be used for energy production when demands are high or supplies are low. If metabolic demands remain greater than protein synthesis, muscle mass is lost.[3] Many diseases and conditions can lead to this imbalance, either through the disease itself or disease associated appetite-changes, such as loss of taste due to Covid-19. Causes of muscle atrophy, include immobility, aging, malnutrition, certain systemic diseases (cancer, congestive heart failure; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AIDS, liver disease, etc.), deinnervation, intrinsic muscle disease or medications (such as glucocorticoids).[4]

Immobility

[edit]Disuse is a common cause of muscle atrophy and can be local (due to injury or casting) or general (bed-rest). The rate of muscle atrophy from disuse (10–42 days) is approximately 0.5–0.6% of total muscle mass per day although there is considerable variation between people.[5] The elderly are the most vulnerable to dramatic muscle loss with immobility. Much of the established research has investigated prolonged disuse (>10 days), in which the muscle is compromised primarily by declines in muscle protein synthesis rates rather than changes in muscle protein breakdown. There is evidence to suggest that there may be more active protein breakdown during short term immobility (<10 days).[5]

Cachexia

[edit]Certain diseases can cause a complex muscle wasting syndrome known as cachexia. It is commonly seen in cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease and AIDS although it is associated with many disease processes, usually with a significant inflammatory component. Cachexia causes ongoing muscle loss that is not entirely reversed with nutritional therapy.[6] The pathophysiology is incompletely understood but inflammatory cytokines are considered to play a central role. In contrast to weight loss from inadequate caloric intake, cachexia causes predominantly muscle loss instead of fat loss and it is not as responsive to nutritional intervention. Cachexia can significantly compromise quality of life and functional status and is associated with poor outcomes.[7][8]

Sarcopenia

[edit]Sarcopenia is the degenerative loss of skeletal muscle mass, quality, and strength associated with aging. This involves muscle atrophy, reduction in number of muscle fibers and a shift towards "slow twitch" or type I skeletal muscle fibers over "fast twitch" or type II fibers.[3] The rate of muscle loss is dependent on exercise level, co-morbidities, nutrition and other factors. There are many proposed mechanisms of sarcopenia, such as a decreased capacity for oxidative phosphorylation, cellular senescence or an altered signaling of pathways regulating protein synthesis,[9] and is considered to be the result of changes in muscle synthesis signalling pathways and gradual failure in the satellite cells which help to regenerate skeletal muscle fibers, specifically in "fast twitch" myofibers.[10]

Sarcopenia can lead to reduction in functional status and cause significant disability but is a distinct condition from cachexia although they may co-exist.[8][11] In 2016 an ICD code for sarcopenia was released, contributing to its acceptance as a disease entity.[12]

Intrinsic muscle diseases

[edit]

Muscle diseases, such as muscular dystrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or myositis such as inclusion body myositis can cause muscle atrophy.[13]

Central nervous system damage

[edit]Damage to neurons in the brain or spinal cord can cause prominent muscle atrophy. This can be localized muscle atrophy and weakness or paralysis such as in stroke or spinal cord injury.[14] More widespread damage such as in traumatic brain injury or cerebral palsy can cause generalized muscle atrophy.[15]

Peripheral nervous system damage

[edit]Injuries or diseases of peripheral nerves supplying specific muscles can also cause muscle atrophy. This is seen in nerve injury due to trauma or surgical complication, nerve entrapment, or inherited diseases such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.[16]

Medications

[edit]Some medications are known to cause muscle atrophy, usually due to direct effect on muscles. This includes glucocorticoids causing glucocorticoid myopathy[4] or medications toxic to muscle such as doxorubicin.[17]

Endocrinopathies

[edit]Disorders of the endocrine system such as Cushing's disease or hypothyroidism are known to cause muscle atrophy.[18]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Muscle atrophy occurs due to an imbalance between the normal balance between protein synthesis and protein degradation. This involves complex cell signalling that is incompletely understood and muscle atrophy is likely the result of multiple contributing mechanisms.[19]

Mitochondrial function is crucial to skeletal muscle health and detrimental changes at the level of the mitochondria may contribute to muscle atrophy.[20] A decline in mitochondrial density as well as quality is consistently seen in muscle atrophy due to disuse.[20]

The ATP-dependent ubiquitin/proteasome pathway is one mechanism by which proteins are degraded in muscle. This involves specific proteins being tagged for destruction by a small peptide called ubiquitin which allows recognition by the proteasome to degrade the protein.[21]

Diagnosis

[edit]Screening for muscle atrophy is limited by a lack of established diagnostic criteria, although many have been proposed. Diagnostic criteria for other conditions such as sarcopenia or cachexia can be used.[3] These syndromes can also be identified with screening questionnaires.[citation needed]

Muscle mass and changes can be quantified on imaging studies such as CT scans or Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Biomarkers such as urine urea can be used to roughly estimate muscle loss during circumstances of rapid muscle loss.[22] Other biomarkers are currently under investigation but are not used in clinical practice.[3]

Treatment

[edit]Muscle atrophy can be delayed, prevented and sometimes reversed with treatment. Treatment approaches include impacting the signaling pathways that induce muscle hypertrophy or slow muscle breakdown as well as optimizing nutritional status.[citation needed]

Physical activity provides a significant anabolic muscle stimulus and is a crucial component to slowing or reversing muscle atrophy.[3] It is still unknown regarding the ideal exercise "dosing." Resistance exercise has been shown to be beneficial in reducing muscle atrophy in older adults.[23][24] In patients who cannot exercise due to physical limitations such as paraplegia, functional electrical stimulation can be used to externally stimulate the muscles.[25]

Adequate calories and protein is crucial to prevent muscle atrophy. Protein needs may vary dramatically depending on metabolic factors and disease state, so high-protein supplementation may be beneficial.[3] Supplementation of protein or branched-chain amino acids, especially leucine, can provide a stimulus for muscle synthesis and inhibit protein breakdown and has been studied for muscle atrophy for sarcopenia and cachexia.[3][26] β-Hydroxy β-methylbutyrate (HMB), a metabolite of leucine which is sold as a dietary supplement, has demonstrated efficacy in preventing the loss of muscle mass in several muscle wasting conditions in humans, particularly sarcopenia.[26][27][28] Based upon a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials that was published in 2015, HMB supplementation has efficacy as a treatment for preserving lean muscle mass in older adults.[29] More research is needed to determine the precise effects of HMB on muscle strength and function in various populations.[29]

In severe cases of muscular atrophy, the use of an anabolic steroid such as methandrostenolone may be administered to patients as a potential treatment although use is limited by side effects. A novel class of drugs, called selective androgen receptor modulators, is being investigated with promising results. They would have fewer side effects, while still promoting muscle and bone tissue growth and regeneration. These effects have yet to be confirmed in larger clinical trials.[30]

Outcomes

[edit]Outcomes of muscle atrophy depend on the underlying cause and the health of the patient. Immobility or bed rest in populations predisposed to muscle atrophy, such as the elderly or those with disease states that commonly cause cachexia, can cause dramatic muscle atrophy and impact on functional outcomes. In the elderly, this often leads to decreased biological reserve and increased vulnerability to stressors known as the "frailty syndrome."[3] Loss of lean body mass is also associated with increased risk of infection, decreased immunity, and poor wound healing. The weakness that accompanies muscle atrophy leads to higher risk of falls, fractures, physical disability, need for institutional care, reduced quality of life, increased mortality, and increased healthcare costs.[3]

Other animals

[edit]Inactivity and starvation in mammals lead to atrophy of skeletal muscle, accompanied by a smaller number and size of the muscle cells as well as lower protein content.[31] In humans, prolonged periods of immobilization, as in the cases of bed rest or astronauts flying in space, are known to result in muscle weakening and atrophy. Such consequences are also noted in small hibernating mammals like the golden-mantled ground squirrels and brown bats.[32] A striking example of human-induced atrophy is seen in Amar Bharati, an Indian sadhu who held his arm raised for decades as a spiritual devotion, resulting in severe muscle atrophy and loss of function in the limb.

Bears are an exception to this rule; species in the family Ursidae are famous for their ability to survive unfavorable environmental conditions of low temperatures and limited nutrition availability during winter by means of hibernation. During that time, bears go through a series of physiological, morphological, and behavioral changes.[33] Their ability to maintain skeletal muscle number and size during disuse is of significant importance.[citation needed]

During hibernation, bears spend 4–7 months of inactivity and anorexia without undergoing muscle atrophy and protein loss.[32] A few known factors contribute to the sustaining of muscle tissue. During the summer, bears take advantage of the nutrition availability and accumulate muscle protein. The protein balance at time of dormancy is also maintained by lower levels of protein breakdown during the winter.[32] At times of immobility, muscle wasting in bears is also suppressed by a proteolytic inhibitor that is released in circulation.[31] Another factor that contributes to the sustaining of muscle strength in hibernating bears is the occurrence of periodic voluntary contractions and involuntary contractions from shivering during torpor.[34] The three to four daily episodes of muscle activity are responsible for the maintenance of muscle strength and responsiveness in bears during hibernation.[34]

Pre-clinical models

[edit]Muscle-atrophy can be induced in pre-clinical models (e.g. mice) to study the effects of therapeutic interventions against muscle-atrophy. Restriction of the diet, i.e. caloric restriction, leads to a significant loss of muscle mass within two weeks, and loss of muscle-mass can be rescued by a nutritional intervention.[35] Immobilization of one of the hindlegs of mice leads to muscle-atrophy as well, and is hallmarked by loss of both muscle mass and strength. Food restriction and immobilization may be used in mouse models and have been shown to overlap with mechanisms associated to sarcopenia in humans.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dev R (January 2019). "Measuring cachexia-diagnostic criteria". Annals of Palliative Medicine. 8 (1): 24–32. doi:10.21037/apm.2018.08.07. PMID 30525765.

- ^ Cretoiu SM, Zugravu CA (2018). "Nutritional Considerations in Preventing Muscle Atrophy". In Xiao J (ed.). Muscle Atrophy. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1088. Springer Singapore. pp. 497–528. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-1435-3_23. ISBN 978-981-13-1434-6. PMID 30390267.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Argilés JM, Campos N, Lopez-Pedrosa JM, Rueda R, Rodriguez-Mañas L (September 2016). "Skeletal Muscle Regulates Metabolism via Interorgan Crosstalk: Roles in Health and Disease". Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 17 (9): 789–96. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.04.019. hdl:11268/9072. PMID 27324808.

- ^ a b Seene T (July 1994). "Turnover of skeletal muscle contractile proteins in glucocorticoid myopathy". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 50 (1–2): 1–4. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(94)90165-1. PMID 8049126. S2CID 27814895.

- ^ a b Wall BT, Dirks ML, van Loon LJ (September 2013). "Skeletal muscle atrophy during short-term disuse: implications for age-related sarcopenia". Ageing Research Reviews. 12 (4): 898–906. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2013.07.003. PMID 23948422. S2CID 30149063.

- ^ Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argilés J, Bales C, Baracos V, Guttridge D, et al. (December 2008). "Cachexia: a new definition". Clinical Nutrition. 27 (6): 793–9. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2008.06.013. PMID 18718696. S2CID 206821612.

- ^ Morley JE, Thomas DR, Wilson MM (April 2006). "Cachexia: pathophysiology and clinical relevance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 83 (4): 735–43. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.4.735. PMID 16600922.

- ^ a b Peterson SJ, Mozer M (February 2017). "Differentiating Sarcopenia and Cachexia Among Patients With Cancer". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 32 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1177/0884533616680354. PMID 28124947. S2CID 206555460.

- ^ de Jong J (February 2023). "Sex differences in skeletal muscle-aging trajectory: same processes, but with a different ranking". GeroScience (Original Research). 45 (4): 2367–2386. doi:10.1007/s11357-023-00750-4. PMC 10651666. PMID 36820956.

- ^ Verdijk L (January 2007). "Satellite cell content is specifically reduced in type II skeletal muscle fibers in the elderly". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism (Original Research). 292 (1): E151 – E157. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00278.2006. PMID 16926381.

- ^ Marcell TJ (October 2003). "Sarcopenia: causes, consequences, and preventions". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 58 (10): M911-6. doi:10.1093/gerona/58.10.m911. PMID 14570858.

- ^ Anker SD, Morley JE, von Haehling S (December 2016). "Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia". Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 7 (5): 512–514. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12147. PMC 5114626. PMID 27891296.

- ^ Powers SK, Lynch GS, Murphy KT, Reid MB, Zijdewind I (November 2016). "Disease-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and Fatigue". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 48 (11): 2307–2319. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000975. PMC 5069191. PMID 27128663.

- ^ O'Brien LC, Gorgey AS (October 2016). "Skeletal muscle mitochondrial health and spinal cord injury". World Journal of Orthopedics. 7 (10): 628–637. doi:10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.628. PMC 5065669. PMID 27795944.

- ^ Verschuren O, Smorenburg AR, Luiking Y, Bell K, Barber L, Peterson MD (June 2018). "Determinants of muscle preservation in individuals with cerebral palsy across the lifespan: a narrative review of the literature". Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 9 (3): 453–464. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12287. PMC 5989853. PMID 29392922.

- ^ Wong A, Pomerantz JH (March 2019). "The Role of Muscle Stem Cells in Regeneration and Recovery after Denervation: A Review". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 143 (3): 779–788. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005370. PMID 30817650. S2CID 73495244.

- ^ Hiensch AE, Bolam KA, Mijwel S, Jeneson JA, Huitema AD, Kranenburg O, et al. (October 2019). "Doxorubicin-induced skeletal muscle atrophy: elucidating the underlying molecular pathways". Acta Physiologica. 229 (2) e13400. doi:10.1111/apha.13400. PMC 7317437. PMID 31600860.

- ^ Martín AI, Priego T, López-Calderón A (2018). "Hormones and Muscle Atrophy". In Xiao J (ed.). Muscle Atrophy. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1088. Springer Singapore. pp. 207–233. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-1435-3_9. ISBN 978-981-13-1434-6. PMID 30390253.

- ^ Egerman MA, Glass DJ (Jan–Feb 2014). "Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass". Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 49 (1): 59–68. doi:10.3109/10409238.2013.857291. PMC 3913083. PMID 24237131.

- ^ a b Abrigo J, Simon F, Cabrera D, Vilos C, Cabello-Verrugio C (2019-05-20). "Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Skeletal Muscle Pathologies". Current Protein & Peptide Science. 20 (6): 536–546. doi:10.2174/1389203720666190402100902. PMID 30947668. S2CID 96434115.

- ^ Sandri M (June 2008). "Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy". Physiology. 23 (3). Bethesda, Md.: 160–70. doi:10.1152/physiol.00041.2007. PMID 18556469.

- ^ Bishop J, Briony T (2007). "Section 1.9.2". Manual of Dietetic Practice. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4051-3525-2.

- ^ Sayer AA (November 2014). "Sarcopenia the new geriatric giant: time to translate research findings into clinical practice". Age and Ageing. 43 (6): 736–7. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu118. PMID 25227204.

- ^ Liu CJ, Latham NK (July 2009). "Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (3) CD002759. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002759.pub2. PMC 4324332. PMID 19588334.

- ^ Zhang D, Guan TH, Widjaja F, Ang WT (23 April 2007). Functional electrical stimulation in rehabilitation engineering: A survey. Proceedings of the 1st international convention on Rehabilitation engineering & assistive technology: in conjunction with 1st Tan Tock Seng Hospital Neurorehabilitation Meeting. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 221–226. doi:10.1145/1328491.1328546. ISBN 978-1-59593-852-7.

- ^ a b Phillips SM (July 2015). "Nutritional supplements in support of resistance exercise to counter age-related sarcopenia". Advances in Nutrition. 6 (4): 452–60. doi:10.3945/an.115.008367. PMC 4496741. PMID 26178029.

- ^ Brioche T, Pagano AF, Py G, Chopard A (August 2016). "Muscle wasting and aging: Experimental models, fatty infiltrations, and prevention" (PDF). Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 50: 56–87. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2016.04.006. PMID 27106402. S2CID 29717535.

- ^ Holeček M (August 2017). "Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation and skeletal muscle in healthy and muscle-wasting conditions". Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 8 (4): 529–541. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12208. PMC 5566641. PMID 28493406.

- ^ a b Wu H, Xia Y, Jiang J, Du H, Guo X, Liu X, et al. (2015). "Effect of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation on muscle loss in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 61 (2): 168–75. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.020. PMID 26169182.

- ^ Srinath R, Dobs A (February 2014). "Enobosarm (GTx-024, S-22): a potential treatment for cachexia". Future Oncology. 10 (2): 187–94. doi:10.2217/fon.13.273. PMID 24490605.

- ^ a b Fuster G, Busquets S, Almendro V, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM (October 2007). "Antiproteolytic effects of plasma from hibernating bears: a new approach for muscle wasting therapy?". Clinical Nutrition. 26 (5): 658–61. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2007.07.003. PMID 17904252.

- ^ a b c Lohuis TD, Harlow HJ, Beck TD (May 2007). "Hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus) experience skeletal muscle protein balance during winter anorexia". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 147 (1): 20–8. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.12.020. PMID 17307375.

- ^ Carey HV, Andrews MT, Martin SL (October 2003). "Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature". Physiological Reviews. 83 (4): 1153–81. doi:10.1152/physrev.00008.2003. PMID 14506303.

- ^ a b Harlow HJ, Lohuis T, Anderson-Sprecher RC, Beck TD (2004). "Body Surface Temperature Of Hibernating Black Bears May Be Related To Periodic Muscle Activity". Journal of Mammalogy. 85 (3): 414–419. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2004)085<0414:BSTOHB>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86315375.

- ^ van den Hoek A (August 2019). "A novel nutritional supplement prevents muscle loss and accelerates muscle mass recovery in caloric-restricted mice". Metabolism (Original Research). 97: 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.05.012. PMID 31153978.

- ^ de Jong J (June 2023). "Caloric Restriction Combined with Immobilization as Translational Model for Sarcopenia Expressing Key-Pathways of Human Pathology". Aging and Disease (Original Research). 14 (3): 937–957. doi:10.14336/AD.2022.1201. PMC 10187708. PMID 37191430.

External links

[edit] Media related to Muscle atrophy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Muscle atrophy at Wikimedia Commons- Muscular atrophy at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)