Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cathepsin

View on Wikipedia| Cathepsin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

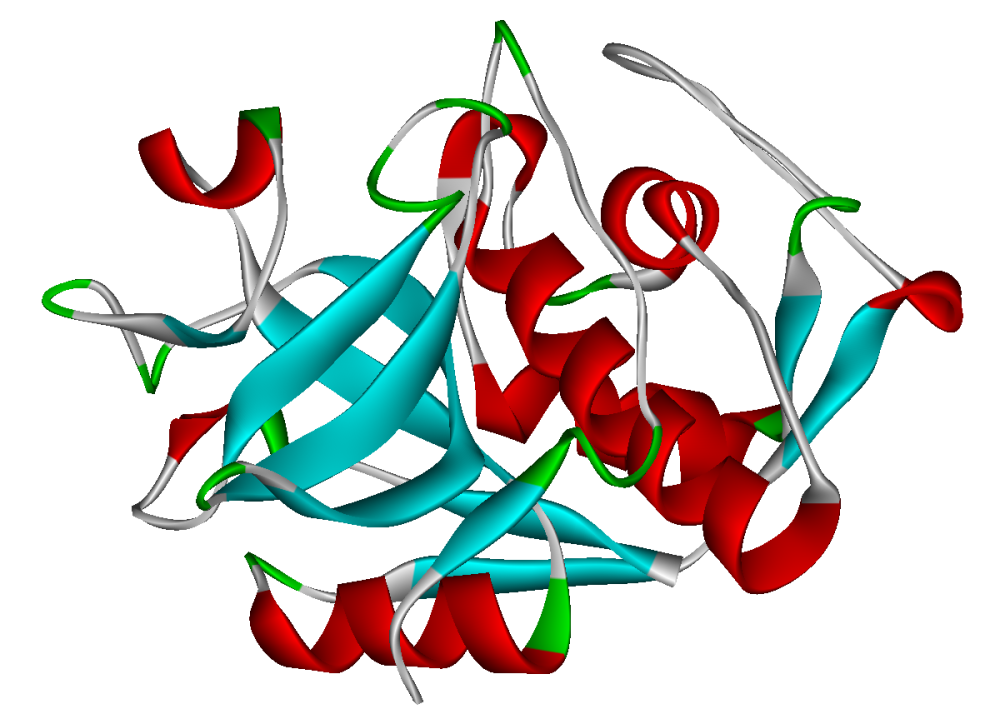

Structure of Cathepsin K | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CTP | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00112 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0125 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000668 | ||||||||

| SMART | Pept_C1 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00126 | ||||||||

| MEROPS | C1 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1aec / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Cathepsins (Ancient Greek kata- "down" and hepsein "boil"; abbreviated CTS) are proteases (enzymes that degrade proteins) found in all animals as well as other organisms. There are approximately a dozen members of this family, which are distinguished by their structure, catalytic mechanism, and which proteins they cleave[citation needed]. Most of the members become activated at the low pH found in lysosomes. Thus, the activity of this family lies almost entirely within those organelles. There are, however, exceptions such as cathepsin K, which works extracellularly after secretion by osteoclasts in bone resorption. Cathepsins have a vital role in mammalian cellular turnover.

Classification

[edit]- Cathepsin A (serine protease)

- Cathepsin B (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin C (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin D (aspartyl protease)

- Cathepsin E (aspartyl protease)

- Cathepsin F (cysteine proteinase)

- Cathepsin G (serine protease)

- Cathepsin H (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin K (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin L1 (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin L2 (or V) (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin O (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin P (mouse cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin Q (rat cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin S (cysteine protease)

- Cathepsin W (cysteine proteinase)

- Cathepsin Z (or X) (cysteine protease)

Clinical significance

[edit]Cathepsins are involved in many physiological processes and have been implicated in a number of human diseases. The cysteine cathepsins have attracted significant research effort as drug targets.[1][2]

- Cancer, Cathepsin D is a mitogen and "it attenuates the anti-tumor immune response of decaying chemokines to inhibit the function of dendritic cells". Cathepsins B and L are involved in matrix degradation and cell invasion.[3]

- Stroke[4]

- Traumatic brain injury[5]

- Alzheimer's disease[6]

- Arthritis[7]

- Ebola, Cathepsin B and to a lesser extent cathepsin L have been found to be necessary for the virus to enter host cells.[8]

- COPD

- Chronic periodontitis

- Pancreatitis

- Several ocular disorders: keratoconus, retinal detachment, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma.[9]

Cathepsin A

[edit]Deficiencies in this protein are linked to multiple forms of galactosialidosis. The cathepsin A activity in lysates of metastatic lesions of malignant melanoma is significantly higher than in primary focus lysates. Cathepsin A increased in muscles moderately affected by muscular dystrophy and denervating diseases.

Cathepsin B

[edit]Cathepsin B may function as a beta-secretase 1, cleaving amyloid precursor protein to produce amyloid beta.[10] Overexpression of the encoded protein, which is a member of the peptidase C1 family, has been associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma and other tumors.[11] Cathepsin B has also been implicated in the progression of various human tumors[3] including ovarian cancer.

Cathepsin D

[edit]Cathepsin D (an aspartyl protease) appears to cleave a variety of substrates such as fibronectin and laminin. Unlike some of the other cathepsins, cathepsin D has some protease activity at neutral pH.[12] High levels of this enzyme in tumor cells seems to be associated with greater invasiveness.

Cathepsin K

[edit]Cathepsin K is the most potent mammalian collagenase. Cathepsin K is involved in osteoporosis, a disease in which a decrease in bone density causes an increased risk for fracture. Osteoclasts are the bone resorbing cells of the body, and they secrete cathepsin K in order to break down collagen, the major component of the non-mineral protein matrix of the bone.[13] Cathepsin K, among other cathepsins, plays a role in cancer metastasis through the degradation of the extracellular matrix.[14] The genetic knockout for cathepsin S and K in mice with atherosclerosis was shown to reduce the size of atherosclerotic lesions.[15] The expression of cathepsin K in cultured endothelial cells is regulated by shear stress.[16] Cathepsin K has also been shown to play a role in arthritis.[17]

Cathepsin V

[edit]Mouse cathepsin L is homologous to human cathepsin V.[18] Mouse cathepsin L has been shown to play a role in adipogenesis and glucose intolerance in mice. Cathepsin L degrades fibronectin, insulin receptor (IR), and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R). Cathepsin L-deficient mice were shown to have less adipose tissue, lower serum glucose and insulin levels, more insulin receptor subunits, more glucose transporter (GLUT4) and more fibronectin than wild type controls.[19]

Inhibitors

[edit]Five cyclic peptides show inhibitory activity towards human cathepsins L, B, H, and K.[20] Several inhibitors have reached clinical trials, targeting cathepsins K and S as promising therapeutics for osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and chronic pain. Cathepsin K inhibitors, Relacatib, Balicatib, and Odanacatib, were terminated during clinical trials at phases I, II, and III, respectively, owing to adverse side effects.[21] SAR114137, a Cathepsin S inhibitor, did not progress past phase I for chronic pain. In 2022, STI-1558, a Cathepsin L inhibitor, received FDA clearance to begin phase I studies to treat COVID-19.[22]

Cathepsin zymography

[edit]Zymography is a type of gel electrophoresis that uses a polyacrylamide gel co-polymerized with a substrate in order to detect enzyme activity. Cathepsin zymography separates different cathepsins based on their migration through a polyacrylamide gel co-polymerized with a gelatin substrate. The electrophoresis takes place in non-reducing conditions, and the enzymes are protected from denaturation using leupeptin.[23] After protein concentration is determined, equal amounts of tissue protein are loaded into a gel. The protein is then allowed to migrate through the gel. After electrophoresis, the gel is put into a renaturing buffer in order to return the cathepsins to their native conformation. The gel is then put into an activation buffer of a specific pH and left to incubate overnight at 37 °C. This activation step allows the cathepsins to degrade the gelatin substrate. When the gel is stained using a Coomassie blue stain, areas of the gel still containing gelatin appear blue. The areas of the gel where cathepsins were active appear as white bands. This cathepsin zymography protocol has been used to detect femtomole quantities of mature cathepsin K.[23] The different cathepsins can be identified based on their migration distance due to their molecular weights: cathepsin K (~37 kDa), V (~35 kDa), S (~25kDa), and L (~20 kDa). Cathepsins have specific pH levels at which they have optimum proteolytic activity. Cathepsin K is able to degrade gelatin at pH 7 and 8, but these pH levels do not allow for cathepsins L and V activity. At a pH 4 cathepsin V is active, but cathepsin K is not. Adjusting the pH of the activation buffer can allow for further identification of cathepsin types.[24]

History

[edit]The term cathepsin was coined in 1929 by Richard Willstätter and Eugen Bamann to describe a proteolytic activity of leukocytes and tissues at slightly acidic pH (Willstätter & Bamann (1929) Hoppe-Seylers Z. Physiol. Chemie 180, 127-143). The earliest record of "cathepsin" found in the MEDLINE database (e.g., via PubMed) is from the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1949.[25] However, references within this article indicate that cathepsins were first identified and named around the turn of the 20th century. Much of this earlier work was done in the laboratory of Max Bergmann, who spent the first several decades of the century defining these proteases.[26]

It is notable that research published in the 1930s (primarily by Bergmann) used the term "catheptic enzymes" to refer to a broad family of proteases that included papain, bromelin, and cathepsin itself.[27] Initial efforts to purify and characterize proteases using hemoglobin transpired at a time when the word "cathepsin" indicated a single enzyme;[28] the existence of multiple, distinct cathepsin family members (e.g. B, H, L) did not appear to be understood at the time. However, by 1937 Bergmann and colleagues began to differentiate cathepsins on the basis of their source in the human body (e.g. liver cathepsin, spleen cathepsin).[26]

References

[edit]- ^ Novinec, Marko; Lenarčič, Brigita (1 June 2013). "Papain-like peptidases: structure, function, and evolution". BioMolecular Concepts. 4 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1515/bmc-2012-0054. PMID 25436581. S2CID 2112616.

- ^ Turk, Vito; Stoka, Veronika; Vasiljeva, Olga; Renko, Miha; Sun, Tao; Turk, Boris; Turk, Dušan (January 2012). "Cysteine cathepsins: From structure, function and regulation to new frontiers". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1824 (1): 68–88. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.10.002. PMC 7105208. PMID 22024571.

- ^ a b Nomura T, Katunuma N (February 2005). "Involvement of cathepsins in the invasion, metastasis and proliferation of cancer cells" (PDF). J. Med. Invest. 52 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.2152/jmi.52.1. PMID 15751268.

- ^ Lipton P (October 1999). "Ischemic cell death in brain neurons". Physiol. Rev. 79 (4): 1431–568. doi:10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. PMID 10508238.

- ^ Xu J, Wang H, Ding K, Lu X, Li T, Wang J, Wang C, Wang J (Oct 24, 2013). "Inhibition of cathepsin S produces neuroprotective effects after traumatic brain injury in mice". Mediators of Inflammation. 2013 (2013) 187873. doi:10.1155/2013/187873. PMC 3824312. PMID 24282339.

- ^ Yamashima T (2013). "Reconsider Alzheimer's disease by the 'calpain-cathepsin hypothesis'--a perspective review". Progress in Neurology. 105: 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.02.004. PMID 23499711. S2CID 39292302.

- ^ Raptis SZ, Shapiro SD, Simmons PM, Cheng AM, Pham CT (June 2005). "Serine protease cathepsin G regulates adhesion-dependent neutrophil effector functions by modulating integrin clustering". Immunity. 22 (6): 679–91. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.015. PMID 15963783.

- ^ Chandran K (2005). "Endosomal Proteolysis of the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein Is Necessary for Infection". Science. 308 (5728): 1643–1645. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1643C. doi:10.1126/science.1110656. PMC 4797943. PMID 15831716.

- ^ Im E, Kazlauskas A (March 2007). "The role of cathepsins in ocular physiology and pathology". Exp. Eye Res. 84 (3): 383–8. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2006.05.017. PMID 16893541.

- ^ Hook, Gregory; Hook, Vivian; Kindy, Mark (2011-01-01). "The cysteine protease inhibitor, E64d, reduces brain amyloid-β and improves memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease animal models by inhibiting cathepsin B, but not BACE1, β-secretase activity". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 26 (2): 387–408. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110101. ISSN 1875-8908. PMC 4317342. PMID 21613740.

- ^ Habibollahi, Peiman; Figueiredo, Jose-Luiz; Heidari, Pedram; Dulak, Austin M; Imamura, Yu; Bass, Adam J.; Ogino, Shuji; Chan, Andrew T; Mahmood, Umar (2012). "Optical Imaging with a Cathepsin B Activated Probe for the Enhanced Detection of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma by Dual Channel Fluorescent Upper GI Endoscopy". Theranostics. 2 (2): 227–234. doi:10.7150/thno.4088. PMC 3296470. PMID 22400064.

- ^ Lkhider M, Castino R, Bouguyon E, Isidoro C, Ollivier-Bousquet M (2004). "Cathepsin D released by lactating rat mammary epithelial cells is involved in prolactin cleavage under physiological conditions". Journal of Cell Science. 117 (Pt 21): 5155–5164. doi:10.1242/jcs.01396. PMID 15456852.

- ^ Shi GP, Chapman HA, Bhairi SM, DeLeeuw C, Reddy VY, Weiss SJ (January 1995). "Molecular cloning of human cathepsin O, a novel endoproteinase and homologue of rabbit OC2" (PDF). FEBS Lett. 357 (2): 129–34. Bibcode:1995FEBSL.357..129S. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01349-6. hdl:2027.42/116965. PMID 7805878. S2CID 28099876.

- ^ Gocheva V, Joyce JA (January 2007). "Cysteine cathepsins and the cutting edge of cancer invasion". Cell Cycle. 6 (1): 60–4. doi:10.4161/cc.6.1.3669. PMID 17245112.

- ^ Lutgens E, Lutgens SP, Faber BC, Heeneman S, Gijbels MM, de Winther MP, Frederik P, van der Made I, Daugherty A, Sijbers AM, Fisher A, Long CJ, Saftig P, Black D, Daemen MJ, Cleutjens KB (January 2006). "Disruption of the cathepsin K gene reduces atherosclerosis progression and induces plaque fibrosis but accelerates macrophage foam cell formation". Circulation. 113 (1): 98–107. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561449. PMID 16365196.

- ^ Platt MO, Ankeny RF, Shi GP, Weiss D, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Jo H (March 2007). "Expression of cathepsin K is regulated by shear stress in cultured endothelial cells and is increased in endothelium in human atherosclerosis". Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292 (3): H1479–86. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00954.2006. PMID 17098827.

- ^ Salminen-Mankonen HJ, Morko J, Vuorio E (February 2007). "Role of cathepsin K in normal joints and in the development of arthritis". Curr Drug Targets. 8 (2): 315–23. doi:10.2174/138945007779940188. PMID 17305509.

- ^ Brömme D, Li Z, Barnes M, Mehler E (February 1999). "Human cathepsin V functional expression, tissue distribution, electrostatic surface potential, enzymatic characterization, and chromosomal localization". Biochemistry. 38 (8): 2377–85. doi:10.1021/bi982175f. PMID 10029531.

- ^ Yang M, Zhang Y, Pan J, Sun J, Liu J, Libby P, Sukhova GK, Doria A, Katunuma N, Peroni OD, Guerre-Millo M, Kahn BB, Clement K, Shi GP (August 2007). "Cathepsin L activity controls adipogenesis and glucose tolerance". Nat. Cell Biol. 9 (8): 970–7. doi:10.1038/ncb1623. PMC 3065497. PMID 17643114.

- ^ Bratkovič, et al. (2005). "Affinity selection to papain yields potent peptide inhibitors of cathepsins L, B, H, and K.". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 332 (3): 897–903. Bibcode:2005BBRC..332..897B. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.028. PMID 15913550.

- ^ Mullard, Asher (2016-10-01). "Merck & Co. drops osteoporosis drug odanacatib". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 15 (10): 669. doi:10.1038/nrd.2016.207. ISSN 1474-1784. PMID 27681784. S2CID 10186583.

- ^ Cooley, Brian (July 19, 2022). ""Sorrento Therapeutics Announces the FDA IND Clearance of STI-1558, An Oral M(pro) and Cathepsin L Inhibitor to Treat COVID-19"". Sorrento Therapeutics, Inc. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Li WA, Barry ZT, Cohen JD, Wilder CL, Deeds RJ, Keegan PM, Platt MO (June 2010). "Detection of femtomole quantities of mature cathepsin K with zymography". Anal. Biochem. 401 (1): 91–8. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2010.02.035. PMID 20206119.

- ^ Wilder CL, Park KY, Keegan PM, Platt MO (December 2011). "Manipulating substrate and pH in zymography protocols selectively distinguishes cathepsins K, L, S, and V activity in cells and tissues". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 516 (1): 52–7. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.009. PMC 3221864. PMID 21982919.

- ^ Maver ME, Greco AE (December 1949). "The hydrolysis of nucleoproteins by cathepsins from calf thymus". J. Biol. Chem. 181 (2): 853–60. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)56608-4. PMID 15393803.

- ^ a b Bergmann M, Fruton JS (July 1936). "Regarding the general nature of catheptic enzymes". Science. 84 (2169): 89–90. Bibcode:1936Sci....84...89B. doi:10.1126/science.84.2169.89. PMID 17748131.

- ^ Bergmann M, Fruton JS (June 1, 1937). "On proteolytic enzymes XV. Regarding the general nature of intracellular proteolytic enzymes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 119: 35–46. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)74429-3.

- ^ Anson, M. L. (September 1936). "The estimation of cathepsin with hemoglobin and the partial purification of cathepsin". The Journal of General Physiology. 20 (4): 565–574. doi:10.1085/jgp.20.4.565. PMC 2141516. PMID 19873011.

External links

[edit]- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: A01.010

- Cathepsins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Cathepsin

View on GrokipediaClassification

Cysteine Cathepsins

Cysteine cathepsins represent the largest subfamily of cathepsins, comprising lysosomal proteases belonging to clan CA, family C1 (papain superfamily) of cysteine peptidases, characterized by a catalytic dyad involving a cysteine residue that acts as a nucleophile in peptide bond hydrolysis.[4] These enzymes are optimally active at acidic pH and are involved in intracellular protein turnover, primarily within lysosomes.[4] In humans, there are 11 members: cathepsins B, C, F, H, K, L, O, S, V, W, and X/Z.[4] These proteases originated from the ancient papain superfamily, with ancestral genes tracing back to the last eukaryotic common ancestor through bacterial origins in the first eukaryotic common ancestor.[5] Their diversification arose via multiple gene duplication events during eukaryogenesis, yielding eight ancestral eukaryotic C1A lineages, followed by further duplications in vertebrates that expanded functional diversity.[5] In mammals, tandem gene duplications, particularly of the cathepsin L lineage, contributed to the proliferation of multigene families, enhancing specialization in processes like bone resorption and immune responses.[5] Among these, cathepsin B exhibits a unique hybrid activity as both an endopeptidase and a carboxydipeptidase, enabling it to degrade extracellular matrix components such as collagen IV and activate pro-urokinase-type plasminogen activator.[4] Cathepsin K stands out for its potent collagenolytic activity, playing a key role in degrading bone matrix proteins like collagen and elastin during bone resorption.[4] Cathepsin C functions primarily as an aminopeptidase with dipeptidyl peptidase activity, processing N-terminal dipeptides and activating serine proteases in immune cells, such as granzymes, which is essential for immune cell function.[4] Cathepsin L demonstrates broad endopeptidase specificity, capable of cleaving a wide range of substrates including histones, extracellular matrix proteins, and the invariant chain in antigen presentation.[4] The human cysteine cathepsins, their chromosomal locations, and primary substrates are summarized in the following table:| Cathepsin | Chromosomal Location | Primary Substrates |

|---|---|---|

| B | 8p23.1 | ECM components (e.g., collagen IV), pro-uPA [4] [6] |

| C | 11q14.2 | N-terminal dipeptides, granzymes, proenzymes [4] |

| F | 11q13 | Histones, invariant chain [4] |

| H | 15q25 | N-terminal amino acids, peptides [4] |

| K | 1q21.3 | Collagen, elastin [4] [7] |

| L | 9q21.33 | Histones, ECM proteins, invariant chain [4][8] [9] |

| O | 4q32.1 | Matrix proteins [4][10] [11] |

| S | 1q21.3 | Invariant chain, MHC class II antigens [4][12] |

| V | 9q22.33 | Elastin, ECM proteins [4] [13] |

| W | 11q13.1 | Unknown (cytotoxic role in immune cells) [4][14] |

| X/Z | 20q13.32 | β2 integrin, peptides [4][15] [16] |