Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Exercise

View on Wikipedia

Exercise or working out is physical activity that enhances or maintains fitness and overall health.[1][2] It is performed for various reasons, including weight loss or maintenance, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic skills, improve health,[3] or simply for enjoyment. Many people choose to exercise outdoors where they can congregate in groups, socialize, and improve well-being as well as mental health.[4][5]

In terms of health benefits, usually, 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) of moderate-intensity exercise per week is recommended for reducing the risk of health problems.[6][7][8] At the same time, even doing a small amount of exercise is healthier than doing none. Only doing an hour and a quarter (11 minutes/day) of exercise could reduce the risk of early death, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer.[9][10]

Classification

[edit]Physical exercises are generally grouped into three types, depending on the overall effect they have on the human body:[11]

- Aerobic exercise is any physical activity that uses large muscle groups and causes the body to use more oxygen than it would while resting.[11] The goal of aerobic exercise is to increase cardiovascular endurance.[12] Examples of aerobic exercise include running, cycling, swimming, brisk walking, skipping rope, rowing, hiking, dancing, playing tennis, continuous training, and long distance running.[11]

- Anaerobic exercise, which includes strength and resistance training, can firm, strengthen, and increase muscle mass, as well as improve bone density, balance, and coordination.[11] Examples of strength exercises are push-ups, pull-ups, lunges, squats, bench press. Anaerobic exercise also includes weight training, functional training, Eccentric Training, interval training, sprinting, and high-intensity interval training which increase short-term muscle strength.[11][13]

- Flexibility exercises stretch and lengthen muscles.[11] Activities such as stretching help to improve joint flexibility and keep muscles limber.[11] The goal is to improve the range of motion which can reduce the chance of injury.[11][14]

Physical exercise can also include training that focuses on accuracy, agility, power, and speed.[15]

Types of exercise can also be classified as dynamic or static. 'Dynamic' exercises such as steady running, tend to produce a lowering of the diastolic blood pressure during exercise, due to the improved blood flow. Conversely, static exercise (such as weight-lifting) can cause the systolic pressure to rise significantly, albeit transiently, during the performance of the exercise.[16]

Health effects

[edit]

Physical exercise is important for maintaining physical fitness and can contribute to maintaining a healthy weight, regulating the digestive system, building and maintaining healthy bone density, muscle strength, and joint mobility, promoting physiological well-being, reducing surgical risks, and strengthening the immune system. Some studies indicate that exercise may increase life expectancy and the overall quality of life.[17] People who participate in moderate to high levels of physical exercise have a lower mortality rate compared to individuals who by comparison are not physically active.[18] Moderate levels of exercise have been correlated with preventing aging by reducing inflammatory potential.[19] The majority of the benefits from exercise are achieved with around 3500 metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week, with diminishing returns at higher levels of activity.[20] For example, climbing stairs 10 minutes, vacuuming 15 minutes, gardening 20 minutes, running 20 minutes, and walking or bicycling for transportation 25 minutes on a daily basis would together achieve about 3000 MET minutes a week.[20] A lack of physical activity causes approximately 6% of the burden of disease from coronary heart disease, 7% of type 2 diabetes, 10% of breast cancer, and 10% of colon cancer worldwide.[21] Overall, physical inactivity causes 9% of premature mortality worldwide.[21]

The American-British writer Bill Bryson wrote: "If someone invented a pill that could do for us all that a moderate amount of exercise achieves, it would instantly become the most successful drug in history."[22]

Fitness

[edit]Most people can increase fitness by increasing physical activity levels.[23] Increases in muscle size from resistance training are primarily determined by diet and testosterone.[24] This genetic variation in improvement from training is one of the key physiological differences between elite athletes and the larger population.[25][26] There is evidence that exercising in middle age may lead to better physical ability later in life.[27]

Early motor skills and development is also related to physical activity and performance later in life. Children who are more proficient with motor skills early on are more inclined to be physically active, and thus tend to perform well in sports and have better fitness levels. Early motor proficiency has a positive correlation to childhood physical activity and fitness levels, while less proficiency in motor skills results in a more sedentary lifestyle.[28]

The type and intensity of physical activity performed may have an effect on a person's fitness level. There is some weak evidence that high-intensity interval training may improve a person's VO2 max slightly more than lower intensity endurance training.[29] However, unscientific fitness methods could lead to sports injuries.[citation needed]

Cardiovascular system

[edit]

The beneficial effect of exercise on the cardiovascular system is well documented. There is a direct correlation between physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease, and physical inactivity is an independent risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease. Low levels of physical exercise increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases mortality.[30][31]

Children who participate in physical exercise experience greater loss of body fat and increased cardiovascular fitness.[32] Studies have shown that academic stress in youth increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in later years; however, these risks can be greatly decreased with regular physical exercise.[33]

There is a dose-response relationship between the amount of exercise performed from approximately 700–2000 kcal of energy expenditure per week and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged and elderly men. The greatest potential for reduced mortality is seen in sedentary individuals who become moderately active.

Studies have shown that since heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, regular exercise in aging women leads to healthier cardiovascular profiles.

The most beneficial effects of physical activity on cardiovascular disease mortality can be attained through moderate-intensity activity (40–60% of maximal oxygen uptake, depending on age). After a myocardial infarction, survivors who changed their lifestyle to include regular exercise had higher survival rates. Sedentary people are most at risk for mortality from cardiovascular and all other causes.[34] According to the American Heart Association, exercise reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases, including heart attack and stroke.[31]

Some have suggested that increases in physical exercise might decrease healthcare costs, increase the rate of job attendance, as well as increase the amount of effort women put into their jobs.[35]

Immune system

[edit]Although there have been hundreds of studies on physical exercise and the immune system, there is little direct evidence on its connection to illness.[36] Epidemiological evidence suggests that moderate exercise has a beneficial effect on the human immune system; an effect which is modeled in a J curve. Moderate exercise has been associated with a 29% decreased incidence of upper respiratory tract infections (URTI), but studies of marathon runners found that their prolonged high-intensity exercise was associated with an increased risk of infection occurrence.[36] However, another study did not find the effect. Immune cell functions are impaired following acute sessions of prolonged, high-intensity exercise, and some studies have found that athletes are at a higher risk for infections. Studies have shown that strenuous stress for long durations, such as training for a marathon, can suppress the immune system by decreasing the concentration of lymphocytes.[37] The immune systems of athletes and nonathletes are generally similar. Athletes may have a slightly elevated natural killer cell count and cytolytic action, but these are unlikely to be clinically significant.[36]

Vitamin C supplementation has been associated with a lower incidence of upper respiratory tract infections in marathon runners.[36]

Biomarkers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein, which are associated with chronic diseases, are reduced in active individuals relative to sedentary individuals, and the positive effects of exercise may be due to its anti-inflammatory effects. In individuals with heart disease, exercise interventions lower blood levels of fibrinogen and C-reactive protein, an important cardiovascular risk marker.[38] The depression in the immune system following acute bouts of exercise may be one of the mechanisms for this anti-inflammatory effect.[36]

Cancer

[edit]A systematic review evaluated 45 studies that examined the relationship between physical activity and cancer survival rates. According to the review, "[there] was consistent evidence from 27 observational studies that physical activity is associated with reduced all-cause, breast cancer–specific, and colon cancer–specific mortality. There is currently insufficient evidence regarding the association between physical activity and mortality for survivors of other cancers."[39] Evidence suggests that exercise may positively affect the quality of life in cancer survivors, including factors such as anxiety, self-esteem and emotional well-being.[40] For people with cancer undergoing active treatment, exercise may also have positive effects on health-related quality of life, such as fatigue and physical functioning.[41] This is likely to be more pronounced with higher intensity exercise.[41]

Exercise may contribute to a reduction of cancer-related fatigue in survivors of breast cancer.[42] Although there is only limited scientific evidence on the subject, people with cancer cachexia are encouraged to engage in physical exercise.[43] Due to various factors, some individuals with cancer cachexia have a limited capacity for physical exercise.[44][45] Compliance with prescribed exercise is low in individuals with cachexia and clinical trials of exercise in this population often have high drop-out rates.[44][45]

There is low-quality evidence for an effect of aerobic physical exercises on anxiety and serious adverse events in adults with hematological malignancies.[46] Aerobic physical exercise may result in little to no difference in the mortality, quality of life, or physical functioning.[46] These exercises may result in a slight reduction in depression and reduction in fatigue.[46]

Neurobiological

[edit]

The neurobiological effects of physical exercise involve possible interrelated effects on brain structure, brain function, and cognition.[47][48][49][50] Research in humans has demonstrated that consistent aerobic exercise (e.g., 30 minutes every day) may induce improvements in certain cognitive functions, neuroplasticity and behavioral plasticity; some of these long-term effects may include increased neuron growth, increased neurological activity (e.g., c-Fos and BDNF signaling), improved stress coping, enhanced cognitive control of behavior, improved declarative, spatial, and working memory, and structural and functional improvements in brain structures and pathways associated with cognitive control and memory.[51][52][53] The effects of exercise on cognition may affect academic performance in children and college students, improve adult productivity, preserve cognitive function in old age, prevent or treat certain neurological disorders, and improve overall quality of life.[54][55][56][57]

In healthy adults, aerobic exercise has been shown to induce transient effects on cognition after a single exercise session and persistent effects on cognition following consistent exercise over the course of several months.[47][53][58] People who regularly perform an aerobic exercise (e.g., running, jogging, brisk walking, swimming, and cycling) have greater scores on neuropsychological function and performance tests that measure certain cognitive functions, such as attentional control, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, working memory updating and capacity, declarative memory, spatial memory, and information processing speed.[51][53][58][59][60]

Aerobic exercise has both short and long term effects on mood and emotional states by promoting positive affect, inhibiting negative affect, and decreasing the biological response to acute psychological stress.[58] Aerobic exercise may affect both self-esteem and overall well-being (including sleep patterns) with consistent, long term participation.[61] Regular aerobic exercise may improve symptoms associated with central nervous system disorders and may be used as adjunct therapy for these disorders. There is some evidence of exercise treatment efficacy for major depressive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[55][62][63][64] The American Academy of Neurology's clinical practice guideline for mild cognitive impairment indicates that clinicians should recommend regular exercise (two times per week) to individuals who have been diagnosed with these conditions.[65]

Some preclinical evidence and emerging clinical evidence supports the use of exercise as an adjunct therapy for the treatment and prevention of drug addictions.[66][67][68][69]

Reviews of clinical evidence also support the use of exercise as an adjunct therapy for certain neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.[70][71] Regular exercise may be associated with a lower risk of developing neurodegenerative disorders.[72]Depression

[edit]Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have indicated that exercise has a marked and persistent antidepressant effect in humans,[73][62][74][63][75] an effect believed to be mediated through enhanced BDNF signaling in the brain.[63] Several systematic reviews have analyzed the potential for physical exercise in the treatment of depressive disorders. The 2013 Cochrane Collaboration review on physical exercise for depression noted that, based upon limited evidence, it is more effective than a control intervention and comparable to psychological or antidepressant drug therapies.[75] Three subsequent 2014 systematic reviews that included the Cochrane review in their analysis concluded with similar findings: one indicated that physical exercise is effective as an adjunct treatment (i.e., treatments that are used together) with antidepressant medication;[63] the other two indicated that physical exercise has marked antidepressant effects and recommended the inclusion of physical activity as an adjunct treatment for mild–moderate depression and mental illness in general.[62][74] A 2016 meta-analysis concluded that physical exercise improves overall quality of life in individuals with depression relative to controls. One systematic review noted that yoga may be effective in alleviating symptoms of prenatal depression.[76] Another review asserted that evidence from clinical trials supports the efficacy of physical exercise as a treatment for depression over a 2–4 month period.[51] These benefits have also been noted in old age, with a review conducted in 2019 finding that exercise is an effective treatment for clinically diagnosed depression in older adults.[77]

A 2024 systematic review and network meta-analysis of 218 randomized controlled trials involving over 14,000 participants found that various forms of exercise, including walking or jogging, yoga, resistance training, and mixed aerobic activities, were associated with reductions in depressive symptoms. The review observed that the effects of exercise were comparable to those of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, with more intensive exercise yielding greater benefits. Resistance training was identified as particularly effective for younger individuals, while yoga appeared to be more beneficial for older adults. While confidence in the findings was limited by methodological concerns in the included studies, the review noted that exercise produced significant improvements in symptoms across a wide range of participants and treatment contexts.[73]

Continuous aerobic exercise can induce a transient state of euphoria, colloquially known as a "runner's high" in distance running or a "rower's high" in crew, through the increased biosynthesis of at least three euphoriant neurochemicals: anandamide (an endocannabinoid),[78] β-endorphin (an endogenous opioid),[79] and phenethylamine (a trace amine and amphetamine analog).[80][81][82]

Concussion

[edit]Supervised aerobic exercise without a risk of re-injury (falling, getting hit on the head) is prescribed as treatment for acute concussion.[83] Some exercise interventions may also prevent sport-related concussion.[84]

Sleep

[edit]Preliminary evidence from a 2012 review indicated that physical training for up to four months may increase sleep quality in adults over 40 years of age.[85] A 2010 review suggested that exercise generally improved sleep for most people, and may help with insomnia, but there is insufficient evidence to draw detailed conclusions about the relationship between exercise and sleep.[86] A 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that exercise can improve sleep quality in people with insomnia.[87]

Libido

[edit]One 2013 study found that exercising improved sexual arousal problems related to antidepressant use.[88]

Respiratory system

[edit]People who participate in physical exercise experience increased cardiovascular fitness.[medical citation needed] There is some level of concern about additional exposure to air pollution when exercising outdoors, especially near traffic.[89]

Mechanism of effects

[edit]Skeletal muscle

[edit]Resistance training and subsequent consumption of a protein-rich meal promotes muscle hypertrophy and gains in muscle strength by stimulating myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and inhibiting muscle protein breakdown (MPB).[90][91] The stimulation of muscle protein synthesis by resistance training occurs via phosphorylation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and subsequent activation of mTORC1, which leads to protein biosynthesis in cellular ribosomes via phosphorylation of mTORC1's immediate targets (the p70S6 kinase and the translation repressor protein 4EBP1).[90][92] The suppression of muscle protein breakdown following food consumption occurs primarily via increases in plasma insulin.[90][93][94] Similarly, increased muscle protein synthesis (via activation of mTORC1) and suppressed muscle protein breakdown (via insulin-independent mechanisms) has also been shown to occur following ingestion of β-hydroxy β-methylbutyric acid.[90][93][94][95]

Aerobic exercise induces mitochondrial biogenesis and an increased capacity for oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria of skeletal muscle, which is one mechanism by which aerobic exercise enhances submaximal endurance performance.[96][90][97] These effects occur via an exercise-induced increase in the intracellular AMP:ATP ratio, thereby triggering the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) which subsequently phosphorylates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis.[90][97][98]

• PA: phosphatidic acid

• mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin

• AMP: adenosine monophosphate

• ATP: adenosine triphosphate

• AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase

• PGC-1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α

• S6K1: p70S6 kinase

• 4EBP1: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1

• eIF4E: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

• RPS6: ribosomal protein S6

• eEF2: eukaryotic elongation factor 2

• RE: resistance exercise; EE: endurance exercise

• Myo: myofibrillar; Mito: mitochondrial

• AA: amino acids

• HMB: β-hydroxy β-methylbutyric acid

• ↑ represents activation

• Τ represents inhibition

Other peripheral organs

[edit]

Developing research has demonstrated that many of the benefits of exercise are mediated through the role of skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ. That is, contracting muscles release multiple substances known as myokines which promote the growth of new tissue, tissue repair, and multiple anti-inflammatory functions, which in turn reduce the risk of developing various inflammatory diseases.[112] Exercise reduces levels of cortisol, which causes many health problems, both physical and mental.[113] Endurance exercise before meals lowers blood glucose more than the same exercise after meals.[114] There is evidence that vigorous exercise (90–95% of VO2 max) induces a greater degree of physiological cardiac hypertrophy than moderate exercise (40 to 70% of VO2 max), but it is unknown whether this has any effects on overall morbidity and/or mortality.[115] Both aerobic and anaerobic exercise work to increase the mechanical efficiency of the heart by increasing cardiac volume (aerobic exercise), or myocardial thickness (strength training). Ventricular hypertrophy, the thickening of the ventricular walls, is generally beneficial and healthy if it occurs in response to exercise.

Central nervous system

[edit]The effects of physical exercise on the central nervous system may be mediated in part by specific neurotrophic factor hormones released into the blood by muscles, including BDNF, IGF-1, and VEGF.[116][117][118]

Public health measures

[edit]Community-wide and school campaigns are often used in an attempt to increase a population's level of physical activity. Studies to determine the effectiveness of these types of programs need to be interpreted cautiously as the results vary.[23] There is some evidence that certain types of exercise programmes for older adults, such as those involving gait, balance, co-ordination and functional tasks, can improve balance.[119] Following progressive resistance training, older adults also respond with improved physical function.[120] Brief interventions promoting physical activity may be cost-effective, however this evidence is weak and there are variations between studies.[121]

Environmental approaches appear promising: signs that encourage the use of stairs, as well as community campaigns, may increase exercise levels.[122] The city of Bogotá, Colombia, for example, blocks off 113 kilometers (70 mi) of roads on Sundays and holidays to make it easier for its citizens to get exercise. Such pedestrian zones are part of an effort to combat chronic diseases and to maintain a healthy BMI.[123]

Parents can promote physical activity by modelling healthy levels of physical activity or by encouraging physical activity.[124] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, children and adolescents should do 60 minutes or more of physical activity each day.[125] Implementing physical exercise in the school system and ensuring an environment in which children can reduce barriers to maintain a healthy lifestyle is essential.

The European Commission's Directorate-General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) has dedicated programs and funds for Health Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA) projects[126] within its Horizon 2020 and Erasmus+ program, as research showed that too many Europeans are not physically active enough. Financing is available for increased collaboration between players active in this field across the EU and around the world, the promotion of HEPA in the EU and its partner countries, and the European Sports Week. The DG EAC regularly publishes a Eurobarometer on sport and physical activity.

Exercise trends

[edit]Worldwide there has been a large shift toward less physically demanding work.[127] This has been accompanied by increasing use of mechanized transportation, a greater prevalence of labor-saving technology in the home, and fewer active recreational pursuits.[127] Personal lifestyle changes, however, can correct the lack of physical exercise.[medical citation needed]

Research published in 2015 suggests that incorporating mindfulness into physical exercise interventions increases exercise adherence and self-efficacy, and also has positive effects both psychologically and physiologically.[128]

- Sports activities for exercising

-

Running helps in achieving physical fitness.[129]

-

Swimming as an exercise tones muscles and builds strength.[131]

-

Athletics (ex. pole vault) as a form of exercise

-

Football as an exercise

Social and cultural variation

[edit]Exercising looks different in every country, as do the motivations behind exercising.[4] In some countries, people exercise primarily indoors (such as at home or health clubs), while in others, people primarily exercise outdoors. People may exercise for personal enjoyment, health and well-being, social interactions, competition or training, etc. These differences could potentially be attributed to a variety of reasons including geographic location and social tendencies.

In Colombia, for example, citizens value and celebrate the outdoor environments of their country. In many instances, they use outdoor activities as social gatherings to enjoy nature and their communities. In Bogotá, Colombia, a 70-mile stretch of road known as the Ciclovía is shut down each Sunday for bicyclists, runners, rollerbladers, skateboarders and other exercisers to work out and enjoy their surroundings.[132]

Similarly to Colombia, citizens of Cambodia tend to exercise socially outside. In this country, public gyms have become quite popular. People will congregate at these outdoor gyms not only to use the public facilities, but also to organize aerobics and dance sessions, which are open to the public.[133]

Sweden has also begun developing outdoor gyms, called utegym. These gyms are free to the public and are often placed in beautiful, picturesque environments. People will swim in rivers, use boats, and run through forests to stay healthy and enjoy the natural world around them. This works particularly well in Sweden due to its geographical location.[134]

Exercise in some areas of China, particularly among those who are retired, seems to be socially grounded. In the mornings, square dances are held in public parks; these gatherings may include Latin dancing, ballroom dancing, tango, or even the jitterbug. Dancing in public allows people to interact with those with whom they would not normally interact, allowing for both health and social benefits.[135]

These sociocultural variations in physical exercise show how people in different geographic locations and social climates have varying motivations and methods of exercising. Physical exercise can improve health and well-being, as well as enhance community ties and appreciation of natural beauty.[4]

Adherence

[edit]Adhering or staying consistent with an exercise program can be challenging for many people.[136] Studies have identified many different factors. Some factors include why a person is exercising (e.g, health, social), what types of exercises or how the exercise program is structured, whether or not professionals are involved in the program, education related to exercise and health, monitoring and progress made in exercise program, goals setting, and involved a person is in choosing the exercise program and setting goals.[137]

Nutrition and recovery

[edit]Proper nutrition is as important to health as exercise. When exercising, it becomes even more important to have a good diet to ensure that the body has the correct ratio of macronutrients while providing ample micronutrients, to aid the body with the recovery process following strenuous exercise.[138]

Active recovery is recommended after participating in physical exercise because it removes lactate from the blood more quickly than inactive recovery. Removing lactate from circulation allows for an easy decline in body temperature, which can also benefit the immune system, as an individual may be vulnerable to minor illnesses if the body temperature drops too abruptly after physical exercise.[139] Exercise physiologists recommend the "4-Rs framework":[140]

- Rehydration

- Replacing any fluid and electrolyte deficits

- Refuel

- Consuming carbohydrates to replenish muscle and liver glycogen

- Repair

- Consuming high-quality protein sources with additional supplementation of creatine monohydrate

- Rest

- Getting long and high-quality sleep after exercise, additionally improved by consuming casein proteins, antioxidant-rich fruits, and high-glycemic-index meals

Exercise has an effect on appetite, but whether it increases or decreases appetite varies from individual to individual, and is affected by the intensity and duration of the exercise.[141]

Excessive exercise

[edit]Overtraining occurs when a person exceeds their body's ability to recover from strenuous exercise.[142] Overtraining can be described as a point at which a person may have a decrease in performance or plateau as a result of failure to perform at a certain level or training-load consistently; a load which exceeds their recovery capacity.[143] People who are overtrained cease making progress, and can even begin to lose strength and fitness. Overtraining is also known as chronic fatigue, burnout, and overstress in athletes.[144][145]

It is suggested that there are different forms of overtraining. Firstly, "monotonous program overtraining" suggests that repetition of the same movement, such as certain weight lifting and baseball batting, can cause performance plateau due to an adaption of the central nervous system, which results from a lack of stimulation.[143] A second example of overtraining is described as "chronic overwork-type," wherein the subject may be training with too high intensity or high volume and not allowing sufficient recovery time for the body.[143]

Up to 10% of elite endurance athletes and 10% of American college swimmers are affected by overtraining syndrome (i.e., unexplained underperformance for approximately 2 weeks, even after having adequate resting time).[146]History

[edit]This article is missing information about times and places when exercise was viewed negatively. (August 2021) |

The benefits of exercise have been known since antiquity. Dating back to 65 BCE, it was Marcus Cicero, Roman politician and lawyer, who stated: "It is exercise alone that supports the spirits, and keeps the mind in vigor."[147] Exercise was also seen to be valued later in history during the Early Middle Ages as a means of survival by the Germanic peoples of Northern Europe.[148]

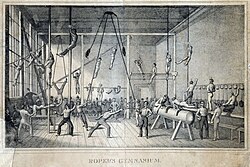

More recently, exercise was regarded as a beneficial force in the 19th century. In 1858, Archibald MacLaren opened a gymnasium at the University of Oxford and instituted a training regimen for Major Frederick Hammersley and 12 non-commissioned officers.[149] This regimen was assimilated into the training of the British Army, which formed the Army Gymnastic Staff in 1860 and made sport an important part of military life.[150][151][152] Several mass exercise movements were started in the early twentieth century as well. The first and most significant of these in the UK was the Women's League of Health and Beauty, founded in 1930 by Mary Bagot Stack, that had 166,000 members in 1937.[153]

The link between physical health and exercise (or lack of it) was further established in 1949 and reported in 1953 by a team led by Jerry Morris.[154][155] Morris noted that men of similar social class and occupation (bus conductors versus bus drivers) had markedly different rates of heart attacks, depending on the level of exercise they got: bus drivers had a sedentary occupation and a higher incidence of heart disease, while bus conductors were forced to move continually and had a lower incidence of heart disease.[155]

Other animals

[edit]Animals like chimpanzees, orangutans, gorillas and bonobos, which are closely related to humans, without ill effect engage in considerably less physical activity than is required for human health, raising the question of how this is biochemically possible.[156]

Studies of animals indicate that physical activity may be more adaptable than changes in food intake to regulate energy balance.[157]

Mice having access to activity wheels engaged in voluntary exercise and increased their propensity to run as adults.[158] Artificial selection of mice exhibited significant heritability in voluntary exercise levels,[159] with "high-runner" breeds having enhanced aerobic capacity,[160] hippocampal neurogenesis,[161] and skeletal muscle morphology.[162]

The effects of exercise training appear to be heterogeneous across non-mammalian species. As examples, exercise training of salmon showed minor improvements of endurance,[163] and a forced swimming regimen of yellowtail amberjack and rainbow trout accelerated their growth rates and altered muscle morphology favorable for sustained swimming.[164][165] Crocodiles, alligators, and ducks showed elevated aerobic capacity following exercise training.[166][167][168] No effect of endurance training was found in most studies of lizards,[166][169] although one study did report a training effect.[170] In lizards, sprint training had no effect on maximal exercise capacity,[170] and muscular damage from over-training occurred following weeks of forced treadmill exercise.[169]

See also

[edit]- Active living

- Behavioural change theories

- Bodybuilding

- Cyclability

- Exercise hypertension

- Exercise intensity

- Exercise intolerance

- Exercise-induced anaphylaxis

- Exercise-induced asthma

- Exercise-induced nausea

- Green exercise

- Kinesiology

- Metabolic equivalent

- Neurobiological effects of physical exercise

- Non-exercise associated thermogenesis

- Supercompensation

- Unilateral training

- Walkability

- Warming up

References

[edit]- ^ Kylasov A, Gavrov S (2011). Diversity Of Sport: non-destructive evaluation. Paris: UNESCO: Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. pp. 462–91. ISBN 978-5-89317-227-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Liberman, Daniel (2020). Exercised. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-593-29539-7.

- ^ "7 great reasons why exercise matters". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Bergstrom K, Muse T, Tsai M, Strangio S (19 January 2011). "Fitness for Foreigners". Slate. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Deslandes A, Moraes H, Ferreira C, Veiga H, Silveira H, Mouta R, et al. (2009). "Exercise and mental health: many reasons to move". Neuropsychobiology. 59 (4): 191–198. doi:10.1159/000223730. PMID 19521110. S2CID 14580554.

- ^ "Physical activity guidelines for adults aged 19 to 64". NHS. 25 January 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "How much physical activity do adults need?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Physical activity". WHO. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Small amounts of exercise protect against early death, heart disease and cancer". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 14 August 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_59256. S2CID 260908783.

- ^ Garcia, Leandro; Pearce, Matthew; Abbas, Ali; et al. (28 February 2023). "Non-occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality outcomes: a dose–response meta-analysis of large prospective studies". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 57 (15): 979–989. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-105669. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 10423495. PMID 36854652.

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (June 2006). "Your Guide to Physical Activity and Your Heart" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^ Wilmore JH (May 2003). "Aerobic exercise and endurance: improving fitness for health benefits". The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 31 (5): 45–51. doi:10.3810/psm.2003.05.367. PMID 20086470. S2CID 2253889.

- ^ de Vos NJ, Singh NA, Ross DA, Stavrinos TM, Orr R, Fiatarone Singh MA (May 2005). "Optimal load for increasing muscle power during explosive resistance training in older adults". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 60 (5): 638–647. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.5.638. PMID 15972618.

- ^ O'Connor DM, Crowe MJ, Spinks WL (March 2006). "Effects of static stretching on leg power during cycling". The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 46 (1): 52–56. PMID 16596099.

- ^ "What Is Fitness?" (PDF). The CrossFit Journal. October 2002. p. 4. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ de Souza Nery S, Gomides RS, da Silva GV, de Moraes Forjaz CL, Mion D, Tinucci T (March 2010). "Intra-arterial blood pressure response in hypertensive subjects during low- and high-intensity resistance exercise". Clinics. 65 (3): 271–277. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322010000300006. PMC 2845767. PMID 20360917.

- ^ Gremeaux V, Gayda M, Lepers R, Sosner P, Juneau M, Nigam A (December 2012). "Exercise and longevity". Maturitas. 73 (4): 312–317. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.09.012. PMID 23063021.

- ^ United States Department Of Health And Human Services (1996). "Physical Activity and Health". United States Department of Health. ISBN 978-1-4289-2794-0.

- ^ Woods JA, Wilund KR, Martin SA, Kistler BM (February 2012). "Exercise, inflammation and aging". Aging and Disease. 3 (1): 130–140. PMC 3320801. PMID 22500274.

- ^ a b Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford JE, Afshin A, Estep K, et al. (August 2016). "Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". BMJ. 354 i3857. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3857. PMC 4979358. PMID 27510511.

- ^ a b Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT (July 2012). "Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy". Lancet. 380 (9838): 219–229. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. PMC 3645500. PMID 22818936.

- ^ Bryson, Bill (2019). The Body: A Guide for Occupants. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-85752-240-5.

- ^ a b Neil-Sztramko SE, Caldwell H, Dobbins M (September 2021). "School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (9) CD007651. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub3. PMC 8459921. PMID 34555181.

- ^ Hubal MJ, Gordish-Dressman H, Thompson PD, et al. (June 2005). "Variability in muscle size and strength gain after unilateral resistance training". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 37 (6): 964–972. PMID 15947721.

- ^ Brutsaert TD, Parra EJ (April 2006). "What makes a champion? Explaining variation in human athletic performance". Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 151 (2–3): 109–123. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2005.12.013. PMID 16448865. S2CID 13711090.

- ^ Geddes L (28 July 2007). "Superhuman". New Scientist. pp. 35–41.

- ^ "Being active combats risk of functional problems".

- ^ Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Dorn JM, Jones KE, Kondilis VA (December 2006). "The relationship between motor proficiency and physical activity in children". Pediatrics. 118 (6): e1758 – e1765. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0742. PMID 17142498. S2CID 41653923.

- ^ Milanović Z, Sporiš G, Weston M (October 2015). "Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIT) and Continuous Endurance Training for VO2max Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials" (PDF). Sports Medicine. 45 (10): 1469–1481. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0. PMID 26243014. S2CID 41092016.

- ^ Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS (March 2006). "Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence". CMAJ. 174 (6): 801–809. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051351. PMC 1402378. PMID 16534088.

- ^ a b "American Heart Association Recommendations for Physical Activity in Adults". American Heart Association. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Lumeng JC (March 2006). "Small-group physical education classes result in important health benefits". The Journal of Pediatrics. 148 (3): 418–419. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.025. PMID 17243298.

- ^ Ahaneku JE, Nwosu CM, Ahaneku GI (June 2000). "Academic stress and cardiovascular health". Academic Medicine. 75 (6): 567–568. doi:10.1097/00001888-200006000-00002. PMID 10875499.

- ^ Fletcher GF, Balady G, Blair SN, Blumenthal J, Caspersen C, Chaitman B, et al. (August 1996). "Statement on exercise: benefits and recommendations for physical activity programs for all Americans. A statement for health professionals by the Committee on Exercise and Cardiac Rehabilitation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association". Circulation. 94 (4): 857–862. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.94.4.857. PMID 8772712. S2CID 2392781.

- ^ Reed JL, Prince SA, Cole CA, Fodor JG, Hiremath S, Mullen KA, et al. (December 2014). "Workplace physical activity interventions and moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity levels among working-age women: a systematic review protocol". Systematic Reviews. 3 (1) 147. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-147. PMC 4290810. PMID 25526769.

- ^ a b c d e Gleeson M (August 2007). "Immune function in sport and exercise". Journal of Applied Physiology. 103 (2): 693–699. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00008.2007. PMID 17303714. S2CID 18112931.

- ^ Brolinson PG, Elliott D (July 2007). "Exercise and the immune system". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 26 (3): 311–319. doi:10.1097/01893697-200220010-00013. PMID 17826186. S2CID 91074779.

- ^ Swardfager W, Herrmann N, Cornish S, Mazereeuw G, Marzolini S, Sham L, Lanctôt KL (April 2012). "Exercise intervention and inflammatory markers in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis". American Heart Journal. 163 (4): 666–676. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.12.017. PMID 22520533.

- ^ Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM (June 2012). "Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 104 (11): 815–840. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs207. PMC 3465697. PMID 22570317.

- ^ Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O, Gotay CC, Snyder C (August 2012). "Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (8) CD007566. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007566.pub2. PMC 7387117. PMID 22895961.

- ^ a b Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O (August 2012). "Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (8) CD008465. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008465.pub2. PMC 7389071. PMID 22895974.

- ^ Meneses-Echávez JF, González-Jiménez E, Ramírez-Vélez R (February 2015). "Effects of supervised exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cancer. 15 (1) 77. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1069-4. PMC 4364505. PMID 25885168.

- ^ Grande AJ, Silva V, Maddocks M (September 2015). "Exercise for cancer cachexia in adults: Executive summary of a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review". Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 6 (3): 208–211. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12055. PMC 4575551. PMID 26401466.

- ^ a b Sadeghi M, Keshavarz-Fathi M, Baracos V, Arends J, Mahmoudi M, Rezaei N (July 2018). "Cancer cachexia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 127: 91–104. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.05.006. PMID 29891116. S2CID 48363786.

- ^ a b Solheim TS, Laird BJ, Balstad TR, Bye A, Stene G, Baracos V, et al. (September 2018). "Cancer cachexia: rationale for the MENAC (Multimodal-Exercise, Nutrition and Anti-inflammatory medication for Cachexia) trial". BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 8 (3): 258–265. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001440. hdl:10852/73081. PMID 29440149. S2CID 3318359.

- ^ a b c Knips L, Bergenthal N, Streckmann F, Monsef I, Elter T, Skoetz N, et al. (Cochrane Hematological Malignancies Group) (January 2019). "Aerobic physical exercise for adult patients with haematological malignancies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD009075. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009075.pub3. PMC 6354325. PMID 30702150.

- ^ a b Erickson KI, Hillman CH, Kramer AF (August 2015). "Physical activity, brain, and cognition". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 4: 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.01.005. S2CID 54301951.

- ^ Paillard T, Rolland Y, de Souto Barreto P (July 2015). "Protective Effects of Physical Exercise in Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: A Narrative Review". J Clin Neurol. 11 (3): 212–219. doi:10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.212. PMC 4507374. PMID 26174783.

- ^ McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD (January 2014). "The neuropathology of sport". Acta Neuropathol. 127 (1): 29–51. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1230-6. PMC 4255282. PMID 24366527.

- ^ Denham J, Marques FZ, O'Brien BJ, Charchar FJ (February 2014). "Exercise: putting action into our epigenome". Sports Med. 44 (2): 189–209. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0114-1. PMID 24163284. S2CID 30210091.

- ^ a b c Gomez-Pinilla F, Hillman C (January 2013). "The influence of exercise on cognitive abilities". Comprehensive Physiology. 3 (1): 403–428. doi:10.1002/cphy.c110063. ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4. PMC 3951958. PMID 23720292.

- ^ Buckley J, Cohen JD, Kramer AF, McAuley E, Mullen SP (2014). "Cognitive control in the self-regulation of physical activity and sedentary behavior". Front Hum Neurosci. 8: 747. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00747. PMC 4179677. PMID 25324754.

- ^ a b c Cox EP, O'Dwyer N, Cook R, Vetter M, Cheng HL, Rooney K, O'Connor H (August 2016). "Relationship between physical activity and cognitive function in apparently healthy young to middle-aged adults: A systematic review". J. Sci. Med. Sport. 19 (8): 616–628. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.09.003. PMID 26552574.

- ^ CDC (1 August 2023). "Benefits of Physical Activity". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Richards J, Ward PB, Stubbs B (July 2016). "Exercise improves physical and psychological quality of life in people with depression: A meta-analysis including the evaluation of control group response". Psychiatry Res. 241: 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.054. PMID 27155287. S2CID 4787287.

- ^ Pratali L, Mastorci F, Vitiello N, Sironi A, Gastaldelli A, Gemignani A (November 2014). "Motor Activity in Aging: An Integrated Approach for Better Quality of Life". International Scholarly Research Notices. 2014 257248. doi:10.1155/2014/257248. PMC 4897547. PMID 27351018.

- ^ Mandolesi L, Polverino A, Montuori S, Foti F, Ferraioli G, Sorrentino P, Sorrentino G (27 April 2018). "Effects of Physical Exercise on Cognitive Functioning and Wellbeing: Biological and Psychological Benefits". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 509. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00509. PMC 5934999. PMID 29755380.

- ^ a b c Basso JC, Suzuki WA (March 2017). "The Effects of Acute Exercise on Mood, Cognition, Neurophysiology, and Neurochemical Pathways: A Review". Brain Plasticity. 2 (2): 127–152. doi:10.3233/BPL-160040. PMC 5928534. PMID 29765853.

- ^ "Exercise and mental health". betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ "Exercise and Mental Health". Exercise Psychology: 93–94. 2013. doi:10.5040/9781492595502.part-002. ISBN 978-1-4925-9550-2.

- ^ "10 great reasons to love aerobic exercise". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T (2014). "Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review". Scand J Med Sci Sports. 24 (2): 259–272. doi:10.1111/sms.12050. PMID 23362828. S2CID 29351791.

- ^ a b c d Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, Carta MG (2014). "Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review". CNS Spectr. 19 (6): 496–508. doi:10.1017/S1092852913000953. PMID 24589012. S2CID 32304140.

- ^ Den Heijer AE, Groen Y, Tucha L, Fuermaier AB, Koerts J, Lange KW, Thome J, Tucha O (July 2016). "Sweat it out? The effects of physical exercise on cognition and behavior in children and adults with ADHD: a systematic literature review". J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 124 (Suppl 1): 3–26. doi:10.1007/s00702-016-1593-7. PMC 5281644. PMID 27400928.

- ^ Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius T, Ganguli M, Gloss D, Gronseth GS, Marson D, Pringsheim T, Day GS, Sager M, Stevens J, Rae-Grant A (January 2018). "Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment – Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. Special article. 90 (3): 126–135. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826. PMC 5772157. PMID 29282327.

- ^ Carroll ME, Smethells JR (February 2016). "Sex Differences in Behavioral Dyscontrol: Role in Drug Addiction and Novel Treatments". Front. Psychiatry. 6: 175. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00175. PMC 4745113. PMID 26903885.

- ^ Lynch WJ, Peterson AB, Sanchez V, Abel J, Smith MA (September 2013). "Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: a neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 37 (8): 1622–1644. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.011. PMC 3788047. PMID 23806439.

- ^ Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

- ^ Linke SE, Ussher M (2015). "Exercise-based treatments for substance use disorders: evidence, theory, and practicality". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 41 (1): 7–15. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.976708. PMC 4831948. PMID 25397661.

- ^ Farina N, Rusted J, Tabet N (January 2014). "The effect of exercise interventions on cognitive outcome in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review". Int Psychogeriatr. 26 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001385. PMID 23962667. S2CID 24936334.

- ^ Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, Herd CP, Clarke CE, Stowe R, Shah L, Sackley CM, Deane KH, Wheatley K, Ives N (September 2013). "Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 (9) CD002817. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub4. PMC 7120224. PMID 24018704.

- ^ Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, Veerman JL (May 2014). "Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". BMC Public Health. 14 510. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-510. PMC 4064273. PMID 24885250.

- ^ a b Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, Del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D, Smith JJ, Mahoney J, Spathis J, Moresi M, Pagano R, Pagano L, Vasconcellos R, Arnott H, Varley B, Parker P, Biddle S, Lonsdale C (14 February 2024). "Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 384 e075847. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847. PMC 10870815. PMID 38355154.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Curtis J, Ward PB (2014). "Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Clin Psychiatry. 75 (9): 964–974. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08765. PMID 24813261.

- ^ a b Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, McMurdo M, Mead GE (September 2013). "Exercise for depression". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013 (9) CD004366. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. PMC 9721454. PMID 24026850.

- ^ Gong H, Ni C, Shen X, Wu T, Jiang C (February 2015). "Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 15 14. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0393-1. PMC 4323231. PMID 25652267.

- ^ Miller KJ, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Areerob P, Hennessy D, Mesagno C, Grace F (2020). "Comparative effectiveness of three exercise types to treat clinical depression in older adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Ageing Research Reviews. 58 100999. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2019.100999. hdl:1959.17/172086. PMID 31837462. S2CID 209179889.

- ^ Tantimonaco M, Ceci R, Sabatini S, Catani MV, Rossi A, Gasperi V, Maccarrone M (July 2014). "Physical activity and the endocannabinoid system: an overview". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 71 (14): 2681–2698. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1575-6. PMC 11113821. PMID 24526057. S2CID 14531019.

- ^ Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD (June 2011). "Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 180 (2): 319–325. doi:10.1007/s11845-010-0633-9. PMID 21076975. S2CID 40951545.

- ^ Szabo A, Billett E, Turner J (October 2001). "Phenylethylamine, a possible link to the antidepressant effects of exercise?". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 35 (5): 342–343. doi:10.1136/bjsm.35.5.342. PMC 1724404. PMID 11579070.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Berry MD (January 2007). "The potential of trace amines and their receptors for treating neurological and psychiatric diseases". Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 2 (1): 3–19. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. PMID 18473983. S2CID 7127324.

- ^ De Luigi, Arthur J.; Bell, Kathleen R.; Bramhall, Joe P.; Choe, Meeryo; Dec, Katherine; Finnoff, Jonathan T.; Halstead, Mark; Herring, Stanley A.; Matuszak, Jason; Raksin, P. B.; Swanson, Jennifer; Millett, Carolyn (2023). "Consensus statement: An evidence-based review of exercise, rehabilitation, rest, and return to activity protocols for the treatment of concussion and mild traumatic brain injury". PM&R. 15 (12): 1605–1642. doi:10.1002/pmrj.13070. ISSN 1934-1563. PMID 37794736.

- ^ Ivanic, Branimir; Cronström, Anna; Johansson, Kajsa; Ageberg, Eva (6 September 2024). "Efficacy of exercise interventions on prevention of sport-related concussion and related outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 58 (23): bjsports–2024–108260. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2024-108260. ISSN 1473-0480. PMC 11672061. PMID 39242177.

- ^ Yang PY, Ho KH, Chen HC, Chien MY (2012). "Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: a systematic review". Journal of Physiotherapy. 58 (3): 157–163. doi:10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70106-6. PMID 22884182.

- ^ Buman MP, King AC (2010). "Exercise as a Treatment to Enhance Sleep". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 31 (5): 514. doi:10.1177/1559827610375532. S2CID 73314918.

- ^ Banno M, Harada Y, Taniguchi M, Tobita R, Tsujimoto H, Tsujimoto Y, et al. (2018). "Exercise can improve sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PeerJ. 6 e5172. doi:10.7717/peerj.5172. PMC 6045928. PMID 30018855.

- ^ Lorenz TA, Meston CM (June 2012). "Acute exercise improves physical sexual arousal in women taking antidepressants". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 43 (3): 352–361. doi:10.1007/s12160-011-9338-1. PMC 3422071. PMID 22403029.

- ^ Laeremans M, Dons E, Avila-Palencia I, Carrasco-Turigas G, Orjuela-Mendoza JP, Anaya-Boig E, et al. (September 2018). "Black Carbon Reduces the Beneficial Effect of Physical Activity on Lung Function". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 50 (9): 1875–1881. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001632. hdl:10044/1/63478. PMID 29634643. S2CID 207183760.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brook MS, Wilkinson DJ, Phillips BE, Perez-Schindler J, Philp A, Smith K, Atherton PJ (January 2016). "Skeletal muscle homeostasis and plasticity in youth and ageing: impact of nutrition and exercise". Acta Physiologica. 216 (1): 15–41. doi:10.1111/apha.12532. PMC 4843955. PMID 26010896.

- ^ a b c Phillips SM (May 2014). "A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy". Sports Medicine. 44 (Suppl 1): S71 – S77. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0152-3. PMC 4008813. PMID 24791918.

- ^ Brioche T, Pagano AF, Py G, Chopard A (August 2016). "Muscle wasting and aging: Experimental models, fatty infiltrations, and prevention" (PDF). Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 50: 56–87. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2016.04.006. PMID 27106402. S2CID 29717535.

- ^ a b Wilkinson DJ, Hossain T, Hill DS, et al. (June 2013). "Effects of leucine and its metabolite β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate on human skeletal muscle protein metabolism". The Journal of Physiology. 591 (11): 2911–2923. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.253203. PMC 3690694. PMID 23551944.

- ^ a b Wilkinson DJ, Hossain T, Limb MC, et al. (December 2018). "Impact of the calcium form of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate upon human skeletal muscle protein metabolism". Clinical Nutrition. 37 (6 Pt A): 2068–2075. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.09.024. PMC 6295980. PMID 29097038.

- ^ Phillips SM (July 2015). "Nutritional supplements in support of resistance exercise to counter age-related sarcopenia". Advances in Nutrition. 6 (4): 452–460. doi:10.3945/an.115.008367. PMC 4496741. PMID 26178029.

- ^ Wibom R, Hultman E, Johansson M, Matherei K, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Schantz PG (November 1992). "Adaptation of mitochondrial ATP production in human skeletal muscle to endurance training and detraining". Journal of Applied Physiology. 73 (5): 2004–2010. doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.2004. PMID 1474078.

- ^ a b Boushel R, Lundby C, Qvortrup K, Sahlin K (October 2014). "Mitochondrial plasticity with exercise training and extreme environments". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 42 (4): 169–174. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000025. PMID 25062000. S2CID 39267910.

- ^ Valero T (2014). "Mitochondrial biogenesis: pharmacological approaches". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 20 (35): 5507–5509. doi:10.2174/138161282035140911142118. hdl:10454/13341. PMID 24606795.

- ^ Lipton JO, Sahin M (October 2014). "The neurology of mTOR". Neuron. 84 (2): 275–291. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. PMC 4223653. PMID 25374355.

Figure 2: The mTOR Signaling Pathway - ^ a b Wang E, Næss MS, Hoff J, Albert TL, Pham Q, Richardson RS, Helgerud J (April 2014). "Exercise-training-induced changes in metabolic capacity with age: the role of central cardiovascular plasticity". Age. 36 (2): 665–676. doi:10.1007/s11357-013-9596-x. PMC 4039249. PMID 24243396.

- ^ Potempa K, Lopez M, Braun LT, Szidon JP, Fogg L, Tincknell T (January 1995). "Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients". Stroke. 26 (1): 101–105. doi:10.1161/01.str.26.1.101. PMID 7839377.

- ^ Wilmore JH, Stanforth PR, Gagnon J, Leon AS, Rao DC, Skinner JS, Bouchard C (July 1996). "Endurance exercise training has a minimal effect on resting heart rate: the Heritage Study". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 28 (7): 829–835. doi:10.1097/00005768-199607000-00009. PMID 8832536.

- ^ Carter JB, Banister EW, Blaber AP (2003). "Effect of endurance exercise on autonomic control of heart rate". Sports Medicine. 33 (1): 33–46. doi:10.2165/00007256-200333010-00003. PMID 12477376. S2CID 40393053.

- ^ Chen CY, Dicarlo SE (January 1998). "Endurance exercise training-induced resting Bradycardia: A brief review". Sports Medicine, Training and Rehabilitation. 8 (1): 37–77. doi:10.1080/15438629709512518.

- ^ Crewther BT, Heke TL, Keogh JW (February 2013). "The effects of a resistance-training program on strength, body composition and baseline hormones in male athletes training concurrently for rugby union 7's". The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 53 (1): 34–41. PMID 23470909.

- ^ Schoenfeld BJ (June 2013). "Postexercise hypertrophic adaptations: a reexamination of the hormone hypothesis and its applicability to resistance training program design". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 27 (6): 1720–1730. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828ddd53. PMID 23442269. S2CID 25068522.

- ^ Dalgas U, Stenager E, Lund C, Rasmussen C, Petersen T, Sørensen H, et al. (July 2013). "Neural drive increases following resistance training in patients with multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 260 (7): 1822–1832. doi:10.1007/s00415-013-6884-4. PMID 23483214. S2CID 848583.

- ^ Staron RS, Karapondo DL, Kraemer WJ, et al. (March 1994). "Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women". Journal of Applied Physiology. 76 (3): 1247–1255. doi:10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1247. PMID 8005869. S2CID 24328546.

- ^ Folland JP, Williams AG (2007). "The adaptations to strength training: morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength". Sports Medicine. 37 (2): 145–168. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737020-00004. PMID 17241104. S2CID 9070800.

- ^ Moritani T, deVries HA (June 1979). "Neural factors versus hypertrophy in the time course of muscle strength gain". American Journal of Physical Medicine. 58 (3): 115–130. PMID 453338.

- ^ Narici MV, Roi GS, Landoni L, Minetti AE, Cerretelli P (1989). "Changes in force, cross-sectional area and neural activation during strength training and detraining of the human quadriceps". European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 59 (4): 310–319. doi:10.1007/bf02388334. PMID 2583179. S2CID 2231992.

- ^ Pedersen BK (July 2013). "Muscle as a secretory organ". Comprehensive Physiology. 3 (3): 1337–1362. doi:10.1002/cphy.c120033. ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4. PMID 23897689.

- ^ Cohen S, Williamson GM (January 1991). "Stress and infectious disease in humans". Psychological Bulletin. 109 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.5. PMID 2006229.

- ^ Borer KT, Wuorinen EC, Lukos JR, Denver JW, Porges SW, Burant CF (August 2009). "Two bouts of exercise before meals, but not after meals, lower fasting blood glucose". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 41 (8): 1606–1614. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819dfe14. PMID 19568199. S2CID 207184758.

- ^ Wisløff U, Ellingsen Ø, Kemi OJ (July 2009). "High-intensity interval training to maximize cardiac benefits of exercise training?". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 37 (3): 139–146. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181aa65fc. PMID 19550205. S2CID 25057561.

- ^ Paillard T, Rolland Y, de Souto Barreto P (July 2015). "Protective Effects of Physical Exercise in Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: A Narrative Review". Journal of Clinical Neurology. 11 (3): 212–219. doi:10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.212. PMC 4507374. PMID 26174783.

- ^ Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW (January 2015). "A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 60: 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. PMC 4314337. PMID 25455510.

- ^ Tarumi T, Zhang R (January 2014). "Cerebral hemodynamics of the aging brain: risk of Alzheimer disease and benefit of aerobic exercise". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 6. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00006. PMC 3896879. PMID 24478719.

- ^ Howe TE, Rochester L, Neil F, Skelton DA, Ballinger C (November 2011). "Exercise for improving balance in older people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (11) CD004963. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004963.pub3. PMC 11493176. PMID 22071817. S2CID 205176433.

- ^ Liu CJ, Latham NK (July 2009). "Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (3) CD002759. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002759.pub2. PMC 4324332. PMID 19588334.

- ^ Gc V, Wilson EC, Suhrcke M, Hardeman W, Sutton S (April 2016). "Are brief interventions to increase physical activity cost-effective? A systematic review". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50 (7): 408–417. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094655. PMC 4819643. PMID 26438429.

- ^ Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, et al. (May 2002). "The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 22 (4 Suppl): 73–107. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00434-8. PMID 11985936.

- ^ Durán VH. "Stopping the rising tide of chronic diseases Everyone's Epidemic". Pan American Health Organization. paho.org. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Xu H, Wen LM, Rissel C (19 March 2015). "Associations of parental influences with physical activity and screen time among young children: a systematic review". Journal of Obesity. 2015 546925. doi:10.1155/2015/546925. PMC 4383435. PMID 25874123.

- ^ "Youth Physical Activity Guidelines". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 January 2019.

- ^ "Health and Participation". European Commission. 25 June 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019.

- ^ a b "WHO: Obesity and overweight". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Kennedy AB, Resnick PB (May 2015). "Mindfulness and Physical Activity". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 9 (3): 3221–3323. doi:10.1177/1559827614564546. S2CID 73116017.

- ^ "Running and jogging - health benefits". Better Health. State of Victoria, Australia.

- ^ "5 Reasons Why Skateboarding Is Good Exercise". Longboarding Nation. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Swimming - health benefits". Better Health. State of Victoria, Australia.

- ^ Hernández J (24 June 2008). "Car-Free Streets, a Colombian Export, Inspire Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Sullivan N. "Gyms". Travel Fish. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Tatlow A. "When in Sweden...making the most of the great outdoors!". Stockholm on a Shoestring. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Langfitt F. "Beijing's Other Games: Dancing In The Park". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ MacDonald, Christopher; Bennekou, Mia; Midtgaard, Julie; Langberg, Hennig; Lieberman, Daniel (27 November 2024). "Why exercise may never be effective medicine: an evolutionary perspective on the efficacy versus effectiveness of exercise in treating type 2 diabetes". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 59 (2): bjsports–2024–108396. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2024-108396. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 39603793.

- ^ Collado-Mateo, Daniel; Lavín-Pérez, Ana Myriam; Peñacoba, Cecilia; Del Coso, Juan; Leyton-Román, Marta; Luque-Casado, Antonio; Gasque, Pablo; Fernández-Del-Olmo, Miguel Ángel; Amado-Alonso, Diana (19 February 2021). "Key Factors Associated with Adherence to Physical Exercise in Patients with Chronic Diseases and Older Adults: An Umbrella Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (4): 2023. doi:10.3390/ijerph18042023. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 7922504. PMID 33669679.

- ^ Kimber NE, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL, Dyck DJ (May 2003). "Skeletal muscle fat and carbohydrate metabolism during recovery from glycogen-depleting exercise in humans". The Journal of Physiology. 548 (Pt 3): 919–927. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031179. PMC 2342904. PMID 12651914.

- ^ Reilly T, Ekblom B (June 2005). "The use of recovery methods post-exercise". Journal of Sports Sciences. 23 (6): 619–627. doi:10.1080/02640410400021302. PMID 16195010. S2CID 27918213.

- ^ Bonilla, Diego A.; Pérez-Idárraga, Alexandra; Odriozola-Martínez, Adrián; Kreider, Richard B. (2021). "The 4R's framework of nutritional strategies for post-exercise Recovery: A review with emphasis on new generation of carbohydrates". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (1): 103. doi:10.3390/ijerph18010103. PMC 7796021. PMID 33375691.

- ^ Blundell JE, Gibbons C, Caudwell P, Finlayson G, Hopkins M (February 2015). "Appetite control and energy balance: impact of exercise" (PDF). Obesity Reviews. 16 (Suppl 1): 67–76. doi:10.1111/obr.12257. PMID 25614205. S2CID 39429480.

- ^ Walker, Brad (17 March 2002). "Overtraining – Learn how to identify Overtraining Syndrome". stretchcoach.com. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Stone, M (1991). "Overtraining: A Review of the Signs, Symptoms and Possible Causes". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 5: 35–50. doi:10.1519/00124278-199102000-00006.

- ^ Peluso M., Andrade L. (2005). "Physical activity and mental health: the association between exercise and mood". Clinics. 60 (1): 61–70. doi:10.1590/s1807-59322005000100012. PMID 15838583.

- ^ Carfagno D.; Hendrix J. (2014). "Overtraining Syndrome in the Athlete". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 13 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1249/jsr.0000000000000027. PMID 24412891. S2CID 38361107.

- ^ Whyte, Gregory; Harries, Mark; Williams, Clyde (2005). ABC of sports and exercise medicine. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-0-7279-1813-0.

- ^ "Quotes About Exercise Top 10 List".

- ^ "History of Fitness". unm.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "Physical culture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Bogdanovic N (2017). Fit to Fight: A History of the Royal Army Physical Training Corps 1860–2015. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4728-2421-9.

- ^ Campbell JD (2016). 'The Army Isn't All Work': Physical Culture and the Evolution of the British Army, 1860–1920. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-04453-6.

- ^ Mason T, Riedi E (2010). Sport and the Military: The British Armed Forces 1880–1960. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-78897-7.

- ^ "The Fitness League History". The Fitness League. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Kuper S (11 September 2009). "The man who invented exercise". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ a b Morris JN, Heady JA, Raffle PA, Roberts CG, Parks JW (November 1953). "Coronary heart-disease and physical activity of work". Lancet. 262 (6795): 1053–1057. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(53)90665-5. PMID 13110049.

- ^ Herman Pontzer (1 January 2019). "Humans Evolved to Exercise: Unlike our ape cousins, humans require high levels of physical activity to be healthy". Scientific American.

- ^ Zhu S, Eclarinal J, Baker MS, Li G, Waterland RA (February 2016). "Developmental programming of energy balance regulation: is physical activity more 'programmable' than food intake?". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 75 (1): 73–77. doi:10.1017/s0029665115004127. PMID 26511431.

- ^ Acosta W, Meek TH, Schutz H, Dlugosz EM, Vu KT, Garland T (October 2015). "Effects of early-onset voluntary exercise on adult physical activity and associated phenotypes in mice". Physiology & Behavior. 149: 279–286. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.06.020. PMID 26079567.

- ^ Swallow JG, Carter PA, Garland T (May 1998). "Artificial selection for increased wheel-running behavior in house mice". Behavior Genetics. 28 (3): 227–237. doi:10.1023/A:1021479331779. PMID 9670598. S2CID 18336243.

- ^ Swallow JG, Garland T, Carter PA, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC (January 1998). "Effects of voluntary activity and genetic selection on aerobic capacity in house mice (Mus domesticus)". Journal of Applied Physiology. 84 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.69. PMID 9451619.

- ^ Rhodes JS, van Praag H, Jeffrey S, Girard I, Mitchell GS, Garland T, Gage FH (October 2003). "Exercise increases hippocampal neurogenesis to high levels but does not improve spatial learning in mice bred for increased voluntary wheel running". Behavioral Neuroscience. 117 (5): 1006–1016. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.117.5.1006. PMID 14570550.

- ^ Garland T, Morgan MT, Swallow JG, Rhodes JS, Girard I, Belter JG, Carter PA (June 2002). "Evolution of a small-muscle polymorphism in lines of house mice selected for high activity levels". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 56 (6): 1267–1275. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[1267:EOASMP]2.0.CO;2. PMID 12144025. S2CID 198158847.

- ^ Gallaugher PE, Thorarensen H, Kiessling A, Farrell AP (August 2001). "Effects of high intensity exercise training on cardiovascular function, oxygen uptake, internal oxygen transport and osmotic balance in chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) during critical speed swimming". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (Pt 16): 2861–2872. Bibcode:2001JExpB.204.2861G. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.16.2861. PMID 11683441.

- ^ Palstra AP, Mes D, Kusters K, Roques JA, Flik G, Kloet K, Blonk RJ (2015). "Forced sustained swimming exercise at optimal speed enhances growth of juvenile yellowtail kingfish (Seriola lalandi)". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 506. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00506. PMC 4287099. PMID 25620933.

- ^ Magnoni LJ, Crespo D, Ibarz A, Blasco J, Fernández-Borràs J, Planas JV (November 2013). "Effects of sustained swimming on the red and white muscle transcriptome of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed a carbohydrate-rich diet". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 166 (3): 510–521. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.08.005. hdl:11336/24277. PMID 23968867.

- ^ a b Owerkowicz T, Baudinette RV (June 2008). "Exercise training enhances aerobic capacity in juvenile estuarine crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 150 (2): 211–216. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.04.594. PMID 18504156.

- ^ Eme J, Owerkowicz T, Gwalthney J, Blank JM, Rourke BC, Hicks JW (November 2009). "Exhaustive exercise training enhances aerobic capacity in American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)". Journal of Comparative Physiology B: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 179 (8) 921: 921–931. doi:10.1007/s00360-009-0374-0. PMC 2768110. PMID 19533151.

- ^ Butler PJ, Turner DL (July 1988). "Effect of training on maximal oxygen uptake and aerobic capacity of locomotory muscles in tufted ducks, Aythya fuligula". The Journal of Physiology. 401: 347–359. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017166. PMC 1191853. PMID 3171990.

- ^ a b Garland T, Else PL, Hulbert AJ, Tap P (March 1987). "Effects of endurance training and captivity on activity metabolism of lizards". The American Journal of Physiology. 252 (3 Pt 2): R450 – R456. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.3.R450. PMID 3826409. S2CID 8771310.

- ^ a b Husak JF, Keith AR, Wittry BN (March 2015). "Making Olympic lizards: the effects of specialised exercise training on performance". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (Pt 6): 899–906. Bibcode:2015JExpB.218..899H. doi:10.1242/jeb.114975. PMID 25617462.

External links

[edit]- Adult Compendium of Physical Activities – a website containing lists of Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) values for a number of physical activities, based upon PMID 8292105, 10993420 and 21681120

- MedLinePlus Topic on Exercise and Physical Fitness

- Physical activity and the environment – guidance on the promotion and creation of physical environments that support increased levels of physical activity.

- Science Daily's reference on physical exercise

.jpg/250px-Cycling_in_Amsterdam_(893).jpg)

.jpg/1774px-Cycling_in_Amsterdam_(893).jpg)

![Running helps in achieving physical fitness.[129]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9a/Woman_running_barefoot_on_beach.jpg/120px-Woman_running_barefoot_on_beach.jpg)

![Skateboarding is good for cardiovascular health[better source needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Cruising_on_a_Board.jpg/250px-Cruising_on_a_Board.jpg)

![Swimming as an exercise tones muscles and builds strength.[131]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/10/IDHM_Wasserspringen_2018-02-18_3m_mixed_Vorkampf_Sprung_3_18.jpg/120px-IDHM_Wasserspringen_2018-02-18_3m_mixed_Vorkampf_Sprung_3_18.jpg)