Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Paracrine signaling

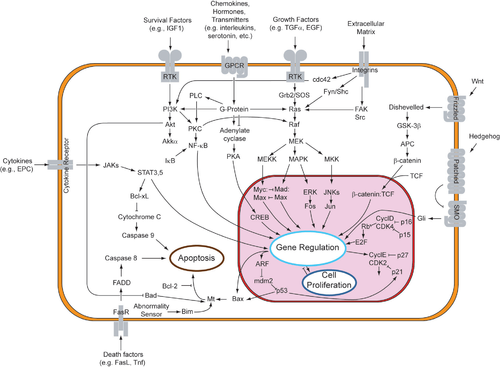

View on WikipediaIn cellular biology, paracrine signaling is a form of cell signaling, a type of cellular communication in which a cell produces a signal to induce changes in nearby cells, altering the behaviour of those cells. Signaling molecules known as paracrine factors diffuse over a relatively short distance (local action), as opposed to cell signaling by endocrine factors, hormones which travel considerably longer distances via the circulatory system; juxtacrine interactions; and autocrine signaling. Cells that produce paracrine factors secrete them into the immediate extracellular environment. Factors then travel to nearby cells in which the gradient of factor received determines the outcome. However, the exact distance that paracrine factors can travel is not certain.

Although paracrine signaling elicits a diverse array of responses in the induced cells, most paracrine factors utilize a relatively streamlined set of receptors and pathways. In fact, different organs in the body - even between different species - are known to utilize a similar sets of paracrine factors in differential development.[1] The highly conserved receptors and pathways can be organized into four major families based on similar structures: fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, Hedgehog family, Wnt family, and TGF-β superfamily. Binding of a paracrine factor to its respective receptor initiates signal transduction cascades, eliciting different responses.

Paracrine factors induce competent responders

[edit]In order for paracrine factors to successfully induce a response in the receiving cell, that cell must have the appropriate receptors available on the cell membrane to receive the signals, also known as being competent. Additionally, the responding cell must also have the ability to be mechanistically induced.[citation needed]

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family

[edit]Although the FGF family of paracrine factors has a broad range of functions, major findings support the idea that they primarily stimulate proliferation and differentiation.[2][3] To fulfill many diverse functions, FGFs can be alternatively spliced or even have different initiation codons to create hundreds of different FGF isoforms.[4]

One of the most important functions of the FGF receptors (FGFR) is in limb development. This signaling involves nine different alternatively spliced isoforms of the receptor.[5] Fgf8 and Fgf10 are two of the critical players in limb development. In the forelimb initiation and limb growth in mice, axial (lengthwise) cues from the intermediate mesoderm produces Tbx5, which subsequently signals to the same mesoderm to produce Fgf10. Fgf10 then signals to the ectoderm to begin production of Fgf8, which also stimulates the production of Fgf10. Deletion of Fgf10 results in limbless mice.[6]

Additionally, paracrine signaling of Fgf is essential in the developing eye of chicks. The fgf8 mRNA becomes localized in what differentiates into the neural retina of the optic cup. These cells are in contact with the outer ectoderm cells, which will eventually become the lens.[4]

Phenotype and survival of mice after knockout of some FGFR genes:[5]

| FGFR Knockout Gene | Survival | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Fgf1 | Viable | Unclear |

| Fgf3 | Viable | Inner ear, skeletal (tail) differentiation |

| Fgf4 | Lethal | Inner cell mass proliferation |

| Fgf8 | Lethal | Gastrulation defect, CNS development, limb development |

| Fgf10 | Lethal | Development of multiple organs (including limbs, thymus, pituitary) |

| Fgf17 | Viable | Cerebellar Development |

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) pathway

[edit]Paracrine signaling through fibroblast growth factors and its respective receptors utilizes the receptor tyrosine pathway. This signaling pathway has been highly studied, using Drosophila eyes and human cancers.[7]

Binding of FGF to FGFR phosphorylates the idle kinase and activates the RTK pathway. This pathway begins at the cell membrane surface, where a ligand binds to its specific receptor. Ligands that bind to RTKs include fibroblast growth factors, epidermal growth factors, platelet-derived growth factors, and stem cell factor.[7] This dimerizes the transmembrane receptor to another RTK receptor, which causes the autophosphorylation and subsequent conformational change of the homodimerized receptor. This conformational change activates the dormant kinase of each RTK on the tyrosine residue. Due to the fact that the receptor spans across the membrane from the extracellular environment, through the lipid bilayer, and into the cytoplasm, the binding of the receptor to the ligand also causes the trans phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor.[8]

An adaptor protein (such as SOS) recognizes the phosphorylated tyrosine on the receptor. This protein functions as a bridge which connects the RTK to an intermediate protein (such as GNRP), starting the intracellular signaling cascade. In turn, the intermediate protein stimulates GDP-bound Ras to the activated GTP-bound Ras. GAP eventually returns Ras to its inactive state. Activation of Ras has the potential to initiate three signaling pathways downstream of Ras: Ras→Raf→MAP kinase pathway, PI3 kinase pathway, and Ral pathway. Each pathway leads to the activation of transcription factors which enter the nucleus to alter gene expression.[9]

RTK receptor and cancer

[edit]Paracrine signaling of growth factors between nearby cells has been shown to exacerbate carcinogenesis. In fact, mutant forms of a single RTK may play a causal role in very different types of cancer. The Kit proto-oncogene encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor whose ligand is a paracrine protein called stem cell factor (SCF), which is important in hematopoiesis (formation of cells in blood).[10] The Kit receptor and related tyrosine kinase receptors actually are inhibitory and effectively suppresses receptor firing. Mutant forms of the Kit receptor, which fire constitutively in a ligand-independent fashion, are found in a diverse array of cancerous malignancies.[11]

RTK pathway and cancer

[edit]Research on thyroid cancer has elucidated the theory that paracrine signaling may aid in creating tumor microenvironments. Chemokine transcription is upregulated when Ras is in the GTP-bound state. The chemokines are then released from the cell, free to bind to another nearby cell. Paracrine signaling between neighboring cells creates this positive feedback loop. Thus, the constitutive transcription of upregulated proteins form ideal environments for tumors to arise.[citation needed] Effectively, multiple bindings of ligands to the RTK receptors overstimulates the Ras-Raf-MAPK pathway, which overexpresses the mitogenic and invasive capacity of cells.[12]

JAK-STAT pathway

[edit]In addition to RTK pathway, fibroblast growth factors can also activate the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Instead of carrying covalently associated tyrosine kinase domains, Jak-STAT receptors form noncovalent complexes with tyrosine kinases of the Jak (Janus kinase) class. These receptors bind are for erythropoietin (important for erythropoiesis), thrombopoietin (important for platelet formation), and interferon (important for mediating immune cell function).[13]

After dimerization of the cytokine receptors following ligand binding, the JAKs transphosphorylate each other. The resulting phosphotyrosines attract STAT proteins. The STAT proteins dimerize and enter the nucleus to act as transcription factors to alter gene expression.[13] In particular, the STATs transcribe genes that aid in cell proliferation and survival – such as myc.[14]

Phenotype and survival of mice after knockout of some JAK or STAT genes:[15]

| Knockout Gene | Survival | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Jak1 | Lethal | Neurologic Deficits |

| Jak2 | Lethal | Failure in erythropoiesis |

| Stat1 | Viable | Human dwarfism and craniosynostosis syndromes |

| Stat3 | Lethal | Tissue specific phenotypes |

| Stat4 | Viable | defective IL-12-driven Th1 differentiation, increased susceptibility to intracellular pathogens |

Aberrant JAK-STAT pathway and bone mutations

[edit]The JAK-STAT signaling pathway is instrumental in the development of limbs, specifically in its ability to regulate bone growth through paracrine signaling of cytokines. However, mutations in this pathway have been implicated in severe forms of dwarfism: thanatophoric dysplasia (lethal) and achondroplasic dwarfism (viable).[16] This is due to a mutation in a Fgf gene, causing a premature and constitutive activation of the Stat1 transcription factor. Chondrocyte cell division is prematurely terminated, resulting in lethal dwarfism. Rib and limb bone growth plate cells are not transcribed. Thus, the inability of the rib cage to expand prevents the newborn's breathing.[17]

JAK-STAT pathway and cancer

[edit]Research on paracrine signaling through the JAK-STAT pathway revealed its potential in activating invasive behavior of ovarian epithelial cells. This epithelial to mesenchymal transition is highly evident in metastasis.[18] Paracrine signaling through the JAK-STAT pathway is necessary in the transition from stationary epithelial cells to mobile mesenchymal cells, which are capable of invading surrounding tissue. Only the JAK-STAT pathway has been found to induce migratory cells.[19]

Hedgehog family

[edit]The Hedgehog protein family is involved in induction of cell types and the creation of tissue boundaries and patterning and are found in all bilateral organisms. Hedgehog proteins were first discovered and studied in Drosophila. Hedgehog proteins produce key signals for the establishment of limb and body plan of fruit flies as well as homeostasis of adult tissues, involved in late embryogenesis and metamorphosis. At least three "Drosophila" hedgehog homologs have been found in vertebrates: sonic hedgehog, desert hedgehog, and Indian hedgehog. Sonic hedgehog (SHH) has various roles in vertebrae development, mediating signaling and regulating the organization of central nervous system, limb, and somite polarity. Desert hedgehog (DHH) is expressed in the Sertoli cells involved in spermatogenesis. Indian hedgehog (IHH) is expressed in the gut and cartilage, important in postnatal bone growth.[20][21][22]

Hedgehog signaling pathway

[edit]

Members of the Hedgehog protein family act by binding to a transmembrane "Patched" receptor, which is bound to the "Smoothened" protein, by which the Hedgehog signal can be transduced. In the absence of Hedgehog, the Patched receptor inhibits Smoothened action. Inhibition of Smoothened causes the Cubitus interruptus (Ci), Fused, and Cos protein complex attached to microtubules to remain intact. In this conformation, the Ci protein is cleaved so that a portion of the protein is allowed to enter the nucleus and act as a transcriptional repressor. In the presence of Hedgehog, Patched no longer inhibits Smoothened. Then active Smoothened protein is able to inhibit PKA and Slimb, so that the Ci protein is not cleaved. This intact Ci protein can enter the nucleus, associate with CPB protein and act as a transcriptional activator, inducing the expression of Hedgehog-response genes.[22][23][24]

Hedgehog signaling pathway and cancer

[edit]The Hedgehog Signaling pathway is critical in proper tissue patterning and orientation during normal development of most animals. Hedgehog proteins induce cell proliferation in certain cells and differentiations in others. Aberrant activation of the Hedgehog pathway has been implicated in several types of cancers, Basal Cell Carcinoma in particular. This uncontrolled activation of the Hedgehog proteins can be caused by mutations to the signal pathway, which would be ligand independent, or a mutation that causes overexpression of the Hedgehog protein, which would be ligand dependent. In addition, therapy-induced Hedgehog pathway activation has been shown to be necessary for progression of Prostate Cancer tumors after androgen deprivation therapy.[25] This connection between the Hedgehog signaling pathway and human cancers may provide for the possible of therapeutic intervention as treatment for such cancers. The Hedgehog signaling pathway is also involved in normal regulation of stem-cell populations, and required for normal growth and regeneration of damaged organs. This may provide another possible route for tumorigenesis via the Hedgehog pathway.[26][27][28]

Wnt family

[edit]

The Wnt protein family includes a large number of cysteine-rich glycoproteins. The Wnt proteins activate signal transduction cascades via three different pathways, the canonical Wnt pathway, the noncanonical planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway, and the noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway. Wnt proteins appear to control a wide range of developmental processes and have been seen as necessary for control of spindle orientation, cell polarity, cadherin mediated adhesion, and early development of embryos in many different organisms. Current research has indicated that deregulation of Wnt signaling plays a role in tumor formation because, at a cellular level, Wnt proteins often regulated cell proliferation, cell morphology, cell motility, and cell fate.[29]

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway

[edit]

In the canonical pathway, Wnt proteins binds to its transmembrane receptor of the Frizzled family of proteins. The binding of Wnt to a Frizzled protein activates the Dishevelled protein. In its active state the Dishevelled protein inhibits the activity of the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) enzyme. Normally active GSK3 prevents the dissociation of β-catenin to the APC protein, which results in β-catenin degradation. Thus inhibited GSK3, allows β-catenin to dissociate from APC, accumulate, and travel to nucleus. In the nucleus β-catenin associates with Lef/Tcf transcription factor, which is already working on DNA as a repressor, inhibiting the transcription of the genes it binds. Binding of β-catenin to Lef/Tcf works as a transcription activator, activating the transcription of the Wnt-responsive genes.[30][31][32]

The noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways

[edit]The noncanonical Wnt pathways provide a signal transduction pathway for Wnt that does not involve β-catenin. In the noncanonical pathways, Wnt affects the actin and microtubular cytoskeleton as well as gene transcription.

The noncanonical planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway

[edit]

The noncanonical PCP pathway regulates cell morphology, division, and movement. Once again Wnt proteins binds to and activates Frizzled so that Frizzled activates a Dishevelled protein that is tethered to the plasma membrane through a Prickle protein and transmembrane Stbm protein. The active Dishevelled activates RhoA GTPase through Dishevelled associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (Daam1) and the Rac protein. Active RhoA is able to induce cytoskeleton changes by activating Roh-associated kinase (ROCK) and affect gene transcription directly. Active Rac can directly induce cytoskeleton changes and affect gene transcription through activation of JNK.[30][31][32]

The noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway

[edit]

The noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway regulates intracellular calcium levels. Again Wnt binds and activates to Frizzled. In this case however activated Frizzled causes a coupled G-protein to activate a phospholipase (PLC), which interacts with and splits PIP2 into DAG and IP3. IP3 can then bind to a receptor on the endoplasmic reticulum to release intracellular calcium stores, to induce calcium-dependent gene expression.[30][31][32]

Wnt signaling pathways and cancer

[edit]The Wnt signaling pathways are critical in cell-cell signaling during normal development and embryogenesis and required for maintenance of adult tissue, therefore it is not difficult to understand why disruption in Wnt signaling pathways can promote human degenerative disease and cancer.

The Wnt signaling pathways are complex, involving many different elements, and therefore have many targets for misregulation. Mutations that cause constitutive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway lead to tumor formation and cancer. Aberrant activation of the Wnt pathway can lead to increase cell proliferation. Current research is focused on the action of the Wnt signaling pathway the regulation of stem cell choice to proliferate and self renew. This action of Wnt signaling in the possible control and maintenance of stem cells, may provide a possible treatment in cancers exhibiting aberrant Wnt signaling.[33][34][35]

TGF-β superfamily

[edit]"TGF" (Transforming Growth Factor) is a family of proteins that includes 33 members that encode dimeric, secreted polypeptides that regulate development.[36] Many developmental processes are under its control including gastrulation, axis symmetry of the body, organ morphogenesis, and tissue homeostasis in adults.[37] All TGF-β ligands bind to either Type I or Type II receptors, to create heterotetramic complexes.[38]

TGF-β pathway

[edit]The TGF-β pathway regulates many cellular processes in developing embryo and adult organisms, including cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and homeostasis. There are five kinds of type II receptors and seven types of type I receptors in humans and other mammals. These receptors are known as "dual-specificity kinases" because their cytoplasmic kinase domain has weak tyrosine kinase activity but strong serine/threonine kinase activity.[39] When a TGF-β superfamily ligand binds to the type II receptor, it recruits a type I receptor and activates it by phosphorylating the serine or threonine residues of its "GS" box.[40] This forms an activation complex that can then phosphorylate SMAD proteins.

SMAD pathway

[edit]There are three classes of SMADs:

Examples of SMADs in each class:[41][42][43]

| Class | SMADs |

|---|---|

| R-SMAD | SMAD1, SMAD2, SMAD3, SMAD5 and SMAD8/9 |

| Co-SMAD | SMAD4 |

| I-SMAD | SMAD6 and SMAD7 |

The TGF-β superfamily activates members of the SMAD family, which function as transcription factors. Specifically, the type I receptor, activated by the type II receptor, phosphorylates R-SMADs that then bind to the co-SMAD, SMAD4. The R-SMAD/Co-SMAD forms a complex with importin and enters the nucleus, where they act as transcription factors and either up-regulate or down-regulate in the expression of a target gene.

Specific TGF-β ligands will result in the activation of either the SMAD2/3 or the SMAD1/5 R-SMADs. For instance, when activin, Nodal, or TGF-β ligand binds to the receptors, the phosphorylated receptor complex can activate SMAD2 and SMAD3 through phosphorylation. However, when a BMP ligand binds to the receptors, the phosphorylated receptor complex activates SMAD1 and SMAD5. Then, the Smad2/3 or the Smad1/5 complexes form a dimer complex with SMAD4 and become transcription factors. Though there are many R-SMADs involved in the pathway, there is only one co-SMAD, SMAD4.[44]

Non-SMAD pathway

[edit]Non-Smad signaling proteins contribute to the responses of the TGF-β pathway in three ways. First, non-Smad signaling pathways phosphorylate the Smads. Second, Smads directly signal to other pathways by communicating directly with other signaling proteins, such as kinases. Finally, the TGF-β receptors directly phosphorylate non-Smad proteins.[45]

Members of TGF-β superfamily

[edit]1. TGF-β family

[edit]This family includes TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, and TGF-β5. They are involved in positively and negatively regulation of cell division, the formation of the extracellular matrix between cells, apoptosis, and embryogenesis. They bind to TGF-β type II receptor (TGFBRII).

TGF-β1 stimulates the synthesis of collagen and fibronectin and inhibits the degradation of the extracellular matrix. Ultimately, it increases the production of extracellular matrix by epithelial cells.[38] TGF-β proteins regulate epithelia by controlling where and when they branch to form kidney, lung, and salivary gland ducts.[38]

2. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMPs) family

[edit]Members of the BMP family were originally found to induce bone formation, as their name suggests. However, BMPs are very multifunctional and can also regulate apoptosis, cell migration, cell division, and differentiation. They also specify the anterior/posterior axis, induce growth, and regulate homeostasis.[36]

The BMPs bind to the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (BMPR2). Some of the proteins of the BMP family are BMP4 and BMP7. BMP4 promotes bone formation, causes cell death, or signals the formation of epidermis, depending on the tissue it is acting on. BMP7 is crucial for kidney development, sperm synthesis, and neural tube polarization. Both BMP4 and BMP7 regulate mature ligand stability and processing, including degrading ligands in lysosomes.[36] BMPs act by diffusing from the cells that create them.[46]

Other members of TGF-β superfamily

[edit]- Vg1 Family

- Activin Family

- Involved in embryogenesis and osteogenesis

- Regulate insulin and pituitary, gonadal, and hypothalamic hormones

- Nerve cell survival factors

- 3 Activins: Activin A, Activin B and Activin AB.

- Glial-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF)

- Needed for kidney and enteric neuron differentiation

- Müllerian Inhibitory Factor

- Involved in mammalian sex determination

- Nodal

- Binds to Activin A Type 2B receptor

- Forms receptor complex with Activin A Type 1B receptor or with Activin A Type 1C receptor.[47]

- Growth and differentiation factors (GDFs)

Summary table of TGF-β signaling pathway

[edit]| TGF Beta superfamily ligand | Type II Receptor | Type I Receptor | R-SMADs | Co-SMAD | Ligand Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activin A | ACVR2A | ACVR1B (ALK4) | SMAD2, SMAD3 | SMAD4 | Follistatin |

| GDF1 | ACVR2A | ACVR1B (ALK4) | SMAD2, SMAD3 | SMAD4 | |

| GDF11 | ACVR2B | ACVR1B (ALK4), TGFβRI (ALK5) | SMAD2, SMAD3 | SMAD4 | |

| Bone morphogenetic proteins | BMPR2 | BMPR1A (ALK3), BMPR1B (ALK6) | SMAD1 SMAD5, SMAD8 | SMAD4 | Noggin, Chordin, DAN |

| Nodal | ACVR2B | ACVR1B (ALK4), ACVR1C (ALK7) | SMAD2, SMAD3 | SMAD4 | Lefty |

| TGFβs | TGFβRII | TGFβRI (ALK5) | SMAD2, SMAD3 | SMAD4 | LTBP1, THBS1, Decorin |

Examples

[edit]Growth factor and clotting factors are paracrine signaling agents. The local action of growth factor signaling plays an especially important role in the development of tissues. Also, retinoic acid, the active form of vitamin A, functions in a paracrine fashion to regulate gene expression during embryonic development in higher animals.[48] In insects, Allatostatin controls growth through paracrine action on the corpora allata.[citation needed]

In mature organisms, paracrine signaling is involved in responses to allergens, tissue repair, the formation of scar tissue, and blood clotting.[citation needed] Histamine is a paracrine that is released by immune cells in the bronchial tree. Histamine causes the smooth muscle cells of the bronchi to constrict, narrowing the airways.[49]

See also

[edit]- cAMP dependent pathway

- Crosstalk (biology)

- Lipid signaling

- Local hormone – either a paracrine hormone, or a hormone acting in both a paracrine and an endocrine fashion

- MAPK signaling pathway

- Netpath – A curated resource of signal transduction pathways in humans

- Paracrine regulator

References

[edit]- ^ "Paracrine Factors". Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Gospodarowicz, D.; Ferrara, N.; Schweigerer, L.; Neufeld, G. (1987). "Structural Characterization and Biological Functions of Fibroblast Growth Factor". Endocrine Reviews. 8 (2): 95–114. doi:10.1210/edrv-8-2-95. PMID 2440668.

- ^ Rifkin, Daniel B.; Moscatelli, David (1989). "Recent developments in the cell biology of basic fibroblast growth factor". The Journal of Cell Biology. 109 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1083/jcb.109.1.1. JSTOR 1613457. PMC 2115467. PMID 2545723.

- ^ a b Lappi, Douglas A. (1995). "Tumor targeting through fibroblast growth factor receptors". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 6 (5): 279–88. doi:10.1006/scbi.1995.0036. PMID 8562905.

- ^ a b Xu, J.; Xu, J; Colvin, JS; McEwen, DG; MacArthur, CA; Coulier, F; Gao, G; Goldfarb, M (1996). "Receptor Specificity of the Fibroblast Growth Factor Family". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (25): 15292–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.25.15292. PMID 8663044.

- ^ Logan, M. (2003). "Finger or toe: The molecular basis of limb identity". Development. 130 (26): 6401–10. doi:10.1242/dev.00956. PMID 14660539.

- ^ a b Fantl, Wendy J; Johnson, Daniel E; Williams, Lewis T (1993). "Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 62: 453–81. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002321. PMID 7688944.

- ^ Yarden, Yosef; Ullrich, Axel (1988). "Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinases". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 57: 443–78. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.002303. PMID 3052279.

- ^ Katz, Michael E; McCormick, Frank (1997). "Signal transduction from multiple Ras effectors". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 7 (1): 75–9. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(97)80112-8. PMID 9024640.

- ^ Zsebo, Krisztina M.; Williams, David A.; Geissler, Edwin N.; Broudy, Virginia C.; Martin, Francis H.; Atkins, Harry L.; Hsu, Rou-Yin; Birkett, Neal C.; Okino, Kenneth H.; Murdock, Douglas C.; Jacobsen, Frederick W.; Langley, Keith E.; Smith, Kent A.; Takeish, Takashi; Cattanach, Bruce M.; Galli, Stephen J.; Suggs, Sidney V. (1990). "Stem cell factor is encoded at the SI locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor". Cell. 63 (1): 213–24. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90302-U. PMID 1698556. S2CID 39924379.

- ^ Rönnstrand, L. (2004). "Signal transduction via the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 61 (19–20): 2535–48. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4189-6. PMC 11924424. PMID 15526160. S2CID 2602233.

- ^ Kolch, Walter (2000). "Meaningful relationships: The regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions". The Biochemical Journal. 351 (2): 289–305. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3510289. PMC 1221363. PMID 11023813.

- ^ a b Aaronson, David S.; Horvath, Curt M. (2002). "A Road Map for Those Who Don't Know JAK-STAT". Science. 296 (5573): 1653–5. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1653A. doi:10.1126/science.1071545. PMID 12040185. S2CID 20857536.

- ^ Rawlings, Jason S.; Rosler, Kristin M.; Harrison, Douglas A. (2004). "The JAK/STAT signaling pathway". Journal of Cell Science. 117 (8): 1281–3. doi:10.1242/jcs.00963. PMID 15020666.

- ^ O'Shea, John J; Gadina, Massimo; Schreiber, Robert D (2002). "Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway". Cell. 109 (2): S121–31. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00701-8. PMID 11983158.

- ^ Shiang, Rita; Thompson, Leslie M.; Zhu, Ya-Zhen; Church, Deanna M.; Fielder, Thomas J.; Bocian, Maureen; Winokur, Sara T.; Wasmuth, John J. (1994). "Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia". Cell. 78 (2): 335–42. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90302-6. PMID 7913883. S2CID 20325070.

- ^ Kalluri, Raghu; Weinberg, Robert A. (2009). "The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 119 (6): 1420–8. doi:10.1172/JCI39104. PMC 2689101. PMID 19487818.

- ^ Silver, Debra L.; Montell, Denise J. (2001). "Paracrine Signaling through the JAK/STAT Pathway Activates Invasive Behavior of Ovarian Epithelial Cells in Drosophila". Cell. 107 (7): 831–41. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00607-9. PMID 11779460.

- ^ Ingham, P. W.; McMahon, AP (2001). "Hedgehog signaling in animal development: Paradigms and principles". Genes & Development. 15 (23): 3059–87. doi:10.1101/gad.938601. PMID 11731473.

- ^ Bitgood, Mark J.; McMahon, Andrew P. (1995). "Hedgehog and Bmp Genes Are Coexpressed at Many Diverse Sites of Cell–Cell Interaction in the Mouse Embryo". Developmental Biology. 172 (1): 126–38. doi:10.1006/dbio.1995.0010. PMID 7589793.

- ^ a b Jacob, L.; Lum, L. (2007). "Hedgehog Signaling Pathway". Science's STKE. 2007 (407): cm6. doi:10.1126/stke.4072007cm6. PMID 17925577. S2CID 35653781.

- ^ Johnson, Ronald L; Scott, Matthew P (1998). "New players and puzzles in the Hedgehog signaling pathway". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 8 (4): 450–6. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80117-2. PMID 9729722.

- ^ Nybakken, K; Perrimon, N (2002). "Hedgehog signal transduction: Recent findings". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 12 (5): 503–11. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00333-7. PMID 12200154.

- ^ Lubik AA, Nouri M, Truong S, Ghaffari M, Adomat HH, Corey E, Cox ME, Li N, Guns ES, Yenki P, Pham S, Buttyan R (2016). "Paracrine Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Contributes Significantly to Acquired Steroidogenesis in the Prostate Tumor Microenvironment". International Journal of Cancer. 140 (2): 358–369. doi:10.1002/ijc.30450. PMID 27672740. S2CID 2354209.

- ^ Collins, R. T.; Cohen, SM (2005). "A Genetic Screen in Drosophila for Identifying Novel Components of the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway". Genetics. 170 (1): 173–84. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.039420. PMC 1449730. PMID 15744048.

- ^ Evangelista, M.; Tian, H.; De Sauvage, F. J. (2006). "The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway in Cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (20): 5924–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1736. PMID 17062662.

- ^ Taipale, Jussi; Beachy, Philip A. (2001). "The Hedgehog and Wnt signaling pathways in cancer". Nature. 411 (6835): 349–54. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..349T. doi:10.1038/35077219. PMID 11357142. S2CID 4414768.

- ^ Cadigan, K. M.; Nusse, R. (1997). "Wnt signaling: A common theme in animal development". Genes & Development. 11 (24): 3286–305. doi:10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. PMID 9407023.

- ^ a b c Dale, Trevor C. (1998). "Signal transduction by the Wnt family of ligands". The Biochemical Journal. 329 (Pt 2): 209–23. doi:10.1042/bj3290209. PMC 1219034. PMID 9425102.

- ^ a b c Chen, Xi; Yang, Jun; Evans, Paul M; Liu, Chunming (2008). "Wnt signaling: The good and the bad". Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 40 (7): 577–94. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00440.x. PMC 2532600. PMID 18604449.

- ^ a b c Komiya, Yuko; Habas, Raymond (2008). "Wnt signal transduction pathways". Organogenesis. 4 (2): 68–75. doi:10.4161/org.4.2.5851. PMC 2634250. PMID 19279717.

- ^ Logan, Catriona Y.; Nusse, Roel (2004). "The Wnt Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 20: 781–810. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.322.311. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. PMID 15473860.

- ^ Lustig, B; Behrens, J (2003). "The Wnt signaling pathway and its role in tumor development". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 129 (4): 199–221. doi:10.1007/s00432-003-0431-0. PMC 12161963. PMID 12707770. S2CID 28959851.

- ^ Neth, Peter; Ries, Christian; Karow, Marisa; Egea, Virginia; Ilmer, Matthias; Jochum, Marianne (2007). "The Wnt Signal Transduction Pathway in Stem Cells and Cancer Cells: Influence on Cellular Invasion". Stem Cell Reviews. 3 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1007/s12015-007-0001-y. PMID 17873378. S2CID 25793825.

- ^ a b c Bandyopadhyay, Amitabha; Tsuji, Kunikazu; Cox, Karen; Harfe, Brian D.; Rosen, Vicki; Tabin, Clifford J. (2006). "Genetic Analysis of the Roles of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 in Limb Patterning and Skeletogenesis". PLOS Genetics. 2 (12): e216. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020216. PMC 1713256. PMID 17194222.

- ^ Attisano, Liliana; Wrana, Jeffrey L. (2002). "Signal Transduction by the TGF-β Superfamily". Science. 296 (5573): 1646–7. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1646A. doi:10.1126/science.1071809. PMID 12040180. S2CID 84138159.

- ^ a b c Wrana, Jeffrey L.; Ozdamar, Barish; Le Roy, Christine; Benchabane, Hassina (2008). "Signaling Receptors of the TGF-β Family". In Derynck, Rik; Miyazono, Kohei (eds.). The TGF-β Family. CSHL Press. pp. 151–77. ISBN 978-0-87969-752-5.

- ^ ten Dijke, Peter; Heldin, Carl-Henrik (2006). "The Smad family". In ten Dijke, Peter; Heldin, Carl-Henrik (eds.). Smad Signal Transduction: Smads in Proliferation, Differentiation and Disease. Proteins and Cell Regulation. Vol. 5. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-1-4020-4709-1.

- ^ Moustakas, Aristidis (2002-09-01). "Smad signaling network". Journal of Cell Science. 115 (17): 3355–6. doi:10.1242/jcs.115.17.3355. PMID 12154066.

- ^ Wu, Jia-Wei; Hu, Min; Chai, Jijie; Seoane, Joan; Huse, Morgan; Li, Carey; Rigotti, Daniel J.; Kyin, Saw; Muir, Tom W.; Fairman, Robert; Massagué, Joan; Shi, Yigong (2001). "Crystal Structure of a Phosphorylated Smad2". Molecular Cell. 8 (6): 1277–89. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00421-X. PMID 11779503.

- ^ Pavletich, Nikola P.; Hata, Yigong; Lo, Akiko; Massagué, Roger S.; Pavletich, Joan (1997). "A structural basis for mutational inactivation of the tumour suppressor Smad4". Nature. 388 (6637): 87–93. Bibcode:1997Natur.388R..87S. doi:10.1038/40431. PMID 9214508.

- ^ Itoh, Fumiko; Asao, Hironobu; Sugamura, Kazuo; Heldin, Carl-Henrik; Ten Dijke, Peter; Itoh, Susumu (2001). "Promoting bone morphogenetic protein signaling through negative regulation of inhibitory Smads". The EMBO Journal. 20 (15): 4132–42. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.15.4132. PMC 149146. PMID 11483516.

- ^ Schmierer, Bernhard; Hill, Caroline S. (2007). "TGFβ–SMAD signal transduction: Molecular specificity and functional flexibility". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (12): 970–82. doi:10.1038/nrm2297. PMID 18000526. S2CID 131895.

- ^ Moustakas, Aristidis; Heldin, Carl-Henrik (2005). "Non-Smad TGF-β signals". Journal of Cell Science. 118 (16): 3573–84. doi:10.1242/jcs.02554. PMID 16105881.

- ^ Ohkawara, Bisei; Iemura, Shun-Ichiro; Ten Dijke, Peter; Ueno, Naoto (2002). "Action Range of BMP is Defined by Its N-Terminal Basic Amino Acid Core". Current Biology. 12 (3): 205–9. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00684-4. PMID 11839272.

- ^ Munir, Sadia; Xu, Guoxiong; Wu, Yaojiong; Yang, Burton; Lala, Peeyush K.; Peng, Chun (2004). "Nodal and ALK7 Inhibit Proliferation and Induce Apoptosis in Human Trophoblast Cells". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (30): 31277–86. doi:10.1074/jbc.M400641200. PMID 15150278.

- ^ Duester, Gregg (September 2008). "Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis". Cell. 134 (6): 921–31. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. PMC 2632951. PMID 18805086.

- ^

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (July 24, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 17.1 Overview of the endocrine system. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (July 24, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 17.1 Overview of the endocrine system. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

External links

[edit]- Paracrine+Signaling at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "paracrine" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary