Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neural crest

View on Wikipedia| Neural crest | |

|---|---|

The formation of neural crest during the process of neurulation. Neural crest is first induced in the region of the neural plate border. After neural tube closure, neural crest cells delaminate from the region between the dorsal neural tube and overlying ectoderm and migrate out towards the periphery. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009432 |

| TE | crest_by_E5.0.2.1.0.0.2 E5.0.2.1.0.0.2 |

| FMA | 86666 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The neural crest is a ridge-like structure that is formed transiently between the epidermal ectoderm and neural plate during vertebrate development. Neural crest cells originate from this structure through the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and in turn give rise to a diverse cell lineage—including melanocytes, craniofacial cartilage and bone, smooth muscle, dentin, peripheral and enteric neurons, adrenal medulla and glia.[1][2]

After gastrulation, the neural crest is specified at the border of the neural plate and the non-neural ectoderm. During neurulation, the borders of the neural plate, also known as the neural folds, converge at the dorsal midline to form the neural tube.[3] Subsequently, neural crest cells from the roof plate of the neural tube undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition, delaminating from the neuroepithelium and migrating through the periphery, where they differentiate into varied cell types.[1] The emergence of the neural crest was important in vertebrate evolution because many of its structural derivatives are defining features of the vertebrate clade.[4]

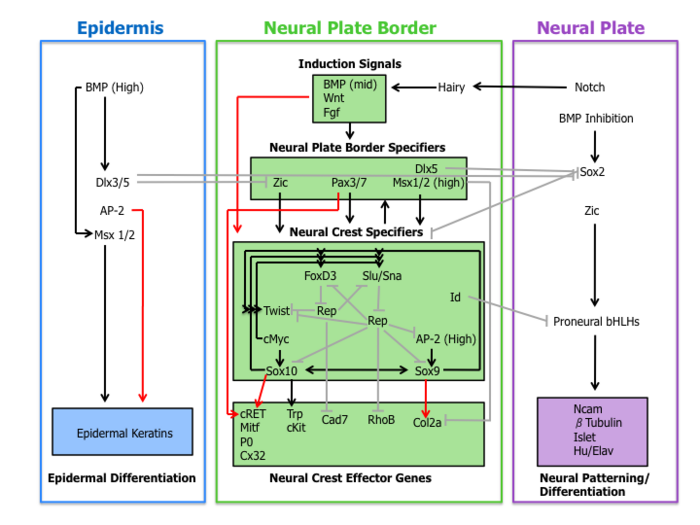

Underlying the development of the neural crest is a gene regulatory network, described as a set of interacting signals, transcription factors, and downstream effector genes, that confer cell characteristics such as multipotency and migratory capabilities.[5] Understanding the molecular mechanisms of neural crest formation is important for our knowledge of human disease because of its contributions to multiple cell lineages. Abnormalities in neural crest development cause neurocristopathies, which include conditions such as frontonasal dysplasia, Waardenburg–Shah syndrome, and DiGeorge syndrome.[1]

Defining the mechanisms of neural crest development may reveal key insights into vertebrate evolution and neurocristopathies.

History

[edit]The neural crest was first described in the chick embryo by Wilhelm His Sr. in 1868 as "the cord in between" (Zwischenstrang) because of its origin between the neural plate and non-neural ectoderm.[1] He named the tissue "ganglionic crest," since its final destination was each lateral side of the neural tube, where it differentiated into spinal ganglia.[6] During the first half of the 20th century, the majority of research on the neural crest was done using amphibian embryos which was reviewed by Hörstadius (1950) in a well known monograph.[7]

Cell labeling techniques advanced research into the neural crest because they allowed researchers to visualize the migration of the tissue throughout the developing embryos. In the 1960s, Weston and Chibon utilized radioisotopic labeling of the nucleus with tritiated thymidine in chick and amphibian embryo respectively. However, this method suffers from drawbacks of stability, since every time the labeled cell divides the signal is diluted. Modern cell labeling techniques such as rhodamine-lysinated dextran and the vital dye diI have also been developed to transiently mark neural crest lineages.[6]

The quail-chick marking system, devised by Nicole Le Douarin in 1969, was another instrumental technique used to track neural crest cells.[8][9] Chimeras, generated through transplantation, enabled researchers to distinguish neural crest cells of one species from the surrounding tissue of another species. With this technique, generations of scientists were able to reliably mark and study the ontogeny of neural crest cells.

Induction

[edit]A molecular cascade of events is involved in establishing the migratory and multipotent characteristics of neural crest cells. This gene regulatory network can be subdivided into the following four sub-networks described below.

Inductive signals

[edit]First, extracellular signaling molecules, secreted from the adjacent epidermis and underlying mesoderm such as Wnts, BMPs and Fgfs separate the non-neural ectoderm (epidermis) from the neural plate during neural induction.[1][4]

Wnt signaling has been demonstrated in neural crest induction in several species through gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments. In coherence with this observation, the promoter region of slug (a neural-crest-specific gene) contains a binding site for transcription factors involved in the activation of Wnt-dependent target genes, suggestive of a direct role of Wnt signaling in neural crest specification.[10]

The current role of BMP in neural crest formation is associated with the induction of the neural plate. BMP antagonists diffusing from the ectoderm generates a gradient of BMP activity. In this manner, the neural crest lineage forms from intermediate levels of BMP signaling required for the development of the neural plate (low BMP) and epidermis (high BMP).[1]

Fgf from the paraxial mesoderm has been suggested as a source of neural crest inductive signal. Researchers have demonstrated that the expression of dominate-negative Fgf receptor in ectoderm explants blocks neural crest induction when recombined with paraxial mesoderm.[11] The understanding of the role of BMP, Wnt, and Fgf pathways on neural crest specifier expression remains incomplete.

Neural plate border specifiers

[edit]Signaling events that establish the neural plate border lead to the expression of a set of transcription factors delineated here as neural plate border specifiers. These molecules include Zic factors, Pax3/7, Dlx5, Msx1/2 which may mediate the influence of Wnts, BMPs, and Fgfs. These genes are expressed broadly at the neural plate border region and precede the expression of bona fide neural crest markers.[4]

Experimental evidence places these transcription factors upstream of neural crest specifiers. For example, in Xenopus Msx1 is necessary and sufficient for the expression of Slug, Snail, and FoxD3.[12] Furthermore, Pax3 is essential for FoxD3 expression in mouse embryos.[13]

Neural crest specifiers

[edit]Following the expression of neural plate border specifiers is a collection of genes including Slug/Snail, FoxD3, Sox10, Sox9, AP-2 and c-Myc. This suite of genes, designated here as neural crest specifiers, are activated in emergent neural crest cells. At least in Xenopus, every neural crest specifier is necessary and/or sufficient for the expression of all other specifiers, demonstrating the existence of extensive cross-regulation.[4] Moreover, this model organism was instrumental in the elucidation of the role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in the specification of the neural crest, with the transcription factor Gli2 playing a key role.[14]

Outside of the tightly regulated network of neural crest specifiers are two other transcription factors Twist and Id. Twist, a bHLH transcription factor, is required for mesenchyme differentiation of the pharyngeal arch structures.[15] Id is a direct target of c-Myc and is known to be important for the maintenance of neural crest stem cells.[16]

Neural crest effector genes

[edit]Finally, neural crest specifiers turn on the expression of effector genes, which confer certain properties such as migration and multipotency. Two neural crest effectors, Rho GTPases and cadherins, function in delamination by regulating cell morphology and adhesive properties. Sox9 and Sox10 regulate neural crest differentiation by activating many cell-type-specific effectors including Mitf, P0, Cx32, Trp and cKit.[4]

Migration

[edit]

The migration of neural crest cells involves a highly coordinated cascade of events that begins with closure of the dorsal neural tube.

Delamination

[edit]After fusion of the neural folds to create the neural tube, cells originally located in the neural plate border become neural crest cells.[17] For migration to begin, neural crest cells must undergo a process called delamination that involves a full or partial epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT).[18] Delamination is defined as the separation of tissue into different populations, in this case neural crest cells separating from the surrounding tissue.[19] Conversely, EMT is a series of events coordinating a change from an epithelial to mesenchymal phenotype.[18] For example, delamination in chick embryos is triggered by a BMP/Wnt cascade that induces the expression of EMT promoting transcription factors such as SNAI2 and FOXD3.[19] Although all neural crest cells undergo EMT, the timing of delamination occurs at different stages in different organisms: in Xenopus laevis embryos there is a massive delamination that occurs when the neural plate is not entirely fused, whereas delamination in the chick embryo occurs during fusion of the neural fold.[19]

Prior to delamination, presumptive neural crest cells are initially anchored to neighboring cells by tight junction proteins such as occludin and cell adhesion molecules such as NCAM and N-Cadherin.[20] Dorsally expressed BMPs initiate delamination by inducing the expression of the zinc finger protein transcription factors snail, slug, and twist.[17] These factors play a direct role in inducing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition by reducing expression of occludin and N-Cadherin in addition to promoting modification of NCAMs with polysialic acid residues to decrease adhesiveness.[17][21] Neural crest cells also begin expressing proteases capable of degrading cadherins such as ADAM10[22] and secreting matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade the overlying basal lamina of the neural tube to allow neural crest cells to escape.[20] Additionally, neural crest cells begin expressing integrins that associate with extracellular matrix proteins, including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, during migration.[23] Once the basal lamina becomes permeable, neural crest cells can begin migrating throughout the embryo.

Migration

[edit]

Neural crest cell migration occurs in a rostral to caudal direction without the need of a neuronal scaffold such as along a radial glial cell. For this reason the crest cell migration process is termed "free migration". Instead of scaffolding on progenitor cells, neural crest migration is the result of repulsive guidance via EphB/EphrinB and semaphorin/neuropilin signaling, interactions with the extracellular matrix, and contact inhibition with one another.[17] While Ephrin and Eph proteins have the capacity to undergo bi-directional signaling, neural crest cell repulsion employs predominantly forward signaling to initiate a response within the receptor bearing neural crest cell.[23] Burgeoning neural crest cells express EphB, a receptor tyrosine kinase, which binds the EphrinB transmembrane ligand expressed in the caudal half of each somite. When these two domains interact it causes receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, activation of rhoGTPases, and eventual cytoskeletal rearrangements within the crest cells inducing them to repel. This phenomenon allows neural crest cells to funnel through the rostral portion of each somite.[17]

Semaphorin-neuropilin repulsive signaling works synergistically with EphB signaling to guide neural crest cells down the rostral half of somites in mice. In chick embryos, semaphorin acts in the cephalic region to guide neural crest cells through the pharyngeal arches. On top of repulsive repulsive signaling, neural crest cells express β1and α4 integrins which allows for binding and guided interaction with collagen, laminin, and fibronectin of the extracellular matrix as they travel. Additionally, crest cells have intrinsic contact inhibition with one another while freely invading tissues of different origin such as mesoderm.[17] Neural crest cells that migrate through the rostral half of somites differentiate into sensory and sympathetic neurons of the peripheral nervous system. The other main route neural crest cells take is dorsolaterally between the epidermis and the dermamyotome. Cells migrating through this path differentiate into pigment cells of the dermis. Further neural crest cell differentiation and specification into their final cell type is biased by their spatiotemporal subjection to morphogenic cues such as BMP, Wnt, FGF, Hox, and Notch.[20]

Clinical significance

[edit]Neurocristopathies result from the abnormal specification, migration, differentiation or death of neural crest cells throughout embryonic development.[24][25] This group of diseases comprises a wide spectrum of congenital malformations affecting many newborns. Additionally, they arise because of genetic defects affecting the formation of the neural crest and because of the action of teratogens [26]

Waardenburg syndrome

[edit]Waardenburg syndrome is a neurocristopathy that results from defective neural crest cell migration. The condition's main characteristics include piebaldism and congenital deafness. In the case of piebaldism, the colorless skin areas are caused by a total absence of neural crest-derived pigment-producing melanocytes.[27] There are four different types of Waardenburg syndrome, each with distinct genetic and physiological features. Types I and II are distinguished based on whether or not family members of the affected individual have dystopia canthorum.[28] Type III gives rise to upper limb abnormalities. Lastly, type IV is also known as Waardenburg-Shah syndrome, and afflicted individuals display both Waardenburg's syndrome and Hirschsprung's disease.[29] Types I and III are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion,[27] while II and IV exhibit an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Overall, Waardenburg's syndrome is rare, with an incidence of ~ 2/100,000 people in the United States. All races and sexes are equally affected.[27] There is no current cure or treatment for Waardenburg's syndrome.

Hirschsprung's disease

[edit]Also implicated in defects related to neural crest cell development and migration is Hirschsprung's disease, characterized by a lack of innervation in regions of the intestine. This lack of innervation can lead to further physiological abnormalities like an enlarged colon (megacolon), obstruction of the bowels, or even slowed growth. In healthy development, neural crest cells migrate into the gut and form the enteric ganglia. Genes playing a role in the healthy migration of these neural crest cells to the gut include RET, GDNF, GFRα, EDN3, and EDNRB. RET, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), forms a complex with GDNF and GFRα. EDN3 and EDNRB are then implicated in the same signaling network. When this signaling is disrupted in mice, aganglionosis, or the lack of these enteric ganglia occurs.[30]

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

[edit]Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is among the most common causes of developmental defects.[31] Depending on the extent of the exposure and the severity of the resulting abnormalities, patients are diagnosed within a continuum of disorders broadly labeled fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Severe FASD can impair neural crest migration, as evidenced by characteristic craniofacial abnormalities including short palpebral fissures, an elongated upper lip, and a smoothened philtrum. However, due to the promiscuous nature of ethanol binding, the mechanisms by which these abnormalities arise is still unclear. Cell culture explants of neural crest cells as well as in vivo developing zebrafish embryos exposed to ethanol show a decreased number of migratory cells and decreased distances travelled by migrating neural crest cells. The mechanisms behind these changes are not well understood, but evidence suggests PAE can increase apoptosis due to increased cytosolic calcium levels caused by IP3-mediated release of calcium from intracellular stores. It has also been proposed that the decreased viability of ethanol-exposed neural crest cells is caused by increased oxidative stress. Despite these, and other advances much remains to be discovered about how ethanol affects neural crest development. For example, it appears that ethanol differentially affects certain neural crest cells over others; that is, while craniofacial abnormalities are common in PAE, neural crest-derived pigment cells appear to be minimally affected.[32]

DiGeorge syndrome

[edit]DiGeorge syndrome is associated with deletions or translocations of a small segment in the human chromosome 22. This deletion may disrupt rostral neural crest cell migration or development. Some defects observed are linked to the pharyngeal pouch system, which receives contribution from rostral migratory crest cells. The symptoms of DiGeorge syndrome include congenital heart defects, facial defects, and some neurological and learning disabilities. Patients with 22q11 deletions have also been reported to have higher incidence of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[33]

Treacher Collins syndrome

[edit]Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS) results from the compromised development of the first and second pharyngeal arches during the early embryonic stage, which ultimately leads to mid and lower face abnormalities. TCS is caused by the missense mutation of the TCOF1 gene, which causes neural crest cells to undergo apoptosis during embryogenesis. Although mutations of the TCOF1 gene are among the best characterized in their role in TCS, mutations in POLR1C and POLR1D genes have also been linked to the pathogenesis of TCS.[34]

Cell lineages

[edit]Neural crest cells originating from different positions along the anterior-posterior axis develop into various tissues. These regions of the neural crest can be divided into four main functional domains, which include the cranial neural crest, trunk neural crest, vagal and sacral neural crest, and cardiac neural crest.

Cranial neural crest

[edit]The cranial neural crest migrates dorsolaterally to form the craniofacial mesenchyme that differentiates into various cranial ganglia and craniofacial cartilages and bones.[21] These cells enter the pharyngeal pouches and arches where they contribute to the thymus, bones of the middle ear and jaw and the odontoblasts of the tooth primordia.[35]

Trunk neural crest

[edit]The trunk neural crest gives rise to two populations of cells.[36] One group of cells fated to become melanocytes migrates dorsolaterally into the ectoderm towards the ventral midline. A second group of cells migrates ventrolaterally through the anterior portion of each sclerotome. The cells that stay in the sclerotome form the dorsal root ganglia, whereas those that continue more ventrally form the sympathetic ganglia, adrenal medulla, and the nerves surrounding the aorta.[35]

Vagal and sacral neural crest

[edit]Vagal and sacral neural crest cells develop into the ganglia of the enteric nervous system and the parasympathetic ganglia.[35]

Cardiac neural crest

[edit]Cardiac neural crest develops into melanocytes, cartilage, connective tissue and neurons of some pharyngeal arches. Also, this domain gives rise to regions of the heart such as the musculo-connective tissue of the large arteries, and part of the septum, which divides the pulmonary circulation from the aorta.[35] The semilunar valves of the heart are associated with neural crest cells according to new research.[37]

Evolution

[edit]Several structures that distinguish the vertebrates from other chordates are formed from the derivatives of neural crest cells. In their "New head" theory, Gans and Northcut argue that the presence of neural crest was the basis for vertebrate specific features, such as sensory ganglia and cranial skeleton. Furthermore, the appearance of these features was pivotal in vertebrate evolution because it enabled a predatory lifestyle.[38][39]

However, considering the neural crest a vertebrate innovation does not mean that it arose de novo. Instead, new structures often arise through modification of existing developmental regulatory programs. For example, regulatory programs may be changed by the co-option of new upstream regulators or by the employment of new downstream gene targets, thus placing existing networks in a novel context.[40][41] This idea is supported by in situ hybridization data that shows the conservation of the neural plate border specifiers in protochordates, which suggest that part of the neural crest precursor network was present in a common ancestor to the chordates.[5] In some non-vertebrate chordates such as tunicates a lineage of cells (melanocytes) has been identified, which are similar to neural crest cells in vertebrates. This implies that a rudimentary neural crest existed in a common ancestor of vertebrates and tunicates.[42]

Neural crest derivatives

[edit]Ectomesenchyme (also known as mesectoderm):[43] odontoblasts, dental papillae, the chondrocranium (nasal capsule, Meckel's cartilage, scleral ossicles, quadrate, articular, hyoid and columella), tracheal and laryngeal cartilage, the dermatocranium (membranous bones), dorsal fins and the turtle plastron (lower vertebrates), pericytes and smooth muscle of branchial arteries and veins, tendons of ocular and masticatory muscles, connective tissue of head and neck glands (pituitary, salivary, lachrymal, thymus, thyroid) dermis and adipose tissue of calvaria, ventral neck and face

Endocrine cells: chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, glomus cells type I/II.

Peripheral nervous system: Sensory neurons and glia of the dorsal root ganglia, cephalic ganglia (VII and in part, V, IX, and X), Rohon-Beard cells, some Merkel cells in the whisker,[44][45] Satellite glial cells of all autonomic and sensory ganglia, Schwann cells of all peripheral nerves.

Enteric cells: Enterochromaffin cells.[46]

Melanocytes, iris muscle and pigment cells, and even associated with some tumors (such as melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy).

See also

[edit]- First arch syndrome

- DGCR2—may control neural crest cell migration

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Huang, X.; Saint-Jeannet, J.P. (2004). "Induction of the neural crest and the opportunities of life on the edge". Dev. Biol. 275 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.033. PMID 15464568.

- ^ Shakhova, Olga; Sommer, Lukas (2008). "Neural crest-derived stem cells". StemBook. Harvard Stem Cell Institute. doi:10.3824/stembook.1.51.1. PMID 20614636. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Brooker, R.J. 2014, Biology, 3rd edn, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 1084

- ^ a b c d e Meulemans, D.; Bronner-Fraser, M. (2004). "Gene-regulatory interactions in neural crest evolution and development". Dev Cell. 7 (3): 291–9. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.007. PMID 15363405.

- ^ a b Sauka-Spengler, T.; Meulemans, D.; Jones, M.; Bronner-Fraser, M. (2007). "Ancient evolutionary origin of the neural crest gene regulatory network". Dev Cell. 13 (3): 405–20. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.005. PMID 17765683.

- ^ a b Le Douarin, N.M. (2004). "The avian embryo as a model to study the development of the neural crest: a long and still ongoing story". Mech. Dev. 121 (9): 1089–102. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2004.06.003. PMID 15296974.

- ^ Hörstadius, S. (1950). The Neural Crest: Its Properties and Derivatives in the Light of Experimental Research. Oxford University Press, London, 111 p.

- ^ Le Douarin, N.M. (1969). "Particularités du noyau interphasique chez la Caille japonaise (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Utilisation de ces particularités comme "marquage biologique" dans les recherches sur les interactions tissulaires et les migrations cellulaires au cours de l'ontogenèse"". Bull Biol Fr Belg. 103 (3): 435–52. PMID 4191116.

- ^ Le Douarin, N.M. (1973). "A biological cell labeling technique and its use in experimental embryology". Dev Biol. 30 (1): 217–22. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(73)90061-4. PMID 4121410.

- ^ Vallin, J.; et al. (2001). "Cloning and characterization of the three Xenopus slug promoters reveal direct regulation by Lef/beta-catenin signaling". J Biol Chem. 276 (32): 30350–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103167200. hdl:11365/38087. PMID 11402039.

- ^ Mayor, R.; Guerrero, N.; Martinez, C. (1997). "Role of FGF and noggin in neural crest induction". Dev Biol. 189 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8634. PMID 9281332.

- ^ Tribulo, C.; et al. (2003). "Regulation of Msx genes by Bmp gradient is essential for neural crest specification". Development. 130 (26): 6441–52. doi:10.1242/dev.00878. hdl:11336/95313. PMID 14627721.

- ^ Dottori, M.; Gross, M.K.; Labosky, P.; Goulding, M. (2001). "The winged-helix transcription factor Foxd3 suppresses interneuron differentiation and promotes neural crest cell fate". Development. 128 (21): 4127–4138. doi:10.1242/dev.128.21.4127. PMID 11684651.

- ^ Cerrizuela, Santiago; Vega-López, Guillermo A.; Palacio, María Belén; Tríbulo, Celeste; Aybar, Manuel J. (2018-12-01). "Gli2 is required for the induction and migration of Xenopus laevis neural crest". Mechanisms of Development. 154: 219–239. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2018.07.010. hdl:11336/101714. ISSN 0925-4773. PMID 30086335.

- ^ Vincentz, J.W.; et al. (2008). "An absence of Twist1 results in aberrant cardiac neural crest morphogenesis". Dev Biol. 320 (1): 131–9. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.037. PMC 2572997. PMID 18539270.

- ^ Light, W.; et al. (2005). "Xenopus Id3 is required downstream of Myc for the formation of multipotent neural crest progenitor cells". Development. 132 (8): 1831–41. doi:10.1242/dev.01734. PMID 15772131.

- ^ a b c d e f Sanes, Dan (2012). Development of the Nervous System, 3rd ed. Oxford: ELSEVIER INC. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-0123745392.

- ^ a b Lamouille, Samy (2014). "Molecular mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 15 (3): 178–196. doi:10.1038/nrm3758. PMC 4240281. PMID 24556840.

- ^ a b c Theveneau, Eric (2012). "Neural crest delamination and migration: From epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition to collective cell migration" (PDF). Developmental Biology. 366 (1): 34–54. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.041. PMID 22261150.

- ^ a b c Kandel, Eric (2013). Principles of Neural Science. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 1197–1199. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ a b Taneyhill, L.A. (2008). "To adhere or not to adhere: the role of Cadherins in neural crest development". Cell Adh Migr. 2, 223–30.

- ^ Mayor, Roberto (2013). "The Neural Crest". Development. 140 (11): 2247–2251. doi:10.1242/dev.091751. PMID 23674598.

- ^ a b Sakuka-Spengler, Tatjana (2008). "A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 9 (7): 557–568. doi:10.1038/nrm2428. PMID 18523435. S2CID 10746234.

- ^ Vega-Lopez, Guillermo A.; Cerrizuela, Santiago; Tribulo, Celeste; Aybar, Manuel J. (2018-12-01). "Neurocristopathies: New insights 150 years after the neural crest discovery". Developmental Biology. The Neural Crest: 150 years after His' discovery. 444: S110 – S143. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.05.013. hdl:11336/101713. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 29802835.

- ^ Bolande, Robert P. (1974-07-01). "The neurocristopathies: A unifying concept of disease arising in neural crest maldevelopment". Human Pathology. 5 (4): 409–429. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(74)80021-3. ISSN 0046-8177.

- ^ Cerrizuela, Santiago; Vega-Lopez, Guillermo A.; Aybar, Manuel J. (2020-01-11). "The role of teratogens in neural crest development". Birth Defects Research. 112 (8): 584–632. doi:10.1002/bdr2.1644. ISSN 2472-1727. PMID 31926062. S2CID 210151171.

- ^ a b c Mallory, S.B.; Wiener, E; Nordlund, J.J. (1986). "Waardenburg's Syndrome with Hirschprung's Disease: A Neural Crest Defect". Pediatric Dermatology. 3 (2): 119–124. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00501.x. PMID 3952027. S2CID 23858201.

- ^ Arias, S (1971). "Genetic heterogeneity in the Waardenburg's syndrome". Birth Defects B. 07 (4): 87–101. PMID 5006208.

- ^ "Waardenburg syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. October 2012.

- ^ Rogers, J. M. (2016). "Search for the missing lncs: gene regulatory networks in neural crest development and long non-coding RNA biomarkers of Hirschsprung's disease". Neurogastroenterol Motil. 28 (2): 161–166. doi:10.1111/nmo.12776. PMID 26806097. S2CID 12394126.

- ^ Sampson, P. D.; Streissguth, A. P.; Bookstein, F. L.; Little, R. E.; Clarren, S. K.; Dehaene, P.; Graham, J. M. Jr (1997). "The incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of the alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder". Teratology. 56 (5): 317–326. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199711)56:5<317::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 9451756.

- ^ Smith, S. M.; Garic, A.; Flentke, G. R.; Berres, M. E. (2014). "Neural crest development in fetal alcohol syndrome". Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 102 (3): 210–220. doi:10.1002/bdrc.21078. PMC 4827602. PMID 25219761.

- ^ Scambler, Peter J. (2000). "The 22q11 deletion syndromes". Human Molecular Genetics. 9 (16): 2421–2426. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.16.2421. PMID 11005797.

- ^ Ahmed, M.; Ye, X.; Taub, P. (2016). "Review of the Genetic Basis of Jaw Malformations". Journal of Pediatric Genetics. 05 (4): 209–219. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593505. PMC 5123890. PMID 27895973.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). The Neural Crest. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Vega-Lopez, Guillermo A.; Cerrizuela, Santiago; Aybar, Manuel J. (2017). "Trunk neural crest cells: formation, migration and beyond". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 61 (1–2): 5–15. doi:10.1387/ijdb.160408gv. hdl:11336/53692. ISSN 0214-6282. PMID 28287247.

- ^ Takamura, Kazushi; Okishima, Takahiro; Ohdo, Shozo; Hayakawa, Kunio (1990). "Association of cephalic neural crest cells with cardiovascular development, particularly that of the semilunar valves". Anatomy and Embryology. 182 (3): 263–72. doi:10.1007/BF00185519. PMID 2268069. S2CID 32986727.

- ^ Gans, C.; Northcutt, R. G. (1983). "Neural crest and the origin of vertebrates: A new head". Science. 220 (4594): 268–274. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..268G. doi:10.1126/science.220.4594.268. PMID 17732898. S2CID 39290007.

- ^ Northcutt, Glenn (2005). "The new head hypothesis revisited". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 304B (4): 274–297. Bibcode:2005JEZB..304..274G. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21063. PMID 16003768.

- ^ Sauka-Spengler, T.; Bronner-Fraser, M. (2006). "Development and evolution of the migratory neural crest: a gene regulatory perspective". Curr Opin Genet Dev. 13 (4): 360–6. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.006. PMID 16793256.

- ^ Donoghue, P.C.; Graham, A.; Kelsh, R.N. (2008). "The origin and evolution of the neural crest". BioEssays. 30 (6): 530–41. doi:10.1002/bies.20767. PMC 2692079. PMID 18478530.

- ^ Abitua, P. B.; Wagner, E.; Navarrete, I. A.; Levine, M. (2012). "Identification of a rudimentary neural crest in a non-vertebrate chordate". Nature. 492 (7427): 104–107. Bibcode:2012Natur.492..104A. doi:10.1038/nature11589. PMC 4257486. PMID 23135395.

- ^ Kalcheim, C. and Le Douarin, N. M. (1998). The Neural Crest (2nd ed.). Cambridge, U. K.: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Van Keymeulen, A; Mascre, G; Youseff, KK; et al. (October 2009). "Epidermal progenitors give rise to Merkel cells during embryonic development and adult homeostasis". J. Cell Biol. 187 (1): 91–100. doi:10.1083/jcb.200907080. PMC 2762088. PMID 19786578.

- ^ Szeder, V; Grim, M; Halata, Z; Sieber-Blum, M (January 2003). "Neural crest origin of mammalian Merkel cells". Dev. Biol. 253 (2): 258–63. doi:10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00015-5. PMID 12645929.

- ^ Lake, JI; Heuckeroth, RO (1 July 2013). "Enteric nervous system development: migration, differentiation, and disease". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 305 (1): G1–24. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00452.2012. PMC 3725693. PMID 23639815.