Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

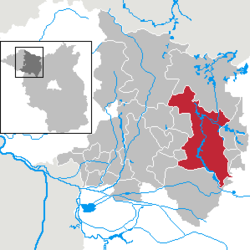

Neuruppin

View on WikipediaNeuruppin (German: [nɔʏʁʊˈpiːn] ⓘ, lit. 'New Ruppin', in contrast to "Old Ruppin"; ; North Brandenburgisch: Reppin) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Ostprignitz-Ruppin district. It is the birthplace of the novelist Theodor Fontane (1819–1898) and therefore also referred to as Fontanestadt. A garrison town since 1688 and largely rebuilt in a Neoclassical style after a devastating fire in 1787, Neuruppin has the reputation of being "the most Prussian of all Prussian towns".[citation needed]

Key Information

Geography

[edit]Geographical position

[edit]Neuruppin is one of the largest cities in Germany in terms of area. The city of Neuruppin, 60 km (37 mi) northwest of Berlin in the district of Ostprignitz-Ruppin (Ruppin Switzerland), consists in the south of the districts located on the shores of Ruppiner See, which is crossed by the Rhin River, including the actual core city of Neuruppin and Alt Ruppin. In the north, it stretches up to the Rheinsberg Lake Region and the border with Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. It is part of the Stechlin-Ruppiner Land Nature Park and is connected to the Wittstock-Ruppiner Heide, which was partly used for military purposes as the Wittstock military training area.

Municipal subdivisions

[edit]After several annexations in 1993, Neuruppin today is one of Germany's largest municipalities by area. The following districts and residential areas belong to Neuruppin since the annexations in 1993.[3]

| Districts | Parts of the municipality | Residences |

|---|---|---|

| Alt Ruppin, Buskow, Gnewikow, Gühlen-Glienicke, Karwe, Lichtenberg, Krangen, Molchow, Neuruppin (Kernstadt, not an official district), Nietwerder, Radensleben, Stöffin, Wulkow, Wuthenow | Binenwalde, Boltenmühle, Kunsterspring, Neuglienicke, Pabstthum, Radehorst, Rheinsberg-Glienicke, Seehof, Steinberge, Stendenitz, Zermützel, Zippelsförde | Alte Schäferei, Ausbau Nietwerder, Ausbau Wulkow, Bechlin, Birkenhof, Bürgerwendemark, Bütow, Dietershof, Ferienpark Klausheide, Fristow, Gentzrode, Gildenhall, Heidehaus, Hermannshof, Lietze, Musikersiedlung, Neumühle, Quäste, Rägelsdorf, Roofwinkel, Rottstiel, Stöffiner Berg, Tornow, Treskow |

In addition, there is the deserted Krangensbrück.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Neuruppin (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.7 (96.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

35.7 (96.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

3.9 (39.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

1.4 (34.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.5 (−8.5) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.4 (1.87) |

33.8 (1.33) |

37.0 (1.46) |

30.4 (1.20) |

48.3 (1.90) |

62.3 (2.45) |

73.4 (2.89) |

55.7 (2.19) |

44.3 (1.74) |

43.7 (1.72) |

40.7 (1.60) |

45.3 (1.78) |

567.3 (22.33) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 16.4 | 14.1 | 13.9 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 12.2 | 13.5 | 15.1 | 17.4 | 169.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 2.6 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 | 9.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87.5 | 85.5 | 82.9 | 79.6 | 78.5 | 78.4 | 78.0 | 77.0 | 79.1 | 82.5 | 86.5 | 87.8 | 81.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 51.5 | 74.3 | 127.5 | 197.1 | 240.5 | 234.7 | 239.6 | 219.8 | 166.8 | 115.5 | 53.2 | 39.4 | 1,764.3 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[4] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather and climate in Neuruppin | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Before the city fire (until 1787)

[edit]

The prehistoric settlement of the country ranges from the Middle Stone Age through the younger Bronze Age with first Germanic, later Slavic settlements (in the old town area - including "Neuer Markt" - and in the surrounding countryside) on the shores of Lake Ruppin. In late Slavic times, this area was settled by the Zamzizi tribe, whose center was probably the Slawenburg Ruppin on the island of Poggenwerder near Alt Ruppin. After the Wendish Crusade in 1147 and the conquest of the land by the German nobility, around 1200 on the Amtswerder, a peninsula next to the island of Poggenwerder, the Ruppin Castle (also Planenburg) was built as a large lowland castle and political center of the Lordship of Ruppin. In the northern foreland a market settlement with Nikolai church developed, east of it and beyond the Rhin the Kietz: the town (Olden Ruppyn) Alt Ruppin had arisen.

Southwest of the castle town, the settlement of today's Neuruppin with Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas' Church) and a street market was established at the beginning of the 13th century, keeping the name Ruppin.

The then (Neu-)Ruppin was a planned town foundation of the counts of Lindow-Ruppin, a collateral line of the Arnsteins, who resided in Alt Ruppin. The first documentary mention dates back to 1238. An expansion of the original Marktsiedlung Alt Ruppin, towards the present-day city of Neuruppin, probably took place before the foundation of the Dominican monastery in 1246 as the first settlement of the order between the Elbe and Oder rivers by the first prior Wichmann von Arnstein. The granting of the Stendal town charter took place on March 9, 1256, by Günther von Arnstein. The city was fortified in the 13th century by palisades and a rampart-ditch system, later it was fortified by walls and rampart-ditches; 24 "Wiekhäuser" and two high towers reinforced the city wall. In addition, there were three gates, the Altruppiner/Rheinsberger Tor in the north, the Berliner/Bechliner Tor in the south and the Seetor in the east. The complete walled enclosure occurred at the latest towards the end of the 15th century.

Neuruppin's oldest part was an elongated Anger, accompanied by two parallel streets between the southern and northern city gates, in the south on it the oldest church of Neuruppin (St. Nikolai). The main street of Neuruppin was pavement since the middle of the 16th century. Across Neuruppin, from the northwest toward the lake, ran the Klappgraben, coming from the Ruppiner Mesche, to supply the city with service water and for drainage, which was partially filled in 1537 and renewed as an open canal in Schinkelstraße after the city fire of 1787.

In the Middle Ages, Neuruppin was one of the larger northeastern German cities. Preserved from this period are, among other things, parts of the city wall, parts of the monastery church of St. Trinitatis (1246), St. George's Chapel (1362), the leprosorium (1490)[5] with the St. Lazarus Chapel consecrated in 1491, as well as remains of the lake district. The medieval city had a nearly square ground plan of about 700 m × 700 m, which blunts conspicuously at the eastern corner. The east-southeast side borders on the Ruppiner Lake.

In 1512, to celebrate a peace treaty, Elector Joachim I organized a three-day jousting tournament in Neuruppin. After the extinction of the Counts of Lindow-Ruppin in 1524, Neuruppin came to the Elector Joachim I as a settled fief. The Thirty Years' War also devastated Neuruppin. In the course of the Reformation, the monastery property fell to the elector around 1540. In 1564, he donated the monastery to the city. During this time, a legend depicted in the monastery church about a mouse chasing a rat, which is interpreted as a sign that the church would remain Lutheran in the future.[6]

A Latin school was first documented in Neuruppin in 1365, which at times had supra-regional importance. Its history is well documented since 1477.[7] In 1777 Philipp Julius Lieberkühn and Johann Stuve took over the school administration and reformed the school in the Basedowsche Sense, which received general attention.

In 1688 Neuruppin became one of the first garrison towns in Brandenburg. It was here that Crown Prince Frederick was imprisoned from 1732 to 1740 after his unsuccessful escape attempt and subsequent imprisonment in Küstrin. Holder of the Regiment on Foot Crown Prince. During this time, Bernhard Feldmann city physicist. His transcripts of historically interesting council records are considered the most important collection of sources on early town history, as the original records were destroyed in the town fire of 1787. At times the number of soldiers and civilian troop members was 1500 out of 3500 inhabitants.[8] Neuruppin only lost this status with the withdrawal of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany.

After 1685, French Huguenots settled there. From 1740 the organ builder Gottlieb Scholtze had his workshop in Neuruppin, who among other things built the organ in Rheinsberg.

City fire and reconstruction (1787-1803)

[edit]A break in the development of the town was the wildfire of Sunday, August 26, 1787. The fire broke out in a barn filled with grain at the Bechliner Tor in the afternoon and spread rapidly. Only two narrow areas on the eastern and western edges of the city remained. A total of 401 bourgeois houses, 159 outbuildings and outhouses, 228 stables and 38 barns, the parish church of St. Mary, the town hall, the Reformed church, and the Prince's Palace were destroyed.[9] Property damage was estimated at nearly 600,000 talers. The Fire Fund replaced about 220,000 thalers, a special church collection yielded 60,000 thalers, and the Prussian Government provided 130,000 thalers of funding for the reconstruction of the city. In total, the state spent over one million thalers in the following years.

The city planning director Bernhard Matthias Brasch (1741-1821), who had been active in the city since 1783, implemented the specifications of the reconstruction commission and supervised the corresponding works. These took place from 1788 to 1803, following a uniformly planned ground plan.[10] Brasch's plan envisaged the expansion of the city from 46 to almost 61 hectares with the removal of the ramparts between the Tempelgarten and the lake. The two north–south streets, which were close together, were united into one axis, later Karl-Marx-Strasse. A rectangular network of streets with continuous two-story troughshouses was created. Long wide streets interrupted by stately plazas, and houses in a transformation architecture mixing Baroque, Mannerist and Gothic design elements with Neoclassical trends,[11][12] have shaped the townscape since that time. These urban reform principles are well recognizable. Thus, with the reconstruction, a classicist city layout unique in this originality was created. The reconstruction was already completed in 1803. Only the completion of the parish church of St. Mary (built 1801-1806 by Philipp Bernard François Berson with the collaboration of Carl Ludwig Engel) dragged on until 1806 due to structural problems.

After the disastrous fire in 1787, the neo-classicism of the rebuilt town's buildings have characterised its townscape to the present day. It remained a garrison town until the late 20th century, since Soviet troops were stationed here until 1993; during this time, there were as many Soviet soldiers as inhabitants in Neuruppin.

Reconstruction in the 19th century (1804-1900)

[edit]

Johann Bernhard Kühn (1750-1826) began producing picture sheets in Neuruppin, thematically designed and for a long time as hand-colored broadsides. His son Gustav Kühn (1794-1868) achieved print runs of sometimes over three million copies per year (e.g., the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71). The prints became known worldwide with the inscription Neu-Ruppin, zu haben bei Gustav Kühn. Three other companies produced the popular picture sheets: Philipp Oehmigke, Hermann Riemschneider, and Friedrich Wilhelm Bergemann. All three picture sheet producers managed to hold their own in the German picture sheet manufacturer competition (more than 60 companies throughout Germany) and to occupy the leading positions for a long time.

From 1815 to 1945, Neuruppin was part of the Prussian Province of Brandenburg. In September 1820, the Infantry Regiment 24 came to Neuruppin with its staff and two battalions, while the Fusilier Battalion took up garrison in Prenzlau.[13] The regiment had been raised elsewhere in 1813, and had participated in the wars of liberation and the occupation of France. Initially, the regiment was housed in Neuruppin burghers' quarters.

In 1877, the organ builder Albert Hollenbach set up his workshop in Neuruppin. His works include organs in the churches of the districts of Bechlin, Buskow, Karwe, Nietwerder and Storbeck as well as the Siechenhauskapelle in the old town of Neuruppin. After 1880, Neuruppin became the center of a branch line network, which was operated by the Ruppiner Eisenbahn AG until 1945. This radiated to Fehrbellin-Paulinenaue (1880), Kremmen-Berlin and Wittstock-Meyenburg (1899), and Neustadt and Herzberg respectively (1905). For this purpose, a railroad embankment was built across the Ruppiner See, cutting across the lake 2.5 kilometers from the north shore in an east–west direction.

In 1893, the Neuruppin State Lunatic Asylum was built on the southern edge of the central city.

The city in the 20th century

[edit]Fire extinguishers have been manufactured in Neuruppin since 1905. Minimax fire extinguishers in particular quickly became widespread due to their ease of use. During World War I, an aviation squadron was stationed in Neuruppin and an airfield was established.[8] In 1921, an open-air settlement was founded in the Gildenhall district by master builder and settlement engineer Georg Heyer (1880-1944), whose goal was to gather artists and artisans to live and work together in order to create and produce everyday products affordable to all and in artisanal form. It attracted many renowned artists and artisans, and existed until 1929.

In 1926, the road next to the railroad embankment across Lake Ruppin was completed. The settlements Gildenhall and Kolonie Wuthenow thus received a direct connection to Neuruppin. In 1929, these settlements were incorporated, after the Treskow estate district had already been incorporated in 1928.[9]

After the Nazis seized power in June 1933, more than 80 political opponents of the regime, mainly Social Democrats, Jews, and Communists, were taken to a provisional prison run by the SA within the buildings of a brewery on Altruppiner Allee, which had been shut down at that time. SA members tortured and mistreated many of the prisoners here. They are commemorated by a memorial stone created during the Soviet occupation in 1947 and by the ensemble of figures created in 1981 at the behest of the SED district leadership, which replaced the original memorial on Schulplatz.

In 1934, the Neuruppin military airfield was revived as the Fliegerschule Neuruppin.

The city's approximately 90 Jewish citizens were persecuted, deported, and murdered during the Nazi era. Their Old Cemetery, established in 1824, was treated relatively leniently; preserved Jewish gravestones were moved to the New Cemetery (Protestant Cemetery) by order of the then regimental commander of the Wehrmacht, Paul von Hase. Since November 17, 2003, Stolpersteine ("stumbling stones") markers in the core city and in Alt-Ruppin have commemorated the murdered Jewish residents.[14]

For the Aktion T4 mass murder campaign of those deemed physically infirm during the National Socialist era, the Neuruppin State Lunatic Asylum served as an intermediate facility for the Brandenburg Euthanasia Centre and the Bernburg Euthanasia Centre. Therefore, the number of patients increased from 1,971 on January 1, 1937, to 4,197 on April 1, 1940. In 1941, only 1,147 of the 1,797 planned beds were still occupied. In 1943, the greater part of the patients were transferred to other institutions in Aktion Brandt.[15] The hospital was also partly used as a reserve hospital during World War II. After 1945, parts of the facility served as a district hospital. On September 20, 2004, six Stolpersteine were laid on the grounds of the Ruppiner Kliniken in memory of the euthanasia victims of the former state lunatic asylum.[14]

On May 1, 1945, Soviet forces reached Neuruppin and prepared to shell the city from the opposite shore of the lake. However, an unknown person managed to raise a white flag on the tower of the monastery church, and the same happened at the parish church. This prevented any destruction.[16] A Soviet cemetery of honor was established north of the Rheinsberger Tor train station, where more than 220 Soviet soldiers were buried.[17]

Neuruppin became one of the largest garrisons of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany (GSSD).[17] The Soviet forces used the military airfield located immediately north of the central city, whose operation caused considerable noise pollution in the city. In 1989, massive demonstrations by Neuruppin residents in connection with plans for the continued use of the Wittstock military training and air-to-ground firing range led to the closure of the airfield.

Until about 1950, the theater Die neue Bühne was located in the city center. It was operated as part of the state association of the German People's Stage and had up to 95 employees.[18]

In 1951, the Elektro-Physikalische Werkstätten was founded in Neuruppin as a producer of electronic components. From 1970, they were expanded as Elektro-Physikalische Werke (EPW) to become the largest printed circuit board manufacturer in the GDR, employing up to 3,500 workers.[19] Later, the plant was an integral part of the Kombinat Mikroelektronik. In the GDR era, the children's summer camp Frohe Zukunft DDR was located in Gühlen-Glinicke.

In 1952, Neuruppin became the district town of the district of the same name in Bezirk Potsdam as a result of the GDR district reform.

As a result of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the peaceful revolution in the GDR, the state of Brandenburg was reestablished in 1990, while the district of Neuruppin remained in existence for the time being.

Neuruppin as a socialist district town 1970-1989

[edit]Plans for the development of a modern district town with up to 100,000 inhabitants were made from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. The basis for this was the planned industrial and administrative development of the district town of Neuruppin. Beginning in the 1970s, VEB Elektrophysikalische Werke Neuruppin was established to handle all printed circuit board production for the GDR's microelectronics and entertainment technology industries. The VEB Feuerlöschgerätewerke Neuruppin, as the main producer of hand-held fire extinguishers for the Eastern Bloc countries united in the CMEA, and the Volkseigene Backwarenkombinat, as the main producer of all kinds of baked goods for the district town and the district of Neuruppin, were expanded considerably.

All this required the influx of highly qualified management, research, and development personnel as well as many thousands of workers. The resident core population of Neuruppin until the end of the 1960s was not sufficient for this. Planning also took into account Neuruppin's convenient location at the intersection of four important branch lines of the Deutsche Reichsbahn with favorable north–south connections for freight and passenger traffic and the Berlin-Rostock/Hamburg highway (now the A24 and A19), which was in planning and later under construction. The plans for a socialist district town included the construction of several residential complexes outside the town's settlement area, which existed until 1968, and the transformation of the old town, which was located outside the medieval city walls. Due to the dwindling economic power of the socialist planned economy of the GDR, only the following urban development projects were implemented from the 1970s onwards:

- Construction of the "VEB Elektrophysikalische Werke Neuruppin".

- Construction of the "Volkseigene Kombinat Backwaren Neuruppin" (People's Own Bakery Combine Neuruppin)

- Expansion of the "VEB Feuerlöschgerätewerk Neuruppin" (VEB fire extinguisher plant)

- 1961: Construction of the polyclinic (Neustädter Straße) for medical care

- 1970-1974: Construction of the housing complex (WK) I Junckerstraße / Thomas-Mann-Straße / Franz-Maecker-Straße (GDR housing construction series IW 64 type Brandenburg / Markkleeberg)

- 1970-1972: Construction of the road axes E-Strasse (initially without a name E-Strasse = relief road around the city center, since 1973 Heinrich-Rau-Strasse) and the feeder roads north and south to the highway (today A 24),

- 1972: Establishment of a public transport system that still operates according to a regular timetable through the Neuruppin city bus line.

- 1972-1974: Construction of the housing complex (WK) II Hermann-Matern-Straße / Erich-Schulz-Straße / August-Fischer-Straße / Anna-Hausen-Straße (GDR housing series IW 64 type Brandenburg / Markkleeberg)

- 1970-1974: construction and opening of children's combinations (crèche and kindergarten) in housing complexes I and II, construction and opening of Polytechnic Secondary School Theodor Fontane / Karl-Liebknecht and Extended Secondary School Karl-Friedrich Schinkel, opening of department stores in housing complexes I and II

- 1978-1980: Expansion of residential complex I through gap construction (GDR housing construction series WBS 70) between WK I (Junckerstraße) and WK II (Hermann-Matern-Straße), as of 1982, the addition of delicatessen, fruit and vegetable store and residential area restaurant in combination with FDJ youth club 019 (today club disco and night bar "Club 019"), construction of the community center in residential complex II as a residential area restaurant, event hall and student dining hall of the POS Theodor Fontane / Karl Liebknecht

- 1980-1991: Construction of the residential complex III (GDR housing construction series WBS 70) Heinrich-Rau-Straße / Bruno-Salvat-Straße / Otto-Grotewohl-Straße / Otto-Winzer-Straße / Rudolf-Wendt-Straße, partly with apartments for senior citizens.

The historic old town of Neuruppin was spared further redesigns during GDR times for reasons of cost. The construction of a four-lane expressway following the model of an automotive city - leading from Fehrbelliner Strasse along the present Regattastrasse via Bollwerk, crossing Seedamm / Steinstrasse, in the direction of Wittstocker Allee[20] - was opposed by financial constraints in the GDR. The relocation of the VEB Feuerlöschgerätewerk Neuruppin and the compensation for the areas and buildings between Bollwerk and the VEB Feuerlöschgerätewerk which had been taken up by the Soviet Army, did not help the economic power of the GDR in the mid-1970s.

The 1970s

[edit]Neuruppin grew from a small town with about 18,000 inhabitants to 33,000 inhabitants between 1970 and 1989 through the settlement and expansion of technology and industry, which was economically significant for the GDR and the RGW states and as exports to the NSW (non-socialist economic area) in exchange for foreign currency, due to an influx of differently educated people from all parts of the GDR. Added to this were the many foreign workers and apprentices from the allied socialist states of Vietnam, Angola, Cuba, and the Soviet armed forces stationed there with around 12,000 men (including their families). Thus, a diverse population developed in the new housing complex developments I to III.

The Old Town of Neuruppin 1980-1990

[edit]For reasons of cost, the old town of Neuruppin was spared the planned modern redesigns, but it deteriorated noticeably by the end of the 1970s. Beginning in the 1980s, the SED of the GDR began to reflect on the cities' historical past. Thus, from 1980 to 1986, the old town of Neuruppin was redeveloped according to the classicist model with the cooperation of then-mayor Harald Lemke.

Future Residential Complex I to III

[edit]Contrary to the trend after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 in the state of Brandenburg, no residential buildings were demolished in residential complexes I to III. All apartments in residential complexes I to III Neuruppin are 100% in municipal or cooperative management (statistics as of 2015) and 99% are rented.

Neuruppin after the incorporation in 1993

[edit]

When the new districts were formed, which came into effect on December 6, 1993, the district of Neuruppin was absorbed into the district of Ostprignitz-Ruppin. On the same day, Neuruppin was significantly enlarged by incorporating the town of Alt Ruppin as well as the communities of Buskow, Gnewikow, Gühlen-Glienicke, Karwe, Krangen, Lichtenberg, Molchow, Nietwerder, Radensleben, Stöffin, Wulkow and Wuthenow. Until 1991, Neuruppin was still the location of the 12th Soviet Armored Division. The barracks were later converted into residential buildings as part of the Expo 2000 outdoor project. Parts of the airfield are now still used for gliding.

In 1996, the then Neuruppin Regional Clinic and the District Hospital passed into the ownership of the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district as parts of the Ruppiner Kliniken GmbH. The Ruppiner Kliniken are thus one of the largest regional employers.[21] The Protestant church districts of Ruppin and Wittstock/Dosse merged in 1998, and Neuruppin lost the seat of the superintendent to Wittstock as a result.

On March 11, 1998, the city was awarded the additional designation of Fontanestadt.[22] On January 1, 2001, the focal public prosecutor's office for corruption was established in Neuruppin as the successor to the department for GDR injustices and district crime. It is responsible for corruption offenses throughout the state of Brandenburg.[23][24]

On September 7, 2002, the 7th Brandenburg Day was held in Neuruppin with approximately 230,000 visitors. In response to the Elbe flood in July 2002 in Saxony, numerous artists such as Udo Lindenberg and Gerhard Schöne donated their fees in support of the flood victims.[25] In May 2009, it became public knowledge for the first time that the groundwater under a new development area at Ruppiner See was contaminated with halogenated hydrocarbons. The district of Ostprignitz-Ruppin, as the responsible environmental authority, admitted to having known about the environmental contamination since 1999 through measurements taken during earlier construction projects.[26]

On May 12, 2011, the iodine-containing thermal brine pool in Neuruppin received the first state recognition of a medicinal spring in the state of Brandenburg.[27] The thermal brine pool is used by the Fontane-Therme on the edge of the old town for wellness operations and heating purposes.

Demography

[edit]-

Development of population since 1875 within the current Boundaries (Blue Line: Population; Dotted Line: Comparison to Population development in Brandenburg state; Grey Background: Time of Nazi Germany; Red Background: Time of communist East Germany)

-

Recent Population Development and Projections (Population Development before Census 2011 (blue line); Recent Population Development according to the Census in Germany in 2011 (blue bordered line); Official projections for 2005–2030 (yellow line); for 2017–2030 (scarlet line); for 2020–2030 (green line)

|

|

|

Territorial status of the respective year, number of inhabitants: as of December 31 (from 1991),[29][30][31] from 2011 on the basis of the 2011 census.

Politics

[edit]City Council

[edit]The city council of Neuruppin comprises 30 city councilors and the full-time mayor. The municipal election on May 26, 2019, with a voter turnout of 49.0%, resulted in the following:[32]

| Party / Voter group | Share of votes | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| CDU | 18,6 % | 6 |

| SPD | 18,1 % | 6 |

| Die Linke | 15,9 % | 5 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 13,1 % | 4 |

| Pro Ruppin | 12,8 % | 4 |

| AfD | 10,9 % | 2 |

| Freie Wähler | 4,5 % | 1 |

| Wählergruppe Kreisbauernverband | 3,8 % | 1 |

| FDP | 2,3 % | 1 |

The AfD accounted for four seats in line with its share of the vote, two of which remain unoccupied because the party nominated only two candidates. The CDU and FDP have joined forces to form a parliamentary group, as have Bündnis 90/Die Grünen and the voters' group Kreisbauernverband.

Mayors

[edit]Before the city reform

[edit]- around 1786: Goering[9]

After the city reform in 1808

[edit]

|

After the annexations in 1993

[edit]- 1994–2004: Otto Theel

- 2005-2020: Jens-Peter Golde

- since 2020: Nico Ruhle

Ruhle was elected to an eight-year term in the November 29,[34] 2020 mayoral runoff election with 56.7% of the valid votes.[35]

Dealing with corruption

[edit]In 2004, Neuruppin made headlines for corruption and nepotism. In view of the growing scandals in local politics, the city acquired derogatory nicknames such as "Märkisches Palermo" or "Klein Palermo"[36] and "Korruppin" as it struggled with battling corruption.[37][38]

The former CDU city councilor Olaf Kamrath was legally sentenced in 2006 as the head of the XY gang to many years in prison for, among other things, gang-related narcotics offences.[37] In 2007, the verdict against former city councilor Reinhard Sommerfeld (Neuruppiner Initiative) was the only legally binding conviction of an elected official in Germany for bribery of members of parliament to date.[39] The former state parliament member Otto Sommerfeld was convicted of bribery of members of parliament.

On May 15, 2008, former state parliament member Otto Theel (Die Linke) was given a nine-month suspended prison sentence for taking advantage in office during his term as mayor of Neuruppin. He subsequently resigned his seat in the state parliament.[40] In September 2008, Sparkasse Ostprignitz-Ruppin parted ways with its previous CEO Josef Marckhoff, who had his employer throw him a circa 55,000 euro celebration to mark his own 60th birthday. The date coincided with the company's 160th anniversary.[37]

The former managing director of the municipal public utility company Neuruppin Dietmar Lenz was sentenced to a suspended prison sentence of two years on March 19, 2009, on charges of a serious breach of trust and acceptance of benefits, having spent more than 500,000 euros bypassing the supervisory board to support the sports club MSV Neuruppin. At the end of 2009 he committed suicide.[41] A citizens' initiative initiated with the help of the two relevantly previously convicted Otto Theel and Reinhard Sommerfeld a deselection petition against Mayor Jens-Peter Golde. Golde was accused by the citizens' petition "Kein weiter so!" of lacking leadership quality, failing to fulfill his election program and endangering jobs in Neuruppin. It failed by its own account in February 2010 with 5079 of the required 5300 signatures.[38][42]

As of January 1, 2016, Neuruppin became the sixth corporate municipal member of Transparency International, along with Bonn, Hamm (Westphalia), Potsdam, Leipzig, and Halle (Saale).[43]

Neuruppin remains colorful

[edit]In the run-up to a planned demonstration of radical right-wing groups in the core city of Neuruppin on September 1, 2007, the non-partisan action alliance Neuruppin bleibt bunt formed and organized a counter-event with about 1000 participants.[44][45] On September 5, 2009, in view of another planned demonstration of radical right-wing groups, the action alliance organized a series of actions for civil courage along the demonstration route.[46] On March 27, 2010, Neuruppin bleibt bunt organized the democracy festival Demokratie im Quadrat with 2,000 participants in the face of a demonstration march by the radical right-wing Freie Kräfte Neuruppin with 350 participants.[47]

On June 6, 2011, the action alliance received the Band für Mut und Verständigung award for its work. In November 2011, a party convention of the NPD took place in Neuruppin under protest of Neuruppin bleibt bunt against the will of the city.[48] The action alliance was able, through broad civil society engagement, with cultural stage program on the school square and a blockade for the first time to stop the so-called "Day of the German Future". The far-right Freie Kräfte Neuruppin/Osthavelland had organized the demonstration for June 6, 2015.[49]

Coat of arms

[edit]In § 2 para 1 and 2 of the main statutes of the city of Neuruppin[50] states:

The city has been granted the right to bear a coat of arms by a document of the Prussian State Ministry dated June 22, 1928.

The coat of arms was confirmed on March 31, 2003.

Blazon: "In blue a silver castle with two pinned, two-storey towers with two superimposed black gates and gold-knobbed, red pointed roofs; the central building with three turrets and a black gate, which is covered by a red triangular shield, topped with a gold-armed and gold-tongued silver eagle.".[51] The eagle is the heraldic animal of the Arnstein noble family.[52]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Neuruppin is twinned with:[53]

Babimost, Poland

Babimost, Poland Bad Kreuznach, Germany

Bad Kreuznach, Germany Certaldo, Italy

Certaldo, Italy Niiza, Japan

Niiza, Japan Nymburk, Czech Republic

Nymburk, Czech Republic

Notable people

[edit]

- Joachim Ludwig Schultheiss von Unfriedt (1678–1753), architect

- Karl Friedrich von dem Knesebeck (1768–1848), Prussian field marshal

- Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841), architect

- Ferdinand Möhring (1816–1887), composer

- Theodor Fontane (1819–1898), novelist and poet

- Otto Friedrich Ferdinand von Görschen (1824–1875), lieutenant colonel

- Paul Carl Beiersdorf (1836–1896), pharmacist and founder of Beiersdorf AG

- Johannes Kaempf (1842–1918), politician, president of Reichstag

- Carl Großmann (1863–1922), serial killer

- Ferdinand von Bredow (1884–1934), Major General of Reichswehr

- Hermann Hoth (1885–1971), army commander and war criminal

- Klaus Schwarzkopf (1922–1991), actor

- Horst Giese (1926–2008), actor

- Eva Strittmatter (1930–2011), writer

- Jörg Hube (1943–2009), actor

- Uwe Hohn (born 1962), javelin thrower

- Ulrich Papke (born 1962), canoeist

- Bernd Gummelt (born 1963), race walker

- Jens-Peter Herold (born 1965), middle-distance runner

- Ralf Büchner (born 1967), gymnast

- Timo Gottschalk (born 1974), rally navigator

- Hans Bettembourg, Weightlifter

Associated with the town

[edit]- Frederick the Great (1712–1786), lived in Neuruppin in his years as crown prince of Prussia

- Carl Phillip Gottlieb von Clausewitz (1780–1831), Prussian general and military strategist, resided in Neuruppin for a few years

Gallery

[edit]-

Schinkel statue

-

Statue by Matthias Zágon Hohl-Stein

-

Manor house of the family Gentz in Gentzrode

-

Ruppiner Lake with monastery church towers

-

″Sabine" in Binenwalde

-

Neumühle

-

Trinitatiskirche

-

Former fire extinguisher factory

References

[edit]

- ^ Landkreis Ostprignitz-Ruppin Wahl der Bürgermeisterin / des Bürgermeisters, accessed 2 July 2021.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Municipalities > Ostprignitz-Ruppin District > City of Neuruppin. Archived 2019-04-01 at the Wayback Machine Territorial status: 1 January 2009, Ministry of the Interior of the State of Brandenburg (service portal of the state administration); retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2010". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ The infirmary hospital served, among other things, the treatment of lepers. See also the data of the Gesellschaft für Leprakunde with an overview of all medieval leprosoriums in Berlin and Brandenburg at http://www.muenster.org/lepramuseum/tab-bra.htm

- ^ Theodor Fontane (1892-03-09), "Neuruppin – 1. Ein Gang durch die Stadt. Die Klosterkirche.", Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg – Erster Teil: Die Grafschaft Ruppin (in German), Berlin

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Heinrich Begemann: Die Lehrer der Lateinischen Schule zu Neuruppin 1477-1817. Beilage zum Jahresbericht Friedrich-Wilhelms-Gymnasium zu Neuruppin, Neuruppin, 1914.

- ^ a b Johannes Schultze (1995), Geschichte der Stadt Neuruppin / von Johannes Schultze (in German), Berlin: Stapp, ISBN 3-87776-931-4

- ^ a b Mario Alexander Zadow (2001), Karl Friedrich Schinkel – Ein Sohn der Spätaufklärung (in German), Stuttgart/London: Edition Axel Menges, ISBN 3-932565-23-1

- ^ Ulrich Reinisch: The Reconstruction of the City of Neuruppin after the Great Fire of 1787 or: how the Prussian bureaucracy built a city. Reconstructed and explained according to the files = Forschungen und Beiträge zur Denkmalpflege im Land Brandenburg 3. Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2001. ISBN 978-3-88462-173-8

- ^ Ulrich Reinisch (2001), Der Wiederaufbau der Stadt Neuruppin nach dem grossen Brand 1787 oder wie die preussische Bürokratie eine Stadt baute (in German), Berlin, pp. 190-199, ISBN 3-88462-173-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Brigitte Meier (2004), Fontanestadt Neuruppin: Kulturgeschichte einer märkischen Mittelstadt (in German), Karwe: Edition Rieger, p. 131, ISBN 978-3-935231-59-6

- ^ Franz von Zychlinski: Geschichte des 24. Infanterie-Regiments, Band 2 (1816–1838, urn:urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10595378-7:{{{2}}}). Mittler, Berlin 1908, S. 36.

- ^ a b Rainer Fellenberg (2008-05-04). "Stolpersteine in Neuruppin". Vorbereitungskreis Stolpersteine in Neuruppin. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ Heinz Faulstich (1998), Hungersterben in der Psychiatrie 1914-1949 (in German), Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus, ISBN 3-7841-0987-X

- ^ Gemeindekirchenrat Neuruppin, ed. (1986-12-15), Die Pfarrkirche St. Marien zu Neuruppin - Ihre Zerstörung vor 200 Jahren und ihr Neubau (in German), Neuruppin

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Der sowjetische Ehrenfriedhof in der Fontanestadt Neuruppin". Berlins Taiga - Dein Ausflugsbegleiter in die sowjetische Geschichte. 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- ^ Markus Kluge: Altes Neuruppiner Theater wird erforscht und Eine Theatergeschichte ohne Happy End, in: Ruppiner Anzeiger 26 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Brigitte Meier: Fontanestadt Neuruppin – Eine Stadtgeschichte in Daten, Karwe 2003.

- ^ Büro für Städtebau beim Rat des Bezirkes Potsdam: Generalbebauungsplan-Neuruppin, Präzisierung 1980, Leitlinienplanung Wohnkomplex III, Plan der Einordnung in die Gesamtstadt, Plannummer 218/255: rot gestrichelte Linie

- ^ Geschichte. Archived 2022-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Ruppiner Kliniken GmbH; retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Verleihung der Zusatzbezeichnung Fontanestadt. Bekanntmachung des Ministeriums des Innern vom 11. März 1998. Amtsblatt für Brandenburg Gemeinsames Ministerialblatt für das Land Brandenburg, 9. Jahrgang, Nummer 13, 9. April 1998, S. 407

- ^ "Schwerpunktstaatsanwaltschaft Neuruppin". Archived from the original on 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) gesehen am 25. Januar 2011 - ^ "Schwerpunktstaatsanwaltschaft für Korruption Neuruppin", Ruppiner Anzeiger (in German), 2011-01-25

- ^ "Der traditionelle Brandenburg-Tag". Archived from the original on 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), retrieved 28 February 2010. - ^ Alexander Fröhlich: Verseuchtes Grundwasser - Anzeigen gegen Umweltbehörde, Tagesspiegel 23 June 2009, retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ "Pressemitteilung des Ministeriums für Umwelt, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz Brandenburg vom 12. Mai 2011". Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Detailed data sources are to be found in the Wikimedia Commons.Population Projection Brandenburg at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Historisches Gemeindeverzeichnis des Landes Brandenburg 1875 bis 2005. Landkreis Ostprignitz-Ruppin (PDF) S. 18–21

- ^ Bevölkerung im Land Brandenburg von 1991 bis 2017 nach Kreisfreien Städten, Landkreisen und Gemeinden, Tabelle 7

- ^ Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (Hrsg.): Statistischer Bericht A I 7, A II 3, A III 3. Bevölkerungsentwicklung und Bevölkerungsstand im Land Brandenburg (jeweilige Ausgaben des Monats Dezember)

- ^ Ergebnis der Kommunalwahl 26 May 2019

- ^ Petra Torjus (Hrsg.): Elf Frauen die Neuruppin bewegten, Neuruppin 2011.

- ^ "Wahlergebnisse der Bürgermeister*innenwahlen 2020". Neuruppin.de. Fontanestadt Neuruppin vertreten durch den Bürgermeister Jens-Peter Golde. 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- ^ "Brandenburgisches Kommunalwahlgesetz". Brandenburg.de. 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ^ Diana Teschler. "Wie der XY-Fall die Stadt geprägt hat". Info Radio Berlin 9. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- ^ a b c Alexander Fröhlich: Stadt unter Filz, Tagesspiegel published 17 September 2008, retrieved on 12 August 2022.

- ^ a b Zuletzt Alexander Fröhlich: Tagesspiegel published 7 February 2010, retrieved on 12 August 2022.

- ^ Andreas Vogel: "Sommerfeld muss Mandat abgeben Bundesgerichtshof lehnt Revision ab / Urteil wegen Bestechlichkeit damit rechtskräftig". Archived from the original on 2011-05-27. Retrieved 2022-08-12. In: Märkische Allgemeine, Dosse Kurier, 20 October 2007.

- ^ Links-Abgeordneter Otto Theel tritt nach Verurteilung zurück, Tagesspiegel 21 May 2008.

- ^ "Der langjährige Neuruppiner Stadtwerke-Chef nahm sich selbst das Leben". Archived from the original on 2011-05-27. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), MAZ 30 December 2009. - ^ Bürgerbegehren "Kein weiter so!", Presseerklärung 8 February 2010.

- ^ Beitritt als kommunales Mitglied bei Transparency International zum 1 January 2016 (PDF; 93 kB) Neuruppin.de

- ^ Neuruppin bleibt bunt

- ^ "Aktionsbündnis Neuruppin bleibt bunt". Archived from the original on 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Kultur gegen Neonazis, MAZ 28 August 2009". Archived from the original on 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Retrieved 23 September 2015. - ^ Tausendfach Protest gegen Rechtsextreme, Schweriner Volkszeitung 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Neuruppin demonstriert gegen NPD-Parteitag". sueddeutsche.de. 2011-11-12. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ "Kein Durchkommen für Neonazis – Tag der deutschen Zukunft dieses Jahr in Neuruppin erstmals blockiert". neues-deutschland.de. 2016-06-08.

- ^ "Hauptsatzung der Stadt Neuruppin. (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Fontanestadt Neuruppin, 8 July 2005 in Gestalt der 3. Änderungssatzung 6 March 2007: retrieved 30 December 2009. - ^ Kommunen > Stadt Neuruppin > Wappen Stadt Neuruppin Ministerium des Innern des Landes Brandenburg (Dienstleistungsportal); retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Logo und Wappen auf neuruppin.de; retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Neuruppin und seine Partnerstädte". neuruppin.de (in German). Neuruppin. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Neuruppin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Neuruppin at Wikimedia Commons

Neuruppin

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and administrative divisions

Neuruppin lies in the northwestern portion of Brandenburg, Germany, about 60 km northwest of Berlin, serving as the administrative center of the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district.[5] Positioned on the southwestern shore of the Ruppiner See, a lake spanning 8.25 km² at 36.5 m above sea level, the town occupies geographical coordinates of approximately 52°56′ N, 12°48′ E.[6][7] The municipality covers 303.34 km², encompassing diverse landscapes from urban core to surrounding rural and forested areas.[6] Administratively, Neuruppin functions as the seat of the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district, established in 1993 through the merger of former districts including Neuruppin.[8] The town itself comprises 13 Ortsteile (districts), integrated via Brandenburg's 1993 communal reform to form the expanded municipality.[9] These include Alt Ruppin, Bechlin, Buskow, Gnewikow, Gühlen-Glienicke, Karwe, Krangen, Lichtenberg, Molchow, Nietwerder, Radensleben, Stöffin, and Wuthenow, blending the historic core with peripheral villages and nature reserves like the uninhabited Neukammerluch and Redernluch areas focused on groundwater protection.[9] This structure supports regional governance, with the districts maintaining local identities while unified under Neuruppin's administration.[10]Climate and natural environment

Neuruppin lies within a temperate continental climate zone, classified as Cfb under the Köppen-Geiger system, featuring mild to warm summers and cold winters with moderate precipitation distributed throughout the year.[11] Annual average precipitation totals approximately 691 mm, with higher rainfall in summer months supporting regional vegetation. Mean temperatures range from a winter low of about -2°C (28°F) in January to a summer high of 24°C (76°F) in July, with extremes rarely exceeding 31°C (87°F) or dropping below -11°C (12°F).[11] The natural environment surrounding Neuruppin is dominated by the Ruppiner Seenland, a landscape of interconnected lakes, including the Ruppiner See—the longest lake in Brandenburg at 14 kilometers—fringed by mixed deciduous and coniferous forests.[12] This area forms part of the Stechlin-Ruppiner Land Nature Park, spanning 680 square kilometers and characterized by beech woodlands, clear-water lakes, and diverse habitats that include eight nature reserves, two bird protection areas, and 25 Flora-Fauna-Habitat (FFH) sites under EU directives.[13][14] The region's glacial origins contribute to its post-glacial kettle lakes and rolling terrain, known locally as Ruppiner Switzerland, fostering biodiversity with priority species protections and recreational opportunities like swimming in natural bathing areas.[15]History

Pre-modern foundations and growth until 1787

The settlement that would become Neuruppin emerged around 1200 on a peninsula in the Ruppiner See lake following the German conquest of Wendish territories after the 1147 Wendish Crusade.[16] The first documentary mention of Neuruppin dates to 1238, when local nobleman Günter I von Arnstein, ruling the Lordship of Ruppin established circa 1214, referenced the site in records related to regional feudal holdings centered on the town.[17] In 1246, the von Arnstein family founded the region's first Dominican monastery in the Margraviate of Brandenburg, constructing the Sankt Trinitatis church alongside it, which survives as the oldest architectural remnant and indicates early religious and economic consolidation around lake trade routes.[18] Neuruppin received urban charter in 1256 from Count Günter von Arnstein, granting Stendal town rights that formalized its status as a trading hub for agriculture, fishing, and crafts in the Ruppiner Land, elevating it among northeastern Germany's larger medieval cities with preserved city walls, gates, and a hospital founded circa 1362 (expanded 1478).[19] The Lordship of Ruppin, under von Arnstein control until its 1480 sale to Elector Albrecht Achilles of Brandenburg for 24,000 guilders, provided administrative stability, fostering growth through fortified markets and monastic influence until Brandenburg's direct incorporation shifted oversight to Hohenzollern margraves. By the 17th century, Neuruppin had developed as the economic core of Ruppin, with timber-framed burgher houses, breweries, and linen production supporting a population expansion tied to Prussian absolutist policies under the Great Elector Frederick William, who in 1688 established a permanent garrison of dragoons to secure the northeastern frontier against Swedish and Polish threats.[18] Military presence spurred infrastructure like barracks and enhanced trade, yielding circa 4,000 residents by the late 18th century amid steady mercantile growth, though recurrent plagues and wars constrained faster urbanization.[20] Under Frederick the Great from 1740, royal inspections and subsidies further integrated Neuruppin into Prussian networks, emphasizing its role as a regional administrative and provisioning center without significant industrial shifts prior to 1787.[21]Reconstruction following the 1787 fire (1787-1803)

On August 26, 1787, a massive fire devastated Neuruppin, destroying over two-thirds of the town's burgher houses, both principal churches, and the Rathaus, leaving much of the Kurmark provincial town in ruins.[22] The Prussian administration responded swiftly, initiating a state-directed reconstruction known as the Retablissement, which emphasized bureaucratic oversight, standardized planning, and fire-preventive measures to prevent recurrence.[23] This process, beginning in 1788, involved detailed post-fire surveys, cartographic mapping, and zoning regulations enforced by provincial authorities, marking a prototypical example of enlightened absolutist urban renewal under Frederick William II.[24] The rebuilding prioritized rational urban design, widening streets for better access and ventilation, mandating tile roofs over thatch to reduce fire risks, and enforcing uniform setbacks for buildings to create open spaces.[24] Architectural guidelines drew from emerging Neoclassical principles, shifting from the town's medieval timber-frame core to more durable brick structures with simplified facades, though implementation varied due to local builders' adherence and resource constraints.[23] Prussian officials, including engineers and fiscal overseers from Potsdam, coordinated material procurement and lot reallocation, compensating affected owners through state loans and timber from royal forests, while suppressing ad-hoc rebuilding to enforce the master plan.[22] By 1803, core residential and public zones had been substantially restored, with over 200 new houses erected and key infrastructure like widened thoroughfares operational, though some peripheral and ecclesiastical projects extended into the early 1800s amid ongoing bureaucratic reviews and wartime disruptions from the Napoleonic era.[22] This phased completion preserved Neuruppin's garrison function while embedding Prussian administrative efficiency, resulting in a grid-like layout that endures in the Altstadt's spatial organization.[24] The effort, documented extensively in archival protocols, highlighted the central state's capacity for large-scale intervention but also tensions between uniform edicts and local economic realities.[23]Industrialization and Prussian integration in the 19th century (1804-1914)

The Prussian reforms initiated after the Napoleonic defeats, including the emancipation of serfs between 1811 and 1821, indirectly supported Neuruppin's rural hinterland by dismantling feudal obligations and promoting market-oriented agriculture around the Ruppiner Lake, though direct urban impacts were limited to enhanced trade linkages. Neuruppin's administrative integration into the newly formalized Province of Brandenburg solidified in 1815 via the Congress of Vienna, placing it under the Regierungsbezirk Potsdam and aligning local governance with centralized Prussian bureaucracy, which emphasized fiscal efficiency and military readiness over rapid urban expansion. This era saw the town function primarily as a stable garrison outpost rather than an industrial hub, with the Prussian army's presence providing economic stability through soldier expenditures and infrastructure maintenance. Military significance deepened in September 1820 when the staff and units of Infantry Regiment No. 24 established quarters in Neuruppin, expanding the longstanding garrison tradition dating to 1688 and reinforcing the town's role in Prussia's conscript-based defense system amid post-Napoleonic reorganization. The regiment's stationing contributed to local employment in support services, barracks construction, and provisioning, comprising a key non-agricultural economic pillar amid Brandenburg's overall agrarian dominance. By mid-century, Neuruppin's neoclassical rebuilt core—featuring broad streets and public buildings—exemplified Prussian ideals of orderly urban planning, with ongoing investments in fortifications and drill grounds underscoring integration into the kingdom's martial priorities. Economic activity pivoted toward specialized light industry, notably printing and lithography, as Neuruppin emerged as a European center for Bilderbogen (illustrated broadsheets) in the mid-19th century. Firms such as Oehmigke & Riemschneider, founded in 1831, mass-produced colorful lithographic sheets depicting folklore, battles, and daily life, achieving widespread export and employing skilled artisans in an era when heavy manufacturing bypassed the town. Three major printing works dominated this sector, leveraging the town's educated workforce and proximity to Berlin markets to produce the era's proto-mass media, though output remained artisanal rather than mechanized on the scale of Rhineland factories. Rail infrastructure marked a pivotal modernization step, with the Paulinenaue-Neuruppiner Eisenbahn opening on September 12, 1880, linking Neuruppin to the Berlin metropolitan area and enabling efficient goods transport for printing outputs and agricultural products. Subsequent extensions, including the Kremmen-Neuruppin line operational by December 16, 1898, integrated the town into Prussia's expanding rail network under state oversight, fostering commuter flows and minor factories for wood processing and machinery repair without triggering transformative industrialization. This connectivity supported steady population growth and trade volumes, positioning Neuruppin as a secondary Prussian nodal point by 1914, though its economy retained a pre-industrial character dominated by military, commerce, and niche manufacturing.World wars, Nazi era, and early postwar division (1914-1949)

During World War I, Neuruppin contributed to the German military effort as a longstanding garrison town, hosting an aviation squadron and seeing the establishment of a local airfield around 1916 for training and operations.[25] The interwar Weimar Republic brought economic strains, fostering early support for the NSDAP in the Ruppin district, where the party achieved 30.5% in the 1930 local elections, surpassing the SPD's 28.3%.[26] By the July 1932 presidential election's first round, NSDAP candidate Adolf Hitler received 48% of votes in the area, exceeding national trends, reflecting rural and small-town appeal amid agrarian discontent and unemployment.[26] Following Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Neuruppin witnessed immediate Nazi mobilization, including a torchlight parade on January 31 involving 450 SA members and 350 Stahlhelm participants.[26] In the March 12, 1933, communal elections—conducted under intimidation—the NSDAP secured 16 of 21 seats in the city parliament and 17 of 22 in the district council, enabling rapid consolidation of power.[26] Local opposition faced suppression, as seen in the June 1933 public parading and subsequent transfer to a concentration camp of KPD member Erich Schulz, and the April 1933 public shaming of resident Gertrud Koß for not rising during the Horst-Wessel-Lied.[26] The central Schulplatz was renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz on April 20, 1933, symbolizing Nazi control over public space.[26] The psychiatric Landesanstalt Neuruppin functioned as a Zwischenanstalt in the T4 euthanasia program from 1940, transferring patients to killing facilities like Hartheim and Bernburg, contributing to the regime's systematic murder of around 200,000 disabled individuals nationwide under the guise of mercy killing and racial hygiene.[27] World War II brought aerial bombings to Neuruppin, with raids in April 1945 inflicting casualties buried at the Evangelical Cemetery.[28] The town also marked the April 1945 death march evacuations from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where thousands of prisoners perished en route, commemorated locally.[29] On May 1, 1945, Soviet forces of the Red Army occupied Neuruppin with minimal destruction, as local residents negotiated a bloodless handover to avert artillery bombardment.[28][30] In the immediate postwar years, Neuruppin lay in the Soviet Occupation Zone, subjecting it to denazification processes, resource shortages, and administrative purges under military government oversight.[31] As part of Brandenburg province, the town faced the escalating East-West divide, with Soviet policies prioritizing reparations and ideological reorientation, culminating in the formation of the German Democratic Republic on October 7, 1949.GDR socialist development and urban expansion (1949-1990)

Following the establishment of the German Democratic Republic in 1949, Neuruppin's economy underwent nationalization, with private enterprises converted into volkseigene Betriebe (VEBs) aligned with central planning priorities of heavy industry and consumer goods production for the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA).[32] A prominent example was the VEB Feuerlöschgerätewerke Neuruppin, which by 1949 had resumed production at 116,000 hand-held fire extinguishers annually, eventually becoming the GDR's primary manufacturer for export to Eastern Bloc countries.[33] Other VEBs included those for baked goods (VEB Backwaren Neuruppin) and prefabricated housing components (VEB Fertighausbau Neuruppin), supporting local construction and food supply chains amid postwar shortages.[32] These state-owned operations emphasized labor-intensive manufacturing, with employment tied to quotas set by the Socialist Unity Party (SED), though inefficiencies in resource allocation limited output growth compared to prewar levels. Urban expansion accelerated in the 1970s under GDR housing policies, which prioritized prefabricated concrete panel buildings (Plattenbauten) to accommodate industrial workers and address postwar deficits. In Neuruppin, these modular structures, often in variants like the "Erfurt" type for schools and residences, were erected in peripheral districts to house families, with residents reporting occupancy starting around 1974-1975.[34] [35] Despite SED directives for rapid urbanization, Neuruppin's projects remained modest relative to larger GDR cities, focusing on functional expansion rather than monumental socialist-realist architecture, constrained by material shortages and centralized material distribution. Population within current boundaries grew steadily during this era, reflecting inward migration for VEB jobs and state-subsidized housing, though exact figures varied by census adjustments for administrative mergers.[19] By the 1980s, Neuruppin's socialist framework emphasized self-sufficiency in basic goods and fire safety equipment, but chronic underinvestment in infrastructure—evident in aging utilities and limited mechanization—highlighted systemic rigidities, as production lagged behind Western standards despite CMEA integration.[33] The town's role as a district center (Kreisstadt Neuruppin until 1990) reinforced SED control through local party structures, with urban planning subordinated to ideological goals like collectivized agriculture in surrounding areas, which supplied VEBs but yielded variable harvests due to soil limitations in the Ruppiner Land.[32] Overall, while VEBs drove modest employment gains, the period's development prioritized quantity over quality, setting the stage for post-1990 economic disruptions.Reunification challenges and modern adaptation (1990-present)

Following German reunification in 1990, Neuruppin faced significant economic disruptions typical of former East German towns, including the rapid closure of state-owned enterprises and the withdrawal of Soviet military forces. The Elektrophysikalische Werke, a major GDR-era employer, shut down, resulting in the loss of approximately 3,500 jobs. Additionally, the departure of around 15,000 Soviet soldiers from local barracks by 1991 eliminated associated economic activity, such as supply contracts and services, exacerbating short-term unemployment and fiscal strain. These shocks contributed to a regional uptick in joblessness, though Neuruppin's administrative role as district seat provided some buffer compared to more industrialized areas.[36] In response, the town pursued structural reforms, developing the Treskow industrial park starting in 1991, which by the 2020s hosted about 50 companies and generated new employment in manufacturing and logistics. Public debt, peaking at €32 million in 1995 amid transition costs, was reduced to €11 million by 2020 through fiscal discipline and EU-funded projects, with goals for debt elimination by 2030. The healthcare sector adapted via modernization of the Ruppiner Kliniken, evolving from DDR infrastructure into a university-affiliated facility with expansions like Haus X in 2007, sustaining jobs and attracting investment. Local firms, such as Herrmann GmbH founded in 1990, expanded from niche operations to 30 employees by leveraging markets in solar technology.[36][37] Urban renewal addressed dilapidated GDR-era housing and infrastructure, with over €48 million invested in the inner city by 2018, revitalizing trade and residential areas. Projects like the Sonnenufer development converted former industrial sites into 180 housing plots by 2014, while historical sites such as the Alte Gymnasium were restored with €7 million in EU funds from 2009 to 2011. Population remained relatively stable, growing from 27,002 in 1990 to around 32,000 by the mid-2000s before stabilizing with a net gain of 550 residents from 2010 to 2021, contrasting sharper declines in surrounding Brandenburg areas due to Neuruppin's service-oriented economy and commuter links to Berlin. Tourism emerged as a growth driver, capitalizing on the "Fontanestadt" designation since 1998 and Ruppiner See amenities, drawing 36,000 museum visitors in 2019.[38][39][36] Social challenges included efforts to counter right-wing extremism, addressed through initiatives like "Neuruppin bleibt bunt" launched in 2007 to promote integration and cultural diversity. By the 2010s, sustainability measures advanced, with Neuruppin's utilities targeting climate-neutral energy amid national renewable trends. The Neuruppin Strategie 2030 outlined continued focus on balanced growth, emphasizing digital infrastructure and regional connectivity to mitigate ongoing East-West disparities.[36][40]Demographics

Historical population dynamics

The population of Neuruppin grew gradually in the 18th century, reaching approximately 3,500 inhabitants around 1720, 6,382 by 1770, and 6,047 by 1800, with the slight decline attributable to the destructive fire of 1787 that razed much of the town.[41] Recovery accelerated in the mid-19th century, with records showing 8,000 residents in 1840, 10,000 in 1846, and over 11,000 by 1871, driven by post-fire reconstruction and early industrial activities.[20] Industrialization and Prussian administrative integration fueled sustained expansion from the late 19th century, with the population increasing from 12,706 in 1875 to 14,712 in 1890 and 18,920 by 1910, reflecting urban development and infrastructure improvements such as railway connections.[42] Growth slowed during and after World War I, stabilizing at 19,014 in 1925 and rising modestly to 21,291 in 1933 amid economic challenges of the Weimar Republic. Under Nazi rule, policies promoting internal migration and territorial adjustments within current boundaries elevated the figure to 24,559 by 1939.[42] World War II brought destruction but also a postwar surge from displaced Germans fleeing Soviet-occupied eastern territories, peaking at 36,677 in 1950.[42] In the German Democratic Republic era, population fluctuated with socialist industrialization and housing projects; it dipped to 31,422 by 1964 due to selective out-migration and administrative boundary changes, then recovered to 33,042 in 1981 and 34,014 by 1990 through urban expansion and state-directed settlement.[42] After German reunification, economic disparities prompted significant out-migration to western states, causing a decline from 34,014 in 1990 to around 31,000 by the 2010s, stabilizing at 31,421 according to the 2022 census, below the Brandenburg state average growth due to persistent regional depopulation trends in former East Germany.[43][42]Current composition, migration patterns, and social integration

As of December 31, 2024, Neuruppin had a resident population of 32,656, marking a net increase of just five individuals from the previous year amid ongoing low birth rates and modest in-migration.[44] The demographic makeup remains predominantly ethnic German, reflecting patterns in eastern Germany where native-born residents form the vast majority. Foreign nationals comprised over 1,500 individuals in 2020, equating to roughly 5% of the then-population of approximately 31,000; district-level data from Ostprignitz-Ruppin suggest this proportion has held steady or slightly risen, with foreign passport holders accounting for 5.3% of the local workforce as of recent reports.[45] [46] Migration patterns indicate limited inflows, primarily driven by labor needs in local industries and asylum-related arrivals rather than large-scale family reunification or economic migration from non-EU countries. In the broader Ostprignitz-Ruppin district, 4,406 foreigners from 113 nations resided as of 2020, contributing to a gradual stabilization of population decline through positive migration balances that offset natural decrease. Neuruppin's minimal 2023–2024 growth aligns with Brandenburg's trends, where immigration has prevented sharper depopulation but remains below western German levels, with net gains concentrated in working-age adults filling employment gaps.[47] Social integration initiatives emphasize practical support for refugees and migrants, including volunteer-driven language and orientation programs coordinated by local authorities and networks like the Bündnis für Integration. Businesses in Neuruppin report dependence on foreign workers, fostering economic incentives for inclusion, while a 2024 survey of regional actors showed 76.1% participation in refugee aid efforts, highlighting community involvement despite occasional tensions in an area with historical right-wing sentiments. The town actively pursued additional refugee intakes in 2020, offering capacity for 50–75 from crisis zones like Moria, underscoring localized efforts to leverage migration for demographic and labor sustainability.[48] [49][50]Economy

Key industries and employment sectors

Neuruppin serves as the economic center of northern Brandenburg, hosting approximately 1,200 companies and emphasizing manufacturing sectors such as plastics, automotive components, wood processing, food production, and paper alongside tourism.[51] The healthcare sector stands out as the dominant employer in the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district, which Neuruppin anchors, with the Ruppiner Kliniken GmbH employing around 2,000 workers in medical services, administration, and support roles.[52] This sector benefits from institutions like the Medizinische Hochschule Brandenburg Theodor Fontane, established in 2014, which generates high-skilled jobs in education, research, and clinical training.[53] Manufacturing remains a key pillar, particularly in plastics and chemicals (over 2,000 district-wide employees, including firms like PAS Deutschland GmbH with 200 staff in Neuruppin) and metalworking (around 2,100 employees regionally, exemplified by ASL Automationssysteme Leske GmbH).[52] Food processing contributes significantly, with companies such as Dreistern-Konserven GmbH driving employment in canning and preservation.[52] Logistics and transport sectors leverage Neuruppin's proximity to Berlin and major highways like the A24, supporting around 1,200 jobs district-wide, while tourism—bolstered by the Ruppiner Seenland's lakes and cultural heritage—attracts about 1,850 workers in hospitality and related services.[52][53] Employment in commercial and industrial areas has grown by 6.4% since 2008, reflecting resilience in these sectors despite broader regional challenges post-reunification.[54] Overall, services (including healthcare and tourism) and manufacturing together account for the majority of jobs, with small and medium-sized enterprises dominating the landscape.[52]Post-reunification economic transitions and challenges

Following German reunification in 1990, Neuruppin faced acute economic disruptions typical of former East German towns, including the rapid privatization of state-owned enterprises under the Treuhandanstalt agency, which led to widespread factory closures and job losses in inefficient socialist-era industries such as manufacturing and agriculture.[55] The withdrawal of approximately 15,000 Soviet troops from local military installations by 1991 exacerbated these issues, eliminating ancillary employment in services, construction, and supply chains that had supported the garrison economy.[56] This triggered a sharp rise in unemployment, with rates in the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district—where Neuruppin serves as the administrative center—exceeding 15% during the 1990s, amid broader East German peaks averaging around 20% in Brandenburg by the early 2000s.[57] [58] Structural adjustment programs, supported by federal and state subsidies, facilitated a shift toward service-oriented sectors, including tourism leveraging Neuruppin's lakeside location and cultural heritage, as well as logistics and small-scale manufacturing.[56] [59] However, the transition was uneven, with many legacy firms failing to compete in a market economy, resulting in a persistently weak industrial base and reliance on public sector jobs.[60] Population outflow intensified these pressures, as younger workers migrated westward for opportunities, contributing to a demographic contraction from over 33,000 residents in 1993 to lower levels by the mid-2000s, further straining local tax revenues and infrastructure investment.[61] Persistent challenges included lower productivity compared to western Germany, limited innovation in high-value industries, and vulnerability to regional labor market fluctuations, with unemployment in the district remaining structurally higher than national averages into the 2010s despite gradual declines to around 6-7% by the 2020s.[62] Efforts to repurpose former military sites into commercial zones provided some relief, but overall convergence with western economic standards stalled after initial post-unity investments, highlighting causal factors like skill mismatches and infrastructural legacies from the GDR era.[63] [59]Recent developments and fiscal indicators

In 2024, employment subject to social security contributions in the Neuruppin labour market district (Ostprignitz-Ruppin) stood at 167,200, reflecting a decline of 0.8% from 168,500 in 2023.[64] Unemployment rose to 17,700 persons, up 2.3% from 17,300 in 2023, amid broader economic weakness in manufacturing and services.[64] By November 2024, the Neuruppin agency district reported 18,409 registered unemployed, a 0.4% increase from October, with the rate holding around 7-8% locally, exceeding Brandenburg's statewide 6.1%.[65] [66] Neuruppin's 2024 municipal budget recorded total revenues of €86.7 million against expenditures of €88.5 million, yielding a deficit of €1.9 million, financed without new borrowing and supported by cash reserves.[67] Investments totaled €8.5 million, concentrated in infrastructure such as roads (€725,000 for state roads, €881,000 for municipal streets) and parks (€1.1 million), alongside education and cultural facilities.[67] Debt service amounted to €1.1 million, prioritizing repayment amid persistent deficits in social services (e.g., kindergartens and libraries) offset by surpluses in utilities concessions (€1.0 million).[67] Key projects included €10 million in federal funding for Stadtwerke Neuruppin GmbH to advance energy and climate initiatives, alongside the "An der Pauline" residential development emphasizing climate adaptation and social housing.[68] [69] A December 2024 site study for Neuruppin West outlined economic development concepts to attract investors, addressing structural challenges like aging infrastructure despite constrained district finances.[70] [71]Government and Politics

Administrative structure and city council

Neuruppin operates as a große kreisangehörige Stadt within the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district of Brandenburg, with its administration centered on the Stadtverordnetenversammlung as the elected legislative body, a full-time mayor leading the executive branch, and appointed deputy mayors (Beigeordnete) overseeing specific departments. The city divides into 13 Ortsteile formed through the 1993 municipal reform, including both inhabited areas like Alt Ruppin, Buskow, Gnewikow, Gühlen-Glienicke, Karwe, Krangen, Lichtenberg, Molchow, Nietwerder, Radensdorf, and Wuthenow, as well as uninhabited nature conservation zones such as Neukammerluch and Redernluch; several Ortsteile maintain advisory local councils (Ortsbeiräte) elected to represent district-specific interests.[9][72] The Stadtverordnetenversammlung comprises 32 councilors elected every five years, with the mayor participating as a voting member; it approves budgets, ordinances, and policies while appointing committees for oversight. In the June 9, 2024, election—featuring 61.0% voter turnout among 26,585 eligible voters—the distribution of seats reflected diverse party and list strengths, as detailed below:| Party or List | Seats |

|---|---|

| AfD | 7 |

| CDU | 6 |

| SPD | 5 |

| Pro Ruppin | 4 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 3 |

| Die Linke | 3 |

| Wir in Neuruppin (WIN) | 2 |

| Wählergemeinschaft KBV | 1 |

| Einzelwahlliste Liefke | 1 |

Mayoral history and leadership transitions

Otto Theel, a member of the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), served as mayor of Neuruppin from 1994 to 2004, overseeing the town's administrative consolidation following the 1993 annexations of surrounding municipalities.[75] His tenure focused on economic stabilization in the post-reunification era, but it ended amid investigations into corruption allegations related to a hotel development project, where he facilitated a 70,000-euro loan for his son from an investor.[76] In 2008, Theel was convicted of corruption, receiving a nine-month suspended sentence, which highlighted governance vulnerabilities during the transition from East German structures.[77] Jens-Peter Golde succeeded Theel in 2005, holding office for 16 years until 2021 as an independent backed by the voter group Pro Ruppin, after leaving the SPD in 1993.[78] Golde's leadership emphasized city representation and development, earning support from parties including CDU and Greens for re-election bids, though his 2020 campaign faced threats, vehicle arson, and public scrutiny over alleged patronage networks reminiscent of prior scandals.[79] He lost a runoff election on November 29, 2020, to SPD candidate Nico Ruhle with 44.71% of the vote against Ruhle's 55.29%, marking a shift toward renewed party-affiliated leadership.[80] Nico Ruhle, a former judicial clerk and SPD city councilor since 2014, assumed the mayoral role on March 14, 2021, as Neuruppin's full-time representative and legal authority.[81] His election reflected voter priorities for stability amid ongoing post-reunification adaptations, with Ruhle prioritizing dialogue and administrative continuity in a town of over 50,000 residents.[82] No major transitions have occurred since, though mayoral terms in Brandenburg typically span eight years, subject to direct election.[83]Corruption cases and governance accountability