Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

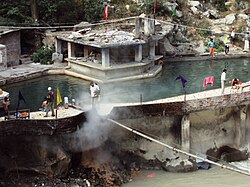

Mineral spring

View on Wikipedia

Mineral springs are naturally occurring springs that produce hard water, water that contains dissolved minerals. Salts, sulfur compounds, and gases are among the substances that can be dissolved in the spring water during its passage underground. In this they are unlike sweet springs, which produce soft water with no noticeable dissolved gasses. The dissolved minerals may alter the water's taste. Mineral water obtained from mineral springs, and the precipitated salts such as Epsom salt have long been important commercial products.

Some mineral springs may contain significant amounts of harmful dissolved minerals, such as arsenic, and should not be drunk.[1][2] Sulfur springs smell of rotten eggs due to hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which is hazardous and sometimes deadly. It is a gas, and it usually enters the body when it is breathed in.[3] The quantities ingested in drinking water are much lower and are not considered likely to cause harm, but few studies on long-term, low-level exposure have been done, as of 2003[update].[4]

The water of mineral springs is sometimes claimed to have therapeutic value. Mineral spas are resorts that have developed around mineral springs, where (often wealthy) patrons would repair to "take the waters" — meaning that they would drink (see hydrotherapy and water cure) or bathe in (see balneotherapy) the mineral water. Historical mineral springs were often outfitted with elaborate stone-works — including artificial pools, retaining walls, colonnades, and roofs — sometimes in the form of fanciful "Greek temples", gazebos, or pagodas. Others were entirely enclosed within spring houses.

Types

[edit]For many centuries, in Europe, North America, and elsewhere, commercial proponents of mineral springs classified them according to the chemical composition of the water produced and according to the medicinal benefits supposedly accruing from each:

- Arsenical springs contained arsenic

- Lithia Springs contained lithium salts.

- Chalybeate springs contained salts of iron.

- Alum springs contained alum.

- Sulfur springs contained hydrogen sulfide gas (see also fumeroles).

- Salt (saline) springs contained salts of calcium, magnesium or sodium.

- Alkaline springs contained an alkali.

- Calcic springs contained lime (calcium hydroxide).

- Thermal (hot) springs could contain a high concentration of various minerals.

- Soda springs contained carbon dioxide gas (soda water).

- Radioactive springs contain traces of radioactive substances such as radium or uranium.

Deposits

[edit]

Types of sedimentary rock – usually limestone (calcium carbonate) – are sometimes formed by the evaporation, or rapid precipitation, of minerals from spring water as it emerges, especially at the mouths of hot mineral springs. In cold mineral springs, the rapid precipitation of minerals results from the reduction of acidity when the CO2 gas bubbles out. (These mineral deposits can also be found in dried lakebeds.) Spectacular formations, including terraces, stalactites, stalagmites and 'frozen waterfalls' can result (see, for example, Mammoth Hot Springs).

One light-colored porous calcite of this type is known as travertine and has been used extensively in Italy and elsewhere as building material. Travertine can have a white, tan, or cream-colored appearance and often has a fibrous or concentric 'grain'.

Another type of spring water deposit, containing siliceous as well as calcareous minerals, is known as tufa. Tufa is similar to travertine but is even softer and more porous.

Chalybeate springs may deposit iron compounds such as limonite. Some such deposits were large enough to be mined as iron ore.

See also

[edit]- List of hot springs

- Sweet springs, those with no detectable sulfur or salt content

References

[edit]- ^ "Import Alert 29-02: Detention Without Physical Examination of Bottled Water due to Arsenic Due to Inorganic Arsenic". www.accessdata.fda.gov. FDA. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009.

- ^ "Bottled water brand with high levels of arsenic pulled from store shelves". NBC News.

- ^ "PUBLIC HEALTH STATEMENT: Hydrogen Sulfide" (PDF). DEPARTMENT of HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, Public Health ServiceAgency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, US Centers for Disease Control. December 2016.

- ^ "Hydrogen Sulfide in Drinking-water" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2003.

- Cohen, Stan (Revised 1981 edition), Springs of the Virginias: A Pictorial History, Charleston, West Virginia: Quarrier Press.

- LaMoreaux, Philip E.; Tanner, Judy T, eds. (2001), Springs and Bottled Water of the World: Ancient History, Source, Occurrence, Quality and use, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-61841-4, retrieved 13 July 2010

.jpg/250px-Wenceslas_Hollar_-_The_mineral_spring_(State_4).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Wenceslas_Hollar_-_The_mineral_spring_(State_4).jpg)