Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Diplomatic correspondence

View on Wikipedia

Diplomatic correspondence is correspondence between one state and another and is usually of a formal character. It follows several widely observed customs and styles in composition, substance, presentation, and delivery and can generally be categorized into letters and notes.

Letters

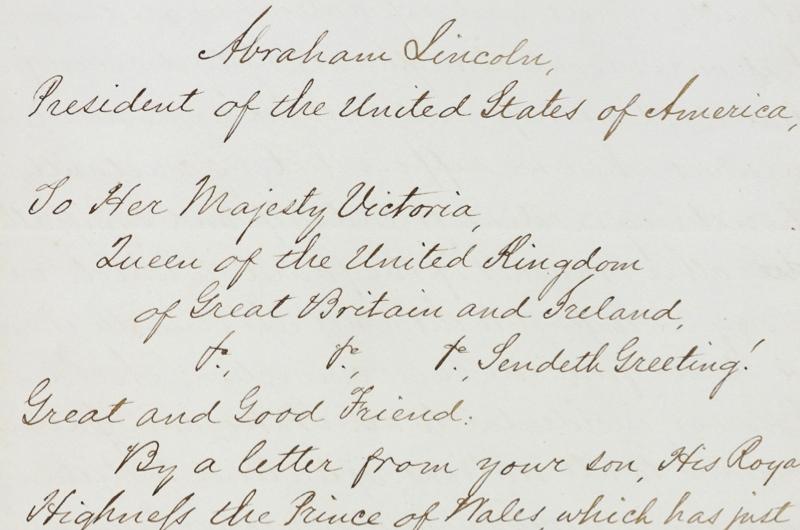

[edit]Letters are correspondence between heads of state, typically used for the appointment and recall of ambassadors; for the announcement of the death of a sovereign or an accession to the throne; or for expressions of congratulations or condolence.[1]

Letters between two monarchs of equal rank will typically begin with the salutation "Sir My Brother" (or "Madame My Sister", in the case of a female monarch) and close with the valediction "Your Good Brother" (or Sister, in the case of a female monarch). In the case where one monarch is of inferior rank to the other (for instance, if the Grand Duke of Luxembourg were to correspond with the King of the United Kingdom), the inferior monarch will use the salutation "Sire" (or "Madame"), while the superior monarch may refer to the other as "Cousin" instead of "Brother".[1] If either the sender or the recipient is the head-of-state of a republic, letters may begin with the salutation "My Great and Good Friend" and close with the valediction "Your Good Friend"; beneath the signature line will be inscribed "To Our Great and Good Friend [Name and Title of Recipient]".[1]

Letters of credence

[edit]

A letter of credence (lettres de créance) is the instrument by which a head of state appoints ("accredits") ambassadors to foreign countries.[2][3] Also known as credentials, the letter closes with a phrase "asking that credit may be given to all that the ambassador may say in the name of his sovereign or government."[2] The credentials are presented personally to the receiving country's head of state or viceroy in a formal ceremony. Letters of credence are worded carefully, as the sending or acceptance of a letter implies diplomatic recognition of the other government.[2] Letters of credence date to the thirteenth century.[4]

Letters of recall

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2023) |

A letter of recall is formal correspondence from one head-of-state notifying a second head-of-state that they are recalling their[clarification needed] state's ambassador.

Full powers

[edit]In cases where an envoy is entrusted with unusually extensive tasks that would not be covered by an ordinary permanent legation (such as the negotiation of a special treaty or convention, or representation at a diplomatic congress), an envoy may be given full powers (pleins pouvoirs) "in letters patent signed by the head of the State" designing "either limited or unlimited full powers, according to the requirements of the case."[3]

According to Satow's Diplomatic Practice, the bestowal of full powers traces its history to the Roman plena potestas; its purpose

was to be able to dispense, as far as possible, with the long delays needed in earlier times for referring problems back to higher authority. Their use at the present day is a formal recognition of the necessity of absolute confidence in the authority and standing of the negotiator.[1]

Notes

[edit]

Note verbale

[edit]A note verbale (French pronunciation: [nɔt vɛʁ.bal]) is a formal form of note and is so named by originally representing a formal record of information delivered orally. It is less formal than a note (also called a letter of protest) but more formal than an aide-mémoire. A note verbale can also be referred to as a third person note (TPN). Notes verbales are written in the third person and printed on official letterhead; they are typically sealed with an embosser or, in some cases, a stamp. All notes verbale begin with a formal salutation, typically:[1]

The [name of sending state's] Embassy presents its compliments to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and has the honor to invite their attention to the following matter.

Notes verbales will also close with a formal valediction, typically:[1]

The Embassy avails itself of this opportunity of assuring the Ministry of its highest consideration.

Notes verbales composed by the British Foreign Office are written on blue paper.[1]

Example

[edit]The Ukrainian protest of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation:[5]

The Ukrainian party categorically denies extension of sovereignty of the Russian Federation on Ukrainian territory, and reserves the right to exercise measures in accordance with international law and the laws of Ukraine.

Collective note

[edit]

A collective note is a letter delivered from multiple states to a single recipient state. It is always written in the third person.[6] The collective note has been a rarely used form of diplomatic communication due to the difficulty in obtaining agreements among multiple states to the exact wording of a letter.[7]

Identic note

[edit]An identic note is a letter delivered from a single state to multiple recipient states. Examples include the identic note sent by Thomas Jefferson regarding action against the Barbary Pirates and that from the United States to China and the Soviet Union in 1929. In the latter, the United States called on the other two powers to peacefully resolve their differences over the Eastern China Railway.[8]

Bouts de papier

[edit]A bout de papier (speaking note) may be presented by a visiting official when meeting with an official from another state at the conclusion of the meeting. Prepared in advance, it contains a short summary of the main points addressed by the visiting official during the meeting and, firstly, serves as a memory aid for the visiting official when speaking. Secondly, it removes ambiguity about the subject of the meeting occasioned by verbal miscues by the visiting official. Bouts de papier are always presented without credit or attribution so as to preserve the confidentiality of the meeting in case the document is later disclosed.[1]

Démarches and aides-mémoire

[edit]

A démarche (non-paper) is considered less formal than the already informal bout de papier. Officially described as "a request or intercession with a foreign official" it is a written request that is presented without attribution from the composing state and is, therefore, delivered in-person.[9]

Similar to a démarche, an aide-mémoire is a proposed agreement or negotiating text circulated informally among multiple states for discussion without committing the originating delegation's country to the contents. It has no identified source, title, or attribution and no standing in the relationship involved.

Protocol

[edit]

Standard diplomatic protocol varies from country to country, but generally requires clear yet concise translation between both parties.

Language

[edit]The earliest forms of diplomatic correspondence were, out of necessity, written in Latin, Latin being a common language among states of a linguistically diverse Europe. By the early 19th century, French had firmly supplanted Latin as the language of diplomacy; on one occasion, in 1817, the British attempted to correspond with the Austrian Imperial Court in English, prompting Klemens von Metternich to threaten retaliatory correspondence in Weanarisch. In modern times, English has largely replaced French as a diplomatic lingua franca in correspondence between two states lacking a common tongue.[10]

Rejection

[edit]States may sometimes reject diplomatic correspondence addressed to them by returning the original copy to the sending state. This is done as a rebuff of the contents of the correspondence and is typically reserved for cases where the receiving state feels the language used by the sending state is rude, or the subject matter represents an inappropriate intercession into the receiving state's internal affairs.[1]

Publication

[edit]Diplomatic correspondence has been published in the form of color books, such as the British Blue Books which go back to the seventeenth century, the German White Book and many others from World War I, partly for domestic consumption, and partly to cast blame on other sovereign actors.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roberts, Ivor (2009). Satow's Diplomatic Practice (6 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 45–66. ISBN 978-0199693559.

- ^ a b c Joanne Foakes, The Position of Heads of State and Senior Officials in International Law (Oxford University Press, 2014).

- ^ a b Lassa Oppenheim, International Law: A Treatise (Vol. 1, 2005: ed. Ronald Roxburgh), § 371, p. 550.

- ^ Pierre Chaplais, English Diplomatic Practice in the Middle Ages (Hambledon and London, 2003), p. 246.

- ^ МИД вызвал Временного поверенного в делах РФ в Украине для вручения ноты-протеста. unn.com.ua (in Russian). 18 March 2014.

- ^ Acquah-Dadzie, Kofi (1999). World Dictionary of Foreign Expressions: A Resource for Readers and Writers. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 273. ISBN 0865164231.

- ^ Lloyd (2012). The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Diplomacy. Springer. ISBN 978-1137017611.

- ^ Murty, Bhagevatula (1989). The International Law of Diplomacy: The Diplomatic Instrument and World Public Order. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 184. ISBN 0792300831.

- ^ Protocol for the Modern Diplomat (PDF). U.S. Department of State. 2013. p. 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-05.

- ^ Hamilton, Keith (2011). The Practice of Diplomacy: Its Evolution, Theory, and Administration. Taylor & Francis. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-0415497640.

- ^ Hartwig, Matthias (12 May 2014). "Colour books". In Bernhardt, Rudolf; Bindschedler, Rudolf; Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (eds.). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Vol. 9 International Relations and Legal Cooperation in General Diplomacy and Consular Relations. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 978-1-4832-5699-3. OCLC 769268852.