Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Open-design movement

View on Wikipedia

The open-design movement involves the development of physical products, machines and systems through use of publicly shared design information. This includes the making of both free and open-source software (FOSS) as well as open-source hardware. The process is generally facilitated by the Internet and often performed without monetary compensation. The goals and philosophy of the movement are identical to that of the open-source movement, but are implemented for the development of physical products rather than software.[9] Open design is a form of co-creation, where the final product is designed by the users, rather than an external stakeholder such as a private company.

History

[edit]Sharing of manufacturing information can be traced back to the 18th and 19th century.[10][11] Aggressive patenting put an end to that period of extensive knowledge sharing.[12] More recently, principles of open design have been related to the free and open-source software movements.[13] In 1997 Eric S. Raymond, Tim O'Reilly and Larry Augustin established "open source" as an alternative expression to "free software", and in 1997 Bruce Perens published The Open Source Definition. In late 1998, Dr. Sepehr Kiani (a PhD in mechanical engineering from MIT) realized that designers could benefit from open source policies, and in early 1999 he convinced Dr. Ryan Vallance and Dr. Samir Nayfeh of the potential benefits of open design in machine design applications.[14] Together they established the Open Design Foundation (ODF) as a non-profit corporation, and set out to develop an Open Design Definition.[14]

The idea of open design was taken up, either simultaneously or subsequently, by several other groups and individuals. The principles of open design are closely similar to those of open-source hardware design, which emerged in March 1998 when Reinoud Lamberts of the Delft University of Technology proposed on his "Open Design Circuits" website the creation of a hardware design community in the spirit of free software.[15]

Ronen Kadushin coined the title "Open Design" in his 2004 Master's thesis, and the term was later formalized in the 2010 Open Design Manifesto.[16]

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a significant test case for the open-design movement's principles of distributed manufacturing. With global supply chains struggling to meet the demand for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices, open design communities, such as Open Source Medical Supplies (OSCMS), contributed to fill the gap. It was documented that OSCMS producted over 48 million units of PPE and medical supplies by "citizen responders" and makerspaces across 86 countries.[17]

Current directions

[edit]The open-design movement currently unites two trends. On one hand, people apply their skills and time on projects for the common good, perhaps where funding or commercial interest is lacking, for developing countries or to help spread ecological or cheaper technologies. On the other hand, open design may provide a framework for developing advanced projects and technologies that might be beyond the resource of any single company or country and involve people who, without the copyleft mechanism, might not collaborate otherwise. There is now also a third trend, where these two methods come together to use high-tech open-source (e.g. 3D printing) but customized local solutions for sustainable development.[18] Open Design holds great potential in driving future innovation as recent research has proven that stakeholder users working together produce more innovative designs than designers consulting users through more traditional means.[19] The open-design movement may arguably organize production by prioritising socio-ecological well-being over corporate profits, over-production and excess consumption.[20]

Open machine design as compared to open-source software

[edit]The open-design movement is currently fairly nascent but holds great potential for the future. In some respects design and engineering are even more suited to open collaborative development than the increasingly common open-source software projects, because with 3D models and photographs the concept can often be understood visually. It is not even necessary that the project members speak the same languages to usefully collaborate.[citation needed]

However, there are certain barriers to overcome for open design when compared to software development where there are mature and widely used tools available and the duplication and distribution of code cost next to nothing. Creating, testing and modifying physical designs is not quite so straightforward because of the effort, time and cost required to create the physical artefact; although with access to emerging flexible computer-controlled manufacturing techniques the complexity and effort of construction can be significantly reduced (see tools mentioned in the fab lab article).

Organizations

[edit]

Open design was considered in 2012 a fledgling movement consisting of several unrelated or loosely related initiatives.[21] Many of these organizations are single, funded projects, while a few organizations are focusing on an area needing development. In some cases (e.g. Thingiverse for 3D printable designs or Appropedia for open source appropriate technology) organizations are making an effort to create a centralized open source design repository as this enables innovation.[22] Notable organizations include:

- AguaClara, an open-source engineering group at Cornell University publishing a design tool and CAD designs for water treatment plants

- Arduino, an open-source electronics hardware platform, community and company

- Elektor[23]

- Field Ready

- GrabCAD

- Instructables

- Local Motors (defunct): methods of transport, vehicles

- LittleBits[24]

- One Laptop Per Child (inactive), a project to provide children in developing territories laptop computers with open hardware and software

- OpenCores, digital electronic hardware

- Open Architecture Network

- Open Hardware and Design Alliance (OHANDA)

- OpenStructures (OSP),[25] a modular construction model where everyone designs on the basis of one shared geometrical grid.

- Open Source Ecology,[26] including solar cells[27]

- Thingiverse, miscellaneous

- VOICED

- VIA OpenBook netbook has CAD files for the design licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

- Wikispeed, open-source modular vehicles

- Open Source Design,[28] a community created in 2016 to hold space for designers interested in open source.

- Zoetrope, an open design low-cost wind turbine.[29][30]

See also

[edit]- 3D printing services

- Cosmopolitan localism

- Commons-based peer production

- Co-creation

- Knowledge commons

- Modular design

- OpenBTS

- Open manufacturing

- Open-source appropriate technology

- Open-source architecture

- Open Source Initiative

- Open-source software

- Open standard and Open standardization

- Open Design Alliance

- Digital public goods

References

[edit]- ^ "Design and implementation of 3D printer for Mechanical Engineering Courses". International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 9(3):293-312. March 2021. doi:10.31686/ijier.vol9.iss3.3001.

- ^ "Uzebox - The ATMega Game Console". Archived from the original on 2008-08-28.

- ^ "Evaluation + Tools + Best Practices: BugLabs and Open-Source Hardware Innovation". Worldchanging. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ "First Pics of Bug Labs Open-Source Hardware". TechCrunch. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ Sorrel, Charlie (2013-03-28). "Zoybar | Gadget Lab". Wired. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ "Ars Electronica Archiv - Award of Distinction 2012; The Free Universal Construction Kit; Shawn Sims, Golan Levin". Prix Ars Electronica. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Golan Levin, Shawn Sims. Free Universal Construction Kit. 2012". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ The Free Universal Construction Kit. Retrieved 28 July 2025 – via vimeo.com.

- ^ "Open collaborative design". AdCiv. 2010-07-29. Archived from the original on 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ Nuvolari, Alessandro 2004. Collective Invention during the British Industrial Revolution: The Case of the Cornish Pumping Engine. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 28, nr. 3: 347–363.

- ^ Allen, Robert C. 1983. Collective Invention. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 4, no. 1: 1–24.

- ^ Bessen, James E. and Nuvolari, Alessandro, Knowledge Sharing Among Inventors: Some Historical Perspectives (2012, forthcoming). In: Dietmar Harhoff and Karim Lakhani eds., Revolutionizing Innovation: Users, Communities and Open Innovation. Cambridge: MIT Press. Pre-Print: Boston Univ. School of Law, Law and Economics Research Paper No. 11-51; LEM Working Paper 2011/21. Available at http://www.bu.edu/law/faculty/scholarship/workingpapers/documents/BessenJ-NuvolariA101411fin.pdf Archived 2013-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vallance, Kiani and Nayfeh, Open Design of Manufacturing Equipment, CIRP 1st Int. Conference on Agile, 2001

- ^ a b R. Ryan Vallance, Bazaar Design of Nano and Micro Manufacturing Equipment, 2000

- ^ "Announcing: Open Design Circuits". Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ^ Alexander Vittouris, Mark Richardson. "Designing for Velomobile Diversity: Alternative opportunities for sustainable personal mobility" Archived 2012-09-16 at the Wayback Machine. 2012.

- ^ "DESIGN | MAKE | PROTECT". Open Source Medical Supplies. Retrieved 2025-12-13.

- ^ J. M Pearce, C. Morris Blair, K. J. Laciak, R. Andrews, A. Nosrat and I. Zelenika-Zovko, “3-D Printing of Open Source Appropriate Technologies for Self-Directed Sustainable Development”, Journal of Sustainable Development 3(4), pp. 17-29 (2010). [1]

- ^ Mitchell, Val; Ross, Tracy; Sims, Ruth; Parker, Christopher J. (2015). "Empirical investigation of the impact of using co-design methods when generating proposals for sustainable travel solutions". CoDesign. 12 (4): 205–220. doi:10.1080/15710882.2015.1091894.

- ^ Kostakis, Vasilis; Niaros, Vasilis; Giotitsas, Chris (2023-06-30). "Beyond global versus local: illuminating a cosmolocal framework for convivial technology development". Sustainability Science. 18 (5): 2309–2322. doi:10.1007/s11625-023-01378-1. ISSN 1937-0709.

- ^ Thomas J. Howard, Sofiane Achiche, Ali Özkil and Tim C. McAloone, Open Design And Crowdsourcing: Maturity, Methodology And Business Models, International Design Conference - Design 2012, Dubrovnik - Croatia, May 21–24, 2012.open access

- ^ Pearce J., Albritton S., Grant G., Steed G., & Zelenika I. 2012. A new model for enabling innovation in appropriate technology for sustainable development Archived 2012-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy 8(2) Published online Aug 20, 2012. open access Archived 2016-05-13 at the Portuguese Web Archive

- ^ "Elektor FAQ Elektor". Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "littleBits: DIY Electronics For Prototyping and Learning". Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Home". Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Open Source Ecology". Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Solar cells". Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Home". Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "The Zeotrope - A low-cost, open source wind turbine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23.

- ^ "Wind Turbine". Retrieved 16 April 2015.

External links

[edit]- Episodes of Collective Invention (Peter B. Meyer, August 2003) An article on several historical examples of what could be called "open design"

- "Lawrence Lessig and the Creative Commons Developing Nations License" (Alex Steffen, November 2006) An interview with Lawrence Lessig on the use of the Developing Nations License by Architecture for Humanity to create a global open design network

- "In the Next Industrial Revolution, Atoms Are the New Bits" (Chris Anderson, Wired February 2010)

Open-design movement

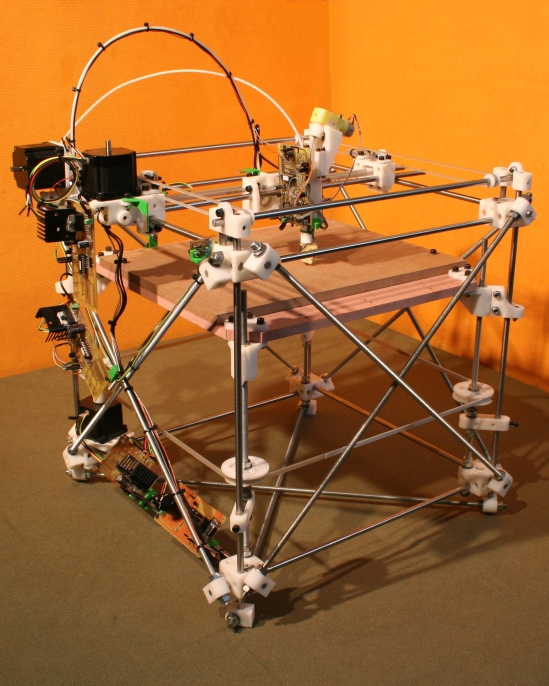

View on GrokipediaThe open-design movement refers to the collaborative development of physical products, machines, and systems through the public sharing of design files and information, permitting unrestricted access, modification, study, and redistribution, much like open-source software applied to tangible hardware.[1] Emerging in the late 1990s from the free and open-source software paradigm, it leverages digital tools such as CAD software and online repositories to facilitate peer-to-peer contributions, enabling distributed innovation and fabrication without proprietary barriers.[1] Key principles include transparency in design processes, use of standardized formats for easy modification, and licenses that ensure derived works remain open, as exemplified by the Open Source Hardware Association's criteria for documentation, component accessibility, and tool openness.[2] This approach contrasts with traditional closed design by prioritizing communal advancement over exclusive control, fostering rapid iteration through collective intelligence.[1] Notable achievements include the RepRap project, initiated in 2005 at the University of Bath, which developed low-cost, self-replicating 3D printers capable of producing most of their own parts, thereby catalyzing the global adoption of additive manufacturing and the maker community.[3] Other exemplars encompass Arduino microcontroller platforms for accessible electronics prototyping and Open Source Ecology's blueprint for modular machinery like tractors, demonstrating scalable applications in agriculture and beyond.[1] While open-design has democratized technology access and lowered entry barriers—evident in cost reductions for solar photovoltaic designs and widespread hardware hacking—challenges persist, including intellectual property tensions where commercial entities may exploit shared designs without reciprocal contributions, and difficulties in maintaining quality or safety standards absent centralized oversight.[1] These issues highlight hardware's inherent physical constraints compared to software's fluidity, yet the movement's causal impact lies in shifting manufacturing toward user-driven, resilient ecosystems resilient to supply chain disruptions.[1]

Definition and Principles

Core Concepts and Motivations

The open-design movement applies open-source principles to the development of physical products, machines, and systems by publicly sharing comprehensive design documentation, such as CAD files, schematics, bill of materials, and assembly instructions, under licenses that permit study, modification, reproduction, and distribution.[2] This approach emphasizes transparency and reproducibility, enabling users to verify functionality, customize designs, and manufacture hardware independently, distinct from proprietary models that restrict access to intellectual property.[4] Core to the movement is the provision of "source" information sufficient for exact replication, fostering collaborative improvement akin to software but adapted to tangible artifacts' physical constraints.[2] Motivations for participation stem from both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsically, contributors are driven by altruism to democratize technology access, particularly for underserved communities, and by personal enjoyment in community reciprocity and recognition.[4] Extrinsically, open designs reduce research and development costs, accelerate time-to-market through user contributions, and align with market demands for customizable, repairable products.[4] Pioneering efforts, such as Adrian Bowyer's 2005 RepRap project, exemplify these drives by aiming to create self-replicating 3D printers for universal manufacturing access, embedding open-source principles to enable rapid proliferation and economic benefits like household savings of $300–$2,000 annually via on-demand production.[5] These concepts and motivations challenge traditional intellectual property reliance, promoting innovation through collective effort while addressing barriers like manufacturing scalability and legal enforceability of hardware licenses.[4]Distinctions from Proprietary and Closed Design

The open-design movement fundamentally differs from proprietary and closed design in the public accessibility of complete technical documentation, including schematics, bill of materials, and fabrication instructions, which allows independent verification, replication, and enhancement without reliance on the original creator.[6] In proprietary systems, such details are deliberately obscured or restricted, often enforced through trade secrets, patents, and non-disclosure agreements to safeguard competitive edges and prevent unauthorized replication.[7] This opacity in closed design necessitates reverse engineering for modifications, a process that is legally hazardous and technically inefficient compared to the transparent repositories typical of open design.[8] Licensing frameworks further delineate the approaches: open design employs permissive or copyleft licenses, such as those modeled on open-source software but adapted for hardware (e.g., the CERN Open Hardware Licence released in 2011), granting rights to modify, distribute, and commercialize derivatives under specified conditions that preserve openness.[9] Proprietary designs, conversely, utilize restrictive intellectual property regimes—encompassing copyrights on documentation, patents on inventions (with global filings averaging over 3 million annually as of 2023 per WIPO data), and end-user license agreements—that prohibit or monetize alterations, thereby centralizing control and innovation within originating entities. These mechanisms in closed systems prioritize return on R&D investment through exclusivity, whereas open design shifts value capture toward services, customization, or ecosystem effects rather than design monopolies.[8] A hardware-specific barrier amplifies these distinctions: unlike software's low marginal reproduction cost, open design's physical outputs demand fabrication resources, enabling distributed manufacturing but exposing designs to imperfect replication risks absent in controlled proprietary production lines.[9] Closed designs mitigate such variances through standardized, proprietary supply chains, though this can entrench vendor lock-in and hinder interoperability. Empirical analyses indicate open approaches accelerate iterative improvements via diverse contributors—evident in projects like RepRap 3D printers, where community forks have yielded over 100 variants since 2005—but require robust documentation to overcome fabrication tolerances not inherent in digital-only closed-source models.[8][6]Historical Development

Precursors and Early Influences

The free software movement, originating with Richard Stallman's 1983 announcement of the GNU Project, provided a foundational ideology for open design by emphasizing collaborative development, transparency, and the right to modify and redistribute knowledge, principles later extended from software to tangible hardware.[1] This influence stemmed from the demonstrated efficacy of shared code in accelerating innovation, as seen in the Linux kernel's growth from 1991 onward, prompting hardware enthusiasts to question proprietary barriers in physical design.[1] Hardware-specific precursors emerged in mid-20th-century hobbyist communities, where engineers and amateurs routinely shared circuit schematics and build instructions via magazines and clubs, fostering iterative improvements without formal licensing. The Homebrew Computer Club, established on March 5, 1975, in California's Silicon Valley, epitomized this ethos; members like Steve Wozniak exchanged designs for early microcomputers, including Altair 8800 expansions, enabling rapid prototyping and the birth of personal computing firms such as Apple.[10] Analogous practices prevailed in the amateur radio sector, where operators published detailed hardware blueprints in journals like QST since 1915, prioritizing collective problem-solving over exclusivity.[10] By the late 1990s, these traditions converged with software openness to formalize open hardware advocacy. In 1997, Bruce Perens, a key figure in the Open Source Initiative, initiated the Open Hardware Certification Program and trademarked "open hardware" to certify designs permitting unrestricted study, modification, and distribution.[10] The following year saw David Freeman's Open Hardware Specification Project (OHSpec) and Reinoud Lamberts' Open Design Circuits, both aiming to standardize shareable hardware documentation. In 1999, Sepehr Kiani, Ryan Vallance, and Samir Nayfeh founded the Open Design Foundation, drafting the first Open Design Definition to mirror software freedoms for mechanical and electronic systems.[10] These efforts addressed hardware's unique challenges, such as fabrication costs, while building on empirical successes from software collaboration.[1]Emergence and Key Milestones (2000s Onward)

The open-design movement emerged prominently in the mid-2000s, extending open-source principles from software to tangible hardware and products through publicly shared schematics, blueprints, and fabrication instructions. This shift was facilitated by advancements in digital fabrication tools like 3D printing and microcontroller boards, enabling collaborative development outside traditional proprietary models.[10] A foundational milestone was the initiation of the RepRap project on May 29, 2005, by Adrian Bowyer, a senior lecturer in mechanical engineering at the University of Bath, with the objective of developing a self-replicating 3D printer that users could largely fabricate from open designs to promote universal access to manufacturing capabilities.[11] The project emphasized designs printable with 50-60% of parts produced by the machine itself, fostering a distributed production model and inspiring subsequent iterations like the Darwin printer released in 2008.[12] Concurrently, the Arduino project launched in 2005 at the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea in Italy by founders including Massimo Banzi, David Cuartielles, and Tom Igoe, introducing an open-source electronics platform with freely available hardware schematics and software IDE to simplify prototyping for artists, designers, and hobbyists. By providing microcontroller boards under creative commons licenses, Arduino accelerated adoption, with millions of units produced by community efforts and third-party manufacturers by the late 2000s.[13] Formalization efforts intensified in 2007 with the release of the TAPR Open Hardware License by the Tucson Amateur Packet Radio group, the first license tailored for hardware sharing that permitted modification and distribution while requiring attribution and open derivative works.[10] That year also saw the founding of the Open Hardware Foundation by Patrick McNamara to support projects like the Open Graphics Project, aiming to certify and promote open hardware standards.[10] The movement's institutional growth accelerated in 2010 with the inaugural Open Hardware Summit in New York City on September 23, organized by Alicia Gibb and Ayah Bdeir, drawing 320 participants to discuss definitions, licensing, and business models for open hardware.[10] This event preceded the July 2010 release of Open Source Hardware Definition version 0.3 and culminated in version 1.0 adoption on February 10, 2011, establishing criteria for documentation availability, permission to make/modify/sell, and non-paywalled access to designs.[14] In 2012, the Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA) was established as a nonprofit to steward the definition, certify compliant projects via unique identifiers, and host annual summits, solidifying organizational infrastructure for the burgeoning community.[15] These developments marked the transition from ad-hoc projects to a structured ecosystem, influencing fields from consumer electronics to scientific instrumentation.[10]Methodologies and Technical Practices

Design Documentation Requirements

Effective open-design documentation must enable independent replication, modification, and distribution of the design by third parties, distinguishing it from proprietary practices where details are obscured to protect intellectual property. According to the Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA), core requirements include releasing hardware with comprehensive documentation such as design files that permit alterations and redistribution.[2] This ensures designs are not merely descriptive but functionally reproducible, addressing barriers like incomplete specifications that hinder collaborative improvement. Key elements typically encompass:- Design files: Machine-readable formats like CAD models (e.g., STEP, STL for 3D printing), schematics, and PCB layouts, released under permissive licenses to facilitate editing. OSHWA mandates these files be modifiable, excluding those locked in proprietary software without export options.[16]

- Bill of Materials (BOM): Detailed lists of components, including part numbers, suppliers, quantities, and costs, to allow sourcing without reverse engineering. In projects like RepRap, BOMs specify off-the-shelf parts for printers, enabling global replication.[17]

- Assembly and manufacturing instructions: Step-by-step guides with diagrams, tolerances, and tools required, often including firmware or software source code. RepRap's full documentation standard requires all CAD files, photos, electronics schematics, and firmware to be publicly hosted for verification and iteration.[18]

- Testing and validation data: Performance metrics, failure modes, and calibration procedures to verify builds against originals, promoting reliability in decentralized production.