Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ozone layer

View on Wikipedia

The ozone layer or ozone shield is a region of Earth's stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. It contains a high concentration of ozone (O3) in relation to other parts of the atmosphere, although still small in relation to other gases in the stratosphere. The ozone layer peaks at 8 to 15 parts per million of ozone,[1] while the average ozone concentration in Earth's atmosphere as a whole is about 0.3 parts per million. The ozone layer is mainly found in the lower portion of the stratosphere, from approximately 15 to 35 kilometers (9 to 22 mi) above Earth, although its thickness varies seasonally and geographically.[2]

The ozone layer was discovered in 1913 by French physicists Charles Fabry and Henri Buisson. Measurements of the sun showed that the radiation sent out from its surface and reaching the ground on Earth is usually consistent with the spectrum of a black body with a temperature in the range of 5,500–6,000 K (5,230–5,730 °C), except that there was no radiation below a wavelength of about 310 nm at the ultraviolet end of the spectrum. It was deduced that the missing radiation was being absorbed by something in the atmosphere. Eventually the spectrum of the missing radiation was matched to only one known chemical, ozone.[3] Its properties were explored in detail by the British meteorologist G. M. B. Dobson, who developed a simple spectrophotometer (the Dobsonmeter) that could be used to measure stratospheric ozone from the ground. Between 1928 and 1958, Dobson established a worldwide network of ozone monitoring stations, which continue to operate to this day. The "Dobson unit" (DU), a convenient measure of the amount of ozone overhead, is named in his honor.

The ozone layer absorbs 97 to 99 percent of the Sun's medium-frequency ultraviolet light (from about 200 nm to 315 nm wavelength), which otherwise would potentially damage exposed life forms near the surface.[4]

In 1985, atmospheric research revealed that the ozone layer was being depleted by chemicals released by industry, mainly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Concerns that increased UV radiation due to ozone depletion threatened life on Earth, including increased skin cancer in humans and other ecological problems,[5] led to bans on the chemicals, and the latest evidence is that ozone depletion has slowed or stopped. The United Nations General Assembly has designated September 16 as the International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer.

Venus also has a thin ozone layer at an altitude of 100 kilometers above the planet's surface.[6]

Sources

[edit]

The Earth's ozone layer formed about 500 million years ago, when the neoproterozoic oxygenation event brought the fraction of oxygen in the atmosphere to about 20%.[7]

The photochemical mechanisms that give rise to the ozone layer were discovered by the British physicist Sydney Chapman in 1930. Ozone in the Earth's stratosphere is created by ultraviolet light striking ordinary oxygen molecules containing two oxygen atoms (O2), splitting them into individual oxygen atoms (atomic oxygen); the atomic oxygen then combines with unbroken O2 to create ozone, O3. The ozone molecule is unstable (although, in the stratosphere, long-lived) and when ultraviolet light hits ozone it splits into a molecule of O2 and an individual atom of oxygen, a continuing process called the ozone–oxygen cycle. Chemically, this can be described as:

About 90% of the ozone in the atmosphere is contained in the stratosphere. Ozone concentrations are greatest between about 20 and 40 kilometres (66,000 and 131,000 ft), where they range from about 2 to 8 parts per million. If all of the ozone were compressed to the pressure of the air at sea level, it would be only 3 millimetres (1⁄8 inch) thick.[8]

Ultraviolet light

[edit]

Although the concentration of the ozone in the ozone layer is very small, it is vitally important to life because it absorbs biologically harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation coming from the Sun. Extremely short or vacuum UV (10–100 nm) is screened out by nitrogen. UV radiation capable of penetrating nitrogen is divided into three categories, based on its wavelength; these are referred to as UV-A (400–315 nm), UV-B (315–280 nm), and UV-C (280–100 nm).

UV-C, which is very harmful to all living things, is entirely screened out by a combination of dioxygen (< 200 nm) and ozone (> about 200 nm) by around 35 kilometres (115,000 ft) altitude. UV-B radiation can be harmful to the skin and is the main cause of sunburn; excessive exposure can also cause cataracts, immune system suppression, and genetic damage, resulting in problems such as skin cancer. The ozone layer (which absorbs from about 200 nm to 310 nm with a maximal absorption at about 250 nm)[9] is very effective at screening out UV-B; for radiation with a wavelength of 290 nm, the intensity at the top of the atmosphere is 350 million times stronger than at the Earth's surface. Nevertheless, some UV-B, particularly at its longest wavelengths, reaches the surface, and is important for the skin's production of vitamin D in mammals.

Ozone is transparent to most UV-A, so most of this longer-wavelength UV radiation reaches the surface, and it constitutes most of the UV reaching the Earth. This type of UV radiation is significantly less harmful to DNA, although it may still potentially cause physical damage, premature aging of the skin, indirect genetic damage, and skin cancer.[10]

Distribution in the stratosphere

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

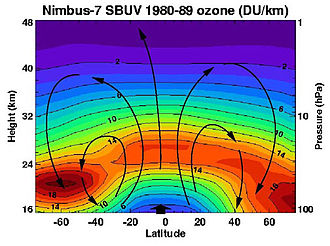

The thickness of the ozone layer varies worldwide and is generally thinner near the equator and thicker near the poles.[11] Thickness refers to how much ozone is in a column over a given area and varies from season to season. The reasons for these variations are due to atmospheric circulation patterns and solar intensity.[12]

The ozone layer ends gradually, but in general its upper limit is where air becomes too thin for UV light to generate much ozone, and its lower limit is where generated ozone blocks enough UV light to stop most ozone production.

In the homosphere, wind-driven movement is more important than relative gas weight. The majority of ozone is produced over the tropics and is transported toward the poles by stratospheric wind patterns. In the northern hemisphere these patterns, known as the Brewer–Dobson circulation, make the ozone layer thickest in the spring and thinnest in the fall.[11] When ozone is produced by solar UV radiation in the tropics, it is done so by circulation lifting ozone-poor air out of the troposphere and into the stratosphere where the sun photolyzes oxygen molecules and turns them into ozone. Then, the ozone-rich air is carried to higher latitudes and drops into lower layers of the atmosphere.[11]

Research has found that the ozone levels in the United States are highest in the spring months of April and May and lowest in October. While the total amount of ozone increases moving from the tropics to higher latitudes, the concentrations are greater in high northern latitudes than in high southern latitudes, with spring ozone columns in high northern latitudes occasionally exceeding 600 DU and averaging 450 DU whereas 400 DU constituted a usual maximum in the Antarctic before anthropogenic ozone depletion. This difference occurred naturally because of the weaker polar vortex and stronger Brewer–Dobson circulation in the northern hemisphere owing to that hemisphere's large mountain ranges and greater contrasts between land and ocean temperatures.[13] The difference between high northern and southern latitudes has increased since the 1970s due to the ozone hole phenomenon.[11] The highest amounts of ozone are found over the Arctic during the spring months of March and April, but the Antarctic has the lowest amounts of ozone during the summer months of September and October,

Depletion

[edit]

The ozone layer can be depleted by free radical catalysts, including nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydroxyl (OH), atomic chlorine (Cl), and atomic bromine (Br). While there are natural sources for all of these species, the concentrations of chlorine and bromine increased markedly in recent decades because of the release of large quantities of man-made organohalogen compounds, especially chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and bromofluorocarbons.[14] Atmospheric components are not sorted out by weight in the homosphere because of wind-driven mixing that extends to an altitude of about 90 km, well above the ozone layer. So despite being heavier than diatomic nitrogen and oxygen, these highly stable compounds rise into the stratosphere, where Cl and Br radicals are liberated by the action of ultraviolet light. Each radical is then free to initiate and catalyze a chain reaction capable of breaking down over 100,000 ozone molecules. By 2009, nitrous oxide was the largest ozone-depleting substance (ODS) emitted through human activities.[15]

The breakdown of ozone in the stratosphere results in reduced absorption of ultraviolet radiation. Consequently, unabsorbed and dangerous ultraviolet radiation reaches the Earth's surface at a higher intensity. Ozone levels have dropped by a worldwide average of about 4 percent since the late 1970s. For approximately 5 percent of the Earth's surface, around the north and south poles, much larger seasonal declines have been seen, and are described as "ozone holes". "Ozone holes" are actually patches in the ozone layer in which the ozone is thinner. The thinnest parts of the ozone are at the polar points of Earth's axis.[16] The discovery of the annual depletion of ozone above the Antarctic was first announced by Joe Farman, Brian Gardiner, and Jonathan Shanklin, in a paper which appeared in Nature on May 16, 1985.

Regulation attempts have included but not have been limited to the Clean Air Act implemented by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. The Clean Air Act introduced the requirement of National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) with ozone pollutions being one of six criteria pollutants. This regulation has proven to be effective since counties, cities, and tribal regions must abide by these standards and the EPA also provides assistance for each region to regulate contaminants.[17] Effective presentation of information has also proven to be important in order to educate the general population of the existence and regulation of ozone depletion and contaminants. A scientific paper was written by Sheldon Ungar in which the author explores and studies how information about the depletion of the ozone, climate change, and various related topics. The ozone case was communicated to lay persons "with easy-to-understand bridging metaphors derived from the popular culture" and related to "immediate risks with everyday relevance".[18] The specific metaphors used in the discussion (ozone shield, ozone hole) proved quite useful and, compared to global climate change, the ozone case was much more seen as a "hot issue" and imminent risk. Lay people were cautious about a depletion of the ozone layer and the risks of skin cancer.

Satellites burning up upon re-entry into Earth's atmosphere produce aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles that endure in the atmosphere for decades.[19] Estimates for 2022 alone were ~17 metric tons (~30 kg of nanoparticles per ~250 kg satellite).[19] Increasing populations of satellite constellations can eventually lead to significant ozone depletion.[19]

"Bad" ozone[clarification needed] can cause adverse health risks respiratory effects (difficulty breathing) and is proven to be an aggravator of respiratory illnesses such as asthma, COPD, and emphysema.[20] That is why many countries have set in place regulations to improve "good" ozone[clarification needed] and prevent the increase of "bad" ozone in urban or residential areas. In terms of ozone protection (the preservation of "good" ozone) the European Union has strict guidelines on what products are allowed to be bought, distributed, or used in specific areas.[21] With effective regulation, the ozone is expected to heal over time.[22]

In 1978, the United States, Canada, and Norway enacted bans on CFC-containing aerosol sprays that damage the ozone layer but the European Community rejected a similar proposal. In the U.S., chlorofluorocarbons continued to be used in other applications, such as refrigeration and industrial cleaning, until after the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole in 1985. After negotiation of an international treaty (the Montreal Protocol), CFC production was capped at 1986 levels with commitments to long-term reductions.[23] This allowed for a ten-year phase-in for developing countries[24] (identified in Article 5 of the protocol). Since then, the treaty was amended to ban CFC production after 1995 in developed countries, and later in developing countries.[25] All of the world's 197 countries have signed the treaty. Beginning January 1, 1996, only recycled or stockpiled CFCs were available for use in developed countries like the US. The production phaseout was possible because of efforts to ensure that there would be substitute chemicals and technologies for all ODS uses.[26]

On August 2, 2003, scientists announced that the global depletion of the ozone layer might be slowing because of the international regulation of ozone-depleting substances. In a study organized by the American Geophysical Union, three satellites and three ground stations confirmed that the upper-atmosphere ozone-depletion rate slowed significantly over the previous decade. Some breakdown was expected to continue because of ODSs used by nations which have not banned them, and because of gases already in the stratosphere. Some ODSs, including CFCs, have very long atmospheric lifetimes ranging from 50 to over 100 years. It has been estimated that the ozone layer will recover to 1980 levels near the middle of the 21st century.[27] A gradual trend toward "healing" was reported in 2016.[28]

Compounds containing C–H bonds (such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons, or HCFCs) have been designed to replace CFCs in certain applications. These replacement compounds are more reactive and less likely to survive long enough in the atmosphere to reach the stratosphere where they could affect the ozone layer. While being less damaging than CFCs, HCFCs can have a negative impact on the ozone layer, so they are also being phased out.[29] These in turn are being replaced by hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and other compounds that do not destroy stratospheric ozone at all.

The residual effects of CFCs accumulating within the atmosphere lead to a concentration gradient between the atmosphere and the ocean. This organohalogen compound dissolves into the ocean's surface waters and acts as a time-dependent tracer. This tracer helps scientists study ocean circulation by tracing biological, physical, and chemical pathways.[30]

Implications for astronomy

[edit]As ozone in the atmosphere prevents most energetic ultraviolet radiation reaching the surface of the Earth, astronomical data in these wavelengths have to be gathered from satellites orbiting above the atmosphere and ozone layer. Most of the light from young hot stars is in the ultraviolet and so study of these wavelengths is important for studying the origins of galaxies. The Galaxy Evolution Explorer, GALEX, is an orbiting ultraviolet space telescope launched on April 28, 2003, which operated until early 2012.[31]

-

This GALEX image of the Cygnus Loop nebula could not have been taken from the surface of the Earth because the ozone layer blocks the ultra-violet radiation emitted by the nebula.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ NASA Ozone Watch: Ozone facts

- ^ "Ozone Basics". NOAA. March 20, 2008. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ McElroy, C.T.; Fogal, P.F. (2008). "Ozone: From discovery to protection". Atmosphere-Ocean. 46 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:2008AtO....46....1M. doi:10.3137/ao.460101. S2CID 128994884.

- ^ "Ozone layer". Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ An Interview with Lee Thomas, EPA's 6th Administrator. Video, Transcript (see p13). April 19, 2012.

- ^ SPACE.com staff (October 11, 2011). "Scientists discover Ozone Layer on Venus". SPACE.com. Purch. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ Paul M. Sutter (July 20, 2023). "How the Ozone Layer Evolved and Why It's Important". Discover Magazine.

- ^ "NASA Facts Archive". Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Matsumi, Y.; Kawasaki, M. (2003). "Photolysis of Atmospheric Ozone in the Ultraviolet Region" (PDF). Chem. Rev. 103 (12): 4767–4781. doi:10.1021/cr0205255. PMID 14664632. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Narayanan, D.L.; Saladi, R.N.; Fox, J.L. (2010). "Review: Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer". International Journal of Dermatology. 49 (9): 978–986. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04474.x. PMID 20883261. S2CID 22224492.

- ^ a b c d Tabin, Shagoon (2008). Global Warming: The Effect Of Ozone Depletion. APH Publishing. p. 194. ISBN 9788131303962. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Nasa Ozone Watch: Ozone facts". ozonewatch.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Douglass, Anne R.; Newman, Paul A.; Solomon, Susan (2014). "The Antarctic ozone hole: An update". Physics Today. 67 (7). American Institute of Physics: 42–48. Bibcode:2014PhT....67g..42D. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2449. hdl:1721.1/99159.

- ^ "Halocarbons and Other Gases". Emissions of Greenhouse Gases in the United States 1996. Energy Information Administration. 1997. Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ "NOAA Study Shows Nitrous Oxide Now Top Ozone-Depleting Emission". NOAA. August 27, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ "ozone layer | National Geographic Society". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (December 14, 2016). "Ozone Implementation Regulatory Actions". epa.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Ungar, Sheldon (July 2000). "Knowledge, ignorance and the popular culture: climate change versus the ozone hole". Public Understanding of Science. 9 (3): 297–312. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/306. ISSN 0963-6625. S2CID 7089937.

- ^ a b c Ferreira, Jose P.; Huang, Ziyu; Nomura, Ken-ichi; Wang, Joseph (June 11, 2024). "Potential Ozone Depletion From Satellite Demise During Atmospheric Reentry in the Era of Mega-Constellations". Geophysical Research Letters. 51 (11). Bibcode:2024GeoRL..5109280F. doi:10.1029/2024GL109280.

- ^ Zhang, Junfeng (Jim); Wei, Yongjie; Fang, Zhangfu (2019). "Ozone Pollution: A Major Health Hazard Worldwide". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 2518. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02518. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 6834528. PMID 31736954.

- ^ "Ozone Regulation". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (July 15, 2015). "International Treaties and Cooperation about the Protection of the Stratospheric Ozone Layer". epa.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Morrisette, Peter M. (1989). "The Evolution of Policy Responses to Stratospheric Ozone Depletion". Natural Resources Journal. 29: 793–820. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ An Interview with Lee Thomas, EPA's 6th Administrator. Video, Transcript (see p15). April 19, 2012.

- ^ "Amendments to the Montreal Protocol". EPA. August 19, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ "Brief Questions and Answers on Ozone Depletion". EPA. June 28, 2006. Archived from the original on April 18, 1997. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ "Stratospheric Ozone and Surface Ultraviolet Radiation" (PDF). Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2010. WMO. 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Solomon, Susan, et al. (June 30, 2016). "Emergence of healing in the Antarctic ozone layer". Science. 353 (6296): 269–74. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..269S. doi:10.1126/science.aae0061. hdl:1721.1/107197. PMID 27365314.

- ^ "Ozone Depletion Glossary". EPA. Archived from the original on April 18, 1997. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ Fine, Rana A. (2011). "Observations of CFCs and SF6 as Ocean Tracers" (PDF). Annual Review of Marine Science. 3: 173–95. Bibcode:2011ARMS....3..173F. doi:10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163933. PMID 21329203. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 10, 2015.

- ^ "ozone layer". National Geographic Society. May 9, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Science

- Andersen, S. O. (2015). "Lessons from the stratospheric ozone layer protection for climate". Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. 5 (2): 143–162. Bibcode:2015JEnSS...5..143A. doi:10.1007/s13412-014-0213-9. S2CID 129725437.

- Andersen, S.O.; Sarma, K.M.; Sinclair, L. (2012). Protecting the Ozone Layer: The United Nations History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-84977-226-6.

- Ritchie, Hannah, "What We Learned from Acid Rain: By working together, the nations of the world can solve climate change", Scientific American, vol. 330, no. 1 (January 2024), pp. 75–76. "[C]ountries will act only if they know others are willing to do the same. With acid rain, they did act collectively.... We did something similar to restore Earth's protective ozone layer.... [T]he cost of technology really matters.... In the past decade the price of solar energy has fallen by more than 90 percent and that of wind energy by more than 70 percent. Battery costs have tumbled by 98 percent since 1990, bringing the price of electric cars down with them....[T]he stance of elected officials matters more than their party affiliation.... Change can happen – but not on its own. We need to drive it." (p. 76.)

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010). Environmental Effects of Ozone Depletion and its Interactions with Climate Change: 2010 Assessment. Nairobi: UNEP.

- Velders, G. J. M.; Fahey, D. W.; Daniel, J. S.; McFarland, M.; Andersen, S. O. (2009). "The large contribution of projected HFC emissions to future climate forcing". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (27): 10949–10954. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610949V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902817106. PMC 2700150. PMID 19549868. S2CID 3743609.

- Velders, Guus J.M.; Andersen, Stephen O.; Daniel, John S.; Fahey, David W.; McFarland, Mack (2007). "The Importance of the Montreal Protocol in Protecting Climate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (12): 4814–4819. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.4814V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610328104. PMC 1817831. PMID 17360370.

- Policy

- Zaelke, Durwood; Borgford-Parnell, Nathan (2015). "The importance of phasing down hydrofluorocarbons and other short-lived climate pollutants". Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. 5 (2): 169–175. Bibcode:2015JEnSS...5..169Z. doi:10.1007/s13412-014-0215-7. S2CID 128974741.

- Xu, Y.; Zaelke, D.; Velders, G. J. M.; Ramanathan, V. (2013). "The role of HFCS in mitigating 21st century climate change". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 13 (12): 6083–6089. Bibcode:2013ACP....13.6083X. doi:10.5194/acp-13-6083-2013.

- Molina, M.; Zaelke, D.; Sarma, K. M.; Andersen, S. O.; Ramanathan, V.; Kaniaru, D. (2009). "Reducing abrupt climate change risk using the Montreal Protocol and other regulatory actions to complement cuts in CO2 emissions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (49): 20616–20621. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902568106. PMC 2791591. PMID 19822751. S2CID 13240115.

- Anderson, S. O.; Sarma, M. K.; Taddonio, K. (2007). Technology Transfer for the Ozone Layer: Lessons for Climate Change. London: Earthscan. ISBN 9781849772846.

- Benedick, Richard Elliot; World Wildlife Fund (U.S.); Institute for the Study of Diplomacy. Georgetown University. (1998). Ozone Diplomacy: New Directions in Safeguarding the Planet (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-65003-9. (Ambassador Benedick was the Chief U.S. Negotiator at the meetings that resulted in the Montreal Protocol.)

- Chasek, P. S.; Downie, David L.; Brown, J. W. (2013). Global Environmental Politics (6th ed.). Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813348971.

- Grundmann, Reiner (2001). Transnational Environmental Policy: Reconstructing Ozone. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-22423-9.

- Parson, E. (2003). Protecting the Ozone Layer: Science and Strategy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190288716.

External links

[edit]- Stratospheric ozone: an electronic textbook

- Ozone Layer Info (archived July 2, 2004)

- The CAMS stratospheric ozone service delivers maps, datasets, and validation reports about the past and current state of the ozone layer.

Ozone layer

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Location

The ozone layer is a region of elevated ozone (O₃) concentration within Earth's stratosphere, comprising approximately 90% of the planet's total atmospheric ozone and functioning primarily to absorb incoming solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation in the biologically harmful UVB and UVC wavelengths.[10] [11] This layer is not a uniform sheet but a dynamically varying zone where ozone molecules, formed through photochemical reactions involving oxygen (O₂) and UV light, reach partial pressures of up to several millibars, far exceeding tropospheric levels.[12] [1] It resides predominantly in the lower stratosphere, spanning altitudes of roughly 15 to 35 kilometers (9 to 22 miles) above sea level, with peak concentrations typically occurring between 20 and 30 kilometers depending on latitude and solar conditions.[12] [11] [13] The underlying stratosphere itself extends from about 10 to 50 kilometers, bounded below by the tropopause (varying from 8-18 kilometers by latitude) and above by the stratopause, but the ozone maximum aligns with the layer's temperature inversion and low water vapor content, which stabilize O₃ against rapid decomposition.[10] [1] Global measurements, such as those from satellite instruments like TOMS and OMI, confirm this vertical distribution, with total column ozone equivalent to about 3 millimeters of pure O₃ at standard temperature and pressure.[13]Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Ozone (O₃) is an allotrope of dioxygen, comprising three oxygen atoms in a bent molecular geometry with a bond angle of approximately 117°. The structure features resonance between two contributing Lewis forms, yielding equivalent O-O bond lengths of 1.278 Å and partial double-bond character.[14] This delocalized bonding imparts thermodynamic instability, with the decomposition 2O₃ → 3O₂ being exothermic (ΔH = -285 kJ/mol) and spontaneous under standard conditions.[15] At standard temperature and pressure, ozone exists as a pale blue gas with a density of 2.144 g/L, a boiling point of -111.9 °C, and a pungent odor detectable above 0.01 ppm.[16][17] Its solubility in water is moderate (about 1 g/L at 0 °C), decreasing with temperature, and it undergoes slow hydrolysis to form hydrogen peroxide and singlet oxygen.[18] Ozone exhibits high chemical reactivity as a strong electrophilic oxidant, with a standard electrode potential of 2.07 V for O₃ + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → O₂ + H₂O, surpassing many common oxidants.[19] This enables rapid reactions with unsaturated hydrocarbons via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, forming ozonides, and with metals, halides, and sulfides.[20] In aqueous solution, it decomposes via initiation by hydroxide ions, propagating chain reactions involving radicals like O₂⁻ and HO₂.[18] In the stratospheric context, ozone's reactivity drives the Chapman photochemical cycle, balancing production and loss: molecular oxygen photodissociates under shortwave UV (λ < 242 nm) to atomic oxygen, which termolecularly reacts with O₂ and a third body (M) to form O₃; O₃ then absorbs longer-wave UV (200-310 nm), dissociating to O₂ and O, with odd-oxygen (O + O₃) destroyed quadratically via O + O₃ → 2O₂.[21] These gas-phase reactions, first proposed by Sydney Chapman in 1930, establish baseline ozone levels, though catalytic cycles involving NOx, HOx, and ClOx accelerate destruction by converting active species without net consumption.[22] Ozone's UV absorption cross-sections peak near 255 nm, facilitating its protective role while enabling photodissociation.[23]Formation and Maintenance

Photochemical Production in the Stratosphere

The photochemical production of ozone in the stratosphere occurs primarily through the Chapman cycle, a sequence of reactions driven by solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This process begins with the photodissociation of molecular oxygen (O₂) by short-wavelength UV light, where wavelengths shorter than 242 nm provide the energy to break the O=O bond, yielding two oxygen atoms: O₂ + hν (λ < 242 nm) → 2O.[24] These atomic oxygen species then react with intact O₂ molecules in the presence of a third-body collision partner (M, typically N₂ or O₂) to form ozone: O + O₂ + M → O₃ + M.[24] This two-step mechanism constitutes the net production of stratospheric ozone, with the reaction rates increasing with solar zenith angle minimization during daylight hours.[25] Photodissociation of O₂ predominantly occurs via absorption in the Schumann-Runge bands (175-205 nm) and Herzberg continuum (200-242 nm), which penetrate to altitudes above approximately 20 km, where oxygen density is sufficient for subsequent three-body recombination.[26] Ozone formation peaks between 25 and 35 km altitude, corresponding to the region of optimal balance between UV flux and molecular oxygen concentration.[27] While the Chapman cycle accurately predicts the vertical profile shape of ozone, it overestimates concentrations by a factor of about 2, indicating the need for additional catalytic destruction cycles involving species like NOx and HOx to achieve empirical agreement.[27] Empirical measurements confirm daytime dominance of production over loss in the middle stratosphere, with net ozone buildup sustaining the layer's protective role against UV radiation.[25] This cycle's efficiency relies on the stratosphere's low water vapor content, minimizing competing hydroxyl radical formation that could scavenge atomic oxygen.[28] Observations from satellite and balloon-borne instruments, such as those from NASA's Aura mission, validate the photochemical rates, showing production efficiencies tied to solar UV variability.[29]

Sources of Ozone-Forming Precursors

The primary precursor for stratospheric ozone formation is molecular oxygen (O₂), which is photolyzed by ultraviolet radiation at wavelengths below 242 nm to yield two oxygen atoms: O₂ + hν → 2O. One of these atoms then reacts with another O₂ molecule in the presence of a third body (M, typically N₂ or O₂) to form ozone: O + O₂ + M → O₃ + M. This two-step process, central to the Chapman cycle, generates odd oxygen (Oₓ, defined as O + O₃) and accounts for nearly all net photochemical production of stratospheric ozone, with global production rates estimated at approximately 2.3 × 10³¹ molecules per second.[30][31] Atmospheric O₂, comprising 20.95% of the total air volume by mole fraction, is well-mixed throughout the stratosphere due to its long lifetime and diffusive transport, ensuring uniform availability as a precursor regardless of altitude or latitude. The reservoir of O₂ traces its origins to oxygenic photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, algae, and higher plants, which split water molecules (H₂O) to produce O₂ as a byproduct while fixing CO₂ into biomass: 2H₂O → 4H⁺ + 4e⁻ + O₂. This biogenic accumulation began significantly around 2.4 billion years ago during the Great Oxidation Event and has maintained near-current levels for the past 500 million years, with annual gross production exceeding 3 × 10¹⁷ moles but balanced by respiratory and oxidative sinks.[30][32] Minor contributions to odd oxygen production arise from photolysis of trace species like nitrogen dioxide (NO₂ → NO + O), which directly yields atomic oxygen, but such pathways represent less than 1% of total production and are overshadowed by the net ozone-destroying catalytic cycles involving the resulting NOx family (e.g., NO + O₃ → NO₂ + O₂; NO₂ + O → NO + O₂). Sources of stratospheric NO₂ stem predominantly from the oxidation of nitrous oxide (N₂O), transported from the troposphere, where N₂O originates from microbial denitrification in soils (about 60% of emissions) and anthropogenic activities like agriculture (fertilizer use contributing ~40%). However, because NOx cycles convert odd oxygen to even oxygen without net gain, N₂O and its derivatives do not qualify as significant ozone-forming precursors.[33][34]Atmospheric Distribution

Vertical and Latitudinal Profiles

The vertical profile of stratospheric ozone concentration, measured as number density, exhibits a maximum between 20 and 25 kilometers altitude, where photochemical production balances transport and destruction processes.[35] [36] Approximately 90% of atmospheric ozone resides in the stratosphere from 15 to 40 kilometers, with trace amounts in the troposphere below 15 kilometers.[12] In terms of volume mixing ratio, ozone increases with altitude, reaching 8 to 15 parts per million near 30-35 kilometers, reflecting the region's role as the primary production zone driven by ultraviolet photolysis of oxygen. Above 40 kilometers, concentrations decline due to increased dissociation and limited precursor availability.[27] The Brewer-Dobson circulation significantly shapes latitudinal variations in ozone profiles. In the tropics, slow upwelling lifts ozone-rich air to higher altitudes, positioning the number density peak around 26 kilometers.[37] Poleward transport and descent in mid-to-high latitudes accumulate ozone in the lower stratosphere (15-25 kilometers), enhancing concentrations there compared to tropical regions.[38] Total column ozone reflects these dynamics, averaging about 300 Dobson units globally but ranging from 250 units in the tropics to over 400 units at high latitudes, particularly during winter when descent is strongest.[39] This gradient arises from equator-to-pole meridional transport, which redistributes photochemically produced ozone from its tropical source regions.[40] Seasonal modulation amplifies the pattern, with higher columns in the winter hemisphere due to enhanced circulation.[39]Temporal Variations: Seasonal and Solar Cycle Influences

The stratospheric ozone layer experiences pronounced seasonal variations in concentration, driven by the interplay of photochemical production, which requires solar ultraviolet radiation, and dynamical transport via the Brewer-Dobson circulation that shifts ozone-rich air poleward and downward in winter hemispheres.[41] In the upper stratosphere (above approximately 38 km or 4 hPa), ozone mixing ratios typically exhibit a winter maximum and summer minimum, reflecting reduced photodissociation during longer winter nights and enhanced production efficiency in the presence of varying solar zenith angles.[42] Conversely, in the lower stratosphere at high latitudes, ozone abundances increase during winter due to meridional transport of ozone from the tropics and decrease in summer owing to stronger vertical mixing and photochemical loss.[43] Total column ozone displays latitudinal dependence in its seasonal amplitude, with mid-latitude northern hemisphere values peaking at 300–350 Dobson units (DU) in winter (December–February) and dipping to 250–280 DU in summer (June–August), a cycle amplified by subsidence in the winter polar vortex.[44] In the tropics, the seasonal cycle in lower stratospheric ozone features an annual variation with maxima near the tropopause, where upwelling in the ascending branch of the Brewer-Dobson circulation dilutes ozone during northern winter, leading to percentages of mean ozone up to 20–30% higher in the dry season compared to wet.[45] Polar regions show extreme seasonality, with Antarctic total ozone reaching minima below 100 DU in late spring (September–November) due to isolation in the stratospheric vortex and subsequent chemical processing on polar stratospheric clouds, though this is modulated by dynamical recovery in summer.[46] These patterns persist across datasets from satellite instruments like SAGE and ground-based measurements, with amplitudes of 10–20% in total column ozone at extratropical latitudes.[47] Over longer timescales, stratospheric ozone responds to the 11-year solar cycle through variations in solar ultraviolet irradiance, which peaks during solar maximum and enhances ozone production via photodissociation of molecular oxygen.[48] Total column ozone increases by about 2% from solar minimum to maximum, while upper stratospheric mixing ratios (0.7–2 hPa, or ~50–60 km) rise by 5–7%, with the signal manifesting as a single-peak structure aligned with solar activity phases.[49] [50] This modulation arises primarily from UV-driven photochemistry, with secondary dynamical feedbacks like altered stratospheric temperatures amplifying the effect in the tropics and subtropics.[51] Observations from satellite records spanning multiple cycles confirm marginally significant correlations between ozone layers and sunspot numbers, though the response diminishes below 26 km where transport dominates over photochemistry.[52] [53] Solar proton events during high activity can induce short-term ozone reductions in the polar upper stratosphere, but the net cycle effect remains positive for overall abundance.[54]Protective Functions

Ultraviolet Radiation Absorption

Stratospheric ozone absorbs solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation primarily in the UV-C (100–280 nm) and UV-B (280–315 nm) wavelength ranges, with negligible absorption in the UV-A range (315–400 nm).[55] This selective absorption occurs via electronic transitions in the ozone molecule, leading to photodissociation, where a UV photon breaks the O₃ molecule into O₂ and an oxygen atom: \ce{O3 + h\nu -> O2 + O}.[12] The dominant feature is the Hartley band, a broad absorption continuum from approximately 200–310 nm peaking near 255 nm, responsible for the majority of UV protection.[56] Weaker absorption in the Huggins bands (310–400 nm) contributes marginally to UV-B attenuation but does not significantly dissociate ozone.[27] The efficiency of absorption results in nearly complete attenuation of UV-C radiation, with over 99% blocked before reaching the troposphere, and approximately 95% of UV-B radiation absorbed, allowing only a fraction to penetrate to the surface.[2] [57] This process converts photon energy into molecular kinetic energy through subsequent collisions, heating the stratosphere and establishing its temperature inversion relative to lower atmospheric layers.[12] Absorption cross-sections decrease with increasing wavelength within the UV-B band, such that shorter UV-B wavelengths (near 280 nm) are more effectively shielded than those approaching 315 nm.[55] The vertical distribution of ozone, concentrated between 15–35 km altitude, optimizes this shielding, as higher concentrations at peak UV flux altitudes maximize interception.[27]Biological Shielding and Evolutionary Implications

The stratospheric ozone layer functions as a biological shield by absorbing ultraviolet-B (UV-B, 280-315 nm) and ultraviolet-C (UV-C, <280 nm) radiation from the sun, preventing the majority from reaching Earth's surface.[12] This absorption mitigates direct DNA damage in organisms, such as the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and oxidative lesions, which can lead to mutations, cell death, and increased cancer risk in exposed populations.[58] Without this shielding, excessive UV-B would render surface environments lethal to most complex life forms, as UV-C is entirely blocked and UV-B reduced by over 90% under normal conditions.[59][60] In evolutionary terms, the development of a stable ozone layer correlates with the transition of life from aquatic to terrestrial environments during the late Proterozoic and early Phanerozoic eras, approximately 600 million years ago. Prior to this, insufficient atmospheric oxygen limited ozone formation, exposing early land colonizers to high UV fluxes that inhibited multicellular development and favored UV-resistant microbial mats.[61] Recent analyses indicate that ozone instability, driven by fluctuating oxygen levels and atmospheric dynamics, delayed the proliferation of land plants and animals until a protective threshold was achieved around 500-600 million years ago.[62] This shielding enabled the evolution of oxygen-dependent metabolisms and complex ecosystems on land by reducing selective pressure from UV-induced genetic instability, though residual UV-B still influenced adaptive traits like pigmentation and repair mechanisms in surviving lineages.[63][64]Historical Discovery

Early Observations and Measurements (19th-20th Century)

Ozone (O₃) was first identified as a distinct chemical substance in 1839 by German-Swiss chemist Christian Friedrich Schönbein, who detected its pungent odor during experiments involving electrical discharges and electrolysis of water.[65] Schönbein named the gas "ozone" from the Greek word for smell and developed early qualitative test papers using starch-potassium iodide to detect its presence in air, sparking initial interest in atmospheric traces.[66] These methods allowed semiquantitative assessments of near-surface ozone levels, with systematic surface monitoring beginning around 1860 at various European locations using chemical indicators that responded to ozone's oxidizing properties.[65] In the late 19th century, spectroscopic studies shifted focus toward ozone's role in absorbing solar radiation. French physicist Alfred Cornu noted ultraviolet (UV) cutoff in solar spectra in 1879, hinting at atmospheric attenuation, while Walter Noel Hartley in 1881 identified ozone's strong UV absorption bands through laboratory spectra.[22] These findings, combined with Jacques-Louis Soret's 1881 observations of visible absorption (later termed the Chappuis bands), provided indirect evidence of ozone's atmospheric distribution, though quantitative vertical profiling remained elusive due to instrumental limitations.[22] The ozone layer's existence in the upper atmosphere was quantitatively inferred in 1913 by French physicists Charles Fabry and Henri Buisson, who used interferometry to measure solar UV radiation attenuation from mountain observatories in the French Alps.[67] Their analysis of wavelength-dependent absorption yielded an estimate of the total vertical ozone column equivalent to approximately 3 millimeters at standard temperature and pressure, primarily located above 10 kilometers altitude, establishing ozone as a stratospheric constituent responsible for shielding Earth's surface from harmful UV.[22] Advancements accelerated in the 1920s with British physicist Gordon M.B. Dobson's development of the Dobson spectrophotometer, first deployed in 1923 at Oxford.[68] This ground-based instrument measured total column ozone by differentially comparing solar UV intensities at pairs of wavelengths (e.g., 305 nm and 325 nm), where ozone absorbs more strongly at the shorter wavelength, enabling precise Dobson Units (DU) quantification—1 DU equaling 0.01 mm of ozone at STP.[68] Dobson's network expanded in the 1930s, revealing latitudinal gradients (higher ozone at poles, ~350 DU, versus equator ~250 DU) and diurnal variations tied to solar elevation.[68] Complementary efforts, such as Erich Regener's 1934 balloon-borne electrochemical sondes reaching 30 km, confirmed peak ozone concentrations around 20-25 km in the stratosphere.[69] These measurements underscored ozone's photochemical origin and seasonal fluctuations, laying groundwork for global monitoring despite challenges like scattering and instrumental calibration.[68]Advancements in Global Monitoring Networks

The World Ozone Data Centre, established in 1960 by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) under the International Ozone Commission, marked an early step toward centralized global data collection, evolving into the World Ozone and Ultraviolet Radiation Data Centre (WOUDC) operated by Environment and Climate Change Canada.[70] This facility began publishing Ozone Data for the World in 1964 and expanded to include ultraviolet radiation data in 1992, archiving quality-controlled observations from over 400 ground-based stations worldwide, including total column ozone measured via Dobson and Brewer spectrophotometers.[71] By the early 1970s, systematic monitoring of total column and vertical profile ozone expanded through WMO-coordinated networks, providing baseline data for detecting long-term trends with accuracies of a few percent per decade.[72] [73] Satellite-based observations revolutionized global coverage, starting with the launch of NASA's Nimbus-7 satellite on October 24, 1978, equipped with the Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS), which delivered the first daily maps of total ozone columns at 1° x 1.25° resolution using backscatter ultraviolet (BUV) measurements.[74] This instrument operated until 1993, enabling detection of seasonal and latitudinal variations, and was followed by the Earth Probe TOMS launched on July 2, 1996, extending the record through 2006.[75] Subsequent European efforts included the Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME) on ESA's ERS-2 satellite in April 1995, which measured ozone profiles and other trace gases like NO₂ and SO₂ at nadir resolutions up to 40 km × 320 km.[76] Further advancements integrated multiple platforms for cross-validation, with NASA's Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on the Aura satellite, launched in July 2004, providing hyperspectral UV measurements at finer spatial resolutions (13 km × 24 km) and daily global coverage, continuing TOMS-like datasets while tracking aerosols and volcanic influences on ozone.[77] Ground networks, such as NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory stations established since the 1970s and expanded for Antarctic ozone depletion tracking from 1987, complement satellites by offering high-precision profile data via ozonesondes and lidars.[78] [79] Modern systems like ESA's Sentinel-5 Precursor with TROPOMI, operational since October 2017, achieve resolutions down to 3.5 km × 7 km for tropospheric ozone, enhancing detection of urban pollution interactions with stratospheric layers.[80] These networks, under WMO's Global Atmosphere Watch, have sustained uninterrupted records exceeding four decades, confirming ozone recovery signals post-Montreal Protocol at rates of 1-3% per decade in mid-latitudes.[72][69]Depletion Mechanisms

Catalytic Destruction Cycles

Stratospheric ozone undergoes catalytic destruction primarily through cycles involving trace radicals from nitrogen oxides (NOx), hydrogen oxides (HOx), chlorine oxides (ClOx), and bromine oxides (BrOx), which regenerate the catalyst after converting ozone (O3) and atomic oxygen (O) to molecular oxygen (O2) without net consumption of the radical.[81] These processes dominate ozone loss over the null cycle in the Chapman mechanism, with NOx cycles accounting for approximately 70% of natural destruction in the middle stratosphere around 30-40 km altitude.[82] The efficiency arises from the radical's ability to participate repeatedly; for instance, a single chlorine atom can destroy up to 100,000 ozone molecules before removal.[83] In the NOx cycle, nitric oxide (NO) reacts with ozone to form nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and O2, followed by NO2 reacting with atomic oxygen to regenerate NO and produce another O2:NO + O3 → NO2 + O2

NO2 + O → NO + O2

Net: O3 + O → 2O2.

This cycle is sourced from natural NOx emissions, such as from nitrous oxide (N2O) oxidation and solar proton events, and peaks in efficiency where NOx mixing ratios are 5-10 ppbv.[27] HOx cycles, involving hydroxyl (OH) and hydroperoxyl (HO2), operate similarly in the lower stratosphere (below 25 km), contributing about 15-20% of loss through reactions like OH + O3 → HO2 + O2 and HO2 + O → OH + O2, driven by water vapor photolysis.[84] These natural cycles maintain a steady-state ozone profile but are modulated by transport and temperature.[85] Anthropogenic enhancement occurs via ClOx and BrOx from halocarbons like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons, which photodissociate to release Cl and Br atoms in the stratosphere. The ClOx cycle mirrors NOx: Cl + O3 → ClO + O2; ClO + O → Cl + O2, but chlorine's reservoir species (e.g., ClONO2) partition into active forms on polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) during winter, activating up to 90% of total chlorine as ClO.[86] Bromine cycles are more potent per atom due to faster kinetics; Br + O3 → BrO + O2; BrO + O → Br + O2, with BrO concentrations of 10-20 pptv enabling significant loss even at lower abundances (3-5 pptv total Br).[27] Synergistic ClO-BrO cycles amplify depletion: ClO + BrO → Cl + Br + O2, netting two ozone losses per pair, contributing up to 40% of polar springtime destruction.[87] Observational and modeling data from aircraft campaigns and satellites confirm these cycles' roles, with NOx and HOx explaining mid-latitude losses and halogen cycles driving polar minima, where combined ClOx-BrOx-HOx contributions exceed 80% during ozone hole events.[88] While natural variability (e.g., volcanic SO2 injecting NOx) influences rates, anthropogenic halogens increased ClOx by a factor of 100 since pre-industrial levels, verified by balloon-borne and ground-based measurements since the 1970s.[12]

Anthropogenic Halocarbons: CFCs and Their Role

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), synthetic compounds consisting of carbon, chlorine, and fluorine atoms, were developed in the 1920s and widely adopted from the 1930s onward for applications including refrigeration, air conditioning, aerosol propellants, and foam blowing agents due to their chemical stability, non-toxicity, and non-flammability.[89] These halocarbons are inert in the troposphere, allowing them to persist for decades and gradually ascend to the stratosphere via atmospheric mixing.[90] Global production of major CFCs like CFC-11 and CFC-12 peaked in the late 1980s, with annual emissions reaching several hundred thousand metric tons before regulatory interventions.[91] In 1974, chemists Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland published a seminal analysis predicting that stratospheric photolysis of CFCs would release chlorine atoms, initiating catalytic cycles destructive to ozone.[92] Under ultraviolet radiation at altitudes above 30 km, CFCs such as CFCl₃ dissociate: CFCl₃ + hν → CFCl₂ + Cl. The freed chlorine radical then reacts with ozone: Cl + O₃ → ClO + O₂, followed by ClO + O → Cl + O₂, yielding a net loss of one ozone molecule and one atomic oxygen per cycle, with the chlorine atom regenerated to propagate the process.[93] A single chlorine atom can catalytically destroy up to 100,000 ozone molecules before sequestration into less reactive forms like HCl or ClONO₂.[94] This chain reaction amplifies the impact of even trace chlorine levels, with stratospheric chlorine concentrations rising from near-zero pre-1950 to over 3 parts per billion by volume in the 1990s, directly attributable to anthropogenic CFC emissions.[91] Empirical observations confirmed the CFC-ozone link, particularly in the Antarctic, where polar stratospheric clouds facilitate chlorine activation during winter darkness, leading to rapid springtime depletion. Measurements from the British Antarctic Survey in 1985 revealed total column ozone losses exceeding 50% over the continent, correlating spatially and temporally with elevated stratospheric chlorine monoxide (ClO) from CFC breakdown—levels up to 1 ppbv, far above natural baselines.[91] Satellite and ground-based data from NASA and NOAA showed global ozone declines of 3-6% per decade from the 1970s to 1990s, with isotopic analysis of chlorine reservoirs and emission inventories excluding natural sources like volcanoes as primary drivers, as their chlorine inputs are water-soluble and deposit in the troposphere rather than reaching the stratosphere.[95] Post-Montreal Protocol reductions in CFC emissions, which dropped over 99% since 1989, have yielded corresponding declines in stratospheric chlorine and ozone recovery signals, providing causal evidence of CFCs' dominant role in observed depletions.[96] While other halocarbons like halons contribute additively, CFCs accounted for the majority of anthropogenic chlorine loading, with their phase-out averting projected ozone losses of up to 50% by 2050 absent intervention.[6]Natural Contributors: Volcanic Eruptions and Solar Activity

Volcanic eruptions contribute to stratospheric ozone depletion by injecting sulfur dioxide (SO₂) and other gases directly into the ozone layer, where they form sulfate aerosols that serve as surfaces for heterogeneous chemical reactions. These reactions activate reservoir species like chlorine nitrate (ClONO₂) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) into reactive forms such as chlorine (Cl) and bromine (Br), which then catalytically destroy ozone molecules via cycles similar to those enhanced by polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs).[97] The effect is temporary, lasting 1–3 years post-eruption, as aerosols gradually settle out, but can amplify depletion in regions with existing halogens from anthropogenic sources.[98] No major eruptions on the scale of historical events have occurred since the 1991 Mount Pinatubo event to significantly alter global trends in recent decades.[99] The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines exemplifies this mechanism, releasing approximately 20 million tons of SO₂ into the stratosphere and forming a persistent aerosol veil that increased particle surface area by factors of 10–100. This led to enhanced chlorine activation and a global ozone reduction of about 2% on average, with losses up to 5–8% in mid-latitudes and greater impacts near the tropics due to upwelling dynamics.[98] [100] Observations from satellite and ground-based measurements confirmed the depletion peaked in 1992–1993, coinciding with aerosol optical depth maxima exceeding 0.1 at 20–25 km altitude.[101] Smaller eruptions, such as El Chichón in 1982, produced similar but less pronounced effects, underscoring that only explosive events with plume injections above 20 km significantly influence ozone.[48] Solar activity modulates stratospheric ozone through variations in ultraviolet (UV) irradiance over the 11-year solar cycle, with lower ozone levels during solar minima due to reduced photolysis of oxygen (O₂) and nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), which limits ozone production rates. Ozone abundance typically varies by 1–2% globally, with mid-stratospheric concentrations (around 30–40 km) showing the strongest response, as UV flux in the 200–300 nm range—responsible for O₂ dissociation—increases by 6–8% from minimum to maximum.[97] [102] This cycle-driven variation contributes to natural depletion episodes at solar minimum, when ozone can be 2% lower than at maximum, based on observations from multiple cycles since the 1960s using instruments like the Solar Backscatter Ultraviolet (SBUV) series.[97] Extreme solar events, such as solar proton events (SPEs) during high activity phases, provide additional depletion pathways by precipitating high-energy protons into the polar atmosphere, producing odd nitrogen (NOx) species that catalytically destroy ozone through the NOx + Ox cycle. Major SPEs, like those in October–November 2003, caused localized polar ozone losses of 20–30% in the mesosphere and upper stratosphere over days to weeks, with global effects minimal but detectable via increased HOx and NOx.[103] [104] Regular 11-year cycle influences are dwarfed by anthropogenic forcings but explain decadal fluctuations superimposed on long-term trends, as evidenced by Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) data showing single-peak solar signals in tropical ozone profiles.[50] Overall, solar-driven depletion remains secondary to halogen catalysis but introduces variability that can mask or exacerbate recovery signals.[97]The Antarctic Ozone Hole

Initial Detection in 1985

In May 1985, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS)—Joseph Farman, Brian Gardiner, and Jonathan Shanklin—published observations from ground-based measurements revealing unprecedented seasonal depletion of stratospheric ozone over Antarctica.[105] [106] Their analysis, based on data from a Dobson spectrophotometer at the Halley research station (75.6°S, 26.2°W), showed that total column ozone in October—the Antarctic spring—had declined by approximately 40% since the mid-1970s, reaching minima as low as 180 Dobson units (DU) in 1984 compared to historical averages exceeding 300 DU in the 1950s and 1960s.[105] [107] These instruments measure total ozone by detecting ultraviolet light absorption at specific wavelengths, providing reliable vertical column totals from long-term records starting in 1957 at Halley.[108] The depletion was sharply confined to the austral spring, with ozone levels recovering somewhat by December but exhibiting a trend of accelerating loss not predicted by contemporaneous atmospheric models, which anticipated gradual global thinning rather than a localized "hole."[105] [109] Farman et al. linked the phenomenon to elevated chlorine oxide (ClOx) levels interacting with nitrogen oxides (NOx) in the presence of polar stratospheric clouds, catalyzed by anthropogenic chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), though they noted the interaction's efficiency exceeded prior theoretical expectations.[105] Complementary data from the BAS station at Argentine Islands (65.2°S) showed milder but concurrent declines of about 10-15%, underscoring the depletion's intensification toward the pole.[105] Initial satellite observations from NASA's Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) aboard Nimbus-7, operational since 1978, had not flagged the anomaly prominently, as extreme lows were often discarded as instrumental errors or attributed to data flagging thresholds exceeding 220 DU—the threshold later defining the ozone hole.[109] [110] The BAS ground data thus provided the first unambiguous evidence, prompting re-examination of satellite records that confirmed the hole's persistence and scale, with areal extents covering millions of square kilometers where ozone fell below 220 DU annually from September to November.[111] This discovery highlighted the value of sustained, site-specific monitoring over broad but potentially biased remote sensing, as the polar vortex's isolation amplified chemical losses undetected in zonal averages.[112]Dynamical and Chemical Processes Driving Formation

The Antarctic ozone hole forms primarily through the isolation of stratospheric air within the polar vortex, a dynamical barrier that confines cold, processed air masses during the austral winter. This vortex, strongest from June to September, arises from the conservation of angular momentum and the Coriolis effect acting on westerly winds around the pole, enhanced by the Southern Hemisphere's relative lack of continental disruptions to planetary wave propagation, leading to greater stability compared to the Arctic. Temperatures within the vortex drop below 190 K due to radiative cooling in the absence of solar heating, preventing mixing with warmer mid-latitude air and allowing chemical reservoirs to accumulate without dilution.[113][114] These extreme cold conditions enable the formation of polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs), composed of nitric acid trihydrate (Type I, stable above ~188 K) or water ice (Type II, below ~188 K), which provide heterogeneous surfaces for chemical reactions converting inert chlorine reservoirs into active forms. On PSC particles, reactions such as ClONO₂ + HCl → Cl₂ + HNO₃ activate chlorine, while simultaneous removal of nitrogen oxides via sedimentation of nitric acid-containing particles (denitrification) reduces chlorine deactivation, sustaining high levels of reactive ClO for weeks. Volcanic enhancements to sulfate aerosols can lower the effective temperature threshold for PSC formation, amplifying activation under marginally cold conditions.[115][114][116] Upon the return of sunlight in late August to early September, ultraviolet photolysis rapidly converts Cl₂ to atomic chlorine (Cl₂ + hν → 2Cl), initiating catalytic ozone destruction cycles, including the ClO + O₃ → ClO + O₂ followed by ClO + O → Cl + O₂ (net: O₃ + O → 2O₂), and the ClO dimer mechanism (2ClO → Cl₂O₂ → 2Cl + O₂) that dominates under high ClO concentrations. These cycles, amplified by bromine synergies, can deplete up to 3.5 parts per million volume of ozone in severe years like 2020, with the vortex's containment preventing replenishment via the weaker Brewer-Dobson circulation in the Southern Hemisphere. The hole peaks in September–October, dissipating as vortex breakdown in November mixes in ozone-rich air, though dynamical variability, such as sudden stratospheric warmings (rare in Antarctica), can modulate annual severity.[117][118][117]International Policy Responses

Pre-Montreal Protocol Assessments (1970s-1980s)

In 1974, chemists Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland published a seminal paper proposing that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), widely used as aerosol propellants and refrigerants, could catalytically destroy stratospheric ozone after transport to the upper atmosphere, where ultraviolet radiation would release chlorine atoms initiating chain reactions.[92] Their model predicted that unchecked CFC emissions could reduce global ozone levels by up to several percent over decades, potentially increasing ultraviolet radiation reaching Earth's surface and elevating risks of skin cancer and ecosystem disruption, though empirical measurements of depletion were not yet available to confirm the hypothesis.[92] The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) conducted initial assessments in response, releasing the 1976 report Halocarbons: Effects on Stratospheric Ozone, which modeled a probable 7% global ozone reduction (with uncertainty ranging from 2% to 20%) from continued CFC emissions at 1970s rates, endorsing the Molina-Rowland mechanism as plausible based on laboratory kinetics and atmospheric transport simulations.[119] This was followed by a 1979 NAS report, Protection Against Depletion of Stratospheric Ozone by Chlorofluorocarbons, which refined projections to a 5-9% depletion under business-as-usual scenarios while recommending regulatory controls on non-essential CFC uses to mitigate risks.[120] A 1982 NAS update, Causes and Effects of Stratospheric Ozone Reduction, maintained concerns over chlorine loading from CFCs, estimating steady-state depletions of 4-7% globally but highlighting greater polar vulnerabilities due to dynamical factors like stratospheric cooling.[121] These assessments informed U.S. policy actions, culminating in a 1978 joint regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Consumer Product Safety Commission banning non-essential CFC propellants in aerosols effective October 15, 1978, which reduced U.S. CFC emissions by about 40% from peak levels despite industry arguments that models overestimated risks and alternatives were unavailable.[122] Internationally, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) initiated coordinating assessments, with the first World Meteorological Organization (WMO)/UNEP scientific review in 1981 synthesizing data to affirm CFC-ozone linkages and urge global emission curbs, setting the stage for diplomatic negotiations.[123] Early models relied on one-dimensional atmospheric simulations, which later critiques noted underemphasized natural variability and heterogeneous chemistry, but contemporaneous evidence from balloon-borne ozone soundings showed no definitive global decline by the early 1980s, prompting calls for enhanced monitoring.[121]Montreal Protocol: Key Provisions and Amendments

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, adopted on September 16, 1987, in Montreal, Canada, and entering into force on January 1, 1989, established a framework for phasing out the production and consumption of specified ozone-depleting substances (ODS).[124] It initially targeted chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) listed in Annex A, Groups I and II, and halons in Group I, requiring Parties classified under Article 2 (primarily developed countries) to freeze CFC consumption at 1986 levels by July 1, 1989, reduce it by 20% by 1993, and by 50% by 1998, while halons faced a freeze at 1986 levels by January 1, 1992, followed by a 20% reduction by 1996.[124] Article 5 countries (developing nations) received a grace period of 10 years for compliance, with provisions for technology transfer and financial assistance to support implementation.[124] The Protocol also included trade restrictions on ODS with non-Parties and mechanisms for data reporting and non-compliance procedures.[124] Subsequent amendments and adjustments expanded the list of controlled substances and accelerated phase-out timelines, transforming the original modest reductions into near-total global elimination of key ODS. The London Amendment of June 29, 1990, introduced complete phase-out targets for CFCs and halons by 2000 for Article 2 Parties, added other fully halogenated CFCs (Annex B, Group I), carbon tetrachloride (Group III), and methyl chloroform (Group II), and established controls on hydrobromofluorocarbons (HBFCs).[125] The Copenhagen Amendment of November 25, 1992, advanced CFC phase-out to 1996, added hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) in Annex C with a 2020 elimination deadline for Article 2 Parties, and included methyl bromide (Annex E) for quarantine and pre-shipment uses with exemptions.[125] Further refinements came via the Vienna Adjustment of 1995, Montreal Amendment of September 1997 (adding bromochloromethane), and Beijing Amendment of December 1999 (controlling n-propyl bromide).[125] The Kigali Amendment, adopted on October 15, 2016, and entering into force on January 1, 2019, extended the Protocol's scope to hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), potent greenhouse gases used as ODS replacements but not ozone-depleting themselves, mandating a global phase-down starting with an 85% reduction baseline by 2036 for most Article 2 Parties (2011-2013 average levels) and later timelines for Article 5 countries.[125]| Amendment/Adjustment | Date Adopted | Key Changes |

|---|---|---|

| London Amendment | June 29, 1990 | Accelerated phase-outs to 2000; added Annex B substances (other CFCs, carbon tetrachloride, methyl chloroform); controls on HBFCs.[125] |

| Copenhagen Amendment | November 25, 1992 | Advanced CFC elimination to 1996; added HCFCs (Annex C, phase-out by 2020 for Article 2); methyl bromide (Annex E) with exemptions.[125] |

| Montreal Amendment | September 15, 1997 | Controls on bromochloromethane; adjustments to HCFC and methyl bromide schedules.[125] |

| Beijing Amendment | December 3, 1999 | Added n-propyl bromide to controls.[125] |

| Kigali Amendment | October 15, 2016 | HFC phase-down: baseline freeze 2011-2013 for developed, 2020-2022 for most developing; 80-85% reduction by late 2040s.[125] |

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}+{}{\mathit {h}}\mathrm {\nu } {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{\mathrm {uv} }}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}2\,\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/02da261d68d665489d6ed60561fcd9b539d4bc20)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {O} {}+{}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}\mathrel {\longleftrightarrow } {}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0786b12e0daa954821e763a13a4c25ce2a5f7f06)