Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

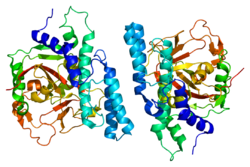

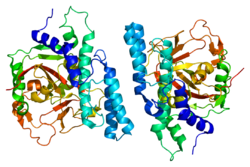

PARP1

View on WikipediaPoly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1) also known as NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase 1 or poly[ADP-ribose] synthase 1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PARP1 gene.[5] It is the most abundant of the PARP family of enzymes, accounting for 90% of the NAD+ used by the family.[6] PARP1 is mostly present in cell nucleus, but cytosolic fraction of this protein was also reported.[7]

Function

[edit]PARP1 works:

- By using NAD+ to synthesize poly ADP ribose (PAR) and transferring PAR moieties to proteins (ADP-ribosylation).[8]

- In conjunction with BRCA, which acts on double strands; members of the PARP family act on single strands; or, when BRCA fails, PARP takes over those jobs as well (in a DNA repair context).

PARP1 is involved in:

- Differentiation, proliferation, and tumor transformation

- Normal or abnormal recovery from DNA damage

- May be the site of mutation in Fanconi anemia[citation needed]

- Induction of inflammation.[9]

- The pathophysiology of type I diabetes.[10]

PARP1 is activated by:

- Helicobacter pylori in the development and proliferation of gastric cancer.[11]

Role in DNA damage repair

[edit]PARP1 acts as a first responder that detects DNA damage and then facilitates choice of repair pathway.[12] PARP1 contributes to repair efficiency by ADP-ribosylation of histones leading to decompaction of chromatin structure, and by interacting with and modifying multiple DNA repair factors.[6] PARP1 is implicated in the regulation of several DNA repair processes including the pathways of nucleotide excision repair, non-homologous end joining, microhomology-mediated end joining, homologous recombinational repair, and DNA mismatch repair.[12]

PARP1 has a role in repair of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) breaks. Knocking down intracellular PARP1 levels with siRNA or inhibiting PARP1 activity with small molecules reduces repair of ssDNA breaks. In the absence of PARP1, when these breaks are encountered during DNA replication, the replication fork stalls, and double-strand DNA (dsDNA) breaks accumulate. These dsDNA breaks are repaired via homologous recombination (HR) repair, a potentially error-free repair mechanism. For this reason, cells lacking PARP1 show a hyper-recombinagenic phenotype (e.g., an increased frequency of HR),[13][14][15] which has also been observed in vivo in mice using the pun assay.[16] Thus, if the HR pathway is functioning, PARP1 null mutants (cells without functioning PARP1) do not show an unhealthy phenotype, and in fact, PARP1 knockout mice show no negative phenotype and no increased incidence of tumor formation.[17]

Role in inflammation

[edit]PARP1 is required for NF-κB transcription of proinflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 6, and inducible nitric oxide synthase.[9][18] PARP1 activity contributes to the proinflammatory macrophages that increase with age in many tissues.[19] ADP-riboyslation of the HMGB1 high-mobility group protein by PARP1 inhibits removal of apoptotic cells, thereby sustaining inflammation.[20]

In asthma PARP1 facilitates recruitment and function of immune cells, including CD4+ T-cells, eosinophils, and dendritic cells.[18]

Over-expression in cancer

[edit]PARP1 is one of six enzymes required for the highly error-prone DNA repair pathway microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ).[21] MMEJ is associated with frequent chromosome abnormalities such as deletions, translocations, inversions and other complex rearrangements. When PARP1 is up-regulated, MMEJ is increased, causing genome instability.[22] PARP1 is up-regulated and MMEJ is increased in tyrosine kinase-activated leukemias.[22]

PARP1 is also over-expressed when its promoter region ETS site is epigenetically hypomethylated, and this contributes to progression to endometrial cancer,[23] BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer,[24] and BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer.[25]

PARP1 is also over-expressed in a number of other cancers, including neuroblastoma,[26] HPV infected oropharyngeal carcinoma,[27] testicular and other germ cell tumors,[28] Ewing's sarcoma,[29] malignant lymphoma,[30] breast cancer,[31] and colon cancer.[32]

Cancers are very often deficient in expression of one or more DNA repair genes, but over-expression of a DNA repair gene is less usual in cancer. For instance, at least 36 DNA repair enzymes, when mutationally defective in germ line cells, cause increased risk of cancer (hereditary cancer syndromes).[citation needed] (Also see DNA repair-deficiency disorder.) Similarly, at least 12 DNA repair genes have frequently been found to be epigenetically repressed in one or more cancers.[citation needed] (See also Epigenetically reduced DNA repair and cancer.) Ordinarily, deficient expression of a DNA repair enzyme results in increased un-repaired DNA damage which, through replication errors (translesion synthesis), lead to mutations and cancer. However, PARP1 mediated MMEJ repair is highly inaccurate, so in this case, over-expression, rather than under-expression, apparently leads to cancer.

Interaction with BRCA1 and BRCA2

[edit]Both BRCA1 and BRCA2 are at least partially necessary for the HR pathway to function. Cells that are deficient in BRCA1 or BRCA2 have been shown to be highly sensitive to PARP1 inhibition or knock-down, resulting in cell death by apoptosis, in stark contrast to cells with at least one good copy of both BRCA1 and BRCA2. Many breast cancers have defects in the BRCA1/BRCA2 HR repair pathway due to mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2, or other essential genes in the pathway (the latter termed cancers with "BRCAness"). Tumors with BRCAness are hypothesized to be highly sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors, and it has been demonstrated in mice that these inhibitors can both prevent BRCA1/2-deficient xenografts from becoming tumors and eradicate tumors having previously formed from BRCA1/2-deficient xenografts.

Application to cancer therapy

[edit]PARP1 inhibitors are being tested for effectiveness in cancer therapy.[33] It is hypothesized that PARP1 inhibitors may prove highly effective therapies for cancers with BRCAness, due to the high sensitivity of the tumors to the inhibitor and the lack of deleterious effects on the remaining healthy cells with functioning BRCA HR pathway. This is in contrast to conventional chemotherapies, which are highly toxic to all cells and can induce DNA damage in healthy cells, leading to secondary cancer generation.[34][35]

Aging

[edit]PARP activity (which is mainly due to PARP1) measured in the permeabilized mononuclear leukocyte blood cells of thirteen mammalian species (rat, guinea pig, rabbit, marmoset, sheep, pig, cattle, pigmy chimpanzee, horse, donkey, gorilla elephant and man) correlates with maximum lifespan of the species.[36] Lymphoblastoid cell lines established from blood samples of humans who were centenarians (100 years old or older) have significantly higher PARP activity than cell lines from younger (20 to 70 years old) individuals.[37] The Wrn protein is deficient in persons with Werner syndrome, a human premature aging disorder. PARP1 and Wrn proteins are part of a complex involved in the processing of DNA breaks.[38] These findings indicate a linkage between longevity and PARP-mediated DNA repair capability. Furthermore, PARP can also act against production of reactive oxygen species, which may contribute to longevity by inhibiting oxidative damage to DNA and proteins.[39] These observations suggest that PARP activity contributes to mammalian longevity, consistent with the DNA damage theory of aging.[citation needed]

PARP1 appears to be resveratrol's primary functional target through its interaction with the tyrosyl tRNA synthetase (TyrRS).[40] Tyrosyl tRNA synthetase translocates to the nucleus under stress conditions stimulating NAD+-dependent auto-poly-ADP-ribosylation of PARP1,[40] thereby altering the functions of PARP1 from a chromatin architectural protein to a DNA damage responder and transcription regulator.[41]

The messenger RNA level and protein level of PARP1 is controlled, in part, by the expression level of the ETS1 transcription factor which interacts with multiple ETS1 binding sites in the promoter region of PARP1.[42] The degree to which the ETS1 transcription factor can bind to its binding sites on the PARP1 promoter depends on the methylation status of the CpG islands in the ETS1 binding sites in the PARP1 promoter.[23] If these CpG islands in ETS1 binding sites of the PARP1 promoter are epigenetically hypomethylated, PARP1 is expressed at an elevated level.[23][24]

Cells from older humans (69 to 75 years of age) have a constitutive expression level of both PARP1 and PARP2 genes reduced by half, compared to their levels in young adult humans (19 to 26 years old). However, centenarians (humans aged 100 to 107 years of age) have constitutive expression of PARP1 at levels similar to those of young individuals.[43] This high level of PARP1 expression in centenarians was shown to allow more efficient repair of H2O2 sublethal oxidative DNA damage.[43] Higher DNA repair is thought to contribute to longevity (see DNA damage theory of aging). The high constitutive levels of PARP1 in centenarians were thought to be due to altered epigenetic control of PARP1 expression.[43]

Both sirtuin 1 and PARP1 have a roughly equal affinity for the NAD+ that both enzymes require for activity.[44] But DNA damage can increase levels of PARP1 more than 100-fold, leaving little NAD+ for SIRT1.[44]

Role in cell death

[edit]Following severe DNA damage, excessive activation of PARP1 can lead to cell death.[45] Initially, overactivation of the enzyme was linked to apoptotic cell death[46][47] but later, PARP1-mediated cell death turned out to show characteristics of necrotic cell death (i.e. early plasma membrane disruption, structural and functional mitochondrial alterations).[48][49] These findings provided explanation for previous and subsequent reports demonstrating tissue protective effects of PARP inhibitors and the PARP1 knockout phenotypes in various models of ischemia-reperfusion injury (e.g. in stroke, in the heart and in the gut) where oxidative stress-induced cell death is a central cellular event.[50] Later, apoptosis inducing factor (AIF; a misnomer) was identified as a key mediator of the PARP1-mediated regulated necrotic cell death pathway termed parthanatos.[51]

Plant PARP1

[edit]Plants have a PARP1 with substantial similarity to animal PARP1, and roles of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in plant responses to DNA damage, infection and other stresses have been studied.[52][53] Intriguingly, in Arabidopsis thaliana (and presumably other plants), PARP2 plays more significant roles than PARP1 in protective responses to DNA damage and bacterial pathogenesis.[54] The plant PARP2 carries PARP regulatory and catalytic domains with only intermediate similarity to PARP1, and carries N-terminal SAP DNA binding motifs rather than the Zn-finger DNA binding motifs of plant and animal PARP1 proteins.[54]

Interactions

[edit]PARP1 has been shown to interact with:

See also

[edit]- DNA damage theory of aging

- Maximum lifespan

- Olaparib – a PARP inhibitor

- PARP inhibitor class of investigational anti-cancer drugs

- Parthanatos

- Poly ADP ribose polymerase

- Senescence

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000143799 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026496 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Ha HC, Snyder SH (August 2000). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in the nervous system". Neurobiology of Disease. 7 (4): 225–39. doi:10.1006/nbdi.2000.0324. PMID 10964595. S2CID 41201067.

- ^ a b Xie N, Zhang L, Gao W, Huang C, Zou B (2020). "NAD + metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential". Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 5 (1) 227. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00311-7. PMC 7539288. PMID 33028824.

- ^ Karpińska, Aneta (2021). "Quantitative analysis of biochemical processes in living cells at a single-molecule level: a case of olaparib–PARP1 (DNA repair protein) interactions" (PDF). Analyst. 146 (23): 7131–7143. Bibcode:2021Ana...146.7131K. doi:10.1039/D1AN01769A. PMID 34726203. S2CID 240110114.

- ^ Nilov, DK; Pushkarev, SV; Gushchina, IV; Manasaryan, GA; Kirsanov, KI; Švedas, VK (2020). "Modeling of the enzyme-substrate complexes of human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1". Biochemistry (Moscow). 85 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1134/S0006297920010095. PMID 32079521. S2CID 211028760.

- ^ a b Mangerich A, Bürkle A (2012). "Pleiotropic cellular functions of PARP1 in longevity and aging: genome maintenance meets inflammation". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2012 321653. doi:10.1155/2012/321653. PMC 3459245. PMID 23050038.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: PARP1 poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 1".

- ^ Nossa CW, Jain P, Tamilselvam B, Gupta VR, Chen LF, Schreiber V, et al. (November 2009). "Activation of the abundant nuclear factor poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 by Helicobacter pylori". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (47): 19998–20003. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10619998N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906753106. PMC 2785281. PMID 19897724.

- "Team finds link between stomach-cancer bug and cancer-promoting factor". Medical Xpress. January 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Pascal JM (November 2018). "The comings and goings of PARP-1 in response to DNA damage". DNA Repair. 71: 177–182. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.08.022. PMC 6637744. PMID 30177435.

- ^ Godon C, Cordelières FP, Biard D, Giocanti N, Mégnin-Chanet F, Hall J, Favaudon V (August 2008). "PARP inhibition versus PARP-1 silencing: different outcomes in terms of single-strand break repair and radiation susceptibility". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (13): 4454–64. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn403. PMC 2490739. PMID 18603595.

- ^ Schultz N, Lopez E, Saleh-Gohari N, Helleday T (September 2003). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) has a controlling role in homologous recombination". Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (17): 4959–64. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg703. PMC 212803. PMID 12930944.

- ^ Waldman AS, Waldman BC (November 1991). "Stimulation of intrachromosomal homologous recombination in mammalian cells by an inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribosylation)". Nucleic Acids Research. 19 (21): 5943–7. doi:10.1093/nar/19.21.5943. PMC 329051. PMID 1945881.

- ^ Claybon A, Karia B, Bruce C, Bishop AJ (November 2010). "PARP1 suppresses homologous recombination events in mice in vivo". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (21): 7538–45. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq624. PMC 2995050. PMID 20660013.

- ^ Wang ZQ, Auer B, Stingl L, Berghammer H, Haidacher D, Schweiger M, Wagner EF (March 1995). "Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease". Genes & Development. 9 (5): 509–20. doi:10.1101/gad.9.5.509. PMID 7698643.

- ^ a b Sethi GS, Dharwal V, Naura AS (2017). "Poly(ADP-Ribose)Polymerase-1 in Lung Inflammatory Disorders: A Review". Frontiers in Immunology. 8 1172. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01172. PMC 5610677. PMID 28974953.

- ^ Yarbro JR, Emmons RS, Pence BD (2020). "Macrophage Immunometabolism and Inflammaging: Roles of Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Cellular Senescence, CD38, and NAD". Immunometabolism. 2 (3) e200026. doi:10.20900/immunometab20200026. PMC 7409778. PMID 32774895.

- ^ Pazzaglia S, Pioli C (2019). "Multifaceted Role of PARP-1 in DNA Repair and Inflammation: Pathological and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer and Non-Cancer Diseases". Cells. 9 (1): 41. doi:10.3390/cells9010041. PMC 7017201. PMID 31877876.

- ^ Sharma S, Javadekar SM, Pandey M, Srivastava M, Kumari R, Raghavan SC (March 2015). "Homology and enzymatic requirements of microhomology-dependent alternative end joining". Cell Death & Disease. 6 (3): e1697. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.58. PMC 4385936. PMID 25789972.

- ^ a b Muvarak N, Kelley S, Robert C, Baer MR, Perrotti D, Gambacorti-Passerini C, et al. (April 2015). "c-MYC Generates Repair Errors via Increased Transcription of Alternative-NHEJ Factors, LIG3 and PARP1, in Tyrosine Kinase-Activated Leukemias". Molecular Cancer Research. 13 (4): 699–712. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0422. PMC 4398615. PMID 25828893.

- ^ a b c Bi FF, Li D, Yang Q (2013). "Hypomethylation of ETS transcription factor binding sites and upregulation of PARP1 expression in endometrial cancer". BioMed Research International. 2013 946268. doi:10.1155/2013/946268. PMC 3666359. PMID 23762867.

- ^ a b Li D, Bi FF, Cao JM, Cao C, Li CY, Liu B, Yang Q (January 2014). "Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 transcriptional regulation: a novel crosstalk between histone modification H3K9ac and ETS1 motif hypomethylation in BRCA1-mutated ovarian cancer". Oncotarget. 5 (1): 291–7. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1549. PMC 3960209. PMID 24448423.

- ^ Bi FF, Li D, Yang Q (February 2013). "Promoter hypomethylation, especially around the E26 transformation-specific motif, and increased expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 in BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer". BMC Cancer. 13 90. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-90. PMC 3599366. PMID 23442605.

- ^ Newman EA, Lu F, Bashllari D, Wang L, Opipari AW, Castle VP (March 2015). "Alternative NHEJ Pathway Components Are Therapeutic Targets in High-Risk Neuroblastoma". Molecular Cancer Research. 13 (3): 470–82. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0337. PMID 25563294.

- ^ Liu Q, Ma L, Jones T, Palomero L, Pujana MA, Martinez-Ruiz H, et al. (December 2018). "Subjugation of TGFβ Signaling by Human Papilloma Virus in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Shifts DNA Repair from Homologous Recombination to Alternative End Joining". Clinical Cancer Research. 24 (23): 6001–6014. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1346. PMID 30087144.

- ^ Mego M, Cierna Z, Svetlovska D, Macak D, Machalekova K, Miskovska V, et al. (July 2013). "PARP expression in germ cell tumours". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 66 (7): 607–12. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201088. PMID 23486608. S2CID 535704.

- ^ Newman RE, Soldatenkov VA, Dritschilo A, Notario V (2002). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase turnover alterations do not contribute to PARP overexpression in Ewing's sarcoma cells". Oncology Reports. 9 (3): 529–32. doi:10.3892/or.9.3.529. PMID 11956622.

- ^ Tomoda T, Kurashige T, Moriki T, Yamamoto H, Fujimoto S, Taniguchi T (August 1991). "Enhanced expression of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase gene in malignant lymphoma". American Journal of Hematology. 37 (4): 223–7. doi:10.1002/ajh.2830370402. PMID 1907096. S2CID 26905918.

- ^ Rojo F, García-Parra J, Zazo S, Tusquets I, Ferrer-Lozano J, Menendez S, et al. (May 2012). "Nuclear PARP-1 protein overexpression is associated with poor overall survival in early breast cancer". Annals of Oncology. 23 (5): 1156–64. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr361. PMID 21908496.

- ^ Dziaman T, Ludwiczak H, Ciesla JM, Banaszkiewicz Z, Winczura A, Chmielarczyk M, et al. (2014). "PARP-1 expression is increased in colon adenoma and carcinoma and correlates with OGG1". PLOS ONE. 9 (12) e115558. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k5558D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115558. PMC 4272268. PMID 25526641.

- ^ Rajman L, Chwalek K, Sinclair DA (2018). "Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence". Cell Metabolism. 27 (3): 529–547. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.011. PMC 6342515. PMID 29514064.

- ^ Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, et al. (April 2005). "Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase". Nature. 434 (7035): 913–7. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..913B. doi:10.1038/nature03443. PMID 15829966. S2CID 4391043.

- ^ Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. (April 2005). "Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy". Nature. 434 (7035): 917–21. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..917F. doi:10.1038/nature03445. PMID 15829967. S2CID 4364706.

- ^ Grube K, Bürkle A (December 1992). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in mononuclear leukocytes of 13 mammalian species correlates with species-specific life span". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (24): 11759–63. Bibcode:1992PNAS...8911759G. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.24.11759. PMC 50636. PMID 1465394.

- ^ Muiras ML, Müller M, Schächter F, Bürkle A (April 1998). "Increased poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in lymphoblastoid cell lines from centenarians". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 76 (5): 346–54. doi:10.1007/s001090050226. PMID 9587069. S2CID 24616650.

- ^ Lebel M, Lavoie J, Gaudreault I, Bronsard M, Drouin R (May 2003). "Genetic cooperation between the Werner syndrome protein and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in preventing chromatid breaks, complex chromosomal rearrangements, and cancer in mice". The American Journal of Pathology. 162 (5): 1559–69. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64290-3. PMC 1851180. PMID 12707040.

- ^ Liu Q, Gheorghiu L, Drumm M, Clayman R, Eidelman A, Wszolek MF, et al. (May 2018). "PARP-1 inhibition with or without ionizing radiation confers reactive oxygen species-mediated cytotoxicity preferentially to cancer cells with mutant TP53". Oncogene. 37 (21): 2793–2805. doi:10.1038/s41388-018-0130-6. PMC 5970015. PMID 29511347.

- ^ a b Sajish M, Schimmel P (March 2015). "A human tRNA synthetase is a potent PARP1-activating effector target for resveratrol". Nature. 519 (7543): 370–3. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..370S. doi:10.1038/nature14028. PMC 4368482. PMID 25533949.

- ^ Muthurajan UM, Hepler MR, Hieb AR, Clark NJ, Kramer M, Yao T, Luger K (September 2014). "Automodification switches PARP-1 function from chromatin architectural protein to histone chaperone". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (35): 12752–7. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11112752M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405005111. PMC 4156740. PMID 25136112.

- ^ Soldatenkov VA, Albor A, Patel BK, Dreszer R, Dritschilo A, Notario V (July 1999). "Regulation of the human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase promoter by the ETS transcription factor". Oncogene. 18 (27): 3954–62. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202778. PMID 10435618.

- ^ a b c Chevanne M, Calia C, Zampieri M, Cecchinelli B, Caldini R, Monti D, et al. (June 2007). "Oxidative DNA damage repair and parp 1 and parp 2 expression in Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B lymphocyte cells from young subjects, old subjects, and centenarians". Rejuvenation Research. 10 (2): 191–204. doi:10.1089/rej.2006.0514. PMID 17518695.

- ^ a b Hwang ES, Song SB (2017). "Nicotinamide is an inhibitor of SIRT1 in vitro, but can be a stimulator in cells". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 74 (18): 3347–3362. doi:10.1007/s00018-017-2527-8. PMC 11107671. PMID 28417163. S2CID 25896400.

- ^ Erdélyi K, Bakondi E, Gergely P, Szabó C, Virág L (April 2005). "Pathophysiologic role of oxidative stress-induced poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation: focus on cell death and transcriptional regulation". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 62 (7–8): 751–759. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4506-0. PMC 11924491. PMID 15868400. S2CID 43817844.

- ^ Tanaka Y, Yoshihara K, Tohno Y, Kojima K, Kameoka M, Kamiya T (September 1995). "Inhibition and down-regulation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase results in a marked resistance of HL-60 cells to various apoptosis-inducers". Cellular and Molecular Biology. 41 (6): 771–781. PMID 8535170.

- ^ Rosenthal DS, Ding R, Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Vaillancourt JP, Nicholson DW, Smulson M (May 1997). "Intact cell evidence for the early synthesis, and subsequent late apopain-mediated suppression, of poly(ADP-ribose) during apoptosis". Experimental Cell Research. 232 (2): 313–321. doi:10.1006/excr.1997.3536. PMID 9168807.

- ^ Virág L, Scott GS, Cuzzocrea S, Marmer D, Salzman AL, Szabó C (July 1998). "Peroxynitrite-induced thymocyte apoptosis: the role of caspases and poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase (PARS) activation". Immunology. 94 (3): 345–355. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00534.x. PMC 1364252. PMID 9767416.

- ^ Virág L, Salzman AL, Szabó C (October 1998). "Poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase activation mediates mitochondrial injury during oxidant-induced cell death". Journal of Immunology. 161 (7): 3753–3759. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.161.7.3753. PMID 9759901. S2CID 5734113.

- ^ Virág L, Szabó C (September 2002). "The therapeutic potential of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors". Pharmacological Reviews. 54 (3): 375–429. doi:10.1124/pr.54.3.375. PMID 12223530. S2CID 27100634.

- ^ Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, et al. (July 2002). "Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor". Science. 297 (5579): 259–263. Bibcode:2002Sci...297..259Y. doi:10.1126/science.1072221. PMID 12114629. S2CID 22991897.

- ^ Briggs AG, Bent AF (July 2011). "Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in plants". Trends in Plant Science. 16 (7): 372–80. Bibcode:2011TPS....16..372B. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.008. PMID 21482174.

- ^ Feng B, Liu C, Shan L, He P (December 2016). "Protein ADP-Ribosylation Takes Control in Plant-Bacterium Interactions". PLOS Pathogens. 12 (12) e1005941. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005941. PMC 5131896. PMID 27907213.

- ^ a b Song J, Keppler BD, Wise RR, Bent AF (May 2015). "PARP2 Is the Predominant Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase in Arabidopsis DNA Damage and Immune Responses". PLOS Genetics. 11 (5) e1005200. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005200. PMC 4423837. PMID 25950582.

- ^ a b c Gueven N, Becherel OJ, Kijas AW, Chen P, Howe O, Rudolph JH, et al. (May 2004). "Aprataxin, a novel protein that protects against genotoxic stress". Human Molecular Genetics. 13 (10): 1081–93. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh122. PMID 15044383.

- ^ Morgan HE, Jefferson LS, Wolpert EB, Rannels DE (April 1971). "Regulation of protein synthesis in heart muscle. II. Effect of amino acid levels and insulin on ribosomal aggregation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 246 (7): 2163–70. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77203-2. PMID 5555565.

- ^ Cervellera MN, Sala A (April 2000). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is a B-MYB coactivator". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (14): 10692–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.14.10692. PMID 10744766.

- ^ Hassa PO, Covic M, Hasan S, Imhof R, Hottiger MO (December 2001). "The enzymatic and DNA binding activity of PARP-1 are not required for NF-kappa B coactivator function". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (49): 45588–97. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106528200. PMID 11590148.

- ^ Malanga M, Pleschke JM, Kleczkowska HE, Althaus FR (May 1998). "Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains of p53 and alters its DNA binding functions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (19): 11839–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.19.11839. PMID 9565608.

- ^ a b Dantzer F, Nasheuer HP, Vonesch JL, de Murcia G, Ménissier-de Murcia J (April 1998). "Functional association of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase with DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex: a link between DNA strand break detection and DNA replication". Nucleic Acids Research. 26 (8): 1891–8. doi:10.1093/nar/26.8.1891. PMC 147507. PMID 9518481.

- ^ Masson M, Niedergang C, Schreiber V, Muller S, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G (June 1998). "XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 18 (6): 3563–71. doi:10.1128/MCB.18.6.3563. PMC 108937. PMID 9584196.

- ^ Ku MC, Stewart S, Hata A (November 2003). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 interacts with OAZ and regulates BMP-target genes". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 311 (3): 702–7. Bibcode:2003BBRC..311..702K. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.053. PMID 14623329.

Further reading

[edit]- Rosado MM, Bennici E, Novelli F, Pioli C (August 2013). "Beyond DNA repair, the immunological role of PARP-1 and its siblings". Immunology. 139 (4): 428–37. doi:10.1111/imm.12099. PMC 3719060. PMID 23489378. Review of the subject.