Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

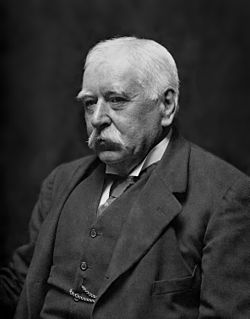

Patrick Manson

View on Wikipedia

Sir Patrick Manson GCMG FRS (3 October 1844 – 9 April 1922) was a Scottish physician who made important discoveries in parasitology, and was a founder of the field of tropical medicine.

Key Information

He graduated from the University of Aberdeen with degrees in Master of Surgery, Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Law. His medical career spanned mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and London. He discovered that filariasis in humans is transmitted by mosquitoes. This is the foundation of modern tropical medicine, and he is recognized with an epithet "Father of Tropical Medicine". This also made him the first person to show pathogen transmission by a blood-feeding arthropod.[1] His discovery directly invoked the mosquito-malaria theory, which became the foundation in malariology. He eventually became the first President of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He founded the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (subsequently absorbed into the University of Hong Kong) and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.[2][3][4]

Manson was inflicted with gout during his service in China.[5] His recurring condition worsened with age. He died in 1922.[6]

Childhood and education

[edit]

Patrick Manson was a son of Alexander Manson and Elizabeth Livingstone Blaikie, born at Oldmeldrum, eighteen miles north of Aberdeen. His father was manager of the local branch of the British Linen Bank and Laird of Fingask. His mother was distant relative of the famed Christian missionary-explorer David Livingstone. He was the second son of a family of three boys and four girls. He developed a childhood passion in natural history, fishing, shooting, carpentry, mechanics and cricket. Among his Presbyterian-Christian family, he showed excellent memory for memorising church sermons at the age of five years.[5]

In 1857 his family moved to Aberdeen, where he entered Gymnasium School. He later continued at West End Academy. In 1859 he was apprenticed to Blaikie Brothers, ironmasters based in Aberdeen. However, he was struck by a type of tuberculosis called Pott's disease of the spine which forced him to take rest. In 1860 he entered the University of Aberdeen from where he completed medicine course in 1865. He was only nineteen and was underage for graduation, so he visited hospitals, museums and medical schools in London. Finally of age he formally graduated in October 1865, and was appointed Medical Officer at Durham Lunatic Asylum, where he worked for seven months.[7] He performed 17 postmortem dissections on patients with psychiatric illnesses for his thesis. In 1866 he received the degrees of Master of Surgery, Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Law.[8]

In China

[edit]

Patrick Manson was inspired by his elder brother, David Manson, who worked in Shanghai in medical service, to join medical officer post in the Customs Service of Formosa (now Taiwan). Manson traveled to Formosa in 1866 as a medical officer to the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs, where he started a long career in the research of tropical medicine. His official daily duty involved inspecting ships docked at the port, check their crews and keep the meteorological record. He also attended to Chinese patients in a local missionary hospital where he was exposed to a wide variety of tropical diseases for his postgraduate training without any supervision. His only research tool was a combination of clinical skill, hand lens and good record keeping. He was in good terms with the native Chinese, learning Mandarin and befriending them. However, due to political conflict between China and Japan over the occupation of the island, he was advised by the British Consul to leave. After 5 years in Formosa, he was transferred to Amoy, on the Chinese coast where he worked for another 13 years. Once again he again served the local Chinese patients at the Baptist Missionary Society's Hospital and Dispensary for the Chinese. His brother David joined him for 2 years.[5][9][10]

Discovery

[edit]He spent his early years researching filaria (a small worm that causes elephantiasis). Manson focused his time on searching for filaria in blood taken from his patients. From this he began to work out the life cycle of filaria and through painstaking observation discovered that the worms were only present in the blood during the night and were absent during the day.

He conducted experiments on his gardener, Hin Lo, who was infected with filaria. He would get mosquitoes to feed on his blood while he slept and then dissect the mosquitoes filled with Hin Lo's blood. "I shall not easily forget the first mosquito I dissected. I tore off its abdomen and succeeded in expressing the blood the stomach contained. Placing this under the microscope, I was gratified to find that, so far from killing the Filaria, the digestive juices of the mosquito seemed to have stimulated it to fresh activity."

Manson observed that filaria only developed as far as an embryo within the human blood and that the mosquito must have a role in the life cycle. Through these early experiments he started to hypothesise about the role of mosquitoes and the spread of disease. That the mosquito (Culex fatigans, now Culex quinquefasciatus) was the intermediate host of the filarial parasite (Wuchereria bancrofti) was a medical breakthrough in 1877. His experimental results were published in the China Customs Medical Report in 1878, and relayed by Spencer Cobbold to the Linnean Society in London.[6]

Out of this arose the mosquito-malaria theory, which suggested that the agent that causes malaria was also spread by a mosquito. In the British Medical Journal in 1894 he published 'On the Nature and Significance of The Crescentic and Flagellated bodies in Malarial Blood'.[11] In this article he states, "the mosquito, having been shown to be the agent by which the filaria is removed from the human blood vessels, this or similar suctorial agent must be the agent which removes from the human blood vessels those forms of the malaria organism which are destined to continue the existence of this organism outside the body." He then proposes, "the hypothesis I have ventured to formulate seems so well grounded that I for one, did circumstances permit, would approach its experimental demonstration with confidence. The necessary experiments cannot for obvious reasons be carried out in England, but I would commend my hypothesis to the attention of medical men in India and elsewhere, where malarial patients and suctorial insects abound." Sir Ronald Ross approached Manson in London and went on to prove this theory. The subsequent correspondence between Ross and Manson is documented as one of the most legendary collaborations in the history of medicine.

Manson's theory was finally proved by Ross in 1898 who described the full life cycle of the malarial parasite (of birds) inside the female mosquito. Ross won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for this discovery. Both Manson and Laveran were also nominated for the Nobel prize. During his acceptance speech, Ross controversially did not acknowledge Manson as his primary mentor. The subsequent fall out between these two great men is well documented in the book The Beast in the Mosquito: The Correspondence of Ronald Ross and Patrick Manson.[12]

Manson also demonstrated a new species of Schistosoma (Bilharzia) known as Schistosoma mansoni.[7][9][13] In 1882, he discovered sparganosis, a parasitic infection caused by the tapeworm Spirometra.[14][15]

In Hong Kong

[edit]From 1883 to 1889, Manson worked in Hong Kong. He was the first to import cows from his native Scotland to Hong Kong and thus establish a dairy farm in Pok Fu Lam in 1885 and the company Dairy Farm in Hong Kong. However his most significant works are in medical education. He was the founder of the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, where Sun Yat-sen was one of his first pupils. In 1896, through his contacts at the Foreign Office, Manson managed to secure the release of Sun after he had been kidnapped in London by Chinese officials. Sun went on to become the first President of the Republic of China. In 1911 Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese became the University of Hong Kong.[5][6]

In London

[edit]After 23 years in Southeast Asia, Manson had amassed considerable wealth from his medical practices. He returned to London in 1889, and settled at 21 Queen Anne Street, W1. In 1890 he qualified the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians. He became Physician at the Seamen's Hospital Society in 1892 and also Lecturer on Tropical Diseases in St George's Hospital. In July 1897 was appointed Chief Medical Officer to the Colonial Office. It was here that he used his influence to push for the foundation of a School of Tropical Medicine at the Albert Dock Seamen's Hospital.

In a speech in 1897, he endorsed a call by fellow Scottish physician Andrew Davidson for courses in tropical medicine at every British medical school.[16] The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine was opened on 2 October 1899. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the 1900 New Year Honours list on 1 January 1900,[17][18] and was invested by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle on 1 March 1900.[19] Manson was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh in this year. He retired from the Colonial Office in 1912.[7]

Honours and recognitions

[edit]- Elected Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1895

- Elected to the Royal Society in 1900.

- Elected President of the Epidemiological Society in 1900.

- Awarded the Fothergill medal in 1902.

- Knighted KCMG in 1903 and GCMG in 1912.

- Awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science by the University of Oxford in 1904.

- Awarded the Bisset Hawkins Medal by the Royal College of Physicians in 1905

- First president of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 1907.

- Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine (1912).[20]

- The Manson Medal is awarded triennially by the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.[21]

- A human trematode parasite Schistosoma mansoni is named in his honour.[22]

- Tapeworm species, Spirometra (Sparganum) mansoni and S. mansonoides are named after him.[15]

- A genus of mosquito Mansonia, species of which are vectors of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis and Brugian filariasis, is named after him.[23]

- A genus of filarial roundworm Mansonella was named after him in 1891.[24]

Family

[edit]In 1876, he married Henrietta Isabella Thurbun, with whom he had three sons and one daughter.

His daughter Edith Margaret Manson (1879–1948) married Philip Henry Bahr, one of Manson's pupils at the London School of Tropical medicine. Sir Philip Manson-Bahr CMG DSO MD FRCP (Lond) (1881–1966) became a leader in the field of tropical medicine in his own right.

In 1995 Manson's grandson, Dr (Philip Edmund) Clinton Manson-Bahr (1911–1996) won the Manson Medal. It is the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine's highest mark of distinction for contributions to tropical medicine, and is awarded triennially.

Manson's great-grandson Dr Gordon Manson-Bahr was a GP in Norfolk, UK for most of his medical career and his great-great grandson Dr David Manson-Bahr is a urologist in London.

Manson's grandfather (John Manson of Kilblean 1762–1838) and his great-uncle (Alexander Manson b. 1778) founded the Glen Garioch Whisky distillery in 1797, which still operates in Oldmeldrum to this day.

'Manson Road' in Oldmeldrum was named in his honour.

Death

[edit]

He died on 9 April 1922 after having a heart attack.[7] Following a memorial service at St Paul's Cathedral in London, he was buried in Allenvale cemetery in Aberdeen.[7]

Publications

[edit]- Manson's Tropical Diseases : a Manual of the Diseases of Warm Climates (1898);[25] 7th edition. Cassell. 1921.

- Lectures on Tropical Diseases (1905);

- Diet in the Diseases of Hot Climates (1908), with Charles Wilberforce Daniels (1862–1927).

References

[edit]- ^ Mullen, Gary Richard; Durden, Lance A. (2019). Medical and veterinary entomology (3rd ed.). London: Academic press, an imprint of Elsevier. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-12-814043-7.

- ^ Manson-Bahr, Patrick (1962). Patrick Manson. The Father of Tropical Medicine. Thomas Nelson.

- ^ Eli Chernin (1983). "Sir Patrick Manson: An Annotated Bibliography and a Note on a Collected Set of His Writings". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 15 (2): 353–386. JSTOR 4453015.

- ^ J. W. W. Stephens (2004). "Manson, Sir Patrick (1844–1922)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34865. Retrieved 3 February 2014. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d To, Kelvin KW; Yuen, Kwok-Yung (2012). "In memory of Patrick Manson, founding father of tropical medicine and the discovery of vector-borne infections". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 1 (10): e31. doi:10.1038/emi.2012.32. PMC 3630944. PMID 26038403.

- ^ a b c Jay, V (2000). "Sir Patrick Manson. Father of tropical medicine". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 124 (11): 1594–5. doi:10.5858/2000-124-1594-SPM. PMID 11079007.

- ^ a b c d e Cook, G.C. (2007). Tropical Medicine: an Illustrated History of The Pioneers. Burlington: Elsevier. pp. 51–66. ISBN 9780080559391.

- ^ "Patrick Manson". AboutAberdeen.com. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Patrick Manson Biography (1884–1922)". www.faqs.org. Advameg, Inc. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Han Cheung (7 April 2024). "Taiwan in Time: A medical pioneer's fledgling days in Formosa". Taipei Times. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ Manson, P (1894). "On the Nature and Significance of The Crescentic and Flagellated bodies in Malarial Blood". BMJ. 2 (1771): 1306–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1771.1306. PMC 2405325. PMID 20755205.

- ^ The Beast in the Mosquito: The Correspondence of Ronald Ross and Patrick Manson. Edited by William F. Bynum, Caroline Overy (Cilo Media 51, 1998 ISBN 90-420-0721-4)

- ^ Chernin, E (1983). "Sir Patrick Manson's studies on the transmission and biology of filariasis". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 148–66. doi:10.1093/clinids/5.1.148. PMID 6131527.

- ^ Lescano, Andres G; Zunt, Joseph (2013). "Other cestodes". Neuroparasitology and Tropical Neurology. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 114. pp. 335–345. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53490-3.00027-3. ISBN 9780444534903. PMC 4080899. PMID 23829923.

- ^ a b Yan, Chen; Ye, Bin (2013). "Sparganosis in China". In Mehlhorn, Heinz; Wu, Zhongdao; Ye, Bin (eds.). Treatment of Human Parasitosis in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39824-7_11. ISBN 978-3-642-39823-0.(subscription required)

- ^ Manson, P. (1897). The Necessity For Special Education In Tropical Medicine. The British Medical Journal, 2(1919), 985-989. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20251585

- ^ "New Year Honours". The Times. No. 36027. London. 1 January 1900. p. 9.

- ^ "No. 27150". The London Gazette. 2 January 1900. p. 2.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36079. London. 2 March 1900. p. 6.

- ^ Hunting, Penelope (2002). "7. The first sections at the Society". The History of The Royal Society of Medicine. Royal Society of Medicine Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 1-85315-497-0.

- ^ "Manson Medal". Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Birch, CA (1974). "Schistosoma mansoni. Sir Patrick Manson, 1844–1922". The Practitioner. 213 (1277): 730–2. PMID 4156405.

- ^ Mehlhorn, Heinz (2008). "Mansonia". Encyclopedia of Parasitology (3 ed.). Berlin: Springer. pp. 776–778. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-48996-2_1853. ISBN 978-3-540-48994-8.

- ^ Mehlhorn, Heinz (2008). "Mansonella". Encyclopedia of Parasitology. pp. 776–778. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-48996-2_1852. ISBN 978-3-540-48994-8.

- ^ Patrick Manson. Tropical Diseases: A Manual of the Diseases of Warm Climates, pp 635, 12 mo, Illustrated by 88 wood engravings and two colored plates. New York, William Wood & Company. 1898 (See also: JAMA. 1898; XXXI(8):428. doi:10.1001/jama.1898.02450080054027)

External links

[edit]- Dairy Farm Group

- University of Hong Kong Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine

- Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- Wellcome Trust Images

- Wellcome Trust Library

- Biography at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Biography at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

- Undiscovered Scotland: The Ultimate Online Guide

- Works by Patrick Manson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Patrick Manson

View on GrokipediaSir Patrick Manson (3 October 1844 – 9 April 1922) was a Scottish physician and parasitologist who founded the discipline of tropical medicine through pioneering research on vector-borne diseases.[1][2] While serving as a medical officer in China from 1866 to 1889, Manson conducted experiments demonstrating that mosquitoes act as intermediate hosts for the filarial parasites responsible for lymphatic filariasis in humans, marking the first identification of an arthropod vector in human disease transmission.[2][3] This discovery, achieved through dissection of mosquitoes fed on infected patients, established a causal mechanism linking insect vectors to tropical pathologies and inspired subsequent work, including Ronald Ross's proof of mosquito transmission of malaria.[4] Returning to London, Manson advocated for specialized training in tropical diseases, leading to the establishment of the London School of Tropical Medicine in 1899 under his direction, an institution that trained practitioners to combat colonial-era health challenges in tropical regions.[5] His empirical approach emphasized direct observation and experimentation over prevailing miasmatic theories, earning him knighthoods and recognition as a foundational figure in parasitology despite limited formal mentorship in the emerging field.[6][7]