Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spherical astronomy

View on Wikipedia

Spherical astronomy, or positional astronomy, is a branch of observational astronomy used to locate astronomical objects on the celestial sphere, as seen at a particular date, time, and location on Earth. It relies on the mathematical methods of spherical trigonometry and the measurements of astrometry.

This is the oldest branch of astronomy and dates back to antiquity. Observations of celestial objects have been, and continue to be, important for religious and astrological purposes, as well as for timekeeping and navigation. The science of actually measuring positions of celestial objects in the sky is known as astrometry.

The primary elements of spherical astronomy are celestial coordinate systems and time. The coordinates of objects on the sky are listed using the equatorial coordinate system, which is based on the projection of Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere. The position of an object in this system is given in terms of right ascension (α) and declination (δ). The latitude and local time can then be used to derive the position of the object in the horizontal coordinate system, consisting of the altitude and azimuth.

The coordinates of celestial objects such as stars and galaxies are tabulated in a star catalog, which gives the position for a particular year. However, the combined effects of axial precession and nutation will cause the coordinates to change slightly over time. The effects of these changes in Earth's motion are compensated by the periodic publication of revised catalogs.

To determine the position of the Sun and planets, an astronomical ephemeris (a table of values that gives the positions of astronomical objects in the sky at a given time) is used, which can then be converted into suitable real-world coordinates.

The unaided human eye can perceive about 6,000 stars, of which about half are below the horizon at any one time. On modern star charts, the celestial sphere is divided into 88 constellations. Every star lies within a constellation. Constellations are useful for navigation. Polaris lies nearly due north to an observer in the Northern Hemisphere. This pole star is always at a position nearly directly above the North Pole.

Positional phenomena

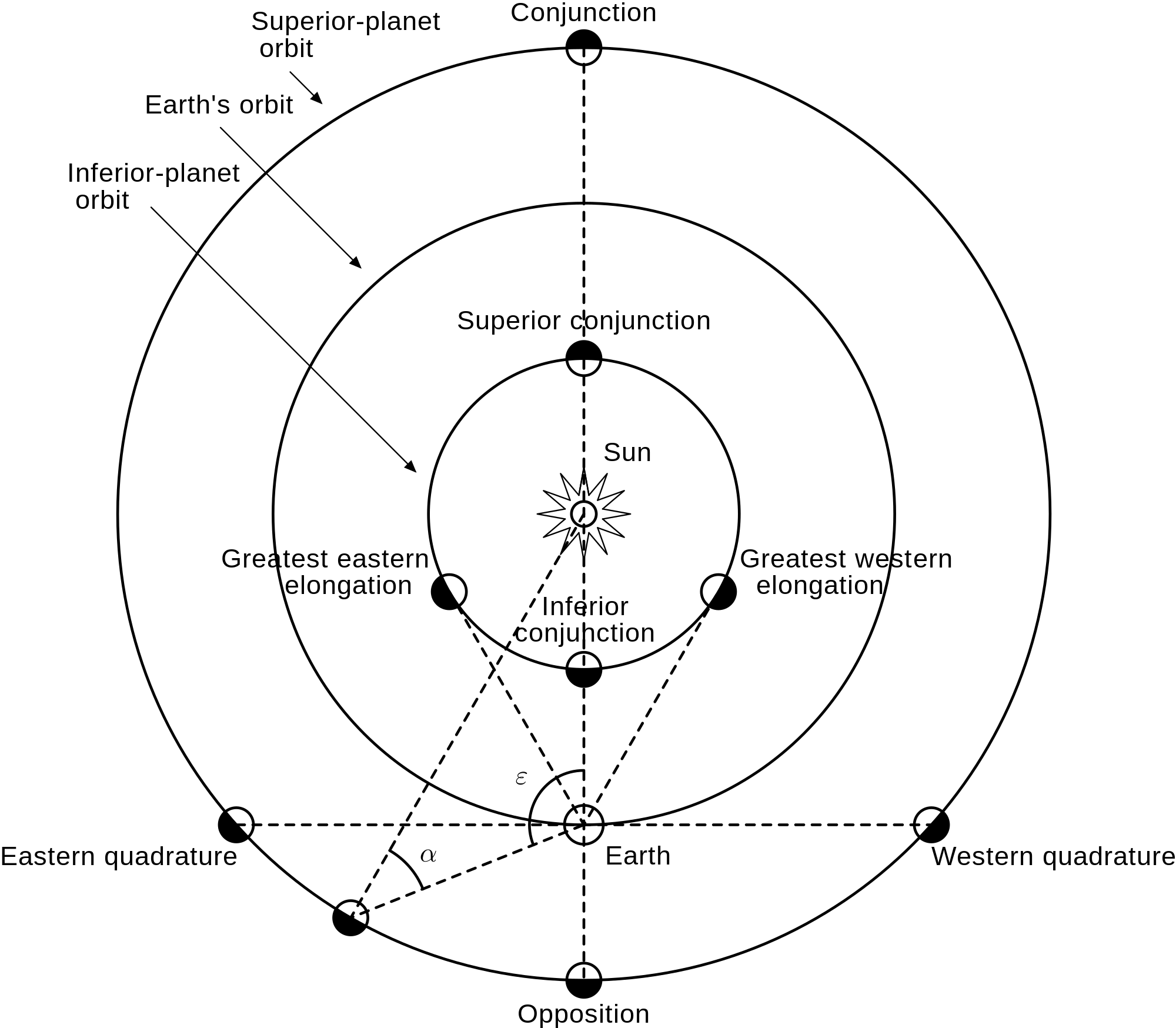

[edit]- Planets which are in conjunction form a line which passes through the center of the Solar System.

- The ecliptic is the plane which contains the orbit of a planet, usually in reference to Earth.

- Elongation refers to the angle formed by a planet, with respect to the system's center and a viewing point.

- A quadrature occurs when the position of a body (moon or planet) is such that its elongation is 90° or 270°; i.e. the body-earth-sun angle is 90°

- Superior planets have a larger orbit than Earth's, while the inferior planets (Mercury and Venus) orbit the Sun inside Earth's orbit.

- A transit may occur when an inferior planet passes through a point of conjunction.

Ancient structures associated with positional astronomy include

[edit]See also

[edit]- Astrological aspects

- Astrogeodesy

- Astrometry

- Celestial coordinate system

- Celestial mechanics

- Celestial navigation

- Diurnal motion

- Eclipse

- Ecliptic

- Elongation

- Epoch

- Equinox

- Halley, Edmond

- History of Astronomy

- Jyotish

- Kepler's laws of planetary motion

- Occultation

- Parallax

- Retrograde and prograde motion

- Sidereal time

- Solstice

References

[edit]- Robin M. Green, Spherical Astronomy, 1985, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31779-7

- William M. Smart, edited by Robin M. Green, Textbook on Spherical Astronomy, 1977, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29180-1. (This classic text has been re-issued)

External links

[edit]- Software

- NOVAS is an integrated package of subroutines for the computation of a wide variety of common astrometric quantities and transformations, in Fortran and C, from the U.S. Naval Observatory.

- jNOVAS is a java wrapper for library developed and distributed by The United States Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command (NMOC) with included JPL planetary and lunar ephemeris DE421 binary file published by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- Course notes and tutorials