Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Province of Saxony

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

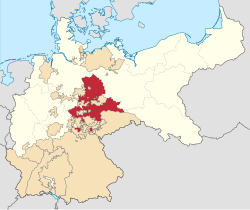

The Province of Saxony (German: Provinz Sachsen), also known as Prussian Saxony (Preußisches Sachsen), was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia and later the Free State of Prussia from 1816 until 1944. Its capital was Magdeburg.

Key Information

It was formed by the merger of various territories ceded or returned to Prussia in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna: most of the former northern territories of the Kingdom of Saxony (the remainder of which became part of Brandenburg or Silesia), the former French Principality of Erfurt, the Duchy of Magdeburg, the Altmark, the Principality of Halberstadt, and some other districts.

The province was bounded by the Electorate of Hesse (the province of Hesse-Nassau after 1866), the Kingdom of Hanover (the province of Hanover after 1866) and the Duchy of Brunswick to the west, Hanover (again) to the north, Brandenburg to the north and east, Silesia to the south-east, and the rump kingdom of Saxony and the small Ernestine duchies to the south. Its shape was very irregular and it entirely surrounded enclaves of Brunswick and some of the Ernestine duchies. It also possessed several exclaves, and was almost entirely bisected by the Duchy of Anhalt save for a small corridor of land around Aschersleben (which itself bisected Anhalt). The river Havel ran along the north-eastern border with Brandenburg north of Plaue but did not follow the border exactly.

The majority of the population was Protestant, with a Catholic minority (about 8% as of 1905) considered part of the diocese of Paderborn. The province sent 20 members to the Reichstag and 38 delegates to the Prussian House of Representatives (Abgeordnetenhaus).

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The province was created in 1816 out of the following territories:

- the Prussian lands which lay immediately to the (south-)west of the Havel river; those which lay beyond the Elbe – the Altmark, Principality of Halberstadt and County of Wernigerode and the western part of the Duchy of Magdeburg – had been part of the Kingdom of Westphalia from 1807 to 1813 but had since been regained

- territory gained from the Kingdom of Saxony after the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 (confirmed in 1815): the towns and surrounding territories of Wittenberg, Merseburg, Naumburg, Mansfeld, Querfurt, and Henneberg; within the Kingdom of Saxony these had comprised:

- most of the Wittenberg Circle (excluding the far north around Belzig which was merged into Brandenburg)

- the northern parts of the Meissen and Leipzig Circles

- the Thuringia Circle

- a small part of the Neustadt Circle around Ziegenrück, which formed an exclave within Thuringia

- the County of Stolberg-Stolberg

- the Saxon parts of the former County of Mansfeld (the remainder had been part of Magdeburg)

- part of the Principality of Querfurt

- most of the Saxon portion of the former County of Henneberg around Suhl, which formed a second Thuringian exclave

- the former bishoprics of Merseburg and Naumburg

- the County of Barby;

- territory given to Prussia after the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss: lands around Erfurt (formerly directly subordinate to the Emperor of the French as the Principality of Erfurt), the Eichsfeld (formerly belonging to the Archbishopric of Mainz), the former imperial cities of Mühlhausen and Nordhausen, and Quedlinburg Abbey.

- several small territories which were former Hannovarian enclaves within the Altmark, centred around Klötze, and which had been part of the Kingdom of Westphalia from 1807 to 1813

- a small amount of territory on the left bank of the Havel that had previously belonged to Anhalt-Dessau (Anhalt-Zerbst before 1796)

Later history

[edit]

The Province of Saxony was one of the richest regions of Prussia, with highly developed agriculture and industry. In 1932, the province was enlarged with the addition of the regions around Ilfeld and Elbingerode, which had previously been part of the Province of Hanover.

On 1 July 1944, the Province of Saxony was divided along the lines of its three administrative regions. The Erfurt Regierungsbezirk was merged with the Herrschaft Schmalkalden district of the Province of Hesse-Nassau and given to the state of Thuringia. The Magdeburg Regierungsbezirk became the Province of Magdeburg, and the Merseburg Regierungsbezirk became the Province of Halle-Merseburg.

In 1945, the Soviet military administration combined Magdeburg and Halle-Merseburg with the State of Anhalt into the Province of Saxony-Anhalt, with Halle as its capital. The eastern part of the Blankenburg exclave of Brunswick and the Thuringian exclave of Allstedt were also added to Saxony-Anhalt. In 1947, Saxony-Anhalt became a state.

The East German states, including Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt, were abolished in 1952, but they were recreated as part of the reunification of Germany in 1990 (with some slight border changes; in particular territories around Torgau, which were part of Saxony-Anhalt between 1945 and 1952, passed to Saxony) as modern states of Germany.

The borders of the old province of Saxony endured longest in the ecclesiastical sphere, since the Church Province of Saxony in the Evangelical Church remained in existence until 2008.

Subdivisions

[edit]Prior to 1944, the province of Saxony was divided into three Regierungsbezirke. In 1945, only the provinces of Magdeburg and Halle-Merseburg were re-merged.

Regierungsbezirk Magdeburg

[edit]

Urban districts (Stadtkreise)

- Aschersleben (1901–1950)

- Burg bei Magdeburg (1924–1950)

- Halberstadt (1817–1825 and 1891–1950)

- Magdeburg

- Quedlinburg (1911–1950)

- Stendal (1909–1950)

Rural districts (Landkreise)

- Calbe a./S.

- Gardelegen

- Haldensleben

- Jerichow I

- Jerichow II

- Oschersleben (Bode)

- Osterburg

- Quedlinburg

- Salzwedel

- Stendal

- Wanzleben

- Wernigerode

- Wolmirstedt

Regierungsbezirk Merseburg

[edit]Urban districts (Stadtkreise)

- Eisleben (1908–1950)

- Halle a. d. Saale

- Merseburg (1921–1950)

- Naumburg a. d. Saale (1914–1950)

- Weißenfels (1899–1950)

- Wittenberg (Lutherstadt)

- Zeitz (1901–1950)

Rural districts (Landkreise)

- Bitterfeld

- Delitzsch

- Eckartsberga

- Liebenwerda

- Mansfelder Gebirgskreis

- Mansfelder Seekreis

- Merseburg

- Querfurt

- Saalkreis

- Sangerhausen

- Schweinitz

- Torgau

- Weißenfels

- Wittenberg

- Zeitz

Regierungsbezirk Erfurt

[edit]Urban districts (Stadtkreise)

- Erfurt (1816–18 and 1872–present)

- Mühlhausen (1892–1950)

- Nordhausen (1882–1950)

Rural districts (Landkreise)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Handbuch der Provinz Sachsen, Magdeburg, 1900.

- Jacobs, Geschichte der in der preussischen Provinz Sachsen vereinigten Gebiete, Gotha, 1884.

- Die Provinz Sachsen in Wort und Bild, Berlin, 1900 (reprint: Naumburger Verlagsanstalt 1990, ISBN 3-86156-007-0).

External links

[edit]- Further information (in German)

- Administrative subdivision and population breakdown of Saxony province, 1900/1910 (in German)

Province of Saxony

View on GrokipediaThe Province of Saxony was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia established in 1816, formed from territories ceded by the Kingdom of Saxony and other adjacent lands as part of the post-Napoleonic territorial rearrangements at the Congress of Vienna.[1][2] With its capital at Magdeburg, the province encompassed central German regions including the areas around Halle, Erfurt, and Merseburg, serving as a key administrative unit within Prussia through the German Empire, Weimar Republic, and into the Nazi era until its dissolution in 1945.[3] The province's territory, roughly 25,000 square kilometers in extent, featured fertile plains suited to intensive agriculture, particularly grain production and sugar beet cultivation, alongside emerging industrial centers focused on manufacturing and mining.[4] Economically, it ranked among Prussia's wealthiest provinces, with highly developed agrarian and industrial sectors that supported broader German economic integration post-unification in 1871.[4] Administrative divisions included the government districts (Regierungsbezirke) of Magdeburg, Merseburg, and Erfurt, facilitating efficient governance over a population that grew steadily through urbanization and migration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During the interwar period, the Province of Saxony experienced political tensions reflective of Weimar Germany's instability, yet maintained its role as an industrial powerhouse until World War II disruptions. In July 1944, amid wartime administrative reforms, it was subdivided into three Gaue under Nazi control, but following Germany's defeat in 1945, its lands were reorganized into the Soviet-occupied Province of Saxony-Anhalt, later integrated into the German Democratic Republic.[3] This transition marked the end of its Prussian identity, with legacy influences persisting in the modern states of Saxony-Anhalt and parts of Thuringia.

Formation and Administration

Establishment via Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna, held from September 1814 to June 1815, reorganized European territories to restore monarchical legitimacy and balance power after Napoleon's defeat. The Kingdom of Saxony faced territorial losses due to its alliance with France during the wars, with Prussia receiving ceded lands to counter Russian ambitions over Saxony and to consolidate Prussian influence in central Germany. This arrangement was enshrined in the Treaty between Prussia and Saxony of 18 May 1815, which detailed the boundary line separating retained and ceded Saxon districts, and was integrated into the Congress's Final Act signed on 9 June 1815.[5][6] The ceded Saxon territories encompassed roughly two-fifths of the kingdom's pre-war area, including northern districts along the Elbe River such as Wittenberg, Torgau, Eilenburg, Delitzsch, and Merseburg, bounded by lines from the Bohemian frontier near Wiese, along the Wittich and Neisse rivers, and through specified villages and bailiwicks.[5][7] These were combined with Prussian holdings recovered from Napoleonic occupation, notably the Duchy of Magdeburg and Principality of Halberstadt (annexed by the French-backed Kingdom of Westphalia in 1807 and regained post-1813), the Altmark and Mittelmark regions of Brandenburg, and former imperial enclaves like the Principality of Erfurt, Eichsfeld (ex-Archbishopric of Mainz), and free cities Mühlhausen and Nordhausen.[4] In 1816, King Frederick William III of Prussia formalized these territories into the Province of Saxony (Provinz Sachsen), with Magdeburg designated as the administrative capital, marking its integration as the ninth province of the Kingdom of Prussia.[8] This creation emphasized Prussian strategic consolidation, linking fragmented lands into a unified entity for efficient taxation, conscription, and governance under the post-Napoleonic reforms.[4]Governmental Structure and Prussian Integration

The Province of Saxony was formally established on April 1, 1816, as part of Prussia's post-Napoleonic territorial reorganization, integrating lands ceded by the Kingdom of Saxony at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, including northern Saxon territories, alongside preexisting Prussian holdings such as the Duchy of Magdeburg, the Principality of Halberstadt, the County of Mansfeld, and the Thuringian principalities around Erfurt.[8][4] Prussian military administration had been imposed on the annexed Saxon districts as early as June 5, 1815, facilitating a swift transition to centralized control and suppressing local Saxon institutions.[3] Governance followed the Prussian provincial model, emphasizing bureaucratic hierarchy and obedience to Berlin, with the Oberpräsident—appointed directly by the King of Prussia—serving as the senior civil authority in Magdeburg, the provincial capital.[9] The Oberpräsident coordinated with the Ministry of the Interior, enforced royal policies on taxation, conscription, and infrastructure, and supervised subordinate officials, ensuring alignment with Prussian absolutist principles until the constitutional reforms of 1848–1850.[8] The province was subdivided into three Regierungsbezirke (government districts)—Erfurt, Magdeburg, and Merseburg—established during the Prussian reforms of 1808–1816 to decentralize routine administration while maintaining oversight.[10] Each bezirk was led by a Regierungspräsident, who managed district-level affairs including public order, education, and economic regulation, reporting to the Oberpräsident.[11] Further subdivision occurred at the Kreis (district) level, where appointed Landräte handled local implementation of policies, such as land management and poor relief, underscoring the system's reliance on career civil servants over elected bodies.[9] This structure reflected Prussia's causal emphasis on efficient, top-down administration to foster loyalty and modernization, contrasting with the more fragmented Saxon governance it replaced, though it faced resistance from former Saxon elites until assimilation through appointments and economic incentives.[3]Administrative Subdivisions

The Province of Saxony was subdivided into three Regierungsbezirke (government districts)—Magdeburg, Merseburg, and Erfurt—established in 1816 as part of the Prussian administrative reorganization following the Congress of Vienna.[3] These districts functioned as regional administrative units overseeing local governance, taxation, and policing, with each headed by a Regierungspräsident appointed by the Prussian state.[12] Each Regierungsbezirk was further divided into Kreise (districts), comprising independent urban Stadtkreise (such as Magdeburg and Halle) and rural Landkreise, which in turn encompassed Gemeinden (municipalities) as the basic local units. By 1900, the province totaled 51 Kreise: Regierungsbezirk Magdeburg included 3 Stadtkreise and 14 Landkreise across 11,512.87 km² with 1,176,372 inhabitants; Regierungsbezirk Merseburg had 3 Stadtkreise and 16 Landkreise over 10,210.81 km² and 1,189,825 inhabitants; and Regierungsbezirk Erfurt comprised 3 Stadtkreise and 9 Landkreise in 3,531.61 km² with 466,419 inhabitants.[12] This structure remained largely stable until 1944, when a decree by Adolf Hitler reorganized the province by detaching Regierungsbezirke Magdeburg and Merseburg into new provinces named Magdeburg and Halle-Merseburg, while assigning Regierungsbezirk Erfurt to Thuringia; the changes took effect on 1 July 1944 but were rendered moot by the Soviet occupation in 1945.[13]Geography and Resources

Territorial Extent and Borders

The Province of Saxony occupied approximately 25,318 square kilometers in central Germany, primarily along the middle Elbe River valley, as documented in historical geographic surveys from the early 19th century.[14] This area remained largely stable from its establishment in 1816 until its dissolution in 1945, encompassing fertile plains, the Harz Mountains in the west, and rolling hills in the south.[8] The province's extent included the Prussian Altmark region north of the Elbe, the districts around Magdeburg and Halle, and the Erfurt enclave in former Thuringian territories.[12] Its borders were defined by neighboring Prussian provinces and German states: to the north, the Province of Brandenburg and the Kingdom of Hanover; to the east, Brandenburg; to the south, the Kingdom of Saxony and smaller Thuringian entities like Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach; and to the west, Hanover, the Duchy of Brunswick, and the Anhalt principalities.[14][15] These boundaries, established post-Congress of Vienna, reflected Prussia's consolidation of fragmented Saxon and Napoleonic-era territories, with minimal alterations until the 20th century.[8] By 1939, the province's area had slightly expanded to 25,529 square kilometers due to administrative adjustments under the Nazi regime.[12]Physical Geography and Natural Resources

The Province of Saxony encompassed approximately 9,750 square miles of predominantly flat terrain within the North German Plain, transitioning to hilly landscapes in the west and southwest where it included foothills of the Harz Mountains, with the Brocken peak reaching 3,417 feet.[16][17] The region featured fertile loess soils in areas such as the Magdeburg Börde and Goldene Aue, recognized as among Germany's most productive due to their siltlike composition superior to typical German soils, while northern Altmark plains were sandier and less fertile.[16][18] Major rivers draining the province belonged primarily to the Elbe basin, including the Saale, Unstrut, and Mulde, which supported agriculture through irrigation and valley pastures; a minor western district contributed to the Weser system.[16][17] Unique saltwater lakes existed between Halle and Eisleben, the only such features in Prussia.[16] The climate was temperate continental, conducive to intensive farming. Natural resources centered on agriculture, with 61% of land arable, yielding exports of wheat and rye alongside substantial beetroot sugar production exceeding 400,000 tons in 1883–1884, flax, hops, and oilseeds; livestock included over 624,000 cattle and 1.39 million sheep in 1883.[16][17] Mineral wealth featured salt from mines at Stassfurt, Schönebeck, and Halle (256,000 tons in 1883–1884), brown coal (lignite) from deposits between Oschersleben and Weißenfels yielding about 8 million tons annually, copper accounting for 75% of Germany's output mainly from the Harz, and silver comprising one-third of the national yield, plus pyrites, alum, plaster, sulphur, and alabaster.[16][17] Forests covered roughly 21% of the area, concentrated in the Harz and hills but overall timber-poor.[17]Demographics

Population Growth and Distribution

The population of the Province of Saxony at its formation in 1816 stood at 1,197,053 inhabitants, increasing to 1,792,033 by 1850 amid initial Prussian reforms that enhanced agricultural productivity and internal migration.[19] By 1871, following territorial stability post-unification, it reached 2,103,000, and expanded further to 2,832,616 in 1900 and 3,089,000 by the 1910 census, reflecting sustained natural growth supplemented by inflows from rural areas and neighboring regions drawn to emerging industries.[20] [19] This expansion aligned with a rising density from 83 inhabitants per square kilometer in 1871 to 122 by 1910, exceeding the Prussian average due to the province's central location and resource base.[21] Population distribution favored urban and peri-urban zones, with roughly 42.9% residing in settlements exceeding 10,000 inhabitants by 1910, up from earlier rural dominance, as migration fueled growth in manufacturing hubs.[22] Major concentrations occurred in the administrative districts of Magdeburg and Merseburg, where cities like Magdeburg (the capital) and Halle developed as focal points for trade, chemicals, and machinery production, while Erfurt in the southwest anchored smaller-scale commerce and agriculture. Rural dispersal prevailed across the Magdeburg Börde and Harz foothills, sustaining a agrarian workforce that comprised the majority until the late 19th century, though overall urbanization accelerated post-1871 amid railway expansion and labor demands.[22]Ethnic, Linguistic, and Religious Composition

The population of the Province of Saxony was ethnically homogeneous, consisting almost entirely of Germans descended from medieval Saxon, Thuringian, and Franconian settlers, with no significant non-German ethnic minorities documented in 19th- or early 20th-century censuses or administrative records.[8] Unlike eastern Prussian provinces with Polish or Lithuanian populations, or Lusatian areas with Sorbs, the province's central location and long history of Germanic settlement resulted in negligible Slavic or other foreign elements by the Prussian era.[8] Linguistically, German was the sole vernacular, spoken universally as a Central German dialect continuum encompassing Thuringian-Upper Saxon varieties, which featured phonetic shifts like the High German consonant change but retained Middle German traits such as softened consonants and vowel mergers distinct from northern Low German or southern High German forms.[23] Imperial censuses from 1905 and 1910, which tracked mother tongues in Prussia, recorded no meaningful non-German linguistic groups in the province, reflecting centuries of assimilation following the Ostsiedlung migrations.[24] Religiously, the province was overwhelmingly Protestant, aligned with the Prussian Union of Churches established in 1817, which merged Lutheran and Reformed traditions under state oversight. The 1871 census recorded 1,966,696 Protestants (approximately 94% of the population) and 126,735 Catholics (about 6%), with Jews and other denominations comprising less than 1%.[25] This Protestant dominance stemmed from the Reformation's deep roots in the region, including Martin Luther's activities in nearby electoral Saxony, though Catholic pockets persisted in areas like Erfurt due to historical bishoprics; patterns remained stable through the 1900 census, with Protestants exceeding 90% amid minimal Jewish communities (around 10,000-15,000 individuals province-wide).[25][26]Historical Development

Early Prussian Reforms and Economic Modernization (1816–1871)

Following its establishment in 1816, the Province of Saxony was integrated into the Prussian administrative framework through the provincial reorganization ordinance of 30 April 1815, which divided the kingdom into ten provinces each governed by an Oberpräsident to ensure centralized control and uniform policy implementation.[27] This structure extended the core Prussian reforms of the Stein-Hardenberg era, including municipal self-administration laws from 1808 and 1831 that devolved limited powers to local councils, promoting fiscal responsibility and infrastructure maintenance without undermining monarchical authority.[28] Legal unification advanced via the Allgemeines Landrecht's application and subsequent codes, reducing jurisdictional fragmentation inherited from Saxon principalities and facilitating bureaucratic efficiency.[29] Agrarian reforms, rooted in the 1807 October Edict abolishing serfdom, were systematically enforced in the province's eastern estates, compelling nobles to compensate peasants for labor services and enabling land sales that consolidated holdings into viable commercial farms by the 1840s.[30] Full redemption of feudal dues occurred under the 1850 regulation, freeing labor for non-agricultural pursuits and boosting productivity in the Magdeburg Börde's black earth soils through mechanized plowing and beet sugar processing, which expanded output to supply Prussian distilleries and refineries.[30] These measures aligned with causal incentives for investment, as property rights clarification reduced uncertainty and spurred enclosure-like rationalization, though large Junker domains retained dominance over smallholders, preserving social hierarchies amid rising yields.[31] Economic modernization accelerated with the province's inclusion in the Zollverein customs union from 1834, which dismantled internal barriers and integrated Saxony's Elbe River ports like Magdeburg into a tariff-protected market, fostering exports of grain, timber, and early manufactures to core Prussian industrial zones.[32] Railway expansion from the 1840s onward, including lines linking Magdeburg to Berlin and Halle, reduced transport costs by up to 50% for bulk goods, spurring urban growth and industrial clustering; districts with rail access experienced 1-2% higher annual population and output expansion through enhanced market access and labor mobility.[33] In Magdeburg and Halle, this infrastructure supported nascent sectors like machinery forging and potash extraction, with the former city's foundries producing steam engines by 1850, capitalizing on waterway linkages to downstream markets while agricultural surpluses funded initial capital accumulation.[34] By the 1860s, these reforms had positioned the province as a transitional hub between agrarian east and industrial west, with per capita income growth outpacing stagnant Austrian counterparts due to Prussian fiscal discipline and infrastructure primacy, though unevenly distributed favoring urban and estate elites.[35] The absence of revolutionary disruptions post-1848, unlike in fragmented southern states, preserved reform momentum, culminating in the province's pivotal logistics role during the 1866 Austro-Prussian War and 1870-71 Franco-Prussian conflict, where mobilized railways expedited troop and supply movements.[33] This integration underscored causal links between institutional continuity, transport innovation, and aggregate efficiency gains, embedding Saxony within Prussia's unification trajectory.[32]Role in German Unification and Imperial Era (1871–1918)

The Province of Saxony, as a core territory of the Kingdom of Prussia, played an integral part in the events leading to German unification in 1871. Prussian forces, including contingents recruited from the province, mobilized rapidly following the declaration of war by France on July 19, 1870. The IV Army Corps, headquartered in Magdeburg within the province, formed a key component of the Prussian order of battle, participating in operations that encircled French armies and secured decisive victories such as the Battle of Sedan on September 2, 1870. This military success facilitated the proclamation of the German Empire on January 18, 1871, at Versailles, with King Wilhelm I of Prussia assuming the imperial throne.[36] Within the newly formed German Empire, the Province of Saxony remained under Prussian administration, contributing to the centralized structure dominated by Prussian institutions. The province's Oberpräsident oversaw local governance, while its districts elected representatives to the Prussian Landtag and the imperial Reichstag, reflecting a blend of conservative Junker influence in rural areas and emerging liberal and social democratic sentiments in urban centers like Magdeburg and Halle. Economically, the province supported imperial growth through its agricultural output, particularly grain and sugar beets, which fueled food supplies and processing industries; by 1900, sugar production in the region exceeded 500,000 tons annually, bolstering Germany's export economy. Industrial development included machinery manufacturing in Magdeburg and early chemical processing around Halle, aligning with the broader Prussian-led industrialization that saw Germany's steel output surpass Britain's by 1890.[37][38] Militarily, the province continued to supply recruits to the Prussian army, which formed the backbone of the imperial forces. During the period, conscription drew from the province's population, which grew from about 2.97 million in 1871 to over 3.8 million by 1910, enabling sustained military readiness. The province's strategic position and resources, including fortresses at Magdeburg, enhanced Prussia's defensive capabilities against potential threats. Socially, rapid urbanization and industrial expansion fostered labor movements, with the Social Democratic Party gaining significant support in provincial elections by the early 20th century, highlighting tensions between traditional agrarian conservatism and modern proletarian politics. These dynamics underscored the province's role in the Empire's internal stability and expansionist policies leading up to World War I.[37]Weimar Republic and Interwar Challenges (1919–1933)

The Province of Saxony, as a Prussian administrative unit within the Weimar Republic, experienced the broader national turmoil of political fragmentation and economic volatility, compounded by its mixed agrarian-industrial character. The province's governance fell under the Free State of Prussia's centralized structure, with local administration handled by an Oberpräsident in Magdeburg and a provincial diet (Provinziallandtag) that elected representatives to the Prussian State Council. Early post-war instability manifested in lingering revolutionary fervor, including workers' councils in industrial centers like Halle and Magdeburg, where arms remained in civilian hands, prompting concerns from Prussian authorities about potential uprisings as late as 1921.[39] Reichstag elections in the province's constituencies (Magdeburg, Merseburg, and parts of Thuringia) reflected deepening polarization. In the January 1919 election, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) led with 34.5% of the vote, followed by the Independent Social Democrats (USPD) at 24.8%, indicating strong left-wing support amid demobilization discontent. By June 1920, the USPD surged to 32.6% as economic woes intensified, while conservatives like the German National People's Party (DNVP) gained to 16.8%. The 1924 elections, amid hyperinflation's aftermath, saw DNVP peak at 26.6% in December, with SPD at 27.1% and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) at 13.9%; the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) garnered just 7.1% in May. Stabilization in the late 1920s briefly bolstered SPD to 32.4% in 1928, but the Great Depression catalyzed extremism: NSDAP votes exploded to 19.6% in 1930 and 42.7% in July 1932, surpassing SPD's declining 24.0%, while KPD reached 17.8%. This shift underscored rural and small-town discontent with Weimar's perceived failures, eroding moderate parties like the German People's Party (DVP).[40] Economically, the province's strengths in agriculture (notably around Magdeburg) and industry (chemicals and potash in the Halle-Merseburg Leina Canal area) buffered it somewhat initially but exposed vulnerabilities to national crises. Hyperinflation from 1921–1923 devastated savings and fueled strikes in urban areas, with prices doubling daily by late 1923, though industrial output partially recovered post-Rentemark introduction in November 1923. The province ranked among Prussia's wealthier regions, with advanced farming and manufacturing, yet the 1929 Wall Street Crash triggered mass unemployment, hitting export-dependent sectors like machinery and fertilizers; national figures showed industrial employment dropping 30% between 1925 and 1933, with similar strains in Saxony's factories. Political violence escalated as a result, with street clashes between paramilitaries—SA, Red Front Fighters' League, and others—fostering a culture of civil war fears, as analyzed in case studies of the province's diverse social fabric.[4][41][42] These interwar pressures culminated in radicalization, with the NSDAP's appeal rooted in promises of economic revival and order, drawing from Protestant conservative voters disillusioned by coalition gridlock and reparations burdens under the Treaty of Versailles. The province's experience mirrored Weimar's systemic instabilities—proportional representation amplifying fragmentation—yet its relative prosperity delayed but did not avert the collapse of democratic support by 1932.[40]Nazi Governance and World War II (1933–1945)

The Nazi regime asserted control over the Province of Saxony through the Gleichschaltung process following the Enabling Act of March 23, 1933, subordinating provincial institutions to central party directives and replacing non-compliant officials with NSDAP loyalists. Local Nazi branches, bolstered by widespread support in the province's agrarian and Protestant communities—evidenced by 91.7 percent approval for Nazi policies in the March 1936 Reichstag plebiscite—facilitated the dissolution of trade unions, Social Democratic, and Communist organizations by mid-1933.[43] The provincial Oberpräsident position, overseeing the Regierungsbezirke of Magdeburg, Halle-Merseburg, and Erfurt, became a conduit for implementing racial laws, eugenics programs, and economic regimentation aligned with the Four-Year Plan from 1936 onward. Administrative authority increasingly devolved to the overlapping Nazi Gau structure, with the bulk of the province incorporated into Gau Magdeburg-Anhalt—encompassing northern districts around Magdeburg and adjacent Anhalt territories—where the Gauleiter coordinated party oversight, superseding traditional Prussian provincial bureaucracy in practice.[44] Southern areas near Halle fell under Gau Halle-Merseburg after its formation in 1944, reflecting late-war reorganizations that fragmented the province into separate entities: the Provinces of Magdeburg and Halle-Merseburg, with Erfurt integrated into Thuringia. Nazi governance emphasized autarkic policies, leveraging the province's potash mines, sugar refineries, and chemical facilities for rearmament, while enforcing conscription and ideological indoctrination through institutions like the Hitler Youth and Labor Front. The Jewish community faced escalating persecution from 1933, including boycotts, asset confiscations, and ghettoization precursors; in Magdeburg alone, systematic exclusion from public life culminated in deportations to eastern camps, paralleling broader Gau-level operations.[45] Smaller locales like Ammendorf saw transports of remaining Jews to the Łódź ghetto beginning October 19, 1941, amid coordinated Aktionen that reduced the provincial Jewish population to near extinction by 1943. Political dissidents and Jehovah's Witnesses endured internment in nearby facilities, such as those feeding into Buchenwald subcamps. World War II transformed the province into a linchpin of synthetic fuel production, with the Leuna works near Merseburg—Germany's second-largest chemical complex—producing aviation gasoline and explosives critical to Luftwaffe operations. This drew relentless Allied assaults: the U.S. Eighth Air Force mounted 18 missions against Leuna from May 1944, inflicting cumulative damage equivalent to 80 percent capacity loss despite fierce anti-aircraft defenses that downed over 200 bombers.[46] Urban and transport hubs suffered accordingly; RAF Bomber Command's area raid on Magdeburg on the night of January 16–17, 1945, obliterated 44 percent of the city's built-up area, killing thousands and disrupting Elbe River logistics.[47] Forced labor from occupied territories sustained output amid shortages, but by early 1945, partisan sabotage and desertions eroded control. As Soviet armies penetrated in April 1945, Gau leadership collapsed amid street fighting in Magdeburg and Halle, with retreating Wehrmacht units exacting reprisals against civilians suspected of collaboration. The province's Nazi apparatus disintegrated by May, yielding to Allied occupation and paving the way for postwar partition.[43]Economy

Agricultural Sector and Rural Economy

The Province of Saxony possessed some of the most fertile soils in Prussia, particularly in the Magdeburger Börde and the valleys of the Saale and Unstrut rivers, rendering it the leading agricultural province in terms of productivity. Arable land comprised 61% of the province's approximately 9,750 square miles, supplemented by 13% meadows and pastures and 20.5% forests, which supported intensive crop cultivation and livestock rearing.[16] Wheat and rye were the dominant grains, yielding surpluses for export, while sugar beets emerged as a key cash crop, with production reaching about 400,000 tons in the 1883–1884 campaign, concentrated north of the Harz Mountains and along the Saale. The province outpaced other Prussian regions in wheat and beetroot sugar output, alongside secondary crops such as flax, hops, oil seeds, and fruits; wine grapes were grown near Naumburg but produced lower-quality vintages. These yields benefited from proximity to urban markets like Magdeburg and Halle, fostering technical innovations in crop rotation and seeds during the late 19th century.[16][48] Livestock numbers underscored the sector's vitality, with 1883 statistics recording 182,485 horses, 624,973 head of cattle (concentrated in river valleys), 1,390,915 sheep, 719,627 pigs, and 261,225 goats—the highest goat population in Prussia. Market gardening flourished around Erfurt, enhancing rural diversification.[16] The rural economy centered on large-scale operations dominated by Junker nobility estates east of the Elbe, where holdings exceeding 200 hectares controlled roughly 65% of farmland by the mid-19th century, emphasizing commercial grain and sugar production with wage labor. This structure drove efficiency and output but reinforced conservative social patterns, resisting fragmentation until post-1918 pressures.[16][49]Industrial Development and Urban Centers

The Province of Saxony experienced significant industrial growth from the mid-19th century onward, fueled by access to the Elbe River for transportation, expanding rail networks, and Prussian investments in infrastructure following the Stein-Hardenberg reforms. Mechanical engineering emerged as a cornerstone, particularly in the production of heavy machinery, boilers, and later armor plating, with over 38 technical innovations patented in the region between 1823 and 1899. By 1886, Magdeburg alone hosted 43 machine factories and 8 specialized boiler manufacturers, establishing it as a cradle of German machine building.[50][51] Mining and extractive industries also thrived, notably copper and silver production in the Mansfeld district, where operations dating to the 12th century intensified with industrial-scale techniques, yielding one of Europe's largest copper-slate deposits and employing mechanized extraction methods by the late 19th century. Chemical processing developed around local resources like salt in Halle and potash precursors, laying groundwork for later expansions, while sugar refining and food industries supported rural-urban linkages. These sectors contributed to the province's reputation as one of Prussia's wealthiest, with industry complementing advanced agriculture.[52][53] Urban centers anchored this development, with Magdeburg serving as the provincial capital and primary industrial hub, its machine firms like Grusonwerk (founded 1855) exporting globally and driving population influx through factory labor.[54][55] Halle (Saale), the second-largest city, integrated chemical and mechanical industries with its university, fostering innovations in processing local minerals and supporting a diverse economy including food production. Smaller centers like Merseburg and Hettstedt specialized in extractives, with Mansfeld's mining sustaining regional employment into the 20th century despite environmental costs from slag and emissions.[51]Society and Culture

Education, Science, and Intellectual Contributions

The Province of Saxony's education system adhered to the centralized Prussian model, which mandated compulsory elementary schooling from age 5 or 6 for eight years starting in the late 18th century, emphasizing rote learning, discipline, and moral instruction to produce obedient subjects and soldiers.[56] This framework extended to the province's rural and urban areas, with Volksschulen (primary schools) in towns like Magdeburg and Halle achieving literacy rates exceeding 90% by the mid-19th century, surpassing many European counterparts due to state funding and teacher seminaries established under reforms by Johann Julius Hecker and August Hermann Francke's legacy institutions.[57] Secondary education via Gymnasien focused on classical languages and sciences, preparing elites for civil service or academia, while Realschulen catered to technical vocations amid industrialization. Higher education anchored in the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, merged in 1817 from the 1694-founded University of Halle and the 1502 University of Wittenberg, which by the mid-19th century saw expansion in natural sciences and medicine under Prussian investment post-Humboldtian reforms.[58] The institution hosted faculties advancing physiology, chemistry, and physics; for instance, professors contributed to early electromagnetic research, with Johann Christoph Schweigger inventing the galvanometer in 1820 at Halle to quantify electric current, enabling precise measurements foundational to later electrodynamics.[59] Agricultural sciences also flourished, with institutes in Halle developing experimental methods for crop improvement amid the province's fertile Elbe valley, supporting Prussia's economic modernization.[60] Intellectual output included the Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina in Halle, relocated there in 1878, which coordinated empirical research across disciplines and elected members like physicists and chemists whose work influenced imperial Germany's scientific prestige, though constrained by state oversight.[61] In the early 20th century, amid Weimar-era dynamism, Halle scholars advanced oncology and botany—e.g., Arnold Graffi's pioneering tumor induction experiments in the 1930s–1940s—but Nazi policies from 1933 imposed ideological purges, prioritizing "Aryan physics" and applied military research over pure inquiry, reducing the province's output until 1945.[62] These contributions underscored Saxony's role in Prussia's shift from theological humanism to empirical technoscience, though often subordinated to national imperatives rather than unfettered discovery.Religious Dynamics and Social Institutions

The Province of Saxony exhibited a strongly Protestant religious landscape throughout its existence, shaped by the Lutheran Reformation and subsequent Prussian state policies. In the 1871 census, Protestants constituted approximately 93.5% of the population (1,966,696 individuals), with Roman Catholics at 6.0% (126,735), Jews at 0.3% (5,917), and negligible others.[25] This composition reflected the region's integration into the Evangelical Church of the Prussian Union, established in 1817 by King Frederick William III to merge Lutheran and Reformed traditions under a unified liturgical agenda, including the introduction of an ecumenical hymnbook and prayer book.[8] While the Union fostered administrative cohesion across Prussian territories like Saxony, it provoked resistance from confessional Lutherans who viewed the reforms as diluting doctrinal purity, leading to schisms such as the Old Lutheran movement and emigrations in the 1830s.[8] Catholic communities, concentrated in areas like Erfurt acquired from electoral Saxony, maintained distinct diocesan structures under the Paderborn diocese until 1905, comprising about 8% of residents by the early 20th century.[8] Jewish populations, though small, were urban and integrated into municipal life, with synagogues serving as centers for communal welfare amid rising secular pressures. Religious dynamics evolved amid industrialization and urbanization, with church attendance declining from the late 19th century due to socialist influences in working-class centers like Halle and Magdeburg, yet Protestant institutions retained influence through state-supported consistories overseeing parish governance.[63] Social institutions in the province were deeply intertwined with religious bodies, particularly the Evangelical Church, which administered elementary education via confessional schools until secular reforms in the 1920s and provided diaconal services for the poor, orphans, and elderly through parish-based welfare systems.[26] These efforts complemented state initiatives, with church-run hospitals and savings associations in Protestant strongholds promoting moral and economic stability amid rural depopulation and urban poverty. During the Weimar era, church synods addressed social fragmentation, but Nazi governance from 1933 introduced tensions, as the Church Province of Saxony grappled with pro-regime German Christian factions seeking alignment with National Socialism versus Confessing Church adherents prioritizing theological independence from state control.[63] By World War II, these institutions faced resource strains, yet retained roles in community cohesion until the province's dissolution in 1945.Cultural Heritage and Local Traditions

The Province of Saxony preserved a distinct Protestant cultural heritage, rooted in the Lutheran Reformation, with key sites like the former Augustinian monastery in Eisleben—where Martin Luther was born in 1483—and influences extending to nearby Wittenberg, fostering traditions of hymn-singing and ecclesiastical music that persisted through the Prussian era. Architectural landmarks, such as the Magdeburg Cathedral, exemplify Gothic heritage, with construction commencing in 1209 under Archbishop Albert I, making it among Germany's earliest fully Gothic structures dedicated to Saints Maurice and Catherine.[64] In Halle, the Marktkirche Unser Lieben Frauen, begun in the 14th century, served as a center for Reformation preaching and community gatherings, underscoring the province's role in religious cultural continuity.[65] Musical traditions thrived amid this milieu, with the province as the birthplace of Baroque composers including Georg Philipp Telemann, born in Magdeburg in 1681, who drew on local organ and choral practices, and George Frideric Handel, born in Halle in 1685, whose early works reflected the region's court and church music heritage before his relocation to England.[64] [66] These contributions embedded a legacy of sacred music performances, evident in annual festivals and university ensembles at the University of Halle, founded in 1694. Local traditions emphasized agrarian and folk customs, particularly in rural districts. Walpurgis Night, observed on April 30 in Harz locales like Thale and Schierke within the province's northern reaches, traces to pre-Christian pagan rites conflated with Christian saints, featuring bonfires and processions evoking witches' sabbaths on the Brocken peak, a motif dramatized in Goethe's Faust (published 1808 and 1832).[67] The Candlemas festival in Spergau, near Halle and first recorded in 1688, involved youth-led gift collections for the needy followed by a communal purification bonfire on the first Sunday after February 2, blending charitable and ritual elements.[68] In Ströbeck near Halberstadt, chess cultivation emerged as a village custom by the late 16th century, with residents breeding specialized strains of the game and hosting tournaments, sustaining a guild-like tradition into the 20th century.[69] The Brunnenfest in Bad Dürrenberg, dating over 250 years to the mid-18th century, commemorated the 1725 discovery of therapeutic saltwater springs through parades, folk plays like the Borlachspiel, and markets, highlighting the province's mineral resource-based communal rites.[70] These practices, often tied to seasonal cycles and local resources, endured under Prussian administration, fostering regional identity amid agricultural economies.Dissolution and Legacy

Post-World War II Dismantling

Following Germany's unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, the territory of the Province of Saxony came under Soviet occupation as part of the Soviet Zone of Occupation (SBZ). The Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) initiated administrative reforms aimed at dismantling Prussian provincial structures to promote decentralization and eliminate perceived militaristic legacies of the Prussian state. This process involved the dissolution of the Province of Saxony as a distinct Prussian entity, with its core areas reconfigured into a new administrative unit.[71] In July 1945, SMAD reorganized the SBZ by converting former Prussian provinces and smaller states into Länder (states), bypassing the centralized Prussian framework. The bulk of the Province of Saxony—excluding its Erfurt administrative district (Regierungsbezirk Erfurt), which was transferred to the state of Thuringia—was merged with the Free State of Anhalt and minor adjacent territories to form the Province of Saxony-Anhalt (initially termed the "New Province of Saxony"). This new province encompassed approximately 24,000 square kilometers and a population of around 4.5 million by late 1945, reflecting a deliberate consolidation to streamline Soviet oversight while fragmenting historical Prussian cohesion.[71] The Erfurt district's detachment, covering about 7,500 square kilometers including cities like Erfurt and Mühlhausen, severed a significant eastern portion of the former province, aligning it with Thuringia's boundaries for administrative efficiency under Soviet control. Border adjustments also occurred, such as minor territorial exchanges with neighboring states like Brandenburg, to rationalize post-war demographics and resource distribution amid expulsions of German populations from eastern territories. These changes effectively ended the Province of Saxony's independent existence by autumn 1945, transitioning its institutions—such as provincial governments in Magdeburg and Halle—to the new Saxony-Anhalt framework under local communist-influenced administrations.[71] On February 25, 1947, Allied Control Council Law No. 46 formally abolished the state of Prussia across all occupation zones, retroactively confirming the provincial dismantling and prohibiting any Prussian revival. Within Saxony-Anhalt, a state constitution adopted on January 16, 1947, elevated the province to full Land status, further entrenching the reconfiguration with a unicameral legislature and executive led by figures like Erhard Hübener of the Liberal Democratic Party. This marked the complete erasure of the Province of Saxony's pre-war administrative identity, though its districts influenced the later 1952 GDR district reforms that subdivided Saxony-Anhalt into Bezirk Magdeburg and Bezirk Halle.[71]Influence on Modern German Federal States

The dissolution of the Province of Saxony in 1945 directly informed the territorial configuration of modern German federal states in central Germany. The Soviet Military Administration reorganized the province by detaching its Erfurt Regierungsbezirk and incorporating it into the state of Thuringia, while merging the remaining Regierungsbezirke of Magdeburg and Merseburg with the adjacent Free State of Anhalt to establish the state of Saxony-Anhalt on July 23, 1945.[72][73] This division preserved the province's core northern and central territories—spanning approximately 25,000 square kilometers excluding Erfurt—within Saxony-Anhalt, which adopted Magdeburg as its provisional capital before formalizing the structure.[8] These post-war boundaries exerted lasting influence despite subsequent administrative changes. In 1952, under the German Democratic Republic, Saxony-Anhalt was subdivided into the districts (Bezirke) of Magdeburg, Halle, and parts of others, directly echoing the province's pre-existing Regierungsbezirke and facilitating continuity in local governance and economic planning.[74] Following German reunification on October 3, 1990, Saxony-Anhalt was reconstituted as a federal state with frontiers substantially aligned to the 1945 delineation, encompassing 20,445 square kilometers and a population of about 2.2 million as of 2023, thereby perpetuating the Province of Saxony's spatial legacy in administrative districts like Jerichower Land and Salzlandkreis.[73] In Thuringia, the integration of the Erfurt area—historically administered from the province since 1815—bolstered the state's central region, including the city of Erfurt with its 214,000 residents, and contributed to Thuringia's total area of 16,171 square kilometers.[72] The province's influence extends beyond cartography to socioeconomic patterns in these Länder. Agricultural productivity in northern Saxony-Anhalt, rooted in the province's fertile Magdeburg Börde plains that yielded high grain outputs pre-1945, remains a cornerstone of the state's economy, with over 50% of its land arable as of recent agricultural censuses.[8] Similarly, the chemical and mining industries clustered around Halle-Merseburg, which employed tens of thousands in the early 20th century, evolved into modern sectors like biotechnology in Saxony-Anhalt and manufacturing in Thuringia's Erfurt vicinity, underscoring causal continuities in regional specialization despite ideological shifts post-1945.[75] Cultural institutions, such as the University of Halle founded in 1694 under provincial oversight, continue to anchor intellectual life, reinforcing historical ties to the Prussian administrative framework.[8]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Final_Act_of_the_Congress_of_Vienna/Act_IV