Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pyrethrin

View on Wikipedia

The pyrethrins are a class of organic compounds normally derived from Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium that have potent insecticidal activity by targeting the nervous systems of insects. Pyrethrin naturally occurs in chrysanthemum flowers and is often considered an organic insecticide when it is not combined with piperonyl butoxide or other synthetic adjuvants.[1] Their insecticidal and insect-repellent properties have been known and used for thousands of years.

Pyrethrins are gradually replacing organophosphates and organochlorides as the pesticides of choice as the latter compounds have been shown to have significant and persistent toxic effects to humans. They first appeared on markets in the 1900s and have been continually used since then in products such as bug bombs, building insect sprays, and even to spray animals so that they do not get infectious diseases.[2]

Chemistry

[edit]| Group | Pyrethrin I | Pyrethrin II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical compound | Pyrethrin I[3][4] | Cinerin I[5][4] | Jasmolin I[6] | Pyrethrin II[7][4] | Cinerin II[8][4] | Jasmolin II[9] |

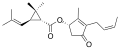

| Chemical structure |

|

|||||

| Chemical formula | C21H28O3 | C20H28O3 | C21H30O3 | C22H28O5 | C21H28O5 | C22H30O5 |

| Molecular mass (g/mol) | 328.4 | 316.4 | 330.5 | 372.5 | 360.4 | 374.5 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 170 | 137 | ? | 200 | 183 | ? |

| Vapor pressure at 25 °C (mmHg) | 2.03×10−5 | 1.13×10−6 | ? | 3.98×10−7 | 4.59×10−7 | ? |

| Solubility in water (mg/L) | 0.2 | 0.085 | ? | 9.0 | 0.03 | ? |

History

[edit]The pyrethrins occur in the seed cases of the perennial plant pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium), which has long been grown commercially to supply the insecticide. In the 1880s, pyrethrum cultivation began in Japan when Ueyama grew the flowers in Wakayama and promoted their use across the country, primarily for lice control. Inspired by this, his wife Yuki conceptualized the mosquito coil, which became an effective and globally used tool against mosquitoes. Scientific interest followed, with biologist Fujitani publishing the first study on pyrethrum's insecticidal properties in 1909, sparking international chemical research. In 1923, Yamamoto identified that the active compounds in pyrethrum contained a cyclopropane ring, building on interest from Umetaro Suzuki. Later, Staudinger and Ruzicka analyzed the compounds in depth, and in 1944, LaForge and Barthel finally confirmed the full structures of pyrethrins I and II, along with cinerins I and II.[10]

Biosynthesis

[edit]

Well after their use as insecticides began, their chemical structures were determined by Hermann Staudinger and Lavoslav Ružička in 1924.[11] Pyrethrin I (CnH28O3) and pyrethrin II (CnH28O5) are structurally related esters with a cyclopropane core. Pyrethrin I is a derivative of (+)-trans-chrysanthemic acid.[12][13] Pyrethrin II is closely related, but one methyl group is oxidized to a carboxymethyl group, the resulting core being called pyrethric acid. Knowledge of their structures opened the way for the production of synthetic analogues, which are called pyrethroids. Pyrethrins are classified as terpenoids. The key step in the biosynthesis of the naturally occurring pyrethrins involves two molecules of dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, which join to form a cyclopropane ring by the action of the enzyme chrysanthemyl diphosphate synthase.[14]

Production

[edit]

Commercial pyrethrin production mainly takes place in mountainous equatorial zones. The commercial cultivation of the Dalmatian chrysanthemum (C. cinerariifolium) takes place at an altitude of 1600 to 3000 meters[15] above sea level.[16] This is done because pyrethrin concentration has been shown to increase as elevation increases to this level. Growing these plants does not require much water because semiarid conditions and a cool winter deliver optimal pyrethrin production. The Persian chrysanthemum C. coccineum also produces pyrethrins but at a much lower level. Both may be planted in low-altitude zones in dry soil, but the pyrethrin level is lower.[15]

Pyrethrum extracted of the Persian chrysanthemum (painted daisy) was already imported to central Europe from Georgia in the middle of the 19th century. Most of the world's supply of pyrethrin and C. cinerariaefolium today comes from Kenya, which produces the most potent flowers. Other countries include Croatia (in Dalmatia) and Japan. The flower was first introduced into Kenya and the highlands of Eastern Africa during the late 1920s. Since the 2000s, Kenya has produced about 70% of the world's supply of pyrethrum.[17] A substantial amount of the flowers are cultivated by small-scale farmers who depend on it as a source of income. It is a major source of export income for Kenya and source of over 3,500 additional jobs. About 23,000 tons were harvested in 1975. The active ingredients are extracted with organic solvents to give a concentrate containing the six types of pyrethrins: pyrethrin I, pyrethrin II, cinerin I, cinerin II, jasmolin I, and jasmolin II.[18]

Processing the flowers to cultivate the pyrethrin is often a lengthy process, and one that varies from area to area. For instance, in Japan, the flowers are hung upside down to dry which increases pyrethrin concentration slightly.[15] To process pyrethrin, the flowers must be crushed. The degree to which the flower is crushed has an effect on both the longevity of the pyrethrin usage and the quality. The finer powder produced is better suited for use as an insecticide than the more coarsely crushed flowers. However, the more coarsely crushed flowers have a longer shelf life and deteriorate less.[15]

Use as an insecticide

[edit]Pyrethrin is most commonly used as an insecticide and has been used for this purpose since the 1900s.[18] In the 1800s, it was known as "Persian powder", "Persian pellitory", and "zacherlin". Pyrethrins delay the closure of voltage-gated sodium channels in the nerve cells of insects, resulting in repeated and extended nerve firings. This hyperexcitation causes the death of the insect due to loss of motor coordination and paralysis.[19] Resistance to pyrethrin has been bypassed by pairing the insecticide with synthetic synergists such as piperonyl butoxide. Together, these two compounds prevent detoxification in the insect, ensuring insect death.[20] Synergists make pyrethrin more effective, allowing lower doses to be effective. Pyrethrins are effective insecticides because they selectively target insects rather than mammals due to higher insect nerve sensitivity, smaller insect body size, lower mammalian skin absorption, and more efficient mammalian hepatic metabolism.[21] Also, mammals are able to process pyrethrin quickly and have higher body temperatures which prevent pyrethrin from working effectively [22]

Although pyrethrin is a potent insecticide, it also functions as an insect repellent at lower concentrations. Observations in food establishments demonstrate that flies are not immediately killed, but are found more often on windowsills or near doorways. This suggests, due to the low dosage applied, that insects are driven to leave the area before dying.[23] Because of their insecticide and insect repellent effect, pyrethrins have been very successful in reducing insect pest populations that affect humans, crops, livestock, and pets, such as ants, spiders, and lice, as well as potentially disease-carrying mosquitoes, fleas, and ticks.

As pyrethrins and pyrethroids are increasingly being used as insecticides, the number of illnesses and injuries associated with exposure to these chemicals is also increasing.[24] However, few cases leading to serious health effects or mortality in humans have occurred, which is why pyrethroids are labeled "low-toxicity" chemicals and are ubiquitous in home-care products.[21] Pyrethrins are widely regarded as better for the environment, and can be harmless if used only in the field with localized sprays, as UV exposure breaks them down into harmless compounds. Additionally, they have little lasting effect on plants, degrading naturally or being degraded by the cooking process.[25]

Specific pest species that have been successfully controlled by pyrethrum include: potato, beet, grape, and six-spotted leafhopper, cabbage looper, celery leaf tier, Say's stink bug, twelve-spotted cucumber beetle, lygus bugs on peaches, grape and flower thrips, and cranberry fruitworm.[26]

Toxicity

[edit]Pyrethrins are among the safest insecticides on the market due to their rapid degradation in the environment.

Similarities between the chemistry of pyrethrins and synthetic pyrethroids include a similar mode of action and almost identical toxicity to insects (i.e., both pyrethrins and pyrethroids induce a toxic effect within the insect by acting on sodium channels).[27]

Some differences in the chemistry between pyrethrins and synthetic pyrethroids have the result that synthetic pyrethroids have relatively longer environmental persistence than do pyrethrins. Pyrethrins have shorter environmental persistence than synthetic pyrethroids because their chemical structure is more susceptible to the presence of UV light and changes in pH.[citation needed]

The use of pyrethrin in products such as natural insecticides and pet shampoo, for its ability to kill fleas, increases the likelihood of toxicity in mammals that are exposed. Medical cases have emerged showing fatalities from the use of pyrethrin, prompting many organic farmers to cease use. One fatal case of an 11-year-old girl with a known asthmatic condition and who used shampoo containing only a small amount (0.2% pyrethrin) to wash her dog was documented.[28]

Chronic pyrethrin toxicity in humans

[edit]Chronic toxicity in humans occurs most quickly through respiration into the lungs, or more slowly through absorption through the skin.[29] Allergic reactions may occur after exposure, leading to itching and irritated skin as well as burning sensations.[30] These types of reactions are rare because the allergenic component of pyrethrin in semi-synthetic pyrethroids has been removed.[31] The metabolite compounds of pyrethrin are less toxic to mammals than their originators, and compounds are either broken down in the liver or gastrointestinal tract, or excreted through feces; no evidence of storage in tissues has been found [citation needed].

Pyrethrum toxicity

[edit]Exposure to pyrethrum, the crude form of pyrethrin,[31] causes harmful health effects for mammals. Pyrethrum also has an allergenic effect that commercial pyrethroids don't have.[31] In mammals, toxic exposure to pyrethrum can lead to tongue and lip numbness, drooling, lethargy, muscle tremors, respiratory failure, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, paralysis, and death.[29] Exposure to pyrethrum in high levels in humans may cause symptoms such as asthmatic breathing, sneezing, nasal stuffiness, headache, nausea, loss of coordination, tremors, convulsions, facial flushing, and swelling.[32][unreliable source?] A possibility of damage to the immune system exists that leads to a worsening of allergies following toxicity.[29] Infants are unable to resourcefully break down pyrethrum due to the ease of skin penetration, causing similar symptoms as adults, but with an increased risk of death.[33]

Feline Toxicity

[edit]A cat's liver is not able to metabolize pyrethrin making it toxic to cats. Exposure often results from a flea and tick treatment for dogs being used on a cat.[34]

Environmental effects

[edit]Aquatic habitats

[edit]In aquatic settings, toxicity of pyrethrin fluctuates, increasing with rising temperatures, water, and acidity. Run-off after application has become a concern for sediment-dwelling aquatic organisms because pyrethroids can accumulate in these areas.[35] Aquatic life is extremely susceptible to pyrethrin toxicity, and has been documented in species such as the lake trout. Although pyrethrins are quickly metabolized by birds and most mammals, fish and aquatic invertebrates lack the ability to metabolize these compounds, leading to a toxic accumulation of byproducts.[29] To combat the accumulation of pyrethroids in bodies of water, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has introduced two labeling initiatives. The Environmental Hazard and General Labeling for Pyrethroid and Synergized Pyrethrins Non-Agricultural Outdoor Products was revised in 2013 to reduce runoff into bodies of water after use in residential, commercial, institutional, and industrial areas.[36] The Pyrethroid Spray Drift Initiative updated language for labeling all pyrethroid products to be used on agricultural crops.[36] Because of its high toxicity to fish and aquatic invertebrates even at low doses, the EPA recommends alternatives such as pesticide-free methods or alternative chemicals that are less harmful to the surrounding aquatic environment.[37]

Terrestrial Habitats

[edit]Pyrethrin is mainly used on land and can also have impacts in the places that it is used. For instance pyrethrin has the ability to be persistent in the fields that it is sprayed on. This persistence in crops can lead to negative effects for meat production.[38]

Bees

[edit]Pyrethrins are applied broadly as nonspecific insecticides. Bees have been shown to be particularly sensitive to pyrethrin, with fatal doses as small as 0.02 micrograms.[1] Due to this sensitivity and pollinator decline, pyrethrins are recommended to be applied at night to avoid typical pollinating hours, and in liquid rather than dust form.[39]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mader, Eric, and Nancy Lee Adamson. "Organic-Approved Pesticides."Organic-Approved Pesticides (n.d.): n. pag. The Xerxes Society. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, Oct. 2012. Web. 10 Mar. 2015. <http://www.xerces.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/xerces-organic-approved-pesticides-factsheet.pdf Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ "Pyrethrins General Fact Sheet". npic.orst.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ^ CID 5281045 from PubChem

- ^ a b c d "Pyrethrins or Pyrethrum". In: Pohanish, Richard P. (2015). "P". Sittig's Handbook of Pesticides and Agricultural Chemicals. pp. 629–724. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4557-3148-0.00016-9. ISBN 978-1-4557-3148-0.

- ^ PubChem. "Cinerin I". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ CID 12304687 from PubChem

- ^ PubChem. "Pyrethrin II". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ CID 5281548 from PubChem

- ^ CID 12304690 from PubChem

- ^ MATSUO N (2019). "Discovery and development of pyrethroid insecticides". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences. 95 (7): 378–400. Bibcode:2019PJAB...95..378M. doi:10.2183/pjab.95.027. PMC 6766454. PMID 31406060.

- ^ Staudinger, H.; Ruzicka, L. (1924). "Insektentötende Stoffe I. Über Isolierung und Konstitution des wirksamen Teiles des dalmatinischen Insektenpulvers" [Insecticidal substances I. About the isolation and structure of the active part of the Dalmatian insect powder]. Helvetica Chimica Acta (in German). 7 (1): 177–201. Bibcode:1924HChAc...7..177S. doi:10.1002/hlca.19240070124.

- ^ Merck Index (11th ed.). p. 7978.[full citation needed]

- ^ Townsend, Michael. McGraw-Hill Ryerson Chemistry 12. p. 99.[full citation needed]

- ^ Rivera, S. B.; Swedlund, B. D.; King, G. J.; Bell, R. N.; Hussey, C. E.; Shattuck-Eidens, D. M.; Wrobel, W. M.; Peiser, G. D.; Poulter, C. D. (2001). "Chrysanthemyl diphosphate synthase: Isolation of the gene and characterization of the recombinant non-head-to-tail monoterpene synthase from Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (8): 4373–8. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.4373R. doi:10.1073/pnas.071543598. JSTOR 3055437. PMC 31842. PMID 11287653.

- ^ a b c d "HOME PRODUCTION OF PYRETHRUM." Home Production of Pyrethrum. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Apr. 2015.

- ^ Anonym. 1987 (March). Pepping up pesticides naturally. Organic Gardening, 34(3):8.

- ^ Wainaina, Job M. G. (1995). "Pyrethrum Flowers -- Production in Africa". In Casida, John E.; Quistad, Gary B. (eds.). Pyrethrum Flowers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508210-9.

- ^ a b Metcalf, Robert L. (2000). "Insect Control". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_263. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ "Pyrethrins General Fact Sheet." National Pesticide Information Center (n.d.): n. pag. Nov. 2014. Web. 26 Apr. 2015. <http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/pyrethrins.pdf>

- ^ "Pyrethrin." Asktheexterminator.com. Ask the Exterminator, 2011. Web. 2 Apr. 2015. <http://www.asktheexterminator.com/Pesticide/Pyrethrin.shtml Archived 2011-09-04 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ a b Bradberry, S. M.; Cage, S. A.; Proudfoot, A. T.; Vale, J. A. (2005). "Poisoning due to pyrethroids". Toxicological Reviews. 24 (2): 93–106. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524020-00003. PMID 16180929.

- ^ Ensley, Steve M. (2018). "Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids". Veterinary Toxicology. pp. 515–520. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-811410-0.00039-8. ISBN 978-0-12-811410-0.

- ^ Todd, G Daniel, David Wohlers, and Mario Citra. "Toxicological Profile for Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids." ATSDR. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Sept. 2001. Web. 26 Apr. 2015. <http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp155.pdf>

- ^ Power, Laura E.; Sudakin, Daniel L. (2007). "Pyrethrin and pyrethroid exposures in the United States: A longitudinal analysis of incidents reported to poison centers". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 3 (3): 94–9. doi:10.1007/BF03160917. PMC 3550062. PMID 18072143.

- ^ Vettorazzi, G. (1979). International Regulatory Aspects for Pesticide Chemicals. CRC Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780849356070.

- ^ Caldwell, Brian, Eric Sideman, Abby Seaman, Anthony Shelton, and Christine Smart. "Resource Guide for Organic Insect and Disease Management." (n.d.): n. pag. Cornell University, 2013. Web. 23 Mar. 2015. <https://web.pppmb.cals.cornell.edu/resourceguide/pdf/resource-guide-for-organic-insect-and-disease-management.pdf>

- ^ Matsuo, Noritada (31 July 2019). "Discovery and development of pyrethroid insecticides". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B. 95 (7): 378–400. Bibcode:2019PJAB...95..378M. doi:10.2183/pjab.95.027. PMC 6766454. PMID 31406060.

- ^ Wagner, S. L. (2000). "Fatal asthma in a child after use of an animal shampoo containing pyrethrin". The Western Journal of Medicine. 173 (2): 86–7. doi:10.1136/ewjm.173.2.86. PMC 1071005. PMID 10924422.

- ^ a b c d "Pyrethrins". Extension Toxicology Network. 1996.

- ^ Aldridge, W. N. (1990). "An Assessment of the Toxicological Properties of Pyrethroids and Their Neurotoxicity". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 21 (2): 89–104. doi:10.3109/10408449009089874. PMID 2083034.

- ^ a b c "Review of the Relationship between Pyrethrins, Pyrethroid Exposure and Asthma and Allergies". US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs. Sep 2009. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009.

- ^ Occupational Health Services, Inc. "Pyrethrum." Material Safety Data Sheet. 1 April 1987. New York: OHS, Inc.

- ^ "Public Health Statement for Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids". Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. Sep 2003.

- ^ "Pyrethrin Toxicity in Cats". MSPCA-Angell. Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ "Pyrethroids and Pyrethrins". EPA. Dec 2013. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009.

- ^ a b "Environmental Hazard and General Labeling for Pyrethroid Non-Agricultural Outdoor Products". EPA. Feb 2013. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009.

- ^ "Pyrethroids and Pyrethrins." EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, Dec. 2013. Web. 26 Apr. 2015. <[1]>

- ^ Farag, Mayada R.; Alagawany, Mahmoud; Bilal, Rana M.; Gewida, Ahmed G. A.; Dhama, Kuldeep; Abdel-Latif, Hany M. R.; Amer, Mahmoud S.; Rivero-Perez, Nallely; Zaragoza-Bastida, Adrian; Binnaser, Yaser S.; Batiha, Gaber El-Saber; Naiel, Mohammed A. E. (2021-06-25). "An Overview on the Potential Hazards of Pyrethroid Insecticides in Fish, with Special Emphasis on Cypermethrin Toxicity". Animals. 11 (7): 1880. doi:10.3390/ani11071880. PMC 8300353. PMID 34201914.

- ^ Hooven, L., R. Sagili, and E. Johansen. "How to Reduce Bee Poisoning from Pesticides." (n.d.): n. pag. Oregon State University, Dec. 2006. Web. 23 Mar. 2015. <http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PDF/PMG/pnw591.pdf>

External links

[edit]- International Center for Pyrethrum research

- Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Pyrethrins and pyrethroids on the EXTOXNET

- Pyrethrin and Permethrin Toxicity in Dogs and Cats

- Wagner, S. L. (2000). "Fatal asthma in a child after use of an animal shampoo containing pyrethrin". The Western Journal of Medicine. 173 (2): 86–7. doi:10.1136/ewjm.173.2.86. PMC 1071005. PMID 10924422.

- Horton, M. K.; Rundle, A.; Camann, D. E.; Boyd Barr, D.; Rauh, V. A.; Whyatt, R. M. (2011). "Impact of Prenatal Exposure to Piperonyl Butoxide and Permethrin on 36-Month Neurodevelopment". Pediatrics. 127 (3): e699–706. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0133. PMC 3065142. PMID 21300677.

- "Common insecticide used in homes associated with delayed mental development of young children". ScienceDaily (Press release). February 10, 2011.