Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

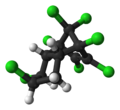

Chlordane

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,7-methanoindane | |||

| Other names

Chlordan; Chlordano; Ortho; Octachloro-4,7-methanohydroindane

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.317 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2996 2762 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H6Cl8 | |||

| Molar mass | 409.76 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White solid | ||

| Odor | Slightly pungent, chlorine-like | ||

| Density | 1.59 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 102–106 °C (216–223 °F; 375–379 K)[1] | ||

| Boiling point | decomposes[1] | ||

| 0.0001% (20°C)[1] | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.565 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

moderately toxic and a suspected human carcinogen | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301, H311, H351, H410 | |||

| P201, P273, P280, P301+P310+P330, P302+P352+P312[2] | |||

| Flash point | 107 °C (225 °F; 380 K) (open cup) | ||

| Explosive limits | 0.7–5% | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

100-300 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) 145-430 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 200-590 mg/kg (rat, oral) 1720 mg/kg (hamster, oral)[3] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 [skin][1] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

Ca TWA 0.5 mg/m3 [skin][1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

100 mg/m3[1] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Chlordane (technical mixture) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Chlordane, or chlordan, is an organochlorine compound that was used as a pesticide. It is a white solid. In the United States, chlordane was used for termite-treatment of approximately 30 million homes until it was banned in 1988.[4] Chlordane was banned 10 years earlier for food crops like corn and citrus, and on lawns and domestic gardens.[5]

Like other chlorinated cyclodiene insecticides, chlordane is classified as an organic pollutant hazardous for human health. It is resistant to degradation in the environment and in humans/animals and readily accumulates in lipids (fats) of humans and animals.[6] Exposure to the compound has been linked to cancers, diabetes, and neurological disorders.

Production, composition and uses

[edit]Technical chlordane development was by chance at Velsicol Chemical Corporation by Julius Hyman in 1948, during a search for possible uses of a by-product of synthetic rubber manufacturing. By chlorinating this by-product, persistent and potent insecticides were easily and cheaply produced. The chlorine atoms, 7 in the case of heptachlor, 8 in chlordane, and 9 in the case of nonachlor, surround and stabilize the cyclodiene ring and thus these compounds are referred to as cyclodienes. Other members of the cyclodiene family of organochlorine insecticides are aldrin and its epoxide, dieldrin, as well as endrin, which is a stereoisomer of dieldrin. Cyclodiene derives its name from hexachlorocyclopentadiene, a precursor in its production.

Hexachlorocyclopentadiene forms a Diels-Alder adduct with cyclopentadiene to give chlordene intermediate [3734-48-3]; chlorination of this adduct gives predominantly two chlordane isomers, α and β, in addition to other products such as trans-nonachlor and heptachlor.[7] The β-isomer is popularly known as gamma and is more bioactive.[5] The mixture that is composed of 147 components is called technical chlordane.[8][9]

-

cis-chlordane (also known as α-chlordane (CAS=5103-71-9))

-

trans-chlordane (also known as γ-chlordane and gamma-chlordane (CAS=5103-74-2))

-

trans-nonachlor

-

(+)-heptachlor

Chlordane appears as a white or off-white crystals when synthesized, but it was more commonly sold in various formulations as oil solutions, emulsions, sprays, dusts, and powders. These products were sold in the United States from 1948 to 1988.

Because of concern for harm to human health and to the environment, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned all uses of chlordane in 1983, except termite control in wooden structures (e.g. houses). After many reports of chlordane in the indoor air of treated homes, EPA banned the remaining use of chlordane in 1988.[10] The EPA recommends that children should not drink water with more than 60 parts of chlordane per billion parts of drinking water (60 ppb) for longer than 1 day. EPA has set a limit in drinking water of 2 ppb.[citation needed]

Chlordane is very persistent in the environment because it does not break down easily. Tests of the air in the residence of U.S. government housing, 32 years after chlordane treatment, showed levels of chlordane and heptachlor 10-15 times the Minimal Risk Levels (20 nanograms/cubic meter of air) published by the Centers for Disease Control.[citation needed] It has an environmental half-life of 10 to 20 years.[11]

Origin, pathways of exposure, and processes of excretion

[edit]

In the years 1948–1988 chlordane was a common pesticide for corn and citrus crops, as well as a method of home termite control.[6] Pathways of exposure to chlordane include ingestion of crops grown in chlordane-contaminated soil, inhalation of air in chlordane-treated homes and from landfills, and ingestion of high-fat foods such as meat, fish, and dairy, as chlordane builds up in fatty tissue.[12] The United States Environmental Protection Agency reported that over 30 million homes were treated with technical chlordane or technical chlordane with heptachlor. Depending on the site of home treatment, the indoor air levels of chlordane can still exceed the Minimal Risks Levels (MRLs) for both cancer and chronic disease by orders of magnitude.[13] Chlordane is excreted slowly through feces, urine elimination, and through breast milk in nursing mothers. It is able to cross the placenta and become absorbed by developing fetuses in pregnant women.[14] A breakdown product of chlordane, the metabolite oxychlordane, accumulates in blood and adipose tissue with age.[15]

Environmental impact

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2017) |

Being hydrophobic, chlordane adheres to soil particles and enters groundwater only slowly, owing to its low solubility (0.009 ppm). It requires many years to degrade.[16] Chlordane bioaccumulates in animals.[17] It is highly toxic to fish, with an LD50 of 0.022–0.095 mg/kg (oral).

Oxychlordane (C10H4Cl8O), the primary metabolite of chlordane, and heptachlor epoxide, the primary metabolite of heptachlor, along with the two other main components of the chlordane mixture, cis-nonachlor and trans-nonachlor, are the main bioaccumulating constituents.[8] trans-Nonachlor is more toxic than technical chlordane and cis-nonachlor is less toxic.[8]

Chlordane and heptachlor are known as persistent organic pollutants (POP), classified among the "dirty dozen" and banned by the 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.[18]

Health effects

[edit]Exposure to chlordane/heptachlor and/or its metabolites (oxychlordane, heptachlor epoxide) are risk factors for type-2 diabetes,[19] for lymphoma,[20] for prostate cancer,[21] for obesity,[22] for testicular cancer,[23] for breast cancer.[24]

An epidemiological study conducted by the National Cancer Institute reported that higher levels of chlordane in dust on the floors of homes were associated with higher rates of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in occupants.[25] Breathing chlordane in indoor air is the main route of exposure for these levels in human tissues. Currently, EPA has defined a concentration of 24 nanogram per cubic meter of air (ng/M3) for chlordane compounds over a 20-year exposure period as the concentration that will increase the probability of cancer by 1 in 1,000,000 persons. This probability of developing cancer increases to 10 in 1,000,000 persons with an exposure of 100 ng/m3 and 100 in 1,000,000 with an exposure of 1000 ng/m3.[26]

The non-cancer health effects of chlordane compounds, which include diabetes, insulin resistance, migraines, respiratory infections, immune-system activation, anxiety, depression, blurry vision, confusion, intractable seizures as well as permanent neurological damage,[27] probably affects more people than cancer. Trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane in serum of mothers during gestation has been linked with behaviors associated with autism in offspring at age 4–5.[28] The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) has defined a concentration of chlordane compounds of 20 ng/m3 as the Minimal Risk Level (MRLs). ATSDR defines Minimal Risk Level as an estimate of daily human exposure to a dose of a chemical that is likely to be without an appreciable risk of adverse non-cancerous effects over a specific duration of exposure.[29]

Remediation

[edit]Chlordane was applied under the home/building during treatment for termites and the half-life can be up to 30 years. Chlordane has a low vapor pressure and volatilizes slowly into the air of home/building above. To remove chlordane from indoor air requires either ventilation (Heat Exchange Ventilation) or activated carbon filtration. Chemical remediation of chlordane in soils was attempted by the US Army Corps of Engineers by mixing chlordane with aqueous lime and persulfate. In a phytoremediation study, Kentucky bluegrass and Perennial ryegrass were found to be minimally affected by chlordane, and both were found to take it up into their roots and shoots.[30] Mycoremediation of chlordane in soil have found that contamination levels were reduced.[30] The fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium has been found to reduce concentrations of chlordane by 21% in water in 30 days and in solids in 60 days.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0112". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Sigma-Aldrich Co., Chlordane (technical mixture). Retrieved on 2022-03-17.

- ^ "Chlordane". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- ^ Toxicological Profile for Chlordane, U.S. Department Of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

- ^ a b Robert L. Metcalf "Insect Control" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_263

- ^ a b Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxic Substances Portal: Chlordane. Last updated September, 2010 [online]. Available at URL: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/index.aspx?toxid=62

- ^ Dearth Mark A.; Hites Ronald A. (1991). "Complete analysis of technical chlordane using negative ionization mass spectrometry". Environ. Sci. Technol. 25 (2): 245–254. Bibcode:1991EnST...25..245D. doi:10.1021/es00014a005.

- ^ a b c Bondy, G. S.; Newsome, WH; Armstrong, CL; Suzuki, CA; Doucet, J; Fernie, S; Hierlihy, SL; Feeley, MM; Barker, MG (2000). "Trans-Nonachlor and cis-Nonachlor Toxicity in Sprague-Dawley Rats: Comparison with Technical Chlordane". Toxicological Sciences. 58 (2): 386–98. doi:10.1093/toxsci/58.2.386. PMID 11099650.

- ^ Liu W.; Ye J.; Jin M. (2009). "Enantioselective phytoeffects of chiral pesticides". J Agric Food Chem. 57 (6): 2087–2095. Bibcode:2009JAFC...57.2087L. doi:10.1021/jf900079y. PMID 19292458.

- ^ Pesticides and Breast Cancer Risk: Chlordane Archived 2012-06-14 at the Wayback Machine, Fact Sheet #11, March 1998, Program on Breast Cancer and Environmental Risk Factors Cornell University

- ^ Bennett, G. W.; Ballee, D. L.; Hall, R. C.; Fahey, J. F.; Butts, W. L. & Osmun, J. V. (1974). "Persistence and distribution of chlordane and dieldrin applied as termiticides". Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 11 (1): 64–9. Bibcode:1974BuECT..11...64B. doi:10.1007/BF01685030. PMID 4433785. S2CID 19893147.

- ^ Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (ATSDR). ToxFaqs: September, 1995. Available at URL: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tfacts31.pdf

- ^ Whitmore R. W.; et al. (1994). "Non-occupational exposures to pesticides for residents of two U.S. cities". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 26 (1): 47–59. Bibcode:1994ArECT..26...47W. doi:10.1007/bf00212793. PMID 8110023. S2CID 24736329.

- ^ Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Chemical Information: Chlordane. Last updated November, 2010 [online].

- ^ Lee D.; et al. (2007). "Association between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and insulin resistance among nondiabetic adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Diabetes Care. 30 (3): 622–628. doi:10.2337/dc06-2190. PMID 17327331.

- ^ "ORGANIC (LTD) | PESTICIDES | Chlorodane |". Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Kavita Singh, Wim J.M. Hegeman, Remi W.P.M. Laane, Hing Man Chan (2016). "Review and evaluation of a chiral enrichment model for chlordane enantiomers in the environment". Environmental Reviews. 24 (4): 363–376. doi:10.1139/er-2016-0015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The 12 initial POPs under the Stockholm Convention

- ^ Evangelou, E; et al. (2016). "Exposure to pesticides and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Environment International. 91: 60–68. Bibcode:2016EnInt..91...60E. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.013. PMID 26909814.

- ^ Luo, Dan; et al. (2005). "Exposure to organochlorine pesticides and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Scientific Reports. 6 25768. doi:10.1038/srep25768. PMC 4869027. PMID 27185567.

- ^ Lim, J.E.; et al. (2015). "Body concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and prostate cancer". Environmental Science Pullution Research International. 22 (15): 11275–84. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-4315-z. PMID 25797015. S2CID 207274251.

- ^ Tang-Peronard, J. L.; et al. (2011). "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and obesity development in humans: a review". Obesity Reviews. 12 (8): 622–36. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2011.00871.x. PMID 21457182. S2CID 33272647.

- ^ Cook, Michael B; et al. (2011). "Organochlorine compounds and testicular dysgenesis syndrome: human data". International Journal of Andrology. 34 (4): e68 – e85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01171.x. PMC 3145030. PMID 21668838.

- ^ Khanjani, Narges; et al. (2007). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of cylodiene insecticides and breast cancer". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C. 25 (1): 23–52. Bibcode:2007JESHC..25...23K. doi:10.1080/10590500701201711. PMID 17365341. S2CID 5563053.

- ^ Colt Joanna S.; et al. (2006). "Residential Insecticde Use and Risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (2): 251–257. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0556. PMID 16492912.

- ^ Chlordane (Technical) (CASRN 12789-03-6) | IRIS | US EPA

- ^ ATSDR - Medical Management Guidelines (MMGs): Chlordane

- ^ J. M. Braun (2014). "Gestational Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Reciprocal Social, Repetitive, and Stereotypic Behaviors in 4-and 5-Year-Old Children:The HOME Study". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (5): 513–520. Bibcode:2014EnvHP.122..513B. doi:10.1289/ehp.1307261. PMC 4014765. PMID 24622245.

- ^ ATSDR - Redirect - Toxicological Profile: Chlordane

- ^ a b Medina, Victor F.; Scott A. Waisner; Agnes B. Morrow; Afrachanna D. Butler; David R. Johnson; Allyson Harrison; Catherine C. Nestler. "Legacy Chlordane in Soils from Housing Areas Treated with Organochlorine Pesticides" (PDF). US Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Kennedy, D.W.; S. D. Aust; J. A. Bumpus (1990). "Comparative biodegradation of alkyl halide insecticides by the White Rot fungus, Phanerochaete chrysosporium". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2347–2353.

External links

[edit]Chlordane

View on GrokipediaChlordane is a synthetic organochlorine insecticide, appearing as a thick, colorless to amber liquid with a mild, irritating odor, composed primarily of the stereoisomers cis-chlordane (α-chlordane) and trans-chlordane (γ-chlordane), along with related chlorinated hydrocarbons and byproducts.[1][2][3] Developed in the 1940s and introduced commercially around 1945, chlordane served as a broad-spectrum contact pesticide effective against soil insects, agricultural pests, ants, and termites, with widespread applications in crop protection, lawn treatments, and subterranean structural barriers until regulatory restrictions curtailed its use.[4][5] Its environmental persistence—resisting degradation for decades in soil and sediments—combined with high lipophilicity enabling bioaccumulation and biomagnification through food chains, alongside toxicity manifesting as acute neurological symptoms (tremors, convulsions) and chronic effects (liver damage, probable carcinogenicity), prompted the U.S. EPA to cancel all registrations in 1988, following earlier limitations on non-termite uses in 1983.[4][6][7][8]

Chemical Properties and Composition

Molecular Structure and Isomers

Technical chlordane consists of a complex mixture of more than 25 chlorinated hydrocarbon compounds derived from the cyclodiene family, with the primary active ingredients being the stereoisomers cis-chlordane (α-chlordane, CAS 5103-71-9) and trans-chlordane (γ-chlordane, CAS 5103-74-2).[9] These two isomers typically account for 60-85% of the technical product, present in roughly equal proportions, alongside minor components such as heptachlor, chlordene, and cis- and trans-nonachlor.[10][11] The core molecular structure of chlordane is C₁₀H₆Cl₈, characterized by a bridged bicyclic norbornene-like framework with eight chlorine atoms attached to the carbon skeleton, specifically at positions forming a 1,2,4-metheno-2,3,4,7,7-pentachloro-1H-indene derivative.[12] The cis and trans isomers differ in the stereochemical configuration of the chlorine substituents relative to the molecular bridges, with cis-chlordane featuring the endo-exo orientation and trans-chlordane the exo-exo arrangement.[13] This stereoisomerism arises from the rigidity of the caged structure, leading to distinct spatial distributions that can influence reactivity, such as differential susceptibility to epoxidation or dechlorination pathways.[14] Heptachlor, a related precursor compound (C₁₀H₅Cl₇), often comprises up to 10-20% of technical chlordane and shares a similar hexachlorohexahydro-4,7-methanoindene core, differing by one fewer chlorine atom.[15] The presence of these structural variants contributes to the mixture's overall chemical heterogeneity, where the stereoisomers' configurations affect molecular stability, with the trans form generally exhibiting greater thermodynamic stability due to minimized steric interactions.[16]Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Technical chlordane, the commercial formulation, is a viscous liquid ranging in color from colorless to amber, with a density of 1.59–1.63 g/cm³ at 25°C.[4][17] Pure chlordane compounds form white solids or eutectic mixtures that remain liquid at room temperature, exhibiting low volatility characterized by a vapor pressure below 1 × 10⁻⁵ mmHg at 25°C.[18] Its high lipophilicity is indicated by an octanol-water partition coefficient (log Kow) of 5.54–6.16.[10][19] Chlordane demonstrates low aqueous solubility, approximately 0.009 mg/L at 25°C, which contributes to its limited mobility in water.[20] It is highly soluble in organic solvents such as hexane and acetone but resists hydrolysis under neutral or acidic conditions and shows minimal photodegradation in environmental matrices like soil or water surfaces.[21][22] Under typical environmental conditions, chlordane exhibits chemical stability, with persistence in soil varying by type: half-lives of about 4 years in general soils but exceeding 20 years in heavy, clayey, or organic-rich soils due to strong adsorption to organic matter.[23][24]| Property | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Water solubility | 0.009 mg/L | 25°C [20] |

| log Kow | 5.54–6.16 | Estimated/pure [10][19] |

| Soil half-life | 4–>20 years | Varies by soil type[23][24] |

Historical Development and Production

Invention and Commercialization

Chlordane was developed in the laboratories of Velsicol Chemical Corporation during the 1940s as a broad-spectrum insecticide, discovered by chemist Julius Hyman while exploring applications for chlorinated hydrocarbon byproducts.[20] The compound, a mixture primarily consisting of chlorinated cyclodiene isomers, emerged from efforts to create effective pest control agents amid post-World War II agricultural demands.[25] Velsicol, founded in 1931, prioritized innovation in organochlorine chemicals, positioning chlordane as a versatile alternative to earlier insecticides like DDT.[26] Commercial production of technical chlordane commenced in the United States in 1947, marking the onset of large-scale manufacturing by Velsicol at facilities including those in Chicago and later Memphis.[20][27] Initial formulations targeted soil-dwelling insects, capitalizing on chlordane's persistence and contact toxicity, which proved superior for subterranean applications compared to less stable predecessors.[9] Federal registration followed in 1948 under the U.S. Department of Agriculture's oversight (preceding the EPA's formation), approving uses in agriculture, livestock, and household settings, including termite control around building foundations.[22][28] Adoption accelerated rapidly due to demonstrated efficacy against pests such as termites, cutworms, and grubs, with chlordane integrated into crop protection and structural treatments by the early 1950s.[20] U.S. production escalated through the 1960s, reaching a peak of 9.5 million kilograms in 1974, reflecting widespread reliance on the insecticide for both commercial agriculture and residential applications before emerging environmental concerns prompted scrutiny.[9][29] This growth underscored chlordane's economic value in reducing crop losses and structural damage, though it also highlighted Velsicol's dominant market position in cyclodiene pesticides.[30]Manufacturing Processes and Scale

Chlordane is produced industrially via a sequential chlorination process starting with cyclopentadiene. Cyclopentadiene undergoes exhaustive chlorination to hexachlorocyclopentadiene, which then reacts with additional cyclopentadiene in a Diels-Alder cycloaddition to form chlordene. This intermediate is further chlorinated under controlled conditions, typically involving liquid-phase reactions at elevated temperatures, to yield technical chlordane as a viscous, isomeric mixture predominantly consisting of cis- and trans-octachloro-4,7-methano-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydroindane derivatives, alongside heptachlor and other coproducts.[31][9][32] The manufacturing process demands precise control of chlorine addition to minimize unwanted byproducts and achieve the target composition of 60-75% octachloro isomers in technical-grade material, with the remainder including lower chlorinated impurities like heptachlor epoxide precursors. This scalability stems from the availability of inexpensive chlorinating agents and the robustness of continuous-flow chlorination reactors, enabling efficient heat dissipation from exothermic reactions.[31][33] In the United States, production was dominated by Velsicol Chemical Corporation, reaching a peak of 9,500 metric tons in 1974 before declining due to regulatory pressures. Cumulative U.S. output contributed the majority of an estimated global total exceeding 70,000 metric tons by the late 1980s, after which domestic manufacturing ceased following the 1988 phase-out, with limited production shifting to other nations lacking equivalent restrictions. The process's cost-effectiveness, driven by high yields from commodity feedstocks, supported annual volumes sufficient for widespread agricultural distribution.[29][31][34]Applications and Efficacy

Primary Uses in Pest Control

Chlordane was primarily employed as a soil insecticide for the control of subterranean termites (Reticulitermes spp.) in structural protection, with applications involving subsurface treatments around building foundations to create protective barriers against termite infestation.[20] From its commercial introduction in 1948 until regulatory restrictions in 1978, it was also widely used against soil-dwelling pests in agricultural settings, including crops such as corn, vegetables, small grains, maize, oilseeds, and potatoes, as well as in lawns and orchards.[4][35] In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that chlordane treatments were applied to approximately 19.5 million structures for termite prevention prior to its phase-out for this purpose in 1988.[36] Common application methods for termite control included trenching along foundations, rodding into soil, subslab injection beneath structures, and low-pressure spraying to saturate soil zones.[37] For broader soil pest management, it was typically applied as surface sprays or incorporated into soil via mixing or irrigation.[20] Formulations most frequently used were emulsifiable concentrates, which allowed dilution in water for spray or injection delivery, alongside dusts, granules, and wettable powders for varied deployment.[38] These approaches leveraged chlordane's contact and stomach poison properties to target pests in their subterranean habitats.[4] In certain pest control niches, chlordane served as a persistent alternative to earlier broad-spectrum insecticides like DDT, particularly where extended residual soil activity was required for underground insect suppression, filling gaps left by DDT's limitations in deep soil penetration.[39]Performance Data and Economic Benefits

Chlordane exhibited strong efficacy against subterranean termites through both toxic and repellent mechanisms, forming persistent soil barriers that prevented structural infestations for 17 to 21 years in long-term field evaluations of treatments applied at various concentrations.[40] In comparative assessments, chlordane maintained control for up to 33 years, outperforming alternatives that required reapplication within shorter periods, such as a fraction of that duration.[41] This longevity reduced the frequency of interventions, providing economic advantages by averting annual U.S. termite damage costs, which exceeded billions of dollars in property repairs and reinforcements for untreated or inadequately protected structures.[42] In cost terms, chlordane's application minimized expenditures on repeated treatments and emergency remediation, as its superior persistence lowered lifetime protection costs relative to less durable substitutes available prior to restrictions.[41] A 1983 risk-benefit evaluation concluded that the pesticide's role in preventing high-cost infestations justified its use despite health concerns, given the substantial financial burden of termite-induced relocations, rebuilds, and insurance claims.[43] For agricultural pest control, chlordane safeguarded yields from soil insects in crops like corn, citrus, strawberries, and vegetables, with analyses indicating that its replacement would elevate costs and reduce output; a 1971 projection estimated $1.84 million in combined impacts from higher alternative insecticide expenses ($1.56 million) and yield shortfalls ($0.28 million) across treated U.S. acreage.[44] Specific losses included $31 per acre in citrus and $75 per acre in strawberries due to inferior efficacy of substitutes like diazinon, underscoring chlordane's value in sustaining productivity and farm revenues before phase-outs.[44]Regulatory Framework and Restrictions

Timeline of Approvals and Bans

Chlordane received initial registration as a pesticide by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1948.[22][4] Agricultural applications were deregistered in 1978, limiting uses primarily to structural pest control such as termite treatments.[45] In 1983, the EPA canceled all remaining registrations except for termite control.[1][46] The final cancellation of termite uses occurred on April 14, 1988, prohibiting all commercial production, sale, and application in the United States.[4][1] In the European Economic Community, chlordane faced restrictions under Council Directive 79/117/EEC, which banned its marketing and use effective January 1, 1981.[47] Similar prohibitions emerged across other European nations throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, with agricultural and broad-spectrum applications curtailed by the mid-1970s in several countries.[27] On the international level, chlordane was listed as one of the initial 12 persistent organic pollutants under the Stockholm Convention, adopted in 2001 and entering into force in 2004, mandating global elimination of production and use subject to registered specific exemptions for certain parties.[48] Phasedown of stockpiles continued in developing regions post-2001; for instance, China completed elimination of chlordane production and use by 2012 under Convention-supported programs.[49] Limited exceptions persist in some jurisdictions for research or waste management, while export from banning countries has been restricted under related treaties like the Rotterdam Convention.[50]Rationales and International Variations

The primary rationales for restricting chlordane centered on its environmental persistence, high bioaccumulation potential in fatty tissues, and observed toxicity to wildlife, which prompted phased cancellations in major markets despite limited direct evidence of widespread human harm from typical exposures.[4][23] Animal studies demonstrated carcinogenic effects, including liver tumors in rodents at doses relevant to chronic low-level exposure, leading regulators to classify it as a probable human carcinogen under precautionary frameworks, even as human epidemiological data showed only weak associations with cancers like non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[29] This application of precaution prioritized potential ecological risks over definitive human causation, with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decisions emphasizing buildup in food chains and non-target species impacts over robust occupational cohort outcomes.[4][36] Regulatory variations reflect differing balances between pest control needs and risk thresholds, with stricter measures in North America and Europe driven by advanced monitoring of wildlife bioaccumulation, contrasted by more permissive allowances in regions facing acute termite pressures. In the United States, cancellations progressed from agricultural uses in 1978 to a full ban by April 1988, citing indoor air contamination in treated homes and ecosystem loading; similar timelines applied in Canada and Mexico, culminating in North American elimination via a 1990s regional action plan.[46][50] The European Union incorporated chlordane into persistent organic pollutant (POP) controls under the Stockholm Convention by 2001, enforcing zero-tolerance production and use to mitigate transboundary deposition, while Japan restricted it to termite applications before a 1986 prohibition.[27][29] In contrast, select tropical and subtropical nations have retained restricted applications for structural termite control and wood preservation, where high pest infestation rates and limited infrastructure amplify economic losses from untreated infestations, though global enforcement under the Prior Informed Consent (PIC) regime has curbed unrestricted trade since the 1990s.[51] Critics highlight enforcement inconsistencies, noting that while developed regions phased out chlordane amid viable alternatives like pyrethroids, these substitutes face growing insect resistance—evident in reduced efficacy against subterranean termites—and may require higher application volumes, potentially offsetting persistence advantages.[52][53] Such disparities underscore debates on whether uniform bans overlook context-specific benefits, as chlordane's broad-spectrum knockdown remained superior for certain soil-dwelling pests despite its drawbacks.[54]Environmental Behavior and Effects

Persistence, Mobility, and Bioaccumulation

Chlordane exhibits substantial persistence in soil, where half-lives range from 2 to 20 years under varying environmental conditions, with residues remaining detectable in the upper layers for over 20 years.[18] This longevity stems from resistance to rapid degradation, as the compound's chlorinated structure limits microbial breakdown, favoring slow processes like microbial activity and photolysis that produce metabolites such as oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor.[18] In moist soils, volatilization contributes to initial losses, with half-lives of 2–3 days reported, though overall dissipation remains protracted.[18][38] Mobility of chlordane in the subsurface is low, attributed to strong sorption to soil organic matter and particles, evidenced by organic carbon partition coefficients (Koc) spanning 1,000–76,000 L/kg (mean log Koc ≈6.3 for trans-chlordane).[18] Its low aqueous solubility (0.056 mg/L) further restricts leaching, classifying it as a nonleacher that predominantly resides in topsoil.[18] Nonetheless, transport to groundwater occurs indirectly via surface runoff or adsorption to suspended particulates during erosion events.[18] Bioaccumulation of chlordane is pronounced due to its lipophilicity (log Kow 5.54–5.6), yielding bioconcentration factors (BCF) in aquatic organisms from 100 to 18,500, including 3,000–12,000 in marine species and up to 18,500 in rainbow trout.[18] This affinity for lipid tissues promotes uptake from water and subsequent biomagnification along food webs, as metabolic clearance is inefficient in many species.[18] Despite low volatility (vapor pressure 5.8×10⁻⁷ to 2.9×10⁻⁵ mmHg), chlordane undergoes atmospheric transport from treated surfaces, facilitating detections in remote areas like the Arctic at trace levels (≤0.0054 ng/m³).[18] Photolysis and hydroxyl radical reactions limit atmospheric residence to about 1.3 days, yet repeated volatilization and long-range advection enable global dispersal.[18][56]Impacts on Ecosystems and Wildlife

Chlordane demonstrates high acute toxicity to fish, with median lethal concentrations (LC50) reported at 0.07–0.09 mg/L for species such as bluegill sunfish and rainbow trout.[22] It is similarly toxic to aquatic invertebrates, including crustaceans and insects, through direct exposure or bioaccumulation in food chains, leading to disrupted aquatic ecosystems where residues persist in sediments.[57] For birds, chlordane exhibits moderate acute toxicity, with an oral LD50 of 83 mg/kg in species like mallards, though field observations document poisoning incidents, such as in six songbird and four raptor species in New Jersey from 1996–1997, attributed to soil and prey contamination causing neurological symptoms and mortality.[22][58] Bioaccumulation of chlordane and its metabolites, such as oxychlordane, occurs readily in fatty tissues of fish, birds, and mammals, magnifying exposure risks across trophic levels independent of its persistence.[18] This has resulted in ongoing fish consumption advisories in regions with legacy contamination, such as Illinois waterways, where residues in species like carp exceed safe thresholds for human consumers, indirectly signaling sustained ecological pressure on predatory wildlife.[59] Unlike DDT, which directly inhibits calcium deposition leading to eggshell thinning, empirical data do not strongly link chlordane to this effect in birds, though correlated organochlorine burdens have been noted in affected populations.[60] In terrestrial ecosystems, chlordane disrupts soil microbial communities by altering taxonomic composition and functional genes, as observed in laboratory exposures affecting bacterial diversity and earthworm gut microbiomes.[61] It also impacts invertebrate populations, reducing nematode abundances and earthworm viability without broadly halting decomposition processes, based on field and microcosm studies.[62] Population-level effects include localized declines in sensitive invertebrates and fish communities near application sites, with monitoring data post-1988 U.S. ban showing residue reductions—such as in northern gannet eggs—and partial recovery in bioaccumulation trends, though full ecosystem restoration lags in heavily contaminated areas due to slow degradation.[60] These outcomes stem from verified field poisonings and toxicity assays rather than solely predictive models, highlighting causal neurotoxic and enzymatic disruptions over generalized risk projections.[57][58]Human Health Considerations

Exposure Pathways and Toxicology

Chlordane exposure in humans occurs primarily through inhalation of vapors or dust during pesticide application or in treated structures, dermal contact with contaminated soil or equipment, and incidental ingestion via food chains or direct soil/dust consumption.[18] Occupational settings historically involved higher risks via inhalation and dermal routes during manufacturing, formulation, and termite control applications.[18] The compound is lipophilic and readily absorbed across inhalation, oral, and dermal routes, with gastrointestinal and respiratory uptake occurring efficiently in animal models and inferred for humans from biomonitoring data.[18] Post-absorption, chlordane distributes preferentially to the liver and kidneys initially, followed by bioaccumulation in adipose tissue, reflecting its affinity for fatty compartments.[18] Hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P-450 enzymes converts it primarily to persistent epoxides like oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor, which further accumulate in liver and fat.[18] Excretion is slow and predominantly fecal (70–90% in rodents, similar in humans), with minor lactation transfer; biological half-lives in human tissues range from approximately 20 days in adipose to 88 days overall.[18] Acute high-dose exposures induce central nervous system excitation, manifesting as tremors, ataxia, hypersensitivity, and convulsions in both human case reports and animal studies, with effects observed at oral doses as low as 0.15 mg/kg in humans and 200 mg/kg in rats.[18] This neurotoxicity arises from antagonism at GABA_A receptors, where chlordane blocks chloride ion channels, reducing inhibitory neurotransmission and promoting neuronal hyperexcitability, as demonstrated in rat brain assays and consistent with organochlorine pesticide mechanisms.[18][63]Evidence from Animal and Human Studies

In animal studies, technical chlordane exhibits moderate acute oral toxicity, with LD50 values ranging from 200 to 590 mg/kg in rats, depending on sex and formulation, and dermal LD50 values around 840 mg/kg in male rats.[9][20] High-dose oral or inhalation exposures in rodents and other mammals induce central nervous system effects such as tremors, convulsions, and ataxia, alongside gastrointestinal distress and respiratory failure.[7] Pathological findings include liver enlargement with fatty degeneration, subserosal hemorrhages, and splenic congestion.[20] Chronic animal exposures to chlordane at lower doses (e.g., 5-25 mg/kg/day in rats) reveal hepatotoxicity, evidenced by hepatocellular hypertrophy, peroxisome proliferation, and elevated liver enzyme levels, without consistent progression to overt failure at environmentally relevant levels.[18] Reproductive and developmental effects, such as reduced fertility, fetal resorption, and skeletal anomalies, occur primarily at high doses exceeding 10 mg/kg/day in rodents and rabbits, often confounded by maternal toxicity.[18] No clear thresholds for these non-neoplastic effects emerge below dietary concentrations of 10 ppm in multi-generational studies.[9] Human data derive mainly from acute poisoning incidents and limited occupational monitoring, with no large-scale controlled trials. Case reports of intentional or accidental ingestions (doses >1 g) describe neurologic symptoms including myoclonus, paresthesia, muscle twitching, diplopia, ataxia, and convulsions, alongside nausea, vomiting, and coma in severe cases, resolving with supportive care like gastric lavage and benzodiazepines.[36][4] Subacute home exposures via termite treatments have linked to neuropsychological deficits, such as impaired memory and executive function, in small cohorts, though causality is obscured by co-exposures and self-reporting.[64] Occupational cohorts exposed to chlordane aerosols (0.001-0.002 mg/m³ over 1-15 years) show no consistent non-cancer health deficits, with normal liver function tests and absence of neurologic sequelae in follow-ups.[20] Retrospective studies of pesticide workers report mixed associations with fatigue or irritability, but lack dose-response gradients and controls for confounders like smoking or other solvents.[7] Extrapolating animal findings to humans is challenged by orders-of-magnitude differences between experimental doses (often >100 mg/kg) and typical background exposures (<0.01 µg/kg/day via diet), yielding uncertain minimal effect levels.[18]Assessment of Carcinogenic Risk

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classifies chlordane as a Group B2 probable human carcinogen, a determination primarily based on sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in animal studies demonstrating increased incidences of liver tumors in mice and male rats following oral exposure.[65] The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) categorizes chlordane as Group 2B, possibly carcinogenic to humans, reflecting limited evidence in humans but sufficient evidence in experimental animals, including hepatocellular adenomas and carcinomas in B6C3F1 mice administered doses of 10–64 mg/kg/day in feed for 80 weeks.[27] These classifications rely on high-dose rodent bioassays where tumor promotion, rather than direct initiation, appears dominant, as chlordane induces cytochrome P450 enzymes and cell proliferation akin to non-genotoxic agents like phenobarbital.[66] Human epidemiological data provide weak and equivocal support for carcinogenicity, with most case-control and cohort studies failing to establish consistent associations due to unquantified exposures, confounding from pesticide mixtures, and lifestyle factors.[7] For instance, registry-based analyses of pesticide applicators showed no elevated risks for leukemia or multiple myeloma linked to chlordane use, while a study of breast cancer reported inconsistent odds ratios without dose-response trends.[4] No large-scale cohort studies demonstrate clear causal links, and occupational exposure assessments often conflate chlordane with co-applied organochlorines, limiting attribution.[66] Mechanistic investigations indicate chlordane functions predominantly as a tumor promoter in two-stage models, enhancing preneoplastic lesions initiated by genotoxic agents like N-nitrosodiethylamine in mouse liver, without evidence of direct DNA reactivity or mutagenicity in standard assays.[27] This promoter role, involving sustained hepatocyte proliferation and enzyme induction at doses far exceeding environmental levels, supports arguments for potential thresholds below which risks approach background rates from natural dietary carcinogens or endogenous processes, though regulatory models assume linearity absent human thresholds data.[67] Species differences—tumors in mice but not rats—and lack of genotoxicity underscore uncertainties in extrapolating to humans, where endocrine-modulating effects may contribute indirectly but remain unproven for oncogenesis.[66]Remediation Strategies

Techniques for Contaminated Sites

Excavation followed by off-site incineration or secure landfilling represents a primary technique for addressing high-concentration chlordane hotspots in soil, effectively removing bulk residues from sites exceeding regulatory thresholds such as 1.4 µg/g for remediation standards.[68] This method has been applied under CERCLA frameworks at contaminated industrial facilities, where physical removal prevents further leaching into groundwater, though it requires careful handling to minimize dust and volatilization during transport.[69] In situ chemical oxidation, particularly using persulfate activators, targets persistent chlordane fractions by generating sulfate radicals that cleave chlorinated bonds, with laboratory evaluations on legacy soils showing partial degradation rates of up to 50% under optimized conditions.[70] Alkaline hydrolysis has also been tested as a complementary approach, hydrolyzing chlordane into less toxic metabolites, though efficacy diminishes in heterogeneous soils due to uneven oxidant distribution.[70] Bioremediation employs microbial consortia, such as actinobacteria strains (e.g., Streptomyces spp.), to degrade chlordane via dechlorination and ring cleavage enzymes, achieving nearly 90% reduction in controlled slurry bioreactor systems over 28-60 days when combined with biostimulation nutrients.[71] Landfarming techniques, integrating bioaugmentation with indigenous soil microbes, have demonstrated 70-85% removal in field trials for pesticide-contaminated matrices, though slower rates apply to aged, sorbed residues.[72] Phytoremediation trials utilize hyperaccumulator plants like Populus tomentosa to enhance rhizosphere degradation of organochlorine pesticides, including chlordane analogs, with pilot-scale studies reporting 20-40% concentration reductions over one growing season through uptake and microbial stimulation, albeit with variable success tied to soil pH and organic matter.[73] EPA Superfund case studies, such as those involving pesticide production sites, highlight combined excavation-bioremediation approaches yielding 80-95% overall contaminant mass removal, though efficacy varies by site hydrogeology, with incomplete degradation of recalcitrant isomers necessitating post-treatment monitoring.[71] [74] For legacy termite-treated soils at former Air Force bases, monitoring protocols involve systematic surface and subsurface sampling to delineate plumes, often revealing concentrations from 22 to 2,540 ppm near foundations, coupled with volatilization flux assessments using forced-air chambers to evaluate inhalation risks prior to remediation decisions.[75] [4] These protocols, mandated under base closure regulations, guide risk-based thresholds for intervention, emphasizing long-term groundwater surveillance.[70]Effectiveness and Ongoing Challenges

Remediation efforts for chlordane-contaminated soils have demonstrated variable success, with bioremediation techniques achieving reductions of up to 56% in γ-chlordane concentrations over 28 days in aerobic soil assays using indigenous microorganisms.[76] Slurry-bioreactor systems augmented with Streptomyces consortia have shown promise in enhancing removal efficiency from polluted soils, though specific quantitative outcomes depend on site conditions such as initial concentrations and treatment duration.[77] Thermal desorption and excavation methods at legacy sites, like military housing areas, have reduced chlordane levels significantly over short-term treatments, sometimes meeting preliminary goals of 1-3.3 mg/kg in processed soils.[70] However, these approaches often fall short of complete elimination, with residual concentrations persisting due to chlordane's strong adsorption to organic carbon, clay, and silt particles, limiting desorption and further degradation.[70] Despite remediation, chlordane's environmental persistence—exceeding 30 years in soils and sediments—results in ongoing detections in aquatic systems and biota decades after its 1988 U.S. ban, including in fish tissues where legacy contaminants remain measurable.[36][78] Slow recovery in areas like San Francisco Bay underscores incomplete remediation outcomes, as bound residues in sediments continue to bioaccumulate in wildlife, evading full clearance even after bans and interventions.[79] Key challenges include high costs and scalability limitations for advanced techniques like bioaugmentation, which require site-specific optimization and may not economically apply to large-area contaminations.[80] Recontamination risks arise from incomplete removal or migration from untreated adjacent zones, complicating verification of cleanup goals such as EPA screening levels below 1 mg/kg, where analytical detection limits and heterogeneous soil binding hinder confirmation of non-detect status.[70] Natural attenuation analogs, like background organochlorines, further obscure low-level assessments, necessitating repeated monitoring to ensure long-term efficacy. Recent advances in the 2020s include bioaugmented slurry-bioreactors for targeted chlordane degradation, offering improved control over microbial consortia for higher efficiency in contained systems.[77] Nano-bioremediation approaches, integrating nanomaterials with biological agents, have emerged for persistent pesticides like chlordane, enhancing degradation rates through increased surface area and reactivity, though field-scale validation remains limited.[81] These innovations address binding challenges but face hurdles in regulatory approval and cost for widespread deployment.Debates and Alternative Viewpoints

Weighing Benefits Against Risks

Chlordane's primary benefit in termite control stemmed from its long residual efficacy, which provided protection against subterranean termites for decades after application, significantly reducing structural damage to wooden building elements such as foundations, framing, and floors. Introduced in 1948, it was applied to over 30 million homes in the United States, preventing widespread infestations that historically caused extensive property losses prior to effective chemical interventions; for instance, termite-related damages were estimated at hundreds of millions annually by the early 1980s even with controls in place, implying far greater unmitigated costs in earlier decades when options were limited to mechanical barriers or short-lived treatments.[82][83] This residual persistence outperformed alternatives like chlorpyrifos or lindane, which required more frequent re-applications and incurred at least twice the pest control costs for equivalent efficacy.[41] Observed human health risks from typical residential applications remained low despite the scale of use, with acute incidents—such as gastrointestinal distress or neurological symptoms like tremors—primarily linked to accidental high-dose exposures rather than standard subsurface treatments, and no evidence of widespread epidemics or elevated cancer clusters attributable to routine applications across millions of treated structures.[4][7] Modeled risks, often extrapolated from high-dose animal studies showing hepatic effects or carcinogenicity in rodents, projected potential long-term harms including endocrine disruption, yet empirical data from human epidemiology indicated minimal incidence, contrasting with regulatory emphases on persistence-driven bioaccumulation.[18] In comparison, unregulated termite proliferation without such controls could exacerbate invasive species spread and necessitate costlier physical repairs or less durable alternatives, potentially shifting burdens to untreated properties. Cost-benefit assessments, such as a 1983 industry analysis, concluded that chlordane's protective value against termite-induced structural failures—estimated to save billions in avoided damages over decades—outweighed projected health and environmental costs, particularly given the pesticide's targeted application and low volatility in soil.[43] Industry stakeholders, including pest control operators, highlighted these economic advantages and superior performance over post-ban substitutes, arguing for continued use under refined protocols, while regulators prioritized precautionary models of chronic exposure despite sparse confirmatory human data.[30] This divergence underscores a tension between observable, quantified benefits in property preservation and hypothetical risks amplified by persistence, with empirical low-incidence patterns suggesting overestimation in some hazard projections.[41]Critiques of Regulatory Overreach

Critics of chlordane regulation contend that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) decisions exemplified precautionary overreach, extrapolating risks from high-dose animal studies to human policy despite limited epidemiological support. Chlordane produced liver tumors in mice at doses far exceeding typical human exposures, but human evidence remains equivocal, consisting of mixed case-control results and insufficient cohort data to establish causality for cancer or other systemic effects.[84] [59] The EPA's classification as a probable human carcinogen relies predominantly on rodent bioassays, with thresholds for no-observed-adverse-effect levels (NOAELs) in animals suggesting margins of safety that precautionary bans disregarded in favor of zero-tolerance assumptions.[4] This approach overlooked chlordane's demonstrated utility in subsurface termite control and crop protection, where its persistence enabled long-term efficacy and reduced application frequency compared to alternatives. Post-ban replacements, such as chlorpyrifos for termiticide uses, exhibited higher acute mammalian toxicity, potentially amplifying short-term exposure risks during more frequent reapplications.[51] Economic analyses indicated elevated costs for structural treatments and agricultural pest management, straining productivity in regions reliant on effective, low-volume insecticides for food security.[85] A 1980 Government Accountability Office (GAO) review criticized the EPA for not performing a formal risk-benefit analysis prior to restricting chlordane, noting that continued termite uses were approved administratively rather than through balanced evaluation of benefits against mitigated risks.[86] Proponents of risk-based tolerances argue this omission favored hazard-based prohibitions, amplifying animal-derived concerns into policy without accounting for exposure gradients or societal trade-offs, such as increased termite damage to infrastructure estimated in billions annually pre-ban. International disparities further highlight potential overreaction, as nations with delayed phase-outs under the Stockholm Convention reported no disproportionate health catastrophes attributable to chlordane persistence, underscoring the need for context-specific thresholds over uniform global restrictions.[87]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/229977309_Chlordane_transport_in_a_sandy_soil_Effects_of_suspended_soil_material_and_pig_slurry