Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Recursion (computer science)

View on Wikipedia

In computer science, recursion is a method of solving a computational problem where the solution depends on solutions to smaller instances of the same problem.[1][2] Recursion solves such recursive problems by using functions that call themselves from within their own code. The approach can be applied to many types of problems, and recursion is one of the central ideas of computer science.[3]

The power of recursion evidently lies in the possibility of defining an infinite set of objects by a finite statement. In the same manner, an infinite number of computations can be described by a finite recursive program, even if this program contains no explicit repetitions.

— Niklaus Wirth, Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs, 1976[4]

Most computer programming languages support recursion by allowing a function to call itself from within its own code. Some functional programming languages (for instance, Clojure)[5] do not define any looping constructs but rely solely on recursion to repeatedly call code. It is proved in computability theory that these recursive-only languages are Turing complete; this means that they are as powerful (they can be used to solve the same problems) as imperative languages based on control structures such as while and for.

Repeatedly calling a function from within itself may cause the call stack to have a size equal to the sum of the input sizes of all involved calls. It follows that, for problems that can be solved easily by iteration, recursion is generally less efficient, and, for certain problems, algorithmic or compiler-optimization techniques such as tail call optimization may improve computational performance over a naive recursive implementation.[citation needed]

History

[edit]The development of recursion in computer science grew out of mathematical logic and later became an essential part of programming language design.[6] The early work done by Church, Gödel, Kleene, and Turing on recursive function and computability laid the groundwork that made recursion possible in programming languages.[6] Recursion has been used by mathematicians for a long time, but it only became a practical tool for programming in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[7] Key figures such as John McCarthy and the ALGOL 60 design committee contributed to introducing recursion into programming.[7]

John McCarthy took the first steps by creating the programming language LISP in 1960.[8] In his paper Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I, McCarthy showed that recursion could be core in a programming language that works with symbols by processing them step by step.[8] In LISP, recursion could be used in functions using simple rules, and there was also a way to evaluate them in the language.[8] This demonstrated that recursion was a practical way to write programs and that it also describes the process of computation.[6] Therefore, LISP became one of the first programming languages to use recursion as a main feature, and later on also influenced other languages that followed.[7]

During that time, recursion was also added to ALGOL 60.[9] The Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 60, which was published in 1960, was the outcome of an international attempt at designing a standard language.[9] Allowing procedures to call themselves was one of the new important features of the language.[7] Before that, only loops were allowed to be used by programmers, so it was a significant change.[7] Recursion allowed programmers to describe algorithms in a more natural and flexible way.[7] Therefore, recursion was seen as something theoretically important and practically useful by computer scientists.[7]

C. A. R. Hoare demonstrated another way where recursion could be useful when he introduced the Quicksort algorithm in 1961.[10] Quicksort uses a divide-and-conquer method, by breaking an array into smaller parts and recursively sorting each piece until the whole array is sorted.[10] Hoare’s algorithm gave an example of how recursion could be an efficient solution to problems.[10] Later on, Quicksort became one of the most widely used sorting algorithms and is still being taught to upcoming computer scientists.[11] The success of the algorithm showed that recursion is not just a conceptual idea but is a useful technique that solves real problems.[11]

All these contributions from these major computer scientists helped convert recursion from a mathematical idea to an important part of programming.[7] To this day, it continues to play an important role in education and practice.[12] A 2021 study comparing recursion and iteration in problem solving determined that recursion remains central in the way computer science is taught, as it provides a new way of thinking about problems that iteration does not provide.[12]

Structure of a recursive function

[edit]The definition of a recursive function is typically divided into two parts: one or more base case(s) and one or more recursive case(s).[13] This structure mirrors the logic of mathematical induction, which is a proof technique where proving the base case(s) and the inductive step ensures that a given theorem holds for all valid inputs.

Base case

[edit]The base case specifies input values for which the function can provide a result directly, without any further recursion.[14] These are typically the simplest or smallest possible inputs (which can be solved trivially), allowing a computation to terminate. Base cases are essential because they prevent infinite regress. In other words, they define a stopping condition that terminates the recursion.

An example is computing the factorial of an integer n, which is the product of all integers from 0 to n. For this problem, the definition 0! = 1 is a base case. Without it, the recursion may continue indefinitely, leading to non-termination or even stack overflow errors in actual implementations.

Designing a correct base case is crucial for both theoretical and practical reasons. Some problems have a natural base case (e.g., the empty list is a base case in some recursive list-processing functions), while others require an additional parameter to provide a stopping criterion (e.g., using a depth counter in recursive tree traversal).

In recursive computer programming, omitting the base case or defining it incorrectly may result in unintended infinite recursion. In a study, researchers showed that many students struggle to identify appropriate base cases [14].

Recursive case

[edit]The recursive case describes how to break down a problem into smaller sub-problems of the same form[14]. Each recursive step transforms the input so that it approaches a base case, ensuring progress toward termination. If the reduction step fails to progress toward a base case, the algorithm can get trapped in an infinite loop.

In the factorial example, the recursive case is defined as:

n! = n * (n-1)!, n > 0

Here, each invocation of the function decreases the input n by 1. Thus, it ensures that the recursion eventually reaches the base case of n = 0.

The recursive case is analogous to the inductive step in a proof by induction: it assumes that the function works for a smaller instance and then extends this assumption to the current input. Recursive definitions and algorithms thus closely parallel inductive arguments in mathematics, and their correctness often relies on similar reasoning techniques.

Examples

[edit]There are several practical applications of recursion that follow the base case and recursive case structure. These are widely used to solve complex problems in computer science.

- Tree traversals, such as depth-first search, use a recursive case to process each subtree (the recursive case), eventually stopping at leaf nodes (the base case).[15]

- Merge sort is a sorting algorithm that recursively sorts and merges divided subarrays (the recursive case) until each subarray consists of one element (the base case).[16]

- Fibonacci sequence is defined by summing the two previous numbers in the sequence (the recursive case), stopping when n = 0 or n = 1 (the base cases).

- Binary search repeatedly divides the search interval in half (recursive case) until the target is found or the interval is empty (base cases).

Recursive data types

[edit]Many computer programs must process or generate an arbitrarily large quantity of data. Recursion is a technique for representing data whose exact size is unknown to the programmer: the programmer can specify this data with a self-referential definition. There are two types of self-referential definitions: inductive and coinductive definitions.

Inductively defined data

[edit]An inductively defined recursive data definition is one that specifies how to construct instances of the data. For example, linked lists can be defined inductively (here, using Haskell syntax):

data ListOfStrings = EmptyList | Cons String ListOfStrings

The code above specifies a list of strings to be either empty, or a structure that contains a string and a list of strings. The self-reference in the definition permits the construction of lists of any (finite) number of strings.

Another example of inductive definition is the natural numbers (or positive integers):

A natural number is either 1 or n+1, where n is a natural number.

Similarly recursive definitions are often used to model the structure of expressions and statements in programming languages. Language designers often express grammars in a syntax such as Backus–Naur form; here is such a grammar, for a simple language of arithmetic expressions with multiplication and addition:

<expr> ::= <number>

| (<expr> * <expr>)

| (<expr> + <expr>)

This says that an expression is either a number, a product of two expressions, or a sum of two expressions. By recursively referring to expressions in the second and third lines, the grammar permits arbitrarily complicated arithmetic expressions such as (5 * ((3 * 6) + 8)), with more than one product or sum operation in a single expression.

Coinductively defined data and corecursion

[edit]A coinductive data definition is one that specifies the operations that may be performed on a piece of data; typically, self-referential coinductive definitions are used for data structures of infinite size.

A coinductive definition of infinite streams of strings, given informally, might look like this:

A stream of strings is an object s such that: head(s) is a string, and tail(s) is a stream of strings.

This is very similar to an inductive definition of lists of strings; the difference is that this definition specifies how to access the contents of the data structure—namely, via the accessor functions head and tail—and what those contents may be, whereas the inductive definition specifies how to create the structure and what it may be created from.

Corecursion is related to coinduction, and can be used to compute particular instances of (possibly) infinite objects. As a programming technique, it is used most often in the context of lazy programming languages, and can be preferable to recursion when the desired size or precision of a program's output is unknown. In such cases the program requires both a definition for an infinitely large (or infinitely precise) result, and a mechanism for taking a finite portion of that result. The problem of computing the first n prime numbers is one that can be solved with a corecursive program (e.g. here).

Types of recursion

[edit]Single recursion and multiple recursion

[edit]Recursion that contains only a single self-reference is known as single recursion, while recursion that contains multiple self-references is known as multiple recursion. Standard examples of single recursion include list traversal, such as in a linear search, or computing the factorial function, while standard examples of multiple recursion include tree traversal, such as in a depth-first search.

Single recursion is often much more efficient than multiple recursion, and can generally be replaced by an iterative computation, running in linear time and requiring constant space. Multiple recursion, by contrast, may require exponential time and space, and is more fundamentally recursive, not being able to be replaced by iteration without an explicit stack.

Multiple recursion can sometimes be converted to single recursion (and, if desired, thence to iteration). For example, while computing the Fibonacci sequence naively entails multiple iteration, as each value requires two previous values, it can be computed by single recursion by passing two successive values as parameters. This is more naturally framed as corecursion, building up from the initial values, while tracking two successive values at each step – see corecursion: examples. A more sophisticated example involves using a threaded binary tree, which allows iterative tree traversal, rather than multiple recursion.

Indirect recursion

[edit]Most basic examples of recursion, and most of the examples presented here, demonstrate direct recursion, in which a function calls itself. Indirect recursion occurs when a function is called not by itself but by another function that it called (either directly or indirectly). For example, if f calls f, that is direct recursion, but if f calls g which calls f, then that is indirect recursion of f. Chains of three or more functions are possible; for example, function 1 calls function 2, function 2 calls function 3, and function 3 calls function 1 again.

Indirect recursion is also called mutual recursion, which is a more symmetric term, though this is simply a difference of emphasis, not a different notion. That is, if f calls g and then g calls f, which in turn calls g again, from the point of view of f alone, f is indirectly recursing, while from the point of view of g alone, it is indirectly recursing, while from the point of view of both, f and g are mutually recursing on each other. Similarly a set of three or more functions that call each other can be called a set of mutually recursive functions.

Anonymous recursion

[edit]Recursion is usually done by explicitly calling a function by name. However, recursion can also be done via implicitly calling a function based on the current context, which is particularly useful for anonymous functions, and is known as anonymous recursion.

Structural versus generative recursion

[edit]Some authors classify recursion as either "structural" or "generative". The distinction is related to where a recursive procedure gets the data that it works on, and how it processes that data:

[Functions that consume structured data] typically decompose their arguments into their immediate structural components and then process those components. If one of the immediate components belongs to the same class of data as the input, the function is recursive. For that reason, we refer to these functions as (STRUCTURALLY) RECURSIVE FUNCTIONS.

— Felleisen, Findler, Flatt, and Krishnaurthi, How to Design Programs, 2001[17]

Thus, the defining characteristic of a structurally recursive function is that the argument to each recursive call is the content of a field of the original input. Structural recursion includes nearly all tree traversals, including XML processing, binary tree creation and search, etc. By considering the algebraic structure of the natural numbers (that is, a natural number is either zero or the successor of a natural number), functions such as factorial may also be regarded as structural recursion.

Generative recursion is the alternative:

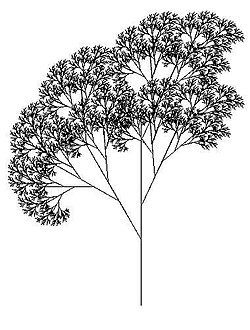

Many well-known recursive algorithms generate an entirely new piece of data from the given data and recur on it. HtDP (How to Design Programs) refers to this kind as generative recursion. Examples of generative recursion include: gcd, quicksort, binary search, mergesort, Newton's method, fractals, and adaptive integration.

— Matthias Felleisen, Advanced Functional Programming, 2002[18]

This distinction is important in proving termination of a function.

- All structurally recursive functions on finite (inductively defined) data structures can easily be shown to terminate, via structural induction: intuitively, each recursive call receives a smaller piece of input data, until a base case is reached.

- Generatively recursive functions, in contrast, do not necessarily feed smaller input to their recursive calls, so proof of their termination is not necessarily as simple, and avoiding infinite loops requires greater care. These generatively recursive functions can often be interpreted as corecursive functions – each step generates the new data, such as successive approximation in Newton's method – and terminating this corecursion requires that the data eventually satisfy some condition, which is not necessarily guaranteed.

- In terms of loop variants, structural recursion is when there is an obvious loop variant, namely size or complexity, which starts off finite and decreases at each recursive step.

- By contrast, generative recursion is when there is not such an obvious loop variant, and termination depends on a function, such as "error of approximation" that does not necessarily decrease to zero, and thus termination is not guaranteed without further analysis.

Implementation issues

[edit]In actual implementation, rather than a pure recursive function (single check for base case, otherwise recursive step), a number of modifications may be made, for purposes of clarity or efficiency. These include:

- Wrapper function (at top)

- Short-circuiting the base case, aka "Arm's-length recursion" (at bottom)

- Hybrid algorithm (at bottom) – switching to a different algorithm once data is small enough

On the basis of elegance, wrapper functions are generally approved, while short-circuiting the base case is frowned upon, particularly in academia. Hybrid algorithms are often used for efficiency, to reduce the overhead of recursion in small cases, and arm's-length recursion is a special case of this.

Wrapper function

[edit]A wrapper function is a function that is directly called but does not recurse itself, instead calling a separate auxiliary function which actually does the recursion.

Wrapper functions can be used to validate parameters (so the recursive function can skip these), perform initialization (allocate memory, initialize variables), particularly for auxiliary variables such as "level of recursion" or partial computations for memoization, and handle exceptions and errors. In languages that support nested functions, the auxiliary function can be nested inside the wrapper function and use a shared scope. In the absence of nested functions, auxiliary functions are instead a separate function, if possible private (as they are not called directly), and information is shared with the wrapper function by using pass-by-reference.

Short-circuiting the base case

[edit]

| Ordinary recursion | Short-circuit recursion |

|---|---|

int fac1(int n) {

if (n <= 0)

return 1;

else

return fac1(n-1)*n;

}

|

int fac2(int n) {

// assert(n >= 2);

if (n == 2)

return 2;

else

return fac2(n-1)*n;

}

int fac2wrapper(int n) {

if (n <= 1)

return 1;

else

return fac2(n);

}

|

Short-circuiting the base case, also known as arm's-length recursion, consists of checking the base case before making a recursive call – i.e., checking if the next call will be the base case, instead of calling and then checking for the base case. Short-circuiting is particularly done for efficiency reasons, to avoid the overhead of a function call that immediately returns. Note that since the base case has already been checked for (immediately before the recursive step), it does not need to be checked for separately, but one does need to use a wrapper function for the case when the overall recursion starts with the base case itself. For example, in the factorial function, properly the base case is 0! = 1, while immediately returning 1 for 1! is a short circuit, and may miss 0; this can be mitigated by a wrapper function. The box shows C code to shortcut factorial cases 0 and 1.

Short-circuiting is primarily a concern when many base cases are encountered, such as Null pointers in a tree, which can be linear in the number of function calls, hence significant savings for O(n) algorithms; this is illustrated below for a depth-first search. Short-circuiting on a tree corresponds to considering a leaf (non-empty node with no children) as the base case, rather than considering an empty node as the base case. If there is only a single base case, such as in computing the factorial, short-circuiting provides only O(1) savings.

Conceptually, short-circuiting can be considered to either have the same base case and recursive step, checking the base case only before the recursion, or it can be considered to have a different base case (one step removed from standard base case) and a more complex recursive step, namely "check valid then recurse", as in considering leaf nodes rather than Null nodes as base cases in a tree. Because short-circuiting has a more complicated flow, compared with the clear separation of base case and recursive step in standard recursion, it is often considered poor style, particularly in academia.[19]

Depth-first search

[edit]A basic example of short-circuiting is given in depth-first search (DFS) of a binary tree; see binary trees section for standard recursive discussion.

The standard recursive algorithm for a DFS is:

- base case: If current node is Null, return false

- recursive step: otherwise, check value of current node, return true if match, otherwise recurse on children

In short-circuiting, this is instead:

- check value of current node, return true if match,

- otherwise, on children, if not Null, then recurse.

In terms of the standard steps, this moves the base case check before the recursive step. Alternatively, these can be considered a different form of base case and recursive step, respectively. Note that this requires a wrapper function to handle the case when the tree itself is empty (root node is Null).

In the case of a perfect binary tree of height h, there are 2h+1−1 nodes and 2h+1 Null pointers as children (2 for each of the 2h leaves), so short-circuiting cuts the number of function calls in half in the worst case.

In C, the standard recursive algorithm may be implemented as:

bool tree_contains(struct node *tree_node, int i) {

if (tree_node == NULL)

return false; // base case

else if (tree_node->data == i)

return true;

else

return tree_contains(tree_node->left, i) ||

tree_contains(tree_node->right, i);

}

The short-circuited algorithm may be implemented as:

// Wrapper function to handle empty tree

bool tree_contains(struct node *tree_node, int i) {

if (tree_node == NULL)

return false; // empty tree

else

return tree_contains_do(tree_node, i); // call auxiliary function

}

// Assumes tree_node != NULL

bool tree_contains_do(struct node *tree_node, int i) {

if (tree_node->data == i)

return true; // found

else // recurse

return (tree_node->left && tree_contains_do(tree_node->left, i)) ||

(tree_node->right && tree_contains_do(tree_node->right, i));

}

Note the use of short-circuit evaluation of the Boolean && (AND) operators, so that the recursive call is made only if the node is valid (non-Null). Note that while the first term in the AND is a pointer to a node, the second term is a Boolean, so the overall expression evaluates to a Boolean. This is a common idiom in recursive short-circuiting. This is in addition to the short-circuit evaluation of the Boolean || (OR) operator, to only check the right child if the left child fails. In fact, the entire control flow of these functions can be replaced with a single Boolean expression in a return statement, but legibility suffers at no benefit to efficiency.

Hybrid algorithm

[edit]Recursive algorithms are often inefficient for small data, due to the overhead of repeated function calls and returns. For this reason efficient implementations of recursive algorithms often start with the recursive algorithm, but then switch to a different algorithm when the input becomes small. An important example is merge sort, which is often implemented by switching to the non-recursive insertion sort when the data is sufficiently small, as in the tiled merge sort. Hybrid recursive algorithms can often be further refined, as in Timsort, derived from a hybrid merge sort/insertion sort.

Recursion versus iteration

[edit]Recursion and iteration are equally expressive: recursion can be replaced by iteration with an explicit call stack, while iteration can be replaced with tail recursion. Which approach is preferable depends on the problem under consideration and the language used. In imperative programming, iteration is preferred, particularly for simple recursion, as it avoids the overhead of function calls and call stack management, but recursion is generally used for multiple recursion. By contrast, in functional languages recursion is preferred, with tail recursion optimization leading to little overhead. Implementing an algorithm using iteration may not be easily achievable.

Compare the templates to compute xn defined by xn = f(n, xn-1) from xbase:

function recursive(n)

if n == base

return xbase

else

return f(n, recursive(n - 1))

|

function iterative(n)

x = xbase

for i = base + 1 to n

x = f(i, x)

return x

|

For an imperative language the overhead is to define the function, and for a functional language the overhead is to define the accumulator variable x.

For example, a factorial function may be implemented iteratively in C by assigning to a loop index variable and accumulator variable, rather than by passing arguments and returning values by recursion:

unsigned int factorial(unsigned int n) {

unsigned int product = 1; // empty product is 1

while (n) {

product *= n;

--n;

}

return product;

}

Expressive power

[edit]Most programming languages in use today allow the direct specification of recursive functions and procedures. When such a function is called, the program's runtime environment keeps track of the various instances of the function (often using a call stack, although other methods may be used). Every recursive function can be transformed into an iterative function by replacing recursive calls with iterative control constructs and simulating the call stack with a stack explicitly managed by the program.[20][21]

Conversely, all iterative functions and procedures that can be evaluated by a computer (see Turing completeness) can be expressed in terms of recursive functions; iterative control constructs such as while loops and for loops are routinely rewritten in recursive form in functional languages.[22][23] However, in practice this rewriting depends on tail call elimination, which is not a feature of all languages. C, Java, and Python are notable mainstream languages in which all function calls, including tail calls, may cause stack allocation that would not occur with the use of looping constructs; in these languages, a working iterative program rewritten in recursive form may overflow the call stack, although tail call elimination may be a feature that is not covered by a language's specification, and different implementations of the same language may differ in tail call elimination capabilities.

Performance issues

[edit]In languages (such as C and Java) that favor iterative looping constructs, there is usually significant time and space cost associated with recursive programs, due to the overhead required to manage the stack and the relative slowness of function calls; in functional languages, a function call (particularly a tail call) is typically a very fast operation, and the difference is usually less noticeable.

As a concrete example, the difference in performance between recursive and iterative implementations of the "factorial" example above depends highly on the compiler used. In languages where looping constructs are preferred, the iterative version may be as much as several orders of magnitude faster than the recursive one. In functional languages, the overall time difference of the two implementations may be negligible; in fact, the cost of multiplying the larger numbers first rather than the smaller numbers (which the iterative version given here happens to do) may overwhelm any time saved by choosing iteration.

Stack space

[edit]In some programming languages, the maximum size of the call stack is much less than the space available in the heap, and recursive algorithms tend to require more stack space than iterative algorithms. Consequently, these languages sometimes place a limit on the depth of recursion to avoid stack overflows; Python is one such language.[24] Note the caveat below regarding the special case of tail recursion.

Vulnerability

[edit]Because recursive algorithms can be subject to stack overflows, they may be vulnerable to pathological or malicious input.[25] Some malware specifically targets a program's call stack and takes advantage of the stack's inherently recursive nature.[26] Even in the absence of malware, a stack overflow caused by unbounded recursion can be fatal to the program, and exception handling logic may not prevent the corresponding process from being terminated.[27]

Multiply recursive problems

[edit]Multiply recursive problems are inherently recursive, because of prior state they need to track. One example is tree traversal as in depth-first search; though both recursive and iterative methods are used,[28] they contrast with list traversal and linear search in a list, which is a singly recursive and thus naturally iterative method. Other examples include divide-and-conquer algorithms such as Quicksort, and functions such as the Ackermann function. All of these algorithms can be implemented iteratively with the help of an explicit stack, but the programmer effort involved in managing the stack, and the complexity of the resulting program, arguably outweigh any advantages of the iterative solution.

Refactoring recursion

[edit]Recursive algorithms can be replaced with non-recursive counterparts.[29] One method for replacing recursive algorithms is to simulate them using heap memory in place of stack memory.[30] An alternative is to develop a replacement algorithm entirely based on non-recursive methods, which can be challenging.[31] For example, recursive algorithms for matching wildcards, such as Rich Salz' wildmat algorithm,[32] were once typical. Non-recursive algorithms for the same purpose, such as the Krauss matching wildcards algorithm, have been developed to avoid the drawbacks of recursion[33] and have improved only gradually based on techniques such as collecting tests and profiling performance.[34]

Tail-recursive functions

[edit]Tail-recursive functions are functions in which all recursive calls are tail calls and hence do not build up any deferred operations. For example, the gcd function (shown again below) is tail-recursive. In contrast, the factorial function (also below) is not tail-recursive; because its recursive call is not in tail position, it builds up deferred multiplication operations that must be performed after the final recursive call completes. With a compiler or interpreter that treats tail-recursive calls as jumps rather than function calls, a tail-recursive function such as gcd will execute using constant space. Thus the program is essentially iterative, equivalent to using imperative language control structures like the "for" and "while" loops.

| Tail recursion: | Augmenting recursion: |

|---|---|

//INPUT: Integers x, y such that x >= y and y >= 0

int gcd(int x, int y)

{

if (y == 0)

return x;

else

return gcd(y, x % y);

}

|

//INPUT: n is an Integer such that n >= 0

int fact(int n)

{

if (n == 0)

return 1;

else

return n * fact(n - 1);

}

|

The significance of tail recursion is that when making a tail-recursive call (or any tail call), the caller's return position need not be saved on the call stack; when the recursive call returns, it will branch directly on the previously saved return position. Therefore, in languages that recognize this property of tail calls, tail recursion saves both space and time.

Order of execution

[edit]Consider these two functions:

Function 1

[edit]void recursiveFunction(int num) {

printf("%d\n", num);

if (num < 4)

recursiveFunction(num + 1);

}

Function 2

[edit]void recursiveFunction(int num) {

if (num < 4)

recursiveFunction(num + 1);

printf("%d\n", num);

}

The output of function 2 is that of function 1 with the lines swapped.

In the case of a function calling itself only once, instructions placed before the recursive call are executed once per recursion before any of the instructions placed after the recursive call. The latter are executed repeatedly after the maximum recursion has been reached.

Also note that the order of the print statements is reversed, which is due to the way the functions and statements are stored on the call stack.

Recursive procedures

[edit]Factorial

[edit]A classic example of a recursive procedure is the function used to calculate the factorial of a natural number:

| Pseudocode (recursive): |

|---|

function factorial is: |

The function can also be written as a recurrence relation:

This evaluation of the recurrence relation demonstrates the computation that would be performed in evaluating the pseudocode above:

| Computing the recurrence relation for n = 4: |

|---|

b4 = 4 × b3

= 4 × (3 × b2)

= 4 × (3 × (2 × b1))

= 4 × (3 × (2 × (1 × b0)))

= 4 × (3 × (2 × (1 × 1)))

= 4 × (3 × (2 × 1))

= 4 × (3 × 2)

= 4 × 6

= 24

|

This factorial function can also be described without using recursion by making use of the typical looping constructs found in imperative programming languages:

| Pseudocode (iterative): |

|---|

function factorial is: |

The imperative code above is equivalent to this mathematical definition using an accumulator variable t:

The definition above translates straightforwardly to functional programming languages such as Scheme; this is an example of iteration implemented recursively.

Greatest common divisor

[edit]The Euclidean algorithm, which computes the greatest common divisor of two integers, can be written recursively.

Function definition:

| Pseudocode (recursive): |

|---|

function gcd is: input: integer x, integer y such that x > 0 and y >= 0 |

Recurrence relation for greatest common divisor, where expresses the remainder of :

- if

| Computing the recurrence relation for x = 27 and y = 9: |

|---|

gcd(27, 9) = gcd(9, 27 % 9)

= gcd(9, 0)

= 9

|

| Computing the recurrence relation for x = 111 and y = 259: |

gcd(111, 259) = gcd(259, 111 % 259)

= gcd(259, 111)

= gcd(111, 259 % 111)

= gcd(111, 37)

= gcd(37, 111 % 37)

= gcd(37, 0)

= 37

|

The recursive program above is tail-recursive; it is equivalent to an iterative algorithm, and the computation shown above shows the steps of evaluation that would be performed by a language that eliminates tail calls. Below is a version of the same algorithm using explicit iteration, suitable for a language that does not eliminate tail calls. By maintaining its state entirely in the variables x and y and using a looping construct, the program avoids making recursive calls and growing the call stack.

| Pseudocode (iterative): |

|---|

function gcd is: |

The iterative algorithm requires a temporary variable, and even given knowledge of the Euclidean algorithm it is more difficult to understand the process by simple inspection, although the two algorithms are very similar in their steps.

Towers of Hanoi

[edit]

The Towers of Hanoi is a mathematical puzzle whose solution illustrates recursion.[35][36] There are three pegs which can hold stacks of disks of different diameters. A larger disk may never be stacked on top of a smaller. Starting with n disks on one peg, they must be moved to another peg one at a time. What is the smallest number of steps to move the stack?

Function definition:

Recurrence relation for hanoi:

| Computing the recurrence relation for n = 4: |

|---|

hanoi(4) = 2×hanoi(3) + 1

= 2×(2×hanoi(2) + 1) + 1

= 2×(2×(2×hanoi(1) + 1) + 1) + 1

= 2×(2×(2×1 + 1) + 1) + 1

= 2×(2×(3) + 1) + 1

= 2×(7) + 1

= 15

|

Example implementations:

| Pseudocode (recursive): |

|---|

function hanoi is: |

Although not all recursive functions have an explicit solution, the Tower of Hanoi sequence can be reduced to an explicit formula.[37]

| An explicit formula for Towers of Hanoi: |

|---|

h1 = 1 = 21 - 1 h2 = 3 = 22 - 1 h3 = 7 = 23 - 1 h4 = 15 = 24 - 1 h5 = 31 = 25 - 1 h6 = 63 = 26 - 1 h7 = 127 = 27 - 1 In general: hn = 2n - 1, for all n >= 1 |

Binary search

[edit]The binary search algorithm is a method of searching a sorted array for a single element by cutting the array in half with each recursive pass. The trick is to pick a midpoint near the center of the array, compare the data at that point with the data being searched and then responding to one of three possible conditions: the data is found at the midpoint, the data at the midpoint is greater than the data being searched for, or the data at the midpoint is less than the data being searched for.

Recursion is used in this algorithm because with each pass a new array is created by cutting the old one in half. The binary search procedure is then called recursively, this time on the new (and smaller) array. Typically the array's size is adjusted by manipulating a beginning and ending index. The algorithm exhibits a logarithmic order of growth because it essentially divides the problem domain in half with each pass.

Example implementation of binary search in C:

/*

Call binary_search with proper initial conditions.

INPUT:

data is an array of integers SORTED in ASCENDING order,

toFind is the integer to search for,

count is the total number of elements in the array

OUTPUT:

result of binary_search

*/

int search(int *data, int toFind, int count)

{

// Start = 0 (beginning index)

// End = count - 1 (top index)

return binary_search(data, toFind, 0, count-1);

}

/*

Binary Search Algorithm.

INPUT:

data is a array of integers SORTED in ASCENDING order,

toFind is the integer to search for,

start is the minimum array index,

end is the maximum array index

OUTPUT:

position of the integer toFind within array data,

-1 if not found

*/

int binary_search(int *data, int toFind, int start, int end)

{

//Get the midpoint.

int mid = start + (end - start)/2; //Integer division

if (start > end) //Stop condition (base case)

return -1;

else if (data[mid] == toFind) //Found, return index

return mid;

else if (data[mid] > toFind) //Data is greater than toFind, search lower half

return binary_search(data, toFind, start, mid-1);

else //Data is less than toFind, search upper half

return binary_search(data, toFind, mid+1, end);

}

Recursive data structures (structural recursion)

[edit]An important application of recursion in computer science is in defining dynamic data structures such as lists and trees. Recursive data structures can dynamically grow to a theoretically infinite size in response to runtime requirements; in contrast, the size of a static array must be set at compile time.

"Recursive algorithms are particularly appropriate when the underlying problem or the data to be treated are defined in recursive terms."[38]

The examples in this section illustrate what is known as "structural recursion". This term refers to the fact that the recursive procedures are acting on data that is defined recursively.

As long as a programmer derives the template from a data definition, functions employ structural recursion. That is, the recursions in a function's body consume some immediate piece of a given compound value.[18]

Linked lists

[edit]Below is a C definition of a linked list node structure. Notice especially how the node is defined in terms of itself. The "next" element of struct node is a pointer to another struct node, effectively creating a list type.

struct node

{

int data; // some integer data

struct node *next; // pointer to another struct node

};

Because the struct node data structure is defined recursively, procedures that operate on it can be implemented naturally as recursive procedures. The list_print procedure defined below walks down the list until the list is empty (i.e., the list pointer has a value of NULL). For each node it prints the data element (an integer). In the C implementation, the list remains unchanged by the list_print procedure.

void list_print(struct node *list)

{

if (list != NULL) // base case

{

printf ("%d ", list->data); // print integer data followed by a space

list_print (list->next); // recursive call on the next node

}

}

Binary trees

[edit]Below is a simple definition for a binary tree node. Like the node for linked lists, it is defined in terms of itself, recursively. There are two self-referential pointers: left (pointing to the left sub-tree) and right (pointing to the right sub-tree).

struct node

{

int data; // some integer data

struct node *left; // pointer to the left subtree

struct node *right; // point to the right subtree

};

Operations on the tree can be implemented using recursion. Note that because there are two self-referencing pointers (left and right), tree operations may require two recursive calls:

// Test if tree_node contains i; return 1 if so, 0 if not.

int tree_contains(struct node *tree_node, int i) {

if (tree_node == NULL)

return 0; // base case

else if (tree_node->data == i)

return 1;

else

return tree_contains(tree_node->left, i) || tree_contains(tree_node->right, i);

}

At most two recursive calls will be made for any given call to tree_contains as defined above.

// Inorder traversal:

void tree_print(struct node *tree_node) {

if (tree_node != NULL) { // base case

tree_print(tree_node->left); // go left

printf("%d ", tree_node->data); // print the integer followed by a space

tree_print(tree_node->right); // go right

}

}

The above example illustrates an in-order traversal of the binary tree. A Binary search tree is a special case of the binary tree where the data elements of each node are in order.

Filesystem traversal

[edit]Since the number of files in a filesystem may vary, recursion is the only practical way to traverse and thus enumerate its contents. Traversing a filesystem is very similar to that of tree traversal, therefore the concepts behind tree traversal are applicable to traversing a filesystem. More specifically, the code below would be an example of a preorder traversal of a filesystem.

import java.io.File;

public class FileSystem {

public static void main(String [] args) {

traverse();

}

/**

* Obtains the filesystem roots

* Proceeds with the recursive filesystem traversal

*/

private static void traverse() {

File[] fs = File.listRoots();

for (int i = 0; i < fs.length; i++) {

System.out.println(fs[i]);

if (fs[i].isDirectory() && fs[i].canRead()) {

rtraverse(fs[i]);

}

}

}

/**

* Recursively traverse a given directory

*

* @param fd indicates the starting point of traversal

*/

private static void rtraverse(File fd) {

File[] fss = fd.listFiles();

for (int i = 0; i < fss.length; i++) {

System.out.println(fss[i]);

if (fss[i].isDirectory() && fss[i].canRead()) {

rtraverse(fss[i]);

}

}

}

}

This code is both recursion and iteration - the files and directories are iterated, and each directory is opened recursively.

The "rtraverse" method is an example of direct recursion, whilst the "traverse" method is a wrapper function.

The "base case" scenario is that there will always be a fixed number of files and/or directories in a given filesystem.

Time-efficiency of recursive algorithms

[edit]The time efficiency of recursive algorithms can be expressed in a recurrence relation of Big O notation. They can (usually) then be simplified into a single Big-O term.

Shortcut rule (master theorem)

[edit]If the time-complexity of the function is in the form

Then the Big O of the time-complexity is thus:

- If for some constant , then

- If , then

- If for some constant , and if for some constant c < 1 and all sufficiently large n, then

where a represents the number of recursive calls at each level of recursion, b represents by what factor smaller the input is for the next level of recursion (i.e. the number of pieces you divide the problem into), and f(n) represents the work that the function does independently of any recursion (e.g. partitioning, recombining) at each level of recursion.

Recursion in Logic Programming

[edit]In the procedural interpretation of logic programs, clauses (or rules) of the form A :- B are treated as procedures, which reduce goals of the form A to subgoals of the form B.

For example, the Prolog clauses:

path(X,Y) :- arc(X,Y).

path(X,Y) :- arc(X,Z), path(Z,Y).

define a procedure, which can be used to search for a path from X to Y, either by finding a direct arc from X to Y, or by finding an arc from X to Z, and then searching recursively for a path from Z to Y. Prolog executes the procedure by reasoning top-down (or backwards) and searching the space of possible paths depth-first, one branch at a time. If it tries the second clause, and finitely fails to find a path from Z to Y, it backtracks and tries to find an arc from X to another node, and then searches for a path from that other node to Y.

However, in the logical reading of logic programs, clauses are understood declaratively as universally quantified conditionals. For example, the recursive clause of the path-finding procedure is understood as representing the knowledge that, for every X, Y and Z, if there is an arc from X to Z and a path from Z to Y then there is a path from X to Y. In symbolic form:

The logical reading frees the reader from needing to know how the clause is used to solve problems. The clause can be used top-down, as in Prolog, to reduce problems to subproblems. Or it can be used bottom-up (or forwards), as in Datalog, to derive conclusions from conditions. This separation of concerns is a form of abstraction, which separates declarative knowledge from problem solving methods (see Algorithm#Algorithm = Logic + Control).[39]

Infinite recursion

[edit]A common mistake among programmers is not providing a way to exit a recursive function, often by omitting or incorrectly checking the base case, letting it run (at least theoretically) infinitely by endlessly calling itself recursively. This is called infinite recursion, and the program will never terminate. In practice, this typically exhausts the available stack space. In most programming environments, a program with infinite recursion will not really run forever. Eventually, something will break and the program will report an error.[40]

Below is a Java code that would use infinite recursion:

public class InfiniteRecursion {

static void recursive() { // Recursive Function with no way out

recursive();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

recursive(); // Executes the recursive function upon runtime

}

}

Running this code will result in a stack overflow error.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Graham, Ronald; Knuth, Donald; Patashnik, Oren (1990). "1: Recurrent Problems". Concrete Mathematics. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-55802-5.

- ^ Kuhail, Mohammad A.; Negreiros, Joao; Seffah, Ahmed (2021). "Teaching Recursive Thinking using Unplugged Activities". World Transactions on Engineering and Technology Education. 19 (2): 169–175.

- ^ Epp, Susanna (1995). Discrete Mathematics with Applications (2nd ed.). PWS Publishing Company. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-53494446-9.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (1976). Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs. Prentice-Hall. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-13022418-7.

- ^ "Functional Programming | Clojure for the Brave and True". www.braveclojure.com. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ a b c Soare, Robert I. (1996). "Computability and Recursion". Bulletin of Symbolic Logic. 2 (3): 284–321. doi:10.2307/420992. JSTOR 421008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Daylight, Edgar G. (2010). The Advent of Recursion in Programming, 1950s–1960s (Report). Preprint Series PP-2010-04. University of Amsterdam, Institute for Logic, Language and Computation.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, John (1960). "Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I". Communications of the ACM. 3 (4): 184–195. doi:10.1145/367177.367199.

- ^ a b Naur, Peter; John Backus; John McCarthy (1960). "Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 60". Communications of the ACM. 3 (5): 299–314. doi:10.1145/367236.367262.

- ^ a b c Hoare, C. A. R. (1961). "Quicksort". Communications of the ACM. 4 (7): 321–322. doi:10.1145/366622.366644.

- ^ a b Cormen, Thomas H.; Charles E. Leiserson; Ronald L. Rivest; Clifford Stein (2009). Introduction to Algorithms (3rd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03384-8.

- ^ a b Endres, Madeline; Westley Weimer; Amir Kamil (2021). "An Analysis of Iterative and Recursive Problem Performance". Proceedings of the 52nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE '21). Association for Computing Machinery. doi:10.1145/3408877.3432391.

- ^ Kong, Qingkai; Siauw, Timmy; Bayen, Alexandre M. (2021). "Recursion". Python Programming and Numerical Methods. pp. 105–120. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819549-9.00015-4. ISBN 978-0-12-819549-9.

- ^ a b c Sweigart, Al (2022). The Recursive Book of Recursion: Ace the Coding Interview with Python and JavaScript. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-7185-0202-4.[page needed]

- ^ Hopcroft, John; Tarjan, Robert (June 1973). "Algorithm 447: efficient algorithms for graph manipulation". Communications of the ACM. 16 (6): 372–378. doi:10.1145/362248.362272.

- ^ Bron, C. (May 1972). "Algorithm 426: Merge sort algorithm [M1]". Communications of the ACM. 15 (5): 357–358. doi:10.1145/355602.361317.

- ^ Felleisen et al. 2001, art V "Generative Recursion

- ^ a b Felleisen, Matthias (2002). "Developing Interactive Web Programs". In Jeuring, Johan (ed.). Advanced Functional Programming: 4th International School (PDF). Springer. p. 108. ISBN 9783540448334.

- ^ Mongan, John; Giguère, Eric; Kindler, Noah (2013). Programming Interviews Exposed: Secrets to Landing Your Next Job (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-118-26136-1.

- ^ Hetland, Magnus Lie (2010), Python Algorithms: Mastering Basic Algorithms in the Python Language, Apress, p. 79, ISBN 9781430232384.

- ^ Drozdek, Adam (2012), Data Structures and Algorithms in C++ (4th ed.), Cengage Learning, p. 197, ISBN 9781285415017.

- ^ Shivers, Olin. "The Anatomy of a Loop - A story of scope and control" (PDF). Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ^ Lambda the Ultimate. "The Anatomy of a Loop". Lambda the Ultimate. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ^ "27.1. sys — System-specific parameters and functions — Python v2.7.3 documentation". Docs.python.org. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ^ Krauss, Kirk J. (2014). "Matching Wildcards: An Empirical Way to Tame an Algorithm". Dr. Dobb's Journal.

- ^ Mueller, Oliver (2012). "Anatomy of a Stack Smashing Attack and How GCC Prevents It". Dr. Dobb's Journal.

- ^ "StackOverflowException Class". .NET Framework Class Library. Microsoft Developer Network. 2018.

- ^ "Depth First Search (DFS): Iterative and Recursive Implementation". Techie Delight. 2018.

- ^ Mitrovic, Ivan. "Replace Recursion with Iteration". ThoughtWorks.

- ^ La, Woong Gyu (2015). "How to replace recursive functions using stack and while-loop to avoid the stack-overflow". CodeProject.

- ^ Moertel, Tom (2013). "Tricks of the trade: Recursion to Iteration, Part 2: Eliminating Recursion with the Time-Traveling Secret Feature Trick".

- ^ Salz, Rich (1991). "wildmat.c". GitHub.

- ^ Krauss, Kirk J. (2008). "Matching Wildcards: An Algorithm". Dr. Dobb's Journal.

- ^ Krauss, Kirk J. (2018). "Matching Wildcards: An Improved Algorithm for Big Data". Develop for Performance.

- ^ Graham, Knuth & Patashnik 1990, §1.1: The Tower of Hanoi

- ^ Epp 1995, pp. 427–430: The Tower of Hanoi

- ^ Epp 1995, pp. 447–448: An Explicit Formula for the Tower of Hanoi Sequence

- ^ Wirth 1976, p. 127

- ^ Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter. (2021). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach §9.3, §9.4 (4th ed.). Hoboken: Pearson. ISBN 978-0134610993. LCCN 20190474.

- ^ "4.8. Infinite Recursion — How to Think Like a Computer Scientist - C++".

References

[edit]- Barron, David William (1968) [1967]. Written at Cambridge, UK. Gill, Stanley (ed.). Recursive techniques in programming. Macdonald Computer Monographs (1 ed.). London, UK: Macdonald & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. SBN 356-02201-3. (viii+64 pages)

- Felleisen, Matthias; Findler, Robert B.; Flatt, Matthew; Krishnamurthi, Shriram (2001). How To Design Programs: An Introduction to Computing and Programming. MIT Press. ISBN 0262062186.

- Rubio-Sanchez, Manuel (2017). Introduction to Recursive Programming. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-64717-5.

- Pevac, Irena (2016). Practicing Recursion in Java. CreateSpace Independent. ISBN 978-1-5327-1227-2.

- Roberts, Eric (2005). Thinking Recursively with Java. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-47170146-0.

- Rohl, Jeffrey S. (1984). Recursion Via Pascal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26934-6.

- Helman, Paul; Veroff, Robert. Walls and Mirrors.

- Abelson, Harold; Sussman, Gerald Jay; Sussman, Julie (1996). Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (2nd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-51087-1.

- Dijkstra, Edsger W. (1960). "Recursive Programming". Numerische Mathematik. 2 (1): 312–318. doi:10.1007/BF01386232. S2CID 127891023.

- McCarthy, John (1960). "Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I". Communications of the ACM. 3 (4): 184–195. doi:10.1145/367177.367199.

- Naur, Peter; John Backus; John McCarthy (1960). "Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 60". Communications of the ACM. 3 (5): 299–314. doi:10.1145/367236.367262.

- Hoare, C. A. R. (1961). "Quicksort". Communications of the ACM. 4 (7): 321–322. doi:10.1145/366622.366644.

- Soare, Robert I. (1996). "Computability and Recursion". Bulletin of Symbolic Logic. 2 (3): 284–321. doi:10.2307/420992. JSTOR 421008.

- Daylight, Edgar G. (2010). The Advent of Recursion in Programming, 1950s–1960s (Report). Preprint Series PP-2010-04. University of Amsterdam, Institute for Logic, Language and Computation.

- Endres, Madeline; Westley Weimer; Amir Kamil (2021). "An Analysis of Iterative and Recursive Problem Performance". Proceedings of the 52nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE '21). Association for Computing Machinery. doi:10.1145/3408877.3432391.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Charles E. Leiserson; Ronald L. Rivest; Clifford Stein (2009). Introduction to Algorithms (3rd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03384-8.

Recursion (computer science)

View on Grokipediafactorial(n) = n * factorial(n-1) with base case factorial(0) = 1), generating Fibonacci sequences, searching in binary trees, and solving problems such as the Tower of Hanoi puzzle or merge sort.[8][9] It excels in modeling natural recursive processes, like parsing nested data structures or graph traversals.[10]

While recursion can produce elegant, readable code that mirrors problem decomposition—particularly for divide-and-conquer paradigms—its drawbacks include higher runtime overhead from repeated function calls and potential stack overflow for deep recursions, making iteration preferable in performance-critical scenarios.[11][12] In practice, tail-recursive optimizations or explicit stack management mitigate these issues in many languages.[13]

The concept of recursion in computing traces its roots to early 20th-century mathematical logic, with foundational work by Kurt Gödel, Alonzo Church, and Alan Turing on recursive functions and computability, which influenced programming paradigms.[14] In practical programming, recursion emerged in the 1950s and 1960s through implementations in languages like Lisp and Algol, driven by needs in symbolic computation and algorithm design, independent of prior theoretical recursion in mathematics.[15]

Fundamentals of Recursion

Definition and Basic Concepts

In computer science, recursion refers to the idea of describing the solution of a problem in terms of solutions to simpler instances of the same problem.[2] This technique is commonly implemented in programming through a function that calls itself with modified arguments, enabling the breakdown of complex tasks into self-similar subtasks until a termination condition is reached.[2] Recursion contrasts with iterative approaches by emphasizing self-reference rather than explicit loops, promoting elegant solutions for problems with inherent hierarchical or repetitive structure.[1] The conceptual foundations of recursion trace back to mathematical logic, particularly Alonzo Church's development of lambda calculus in the early 1930s as a formal system for expressing computation via function abstraction and application.[16] Church's work, introduced in papers from 1932 and 1933, provided a theoretical basis for treating functions as computable entities, laying groundwork for recursive definitions in computability theory.[16] Recursion entered practical programming through John McCarthy's design of the Lisp language in 1958, where it became a core mechanism for symbolic computation and established recursion as a pillar of functional programming paradigms.[17] Understanding recursion requires familiarity with fundamental programming concepts, such as functions that accept parameters as inputs and produce return values as outputs to propagate results back through the call chain.[18] These elements allow recursive calls to build upon prior computations systematically. A generic structure for a recursive function in pseudocode illustrates this process, including a base case for termination and a recursive case for decomposition:function recursive_solve(problem):

if base_case(problem): // Termination condition

return direct_solution(problem)

else:

smaller_problem = reduce(problem)

sub_solution = recursive_solve(smaller_problem)

return combine(sub_solution, problem)

function recursive_solve(problem):

if base_case(problem): // Termination condition

return direct_solution(problem)

else:

smaller_problem = reduce(problem)

sub_solution = recursive_solve(smaller_problem)

return combine(sub_solution, problem)

Base Case and Recursive Case

In recursive functions within computer science, the structure is fundamentally divided into two components: the base case and the recursive case. The base case identifies the simplest form of the problem, where the function can compute and return a result directly without invoking further recursive calls, thereby ensuring the recursion terminates and averting infinite loops.[19] This termination condition is crucial, as it provides the foundation upon which all recursive computations build, mirroring the initial step in mathematical induction.[20] The recursive case, conversely, addresses more general or complex inputs by decomposing the problem into smaller subproblems, invoking the function itself with arguments that progressively simplify toward the base case. This self-referential step advances the computation by reducing the problem's size or complexity in each call, guaranteeing eventual convergence to the base case provided the reduction is well-defined.[21] Together, these cases form the dual structure that enables recursion to solve problems by breaking them down iteratively until trivial instances are reached.[22] A recursion tree offers a visual or textual representation of this process, depicting the initial call as the root and subsequent recursive calls as branching nodes, with leaves signifying base cases where computation halts. For instance, in a binary recursive structure, the tree might unfold as follows: Root (Recursive Case)

/ \

Left Subcall (Recursive) Right Subcall (Base Case)

/ \

Base Case Base Case

Root (Recursive Case)

/ \

Left Subcall (Recursive) Right Subcall (Base Case)

/ \

Base Case Base Case

Recursive Data Types

Inductively Defined Data

Inductive data types, also known as inductively defined types, form a cornerstone of recursive data modeling in computer science, particularly within type theory and functional programming languages. These types are constructed from a finite set of base constructors and recursive constructors, where the latter incorporate instances of the type itself to build more complex structures from simpler ones, ensuring that all values have finite size and no infinite nesting. This inductive approach mirrors the bottom-up construction of data, starting from atomic elements and progressively adding layers, which naturally aligns with recursive definitions that terminate due to the absence of cycles. A seminal example is the type of natural numbers, formalized via the Peano axioms, which define the naturals inductively as either the base element zero or the successor of another natural number. In type-theoretic notation, this is expressed as:inductive Nat : Type

| zero : Nat

| succ : Nat → Nat

inductive Nat : Type

| zero : Nat

| succ : Nat → Nat

zero acts as the base constructor, while succ recursively applies to any existing natural number to produce the next one, generating the sequence 0, 1 (succ zero), 2 (succ (succ zero)), and so on. This construction, originating from Giuseppe Peano's 1889 axiomatization and adapted in modern type theory, provides a rigorous foundation for arithmetic operations through recursive decomposition.[25][26]

Another fundamental example is the list type, which represents sequences of elements from a given type either as the empty list (nil) or as a non-empty list formed by cons-ing an element of with another list. Formally:

inductive List (A : Type) : Type

| nil : List A

| cons : A → List A → List A

inductive List (A : Type) : Type

| nil : List A

| cons : A → List A → List A

nil constructor provides the base, and cons enables recursive extension, allowing lists like cons 1 (cons 2 nil) to represent [1, 2]. This inductive definition, standard in languages like Haskell and theorem provers like Coq, facilitates the representation of variable-length collections built incrementally.

Recursion processes these inductive types through pattern matching on their constructors, which systematically dismantles the structure by cases: handling the base constructor directly and recursively invoking the function on substructures produced by recursive constructors. In Per Martin-Löf's intuitionistic type theory, this is supported by elimination rules that ensure recursive definitions respect the inductive structure, with the base case corresponding to the base constructor for termination. Such mechanisms enable principled computation over inductively defined data without risking non-termination.[26]

Coinductively Defined Data and Corecursion

Coinductive types provide a foundation for modeling infinite data structures in computer science, defined not by exhaustive construction but by infinite sequences of observations or behaviors that can be inspected indefinitely. These types are particularly useful for representing potentially unending computations or data flows, such as infinite streams or trees, where the structure unfolds without termination. For instance, an infinite stream can be viewed as a pair consisting of a head element and another stream as its tail, allowing observations like accessing the first element or advancing to the next. This observational approach ensures that coinductive types capture all possible infinite extensions compatible with the defined behaviors. Corecursion serves as the primary mechanism for defining and generating values of coinductive types, acting as the categorical dual to standard recursion on inductive types. In corecursion, a function produces an output structure through recursive calls that build the data incrementally, starting from an initial state and observing how it evolves. To prevent non-productive definitions that could lead to infinite loops without output, corecursive functions must adhere to productivity conditions: each recursive step must yield at least one observable component before recursing further, guaranteeing that approximations of the infinite structure can be computed finitely. This duality highlights how corecursion "unfolds" infinite data outward, in contrast to recursion's inward consumption of finite data.[27] A representative example appears in functional programming languages supporting laziness, such as Haskell, where corecursion enables concise definitions of infinite streams without explicit loops. Consider the stream of constant ones:ones = 1 : ones, where the list constructor : prepends 1 to the recursively defined tail. This definition is productive, as the head is immediately observable, and the tail advances the structure indefinitely. Formally, coinductive types arise as the greatest fixed point of a type functor, encompassing the largest set of behaviors closed under the observations, whereas inductively defined data correspond to the least fixed point, capturing only the minimal finite closures. This fixed-point distinction underpins the theoretical separation between finite and infinite structures in type theory.[28]

Types of Recursion

Direct, Indirect, and Anonymous Recursion

In direct recursion, a function invokes itself directly within its own body to solve a problem by breaking it down into smaller instances of the same task. This form is prevalent in algorithms like factorial computation or binary tree traversals, where the recursive call handles the subproblem while the base case terminates the process. For instance, a factorial function in pseudocode can be expressed as:function factorial(n):

if n <= 1:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial(n - 1)

function factorial(n):

if n <= 1:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial(n - 1)

function isEven(n):

if n == 0:

return true

else:

return isOdd(n - 1)

function isOdd(n):

if n == 0:

return false

else:

return isEven(n - 1)

function isEven(n):

if n == 0:

return true

else:

return isOdd(n - 1)

function isOdd(n):

if n == 0:

return false

else:

return isEven(n - 1)

Single, Multiple, and Structural Recursion

In computer science, recursion can be classified based on the number of recursive calls made per invocation and the manner in which the problem is decomposed. Single recursion occurs when a function makes exactly one recursive call to itself during each invocation, resulting in a linear execution tree where each node has at most one child.[35] This form is common in problems that reduce the input size by a fixed amount, such as computing the factorial of a number. For instance, the factorial functionfact(n) is defined as fact(n) = n * fact(n-1) for n > 0, with a base case fact(0) = 1, leading to a straightforward chain of calls: fact(5) calls fact(4), which calls fact(3), and so on until the base case.[35]

Multiple recursion, in contrast, involves a function making two or more recursive calls per invocation, often producing an exponential or branching execution tree.[35] This arises in problems requiring exploration of multiple subproblems simultaneously, such as the naive implementation of the Fibonacci sequence, where fib(n) = fib(n-1) + fib(n-2) for n > 1, with base cases fib(0) = 0 and fib(1) = 1. Here, computing fib(5) branches into calls for fib(4) and fib(3), each of which further branches, creating a tree with redundant computations.[35] While powerful for divide-and-conquer strategies, multiple recursion can lead to higher computational costs due to the branching factor.

Structural recursion refers to a style where the recursive calls directly mirror the structure of the input data, typically processing each component (e.g., elements or substructures) in a way that consumes the data inductively. This approach is well-suited for recursively defined data types like lists or trees, where the function recurses on subparts such as the first element and the rest of a list, or on left and right children of a tree node. For example, summing the elements of a list via structural recursion might define sum(lst) as 0 for an empty list, or first(lst) + sum(rest(lst)) otherwise, ensuring the recursion follows the list's linear structure exactly once per element. Structural recursion promotes systematic decomposition aligned with data representation, often resulting in single recursion for linear structures or multiple recursion for branched ones like binary trees.

Generative recursion, on the other hand, generates new subproblems through computation that does not necessarily follow the input's structure, instead creating instances of the original problem via transformations or searches.[36] Unlike structural recursion, which consumes data predictably, generative recursion often involves decisions that produce varying subproblem sizes or forms, requiring explicit termination arguments to ensure progress. A classic example is the quicksort algorithm, where partitioning an array around a pivot generates two subarrays (elements less than and greater than the pivot), on which the function recurses independently: quicksort(arr) selects a pivot, partitions the array, and recursively sorts the subarrays.[36] This generative process can lead to multiple recursive calls but is not tied to the data's inherent shape, making it ideal for optimization or search problems like finding a path in a graph.

The choice between these forms involves trade-offs in applicability and efficiency: structural recursion excels in data processing tasks where the input's form guides decomposition, ensuring completeness and avoiding redundancy, while generative recursion suits algorithmic searches or generations that require flexible problem reformulation, though it demands careful bounding to prevent non-termination.[36] In practice, indirect recursion—where functions call each other in a cycle—can incorporate single, multiple, structural, or generative patterns depending on the call graph.[35]

Implementation Techniques

Wrapper Functions and Short-Circuiting

Wrapper functions serve as non-recursive outer layers that initialize parameters for an underlying recursive helper function, providing a simplified interface while concealing implementation details such as accumulators or auxiliary arguments. This approach enhances code modularity and user-friendliness in recursive algorithms, particularly in functional programming paradigms where recursive definitions often require additional state tracking.[37] The worker/wrapper transformation formalizes this pattern, allowing refactoring of recursive programs to improve performance by converting lazy computations into stricter forms or incorporating accumulators that propagate results efficiently through the recursion.[38] For instance, in computing the sum of a list, the wrapper function initiates the recursion with an initial accumulator value of zero, avoiding the need for users to supply it explicitly and preventing errors from improper initialization. This technique is widely used to maintain clean APIs while optimizing internal recursive logic.[39] The following pseudocode illustrates a wrapper for a recursive list sum:function sum(elements):

if elements is empty:

return 0

return sum_helper(elements, 0)

function sum_helper(elements, accumulator):

if elements is empty:

return accumulator

else:

return sum_helper(elements.tail(), accumulator + elements.head())

function sum(elements):

if elements is empty:

return 0

return sum_helper(elements, 0)

function sum_helper(elements, accumulator):

if elements is empty:

return accumulator

else:

return sum_helper(elements.tail(), accumulator + elements.head())

sum function acts as the wrapper, handling the base case for empty inputs directly and delegating the accumulation to the helper.

Short-circuiting in recursive functions refers to the strategic placement of conditional checks—typically at the function's entry point—to detect base cases or termination conditions early, thereby avoiding unnecessary recursive invocations and pruning the computation tree. This practice directly enhances the base case mechanism by ensuring trivial or invalid inputs terminate immediately, reducing stack depth and computational overhead.[40]

In the sum example above, the initial check in the wrapper for an empty list exemplifies short-circuiting, as it returns zero without entering the helper recursion, efficiently handling the edge case. Similarly, within the helper, the empty-list check prunes further calls. Such early checks are crucial for efficiency in algorithms processing variable-sized inputs, preventing deep recursion on degenerate cases like empty structures.[39]

These techniques—wrappers for initialization and short-circuiting for termination—collectively improve code readability by separating concerns, bolster robustness against edge cases, and optimize performance by minimizing recursive depth where possible. In practice, they make recursive solutions more maintainable and less prone to stack overflow errors in languages without tail-call optimization.[37]

Hybrid Algorithms and Depth-First Search

Hybrid algorithms in computer science combine recursive and iterative techniques to leverage the clarity and natural structure of recursion while mitigating risks associated with deep call stacks, such as stack overflow in languages without tail call optimization.[41] This approach is particularly valuable in graph and tree traversals, where pure recursion elegantly simulates implicit stacks but can exceed available memory for large or deeply nested structures, whereas pure iteration may obscure the problem's hierarchical nature. For instance, recursive descent methods often incorporate iterative loops for handling repetitive substructures, like token scanning in parsers, to maintain readability without unbounded recursion depth.[42] A prominent example is depth-first search (DFS), which recursively traverses graphs by exploring as far as possible along each branch before backtracking, effectively using the call stack to manage the traversal order. In this implementation, recursion provides an intuitive way to simulate the explicit stack required for DFS, processing vertices and edges in a depth-preferring manner. The standard pseudocode from Cormen et al. outlines DFS as follows:DFS(G)

1 for each vertex u ∈ G.V

2 u.color ← WHITE

3 u.π ← NIL

4 time ← 0

5 for each vertex u ∈ G.V

6 if u.color == WHITE

7 DFS-VISIT(G, u)

DFS-VISIT(G, u)

8 u.color ← GRAY

9 u.d ← ++time

10 for each v ∈ G.Adj[u]

11 if v.color == WHITE

12 v.π ← u

13 DFS-VISIT(G, v)

14 // Additional processing for other edge types

15 u.color ← BLACK

16 u.f ← ++time

DFS(G)

1 for each vertex u ∈ G.V

2 u.color ← WHITE

3 u.π ← NIL

4 time ← 0

5 for each vertex u ∈ G.V

6 if u.color == WHITE

7 DFS-VISIT(G, u)

DFS-VISIT(G, u)

8 u.color ← GRAY

9 u.d ← ++time

10 for each v ∈ G.Adj[u]

11 if v.color == WHITE

12 v.π ← u

13 DFS-VISIT(G, v)

14 // Additional processing for other edge types

15 u.color ← BLACK

16 u.f ← ++time

IDDFS(root, goal)

1 depth ← 0

2 while true

3 result ← DepthLimitedSearch(root, goal, depth)

4 if result ≠ cutoff

5 return result

6 depth ← depth + 1

DepthLimitedSearch(node, goal, limit)

7 if goal(node)

8 return solution(node)

9 if limit = 0

10 return cutoff

11 cutoff_occurred ← false

12 for each successor in expand(node)

13 result ← DepthLimitedSearch(successor, goal, limit - 1)

14 if result = cutoff

15 cutoff_occurred ← true

16 else if result ≠ failure

17 return result

18 if cutoff_occurred

19 return cutoff

20 else

21 return failure

IDDFS(root, goal)

1 depth ← 0

2 while true

3 result ← DepthLimitedSearch(root, goal, depth)

4 if result ≠ cutoff

5 return result

6 depth ← depth + 1

DepthLimitedSearch(node, goal, limit)

7 if goal(node)

8 return solution(node)

9 if limit = 0

10 return cutoff

11 cutoff_occurred ← false

12 for each successor in expand(node)

13 result ← DepthLimitedSearch(successor, goal, limit - 1)

14 if result = cutoff