Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reserve currency

View on Wikipedia

A reserve currency is a foreign currency that is held by governments, central banks or other monetary authorities as part of their foreign exchange reserves.[1] The reserve currency can be used in international transactions, international investments and all aspects of the global economy. It is often considered a hard currency or safe-haven currency.

The United Kingdom's pound sterling was the primary reserve currency of much of the world in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.[2] However, by the middle of the 20th century, the United States dollar had become the world's dominant reserve currency.[3]

History

[edit]Reserve currencies have come and gone with the evolution of the world's geopolitical order. International currencies in the past have (in addition to those discussed below) included the Greek drachma, coined in the fifth century BC, the Roman denarius, the Byzantine solidus, the Islamic dinar of the Middle Ages, and the French franc.

The Venetian ducat and the Florentine florin was the gold-based currency of choice between Europe and the Arab world from the 13th to the 16th centuries, since gold was easier than silver to mint in standard sizes and transport over long distances. It was the Spanish silver dollar, however, which created the first true global reserve currency recognized in Europe, Asia and the Americas from the 16th to the 19th centuries due to abundant silver supplies from Spanish America.[4]

While the Dutch guilder was a reserve currency of somewhat lesser scope, used between Europe and the territories of the Dutch colonial empire from the 17th to 18th centuries, it was also a silver standard currency fed with the output of Spanish-American mines flowing through the Spanish Netherlands. The Dutch, through the Bank of Amsterdam, were the first to establish a reserve currency whose monetary unit was stabilized using practices familiar to modern central banking (as opposed to the Spanish dollar stabilized through American mine output and Spanish fiat) and which can be considered as a precursor to modern-day monetary policy.[5][6]

The Bank of England was established in 1694, and the Bank of France in the 18th century. The British pound sterling, in particular, was poised to dislodge the Spanish dollar's hegemony as the rest of the world transitioned to the gold standard in the last quarter of the 19th century. At that point, the United Kingdom was the primary exporter of manufactured goods and services, and over 60% of world trade was invoiced in pounds sterling. British banks were also expanding overseas; London was the world centre for insurance and commodity markets and British capital was the leading source of foreign investment around the world; sterling soon became the standard currency used for international commercial transactions.[7] On continental Europe, the bimetallic standard of the French franc remained the unifying currency of several European countries and their colonies under the Latin Monetary Union, which was established in 1865. Peru, Colombia and Venezuela also adopted the system in the 1860s and 1870s.[8]

-

Florentine florin, 1347

-

Spanish piece of eight of Philip V, 1739

-

Silver ducaton worth 3-3.15 Dutch guilders, 1793

-

Sovereign (£1 coin) of Queen Victoria, 1842

-

US double eagle ($20 gold coin), 1907

Attempts were made in the interwar period to restore the gold standard. The British Gold Standard Act reintroduced the gold bullion standard in 1925,[9] followed by many other countries. This led to relative stability, followed by deflation, but because of the onset of the Great Depression and other factors, global trade greatly declined and the gold standard fell. Speculative attacks on the pound forced Britain entirely off the gold standard in 1931.[10][11]

After World War II, the international financial system was governed by a formal agreement, the Bretton Woods system. Under this system, the United States dollar (USD) was placed deliberately as the anchor of the system, with the US government guaranteeing other central banks that they could sell their US dollar reserves at a fixed rate for gold.[12]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the system suffered setbacks ostensibly due to problems pointed out by the Triffin dilemma—the conflict of economic interests that arises between short-term domestic objectives and long-term international objectives when a national currency also serves as a world reserve currency.[13]

Additionally, in 1971 President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the USD to gold, thus creating a fully fiat global reserve currency system. However, gold has persisted as a significant reserve asset since the collapse of the classical gold standard.[14]

Following the 2020 economic recession, the IMF opined about the emergence of "A New Bretton Woods Moment" which could imply the need for a new global reserve currency system.[15]

Global currency reserves

[edit]The IMF publishes the aggregated Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) each quarter.[16] In 2022, IMF researchers reported that while the dollar remains dominant, its share has declined over two decades as central banks diversified into “nontraditional” reserve currencies such as the Australian and Canadian dollars, the Swedish krona, and the South Korean won.[17] The reserves of the individual reporting countries and institutions are confidential.[18] Thus the following table is a limited view about the global currency reserves that only deals with allocated (i.e. reported) reserves:[needs update]

| 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1995 | 1990 | 1985 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1965 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US dollar | 57.80% | 58.42% | 58.52% | 58.80% | 58.92% | 60.75% | 61.76% | 62.73% | 65.36% | 65.73% | 65.14% | 61.24% | 61.47% | 62.59% | 62.14% | 62.05% | 63.77% | 63.87% | 65.04% | 66.51% | 65.51% | 65.45% | 66.50% | 71.51% | 71.13% | 58.96% | 47.14% | 56.66% | 57.88% | 84.61% | 84.85% | 72.93% |

| Euro (until 1999—ECU) | 19.83% | 19.95% | 20.37% | 20.59% | 21.29% | 20.59% | 20.67% | 20.17% | 19.14% | 19.14% | 21.20% | 24.20% | 24.05% | 24.40% | 25.71% | 27.66% | 26.21% | 26.14% | 24.99% | 23.89% | 24.68% | 25.03% | 23.65% | 19.18% | 18.29% | 8.53% | 11.64% | 14.00% | 17.46% | |||

| Japanese yen | 5.82% | 5.69% | 5.54% | 5.52% | 6.03% | 5.87% | 5.19% | 4.90% | 3.95% | 3.75% | 3.54% | 3.82% | 4.09% | 3.61% | 3.66% | 2.90% | 3.47% | 3.18% | 3.46% | 3.96% | 4.28% | 4.42% | 4.94% | 5.04% | 6.06% | 6.77% | 9.40% | 8.69% | 3.93% | 0.61% | ||

| Pound sterling | 4.73% | 4.86% | 4.90% | 4.81% | 4.73% | 4.64% | 4.43% | 4.54% | 4.35% | 4.71% | 3.70% | 3.98% | 4.04% | 3.83% | 3.94% | 4.25% | 4.22% | 4.82% | 4.52% | 3.75% | 3.49% | 2.86% | 2.92% | 2.70% | 2.75% | 2.11% | 2.39% | 2.03% | 2.40% | 3.42% | 11.36% | 25.76% |

| Canadian dollar | 2.77% | 2.59% | 2.39% | 2.38% | 2.08% | 1.86% | 1.84% | 2.03% | 1.94% | 1.77% | 1.75% | 1.83% | 1.42% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese renminbi | 2.18% | 2.29% | 2.61% | 2.80% | 2.29% | 1.94% | 1.89% | 1.23% | 1.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian dollar | 2.06% | 2.14% | 1.97% | 1.84% | 1.83% | 1.70% | 1.63% | 1.80% | 1.69% | 1.77% | 1.59% | 1.82% | 1.46% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Swiss franc | 0.17% | 0.19% | 0.23% | 0.17% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.14% | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.27% | 0.24% | 0.27% | 0.21% | 0.08% | 0.13% | 0.12% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.17% | 0.23% | 0.41% | 0.25% | 0.27% | 0.33% | 0.84% | 1.40% | 2.25% | 1.34% | 0.61% | |

| Deutsche Mark | 15.75% | 19.83% | 13.74% | 12.92% | 6.62% | 1.94% | 0.17% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| French franc | 2.35% | 2.71% | 0.58% | 0.97% | 1.16% | 0.73% | 1.11% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dutch guilder | 0.32% | 1.15% | 0.78% | 0.89% | 0.66% | 0.08% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other currencies | 4.64% | 3.87% | 3.48% | 3.09% | 2.65% | 2.51% | 2.45% | 2.43% | 2.33% | 2.86% | 2.83% | 2.84% | 3.26% | 5.49% | 4.43% | 3.04% | 2.20% | 1.83% | 1.81% | 1.74% | 1.87% | 2.01% | 1.58% | 1.31% | 1.49% | 4.87% | 4.89% | 2.13% | 1.29% | 1.58% | 0.43% | 0.03% |

| Source: World Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves. International Monetary Fund. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The percental composition of currencies of official foreign exchange reserves from 1995 to 2024.[19][20][21]

Theory

[edit]Economists debate whether a single reserve currency will always dominate the global economy.[22] Many have recently argued that one currency will almost always dominate due to network externalities (sometimes called "the network effect"), especially in the field of invoicing trade and denominating foreign debt securities, meaning that there are strong incentives to conform to the choice that dominates the marketplace. The argument is that, in the absence of sufficiently large shocks, a currency that dominates the marketplace will not lose much ground to challengers.

However, some economists, such as Barry Eichengreen, argue that this is not as true when it comes to the denomination of official reserves because the network externalities are not strong.[citation needed] As long as the currency's market is sufficiently liquid, the benefits of reserve diversification are strong, as it insures against large capital losses. The implication is that the world may well soon begin to move away from a financial system dominated uniquely by the US dollar. In the first half of the 20th century, multiple currencies did share the status as primary reserve currencies. Although the British Sterling was the largest currency, both the French franc and the German mark shared large portions of the market until the First World War, after which the mark was replaced by the dollar. Since the Second World War, the dollar has dominated official reserves, but this is likely a reflection of the unusual domination of the American economy during this period, as well as official discouragement of reserve status from the potential rivals, Germany and Japan.

The top reserve currency is generally selected by the banking community for the strength and stability of the economy in which it is used. Thus, as a currency becomes less stable, or its economy becomes less dominant, bankers may over time abandon it for a currency issued by a larger or more stable economy. This can take a relatively long time, as recognition is important in determining a reserve currency. For example, it took many years after the United States overtook the United Kingdom as the world's largest economy before the dollar overtook the pound sterling as the dominant global reserve currency.[2] In 1944, when the US dollar was chosen as the world reference currency at Bretton Woods, it was only the second currency in global reserves.[2]

The G8 also frequently issued public statements as to exchange rates. In the past due to the Plaza Accord, its predecessor bodies could directly manipulate rates to reverse large trade deficits.

Major reserve currencies

[edit]

United States dollar

[edit]The United States dollar is the most widely held currency in the allocated reserves. As of the fourth quarter of 2022, the USD accounted for 58.36% of official foreign exchange reserves.[23][24][needs update] This makes it somewhat easier for the United States to run higher trade deficits with greatly postponed economic ramifications or even postponing a currency crisis. Central bank US dollar reserves, however, are small compared to private holdings of such debt. If non-United States holders of dollar-denominated assets shifted holdings to assets denominated in other currencies, there could be serious consequences for the US economy. The decline of the pound sterling took place gradually over time, and the markets involved adjusted accordingly.[2] However, the US dollar remains the preferred reserve currency because of its stability due to scale and liquidity.[25]

The US dollar's position in global reserves is often questioned because of the growing share of unallocated reserves, and because of the doubt regarding dollar stability in the long term.[26][27] However, the dollar's share in the world's foreign-exchange trades rose slightly from 85% in 2010 to 87% in 2013.[28][better source needed][needs update]

The dollar's role as the largest reserve currency allows the United States to impose unilateral sanctions against actions performed between other countries, for example the American fine against BNP Paribas for violations of U.S. sanctions that were not laws of France or the other countries involved in the transactions.[29] In 2014, China and Russia signed a 150 billion yuan central bank liquidity swap line agreement to get around European and American sanctions on their behaviors.[30]

In 2025, after the implementation of tariffs in the second Trump administration, financial institutions began to rethink the role of US Dollar as reserve currency.[31][32][33]

Euro

[edit]The euro is currently the second most commonly held reserve currency, representing about 20% of international foreign currency reserves. After World War II and the rebuilding of the German economy, the German mark gained the status of the second most important reserve currency after the US dollar. When the euro was introduced on 1 January 1999, replacing the mark, French franc and ten other European currencies, it inherited the status of a major reserve currency from the mark. Since then, its contribution to official reserves has risen continually as banks seek to diversify their reserves, and trade in the eurozone continues to expand.[34]

After the euro's share of global official foreign exchange reserves approached 25% as of year-end 2006 (vs 65% for the U.S. dollar; see table above), some experts have predicted that the euro could replace the dollar as the world's primary reserve currency. See Alan Greenspan, 2007;[35] and Frankel, Chinn (2006) who explained how it could happen by 2020.[36][37] However, as of 2022 none of this has come to fruition due to the European debt crisis which engulfed the PIIGS countries from 2009 to 2014. Instead the euro's stability and future existence was put into doubt, and its share of global reserves was cut to 19% by year-end 2015 (vs 66% for the USD). As of year-end 2020 these figures stand at 21% for EUR and 59% for USD.

Pound sterling

[edit]The United Kingdom's pound sterling was the primary reserve currency of much of the world in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.[2] That status ended after the UK almost bankrupted itself fighting World War I[38] and World War II,[39] and its place was taken by the United States dollar.

In the 1950s, 55% of global reserves were still held in sterling; but the share was 10% lower within 20 years.[2][40]

The establishment of the U.S. Federal Reserve System in 1913 and the economic vacuum following the World Wars facilitated the emergence of the United States as an economic superpower.[41]

As of 30 September 2021[update], the pound sterling represented the fourth largest proportion (by USD equivalent value) of foreign currency reserves and 4.78% of those reserves.[42]

Japanese yen

[edit]Japan's yen is part of the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) special drawing rights (SDR) valuation. The SDR currency value is determined daily by the IMF, based on the exchange rates of the currencies making up the basket, as quoted at noon at the London market. The valuation basket is reviewed and adjusted every five years.[43]

The SDR Values and yen conversion for government procurement are used by the Japan External Trade Organization for Japan's official procurement in international trade.[44]

Chinese renminbi

[edit]The Chinese renminbi officially became a supplementary forex reserve asset on 1 October 2016.[45] It represents 10.92% of the IMF's Special Drawing Rights (SDR) currency basket.[46][47] The Chinese renminbi is the third reserve currency after the U.S. dollar and euro within the basket of currencies in the SDR.[46] (As shown in the table above, the renmimbi is the sixth largest component of international currency reserves.)

Canadian dollar

[edit]A number of central banks (and commercial banks) keep Canadian dollars as a reserve currency. In the economy of the Americas, the Canadian dollar plays a similar role to that played by the Australian dollar (AUD) in the Asia-Pacific region. The Canadian dollar (as a regional reserve currency for banking) has been an important part of the British, French and Dutch Caribbean states' economies and finance systems since the 1950s.[48] The Canadian dollar is also held by many central banks in Central America and South America. It is held in Latin America because of remittances and international trade in the region.[48]

Because Canada's primary foreign-trade relationship is with the United States, Canadian consumers, economists, and many businesses primarily define and value the Canadian dollar in terms of the United States dollar. Thus, by observing how the Canadian dollar floats in terms of the US dollar, foreign-exchange economists can indirectly observe internal behaviours and patterns in the US economy that could not be seen by direct observation. Also, because it is considered a petrodollar, the Canadian dollar has only fully evolved into a global reserve currency since the 1970s, when it was floated against all other world currencies.

The Canadian dollar, from 2013 to 2017, was ranked fifth among foreign currency reserves in the world, overtaking the Australian dollar, but is then being[clarification needed] overtaken by the Chinese Yuan.[49]

Swiss franc

[edit]The Swiss franc, despite gaining ground among the world's foreign-currency reserves[50] and often being used in denominating foreign loans,[51] cannot be considered as a world reserve currency, since the share of all foreign exchange reserves held in Swiss francs has historically been well below 0.5%. The daily trading market turnover of the franc, however, ranked fifth, or about 3.4%, among all currencies in a 2007 survey[needs update] by the Bank for International Settlements.[52]

Calls for an alternative reserve currency

[edit]John Maynard Keynes proposed the bancor, a supranational currency to be used as unit of account in international trade, as reserve currency under the Bretton Woods Conference of 1945. The bancor was rejected in favor of the U.S. dollar.

A report released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in 2010, called for abandoning the U.S. dollar as the single major reserve currency. The report states that the new reserve system should not be based on a single currency or even multiple national currencies but instead permit the emission of international liquidity to create a more stable global financial system.[53][54][55][56]

Countries such as Russia and China, central banks, and economic analysts and groups, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council, have expressed a desire to see an independent new currency replace the dollar as the reserve currency. However, it is recognized that the US dollar remains the strongest reserve currency.[57]

On 10 July 2009, Russian President Medvedev proposed a new 'World currency' at the G8 meeting in London as an alternative reserve currency to replace the dollar.[58]

At the beginning of the 21st century, gold and crude oil were still priced in dollars, which helps export inflation and has brought complaints about OPEC's policies of managing oil quotas to maintain dollar price stability.[59]

Due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and international sanctions, Russia has used the United Arab Emirates dirham as a neutral currency when selling oil to India.[60][61]

Special drawing rights

[edit]Some have proposed the use of the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) special drawing rights (SDRs) as a reserve. The value of SDRs are calculated from a basket determined by the IMF of key international currencies, which as of 2016 consisted of the United States dollar, Euro, Japanese yen, Pound sterling and PRC Renminbi.

Ahead of a G20 summit in 2009, China distributed a paper that proposed using SDRs for clearing international payments and eventually as a reserve currency to replace the U.S. dollar.[62]

On 3 September 2009, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) issued a report calling for a new reserve currency based on the SDR, managed by a new global reserve bank.[63] The IMF released a report in February 2011, stating that using SDRs "could help stabilize the global financial system."[64] The SDR itself is only a minuscule fraction of global currency reserves.[65]

Cryptocurrencies

[edit]According to some cryptocurrency proponents, digital cryptocurrencies could potentially replace fiat currencies as a possible global reserve currency.[66]

See also

[edit]- Commodity currency – Currency moving with commodity prices

- Cryptocurrency – Digital currency not reliant on a central authority

- Exorbitant privilege – Economic gain by reserve currency nation

- Fiat money – Currency not backed by any commodity

- Floating exchange rate – Currency value as determined by foreign market events

- Foreign exchange reserves – Money held by a central bank to pay debts, if needed

- Hard currency – Reliable and stable globally-traded currency

- Krugerrand – South African gold coin

- Seigniorage – Profit from minting money

- Special drawing rights – Supplementary foreign exchange reserve assets defined and maintained by the IMF

- Triffin dilemma – Conflict of economic interests in countries with global reserve currencies

- Impossible trinity – Trilemma in international economics

References

[edit]- ^ "Glossary:Reserve currency". European Commission. Retrieved 2 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Retirement of Sterling as a Reserve Currency after 1945: Lessons for the US Dollar?", Catherine R. Schenk, Canadian Network for Economic History conference, October 2009.

- ^ "The Federal Reserve in the International Sphere", The Federal Reserve System: Purposes & Functions, a publication of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 9th Edition, June 2005

- ^ "'The Silver Way' Explains How the Old Mexican Dollar Changed the World". 30 April 2017.

- ^ Quinn, Stephen; Roberds, William (2005). "The Big Problem of Large Bills: The Bank of Amsterdam and the Origins of Central Banking" (PDF). United States of America: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2005-16.

- ^ Pisani-Ferry, Jean; Posen, Adam S. (2009). The Euro at Ten: The Next Global Currency. United States of America: Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economies & Brueggel. ISBN 978-0-88132-558-4.

- ^ "A history of sterling" by Kit Dawnay, The Telegraph, 8 October 2001

- ^ Willis, Henry Parker (1901). A History of the Latin Monetary Union: A Study in International Monetary Action. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 84.

- ^ Text of the Gold Standard Bill speech Archived 2 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Winston Churchill, House of Commons, 4 May 1925

- ^ Text of speech by Chancellor of the Exchequer Archived 2 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Philip Snowden to the House of Commons, 21 September 1931

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry J. (15 September 2008). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System. Princeton University Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-691-13937-1. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ An Historical Perspective on the Reserve Currency Status of the U.S. Dollar treasury.gov

- ^ Glawson, Joshua D. (9 April 2025). "Watch: Gold's Historic Race to Reclaim Role as Preeminent Reserve Currency". Money Metals Exchange.

- ^ Jabko, Nicolas; Schmidt, Sebastian (2022). "The Long Twilight of Gold: How a Pivotal Practice Persisted in the Assemblage of Money". International Organization. 76 (3): 625–655. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000461. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 245413975.

- ^ Georgieva, Kristalina; Washington, IMF Managing Director; DC. "A New Bretton Woods Moment". IMF. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "IMF Releases Data on the Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves Including Holdings in Renminbi". Imf.org. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Dollar Dominance and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies". IMF. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

- ^ "IMF Data - Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserve - At a Glance". Data.imf.org (in German). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ For 1995–99, 2006–24: "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)". Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- ^ For 1999–2005: International Relations Committee Task Force on Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (February 2006), The Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (PDF), Occasional Paper Series, Nr. 43, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, ISSN 1607-1484ISSN 1725-6534 (online).

- ^ Review of the International Role of the Euro (PDF), Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, December 2005, ISSN 1725-2210ISSN 1725-6593 (online).

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry (May 2005). Sterling's Past, Dollar's Future: Historical Perspectives on Reserve Currency Competition (Report). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). SSRN 723305.

- ^ Chen, Penny (April 2023). "Calls to move away from the U.S. dollar are growing — but the greenback is still king". CNBC.

- ^ "Currency composition of International Foreign Reserves". IMF.

- ^ "In a world of ugly currencies, the dollar is sitting pretty". The Economist. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Why the Dollar's Reign Is Near an End

- ^ "U.N. sees risk of crisis of confidence in dollar", Reuters, 25 May 2011

- ^ "The Dollar and Its Rivals" by Jeffrey Frankel, Project Syndicate, 21 November 2013

- ^ Irwin, Neil (1 July 2014). "In BNP Paribas Case, an Example of How Mighty the Dollar Is". www.nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Smochenko, Anna (13 October 2014). "China, Russia seek 'international justice', agree currency swap line". Agence France-Presse – via Yahoo.

- ^ Partington, Richard (11 April 2025). "The damage is done: Trump's tariffs put the dollar's safe haven status in jeopardy". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ Wee, Rae (11 April 2025). "Mighty U.S. dollar feels heat as Trump's tariffs spark trade turmoil". Reuters. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ Stepek, John (11 April 2025). "Are the US Dollar's Days of Dominance Numbered?". Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ Lim, Ewe-Ghee (June 2006). "The Euro's Challenge to the Dollar: Different Views from Economists and Evidence from COFER (Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves) and Other Data" (PDF). IMF.

- ^ "Euro could replace dollar as top currency-Greenspan", Reuters, 7 September 2007

- ^ Menzie, Chinn; Jeffery Frankel (January 2006). "Will the Euro Eventually Surpass The Dollar As Leading International Reserve Currency?" (PDF). NBER. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- ^ "Aristovnik, Aleksander & Čeč, Tanja, 2010. "Compositional Analysis Of Foreign Currency Reserves In The 1999-2007 Period. The Euro Vs. The Dollar As Leading Reserve Currency," Journal for Economic Forecasting, Vol. 13(1), pages 165-181" (PDF). Institute for Economic Forecasting. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Crafts, Nicolas (27 August 2014). "Walking wounded: The British economy in the aftermath of World War I". VoxEU. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Chickering, Roger (January 2013). A World at Total War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-05238-2. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "The United Nations Charter and Extra-State Warfare: The U.N. Grows Up". The World Financial Review. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ "Born of a Panic: Forming the Fed System - The Region - Publications & Papers - The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis". Minneapolisfed.org. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves". International Monetary Fund. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "SDR Valuation", International Monetary Fund website: "The currency value of the SDR is determined by summing the values in U.S. dollars, based on market exchange rates, of a basket of major currencies (the U.S. dollar, Euro, Japanese yen, and pound sterling). The SDR currency value is calculated daily (except on IMF holidays or whenever the IMF is closed for business) and the valuation basket is reviewed and adjusted every five years."

- ^ Japanese Government Procurement, Japan External Trade Organization website (accessed: 6 January 2015)

- ^ "Going global: Trends and implications in the internationalisation of China's currency". KPMG. 11 January 2017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Special Drawing Right (SDR)".

- ^ "IMF Approves Reserve-Currency Status for China's Yuan". Bloomberg.com. 30 November 2015 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- ^ a b "The Canadian Dollar as a Reserve Currency" by Lukasz Pomorski, Francisco Rivadeneyra and Eric Wolfe, Funds Management and Banking Department, The Bank of Canada Review, Spring 2014

- ^ "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Is the Dollar Dying? Why US Currency Is in Danger" by Jeff Cox, CNBC, 14 February 2013

- ^ "A new global reserve?", The Economist, 2 July 2010

- ^ "Triennial Central Bank Survey, Foreign exchange and derivatives market activity in 2007" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. December 2007.

- ^ "Scrap dollar as sole reserve currency: U.N. Report". Reuters.com. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "UN report calls for new global reserve currency to replace U.S. dollar". People's Daily, PRC. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ Conway, Edmund (7 September 2009). "UN wants new global currency to replace dollar". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "World Economic and Social Survey 2010". U?N.org. 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Will the Gulf currency peg survive?". Quorum Centre for Strategic Studies. 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Medvedev Shows Off Sample Coin of New 'World Currency' at G-8". Reuters.com. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ Burleigh, Marc. "OPEC leaves oil quotas unchanged, seeing economic 'risks'." AFP, 11 December 2010.

- ^ Verma, Nidhi; Verma, Nidhi (3 February 2023). "Indian refiners pay traders in dirhams for Russian oil". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023.

- ^ "Indian imports of Russian oil drop to lowest in a year".

- ^ "China backs talks on dollar as reserve -Russian source, Reuters, 19 March 2, 2009". Reuters.com. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2009". Unctad.org. 6 October 2002. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Rooney, Ben (10 February 2011). "IMF calls for dollar alternative". CNN Money.

- ^ Kennedy, Scott (20 August 2015). "Let China Join the Global Monetary Elite". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Mattackal, Lisa Pauline; Singh, Medha (12 April 2022). "Cryptoverse: 10 billion reasons bitcoin could become a reserve currency". Reuters. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Prasad, Eswar S. (2014). The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2011). Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975378-9.

- Rogoff, Kenneth S. (2025). Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider's View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-27531-5.

- Varoufakis, Yanis (2011). The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the Global Economy. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-78360-610-8.

- Arslanalp, Serkan; Eichengreen, Barry J.; Simpson‑Bell, Chima (2022). "The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance: Active Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies". Journal of International Economics. 138 103656. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2022.103656.

Reserve currency

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Definition and Functions

A reserve currency is a foreign currency held in significant quantities by central banks and monetary authorities as part of their official foreign exchange reserves, enabling them to meet balance of payments needs, intervene in currency markets, and maintain economic stability.[2] These reserves consist primarily of highly liquid assets denominated in the reserve currency, such as government securities, deposits, and gold, which allow countries to address short-term liquidity shortages without disrupting domestic markets.[8] The designation arises from the currency's widespread acceptance in global trade, investment, and finance, reducing transaction costs and exchange rate risks for users.[5] The primary functions of a reserve currency include serving as a medium for international payments and settlements, where it facilitates cross-border trade by minimizing the need for multiple currency conversions; for instance, as of 2024, over 80% of global trade invoices are denominated in the dominant reserve currency, the U.S. dollar.[3] Central banks utilize these holdings to intervene in foreign exchange markets, buying or selling the reserve currency to influence their domestic exchange rate and counteract volatility, as evidenced by interventions during the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis.[5] Additionally, reserve currencies act as a store of value, preserving purchasing power over time due to the issuing country's economic stability and deep financial markets, allowing reserves to hedge against inflation or domestic currency depreciation.[14] Another key role is providing liquidity during external shocks, enabling governments to repay foreign debts or import essentials without immediate liquidation of illiquid assets; empirical data from IMF Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) shows that reserve currencies comprised about 90% of allocated global reserves in Q1 2025, underscoring their buffer function.[8] Reserve status also confers seigniorage benefits to the issuing nation, as foreign demand for its currency allows low-cost borrowing through Treasury securities, with U.S. external debt held abroad exceeding $8 trillion in mid-2025.[4] These functions collectively enhance the reserve currency's network effects, where its dominance perpetuates further adoption due to liquidity and reduced risk premiums in transactions.[6]Essential Criteria for Reserve Status

A currency attains reserve status when it is widely held by central banks and monetary authorities for purposes such as transaction facilitation, liquidity management, and hedging against domestic economic shocks, requiring attributes that ensure long-term value preservation and ease of use. Essential criteria include the issuing economy's scale and integration into global trade, as larger economies generate greater demand for their currency in cross-border settlements. For example, currencies like the US dollar benefit from the United States' approximately 15-25% share of global GDP and merchandise exports, fostering habitual use in invoicing and reserves.[12][15] Institutional credibility forms another core pillar, encompassing sound monetary policy, fiscal discipline, and transparent governance that minimize default risk and inflation volatility. Issuers must demonstrate consistent policy frameworks, such as independent central banks committed to price stability, to build investor trust; the US Federal Reserve's mandate for dual objectives of price stability and maximum employment has underpinned dollar holdings since 1913, despite periodic deficits.[16][15] Political stability and rule of law further reinforce this by safeguarding property rights and contract enforcement, deterring capital flight; historical shifts, like the British pound's decline post-World War II, illustrate how geopolitical disruptions erode reserve appeal absent robust legal foundations.[15] Financial market depth and liquidity are indispensable, enabling the issuance of high volumes of safe, marketable assets like government bonds that serve as collateral in global finance. Deep markets allow reserves to be parked productively with minimal transaction costs or price impact; the US Treasury market, with over $27 trillion in outstanding debt as of 2023, exemplifies this, far exceeding alternatives like eurozone bonds which constitute less than 50% of GDP in safe assets.[15] Full convertibility and minimal capital controls ensure usability, while network effects—arising from widespread adoption—amplify these traits, though they depend on initial fulfillment of fundamentals rather than vice versa.[17] Currencies failing these, such as the Chinese renminbi with its capital restrictions, have seen limited reserve uptake despite economic size, holding only about 2.5% of global reserves as of 2023.[16]Historical Development

Pre-Modern and Classical Periods

In classical antiquity, coinage emerged as a medium facilitating trade across regions, with certain issues gaining prominence due to their standardized weight, purity, and the issuing polity's economic influence. The Athenian tetradrachm, featuring an owl emblem and minted from high-purity silver sourced from the Laurion mines, circulated widely throughout the Mediterranean from the 5th century BCE, serving as a de facto standard for international commerce owing to Athens' naval dominance and reliable minting practices.[18] [19] These coins, weighing approximately 17 grams at 95% fineness, were accepted from the Black Sea to Sicily, functioning analogously to reserves by enabling cross-border payments and hoarding as stores of value.[20] The Roman denarius, introduced around 211 BCE as a silver coin of about 4 grams initially at near-pure fineness, became the empire's principal currency and extended its utility in trade networks spanning Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Its widespread acceptance stemmed from Rome's centralized authority and military enforcement of economic standards, allowing it to underpin transactions from provincial markets to frontier exchanges, though progressive debasement from the 1st century CE eroded its reliability over time.[21] [22] During the early medieval period, the Byzantine gold solidus, first struck by Emperor Constantine I in 312 CE at 4.5 grams of pure gold, maintained exceptional stability for over seven centuries, underpinning international trade centered on Constantinople. Known as the nomisma in Byzantium and bezant in the West, it circulated across Eurasia and Africa, prized for its unchanging weight and fineness until debasements in the 11th century, thus acting as a benchmark for merchants and treasuries alike. [23] In late medieval Europe, Italian city-states filled the vacuum left by Byzantine decline with high-quality gold coins that dominated Eurasian trade. The Florentine florin, inaugurated in 1252 with 3.5 grams of fine gold and a lily-fleur-de-lis design, achieved ubiquity due to Florence's banking prowess and the coin's consistent purity, serving as a unit of account and reserve asset from England to the Levant until the 16th century.[24] Similarly, the Venetian ducat, minted from 1284 onward with identical gold content and a Christ-in-mandorla motif, leveraged Venice's maritime empire to become a staple in Mediterranean and overland commerce, retaining prestige into the early modern era.[25] [26]Gold Standard Era (19th-early 20th Century)

The classical gold standard emerged in the late 19th century, with major economies adopting fixed convertibility of their currencies into gold at par values, enabling predictable exchange rates and supporting expansive global trade volumes that grew from $1.9 billion in 1850 to $19.7 billion by 1913 in constant dollars.[27] This system relied on gold reserves to back domestic money supplies, but international settlements often utilized key currencies like the British pound sterling, which served as the dominant reserve asset due to London's role as the world's financial hub and Britain's command of over 25% of global industrial output by 1880.[28] The pound's reserve status stemmed from its full convertibility into gold at £3 17s 10½d per ounce since 1717, reinforced by Britain's naval supremacy and vast colonial trade networks that funneled sterling-denominated bills of exchange for commodities like cotton and tea.[29] Britain formalized the gold standard in 1821 following the resumption of specie payments after the Napoleonic Wars, becoming the first major power to do so and setting a model emulated by others.[29] Germany adopted it in 1871 after unifying and demonetizing silver from its prior bimetallic system, while the United States effectively joined in 1879 upon Treasury gold reserves exceeding the greenback liability under the Resumption Act of 1875.[30] France aligned in 1878 via the Latin Monetary Union, and by 1900, over 50 countries, including Japan in 1897 and Russia in 1897 (though with interruptions), had adopted gold convertibility, covering roughly 80% of world trade.[31] Central banks and governments held reserves primarily in gold bars or coin, but foreign exchange reserves increasingly comprised sterling balances, which by 1900 constituted about 62% of allocated global reserves, far outpacing the U.S. dollar at 0%.[32] This era featured low inflation averaging under 1% annually across gold-standard countries from 1870 to 1914, attributed to gold's supply constraints balancing monetary expansion with mining discoveries like South Africa's Witwatersrand output surging from 0.3 million ounces in 1886 to 7.5 million by 1898.[28] The pound facilitated efficient clearing through the London bill market, where acceptance houses discounted short-term trade credits, reducing the need for physical gold shipments and leveraging network effects from sterling's liquidity in 60% of global merchant shipping by 1913.[30] Yet, adherence required fiscal discipline, as balance-of-payments deficits triggered automatic outflows of gold reserves, enforcing adjustments via higher interest rates or deflation, a mechanism that maintained parity but amplified recessions, as seen in Britain's 1890 Baring Crisis.[27] The system's stability unraveled with World War I in 1914, when Britain and most adherents suspended convertibility to finance deficits through inflationary note issuance, with the Bank of England's gold exports banned and the pound temporarily floating off gold until partial restoration in 1925 at prewar parity.[29] This interwar revival proved fragile, collapsing amid the Great Depression by 1931 for Britain, highlighting vulnerabilities to political pressures overriding metallic discipline.[33]Bretton Woods System (1944-1971)

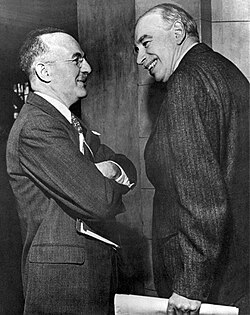

The Bretton Woods Conference, convened from July 1 to 22, 1944, in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, brought together delegates from 44 Allied nations to design a postwar international monetary framework aimed at fostering economic stability and reconstruction after World War II.[34] The agreement established fixed but adjustable exchange rates, with participating currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar at par values within a 1% band, and the dollar itself convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per troy ounce.[35] This structure positioned the U.S. dollar as the system's anchor, leveraging America's vast gold reserves—holding about two-thirds of the world's monetary gold by 1944—and its economic dominance, which accounted for roughly half of global industrial output.[35] The conference also created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to oversee exchange rate parities, provide short-term loans to countries facing balance-of-payments deficits, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, later World Bank) to finance long-term reconstruction projects.[36] ![Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes at Bretton Woods][float-right] Under the system, central banks accumulated U.S. dollars as primary reserves for international transactions and to defend their currency pegs, marking the dollar's ascent as the preeminent global reserve currency.[35] Countries maintained convertibility of their currencies into dollars for current account transactions, while the U.S. committed to redeeming official dollar holdings for gold upon request, though in practice, this gold window was increasingly strained by growing U.S. trade and fiscal deficits in the 1960s.[37] The framework promoted trade liberalization by reducing exchange rate volatility, with IMF lending facilities—drawing on subscribed quotas primarily in dollars—enabling deficit nations to avoid abrupt devaluations that had exacerbated the Great Depression. By 1958, as European and Japanese economies recovered, the system facilitated a surge in global reserves, with dollars comprising over 70% of allocated reserves by the late 1960s, reflecting network effects from the U.S.'s deep financial markets and military presence underpinning dollar confidence.[38] Tensions inherent in the arrangement, later formalized as the Triffin dilemma, emerged as U.S. liquidity provision via deficits flooded the world with dollars exceeding America's gold backing, eroding convertibility credibility.[39] Speculative pressures mounted, exemplified by the 1961 London Gold Pool's failure to stabilize prices and runs on U.S. gold stocks, which fell from 20,000 metric tons in 1949 to about 8,100 tons by 1971.[37] On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon unilaterally suspended dollar-to-gold convertibility in what became known as the "Nixon Shock," imposing a 10% import surcharge and wage-price controls to address inflation and a weakening dollar amid Vietnam War spending and domestic programs.[40] This effectively dismantled the fixed-rate core of Bretton Woods, transitioning the world toward floating exchange rates by 1973, though the dollar retained reserve dominance due to entrenched use in trade invoicing and oil markets.[41] The IMF adapted by amending its Articles of Agreement in 1976 to accommodate flexible rates, but the original gold-dollar peg's collapse highlighted the unsustainable asymmetry of relying on one nation's currency for global liquidity.[39]Post-Bretton Woods and USD Hegemony (1971-Present)

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the United States dollar into gold for foreign governments, an action known as the "Nixon Shock," which dismantled the Bretton Woods system's fixed exchange rate regime and ushered in an era of floating currencies and fiat money.[40][41] This decision addressed mounting U.S. balance-of-payments deficits, inflationary pressures from Vietnam War spending, and foreign demands for gold redemption that depleted U.S. reserves from 574 million ounces in 1945 to about 280 million by 1971.[42][43] Despite predictions of diminished U.S. influence, the dollar's role as the preeminent reserve currency persisted and intensified, supported by the depth of U.S. financial markets, military power, and institutional trust in American governance.[44] In the ensuing years, the U.S. reinforced dollar hegemony through the petrodollar system, originating from agreements in 1973-1974 between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, whereby oil exports by OPEC nations—particularly Saudi Arabia—were denominated and settled exclusively in dollars.[45][46] This arrangement, incentivized by U.S. security guarantees and arms sales, compelled oil-importing countries to accumulate dollars for purchases, while petrodollar surpluses were recycled into U.S. Treasury securities, sustaining demand and low borrowing costs for the U.S.[47] By 1975, Saudi Arabia alone held over $25 billion in dollar-denominated assets, amplifying global liquidity in USD and embedding it in energy trade.[48] The dollar's reserve share remained robust throughout the late 20th century, comprising over 70% of allocated global foreign exchange reserves by the 1990s, bolstered by the Eurodollar market's expansion and the absence of viable alternatives amid the Soviet ruble's inconvertibility and European fragmentation pre-euro.[49] Empirical data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) indicate the USD's share hovered around 65-70% from the 1980s through the early 2000s, reflecting its use in 88% of foreign exchange transactions and as the pricing currency for commodities beyond oil.[5][3] Into the 21st century, USD dominance faced scrutiny amid rising multipolarity, with China's yuan internationalization efforts, BRICS initiatives for local-currency trade, and responses to U.S. sanctions on Russia post-2014 and 2022 prompting some diversification—Russia reduced its dollar reserves from 40% in 2015 to under 10% by 2023.[50][51] However, these shifts have been marginal; as of Q1 2025, the dollar accounted for 58% of global allocated reserves, down modestly from 66% in 2015 but far exceeding the euro's 20% and others' shares under 6% each.[52][11] Adjusted for exchange rate fluctuations, the Q2 2025 share stabilized at approximately 58%, underscoring resilience driven by the dollar's liquidity premium and the U.S. economy's 25% share of global GDP.[53][54] U.S. financial sanctions, wielded via dollar-clearing systems like SWIFT, have paradoxically reinforced hegemony by deterring alternatives, as non-compliant actors face exclusion from dollar access, though they accelerate bilateral non-dollar swaps limited to 5-10% of global trade volumes.[55][56] As of 2025, over 90% of forex transactions and 50% of global debt issuance remain dollar-denominated, affirming the "exorbitant privilege" of seigniorage and deficit financing without immediate inflationary backlash.[3][57] Despite geopolitical strains, no rival currency matches the dollar's combination of convertibility, rule of law, and market infrastructure, sustaining its central role absent a systemic U.S. fiscal collapse.[58]Current Composition and Trends

Allocation of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves

The allocation of global foreign exchange reserves is tracked primarily through the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) dataset, which compiles self-reported data from central banks and monetary authorities representing over 90 percent of total global reserves.[59] As of the second quarter of 2025, total official foreign exchange reserves stood at approximately $12.945 trillion, with allocated reserves—those broken down by specific currencies—comprising the majority.[60] The U.S. dollar maintains the largest share, accounting for 56.32 percent of allocated reserves on an unadjusted basis at the end of Q2 2025, down from 57.79 percent in Q1 due largely to a 7.9 percent depreciation of the dollar against the euro during the quarter.[11] When adjusted for these exchange rate effects to reflect changes in underlying holdings, the dollar's share remained relatively stable at around 57.67 percent, indicating minimal shifts in actual reserve managers' preferences.[11] The euro ranked second with an unadjusted share of 21.13 percent in Q2 2025, up from 20.00 percent in Q1, again primarily attributable to valuation changes from the dollar's weakening rather than net purchases or sales.[11] Exchange-rate-adjusted figures show the euro's share edging slightly lower to 19.96 percent, underscoring the distorting impact of currency fluctuations on reported compositions.[11] Remaining allocated reserves are distributed among other currencies, including the Japanese yen (typically 5-6 percent), British pound (around 4-5 percent), and smaller portions in the Chinese renminbi (approximately 2 percent), Canadian dollar, Australian dollar, and Swiss franc, with the balance in miscellaneous currencies.[3] Unallocated reserves, not specified by currency, constitute about 10-15 percent of the total, reflecting non-disclosed holdings that central banks choose not to report in detail.[11] This structure highlights the dollar's enduring primacy, supported by its liquidity and institutional depth, despite gradual diversification efforts by some reserve holders.[3]Recent Shifts and Empirical Data (Up to 2025)

In response to geopolitical events, including the freezing of Russian central bank assets following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, some nations accelerated diversification of foreign exchange reserves away from U.S. dollar-denominated assets to mitigate sanction risks.[61] This prompted increased allocations to gold and, to a lesser extent, non-traditional currencies, though empirical data indicates no abrupt collapse in dollar dominance.[11] The International Monetary Fund's Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) dataset, aggregating self-reported holdings from over 140 countries, reveals that the US dollar accounted for 58.4% of allocated global foreign exchange reserves in Q4 2023, a slight decline from 59.2% in Q3 2023; the dollar's share hovered around 58 percent through 2024, down modestly from 59 percent in 2020 but stabilizing when adjusted for exchange rate fluctuations.[59][3] Central banks' net gold purchases reached record levels from 2022 to 2025, totaling over 1,000 metric tons annually in peak years, driven by emerging market institutions seeking hedges against fiat currency volatility and geopolitical weaponization of reserves.[62] By mid-2025, gold surpassed U.S. Treasuries as the second-largest reserve component after currencies, comprising approximately 18 percent of global reserves—up from 11 percent in 2015—with holdings exceeding 36,000 tons worldwide.[63][64] This shift reflects causal factors like distrust in sanction-vulnerable assets rather than a coordinated de-dollarization, as gold's non-yielding nature limits it to portfolio insurance rather than transactional use.[65] The Chinese renminbi (RMB) saw incremental gains in reserve status, with its share in global payments rising to 3.17 percent by September 2025, ranking fourth behind the dollar, euro, and pound, amid China's bilateral swap lines and trade settlement pushes.[66] However, COFER data pegs RMB's reserve allocation at under 3 percent through 2024, constrained by capital controls and limited convertibility, despite over 80 central banks holding modest positions totaling around $274 billion as of 2022 (with slower subsequent growth).[67][68] Euro holdings edged up to 20.1 percent by end-2024 from 19.8 percent prior, reflecting safe-haven demand, while other currencies like the yen and pound remained stable below 6 percent combined.[69]| Currency | Share of Allocated Reserves (Q4 2020) | Share (End 2024) | Key Driver of Change (2023-2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Dollar | 59.0% | 57.8% | Geopolitical diversification offset by liquidity needs |

| Euro | 20.5% | 20.1% | Marginal safe-haven inflows |

| Renminbi | ~2.0% | ~2.5% | Trade finance expansion in Asia |

| Others (Yen, Pound, etc.) | ~10% | ~10% | Stable |

Theoretical Foundations

Network Effects and Liquidity Premiums

The adoption of a currency as a reserve asset generates network effects, where its marginal utility rises with the scale of its usage across international trade, invoicing, and central bank holdings. As more entities incorporate the currency into their portfolios and transactions, financial markets deepen, transaction costs decline due to standardized pricing and reduced exchange rate risk, and information efficiencies improve, fostering further adoption in a positive feedback loop. This dynamic explains the path dependence observed in the international monetary system, where incumbent currencies maintain dominance despite economic shifts; for instance, econometric analyses of trade invoicing reveal that a currency's share in global payments exhibits increasing returns to scale, with network externalities accounting for up to 20-30% of the variance in adoption patterns across commodities like oil.[73][74] Empirical evidence from BIS Triennial Central Bank Surveys underscores these effects, showing that the U.S. dollar's 88% share in foreign exchange turnover as of 2022 correlates with its entrenched role in cross-border settlement, creating barriers to entry for challengers through coordination failures among users.[75] Similarly, panel data regressions on reserve compositions from 1990-2020 indicate that a 1% increase in a currency's global usage predicts a 0.5-1% rise in subsequent reserve allocations, net of macroeconomic fundamentals like GDP share, highlighting lock-in mechanisms that perpetuate inertia.[76] These network externalities not only amplify the currency's role in unit-of-account functions but also deter diversification, as switching costs—such as repricing contracts or rebuilding liquidity pools—escalate nonlinearly with the system's scale. Complementing network effects, reserve currencies command a liquidity premium, reflecting the high convertibility and depth of their associated markets, which allow holders to execute large transactions with minimal price impact. This premium manifests as lower bid-ask spreads and yield discounts on the issuer's sovereign debt; for the U.S., global demand for Treasury securities has suppressed 10-year yields by an estimated 0.5-1 percentage points relative to fundamentals since the 2000s, enabling cheaper external financing equivalent to 0.2-0.5% of GDP annually in seigniorage-like benefits.[16][77] Models incorporating money demand frictions further quantify this as a wedge where dollar-denominated assets yield lower returns yet attract hoarding during stress, as evidenced by the 2020 "dash for cash" episode when offshore dollar funding rates spiked 200-300 basis points amid shortages.[78] The interplay between network effects and liquidity reinforces dominance: broader adoption begets deeper markets, elevating the premium and entrenching the currency against erosion, though empirical tests suggest diminishing marginal returns beyond critical mass thresholds around 40-50% global share.[73] These liquidity advantages contrast with gold, whose limitations—including poor liquidity for large-scale transactions due to physical handling requirements, absence of interest yield, and high storage costs—prevent it from fully supplanting the USD, which provides efficient, interest-bearing liquidity through deep financial markets and systems like SWIFT, reinforced by network effects and arrangements such as petrodollar recycling.[79]Triffin Dilemma and Inherent Tensions

The Triffin dilemma, named after Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, identifies a core instability in systems where a national currency serves as the primary global reserve asset. Triffin argued in his 1960 testimony to the U.S. Joint Economic Committee that, under the Bretton Woods regime, the United States was compelled to run persistent balance-of-payments deficits to supply the world with sufficient dollar liquidity for trade and reserves.[80] However, these deficits inevitably accumulated foreign-held dollars exceeding the U.S. gold backing, eroding international confidence in the dollar's convertibility at the fixed $35 per ounce rate and risking a speculative run on U.S. gold reserves.[81] This created an inescapable tension: insufficient deficits stifled global growth through liquidity shortages, while excessive deficits undermined the reserve currency's credibility.[82] The dilemma manifested empirically during the 1960s, as U.S. deficits—reaching $1.7 billion in 1958 and escalating amid Vietnam War spending and domestic programs—doubled foreign dollar claims to over $40 billion by 1970, surpassing U.S. gold stocks of $11 billion.[41] Foreign central banks, particularly France under Charles de Gaulle, converted dollars to gold, draining U.S. Fort Knox holdings from 574 million ounces in 1945 to 261 million by August 1971.[41] On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended dollar-gold convertibility in the "Nixon Shock," effectively ending Bretton Woods and validating Triffin's prediction of systemic collapse due to inherent liquidity-confidence trade-offs.[41] Beyond the gold-exchange standard, the Triffin dilemma underscores broader inherent tensions for any reserve currency issuer. A dominant currency demands sound monetary policy to preserve value—low inflation, fiscal restraint, and institutional trust—to sustain foreign holdings, yet global demand requires the issuer to export its currency via current-account deficits, exposing it to external imbalances and policy pressures from abroad.[83] This conflict pits domestic economic priorities, such as full employment or growth stimulus, against international obligations for stability, potentially amplifying boom-bust cycles as the issuer absorbs global savings gluts or faces sudden stops in demand.[81] Post-1971 floating rates mitigated gold runs but perpetuated the paradox, with the U.S. dollar's 59% share of allocated reserves as of 2023 reflecting ongoing deficits that, while providing liquidity, heighten vulnerability to confidence crises if fiscal profligacy erodes perceived solvency.[82] Empirical analyses, including BIS studies, affirm that no national currency can indefinitely reconcile these roles without reforms like supranational assets, though Triffin's proposed composite reserve unit faced political resistance.[80]Benefits to the Issuing Nation (Exorbitant Privilege)

The exorbitant privilege denotes the economic advantages conferred upon a nation issuing the dominant global reserve currency, primarily through the ability to sustain external imbalances and access cheaper financing without immediate disciplinary pressures from international markets. This concept, articulated by French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d'Estaing in 1965, highlights how the issuing country can export its currency in exchange for real goods and services, effectively running persistent trade deficits financed by foreigners' willingness to accumulate its liabilities as reserves.[5] Empirical analyses confirm that reserve currency status correlates with lower sovereign borrowing costs, as foreign official holdings—often comprising a significant share of the issuer's debt—increase demand and suppress yields. For instance, econometric models estimate that the United States benefits from a yield reduction of 10 to 30 basis points on its Treasury securities attributable to the dollar's reserve role, translating to annual interest savings of roughly $30 billion to $90 billion given federal debt levels around $35 trillion as of 2025.[84] [85] A core component is seigniorage, the revenue derived from the difference between the face value of currency issued and its production cost, amplified when foreigners hold non-interest-bearing notes or deposits. For the United States, foreign demand for dollars—estimated at over $2 trillion in physical currency alone held abroad as of recent Federal Reserve data—provides an implicit interest-free loan, as the U.S. government incurs minimal costs to produce these assets while avoiding the need to pay interest that domestic holders might demand. This generates fiscal gains equivalent to the opportunity cost of funds, with historical empirical tests indicating seigniorage from international currency status adding 0.2% to 0.5% of GDP annually for dominant issuers like the dollar in the post-Bretton Woods era.[86] Such benefits extend beyond direct revenue to indirect effects, including reduced rollover risks on short-term debt, as global liquidity preferences favor the reserve currency's instruments.[85] Reserve status further bolsters domestic financial markets by enhancing liquidity and depth, lowering transaction costs for U.S. entities and facilitating easier capital access for corporations and households. This network effect perpetuates the privilege, as incumbency advantages—rooted in historical path dependence and institutional trust—sustain high foreign holdings despite alternatives. However, causal realism underscores that these gains are not costless; they incentivize fiscal profligacy, potentially inflating asset bubbles or eroding long-term competitiveness through chronic deficits, though the immediate benefits manifest as elevated living standards funded by global savers. Quantifications from balance-of-payments data show the U.S. current account deficit averaging 3-6% of GDP since 1980, largely sustainable due to reserve demand absorbing dollar outflows without precipitating currency depreciation or capital flight.[87][88]Dominant Reserve Currencies

United States Dollar

The United States dollar (USD) has served as the world's preeminent reserve currency since the establishment of the Bretton Woods system in 1944, retaining this status even after the system's collapse in 1971 when the USD's convertibility to gold ended.[4] Post-1971, the USD's role expanded due to the depth and liquidity of U.S. financial markets, which facilitated its use in international transactions without the need for fixed exchange rates.[3] As of 2024, the USD comprised approximately 58 percent of disclosed global official foreign exchange reserves, surpassing all other currencies combined and declining only modestly from a peak of 72 percent in 2001.[3] [3] In foreign exchange reserves reported to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) via its Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) dataset, the USD's share stood at 57.7 percent in the first quarter of 2025, with exchange-rate-adjusted figures showing stability around 58 percent through the second quarter despite raw data fluctuations driven by currency valuation effects.[69] [11] This dominance reflects central banks' preferences for USD-denominated assets, such as U.S. Treasury securities, which offer high liquidity and low transaction costs; for instance, foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries exceeded $8 trillion as of mid-2025.[3] The USD also predominates in global payment systems, accounting for about 40 percent of international payments via SWIFT in 2024, far exceeding the euro's 35 percent share.[3] Beyond reserves, the USD's role in trade invoicing underscores its entrenchment, with empirical data indicating it priced 96 percent of trade in the Americas, 74 percent in the Asia-Pacific, and 79 percent in other regions between 1999 and 2019, patterns that persisted into the 2020s due to invoicing inertia and risk hedging.[3] In foreign exchange markets, the USD was involved in nearly 90 percent of global transactions as of 2022, enabling efficient settlement and reducing exchange rate risks for non-U.S. trade partners.[89] This usage stems from causal factors including the scale of U.S. capital markets—totaling over $50 trillion in debt and equity as of 2024—and the perceived stability of U.S. institutions, where rule-of-law indices rank the U.S. among the highest globally, fostering trust in USD assets during crises.[3] [8] Geopolitical elements reinforce this position, as over 70 percent of USD reserve holdings are by countries with formal military alliances or security ties to the U.S., mitigating risks of asset freezes compared to alternatives like the renminbi, which faces capital controls.[90] Despite narratives of de-dollarization, empirical trends show limited erosion; nontraditional currencies' combined reserve share rose to only 3-4 percent by 2024, insufficient to challenge USD liquidity premiums.[8] The USD's "exorbitant privilege" allows the U.S. to finance deficits at lower costs, with foreign demand suppressing U.S. interest rates by an estimated 0.5-1 percentage point annually.[5] However, vulnerabilities persist, including reliance on foreign willingness to hold USD assets amid U.S. fiscal expansion, which reached a $1.8 trillion deficit in fiscal year 2024.[50]Eurozone Euro

The euro, introduced as an accounting currency on January 1, 1999, and in physical form on January 1, 2002, serves as the common currency for 20 European Union member states comprising the Eurozone, representing a combined economy of approximately 340 million people and about 22% of global GDP as of 2024. As the world's second-most held reserve currency after the US dollar, it accounts for roughly 20% of allocated global foreign exchange reserves according to IMF Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) data through the second quarter of 2025. This share has remained relatively stable over the past decade, fluctuating between 19% and 21%, despite initial post-launch optimism that it might challenge dollar dominance more aggressively.[91] The euro's reserve status stems from the Eurozone's deep and liquid financial markets, which facilitate large-scale transactions, and the European Central Bank's (ECB) mandate for price stability, enabling predictable monetary policy independent of national politics.[92] It benefits from network effects inherited from predecessor currencies like the Deutsche Mark, which held about 15% of global reserves pre-euro, and offers issuers seigniorage gains estimated at 0.3-0.5% of Eurozone GDP annually from international demand.[93] Foreign central banks hold euro assets for diversification, with advantages including lower external financing costs for Eurozone governments and firms due to global demand for euro-denominated safe assets like German bunds.[94] However, the currency's international role is constrained by the absence of a unified fiscal authority, leading to asymmetric shocks across member states without automatic stabilizers like federal transfers.[95] The 2010-2012 sovereign debt crisis significantly undermined confidence in the euro as a reserve asset, as peripheral countries like Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain faced spiking yields on government bonds exceeding 7%, prompting ECB interventions such as the Long-Term Refinancing Operations and outright monetary transactions.[96] Reserve managers reduced euro holdings amid fears of fragmentation or exit risks, with the currency's global reserve share dropping from a peak of 28% in 2008 to below 20% by 2015, reflecting perceived vulnerabilities from divergent national fiscal policies and lack of mutualized debt issuance.[97] Post-crisis reforms, including the European Stability Mechanism and Banking Union, mitigated some risks but did not fully resolve underlying tensions, as evidenced by persistent sovereign-bank loops where national debts indirectly burden the ECB balance sheet.[98] In recent years through 2025, the euro has seen modest gains in reserve allocation, rising to 20.1% by end-2024 from 19.8% prior, partly as central banks diversified away from a weakening dollar amid US fiscal deficits and policy uncertainty.[69] Yet, its share in global payments and trade invoicing lags at around 19% and 30% respectively, limited by energy imports predominantly priced in dollars and geopolitical events like Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which highlighted Eurozone energy dependencies without boosting euro internationalization.[91] Proposals to enhance its status, such as expanding euro-denominated safe assets via joint EU debt or capital markets union, face political hurdles from fiscal conservatives in northern member states wary of moral hazard.[99] Empirical evidence suggests the euro functions more as a regional store of value than a seamless global medium, with liquidity premiums inferior to the dollar due to fragmented government bond markets and no single sovereign guarantor.[100]Other Notable Currencies (Yen, Pound, Swiss Franc)

The Japanese yen (JPY) ranks as the third-largest reserve currency by share in official foreign exchange reserves, comprising approximately 5.3% of allocated global reserves as of the first quarter of 2025, according to IMF Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) data. Its role emerged prominently in the post-World War II era, bolstered by Japan's export-driven economic miracle and accumulation of vast current account surpluses, which elevated the yen's international usage in the 1970s and 1980s; by 1991, its reserve share peaked near 9%, reflecting the country's status as the world's second-largest economy at the time.[4] However, prolonged deflationary pressures, banking crises in the 1990s, and the Bank of Japan's zero-interest-rate policies since 1999 have eroded its appeal, leading to a steady decline to current levels, as central banks prioritize higher-yield, more liquid alternatives amid Japan's persistent current account imbalances and frequent yen interventions to curb depreciation—such as multiple rounds in 2022-2024 totaling over $60 billion to support the currency against the U.S. dollar.[101] Despite these challenges, the yen retains safe-haven attributes during global risk-off events due to Japan's net creditor position and low inflation volatility, though its reserve status is constrained by shallow bond market liquidity relative to the dollar or euro and domestic yield curve control policies that suppress returns for foreign holders.[102] The British pound sterling (GBP) holds about 4.8% of global allocated reserves as of early 2025, a diminished role from its historical dominance as the preeminent reserve currency under the gold standard until World War I, when it accounted for over 60% of reserves before yielding to the U.S. dollar amid Britain's war debts and imperial overextension. Post-1945, the pound's internationalization persisted through the City of London's enduring status as a global financial hub, facilitating trade invoicing and asset holdings, but its share has contracted due to the U.K.'s relative economic decline—GDP now at 3% of global output versus 25% in 1870—and events like the 1992 ERM crisis, Brexit in 2016, and resulting capital outflows that heightened volatility.[103] Empirical evidence from COFER tracks shows stability around 4-5% since the 2010s, supported by the pound's use in 7-8% of global forex turnover and its role in commodity pricing, yet causal factors such as the Bank of England's less predictable monetary policy compared to peers and geopolitical risks have limited diversification into GBP by emerging market central banks.[15] The currency's reserve utility derives from network effects in London's clearing systems, but lacks the military-backed stability or fiscal depth of the dollar, contributing to its niche positioning for European and Commonwealth-linked reserves. The Swiss franc (CHF) maintains a marginal reserve share of roughly 0.2% as of Q1 2025, far below major currencies due to Switzerland's small economy—representing under 0.5% of global GDP—despite its reputation as a premier safe-haven asset rooted in centuries of political neutrality, direct democracy, and conservative fiscal policies that have yielded average inflation below 1% since 1990. This status intensified post-2008 financial crisis, with CHF appreciating over 20% against the euro amid flight-to-quality flows, prompting Swiss National Bank (SNB) interventions exceeding 500 billion CHF in balance sheet expansion by 2015 to enforce a peg, later abandoned, highlighting tensions between haven demand and export competitiveness.[104] In 2025, ongoing geopolitical uncertainties have driven nine consecutive weekly gains in the franc versus the dollar as of October, fueled by safe-haven inflows, though the SNB's negative interest rates until 2022 and current efforts to cap appreciation underscore limits to its reserve scalability—low bond issuance volumes and reliance on franc-denominated assets deter broad central bank adoption beyond diversification portfolios.[105] Empirical correlations show CHF strengthening during equity market drawdowns, with beta coefficients to global risk indices near -0.5, affirming its causal role as a hedge, yet its reserve footprint remains constrained by the absence of deep capital markets and Switzerland's non-EU status, positioning it more as a tactical store of value than a systemic alternative.[106]Emerging Challengers

Chinese Renminbi Internationalization

China has pursued renminbi (RMB) internationalization since the late 2000s to reduce reliance on the US dollar and enhance its global financial influence, primarily through gradual liberalization measures, offshore market development, and bilateral agreements. Key initiatives include establishing offshore RMB centers, such as in Hong Kong, and launching the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) in 2015 to facilitate RMB-denominated transactions outside SWIFT. The People's Bank of China (PBOC) has signed bilateral currency swap agreements with over 40 central banks, providing access to approximately $500 billion in RMB liquidity as of early 2025, including a three-year extension with the European Central Bank in September 2025 for euro-RMB swaps.[107][108] Despite these efforts, the RMB's role in global reserves remains limited. According to IMF COFER data for Q2 2025, the RMB's allocated share in official foreign exchange reserves stood at just over 2%, a modest increase of 0.03 percentage points from the prior quarter, far behind the US dollar's approximately 58%. In international payments, SWIFT data indicate the RMB accounted for 3.17% of global value in September 2025, ranking sixth behind the dollar, euro, pound, yen, and Canadian dollar, up from 2.93% in August but still reflecting volatility and slow adoption. Trade finance shows slightly higher usage at 5.5% globally in 2024, with RMB cross-border receipts and payments involving Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) partners reaching 16.7% of China's total such flows by September 2023, though BRI settlements remain predominantly dollar-denominated due to entrenched network effects.[60][66]| Metric | RMB Share | Source/Period |

|---|---|---|

| Global Reserves (Allocated) | >2% | IMF COFER, Q2 2025[60] |

| International Payments | 3.17% | SWIFT, September 2025[66] |

| Trade Finance | 5.5% | SWIFT/IMF, 2024[109] |