Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Single-precision floating-point format

View on WikipediaThis article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: • This article doesn't provide a good structure to lead users from easy to deeper understanding • Some points are 'explained' by lengthy examples instead of concise description of the concept. (January 2025) |

Single-precision floating-point format (sometimes called FP32 or float32) is a computer number format, usually occupying 32 bits in computer memory; it represents a wide dynamic range of numeric values by using a floating radix point.

A floating-point variable can represent a wider range of numbers than a fixed-point variable of the same bit width at the cost of precision. A signed 32-bit integer variable has a maximum value of 231 − 1 = 2,147,483,647, whereas an IEEE 754 32-bit base-2 floating-point variable has a maximum value of (2 − 2−23) × 2127 ≈ 3.4028235 × 1038. All integers with seven or fewer decimal digits, and any 2n for a whole number −149 ≤ n ≤ 127, can be converted exactly into an IEEE 754 single-precision floating-point value.

In the IEEE 754 standard, the 32-bit base-2 format is officially referred to as binary32; it was called single in IEEE 754-1985. IEEE 754 specifies additional floating-point types, such as 64-bit base-2 double precision and, more recently, base-10 representations.

One of the first programming languages to provide single- and double-precision floating-point data types was Fortran. Before the widespread adoption of IEEE 754-1985, the representation and properties of floating-point data types depended on the computer manufacturer and computer model, and upon decisions made by programming-language designers. E.g., GW-BASIC's single-precision data type was the 32-bit MBF floating-point format.

Single precision is termed REAL(4) or REAL*4 in Fortran;[1] SINGLE-FLOAT in Common Lisp;[2] float binary(p) with p≤21, float decimal(p) with the maximum value of p depending on whether the DFP (IEEE 754 DFP) attribute applies, in PL/I; float in C with IEEE 754 support, C++ (if it is in C), C# and Java;[3] Float in Haskell[4] and Swift;[5] and Single in Object Pascal (Delphi), Visual Basic, and MATLAB. However, float in Python, Ruby, PHP, and OCaml and single in versions of Octave before 3.2 refer to double-precision numbers. In most implementations of PostScript, and some embedded systems, the only supported precision is single.

| Floating-point formats |

|---|

| IEEE 754 |

|

| Other |

| Alternatives |

| Tapered floating point |

IEEE 754 standard: binary32

[edit]The IEEE 754 standard specifies a binary32 as having:

- Sign bit: 1 bit

- Exponent width: 8 bits

- Significand precision: 24 bits (23 explicitly stored)

This gives from 6 to 9 significant decimal digits precision. If a decimal string with at most 6 significant digits is converted to the IEEE 754 single-precision format, giving a normal number, and then converted back to a decimal string with the same number of digits, the final result should match the original string. If an IEEE 754 single-precision number is converted to a decimal string with at least 9 significant digits, and then converted back to single-precision representation, the final result must match the original number.[6]

The sign bit determines the sign of the number, which is the sign of the significand as well. "1" stands for negative. The exponent field is an 8-bit unsigned integer from 0 to 255, in biased form: a value of 127 represents the actual exponent zero. Exponents range from −126 to +127 (thus 1 to 254 in the exponent field), because the biased exponent values 0 (all 0s) and 255 (all 1s) are reserved for special numbers (subnormal numbers, signed zeros, infinities, and NaNs).

The true significand of normal numbers includes 23 fraction bits to the right of the binary point and an implicit leading bit (to the left of the binary point) with value 1. Subnormal numbers and zeros (which are the floating-point numbers smaller in magnitude than the least positive normal number) are represented with the biased exponent value 0, giving the implicit leading bit the value 0. Thus only 23 fraction bits of the significand appear in the memory format, but the total precision is 24 bits (equivalent to log10(224) ≈ 7.225 decimal digits) for normal values; subnormals have gracefully degrading precision down to 1 bit for the smallest non-zero value.

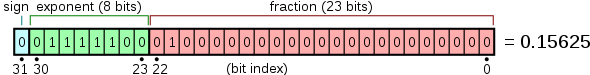

The bits are laid out as follows:

The real value assumed by a given 32-bit binary32 data with a given sign, biased exponent E (the 8-bit unsigned integer), and a 23-bit fraction is

- ,

which yields

In this example:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .

thus:

- .

Note:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .

Exponent encoding

[edit]The single-precision binary floating-point exponent is encoded using an offset-binary representation, with the zero offset being 127; also known as exponent bias in the IEEE 754 standard.

- Emin = 01H−7FH = −126

- Emax = FEH−7FH = 127

- Exponent bias = 7FH = 127

Thus, in order to get the true exponent as defined by the offset-binary representation, the offset of 127 has to be subtracted from the stored exponent.

The stored exponents 00H and FFH are interpreted specially.

| Exponent | fraction = 0 | fraction ≠ 0 | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00H = 000000002 | ±zero | subnormal number | |

| 01H, ..., FEH = 000000012, ..., 111111102 | normal value | ||

| FFH = 111111112 | ±infinity | NaN (quiet, signaling) | |

The minimum positive normal value is and the minimum positive (subnormal) value is .

Converting decimal to binary32

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (February 2020) |

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, the examples are simple particular cases (simple values exactly representable in binary, without an exponent part). This section is also probably off-topic: this is not an article about conversion, and conversion from decimal using decimal arithmetic (as opposed to conversion from a character string) is uncommon. (February 2020) |

In general, refer to the IEEE 754 standard itself for the strict conversion (including the rounding behaviour) of a real number into its equivalent binary32 format.

Here we can show how to convert a base-10 real number into an IEEE 754 binary32 format using the following outline:

- Consider a real number with an integer and a fraction part such as 12.375

- Convert and normalize the integer part into binary

- Convert the fraction part using the following technique as shown here

- Add the two results and adjust them to produce a proper final conversion

Conversion of the fractional part: Consider 0.375, the fractional part of 12.375. To convert it into a binary fraction, multiply the fraction by 2, take the integer part and repeat with the new fraction by 2 until a fraction of zero is found or until the precision limit is reached which is 23 fraction digits for IEEE 754 binary32 format.

- , the integer part represents the binary fraction digit. Re-multiply 0.750 by 2 to proceed

- , fraction = 0.011, terminate

We see that can be exactly represented in binary as . Not all decimal fractions can be represented in a finite digit binary fraction. For example, decimal 0.1 cannot be represented in binary exactly, only approximated. Therefore:

Since IEEE 754 binary32 format requires real values to be represented in format (see Normalized number, Denormalized number), 1100.011 is shifted to the right by 3 digits to become

Finally we can see that:

From which we deduce:

- The exponent is 3 (and in the biased form it is therefore )

- The fraction is 100011 (looking to the right of the binary point)

From these we can form the resulting 32-bit IEEE 754 binary32 format representation of 12.375:

Note: consider converting 68.123 into IEEE 754 binary32 format: Using the above procedure you expect to get with the last 4 bits being 1001. However, due to the default rounding behaviour of IEEE 754 format, what you get is , whose last 4 bits are 1010.

Example 1: Consider decimal 1. We can see that:

From which we deduce:

- The exponent is 0 (and in the biased form it is therefore

- The fraction is 0 (looking to the right of the binary point in 1.0 is all )

From these we can form the resulting 32-bit IEEE 754 binary32 format representation of real number 1:

Example 2: Consider a value 0.25. We can see that:

From which we deduce:

- The exponent is −2 (and in the biased form it is )

- The fraction is 0 (looking to the right of binary point in 1.0 is all zeroes)

From these we can form the resulting 32-bit IEEE 754 binary32 format representation of real number 0.25:

Example 3: Consider a value of 0.375. We saw that

Hence after determining a representation of 0.375 as we can proceed as above:

- The exponent is −2 (and in the biased form it is )

- The fraction is 1 (looking to the right of binary point in 1.1 is a single )

From these we can form the resulting 32-bit IEEE 754 binary32 format representation of real number 0.375:

Converting binary32 to decimal

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (February 2020) |

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, there is only a very simple example, without rounding. This section is also probably off-topic: this is not an article about conversion, and conversion to decimal, using decimal arithmetic, is uncommon. (February 2020) |

If the binary32 value, 41C80000 in this example, is in hexadecimal we first convert it to binary:

then we break it down into three parts: sign bit, exponent, and significand.

- Sign bit:

- Exponent:

- Significand:

We then add the implicit 24th bit to the significand:

- Significand:

and decode the exponent value by subtracting 127:

- Raw exponent:

- Decoded exponent:

Each of the 24 bits of the significand (including the implicit 24th bit), bit 23 to bit 0, represents a value, starting at 1 and halves for each bit, as follows:

bit 23 = 1 bit 22 = 0.5 bit 21 = 0.25 bit 20 = 0.125 bit 19 = 0.0625 bit 18 = 0.03125 bit 17 = 0.015625 . . bit 6 = 0.00000762939453125 bit 5 = 0.000003814697265625 bit 4 = 0.0000019073486328125 bit 3 = 0.00000095367431640625 bit 2 = 0.000000476837158203125 bit 1 = 0.0000002384185791015625 bit 0 = 0.00000011920928955078125

The significand in this example has three bits set: bit 23, bit 22, and bit 19. We can now decode the significand by adding the values represented by these bits.

- Decoded significand:

Then we need to multiply with the base, 2, to the power of the exponent, to get the final result:

Thus

This is equivalent to:

where s is the sign bit, x is the exponent, and m is the significand.

Precision limitations on decimal values (between 1 and 16777216)

[edit]- Decimals between 1 and 2: fixed interval 2−23 (1+2−23 is the next largest float after 1)

- Decimals between 2 and 4: fixed interval 2−22

- Decimals between 4 and 8: fixed interval 2−21

- ...

- Decimals between 2n and 2n+1: fixed interval 2n−23

- ...

- Decimals between 222=4194304 and 223=8388608: fixed interval 2−1=0.5

- Decimals between 223=8388608 and 224=16777216: fixed interval 20=1

Precision limitations on integer values

[edit]- Integers between 0 and 16777216 can be exactly represented (also applies for negative integers between −16777216 and 0)

- Integers between 224=16777216 and 225=33554432 round to a multiple of 2 (even number)

- Integers between 225 and 226 round to a multiple of 4

- ...

- Integers between 2n and 2n+1 round to a multiple of 2n−23

- ...

- Integers between 2127 and 2128 round to a multiple of 2104

- Integers greater than or equal to 2128 are rounded to "infinity".

Notable single-precision cases

[edit]These examples are given in bit representation, in hexadecimal and binary, of the floating-point value. This includes the sign, (biased) exponent, and significand.

|

0 00000000 000000000000000000000012 = 0000 000116 = 2−126 × 2−23 = 2−149 ≈ 1.4012984643 × 10−45 0 00000000 111111111111111111111112 = 007f ffff16 = 2−126 × (1 − 2−23) ≈ 1.1754942107 × 10−38 0 00000001 000000000000000000000002 = 0080 000016 = 2−126 ≈ 1.1754943508 × 10−38 0 11111110 111111111111111111111112 = 7f7f ffff16 = 2127 × (2 − 2−23) ≈ 3.4028234664 × 1038 0 01111110 111111111111111111111112 = 3f7f ffff16 = 1 − 2−24 ≈ 0.999999940395355225 0 01111111 000000000000000000000002 = 3f80 000016 = 1 (one) 0 01111111 000000000000000000000012 = 3f80 000116 = 1 + 2−23 ≈ 1.00000011920928955 1 10000000 000000000000000000000002 = c000 000016 = −2 0 11111111 000000000000000000000002 = 7f80 000016 = infinity 0 01111101 010101010101010101010112 = 3eaa aaab16 ≈ 0.333333343267440796 ≈ 1/3 x 11111111 100000000000000000000012 = ffc0 000116 = qNaN (on x86 and ARM processors) |

By default, 1/3 rounds up, instead of down like double-precision, because of the even number of bits in the significand. The bits of 1/3 beyond the rounding point are 1010... which is more than 1/2 of a unit in the last place.

Encodings of qNaN and sNaN are not specified in IEEE 754 and implemented differently on different processors. The x86 family and the ARM family processors use the most significant bit of the significand field to indicate a quiet NaN. The PA-RISC processors use the bit to indicate a signaling NaN.

Optimizations

[edit]The design of floating-point format allows various optimisations, resulting from the easy generation of a base-2 logarithm approximation from an integer view of the raw bit pattern. Integer arithmetic and bit-shifting can yield an approximation to reciprocal square root (fast inverse square root), commonly required in computer graphics.

See also

[edit]- ISO/IEC 10967, language independent arithmetic

- Primitive data type

- Numerical stability

- Scientific notation

References

[edit]- ^ "REAL Statement". scc.ustc.edu.cn. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ "CLHS: Type SHORT-FLOAT, SINGLE-FLOAT, DOUBLE-FLOAT..." www.lispworks.com.

- ^ "Primitive Data Types". Java Documentation.

- ^ "6 Predefined Types and Classes". haskell.org. 20 July 2010.

- ^ "Float". Apple Developer Documentation.

- ^ William Kahan (1 October 1997). "Lecture Notes on the Status of IEEE Standard 754 for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic" (PDF). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2012.

External links

[edit]Single-precision floating-point format

View on Grokipediafloat type in languages like C and C++, promoting portability across hardware while supporting operations such as rounding modes and exception flags for reliable computation.[1][6] Despite its limitations—such as rounding errors and loss of precision for very large or small numbers—it remains a foundational element in modern computing due to its compact size and widespread hardware acceleration.[7][2]

Introduction

Definition and Purpose

The single-precision floating-point format, designated as binary32 in the IEEE 754 standard, is a 32-bit computer number format designed to represent real numbers using a sign-magnitude structure with an implied leading 1 in the significand for normalized values. It allocates 1 bit for the sign, 8 bits for the biased exponent, and 23 bits for the significand (also called the mantissa), allowing for a dynamic range of approximately to and about 7 decimal digits of precision.[1] This format primarily serves to approximate continuous real numbers in computational environments where moderate precision suffices, enabling efficient storage and processing in resource-limited systems. It is widely employed in applications such as computer graphics (e.g., 3D rendering and texture mapping), scientific simulations (e.g., fluid dynamics modeling), and embedded systems (e.g., microcontrollers in consumer devices), prioritizing computational speed and memory conservation over the greater accuracy of double-precision formats.[8] Key advantages include its compact 4-byte footprint, which facilitates faster arithmetic operations through simplified hardware implementations and reduces bandwidth demands in data transfer, contrasting with the 8-byte double-precision format that demands more resources.[8] The IEEE 754 standard ensures portability and consistency in these representations across diverse hardware and software platforms.[1]Historical Development

The single-precision floating-point format emerged in the 1960s to meet the demands of scientific computing on early mainframe computers, where efficient representation of real numbers was essential for numerical simulations and engineering calculations. The IBM System/360, announced in 1964 and first delivered in 1965, popularized a 32-bit single-precision format using a hexadecimal base, featuring a 7-bit exponent and 24-bit explicit significand (fraction), normalized such that the leading hexadecimal digit is non-zero, which balanced precision and storage for both scientific and commercial applications.[9] This design addressed the prior fragmentation in floating-point implementations across vendors, enabling more portable software for tasks like physics modeling and data analysis, though its base-16 encoding led to unique rounding behaviors compared to binary formats.[10] By the 1970s, the proliferation of vendor-specific formats—such as DEC's VAX binary floating-point with abrupt underflow handling and Cray's sign-magnitude representation with abrupt underflow handling (lacking gradual underflow)—created significant portability issues for scientific software, prompting calls for standardization to ensure reproducible results across systems.[11] The IEEE 754 standard, developed by the IEEE Floating-Point Working Group starting in 1977 under the leadership of figures like William Kahan (often called the "Father of Floating Point"), culminated in its 1985 publication, defining binary32 as the single-precision interchange format with 1 sign bit, 8-bit biased exponent, and 23-bit significand for consistent arithmetic operations.[11] Kahan's influence emphasized gradual underflow and exception handling to control rounding errors, drawing from experiences with IBM, Cray, and DEC systems to prioritize reliability in numerical computations.[11] Adoption accelerated in the late 1980s with hardware implementations, notably Intel's 80387 math coprocessor released in 1987, which provided full compliance for x86 systems and facilitated widespread use in personal computing for engineering and graphics.[12] By the 1990s and 2000s, single-precision binary32 became integral to graphics processing units (GPUs), as seen in NVIDIA's CUDA architecture supporting IEEE 754 operations for parallel scientific workloads, and mobile devices, where ARM-based processors leverage it for efficient real-time computations in embedded systems.[13] This standardization transformed floating-point from a "zoo" of incompatible formats into a universal foundation for portable, high-performance computing.[14]IEEE 754 Binary32 Format

Bit Layout

The single-precision floating-point format, also known as binary32 in the IEEE 754 standard, allocates 32 bits across three distinct fields to encode the sign, exponent, and significand of a number. The sign field occupies 1 bit (bit 31, the most significant bit), the exponent field uses 8 bits (bits 30 through 23), and the significand field comprises the remaining 23 bits (bits 22 through 0). This structure enables the representation of a wide range of real numbers with a balance of precision and dynamic range.[15] The bit layout can be visualized as follows, where the fields are shown from the most significant bit (left) to the least significant bit (right):s eeeeeeee mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm

s eeeeeeee mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm

s denotes the sign bit, eeeeeeee represents the 8 exponent bits, and mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm indicates the 23 significand bits. This notation illustrates the sequential arrangement within the 32-bit word.[16]

For normalized numbers, the significand field stores the fractional part following an implicit leading bit of 1, effectively yielding 24 bits of precision in the significand. This hidden bit is not explicitly stored but is assumed during decoding to normalize the representation.[15]

Although diagrams conventionally depict the bit layout in big-endian order—with the sign bit in the highest-addressed byte—the actual storage in memory follows the endianness of the host platform's architecture, as the IEEE 754 standard does not prescribe a specific byte ordering.[17]

Sign Bit

In the single-precision floating-point format defined by IEEE 754, the sign bit occupies the most significant bit position, bit 31, within the 32-bit representation. This bit determines the polarity of the represented number: a value of 0 indicates a non-negative quantity, encompassing positive numbers, +0, and +∞, while a value of 1 denotes a negative quantity, including negative numbers, -0, and -∞. The sign bit operates independently of the magnitude encoded in the exponent and significand fields, serving solely to apply a multiplicative factor of (-1) raised to the power of the sign bit value to the overall numerical interpretation. This design preserves the absolute value derived from the remaining bits, allowing the format to represent both positive and negative versions of the same magnitude without altering the underlying structure. Historically, the inclusion of a dedicated sign bit in this manner addressed limitations in earlier floating-point formats, such as those used in IBM systems during the 1950s and 1960s, which often suffered from asymmetric handling of signs or redundant representations like negative zero that complicated arithmetic operations.[11] By standardizing a sign-magnitude approach, IEEE 754 ensured symmetric treatment of positive and negative real numbers, promoting consistent behavior across implementations and mitigating portability issues prevalent in pre-standard hardware.[18] A practical illustration of the sign bit's role is in distinguishing signed zeros: the bit pattern 0x00000000 (all bits zero) represents +0, whereas 0x80000000 (only bit 31 set to 1) represents -0, with these values comparing equal in equality comparisons but differing in certain sign-dependent operations like division by zero (e.g., 1 / +0 = +∞ and 1 / -0 = -∞).[19]Exponent Field

In the IEEE 754 binary32 format, the exponent field occupies 8 bits, positioned as bits 30 through 23 (with bit 30 as the most significant). This field encodes the scaling factor of the floating-point number using a biased representation, which shifts the exponent values to allow storage in an unsigned binary format.[20] The bias value is 127, such that the stored exponent relates to the true exponent by the formula , or equivalently, . This encoding ensures that the exponent field can represent both positive and negative powers of 2 without dedicating a separate sign bit to the exponent itself.[3] For normal numbers, the exponent field holds values from 1 to 254 (in decimal), yielding true exponents from -126 to +127 and enabling the representation of numbers in the range approximately to . The value 0 in the exponent field is reserved for subnormal numbers and zero, while 255 (all bits set to 1) indicates infinity or NaN (not-a-number) values.[21] The use of biasing simplifies hardware implementations for operations like magnitude comparisons, as the biased exponents can be directly compared as unsigned integers without adjustment, promoting efficiency in arithmetic pipelines.[3]Significand Field

The significand field in the IEEE 754 binary32 format consists of 23 explicit bits, labeled as bits 22 through 0, which store the fractional part of the normalized significand.[22] For normalized numbers, an implicit leading bit of 1 is assumed before the binary point, effectively providing 24 bits of precision; this leading 1 is not stored to maximize the use of available bits for the fractional components.[6] The value of the significand is thus represented as $1.mm$ denotes the 23-bit binary fraction formed by the explicit bits.[23] In the case of denormalized (subnormal) numbers, which occur when the exponent field is all zeros and the significand field is non-zero, there is no implicit leading 1; instead, the significand is interpreted as $0.m$, starting with a leading zero and using only the explicit 23 bits for precision.[24] This design choice allows representation of values closer to zero than would be possible with normalized numbers but at the cost of reduced precision, as the effective number of significant bits decreases depending on the position of the leading 1 in the fraction.[25] Overall, the 24-bit precision of normalized binary32 significands corresponds to approximately 7 decimal digits of accuracy, sufficient for many scientific and engineering applications while balancing storage efficiency.[26]Number Representation

Normal Numbers

In the IEEE 754 binary32 format, normal numbers represent the majority of finite, non-zero floating-point values, utilizing the full available precision through a normalized significand and an exponent field that excludes the all-zero and all-one patterns reserved for subnormals and special values.[15] Normalization ensures the significand is adjusted by left-shifting the binary representation until the leading bit is 1, placing the binary point immediately after this implicit leading 1, while simultaneously decrementing the exponent to maintain the value; this process maximizes the precision by avoiding leading zeros in the significand.[15][3] The value of such a normal number is calculated aswhere is the sign bit (0 for positive, 1 for negative), is the 8-bit exponent field interpreted as an unsigned integer ranging from 1 to 254, and is the 23-bit significand field interpreted as an unsigned integer from 0 to ; the term incorporates the implicit leading 1 for the normalized significand.[15][3] This representation allows positive normal numbers to span from the smallest magnitude of approximately (when and , yielding ) to the largest finite magnitude of approximately (when and , yielding nearly ), with negative counterparts symmetric about zero.[15][3] A representative example is the decimal value 1.0, which in binary32 is encoded as the hexadecimal 3F800000: the sign bit , the biased exponent (binary 01111111, corresponding to unbiased exponent 0), and significand field (implying the normalized significand 1.0).[15][3]

Subnormal Numbers

Subnormal numbers in the single-precision IEEE 754 binary32 format represent values smaller in magnitude than the smallest normal number, enabling finer granularity near zero. They occur when the 8-bit exponent field is all zeros (unbiased exponent of -126) and the 23-bit significand field is non-zero.[27] The numerical value of a subnormal number is calculated as where is the sign bit (0 for positive, 1 for negative) and is the integer represented by the 23 significand bits (ranging from 1 to ). Unlike normal numbers, which include an implicit leading 1 in the significand, subnormals explicitly start with a leading 0, effectively treating the significand as a fraction less than 1.[27] This mechanism supports gradual underflow, allowing a smooth transition from normal numbers to zero rather than an abrupt gap, which improves numerical stability and precision in computations involving very small quantities.[27] The positive subnormal numbers range from the tiniest value of approximately to just under , with precision diminishing toward the smaller end due to the leading zero in the significand, which reduces the effective number of significant bits.[27] For instance, the smallest positive subnormal, encoded as the hexadecimal value 0x00000001 (significand bits representing ), equals .[27]Special Values

In the IEEE 754 binary32 format, special values represent non-finite quantities essential for handling exceptional conditions in floating-point arithmetic. These include signed zero, infinity, and Not a Number (NaN), each defined by specific bit patterns in the sign, exponent, and significand fields.[28] Signed zero is encoded with an exponent of 0 and a significand of 0, resulting in the bit patterns 0x00000000 for positive zero (+0) and 0x80000000 for negative zero (-0), where the sign bit determines the polarity. Although +0 and -0 compare equal in arithmetic operations and ordering, they differ in certain contexts, such as reciprocals where 1 / -0 yields -∞ while 1 / +0 yields +∞. The sign bit plays a crucial role in distinguishing these representations for signed zeros and infinities.[28][28] Infinity is represented with an exponent of all 1s (255 in biased form) and a significand of 0, corresponding to 0x7F800000 for positive infinity (+∞) and 0xFF800000 for negative infinity (-∞). These values arise from operations like overflow in multiplication or addition, or division of a nonzero finite number by zero, such as 1.0 / 0.0 producing +∞. Infinities propagate through arithmetic while preserving the sign, though operations like ∞ - ∞ signal an invalid condition.[28][28] NaN, or Not a Number, uses an exponent of 255 and a nonzero significand, allowing for 2^{23} - 1 possible nonzero significand patterns (sign bit typically ignored). The most significant bit of the significand distinguishes quiet NaNs (qNaN, with this bit set to 1, e.g., 0x7FC00000) from signaling NaNs (sNaN, with this bit 0); qNaNs propagate silently through operations without raising exceptions, while sNaNs trigger an invalid operation exception. The remaining lower bits serve as a payload for diagnostic information, such as identifying the source of the error. NaNs are generated by invalid operations, for example, the square root of -1 yielding a NaN, and they are unordered in comparisons, so NaN ≠ NaN. The sign bit for NaNs is ignored in most operations.[28][28]Conversions

Decimal to Binary32

Converting a decimal number to the binary32 format, as defined in the IEEE 754 standard, requires a systematic process to encode the value using 1 sign bit, an 8-bit biased exponent, and a 23-bit significand field. This ensures finite numbers are represented in normalized or subnormal form, while handling extremes like overflow to infinity or underflow to zero or subnormals. The process prioritizes exact representation when possible, with rounding applied for inexact values to maintain precision.[27] The conversion begins by isolating the sign: for a positive decimal number, the sign bit is set to 0; for negative, it is 1. The absolute value is then converted to binary representation. To achieve this manually, separate the integer and fractional parts. The integer part is converted by repeated division by 2, recording remainders as bits from least to most significant. The fractional part is converted by repeated multiplication by 2, recording the integer part (0 or 1) after the decimal point until the fraction terminates, repeats, or sufficient bits are obtained. These binary parts are combined to form the full binary equivalent.[23][29] Next, normalize the binary value to scientific notation of the form , where is the fractional significand (0 ≤ m < 1) and is the unbiased exponent. This involves shifting the binary point left or right until the leading bit is 1, adjusting by the number of shifts (positive for right shifts, negative for left). For values too small to normalize with , a subnormal form is used with an explicit leading 0 in the significand and . The biased exponent is then computed as , encoded in 8 bits (ranging from 1 to 254 for normals, 0 for subnormals).[27][3] The significand field captures the 23 bits of after the implicit leading 1 (for normals) or explicit bits (for subnormals). If the binary fraction exceeds 23 bits, round to the nearest representable value using the default round-to-nearest, ties-to-even mode, in which exact ties (halfway cases) are rounded to make the least significant bit of the significand even. The full 32-bit representation is assembled as sign (1 bit) + biased exponent (8 bits) + significand (23 bits).[27][23] For large decimals where the unbiased exponent , the result overflows to positive or negative infinity (sign bit accordingly, exponent all 1s or 255, significand 0). For very small decimals where the magnitude is less than the smallest subnormal (), it underflows to zero. These behaviors preserve computational integrity by signaling unbounded or negligible values.[27][23]Example: Converting 12.375

Consider the decimal 12.375, which is positive (sign bit = 0).- Binary conversion: Integer 12 = 1100, fraction 0.375 = 0.011 (0.375 × 2 = 0.75 → 0; 0.75 × 2 = 1.5 → 1; 0.5 × 2 = 1.0 → 1). Combined: 1100.011.

- Normalization: Shift binary point 3 places left to 1.100011 × 2, so .

- Biased exponent: .

- Significand: Fractional bits 100011, padded with 17 zeros to 23 bits: 10001100000000000000000 (no rounding needed).

- Full binary32: 0 10000010 10001100000000000000000, or in hexadecimal 0x41460000.[23][29]

Binary32 to Decimal

The process of converting a binary32 representation to a decimal value, known as decoding, involves parsing the 32-bit field into its components and reconstructing the numerical value according to the IEEE 754 standard. This decoding reverses the encoding process by interpreting the sign bit, biased exponent, and significand to yield either an exact decimal equivalent (for special cases) or an approximation of the represented real number.[23] The first step is to extract the components from the 32-bit binary string: the sign bit s (bit 31, where 0 indicates positive and 1 negative), the 8-bit biased exponent E (bits 30–23, an unsigned integer from 0 to 255), and the 23-bit significand M (bits 22–0, treated as an integer fraction).[23][3] Next, classify the number based on the exponent E:- If E = 0 and M = 0, the value is zero: . The sign bit distinguishes +0 from -0, though they are equal in most arithmetic operations.[23]

- If E = 0 and M ≠ 0, it is a subnormal number, used to represent values closer to zero than normal numbers can: . Here, there is no implicit leading 1 in the significand, allowing gradual underflow.[23]

- If E = 255 and M = 0, the value is infinity: . Positive infinity results from overflow or division by zero in certain contexts, and negative infinity similarly.[23]

- If E = 255 and M ≠ 0, it is a Not-a-Number (NaN) value, signaling invalid operations like square root of a negative number. NaNs are neither positive nor negative, and the sign bit is ignored in output; they are typically rendered as the string "NaN". The significand bits may encode diagnostic information, but this is implementation-dependent.[23]

- Otherwise, for 1 ≤ E ≤ 254, it is a normal number: . The unbiased exponent is E - 127 (the bias for binary32), and the significand is normalized with an implicit leading 1 prepended to M.[23][3]

Precision and Limitations

Integer Precision Limits

The single-precision floating-point format, standardized in IEEE 754, utilizes a 24-bit significand (23 explicitly stored bits plus one implicit leading bit) that enables the exact representation of all integers from to , inclusive. This range spans from -16,777,216 to 16,777,216, as the significand's precision accommodates up to 24 binary digits without requiring fractional components for these values.[19][30] For integers satisfying , every integer is uniquely and exactly representable in binary32 format, ensuring no loss of information during conversion from integer to floating-point representation within this bound. Beyond this threshold, the unit in the last place (ulp) exceeds 1, introducing gaps in representable values; for instance, in the interval , the ulp is 2, meaning only even integers are exactly representable, while odd integers round to the nearest even value. Gaps widen further at higher magnitudes, up to the format's maximum exponent, though single-precision operations on values approaching double-precision's 53-bit integer limit (2^{53}) would involve additional rounding errors specific to binary32.[19][30] A concrete example illustrates this limitation: the integer 16,777,215 () is exactly representable, as is 16,777,216 (), but 16,777,217 () cannot be distinguished and rounds to 16,777,216 in binary32 under round-to-nearest-ties-to-even. The next representable integer is 16,777,218, which is exactly representable, demonstrating the loss of resolution for consecutive integers just beyond the exact range.[19] These precision constraints make single-precision suitable for exact arithmetic on 24-bit integers, such as in embedded systems or graphics processing where such ranges suffice, but operations involving larger integers in floating-point contexts introduce inaccuracies, potentially requiring higher-precision formats like double for fidelity.[30]Decimal Precision Limits

The single-precision floating-point format provides approximately 7 decimal digits of precision, equivalent to the logarithmic base-10 value of its 24-bit significand (23 stored bits plus 1 implicit leading bit).[26][22] This level of precision means that decimal numbers exceeding 7 significant digits are subject to approximation, as the binary representation cannot capture all possible decimal fractions exactly. A key limitation is the inability to represent certain simple decimal fractions precisely, such as 0.1, whose binary expansion is non-terminating and recurring: .[31] In single-precision, 0.1 is rounded to the nearest representable value, 0.10000000149011612 (in hexadecimal, 0x3DCCCCCD), introducing an absolute error of approximately .[32] Within the normalized range from 1 to (about 16,777,216), the unit in the last place (ulp) is , allowing many decimal values with up to 6 digits after the decimal point to be distinguished, but not all multiples of are exact due to the binary radix.[3] For example, even in this range, 0.1 retains its rounding error of about , as the denominator 10 introduces factors of 5 that do not align with powers of 2.[32] Illustrative cases highlight the precision boundary: the 7-digit decimal 1.234567 is stored as approximately 1.23456705, already an approximation with an error on the order of .[32] Extending to 8 digits, 1.23456789 rounds to about 1.23456788, demonstrating loss of fidelity in the final digit.[32] These issues commonly affect decimals with denominators containing prime factors other than 2 (e.g., 1/3 or 1/10), which expand to infinite binary fractions and must be truncated or rounded to fit the 23-bit mantissa, propagating small but cumulative errors in computations.[31] Subnormal numbers briefly extend precision limits for tiny decimals near zero, though with fewer effective bits in the significand.[22]Rounding and Error Handling

The IEEE 754 standard for binary floating-point arithmetic defines four rounding modes to handle inexact results during operations such as addition, multiplication, and conversion.[33] These modes determine how a result is adjusted to the nearest representable value when the exact mathematical outcome cannot be precisely encoded in the binary32 format. The default mode is round to nearest, with ties rounded to the even least significant bit (also known as roundTiesToEven), which minimizes accumulation of rounding errors over multiple operations by alternating rounding direction in tie cases.[30] The other modes are round toward zero (truncation, discarding excess bits), round toward positive infinity (rounding up for positive numbers and down for negative), and round toward negative infinity (rounding down for positive numbers and up for negative).[34] Implementations must support dynamic switching between these modes to allow precise control in numerical computations.[33] Errors in single-precision arithmetic primarily arise from rounding during the normalization of intermediate results or conversions between formats, measured relative to the unit in the last place (ulp), which is the difference between two consecutive representable values at a given magnitude.[30] In multiplications and additions, these rounding errors can accumulate, leading to relative errors bounded by 0.5 ulp per operation in the round-to-nearest mode, though repeated operations may amplify discrepancies in sensitive algorithms like iterative solvers.[30] The ulp concept quantifies precision loss, as single-precision's 24-bit significand (including the implicit leading 1) limits exact representation to values up to about 2^{24}, beyond which spacing between representables increases.[30] Overflow occurs when the result's magnitude exceeds the maximum representable value (approximately 3.4028235 × 10^{38}), producing positive or negative infinity depending on the sign, with an optional overflow exception flag.[33] Underflow happens for results smaller than the smallest normalized number (about 1.1754944 × 10^{-38}), where the standard mandates gradual underflow to subnormal numbers to preserve small values and reduce abrupt error jumps, though some implementations offer an optional "flush to zero" mode for performance in non-critical applications.[33] These mechanisms ensure predictable behavior, with underflow exceptions signaled only if the result is inexact and tiny.[35] A classic illustration of rounding error in the default round-to-nearest mode is the addition of 0.1 and 0.2, which yields approximately 0.300000004 rather than exactly 0.3, due to the inexact binary representations of these decimals (0.1 ≈ 0.10000000149011612 and 0.2 ≈ 0.20000000298023224 in binary32) requiring rounding of their sum.[30] This discrepancy, on the order of 4 × 10^{-9}, highlights how decimal fractions often introduce ulp-level errors in binary floating-point, emphasizing the need for careful mode selection in applications demanding high fidelity.[30]Applications and Optimizations

Common Use Cases

Single-precision floating-point format, also known as FP32, is extensively utilized in graphics and gaming applications for its balance of performance and sufficient accuracy in real-time rendering. In OpenGL, vertex positions and attributes are commonly specified using 32-bit single-precision floats through APIs like glVertexAttribPointer, enabling efficient processing of geometric data such as positions, normals, and texture coordinates.[36] Similarly, Direct3D 11 mandates adherence to IEEE 754 32-bit single-precision rules for all floating-point operations in shaders, ensuring consistent behavior across hardware for tasks like vertex transformations and pixel shading in DirectX pipelines.[37] Graphics processing units (GPUs) from NVIDIA, for example, optimize FP32 throughput in shaders, delivering high teraflops performance tailored to the demands of 3D rendering and gaming workloads.[38] In embedded systems, FP32 is favored for its compact 32-bit representation, which aligns with memory constraints in microcontrollers while supporting hardware-accelerated operations. The ARM Cortex-M4 processor includes a single-precision floating-point unit (FPU) that enables efficient handling of sensor data processing, such as analog-to-digital conversions and signal filtering, without the overhead of double-precision emulation. Platforms like Arduino boards with ARM-based cores, such as the Arduino Uno R4 which uses a Renesas RA4M1 (Cortex-M4F with FPU), leverage FP32 for real-time control tasks where storage efficiency is critical, avoiding the doubled memory footprint of 64-bit doubles. This format proves adequate for applications involving environmental monitoring or IoT devices, where precision beyond six decimal digits is rarely needed. Machine learning inference on edge devices commonly employs FP32 to maintain model accuracy while fitting within limited computational resources. TensorFlow Lite, optimized for mobile and embedded deployment, defaults to single-precision floats for weights, activations, and computations, allowing efficient execution of neural networks on devices like smartphones or microcontrollers without significant quantization artifacts. For instance, in vision-based tasks on edge hardware, FP32 supports forward passes at speeds suitable for real-time applications, such as object detection in constrained environments. Scientific simulations often adopt single-precision for scenarios where speed outweighs marginal precision gains, particularly in large-scale computations. Weather forecasting models, like the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts' Integrated Forecasting System (IFS), use FP32 to reduce computational costs by up to 40% at resolutions around 50 km, with negligible impact on forecast skill scores compared to double-precision runs.[39] In physics engines for simulations, FP32 facilitates rapid iterations in rigid body dynamics and collision detection, prioritizing throughput in time-sensitive analyses. MATLAB's single-precision mode further exemplifies this, enabling faster matrix operations and simulations in fields like fluid dynamics, where hardware acceleration amplifies performance benefits. A key trade-off with FP32 is its potential for accumulated rounding errors in iterative calculations, which can be up to twice as fast as double-precision on consumer GPUs but may necessitate higher-precision alternatives in accuracy-critical domains. In high-accuracy needs, these precision limitations briefly warrant evaluation against double-precision formats.Hardware and Software Optimizations

Single-precision floating-point operations benefit from hardware accelerations in modern processors, particularly through single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) extensions that enable vectorized computations. On x86 architectures, Intel's AVX-512 instruction set processes up to 16 single-precision elements simultaneously within 512-bit registers, delivering peak throughputs of up to 32 fused multiply-add (FMA) operations per cycle on processors with dual FMA units, such as those in the Xeon Scalable family.[40] This vectorization significantly boosts performance in workloads like scientific simulations and machine learning inference, where parallel floating-point arithmetic dominates. Similarly, AMD's Zen architectures incorporate AVX2 and AVX-512 support, achieving comparable single-precision vector FLOPS rates through wide execution units optimized for FP32 data paths. Graphics processing units (GPUs) further enhance single-precision efficiency via dedicated floating-point units (FPUs). NVIDIA's CUDA cores, the fundamental compute elements in GPUs like the A100, are explicitly tuned for FP32 operations, supporting high-throughput parallel execution with rates exceeding 19.5 teraFLOPS on such hardware, making them ideal for graphics rendering and general-purpose computing.[41] These cores handle scalar and vector FP32 math natively, often outperforming CPU SIMD in massively parallel scenarios by leveraging thousands of threads. In conjunction with Tensor Cores, which perform FP16 multiplies followed by FP32 accumulation, CUDA cores ensure seamless FP32 handling for precision-critical steps, amplifying overall system performance in compute-intensive tasks.[41] Software optimizations complement hardware by strategically managing precision to maximize speed without compromising reliability. In deep learning, mixed-precision training employs FP32 for weight updates and gradient accumulations to maintain numerical stability, while using FP16 for forward and backward passes to accelerate computations and reduce memory bandwidth—yielding up to 3x speedups on NVIDIA GPUs with Tensor Core support.[42] This approach, detailed in seminal work on automatic mixed-precision frameworks, preserves model accuracy comparable to full FP32 training while enabling larger batch sizes.[43] Libraries like cuBLAS facilitate these gains through batched single-precision operations, such ascublasSgemmBatched, which execute multiple independent matrix multiplies concurrently across GPU streams, ideal for small-matrix workloads in simulations and AI.[44]

Additional techniques focus on minimizing overhead in FP32 pipelines. Avoiding conversions from double-precision (FP64) to single-precision is crucial, as such casts introduce latency and register pressure on hardware where FP32 paths are faster and more abundant—potentially halving execution time in embedded or GPU contexts by staying within native single-precision domains.[45] Similarly, enabling flush-to-zero (FTZ) mode disables gradual underflow for subnormal numbers, which can cause up to 125x slowdowns in FP32 operations due to exception handling; on Intel Xeon processors, FTZ yields nearly 2x speedup in parallel applications with minimal accuracy impact for most use cases.[46]

Notable implementations highlight these optimizations in practice. The fast inverse square root algorithm in Quake III Arena approximates using a single-precision bit-level hack followed by one Newton-Raphson iteration, delivering four times the speed of standard library calls for real-time lighting and normalization in 3D graphics.[47] In mobile VR and AR, single-precision's efficiency enables low-latency rendering on power-limited GPUs like ARM Mali, balancing 24-bit mantissa accuracy with reduced energy consumption for immersive experiences on devices such as smartphones.[48]

![{\displaystyle 1.b_{22}b_{21}...b_{0}=1+\sum _{i=1}^{23}b_{23-i}2^{-i}=1+1\cdot 2^{-2}=1.25\in \{1,1+2^{-23},\ldots ,2-2^{-23}\}\subset [1;2-2^{-23}]\subset [1;2)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c8b8c401c6cf3993878f339f4a19970db99f883)