Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

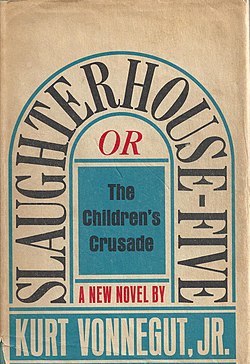

Slaughterhouse-Five

View on Wikipedia

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut. It follows the life experiences of Billy Pilgrim, from his early years, to his time as an American soldier and chaplain's assistant during World War II, to the post-war years. Throughout the novel, Billy frequently travels back and forth through time. The protagonist deals with a temporal crisis as a result of his post-war psychological trauma. The text centers on Billy's capture by the German Army and his survival of the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience that Vonnegut endured as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of "unmatched moral clarity"[3] and "one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time".[3]

Key Information

Plot

[edit]The novel's first chapter begins with "All this happened, more or less"; this introduction implies that an unreliable narrator tells the story. Vonnegut utilizes a non-linear, non-chronological description of events to reflect Billy Pilgrim's psychological state. Events become clear through flashbacks and descriptions of time travel experiences.[4] In the first chapter, the narrator describes his writing of the book, his experiences as a University of Chicago anthropology student and a Chicago City News Bureau correspondent, his research on the Children's Crusade and the history of Dresden, and his visit to Cold War–era Europe with his wartime friend Bernard V. O'Hare. In the second chapter, Vonnegut introduces Billy Pilgrim, an American man from the fictional town of Ilium, New York. Billy believes that an extraterrestrial species from the planet Tralfamadore held him captive in an alien zoo and that he has experienced time travel.

As a chaplain's assistant in the United States Army during World War II, Billy is an ill-trained, disoriented and fatalistic American soldier who discovers that he does not like war and refuses to fight.[5] He is transferred from a base in South Carolina to the front line in Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge. He narrowly escapes death as the result of a string of events. He also meets Roland Weary, a patriot, warmonger, and sadistic bully who derides Billy's cowardice. The two of them are captured in 1944 by the Germans, who confiscate all of Weary's belongings and force him to wear wooden clogs that cut painfully into his feet; the resulting wounds become gangrenous, which eventually kills him. While Weary is dying in a rail car full of prisoners, he convinces a fellow soldier, Paul Lazzaro, that Billy is to blame for his death. Lazzaro vows to avenge Weary's death by killing Billy, because revenge is "the sweetest thing in life."

At this exact time, Billy becomes "unstuck in time"; Billy travels through time to moments from his past and future. The novel describes the transportation of Billy and the other prisoners into Germany. The German soldiers held their prisoners in the German city of Dresden; the prisoners had to work in "contract labor" (forced labor); these events occurred in 1945. The Germans detained Billy and his fellow prisoners in an empty slaughterhouse called Schlachthof-fünf ("slaughterhouse five"). During the Allied bombing of Dresden, German guards hid their captives in the partially underground setting of the slaughterhouse; this protected those captives from complete annihilation. As a result, they are among the few survivors of the firestorm that raged in the city between February 13 and 15, 1945. After V-E Day in May 1945, Billy was transferred to the United States and received an honorable discharge in July 1945.

Billy is hospitalized with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder and placed under psychiatric care at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Lake Placid. During Billy's stay at the hospital, Eliot Rosewater introduces him to the work of an obscure science fiction writer named Kilgore Trout. After his release, Billy marries Valencia Merble, whose father owns the Ilium School of Optometry that Billy later attends. Billy becomes a successful and wealthy optometrist. In 1947, Billy and Valencia conceive their first child, Robert, on their honeymoon in Cape Ann, Massachusetts. Two years later, their second child, Barbara, was born. On Barbara's wedding night, Billy is abducted by a flying saucer and taken to a planet many light-years away from Earth called Tralfamadore. The Tralfamadorians have the power to see in four dimensions; they simultaneously observe all points in the space-time continuum. They universally adopt a fatalistic worldview: death means nothing to them, and their typical response to hearing about death is "so it goes."

The Tralfamadorians transport Billy to Tralfamadore and place him inside a transparent geodesic dome exhibit in a zoo; the inside resembles a house on planet Earth. The Tralfamadorians later abduct a pornographic film star named Montana Wildhack, who had disappeared on Earth and supposedly drowned in San Pedro Bay. The Tralfamadorians intend to have her mate with Billy. Montana and Billy fall in love and have a child together. Billy is instantaneously sent back to Earth in a time warp to re-live past or future moments of his life.

In 1968, Billy and a co-pilot are the only survivors of a plane crash in Vermont. While driving to visit Billy in the hospital, Valencia crashes her car and dies of carbon monoxide poisoning. Billy shares a hospital room with Bertram Rumfoord, a Harvard University history professor researching an official war history of the USAAF in World War II. They discuss the bombing of Dresden, which the professor initially refuses to believe Billy witnessed. Despite the significant loss of civilian life and the destruction of Dresden, they both regard the bombing as a justifiable act.

Billy's daughter takes him home to Ilium. He escapes and flees to New York City. In Times Square he visits a pornographic book store, where he discovers books written by Kilgore Trout and reads them. He discovers a science fiction novel titled The Big Board at the bookstore. The novel is about a couple abducted by extraterrestrials. The aliens trick the abductees into thinking they are managing investments on Earth, which excites the humans and, in turn, sparks interest in the observers. He also finds some magazine covers that mention Montana Wildhack's disappearance. While Billy surveys the bookstore, one of Montana's pornographic films plays in the background. Later in the evening, when he discusses his time travels to Tralfamadore on a radio talk show, he is ejected from the studio. He returns to his hotel room, falls asleep, and time-travels back to 1945 in Dresden. Billy and his fellow prisoners are tasked with locating and burying the dead. After a Maori New Zealand soldier working with Billy dies of dry heaves the Germans begin cremating the bodies en masse with flamethrowers. German soldiers execute Billy's friend Edgar Derby for stealing a teapot. Eventually all of the German soldiers leave to fight on the Eastern Front, leaving Billy and the other prisoners alone with tweeting birds as the war ends.

Through non-chronological storytelling, other parts of Billy's life are told throughout the book. After Billy is evicted from the radio studio, Barbara treats Billy as a child and often monitors him. Robert becomes starkly anti-communist, enlists as a Green Beret and fights in the Vietnam War. Billy is eventually killed in 1976, at which point the United States has been partitioned into twenty countries and attacked by China with thermonuclear weapons. He gives a speech in a baseball stadium in Chicago in which he predicts his own death and proclaims that "if you think death is a terrible thing, then you have not understood a word I've said." Billy soon after is shot with a laser gun by an assassin commissioned by the elderly Lazzaro.

Characters

[edit]

- Narrator: Recurring as a minor character, the narrator seems anonymous while also clearly identifying himself as Kurt Vonnegut, when he says, "That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book."[6] As noted above, as an American soldier during World War II, Vonnegut was captured by Germans at the Battle of the Bulge and transported to Dresden. He and fellow prisoners-of-war survived the bombing while being held in a deep cellar of Schlachthof Fünf ("Slaughterhouse-Five").[7] The narrator begins the story by describing his connection to the firebombing of Dresden and his reasons for writing Slaughterhouse-Five.

- Billy Pilgrim: A fatalistic optometrist ensconced in a dull, safe marriage in Ilium, New York. During World War II, he was held as a prisoner-of-war in Dresden and survived the firebombing, experiences which had a lasting effect on his post-war life. His time travel occurs at desperate times in his life; he relives past and future events and becomes fatalistic (though not a defeatist) because he claims to have seen when, how and why he will die.

- Roland Weary: A weak man dreaming of grandeur and obsessed with gore and vengeance, who saves Billy several times (despite Billy's protests) in hopes of attaining military glory. He coped with his unpopularity in his home city of Pittsburgh by befriending and then beating people less well-liked than him, and is obsessed with his father's collection of torture equipment. Weary is also a bully who beats Billy and gets them both captured, leading to the loss of his winter uniforms and boots. Weary dies of gangrene on the train en route to the POW camp, and blames Billy in his dying words.

- Paul Lazzaro: Another POW. A sickly, ill-tempered car thief from Cicero, Illinois who takes Weary's dying words as a revenge commission to kill Billy. He keeps a mental list of his enemies, claiming he can have anyone "killed for a thousand dollars plus traveling expenses." Lazzaro eventually fulfills his promise to Weary and has Billy assassinated by a laser gun in 1976.

- Kilgore Trout: A failed science fiction writer whose hometown is also Ilium, New York, and who makes money by managing newspaper delivery boys. He has received only one fan letter (from Eliot Rosewater; see below). After Billy meets him in a back alley in Ilium, he invites Trout to his wedding anniversary celebration. There, Kilgore follows Billy, thinking the latter has seen through a "time window." Kilgore Trout is also a main character in Vonnegut's 1973 novel Breakfast of Champions.

- Edgar Derby: A middle-aged high school teacher who felt that he needed to participate in the war rather than just send off his students to fight. One of his sons is serving with the marines in the Pacific Theatre. Though relatively unimportant, Derby seems to be the only American before the bombing of Dresden to understand what war can do to people. During Campbell's presentation he stands up and castigates him, defending American democracy and the alliance with the Soviet Union. German forces summarily execute him for looting after they catch him taking a teapot from catacombs after the bombing. The undamaged teapot is identical to one he has at home, and it is his astonishment at the find amongst the rubble, that gives him away to the guards. Vonnegut has said that this death is the climax of the book as a whole.

- Howard W. Campbell Jr.: An American-born Nazi. Before the war, he lived in Germany where he was a noted German-language playwright recruited by the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda. In an essay, he connects the misery of American poverty to the disheveled appearance and behavior of the American POWs. Edgar Derby confronts him when Campbell tries to recruit American POWs into the American Free Corps to fight the Communist Soviet Union on behalf of the Nazis. He appears wearing swastika-adorned cowboy hat and boots and with a red, white and blue Nazi armband. Campbell is the protagonist of Vonnegut's 1962 novel Mother Night.

- Valencia Merble: Billy's wife and the mother of their children, Robert and Barbara. Billy is emotionally distant from her. She dies from carbon monoxide poisoning after an automobile accident en route to the hospital to see Billy after his airplane crash.

- Robert Pilgrim: Son of Billy and Valencia. A troubled, middle-class boy and disappointing son who becomes an alcoholic at age 16, drops out of high school, and is arrested for vandalizing a Catholic cemetery. He later so absorbs the anti-Communist worldview that he metamorphoses from suburban adolescent rebel to Green Beret sergeant. He wins a Purple Heart, Bronze Star and Silver Star in the Vietnam War.

- Barbara Pilgrim: Daughter of Billy and Valencia. She is a "bitchy flibbertigibbet" from having had to assume the family's leadership at the age of twenty. She has "legs like an Edwardian grand piano," marries an optometrist, and treats her widowed father as a childish invalid.

- Tralfamadorians: The race of extraterrestrial beings who appear (to humans) like upright toilet plungers with a hand atop, in which is set a single green eye. They abduct Billy and teach him about time's relation to the world (as a fourth dimension), fate, and the nature of death. The Tralfamadorians are featured in several Vonnegut novels. In Slaughterhouse Five, they reveal that the universe will be accidentally destroyed by one of their test pilots, and there is nothing they can do about it.

- Montana Wildhack: A beautiful young model who is abducted and placed alongside Billy in the zoo on Tralfamadore. She and Billy develop an intimate relationship and they have a child. She apparently remains on Tralfamadore with the child after Billy is sent back to Earth. Billy sees her in a film showing in a pornographic book store when he stops to look at the Kilgore Trout novels sitting in the window. Her unexplained disappearance is featured on the covers of magazines sold in the store.

- "Wild Bob": A superannuated army officer Billy meets in the war. He tells his fellow POWs to call him "Wild Bob", as he thinks they are the 451st Infantry Regiment and under his command. He explains "If you're ever in Cody, Wyoming, ask for Wild Bob", which is a phrase that Billy repeats to himself throughout the novel. He dies of pneumonia.

- Eliot Rosewater: Billy befriends him in the veterans' hospital; he introduces Billy to the sci-fi novels of Kilgore Trout. Rosewater wrote the only fan letter Trout ever received. Rosewater had also suffered a terrible event during the war. Billy and Rosewater find the Trout novels helpful in dealing with the trauma of war. Rosewater is featured in other Vonnegut novels, such as God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965).

- Bertram Copeland Rumfoord: A Harvard history professor, retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general, and millionaire. He shares a hospital room with Billy and is interested in the Dresden bombing. He is in the hospital after breaking his leg on his honeymoon with his fifth wife Lily, a barely literate high school drop-out and go-go girl. He is described as similar in appearance and mannerisms to Theodore Roosevelt. Bertram is likely a relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, a character in Vonnegut's 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan.

- The Scouts: Two American infantry scouts trapped behind German lines who find Roland Weary and Billy. Roland refers to himself and the scouts as the "Three Musketeers". The scouts abandon Roland and Billy because the latter are slowing them down. They are revealed to have been shot and killed by Germans in ambush.

- Bernard V. O'Hare: The narrator's old war friend who was also held in Dresden and accompanies him there after the war. He is the husband of Mary O'Hare, and is a district attorney from Pennsylvania.

- Mary O'Hare: The wife of Bernard V. O'Hare, to whom Vonnegut promised to name the book The Children's Crusade. She is briefly discussed in the beginning of the book. When the narrator and Bernard try to recollect their war experiences Mary complains that they were just "babies" during the war and that the narrator will portray them as valorous men. The narrator befriends Mary by promising that he will portray them as she said and that in his book "there won't be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne."

- Werner Gluck: The sixteen-year-old German charged with guarding Billy and Edgar Derby when they are first placed at Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden. He does not know his way around and accidentally leads Billy and Edgar into a communal shower where some German refugee girls from Breslau are bathing. He is described as appearing similar to Billy, as they are distant cousins (a fact unknown to both of them).

Style

[edit]In keeping with Vonnegut's signature style, the novel's syntax and sentence structure are simple, and irony, sentimentality, black humor, and didacticism are prevalent throughout the work.[8] Like much of his oeuvre, Slaughterhouse-Five is broken into small pieces, and in this case, into brief experiences, each focused on a specific point in time. Vonnegut has noted that his books "are essentially mosaics made up of a whole bunch of tiny little chips...and each chip is a joke." Vonnegut also includes hand-drawn illustrations in Slaughterhouse-Five, and also in his next novel, Breakfast of Champions (1973). Characteristically, Vonnegut makes heavy use of repetition, frequently using the phrase, "So it goes". He uses it as a refrain when events of death, dying, and mortality occur or are mentioned; as a narrative transition to another subject; as a memento mori; as comic relief; and to explain the unexplained. The phrase appears 106 times.[9]

The book has been categorized as a postmodern, meta-fictional novel. The first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five is written in the style of an author's preface about how he came to write the novel. The narrator introduces the novel's genesis by telling of his connection to the Dresden bombing, and why he is recording it. He provides a description of himself and of the book, saying that it is a desperate attempt at creating a scholarly work. He ends the first chapter by discussing the beginning and end of the novel. He then segues to the story of Billy Pilgrim: "Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time", thus the transition from the writer's perspective to that of the third-person, omniscient narrator. (The use of "Listen" as an opening interjection has been said to mimic the opening "Hwaet!" of the medieval epic poem Beowulf.) The fictional "story" appears to begin in Chapter Two, although there is no reason to presume that the first chapter is not also fiction. This technique is common in postmodern meta-fiction.[10]

The narrator explains that Billy Pilgrim experiences his life discontinuously, so that he randomly lives (and re-lives) his birth, youth, old age and death, rather than experiencing them in the normal linear order. There are two main narrative threads: a description of Billy's World War II experience, which, though interrupted by episodes from other periods and places in his life, is mostly linear; and a description of his discontinuous pre-war and post-war lives. A main idea is that Billy's existential perspective had been compromised by his having witnessed Dresden's destruction (although he had come "unstuck in time" before arriving in Dresden).[11] Slaughterhouse-Five is told in short, declarative sentences, which create the impression that one is reading a factual report.[12]

The first sentence says, "All this happened, more or less." (In 2010, the line was ranked No. 38 on the American Book Review's list of "100 Best First Lines from Novels".)[13] The opening sentences of the novel have been said to contain the aesthetic "method statement" of the entire novel.[14]

Themes

[edit]War and death

[edit]In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut attempts to come to terms with war through the narrator's eyes, Billy Pilgrim. An example within the novel, showing Vonnegut's aim to accept his past war experiences, occurs in chapter one, when he states that "All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn't his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I've changed all the names."[15] As the novel continues, it is relevant that the reality is death.[16]

Slaughterhouse-Five focuses on human imagination while interrogating the novel's overall theme, which is the catastrophic impact that war leaves behind.[17] Death is something that happens fairly often in Slaughterhouse-Five. When a death occurs in the novel, Vonnegut marks the occasion with the saying "so it goes." Bergenholtz and Clark write about what Vonnegut actually means when he uses that saying: "Presumably, readers who have not embraced Tralfamadorian determinism will be both amused and disturbed by this indiscriminate use of 'So it goes.' Such humor is, of course, black humor."[18]

Religion and philosophy

[edit]Christian philosophy

[edit]Christian philosophy is present in Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, though not generally in a well-regarded manner. When God and Christianity is brought up in the work, it is often mentioned in a bitter or disregarding tone, particularly with regard to how the soldiers react to the mention of it. However, author JC Justus argues that Billy Pilgrim ultimately embraces something comparable to Christian morality in his acceptance of Tralfamadorian philosophy, referring to the "'Tralfamadorian determinism and passivity' that Pilgrim later adopts as well as Christian fatalism wherein God himself has ordained the atrocities of war...".[19] Following Justus's argument, Pilgrim was a character that had been through war and traveled through time. Having experienced all of these horrors in his lifetime, Pilgrim ended up adopting the Christian ideal that God had everything planned and he had given his approval for the war to happen.

Tralfamadorian philosophy

[edit]As Billy Pilgrim becomes "unstuck in time", he is faced with a new type of philosophy. Upon making acquaintance with the Tralfamadorians, he learns a different viewpoint concerning fate and free will. While Christianity may state that fate and free will are matters of God's divine choice and human interaction, Tralfamadorianism would disagree. According to Tralfamadorian philosophy, things are and always will be, and there is nothing that can change them. When Billy asks why they had chosen him, the Tralfamadorians reply, "Why you? Why us for that matter? Why anything? Because this moment simply is."[20] The mindset of the Tralfamadorian is not one in which free will exists. Things happen because they were always destined to be happening. The narrator of the story explains that the Tralfamadorians see time all at once. This concept of time is best explained by the Tralfamadorians themselves, as they speak to Billy Pilgrim on the matter stating, "I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is."[21] After this particular conversation on seeing time, Billy makes the statement that this philosophy does not seem to evoke any sense of free will. To this, the Tralfamadorian reply that free will is a concept that, out of the "visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe" and "studied reports on one hundred more," "only on Earth is there any talk of free will."[21]

Using the Tralfamadorian passivity of fate, Pilgrim learns to overlook death and the shock involved with death. He claims the Tralfamadorian philosophy on death to be his most important lesson:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. ... When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is "So it goes."[22]

Postmodernism

[edit]The significance of postmodernism is a reoccurring theme in Vonnegut's works. Postmodernism arose as a rejection of modernist narratives and structures. According to one critic, Tralfamadorianism is a restatement of Christian teleology: There is no purpose to life, effects do not have causes; the only reason for anything is that God has ordained it. This juxtaposition is displayed throughout the book, rather directly asking the reader to confront the logical absurdities inherent in both Christian faith and Tralfamadorianism. The rigid and dogmatic approach of Christianity is dismissed, while determinism is critiqued.[23]

Mental illness

[edit]Some have argued that Vonnegut is speaking out for veterans, many of whose post-war states are untreatable. Pilgrim's symptoms have been identified as what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder, which didn't exist as a term when the novel was written. In the words of one writer, "perhaps due to the fact that PTSD was not officially recognized as a mental disorder yet, the establishment fails Billy by neither providing an accurate diagnosis nor proposing any coping mechanisms."[24] Billy found life meaningless due to his experiences in the war, which desensitized and forever changed him.[25]

Symbols

[edit]Dresden

[edit]

Vonnegut was in the city of Dresden when it was bombed; he came home traumatized and unable to properly communicate the horror of what happened there. Slaughterhouse-Five is the product of the twenty years of work it took for him to articulate the experience in a way that satisfied him. William Allen says, "Precisely because the story was so hard to tell, and because Vonnegut was willing to take two decades necessary to tell it – to speak the unspeakable – Slaughterhouse-Five is a great novel, a masterpiece sure to remain a permanent part of American literature."[27]

Food

[edit]Billy Pilgrim ended up owning "half of three Tastee-Freeze stands. Tastee-Freeze was a sort of frozen custard. It gave all the pleasure that ice cream could give, without the stiffness and bitter coldness of ice cream" (61). Throughout Slaughterhouse-Five, when Billy is eating or near food, he thinks of food in positive terms. This is partly because food is both a status symbol and comforting to people in Billy's situation. "Food may provide nourishment, but its more important function is to soothe ... Finally, food also functions as a status symbol, a sign of wealth. For instance, en route to the German prisoner-of-war camp, Billy gets a glimpse of the guards' boxcar and is impressed by its contents ... In sharp contrast, the Americans' boxcar proclaims their dependent prisoner-of-war status."[18]

The Bird

[edit]Throughout the novel, the bird sings "Poo-tee-weet?" After the Dresden firebombing, the bird breaks out in song. The bird also sings outside of Billy's hospital window. The song has been interpreted as symbolizing a loss of words, or the inadequacy of words to describe traumatic situations.[28]

The Big Dog

[edit]During the course of the novel, there are references of a big dog barking. "The dog, who had sounded so ferocious in the winter distances, was a female German shepherd. She was shivering. Her tail was between her legs. She had been borrowed that morning from a farmer. She had never been to war before. She had no idea what game was being played. Her name was Princess." The dog serves as a recurring motif, described as sounding like a big bronze gong. In many cultures, gongs are used to signify an important event or as a rallying sound. Start of a battle, driving slaves, etc. The dog is thought to symbolize the numbing mechanization of warfare. It is also an ironic symbol, an innocent, scared, dog being used in warfare to herd POWs.

Allusions and references

[edit]Allusions to other works

[edit]As in other novels by Vonnegut, certain characters cross over from other stories, making cameo appearances and connecting the discrete novels to a greater opus. Fictional novelist Kilgore Trout, often an important character in other Vonnegut novels, is a social commentator and a friend to Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse-Five. In one case, he is the only non-optometrist at a party; therefore, he is the odd man out. He ridicules everything the Ideal American Family holds true, such as Heaven, Hell, and Sin. In Trout's opinion, people do not know if the things they do turn out to be good or bad, and if they turn out to be bad, they go to Hell, where "the burning never stops hurting." Other crossover characters are Eliot Rosewater, from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; Howard W. Campbell Jr., from Mother Night; and Bertram Copeland Rumfoord, relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, from The Sirens of Titan. While Vonnegut re-uses characters, the characters are frequently rebooted and do not necessarily maintain the same biographical details from appearance to appearance. Trout in particular is palpably a different person (although with distinct, consistent character traits) in each of his appearances in Vonnegut's work.[29]

In the Twayne's United States Authors series volume on Kurt Vonnegut, about the protagonist's name, Stanley Schatt says:

By naming the unheroic hero Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut contrasts John Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress" with Billy's story. As Wilfrid Sheed has pointed out, Billy's solution to the problems of the modern world is to "invent a heaven, out of 20th century materials, where Good Technology triumphs over Bad Technology. His scripture is Science Fiction, Man's last, good fantasy".[30]

The city in which the novel is set, Ilium, New York, is another allusion. This city appears in many of his books.

Cultural and historical allusions

[edit]Slaughterhouse-Five makes numerous cultural, historical, geographical, and philosophical allusions. It tells of the bombing of Dresden in World War II, and refers to the Battle of the Bulge, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights protests in American cities during the 1960s. Billy's wife, Valencia, has a "Reagan for President!" bumper sticker on her Cadillac, referring to Ronald Reagan's failed 1968 Republican presidential nomination campaign. Another bumper sticker is mentioned, reading "Impeach Earl Warren," referencing a real-life campaign by the far-right John Birch Society.[31][32][33]

The Serenity Prayer appears twice.[34] Critic Tony Tanner suggested that it is employed to illustrate the contrast between Billy Pilgrim's and the Tralfamadorians' views of fatalism.[35] Richard Hinchcliffe contends that Billy Pilgrim could be seen at first as typifying the Protestant work ethic, but he ultimately converts to evangelicalism.[36]

Vonnegut's own experiences

[edit]In 1995, Vonnegut said that Billy Pilgrim was modeled on Edward "Joe" Crone, a thin soldier who died in Dresden. Vonnegut had told this to friends earlier, but waited until after he learned that both of Crone's parents were deceased to publicly disclose this information.[37][38]

Edgar Derby, killed for looting a teapot, was modeled on Vonnegut's fellow prisoner Mike Palaia, who was executed for plundering a jar of food (variously described as beans, fruit, or cherries).[39][40]

Reception

[edit]The reviews of Slaughterhouse-Five have been largely positive since the March 31, 1969 review in the New York Times stated: "you'll either love it, or push it back in the science-fiction corner."[41] It was Vonnegut's first novel to become a bestseller, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for sixteen weeks and peaking at No. 4.[42] In 1970, Slaughterhouse-Five was nominated for best-novel Nebula and Hugo Awards. It lost both to The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. It has since been widely regarded as a classic anti-war novel, and has appeared in Time magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.[43]

Censorship controversy

[edit]Slaughterhouse-Five has been the subject of many attempts at censorship due to its irreverent tone, purportedly obscene content and depictions of sex, American soldiers' use of profanity, and perceived heresy. It was one of the first literary acknowledgments that homosexual men, referred to in the novel as "fairies", were among the victims of the Holocaust.[44]

In the United States it has at times been banned from literature classes, removed from school libraries, and struck from literary curricula.[45] In 1972, following the ruling of Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, it was banned from Rochester Community Schools in Oakland County, Michigan.[46] The circuit judge described the book as "depraved, immoral, psychotic, vulgar and anti-Christian."[44] It was later reinstated.[47]

In 1973, Vonnegut learned of a school district in North Dakota that was antagonistic towards Slaughterhouse-Five. An English teacher at a high school in the district wanted to read the novel with their class. Charles McCarthy, the head of the school board, declared the novel inappropriate because of obscene language. All copies of Vonnegut's novel in the school were burned in a furnace.[48]

In a letter to McCarthy in 1973, Vonnegut defended his credibility, his character, and his work. In the letter, titled "I Am Very Real", Vonnegut wrote that his books "beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are". He contended that his work should not be censored based on the general message in the novel.[49][48]

The U.S. Supreme Court considered the First Amendment implications of the removal of the book, among others, from public school libraries in the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) and concluded that "local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to 'prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.'" Slaughterhouse-Five is the sixty-seventh entry to the American Library Association's list of the "Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999" and number forty-six on the ALA's "Most Frequently Challenged Books of 2000–2009".[45] In August 2011, the novel was banned at the Republic High School in Missouri. The Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library countered by offering 150 free copies of the novel to Republic High School students on a first-come, first-served basis.[50]

In an effort to comply with a new 2024 Tennessee state law which added to the 2022 Age Appropriate Materials Act, Slaughterhouse-Five was banned - along with nearly 400 other titles - at the discretion of middle and high school librarians serving Wilson County Schools, a public school district in the greater metropolitan Nashville area.[51][52][53] It has also been recently banned from school libraries in the state of Florida.[54]

In 2024 the book was banned in Texas by the Katy Independent School District on the basis that the novel is "adopting, supporting, or promoting gender fluidity"[55] despite also pronouncing a bullying policy that protects infringements on the rights of the student.[56]

Criticism

[edit]On the book's philosophy

[edit]Slaughterhouse-Five has been described as a quietist work, because Billy Pilgrim believes that the notion of free will is a quaint Earthling illusion.[57] According to Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, "Vonnegut's critics seem to think that he is saying the same thing [as the Tralfamadorians]." For Anthony Burgess, "Slaughterhouse is a kind of evasion—in a sense, like J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan—in which we're being told to carry the horror of the Dresden bombing, and everything it implies, up to a level of fantasy..." For Charles Harris, "The main idea emerging from Slaughterhouse-Five seems to be that the proper response to life is one of resigned acceptance." For Alfred Kazin, "Vonnegut deprecates any attempt to see tragedy, that day, in Dresden...He likes to say, with arch fatalism, citing one horror after another, 'So it goes.'" For Tanner, "Vonnegut has...total sympathy with such quietistic impulses." The same notion is found throughout The Vonnegut Statement, a book of original essays written and collected by Vonnegut's most loyal academic fans.[57] When confronted with the question of how the desire to improve the world fits with the notion of time presented in Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut responded "you understand, of course, that everything I say is horseshit."[58]

Historical inaccuracy

[edit]For certain elements of historical research, Vonnegut used (and quoted) The Destruction of Dresden, a book published in 1963 by British author David Irving. Irving was later denounced and discredited for being a Holocaust denier and a Nazi sympathizer.[59][60][61] In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut quotes and bases claims on Irving's book, most notably that 135,000 people were killed in the bombing of Dresden.[62][63] New, evidence-based research has found that Irving's claims are inaccurate, and the number of deaths in the Dresden bombing was fewer than 25,000.[64][65][66][67][68] George Packer, in an essay published in The New Yorker, claimed that "For many readers of Irving and Vonnegut, the bombing of Dresden scrambled the order of perpetrators and victims in the Second World War and came close to establishing a moral equivalence", referring to the exaggeration that "reached the West through 'The Destruction of Dresden', a 1963 best-seller by David Irving".[69]

Both before and for years after Vonnegut's book was initially published, the figure of 135,000 was used even by American officials, including U.S Air Force general Ira C. Eaker, who was quoted in Slaughterhouse-Five. Later editions of Slaughterhouse-Five have not featured any kind of explanatory note about, or correction to, this figure.[70]

Adaptations

[edit]- A film adaptation of the book was released in 1972. Although critically praised, the film was a box office flop. It won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a Hugo Award and Saturn Award. Vonnegut commended the film greatly. In 2013, Guillermo del Toro announced his intention to remake the 1972 film and work with a script by Charlie Kaufman.[71]

- In 1989, a theatrical adaptation was performed at the Everyman Theatre, in Liverpool, England.[72]

- In 1996, another theatrical adaptation of the novel premiered at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago. The adaptation was written and directed by Eric Simonson and featured actors Rick Snyder, Robert Breuler and Deanna Dunagan.[73] The play has subsequently been performed in several other theaters, including a New York premiere production in January 2008, by the Godlight Theatre Company. An operatic adaptation by Hans-Jürgen von Bose premiered in July 1996 at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, Germany. Billy Pilgrim II was sung by Uwe Schonbeck.[74]

- In September 2009, BBC Radio 3 broadcast a feature-length radio drama based on the book, which was dramatised by Dave Sheasby, featured Andrew Scott as Billy Pilgrim and was scored by the group 65daysofstatic.[75]

- In September 2020, a graphic novel adaptation of the book, written by Ryan North and drawn by Albert Monteys, was published by BOOM! Studios, through their Archaia Entertainment imprint. It was the first time the book has been adapted into the comics medium.[76]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Strodder, Chris (2007). The Encyclopedia of Sixties Cool. Santa Monica Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781595809865.

- ^ "Publication: Slaughterhouse Five". www.isfdb.org.

- ^ a b Powers, Kevin, "The Moral Clarity of ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ at 50", The New York Times, March 23, 2019, Sunday Book Review, p. 13.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. 2009 Dial Press Trade paperback edition, 2009, p. 1

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. 2009 Dial Press Trade paperback edition, 2009, p. 43

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (January 12, 1999). Slaughterhouse-Five. Dial Press Trade Paperback. pp. 160. ISBN 978-0-385-33384-9.

- ^ "Slaughterhouse Five". Letters of Note. November 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ Westbrook, Perry D. "Kurt Vonnegut Jr.: Overview." Contemporary Novelists. Susan Windisch Brown. 6th ed. New York: St. James Press, 1996.

- ^ "Slaughterhouse Five full text" (PDF). antilogicalism.com/. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Waugh, Patricia. Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1988. p. 22.

- ^ He first time-travels while escaping from the Germans in the Ardennes forest. Exhausted, he falls asleep against a tree and experiences events from his future life.

- ^ "Kurt Vonnegut's Fantastic Faces". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ "100 Best First Lines from Novels". American Book Review. The University of Houston-Victoria. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022.

- ^ Jensen, Mikkel (March 20, 2016). "Janus-Headed Postmodernism: The Opening Lines of SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE". The Explicator. 74 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1080/00144940.2015.1133546. S2CID 162509316.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (1991). SlaughterHouse-Five. New York: Dell Publishing. p. 1.

- ^ McGinnis, Wayne (1975). "The Arbitrary Cycle of Slaughterhouse-Five: A Relation of Form to Theme". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 17 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/00111619.1975.10690101.

- ^ McGinnis, Wayne (1975). "The Arbitrary Cycle of Slaughterhouse-Five: A Relation of Form to Theme". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 17 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/00111619.1975.10690101.

- ^ a b Bergenholtz, Rita; Clark, John R. (1998). "Food for Thought in Slaughterhouse-Five". Thalia. 18 (1): 84–93. ProQuest 214861343. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Justus, JC (2016). "About Edgar Derby: Trauma and Grief in the Unpublished Drafts of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 57 (5): 542–551. doi:10.1080/00111619.2016.1138445. S2CID 163412693. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 73. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ^ a b Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 82. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children's Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ^ Vanderwerken, L. David. "Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five at Forty". CORE.

- ^ Czajkowska, Aleksandra (2021). ""To give form to what cannot be comprehended": Trauma in Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five and Martin Amis's Time's Arrow" (PDF). Crossroads: A Journal of English Studies. 3 (34): 59–72. doi:10.15290/CR.2021.34.3.05. S2CID 247257373 – via The Repository of the University of Białystok.

- ^ Brown, Kevin (2011). ""The Psychiatrists Were Right: Anomic Alienation in Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five"". South Central Review. 28 (2): 101–109. doi:10.1353/scr.2011.0022. S2CID 170085340.

- ^ Armitstead, Claire (July 15, 2022). "From Curb to Kurt: Larry David's director on how his literary hero helped him through personal pain". The Guardian.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2009). Bloom's Modern Interpretations: Kurt Vonnegut's of Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 3–15. ISBN 9781604135855. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Holdefer, Charles (2017). ""Poo-tee-weet?" and Other Pastoral Questions". E-Rea. 14 (2). doi:10.4000/erea.5706.

- ^ Lerate de Castro, Jesús (November 30, 1994). "The narrative function of Kilgore Trout and his fictional works in Slaughterhouse-Five". Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses (7): 115–122. doi:10.14198/RAEI.1994.7.09. hdl:10045/6044. S2CID 32180954.

- ^ Stanley Schatt, "Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Chapter 4: Vonnegut's Dresden Novel: Slaughterhouse-Five.", In Twayne's United States Authors Series Online. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1999 Previously published in print in 1976 by Twayne Publishers.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (November 3, 1991). Slaughterhouse-Five. Dell Fiction. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-440-18029-6.

- ^ Andrew Glass (December 9, 2017). "John Birch Society founded, Dec. 9, 1958". POLITICO. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Becker, Bill (April 13, 1961). "WELCH, ON COAST, ATTACKS WARREN; John Birch Society Founder Outlines His Opposition to the Chief Justice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Susan Farrell; Critical Companion to Kurt Vonnegut: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work, Facts On File, 2008, Page 470.

- ^ Tanner, Tony. 1971. "The Uncertain Messenger: A Study of the Novels of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.", City of Words: American Fiction 1950-1970 (New York: Harper & Row), pp. 297-315.

- ^ Hinchcliffe, Richard (2002). ""Would'st thou be in a dream: John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five"". European Journal of American Culture. 20 (3): 183–196(14). doi:10.1386/ejac.20.3.183.

- ^ dkramer3@naz.edu (March 8, 2019). "Kurt Vonnegut's 1995 "Billy Pilgrim" pilgrimage to the Mt. Hope grave of Edward R. Crone Jr, Brighton High School '41". Talker of the Town. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "23 April (1989): Kurt Vonnegut to George Strong | The American Reader". theamericanreader.com. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Szpek, Ervin E.; Idzikowski, Frank J. (2008). Shadows of Slaughterhouse Five: Reflections and Recollections of the American Ex-POWs of Schlachthof Fünf, Dresden, Germany. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4401-0567-8.

- ^ "PALAIA MICHAEL D | The American Overseas Memorial Day Association". aomda.org. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ "Books of The Times: At Last, Kurt Vonnegut's Famous Dresden Book". New York Times. March 31, 1969. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ^ Justice, Keith (1998). Bestseller Index: all books, by author, on the lists of Publishers weekly and the New York times through 1990. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. pp. 316. ISBN 978-0786404223.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (January 6, 2010). "All-TIME 100 Novels: How We Picked the List". Time.

- ^ a b Morais, Betsy (August 12, 2011). "The Neverending Campaign to Ban 'Slaughterhouse Five'". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Admin (March 27, 2013). "100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999". Banned & Challenged Books. American Library Association. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ "Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, 200 NW 2d 90 - Mich: Court of Appeals 1972". Archived from the original on March 25, 2019.

- ^ "History of the Freedom to Read Foundation, 1969-2009". Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Vonnegut, Kurt. "I Am Very Real." Received by Charles McCarthy, 16 November 1973

- ^ Hibbard, Laura (March 30, 2012). "Kurt Vonnegut's Letter To Drake High School: 'You Have Insulted Me'". HuffPost. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ Flagg, Gordon (August 9, 2011). "Vonnegut Library Fights Slaughterhouse-Five Ban with Giveaways". American Libraries. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ Beyeler, Kelsey (October 25, 2024). "Roughly 400 Books Removed From Wilson County School Libraries". Nashville Scene. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Beyeler, Kelsey (April 25, 2024). "Banned Together: How Book Censorship Is Affecting Tennessee". Nashville Scene. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Cavendish, Steve (October 25, 2024). "Here Are the Nearly 400 Books Wilson County Has Banned From Its Schools". Nashville Banner. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Marcos, Coral Murphy (November 13, 2024). "Florida officials report hundreds of books removed from schools". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ "Instructional Resources Information / Home".

- ^ "Bullying Prevention and Student Support / Home".

- ^ a b Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five: The Requirements of Chaos, in Studies in American Fiction, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring, 1978, p 67.

- ^ Admin (October 4, 2016). "KURT VONNEGUT: PLAYBOY INTERVIEW (1973)". Scraps from the loft. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Dodd, Vikram (April 12, 2000). "Irving: consigned to history as a racist liar". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (2002). Telling Lies about Hitler: The Holocaust, History and the David Irving Trial. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-417-5.

- ^ Thal, Ian (March 29, 2012). "The Journals of Ian Thal: Slaughterhouse Five and Being Duped About Dresden". The Journals of Ian Thal. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ "Repeating Nazi Propaganda, From Kurt Vonnegut to NPR". The Forward. August 10, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ Roston, Tom (November 11, 2021). "What Early Drafts of 'Slaughterhouse-Five' Reveal About Kurt Vonnegut's Struggles". TIME. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ Taylor, Frederick (October 2, 2008). "Death Toll Debate: How Many Died in the Bombing of Dresden?". Der Spiegel. ISSN 2195-1349. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ "Firebombing (Published 2004)". May 2, 2004. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ "Researchers revise toll in Dresden bomb raids (Published 2008)". October 2, 2008. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ "Fact check: Myths about Dresden 1945 victim numbers debunked 02/13/2025". DW. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ Kamm, Oliver (April 14, 2007). "Catastrophic visions forged in Dresden". www.thetimes.com. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- ^ Packer, George (January 24, 2010). "Embers". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved August 19, 2025.

- ^ Roston, Tom (November 11, 2021). "What Early Drafts of 'Slaughterhouse-Five' Reveal About Kurt Vonnegut's Struggles". TIME. Retrieved August 19, 2025.

- ^ Sanjiv, Bhattacharya (July 10, 2013). "Guillermo del Toro: 'I want to make Slaughterhouse Five with Charlie Kaufman '". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ "The Everyman Theatre Archive: Programmes". Liverpool John Moores University. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Slaughterhouse-Five: September 18 - November 10, 1996". Steppenwolf Theatre Company. 1996. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Couling, Della (July 19, 1996). "Pilgrim's progress through space". The Independent on Sunday.

- ^ Sheasby, Dave (September 20, 2009). "Slaughterhouse 5". BBC Radio 3.

- ^ Reid, Calvin (January 8, 2020). "Boom! Plans 'Slaughterhouse-Five' Graphic Novel in 2020". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

External links

[edit] Media related to Slaughterhouse-Five at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Slaughterhouse-Five at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Slaughterhouse-Five at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Slaughterhouse-Five at Wikiquote- Official website

- Kurt Vonnegut discusses Slaughterhouse-Five on the BBC World Book Club

- Kilgore Trout Collection

- Photos of the first edition of Slaughterhouse-Five

- Visiting Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden

- Slaughterhous Five – Pictures of the area 65 years later

- Slaughterhouse Five digital theatre play

Slaughterhouse-Five

View on GrokipediaPublication and Authorial Context

Writing and Publication History

Kurt Vonnegut, captured as a U.S. Army prisoner of war during the February 1945 Allied firebombing of Dresden, struggled for over two decades to write a book addressing the experience, which he referred to as his "Dresden book."[2][6] Despite this delay, Vonnegut published five earlier novels, beginning with Player Piano in 1952, while intermittently attempting non-linear and experimental approaches to the Dresden material without success.[2] A 1967 research trip to Dresden, arranged through personal connections amid Cold War restrictions, provided crucial details and renewed momentum, allowing Vonnegut to complete the manuscript in under a year thereafter.[7] He submitted the final draft on June 10, 1968, marking the culmination of a process that had spanned more than 20 years from the event itself.[7] Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death was published in hardcover by Delacorte Press on March 31, 1969, comprising 186 pages priced at $5.95.[8][9] The project received a $25,000 advance from publisher Seymour Lawrence, who had been impressed by Vonnegut's contemporaneous book reviews during a period of fiction-writing hiatus.[10] This edition marked Vonnegut's sixth novel and his first major commercial success.[2]Kurt Vonnegut's Relevant Biography

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was born on November 11, 1922, in Indianapolis, Indiana, into a family of German descent prominent in the city's brewing and architectural trades.[11] His father, Kurt Vonnegut Sr., was an architect whose business declined during the Great Depression, while his mother, Edith Lieber Vonnegut, came from a family involved in brewing before Prohibition.[11] Vonnegut attended Shortridge High School, where he wrote for the student newspaper The Echo, fostering an early interest in journalism.[11] He later enrolled at Cornell University in 1940, studying chemistry and biology while serving as managing editor of the Daily Sun.[11] In November 1942, amid World War II, Vonnegut enlisted in the U.S. Army, undergoing training before deployment to Europe in 1944 as an infantry scout with the 106th Infantry Division.[2] During the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, he was captured by German forces and imprisoned at Stalag IV-B near Mühlberg.[2] In January 1945, he was transferred with a labor detachment to Dresden, where he worked in a malt syrup factory; on the night of February 13–15, 1945, Allied firebombing devastated the city, but Vonnegut survived by sheltering in an underground meat locker beneath Slaughterhouse-Five.[2] These events profoundly shaped his worldview, providing the autobiographical core for his later novel, as he later described struggling for over two decades to articulate the trauma.[12] Following his discharge in 1945, Vonnegut briefly studied anthropology at the University of Chicago while working as a police reporter.[11] He then took a position in public relations at General Electric in Schenectady, New York, from 1947 to 1951, an experience that influenced his satirical views on technology and industry.[11] During this period, he began publishing short stories and released his debut novel, Player Piano, in 1952, marking the start of a writing career that culminated in Slaughterhouse-Five's publication on March 31, 1969, by Delacorte Press.[2] The novel drew directly from his Dresden ordeal, blending it with science fiction elements to critique war's absurdity.[2]Influences from Vonnegut's Life

Kurt Vonnegut's experiences as a prisoner of war during World War II profoundly shaped Slaughterhouse-Five, particularly the novel's depiction of the Allied firebombing of Dresden. Captured by German forces on December 19, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, Vonnegut was among American infantrymen marched to Dresden, where he and fellow prisoners were housed in Schlachthof Fünf, an underground slaughterhouse used as a meat-storage facility.[2] From February 13 to 15, 1945, British and American bombers unleashed over 3,900 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the city, creating a firestorm that killed an estimated 25,000 civilians and reduced much of Dresden to rubble.[12] Vonnegut survived the inferno by sheltering in the slaughterhouse's meat locker, emerging afterward to witness the devastation and participate in body recovery efforts amid the charred remains.[2] These events form the semi-autobiographical core of the novel's war narrative, with protagonist Billy Pilgrim's captivity and survival mirroring Vonnegut's own. Vonnegut labored for 23 years to articulate the trauma, initially struggling with its incomprehensibility upon returning home, where he found himself unable to convey the horror's scale to family and friends.[12] The fragmented, non-linear structure of Billy's "unstuck in time" experiences reflects Vonnegut's fragmented memories and the psychological disorientation induced by the bombing, akin to symptoms of what later became recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder.[13] Vonnegut inserts himself as a minor character in the story, underscoring the personal stake in recounting these events, and draws on his postwar visits to Dresden for research, including interactions with former guards and locals to verify details.[2] Additional personal losses influenced the novel's themes of mortality and absurdity. While on leave in May 1944, Vonnegut learned of his mother Edith's suicide by overdose on Mother's Day, an event that haunted him and parallels the detached treatment of death in Billy's life, marked by the refrain "So it goes."[14] Vonnegut's sister Alice died of cancer in 1958 shortly after her husband perished in a railway accident, leaving orphaned nephews whom Vonnegut helped raise; this echoes Billy's family disruptions and the novel's portrayal of sudden, meaningless loss.[14] These biographical elements underscore the book's causal link between lived trauma and its literary expression, prioritizing raw experience over sanitized narratives of war.[13]Narrative Elements

Plot Summary

Slaughterhouse-Five, subtitled The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, recounts the life of Billy Pilgrim, a World War II veteran who becomes "unstuck in time," experiencing his existence nonlinearly without control over the sequence.[15][16] The narrative opens with Kurt Vonnegut, the author and a Dresden survivor as a POW, describing his postwar return to the city with a friend and his decades-long struggle to compose an antiwar book about the 1945 firebombing that killed approximately 25,000 civilians.[16][17] Billy, an indifferent soldier and former optometry student serving as a chaplain's assistant, is captured by German forces during the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 and transported by boxcar to a POW camp before reassignment to Dresden.[15][17] Housed in the city's Slaughterhouse-Five, a former meat-processing facility used as a refuge, Billy and fellow prisoners emerge after the February 13–15, 1945, Allied bombing to a devastated landscape of rubble and charred bodies, which they exhume for mass burial in five truckloads of corpses.[15][16] Postwar, Billy settles in Ilium, New York, practices optometry, marries Valencia Merble—the daughter of his boss—fathers a son and daughter, and in 1968 survives a plane crash that kills the pilot and leaves him hospitalized; Valencia dies en route to visit him after dying from carbon monoxide poisoning in her car.[15][17] Billy claims abduction by extraterrestrial Tralfamadorians from the planet Tralfamadore, who exhibit him in a zoo alongside actress Montana Wildhack, with whom he mates, while instructing him that all moments in time exist simultaneously, rendering death and free will illusions—"so it goes" punctuates every death in the text.[16][15] Other episodes include Billy's brief affair revealed via a science fiction novel by Kilgore Trout, a Vietnam War-era radio address where he endorses Tralfamadorian fatalism, and fragmented memories of his unglamorous infantry service, including the accidental death of his friend Kurt alongside a latrine.[17][15] The novel's structure intersperses these events with Vonnegut's authorial intrusions, bird's-eye views of the bombing, and recurring motifs like the color teal and the phrase "Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time," emphasizing war's absurdity and human fragility.[16][18]Principal Characters

Billy Pilgrim functions as the novel's protagonist, portrayed as a frail, passive World War II chaplain's assistant who becomes "unstuck in time," involuntarily reliving moments from his life in non-linear order.[19] An optometrist from Ilium, New York, by trade, Pilgrim survives the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war and later claims abduction by the alien Tralfamadorians, who teach him their philosophy of perceiving all time simultaneously.[20] His character embodies anti-heroic traits, marked by physical awkwardness, emotional detachment, and acceptance of fate rather than resistance to war's absurdities.[21] The narrator, identified as Kurt Vonnegut himself, appears as a semi-autobiographical figure who recounts his own experiences as a Dresden POW alongside Pilgrim's story, framing the narrative with personal reflections on writing the book.[22] Vonnegut inserts himself to highlight the challenges of depicting trauma, mentioning failed attempts to research the war with friend Bernard V. O'Hare before conceiving the novel.[21] Roland Weary emerges as a boastful, aggressive American soldier who befriends and then blames Pilgrim for their capture by German forces during the Battle of the Bulge.[21] Obsessed with war fantasies and self-aggrandizing tales of the "Three Musketeers," Weary dies of gangrene and, on his deathbed, entrusts revenge against Pilgrim to Paul Lazzaro.[23] Paul Lazzaro represents a vengeful, criminal-minded POW known for his capacity for hatred, swearing to kill Pilgrim for Weary's death and later succeeding in Pilgrim's future timeline.[23] A small, wiry figure with a history of violence, Lazzaro embodies unchecked malice amid the POWs' hardships.[24] Edgar Derby, a forty-year-old high school teacher drafted into service, stands out among POWs for his dignity and execution by firing squad for looting a teapot from Dresden's ruins, underscoring the novel's irony of meaningless death.[24] Predicted early as the "one who would die" yet hailed as a hero by the Tralfamadorians for his moral stance against book-burning.[25] The Tralfamadorians appear as tentacled, green extraterrestrials from the planet Tralfamadore, who abduct Pilgrim and exhibit him in a zoo, imparting their deterministic view that all moments exist eternally, thus negating free will or regret.[19] Bernard V. O'Hare serves as Vonnegut's real-life comrade from the 106th Infantry Division, referenced in the narrator's research struggles and symbolizing the difficulty in articulating war's futility.[21]Structure and Style

The narrative structure of Slaughterhouse-Five employs a non-linear chronology, with protagonist Billy Pilgrim described as "unstuck in time," experiencing episodes from his life in random, disjointed sequence rather than linear progression. This fragmentation reflects the Tralfamadorian aliens' view that time is a static totality where all moments coexist eternally, rendering free will illusory and events inevitable. [26] [27] The novel's ten chapters alternate between Billy's temporal jumps—spanning his World War II captivity, the Dresden bombing, postwar optometry practice, and abduction to Tralfamadore—creating an episodic, mosaic-like form that eschews traditional plot arcs for associative leaps. [28] Framing chapters one and ten feature Vonnegut's meta-narrative intrusions, where he recounts his own Dresden survivor interviews and writing difficulties, blurring autobiography with fiction to underscore the inadequacy of linear storytelling for conveying trauma. [29] Stylistically, Vonnegut adopts a terse, colloquial prose marked by irony and understatement, juxtaposing mundane details against atrocities to evoke absurd detachment; for instance, horrific deaths are followed by the refrain "So it goes," repeated 106 times to signal fatalistic acceptance of mortality across all timelines. [30] This repetition functions as a rhythmic device, echoing Tralfamadorian quietism while critiquing human attempts to impose meaning on chaos, and contrasts the novel's satirical sci-fi elements—like Billy's zoo captivity on Tralfamadore—with raw war realism drawn from Vonnegut's experiences. [31] The style incorporates postmodern collage techniques, parodying genres such as pulp science fiction and war heroism through abrupt shifts, lists (e.g., Billy's war souvenirs), and direct authorial addresses that break the fourth wall, fostering a tone of wry resignation over sensationalism. [32] Such elements prioritize emotional simultaneity over sequential causality, aligning form with the novel's philosophical rejection of progressive narratives. [33]Thematic Analysis

Portrayal of War

In Slaughterhouse-Five, war is depicted as an absurd, chaotic force that strips individuals of agency and meaning, rather than a heroic or purposeful endeavor. The protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, an unwilling and inept American soldier during World War II, embodies this through his passive role as a chaplain's assistant who is captured early in the Battle of the Bulge on December 19, 1944, and subsequently endures the tedium of POW camps before the Dresden firebombing. His experiences underscore war's bureaucratic banality and randomness, with soldiers portrayed as children or incompetents—Vonnegut subtitles the novel "The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death"—highlighting the futility of sending unprepared youths into mechanized slaughter.[34] [35] The Dresden bombing on February 13–15, 1945, serves as the novel's central emblem of war's indiscriminate horror, transforming a culturally rich city—likened to "the Florence of the Elbe"—into a lunar wasteland of ash and corpses, where Allied bombers drop 3,900 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs, incinerating an estimated 25,000 civilians and refugees.[2] Billy and fellow POWs survive only due to their internment in an underground slaughterhouse meat locker, emerging to a scene of grotesque desolation where they are forced into corpse-mining details, handling bodies softened by fire into a "syrupy" state treated with malt syrup to prevent dissolution.[36] This survival, amid the deaths of Valencia Merble's father and others, is met with the refrain "So it goes," repeated over 100 times in the text to mark every death from trivial accidents to mass annihilation, diminishing war's gravity into resigned inevitability without glorification or moralizing.[37] Vonnegut's non-linear structure, interspersing war's traumas with Billy's postwar life and alien abduction fantasies, mirrors the psychological fragmentation of combat survivors, portraying war not as a linear narrative of victory but as an enduring, inescapable disruption of time and sanity.[13] This technique critiques the absurdity of military rationales, as seen in the execution of Edgar Derby for scavenging a teapot amid the ruins— a minor theft punished by firing squad—exemplifying how war amplifies petty hierarchies into lethal farce.[38] While drawing from Vonnegut's own POW witnessing of Dresden, the novel rejects didactic anti-war preaching, instead using deadpan humor and science-fiction to expose violence's pointlessness, influencing its reception amid the Vietnam War era as a indictment of endless conflict.[39] [40]Free Will Versus Determinism

In Slaughterhouse-Five, the tension between free will and determinism manifests through the Tralfamadorian aliens' philosophy, which posits that time exists simultaneously in four dimensions, rendering all events fixed and inevitable from the universe's origin.[41] Tralfamadorians perceive past, present, and future as unchangeable "bugs" in the eternal structure of spacetime, advising acceptance rather than resistance, as encapsulated in their refrain "so it goes" for every death or tragedy.[42] This deterministic framework explicitly rejects free will, with Tralfamadorians informing Billy Pilgrim that "only on Earth is there any talk of free will" and that humans merely execute predetermined biochemical impulses without agency.[43] Billy Pilgrim, the protagonist, internalizes this worldview after his abduction, becoming "unstuck in time" and experiencing his life non-chronologically, which fosters a fatalistic detachment from suffering, including the Dresden bombing and his own impending assassination.[44] Under Tralfamadorian influence, Billy concludes that efforts to alter outcomes are illusory, as "among the things Billy Pilgrim could not change were the past, the present, and the future," leading him to passively endure traumas like his World War II captivity and postwar existential voids.[43] This adoption aligns with predestination, where human actions are scripted ab initio, stripping individuals of moral responsibility for events like wartime atrocities.[41] Yet Vonnegut undercuts pure determinism through narrative irony and the novel's anti-war imperative, suggesting that wholesale acceptance of fatalism enables quietism amid preventable horrors.[45] Billy's fragmented timeline, while echoing Tralfamadorian eternity, highlights human vulnerability to chance—such as his father's pool ordeal or the plane crash—implying that perceived determinism may rationalize trauma rather than reveal cosmic truth. Critics note this as an "irreconcilable conflict," where the Tralfamadorian lens copes with Dresden's 1945 firebombing's 25,000 civilian deaths but clashes with Vonnegut's insistence on bearing witness to urge agency against repetition.[47][48] Ultimately, the theme probes determinism's allure for the powerless while affirming free will's necessity for ethical action, as unchecked predestination risks excusing systemic violence.Time, Memory, and Human Experience

Billy Pilgrim, the novel's protagonist, becomes "unstuck in time," involuntarily traversing moments of his life in a non-chronological sequence, from his World War II captivity to postwar domesticity and abduction by extraterrestrial Tralfamadorians.[50] This fragmented temporality disrupts conventional narrative progression, emphasizing how severe trauma fractures linear recollection into intrusive, disjointed episodes.[13] Scholars interpret this as a literary depiction of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, where survivors relive horrors through vivid, uncontrolled flashbacks rather than sequential memory.[51] Vonnegut himself delayed writing the novel for over 20 years after witnessing the Allied firebombing of Dresden in February 1945, indicating that such temporal disorientation stems from the psyche's resistance to processing overwhelming violence.[52] The author's meta-narrative intrusions further blur time's boundaries, as Vonnegut reflects on his stalled efforts to recount the Dresden slaughterhouse ordeal, where he and Billy-like prisoners sheltered amid the ruins.[53] This non-linearity underscores memory's unreliability in human experience: events are not stored as orderly archives but as persistent, involuntary eruptions that defy volitional control or erasure.[54] In contrast to empirical causality—where actions precede consequences in predictable chains—the novel posits time as a static continuum, accessible only piecemeal through mnemonic triggers like explosions or loss.[55] Yet, this portrayal critiques passive acceptance; Billy's passive witnessing of his own death and others' fates highlights the human drive to seek agency amid apparent predestination, revealing memory as both tormentor and preserver of individual agency.[50] Tralfamadorian philosophy, encountered in Billy's visions, views all temporal instants as eternally fixed—"like beads on a string"—rendering change illusory and suffering inevitable, encapsulated in the refrain "so it goes" after each death.[56] For humans, however, this four-dimensional perspective clashes with experiential reality: memory imposes a subjective linearity, forcing confrontation with irreversible losses such as the Dresden inferno's estimated 25,000 civilian fatalities, which Vonnegut survived but could not linearly narrate without distortion.[13] The tension illustrates a core human predicament—bounded by sequential perception, individuals grapple with memories that affirm causality's weight, fostering resilience through retrospective meaning-making rather than alien detachment.[57] Thus, Vonnegut employs temporal dislocation not merely as stylistic innovation but as a realist probe into how war erodes temporal coherence, compelling survivors to reconstruct fractured lives from mnemonic shards.[51]Philosophical Elements

Tralfamadorian Philosophy

In Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, the Tralfamadorians, an alien species from the planet Tralfamadore, perceive time not as a linear progression but as a static four-dimensional landscape where all moments—past, present, and future—exist simultaneously and eternally.[42][44] This view renders time-travel illusory, as individuals like protagonist Billy Pilgrim become "unstuck in time" by jumping between fixed moments rather than altering a flowing sequence.[41] The Tralfamadorians liken human life to a "stretch of the Rocky Mountains," with each moment a permanent peak or valley unchangeable by will or effort.[58] Central to Tralfamadorian doctrine is the rejection of free will, which they dismiss as an Earthling delusion confined to human psychology.[59] They assert that all events are predetermined by the unchanging structure of spacetime, encapsulated in their phrase "And so on," indicating inevitability without purpose or agency—"If you know this," one Tralfamadorian tells Billy, "you can ignore the awful stuff."[44][58] This fatalism extends to interstellar disasters, such as the accidental destruction of their own planet by a test pilot pressing a button in a fixed moment, which they accept without intervention because "he has always pressed it" and "he will always press it."[41] Regarding death and suffering, Tralfamadorians maintain that mortality is merely a temporary "bad condition" in an individual's eternal timeline, as the deceased remain vividly alive in prior moments.[60] They teach Billy the refrain "So it goes," uttered after every death in the novel to signify stoic acceptance rather than grief, equating all fatalities—whether from war, accident, or age—as structurally equivalent and unalterable.[26] This perspective fosters a form of quietism, focusing attention on pleasant instants while disregarding horrors, as the Tralfamadorians advise Billy to "ignore the awful stuff" amid their zoo exhibit of him.[42]Critiques of Fatalism and Quietism

Critics have accused Slaughterhouse-Five of fostering quietism through its portrayal of Tralfamadorian fatalism, where all events are predetermined and unchangeable, encapsulated in the refrain "so it goes" following descriptions of death.[34] This philosophy, as adopted by protagonist Billy Pilgrim, suggests indifference to suffering, potentially discouraging resistance to atrocities like the Dresden bombing, which Vonnegut witnessed on February 13, 1945.[61] Literary scholar Tony Tanner, for instance, interprets the novel's temporal structure as promoting a passive acceptance of chaos, aligning with quietist tendencies that prioritize resignation over agency.[62] Such readings argue that the Tralfamadorian view—perceiving time as a fixed totality, rendering free will illusory—undermines the novel's anti-war stance by implying wars, like the "glacier" of inevitability Vonnegut describes, cannot be halted.[61] Anthony Burgess critiqued this as evasive, suggesting the repeated "so it goes" normalizes horror without moral reckoning, fostering political inaction amid ongoing conflicts.[34] In this view, Billy's detachment exemplifies how fatalism rationalizes trauma but erodes ethical responsibility, as seen in his equating human deaths with trivial losses, such as spilled champagne.[61] Counterarguments maintain that Vonnegut satirizes rather than endorses fatalism, using Billy's adherence as a flawed psychological defense against World War II horrors, not a prescriptive worldview.[34] The absurdity of Tralfamadorian encounters—possibly hallucinations from Billy's post-traumatic stress—highlights the inadequacy of deterministic resignation, as Vonnegut's authorial intrusions convey outrage and a call to remember the dead, countering quietism with insistent humanity.[63] For example, the novel's ironic tone, per Julian Barnes, reveals "cheerfulness beneath which much pain is hidden," rejecting passive acceptance in favor of confronting war's senselessness.[34] This perspective posits that fatalism serves narrative purposes—to depict trauma's disorientation—while ultimately affirming free will's value through moral emphasis on individual suffering.[41]Historical Foundations

Vonnegut's Dresden Experiences

Kurt Vonnegut was captured by German forces on December 19, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge while serving with the 106th Infantry Division.[2] After initial imprisonment at Stalag IV-B near Dresden, he was selected for a 150-man labor detachment and transported to the city around January 10, 1945.[2] In Dresden, Vonnegut and fellow American prisoners of war worked extended shifts in a malt-syrup factory producing nutritional syrup for pregnant women, subsisting on minimal rations.[2] [64] Each night, the POWs were confined to an underground meat-storage facility in Slaughterhouse Number Five (Schlachthof Fünf), a former municipal abattoir converted into makeshift barracks.[2] The Allied firebombing raids on Dresden occurred from February 13 to 15, 1945. Vonnegut survived the destruction by remaining in the insulated meat locker during the attacks, which leveled much of the city and caused extensive firestorms. In a May 1945 letter to his family from Camp Lucky Strike in France, he described the event: “On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. their combined labors killed 250,000 people in 24 hours and destroyed all of Dresden—possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.”[2] Following the bombing, Vonnegut and other POWs were compelled by their captors to excavate and recover charred bodies from the rubble, a task he later recalled as involving stacking remains "like cordwood."[2] German guards evacuated the prisoners westward ahead of advancing Soviet forces in late April 1945; Vonnegut's group was ultimately liberated by the Red Army in early May 1945.[2]

The Dresden Firebombing: Facts and Strategic Rationale