Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

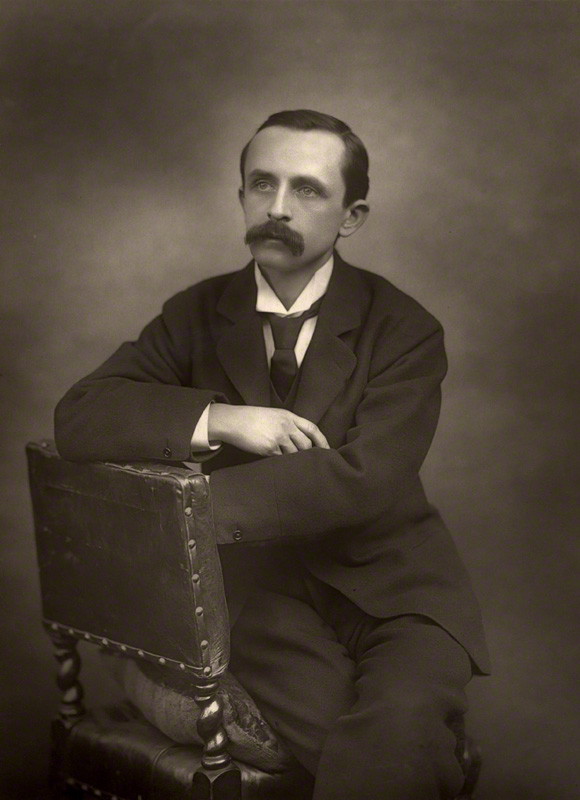

J. M. Barrie

View on Wikipedia

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, OM (/ˈbæri/; 9 May 1860 – 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote several successful novels and plays. There he met the Llewelyn Davies boys, who inspired him to write about a baby boy who has magical adventures in Kensington Gardens (first included in Barrie's 1902 adult novel The Little White Bird), then to write Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up, a 1904 West End "fairy play" about an ageless boy and an ordinary girl named Wendy who have adventures in the fantasy setting of Neverland.

Key Information

Although he continued to write successfully, Peter Pan overshadowed his other work, and is credited with popularising the name Wendy.[1] Barrie unofficially adopted the Davies boys following the deaths of their parents. Barrie was made a baronet by George V on 14 June 1913,[2] and a member of the Order of Merit in the 1922 New Year Honours.[3] Before his death, he gave the rights to the Peter Pan works to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London, which continues to benefit from them.

Childhood and adolescence

[edit]James Matthew Barrie was born in Kirriemuir, Angus, to a conservative Calvinist family. His father, David Barrie, was a modestly successful weaver. His mother, Margaret Ogilvy, assumed her deceased mother's household responsibilities at the age of eight. Barrie was the ninth child of ten (two of whom died before he was born), all of whom were schooled in at least the three Rs in preparation for possible professional careers.[4] He was a small child and drew attention to himself with storytelling.[5] He grew to only 5 ft 31⁄2 in. (161 cm) according to his 1934 passport.[6]

When James Barrie was six years old, his elder brother David (their mother's favourite) died in an ice-skating accident on the day before his 14th birthday.[7] This left his mother devastated, and Barrie tried to fill David's place in his mother's attentions, even wearing David's clothes and whistling in the manner that he did. One time, Barrie entered her room and heard her say, "Is that you?" "I thought it was the dead boy she was speaking to", wrote Barrie in his biographical account of his mother Margaret Ogilvy (1896) "and I said in a little lonely voice, 'No, it's no' him, it's just me.'" Barrie's mother found comfort in the fact that her dead son would remain a boy forever, never to grow up and leave her.[8] Eventually, Barrie and his mother entertained each other with stories of her brief childhood and books such as Robinson Crusoe, works by fellow Scotsman Walter Scott, and The Pilgrim's Progress.[9]

At the age of eight, Barrie was sent to the Glasgow Academy in the care of his eldest siblings, Alexander and Mary Ann, who taught at the school. When he was 10, he returned home and continued his education at the Forfar Academy. At 14, he left home for Dumfries Academy, again under the watch of Alexander and Mary Ann. He became a voracious reader and was fond of penny dreadfuls and the works of Robert Michael Ballantyne and James Fenimore Cooper. At Dumfries, he and his friends spent time in the garden of Moat Brae house, playing pirates "in a sort of Odyssey that was long afterwards to become the play of Peter Pan".[10][11] They formed a drama club, producing his first play Bandelero the Bandit, which provoked a minor controversy following a scathing moral denunciation from a clergyman on the school's governing board.[9]

Literary career

[edit]

Barrie knew that he wished to follow a career as an author; however, his family attempted to persuade him to choose a profession such as the ministry. With advice from Alexander, he was able to work out a compromise of attending a university, but studying literature.[12] Barrie enrolled at the University of Edinburgh where he wrote drama reviews for the Edinburgh Evening Courant. He graduated and obtained an M.A. on 21 April 1882.[12]

Following a job advertisement found by his sister in The Scotsman, he worked for a year and a half as a staff journalist on the Nottingham Journal.[12] Back in Kirriemuir, he submitted a piece to the St. James's Gazette, a London newspaper, using his mother's stories about the town where she grew up (renamed "Thrums"). The editor "liked that Scotch thing" so well that Barrie ended up writing a series of these stories.[9] They served as the basis for his first novels: Auld Licht Idylls (1888), A Window in Thrums (1889),[13] and The Little Minister (1891).

The stories depicted the "Auld Lichts", a strict religious sect to which his grandfather had once belonged.[14] Modern literary criticism of these early works has been unfavourable, tending to disparage them as sentimental and nostalgic depictions of a parochial Scotland, far from the realities of the industrialised 19th century, seen as characteristic of what became known as the Kailyard School.[15] Despite, or perhaps because of, this, they were popular enough at the time to establish Barrie as a successful writer.[14] Following that success, he published Better Dead (1888) privately and at his own expense, but it failed to sell.[16] His two "Tommy" novels, Sentimental Tommy (1896) and Tommy and Grizel (1900), were about a boy and young man who clings to childish fantasy, with an unhappy ending. The English novelist George Gissing read the former in November 1896 and wrote that he "thoroughly dislike[d it]".[17]

Meanwhile, Barrie's attention turned increasingly to works for the theatre, beginning with a biography of Richard Savage, written by Barrie and H. B. Marriott Watson; it was performed only once and critically panned. He immediately followed this with Ibsen's Ghost, or Toole Up-to-Date (1891), a parody of Henrik Ibsen's dramas Hedda Gabler and Ghosts.[14] Ghosts had been unlicensed in the UK until 1914,[18] but had created a sensation at the time from a single "club" performance.

The production of Ibsen's Ghost at Toole's Theatre in London was seen by William Archer, the translator of Ibsen's works into English. Apparently comfortable with the parody, he enjoyed the humour of the play and recommended it to others. Barrie's third play Walker, London (1892) resulted in his being introduced to a young actress named Mary Ansell. He proposed to her and they were married on 9 July 1894. Barrie bought her a Saint Bernard puppy, Porthos, who played a part in the 1902 novel The Little White Bird. He used Ansell's first name for many characters in his novels.[14] Barrie also authored Jane Annie, a comic opera for Richard D'Oyly Carte (1893), which failed; he persuaded Arthur Conan Doyle to revise and finish it for him.

In 1901 and 1902, he had back-to-back successes; Quality Street was about a respectable, responsible old maid who poses as her own flirtatious niece to try to win the attention of a former suitor returned from the war. The Admirable Crichton was a critically acclaimed social commentary with elaborate staging about an aristocratic family and their household servants whose social order is inverted after they are shipwrecked on a desert island. Max Beerbohm thought it "quite the best thing that has happened, in my time, to the British theatre".[19]

Peter Pan

[edit]

The character of "Peter Pan" first appeared in The Little White Bird. The novel was published in the UK by Hodder & Stoughton in 1902 and serialised in the US in the same year in Scribner's Magazine.[20] Barrie's more famous and enduring work Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up had its first stage performance on 27 December 1904 at the West End’s Duke of York's Theatre.[21] The tradition of having a woman play the title role started because at the time children were not allowed to act on stage, and smaller women were considered more believable in the role of a young boy. This play introduced audiences to the name "Wendy"; it was inspired by a young girl named Margaret Henley who called Barrie "Friendy", but could not pronounce her Rs very well.[22] The Bloomsbury scenes show the societal constraints of late Victorian and Edwardian middle class domestic reality, contrasted with Neverland, a world where morality is ambivalent.

George Bernard Shaw described the play as "ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children but really a play for grown-up people", suggesting deeper social metaphors at work in Peter Pan. In 1907, it was parodied by H. G. Pélissier and The Follies at the Apollo Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue in a sketch entitled Baffles or the Peterpan-tomime. This parody was in fact reviewed by Barrie himself in a magazine called Sphere as being "funny in little bits", although he also concluded that The Follies were "one of the funniest things now to be seen in London."[23]

Barrie had a long string of successes on the stage after Peter Pan, many of which discuss social concerns, as Barrie continued to integrate his work and his beliefs. The Twelve Pound Look (1910) concerns a wife leaving her 'typical' husband once she can gain an independent income. Other plays, such as Mary Rose (1920) and Dear Brutus (1917), revisit the idea of the ageless child and parallel worlds. Barrie was involved in the 1909 and 1911 attempts to challenge the censorship of the theatre by the Lord Chamberlain, along with a number of other playwrights.[24]

In 1911, Barrie developed the Peter Pan play into the novel Peter and Wendy. In April 1929, Barrie gave the copyright of the Peter Pan works to Great Ormond Street Hospital, a leading children's hospital in London. The current status of the copyright is somewhat complex. His final play was The Boy David (1936), which dramatised the Biblical story of King Saul and the young David. Like the role of Peter Pan, that of David was played by a woman, Elisabeth Bergner, for whom Barrie wrote the play.[25]

Social connections

[edit]

Barrie moved in literary circles and had many famous friends in addition to his professional collaborators. Novelist George Meredith was an early social patron. He had a long correspondence with fellow Scot Robert Louis Stevenson, who lived in Samoa at the time. Stevenson invited Barrie to visit him, but the two never met.[26][27] He was also friends with fellow Scots writer S. R. Crockett. George Bernard Shaw was his neighbour in London for several years, and once participated in a Western that Barrie scripted and filmed. H. G. Wells was a friend of many years, and tried to intervene when Barrie's marriage fell apart. Barrie met Thomas Hardy through Hugh Clifford while he was staying in London.[27] He was friends with Nobel prize winner John Galsworthy.[28]

Barrie remained tied to his Scottish roots and visited his hometown of Kirriemuir regularly with his wards. When choosing his first personal secretary, Barrie chose E. V. Lucas's wife, Elizabeth Lucas, who had Scottish roots through her American parentage.[29] After Elizabeth Lucas moved to Paris, France, Barrie chose Cynthia Asquith as his personal secretary.

After the First World War, Barrie sometimes stayed at Stanway House near the village of Stanway in Gloucestershire. He paid for the pavilion at Stanway cricket ground.[30] In 1887, he founded an amateur cricket team for friends of similarly limited playing ability, and named it the Allahakbarries under the mistaken belief that "Allah akbar" meant "Heaven help us" in Arabic, rather than "God is great".[31] Some of the best-known British authors from the era played on the team at various times, including H. G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, P. G. Wodehouse, Jerome K. Jerome, G. K. Chesterton, A. A. Milne, E. W. Hornung, A. E. W. Mason, Walter Raleigh, E. V. Lucas, Maurice Hewlett, Owen Seaman (editor of Punch), Bernard Partridge, George Cecil Ives, George Llewelyn Davies (see below) and the son of Alfred Tennyson. In 1891, Barrie joined the newly formed Authors Cricket Club and also played for its cricket team, the Authors XI, alongside Doyle, Wodehouse and Milne. The Allahakbarries and the Authors XI continued to exist side by side until 1912.[9][32]

Barrie befriended Africa explorer Joseph Thomson and Antarctica explorer Robert Falcon Scott.[33] He was godfather to Scott's son Peter,[34] and was one of the seven people to whom Scott wrote letters in the final hours of his life during his expedition to the South Pole, asking Barrie to take care of his wife Kathleen and son Peter. Barrie was so proud of the letter that he carried it around for the rest of his life.[35]

In 1896, his agent Addison Bright persuaded him to meet with Broadway producer Charles Frohman, who became his financial backer and a close friend, as well.[36] Frohman was responsible for producing the debut of Peter Pan in both England and the US, as well as other productions of Barrie's plays. He famously declined a lifeboat seat when the RMS Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat in the North Atlantic. Actress Rita Jolivet stood with Frohman, George Vernon and Captain Alick Scott at the end of Lusitania's sinking, but she survived the sinking and recalled Frohman paraphrasing Peter Pan: 'Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure that life gives us.'[37] Barrie had himself sailed on one of the Lusitania's final Atlantic crossings in September 1914, during which rumours circulated amongst the passengers that the liner was to be transferred to the British Admiralty for troopship duties on arrival in New York.[38]

His secretary from 1917, Cynthia Asquith, was the daughter-in-law of H. H. Asquith, British Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916.[39] In the 1930s, Barrie met and told stories to the young daughters of the Duke of York, the future Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret.[39] After meeting him, the three-year-old Princess Margaret announced, "He is my greatest friend and I am his greatest friend".[27]

Marriage

[edit]Barrie became acquainted with actress Mary Ansell in 1891, when he asked his friend Jerome K. Jerome for a pretty actress to play a role in his play Walker, London. The two became friends, and she helped his family to care for him when he fell very ill in 1893 and 1894.[9] They married in Kirriemuir on 9 July 1894,[40] shortly after Barrie recovered, and Mary retired from the stage. The wedding was a small ceremony in his parents' home, in the Scottish tradition.[41] The relationship was reportedly unconsummated, and the couple had no children.[42]

In 1895, the Barries bought a house on Gloucester Road, in South Kensington.[43] Barrie would take long walks in nearby Kensington Gardens, and in 1900 the couple moved into a house directly overlooking the gardens at 100 Bayswater Road. Mary had a flair for interior design and set about transforming the ground floor, creating two large reception rooms with painted panelling and adding fashionable features, such as a conservatory.[44] In the same year, Mary found Black Lake Cottage at Farnham in Surrey, which became the couple's "bolt hole" where Barrie could entertain his cricketing friends and the Llewelyn Davies family.[45]

Beginning in mid-1908, Mary had an affair with Gilbert Cannan (who was twenty years younger than she[46] and an associate of Barrie in his anti-censorship activities), including a visit together to Black Lake Cottage, known only to the house staff. When Barrie learned of the affair in July 1909, he demanded that she end it, but she refused. To avoid the scandal of divorce, he offered a legal separation if she would agree not to see Cannan any more, but she still refused. Barrie sued for divorce on the grounds of infidelity; the divorce was granted in October 1909.[47][48] Knowing how painful the divorce was for him, some of Barrie's friends wrote to a number of newspaper editors asking them not to publish the story. In the event, only three newspapers did.[49][50] Barrie continued to support Mary financially even after she married Cannan, by giving her an annual allowance, which was handed over at a private dinner held on her and Barrie's wedding anniversary.[46]

Llewelyn Davies family

[edit]

The Llewelyn Davies family played an important part in Barrie's literary and personal life, consisting of Arthur (1863–1907), Sylvia (1866–1910) (daughter of George du Maurier),[51] and their five sons: George (1893–1915), John (Jack) (1894–1959), Peter (1897–1960), Michael (1900–1921) and Nicholas (Nico) (1903–1980).

Barrie became acquainted with the family in 1897, meeting George and Jack (and baby Peter) with their nurse (nanny) Mary Hodgson in London's Kensington Gardens. He lived nearby and often walked his Saint Bernard dog Porthos in the park. He entertained the boys regularly with his ability to wiggle his ears and eyebrows, and with his stories.[52] He did not meet Sylvia until a chance encounter at a dinner party in December. She told Barrie that Peter had been named after the title character in her father's novel, Peter Ibbetson.[53]

Barrie became a regular visitor at the Davies household and a common companion to Sylvia and her boys, despite the fact that both he and she were married to other people.[6] In 1901, he invited the Davies family to Black Lake Cottage, where he produced an album of captioned photographs of the boys acting out a pirate adventure, entitled The Boy Castaways of Black Lake Island. Barrie had two copies made, one of which he gave to Arthur, who misplaced it on a train.[54] The only surviving copy is held at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.[55]

The character of Peter Pan was invented to entertain George and Jack. Barrie would say, to amuse them, that their little brother Peter could fly. He claimed that babies were birds before they were born; parents put bars on nursery windows to keep the little ones from flying away. This grew into a tale of a baby boy who did fly away.[56]

Arthur Llewelyn Davies died in 1907, and "Uncle Jim" became even more involved with the Davies family, providing financial support to them. (His income from Peter Pan and other works was easily adequate to provide for their living expenses and education.)[57] Following Sylvia's death in 1910, Barrie claimed that they had recently been engaged to be married.[58] Her will indicated nothing to that effect but specified her wish for "J. M. B." to be trustee and guardian to the boys, along with her mother Emma, her brother Guy du Maurier and Arthur's brother Compton. It expressed her confidence in Barrie as the boys' caretaker and her wish for "the boys to treat him (& their uncles) with absolute confidence & straightforwardness & to talk to him about everything."[59] When copying the will informally for Sylvia's family a few months later, Barrie inserted himself elsewhere: Sylvia had written that she would like Mary Hodgson, the boys' nurse, to continue taking care of them, and for "Jenny" (referring to Hodgson's sister) to come and help her; Barrie instead wrote, "Jimmy" (Sylvia's nickname for him).[60] Barrie and Hodgson did not get along well but served together as surrogate parents until the boys were grown.[61]

Barrie also had friendships with other children, both before he met the Davies boys and after they had grown up, and there has since been unsubstantiated speculation that Barrie was a paedophile.[62][63] One source for the speculation is a scene in the novel The Little White Bird, in which the protagonist helps a small boy undress for bed, and at the boy's request they sleep in the same bed.[64] However, there is no evidence that Barrie had sexual contact with children, nor that he was suspected of it at the time. Nico, the youngest of the brothers, denied as an adult that Barrie ever behaved inappropriately. "I don't believe that Uncle Jim ever experienced what one might call 'a stirring in the undergrowth' for anyone—man, woman, or child", he stated.[65] "He was an innocent—which is why he could write Peter Pan."[66] His relationships with the surviving Davies boys continued well beyond their childhood and adolescence.

The Peter Pan statue in Kensington Gardens, erected secretly overnight for May Morning in 1912, was supposed to be modelled upon old photographs of Michael dressed as the character. However, the sculptor, Sir George Frampton, used a different child as a model, leaving Barrie disappointed with the result. "It doesn't show the devil in Peter", he said.[67]

Barrie suffered bereavements with the boys, losing the two to whom he was closest in their early twenties. George was killed in action in 1915, in the First World War.[68] Michael, with whom Barrie corresponded daily while at boarding school and university, drowned in 1921, with his friend, Rupert Buxton,[69] at a known danger spot at Sandford Lock near Oxford, one month short of his 21st birthday.[70] Some years after Barrie's death, Peter compiled his Morgue from family letters and papers, interpolated with his own informed comments on his family and their relationship with Barrie. Peter died in 1960 by throwing himself in front of an Underground train at Sloane Square station.

Death

[edit]

Barrie died of pneumonia at a nursing home in Manchester Street, Marylebone on 19 June 1937.[71] He was buried at Kirriemuir next to his parents and two of his siblings.[72] His birthplace at 9 Brechin Road is maintained as a museum by the National Trust for Scotland.[73]

Barrie left the bulk of his estate to his secretary Lady Cynthia Asquith, but excluding the rights to all Peter Pan works (which included The Little White Bird, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, the play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up and the novel Peter and Wendy), whose copyright he had previously given to Great Ormond Street Hospital in London. The surviving Llewelyn Davies boys received legacies, and he made provisions for his former wife Mary Ansell to receive an annuity during her lifetime.[6]

His will also left £500 to the Bower Free Church in Caithness to mark the memory of Rev James Winter who was to have married Barrie's sister in June 1892 but was killed in a fall from his horse in May 1892. Barrie had several connections to the Free Church of Scotland, including his maternal uncle Rev David Ogilvy (1822–1904), who was minister of Dalziel Church in Motherwell.[74] James and his brother William Winter (also a Free Church minister) were both born in Cortachy the sons of Rev William Winter. Cortachy is just west of Kirriemuir and the Winters seem closely connected to the Ogilvy family.[75]

Biographies

[edit]Books

[edit]- Hammerton, J. A. (1929). Barrie: the Story of a Genius. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company.

- Darlington, W. A. (1938). J. M. Barrie. London and Glasgow: Blackie & Son.

- Chalmers, Patrick (1938). The Barrie Inspiration. Peter Davies. ISBN 978-1-4733-1220-3.

- Mackail, Denis (1941). Barrie: The Story of J. M. B. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Dunbar, Janet (1970). J. M. Barrie: The Man Behind the Image. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211384-8.

- Birkin, Andrew (2003). J. M. Barrie and the Lost Boys: The Real Story Behind Peter Pan (Revised ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09822-8.

- Chaney, Lisa (2006). Hide-and-Seek with Angels: A Life of J. M. Barrie. Arrow. ISBN 978-0-09-945323-9.

- Dudgeon, Piers (2009). Captivated: J. M. Barrie, the du Mauriers & the Dark Side of Neverland. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-09-952045-0.

- Telfer, Kevin (2010). Peter Pan's First XI: The Extraordinary Story of J. M. Barrie's Cricket Team. Sceptre. ISBN 978-0-340-91945-3.

- Ridley, Rosalind (2016). Peter Pan and the Mind of J. M. Barrie: An Exploration of Cognition and Consciousness. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-9107-3.

- Dudgeon, Piers (2016). J. M. Barrie and the Boy Who Inspired Him. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1-250-08779-9.

Journal

[edit]- Stokes, Sewell (November 1941). "James M Barrie". New York Theatre Arts Inc. 25 (11): 845–848.

Film, television and stage

[edit]- The Lost Boys (1978). Ian Holm (as J.M. Barrie), Andrew Birkin (writer). BBC.

- The Man Who Was Peter Pan (1998) is a play by Allan Knee, a semi-biographical version of Barrie's life and relationship with the Llewelyn Davies family.

- Finding Neverland (2004) with Johnny Depp (as J.M. Barrie), Kate Winslet (Sylvia Llewelyn Davies), Marc Forster (director), based on Allan Knee's play.

- The Boy James (2012) by Alexander Wright (of Belt Up Theatre), is a one act play inspired by his life and work.

- Finding Neverland (2012) by Diane Paulus, is a musical about the creation of Peter Pan based on the film and starring Matthew Morrison and Laura Michelle Kelly.

Honours

[edit]Personal

[edit]Barrie was created a baronet by King George V in 1913. He was made a member of the Order of Merit in 1922.

In 1919, he was elected Rector of the University of St Andrews for a three-year term. In 1922, he delivered his celebrated Rectorial Address on Courage at St Andrews, and visited University College Dundee with Earl Haig to open its new playing fields, with Barrie bowling a few balls to Haig.[76] He served as Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh from 1930 to 1937.[77]

Barrie was the only person to receive the Freedom of Kirriemuir in a ceremony on 7 June 1930 in Kirriemuir Town Hall where he was presented with a silver casket containing the freedom scroll. The casket was made by silversmiths Brook & Son in Edinburgh in 1929 and is decorated with images of sites in Kirriemuir which held significant memories for Barrie: Kirriemuir Townhouse, Strathview, Window in Thrums, the statue of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and the Barrie Cricket Pavilion. The casket is on display in the Kirrimuir Gateway to the Glens Museum in the Kirriemuir Town House.[78]

|

|

Legacy

[edit]- The Sir James Barrie Primary School in Wandsworth, South West London is named after him.

- The Barrie School in Silver Spring, Maryland, is also named in his honour.[80]

Bibliography

[edit]Peter Pan

[edit]- The Little White Bird, or Adventures in Kensington Gardens (1902)

- Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up (staged 1904, published 1928)

- Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906)

- When Wendy Grew Up: An Afterthought (written – 1908, published 1957)

- Peter and Wendy (novel) (1911)

Other works by year

[edit]- Better Dead (1887)

- Auld Licht Idylls (1888)

- When a Man's Single (1888)

- A Window in Thrums (1889)

- My Lady Nicotine (1890), republished in 1926 with the subtitle A Study in Smoke

- The Little Minister (1891)

- Richard Savage (1891)

- Ibsen's Ghost (Toole Up-to-Date) (1891)

- Walker, London (1892)

- Jane Annie (opera), music by Ernest Ford, libretto by Barrie and Arthur Conan Doyle (1893)

- A Powerful Drug and Other Stories (1893)

- A Tillyloss Scandal (1893)

- Two of Them (1893)

- A Lady's Shoe[81] (1893) (two short stories: A Lady's Shoe, The Inconsiderate Waiter)

- Life in a Country Manse (1894)

- Scotland's Lament: A Poem on the Death of Robert Louis Stevenson (1895)

- Sentimental Tommy, The Story of His Boyhood (1896)

- Margaret Ogilvy (1896)

- Jess[82] (1898)

- Tommy and Grizel (1900)

- The Wedding Guest (1900)

- The Boy Castaways of Black Lake Island (1901)

- Quality Street (play) (1901)

- The Admirable Crichton (play) (1902)

- Little Mary (play) (1903)

- Alice Sit-by-the-Fire (play) (1905)

- Pantaloon (1905)

- What Every Woman Knows (play) (1908)

- Half an Hour[83] (play) (1913)

- Half Hours[84] (1914) includes:

- Pantaloon

- The Twelve-Pound Look (1911)[85]

- Rosalind

- The Will

- The Legend of Leonora (1914)

- Der Tag[86] (The Tragic Man) (Short play) (1914)

- The New Word[87] (play) (1915)

- Charles Frohman: A Tribute (1915)

- Rosy Rapture[88] (play) (1915)

- A Kiss for Cinderella (play) (1916)

- Real Thing at Last[89] (play) (1916)

- Shakespeare's Legacy[90] (play) (1916)

- A Strange Play[91] (play) (1917)

- Charwomen and the War or The Old Lady Shows her Medals[92] (play) (1917)

- Dear Brutus[93] (1917) (play)

- La Politesse[94] (play) (1918)

- Echoes of the War (1918) Four plays, includes:

- The New Word

- The Old Lady Shows Her Medals (basis for the movie Seven Days Leave (1930), starring Gary Cooper)

- A Well-Remembered Voice[95]

- Barbara's Wedding

- Mary Rose (1920)

- Courage, the Rectorial Address delivered at St. Andrews University (1922)

- The Author (1925)

- Biographical Introduction to Scott's Last Expedition (preface) (orig. pub. 1913, introduction included in 1925 edition only)

- Cricket (1926)

- Shall We Join the Ladies?[96] (1928) includes:

- Shall We Join the Ladies?

- Half an Hour

- Seven Women

- Old Friends

- The Greenwood Hat (1930)

- Farewell Miss Julie Logan (1932)

- The Boy David (1936)

- M'Connachie and J. M. B. (1938)

- story treatment for film As You Like It (1936)

- The Reconstruction of the Crime (play), co-written with E.V. Lucas (undated, first published 2017)

- Stories by English Authors: London (selected by Scribners, as contributor)

- Stories by English Authors: Scotland (selected by Scribners, as contributor)

- preface to The Young Visiters or, Mr. Salteena's Plan by Daisy Ashford

- The Earliest Plays of J. M. Barrie: Bandelero the Bandit, Bohemia and Caught Napping, edited by R.D.S. Jack (2014)

References

[edit]- ^ "History of the name Wendy". Wendy.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "No. 28733". The London Gazette. 1 July 1913. p. 4638.

- ^ "No. 32563". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1921. p. 10713.

- ^ Adams, James Eli (2012). A History of Victorian Literature. John Wiley & Sons. p. 359.

- ^ Moffat, Alistair (2012). "Chapter 9". Britain's Last Frontier: A Journey Along the Highland Line. Birlinn. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Birkin, Andrew: J. M. Barrie & the Lost Boys, Constable, 1979; revised edition, Yale University Press, 2003

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 3.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e Chaney, Lisa. Hide-and-Seek with Angels – A Life of J. M. Barrie, London: Arrow Books, 2005

- ^ McConnachie and J. M. B.: Speeches of J. M. Barrie, Peter Davies, 1938

- ^ "Peter Pan project off the ground". BBC News Scotland. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ a b c White (1994), p. 26.

- ^ J. M. Barrie. "A Window in Thrums". Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c d White (1994), p. 27.

- ^ "Kailyard School". www.litencyc.com.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 16.

- ^ Coustillas, Pierre ed. London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: the Diary of George Gissing, Novelist. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1978, p.427.

- ^ Dominic Shellard, et al. The Lord Chamberlain Regrets, 2004, British Library, pp. 77–79.

- ^ "Tales from the cabbage patch". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Cox, Michael (2005). The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 428. ISBN 978-0198610540.

- ^ "Mr Barrie's New Play. A Christmas Fairy Tale". The Glasgow Herald. 28 December 1904. p. 7. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ Winn, Christopher (2005). I Never Knew That About England. Ebury Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780091902070.

- ^ Binns, Anthony; Pélissier, Jaudy (2022). The funniest man in London: the life and times of H.G. Pélissier (1874-1913): forgotten satirist and composer, founder of "The follies". Pett, East Sussex: Edgerton Publishing Services. ISBN 978-0-9933203-8-5.

- ^ Postlewait, Thomas (2004). "The London Stage, 1895–1918". The Cambridge History of British Theatre. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0521651325.

- ^ Law, Jonathan, ed. (2013). The Methuen Drama Dictionary of the Theatre. A & C Black. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1408131480.

- ^ Shaw, Michael (ed.) (2020), A Friendship in Letters: Robert Louis Stevenson & J.M. Barrie, Sandstone Press, Inverness ISBN 978-1-913207-02-1

- ^ a b c Miller, Laura (14 December 2003). "THE LAST WORD; The Lost Boy". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Barker, Dudley (1963). A Man of Principle. London: House and Maxwell. p. 179.

- ^ Sass, Sara (2021). There Are Some Secrets. Atmosphere Press. ISBN 9781639880102.

- ^ Page, William (1965). The Victoria History of the County of Gloucester, Volume 6. A. Constable, limited. p. 226.

- ^ Tim Masters (7 May 2010). "How Peter Pan's author invented celebrity cricket". BBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Parkinson, Justin (26 July 2014). "Authors and actors revive cricket rivalry". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Mark (2 September 2010). "Two friends who took the world by storm". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 209.

- ^ White (1994), p. 36.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 38.

- ^ Ellis, Frederick D., The Tragedy of the Lusitania (National Publishing Company, 1915), pp. 38–39; Preston, Diana, Lusitania, An Epic Tragedy (Walker & Company, 2002), p. 204; New York Tribune, "Frohman Calm; Not Concerned About Death, Welcomed It as Beautiful Adventure, He Told Friends at End", 11 May 1915, p. 3; Marcosson, Isaac Frederick, & Daniel Frohman, Charles Frohman: Manager and Man (John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1916), p. 387; Frohman, Charles, The Lusitania Resource

- ^ Earlier Voyages, Gare Maritime

- ^ a b "Captain Scott and J M Barrie: an unlikely friendship". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "Hall of Fame A–Z: J M Barrie (1860–1937)". National Records of Scotland. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 179–180.

- ^ Stogdon, Catalina (17 May 2006). "Round the houses: Peter Pan". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Law, Cally (10 May 2015). "Return to Neverland". The Sunday Times. Times Newspapers Limited. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "JM Barrie". Surrey Monocle. 10 January 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009. Retrieved from Internet Archive 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey, p. 287

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 175–176, 181.

- ^ "J.M. Barrie Seeks Divorce from Wife". New York Times. 7 October 1909. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

The name of James M. Barrie, the playwright, figures as a petitioner in the list of divorce cases set down for trial at the next session of the law courts here.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 181.

- ^ White (1994), p. 34.

- ^ married the 3Q of 1892 in Hampstead, London: GROMI: vol. 1a, p. 1331

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 41.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 44–45.

- ^ "Andrew Birkin on J. M. Barrie". Jmbarrie.co.uk. 5 April 1960. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2010. Retrieved from Internet Archive 27 December 2013.

- ^ J. M. Barrie's Boy Castaways Archived 15 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- ^ White (1994), p. 29.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 154.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 91–92.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 188–189.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 194.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 196, 271.

- ^ Picardie, Justine (13 July 2008). "How bad was J. M. Barrie?". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Parker, James (22 February 2004). "The real Peter Pan – The Boston Globe". Boston.com. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ White, Donna R. (1994). Zaidman, Laura M. (ed.). British Children's Writers, 1880–1914. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research. ISBN 978-0810355552.

- ^ Birkin (2003), Introduction to the Yale Edition.

- ^ Birkin (2003), p. 130.

- ^ Birkin (2003), pp. 142, 202.

- ^ "Casualty Details: Davies, George Llewelyn". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "Audio". Jmbarrie.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Birkin (2003), Introduction to the Yale Edition, pp. 291–293.

- ^ "Death of Sir J. M. Barrie. King Grieved at Loss of an Old Friend. Funeral on Thursday at Kirriemuil. "The End Was Peaceful"". The Glasgow Herald. 21 June 1937. p. 13. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Funeral of Sir J. M. Barrie. Thousands Assemble at Graveside "Thrums" pays its Last Respects. Distinguished Mourners and Many Tributes". The Glasgow Herald. 25 June 1937. p. 14. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "National Trust for Scotland". National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Ewing, William Annals of the Free Church; James Winter

- ^ Ewing, William Annals of the Free Church; William Winter

- ^ Baxter, Kenneth (29 March 2011). "J M Barrie and Rudyard Kipling". Archives Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "New Chancellor. Installation of James Barrie". The Glasgow Herald. 24 October 1930. p. 13. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "JM Barrie silver casket on show in Kirriemuir". The Scotsman. 12 September 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019.

- ^ Burke's Peerage. 1915. p. 193.

- ^ Carnival PR and Design. "The Barrie School". Barrie.org. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "A Lady's Shoe". www.fadedpage.com.

- ^ "Jess". www.fadedpage.com.

- ^ "Half an Hour". www.fadedpage.com.

- ^ "Half Hours". www.fadedpage.com.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (30 January 2022). "Forgotten Australian Television Plays: The Twelve Pound Look". Filmink. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Der Tag". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "The New Word". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Rosy Rapture". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Real Thing at Last". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Shakespeare's Legacy". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "A Strange play". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Charwomen and the War or The Old Lady Shows Her Medals". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Dear Brutus". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "La Politesse". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "A Well-Remembered Voice". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Shall We Join the Ladies?". www.fadedpage.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Craig, Cairns (1980), Fearful Selves: Character, Community and the Scottish Imagination, in Cencrastus No. 4, Winter 1980-81, pp. 29 – 32, ISSN 0264-0856

- Pick, J.B. (1993), "Fear of the Dark: J.M. Barrie (1860-1937)", in The Great Shadow House: Essays on the Metaphysical Tradition in Scottish Fiction, Polygon, Edinburgh, pp. 53 – 58, ISBN 9780748661169

- Shaw, Michael (ed.) (2020), A Friendship in Letters: Robert Louis Stevenson & J.M. Barrie, Sandstone Press, Inverness ISBN 978-1-913207-02-1

Archival collections

[edit]External links

[edit]- Works by James Matthew Barrie at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about J. M. Barrie at the Internet Archive

- Works by J. M. Barrie at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by J. M. Barrie at Project Gutenberg

- Works by J. M. Barrie in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Peter Pan & Wendy Darling. 11 October 1911. (Peter Pan complete)

- J.M Barrie & 1909 Theatre Censorship Committee – UK Parliament Living Heritage

- JMbarrie.co.uk site authorised by Great Ormond Street Hospital, edited by Andrew Birkin, includes database of original photographs, letters, documents and audio interviews conducted by Birkin in 1975–76

- Great Ormond Street Hospital's copyright claim Archived 11 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Why J. M. Barrie Created Peter Pan", Anthony Lane, The New Yorker, 22 November 2004

- "J. M. Barrie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle" Archived 2 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine at The Chronicles of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (siracd.com)

- Audio recording of Barrie's short play The Will—Recording by professional actors at LostPlays.com

- Film of Barrie from 1922 as Rector of St Andrews with Ellen Terry

- J. M. Barrie at IMDb

- J. M. Barrie at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Plays by J. M. Barrie at the Great War Theatre website

J. M. Barrie

View on GrokipediaSir James Matthew Barrie (9 May 1860 – 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and dramatist renowned for creating Peter Pan, the archetypal boy who refuses to grow up, first introduced in his 1902 novel The Little White Bird and dramatized in the 1904 play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up.[1][2]

Born in Kirriemuir to a modest weaver's family as the ninth of ten children, Barrie drew on personal experiences of loss—including his brother's early death—to infuse his works with themes of perpetual childhood and mortality, achieving early success with novels like Auld Licht Idylls (1888) and the play The Little Minister (1891).[1][3]

His encounters with the Llewelyn Davies boys in Kensington Gardens inspired key elements of Peter Pan, leading to a deep familial bond; after their parents' deaths, Barrie assumed guardianship of the five orphans, bequeathing the play's royalties to Great Ormond Street Hospital in 1929 to support pediatric care.[1][4]

Knighted in 1913 and later honored with the Order of Merit, Barrie's legacy endures through Peter Pan's cultural permeation, though posthumous biographies have debated the platonic nature of his boyhood friendships, with family testimonies affirming no sexual impropriety amid speculative interpretations lacking corroborative evidence.[5][6]

Early Life

Childhood in Kirriemuir

James Matthew Barrie was born on 9 May 1860 at 9 Brechin Road in Kirriemuir, Angus, Scotland, into a conservative Calvinist family of modest means.[1] He was the ninth of ten surviving children born to David Barrie, a handloom weaver whose trade supported the household through linen production in the local industry, and Margaret Ogilvy, who worked as a seamstress and supplemented income by mending clothes.[1][4] The family occupied a small, two-story weaver's cottage, with David's loom positioned on the ground floor amid the sounds of shuttles and threads, while the upper kitchen served as a gathering space warmed by a hearth where Margaret shared oral stories of local folklore and family lore.[4] Daily life in the Barrie home revolved around the rhythms of weaving shifts, Sabbath observance, and frugal domestic routines shaped by Calvinist principles of diligence, thrift, and moral discipline. The household emphasized familial duty and self-reliance, with children contributing to chores such as fetching water from communal pumps or assisting in mending tasks, fostering an environment where imagination served as an escape from material constraints.[1] Kirriemuir's tight-knit community of jute and linen workers, centered around red sandstone tenements and market days, provided a backdrop of communal interdependence amid Scotland's industrial transition from handlooms to mechanized mills.[4] From an early age, Barrie displayed introverted tendencies and a slight build, preferring solitary pursuits over group activities with peers.[1] He often retreated to the wash-house opposite the family home—a disused outbuilding—to invent games and stage impromptu plays using household props, activities that highlighted his propensity for creative solitude and narrative invention amid the town's cobbled lanes and surrounding fields.[1][4] These habits reflected the introspective worldview nurtured by the Calvinist emphasis on inner reflection and the practical limits of a working-class upbringing in rural Angus.Family Dynamics and Brother's Death

David Ogilvy Barrie, the older brother of J.M. Barrie and the favorite of their mother Margaret, died on January 29, 1867, at age 13 from injuries sustained in an ice-skating accident the day before his 14th birthday; he was struck by another skater, fracturing his skull.[7][8] At the time, J.M. Barrie was six years old, and the event plunged the family into mourning, with Margaret displaying an "awful" calmness upon learning of the death before attempting to reach her son, only to find him already deceased.[9] Margaret Ogilvy endured prolonged grief, falling ill for months and expressing sorrow by requesting to see David's christening robe before turning her face to the wall in despair; she lived 29 more years but frequently awoke from sleep bewildered, exclaiming, "My David’s dead!" while having spoken to him in her dreams.[9] To console her, young Barrie sat by her bedside, amusing her with antics such as standing on his head and inquiring, "Are you laughing, mother?"—even tallying her laughs to demonstrate her recovery to a doctor, which elicited further smiles.[9] He also emulated David by donning his clothes, whistling cheerfully, and adopting his posture with legs apart and hands in pockets, triumphantly urging, "Listen!" though these efforts initially pained her, prompting tears before she extended her arms upon his admission, "It’s just me."[9] This dynamic perpetuated David's presence as an unchanging boy in Margaret's mind, providing her solace in the notion that he would "remain a boy forever, never to grow up," a theme Barrie later explored in his writings as rooted in this loss.[10] In Margaret Ogilvy (1896), Barrie recounts how her grief shaped their bond, with his consolations gradually restoring her laughter while David lingered as an eternal figure, influencing Barrie's fixation on arrested development and eternal youth without fully displacing the original sorrow.[9]Initial Education and Formative Influences

James Matthew Barrie began his formal education in Kirriemuir, attending a local private school run by the Misses Adam from around age six, where basic literacy and rudimentary lessons laid the groundwork for his imaginative pursuits amid a resource-scarce environment typical of mid-19th-century Scottish weaving towns.[11] By age eight in 1868, he was sent to the Glasgow Academy, boarding under the supervision of his elder siblings Alexander, a classics master there, and Mary Ann, exposing him to urban scholastic rigor that contrasted sharply with Kirriemuir's rural insularity and fostering early habits of observation and narrative invention through structured classical studies.[1] This period, lasting three years until about 1871, emphasized discipline over creativity, yet Barrie's innate storytelling affinity—honed through family oral traditions—persisted, as evidenced by his later reflections on self-directed reading in Scottish tales during sparse free time.[12] Returning briefly to Forfar Academy around age ten, Barrie continued secondary studies in a regional setting that reinforced Angus dialect patterns, which would causally imprint his early prose with phonetic Scots elements drawn from local speech rather than literary artifice.[13] In 1873, at age thirteen, he transferred to Dumfries Academy, remaining until 1878 under Alexander's oversight as a school inspector, where urban Dumfries' broader intellectual milieu—contrasting Kirriemuir's parochialism—spurred his initial forays into writing, including dialect-infused pieces like "Rekolleckshuns of a Skoolmaster" for the school magazine The Clown in 1875.[14][15] These efforts, amid limited formal creative outlets, empirically trace to self-taught emulation of Scottish vernacular storytellers, with Bible readings from his Calvinist upbringing providing rhythmic prose models that echoed in his whimsical, pathos-laden style.[12] Key formative influences included regional Scottish folklore, absorbed via Kirriemuir's communal yarns and Forfar's oral heritage, which supplied mythic archetypes for Barrie's narrative escapism, distinct from academy curricula focused on classics and arithmetic.[13] Admiration for Robert Louis Stevenson's adventure tales, encountered through personal reading during school sojourns, further shaped his dialect-heavy early output, as Stevenson's vivid Scots-inflected realism demonstrated causal efficacy in blending folklore with psychological depth—evident in Barrie's magazine sketches prioritizing imaginative liberty over academic conformity.[16] This synthesis of sparse formal training and autodidactic immersion in cultural lore cultivated a style rooted in empirical childhood realism, unadorned by elite literary pretensions.[1]Professional Beginnings

Journalism Career

Following his graduation with an M.A. from the University of Edinburgh in 1882, Barrie obtained a position as a leader writer for the Nottingham Journal in early 1883, responding to a job advertisement via mail.[3] [17] In this role, he drafted editorials on current affairs and contributed miscellaneous articles, including pieces under pseudonyms such as "Hippomenes," as in his January 28, 1884, article "Pretty Boys."[18] His tenure lasted approximately one and a half years, during which he developed skills in concise, persuasive prose and local reporting, though much of the work involved routine tasks amid the paper's declining fortunes.[19] [20] After departing Nottingham in mid-1884 and briefly returning to Kirriemuir, Barrie submitted sketches to London periodicals, with the St. James's Gazette accepting his first "Auld Licht" piece, "An Auld Licht Community," in October 1884.[21] These vignettes, drawing on his mother's anecdotes of Scottish rural customs, marked his shift toward satirical, character-driven journalism. Relocating to London on March 28, 1885, he freelanced for the Gazette under editor Frederick Greenwood, producing further installments that explored "Auld Licht" (Old Light) Presbyterian life with wry observation, such as "An Auld Licht Scandal" and "An Auld Licht Funeral" in 1885.[22] [23] This period refined his humorous style, emphasizing everyday absurdities over grand narrative, though syndication remained limited and earnings modest as he supplemented income across outlets like the British Weekly.[24] Barrie's journalistic output, including pseudonymous contributions on topics like youth and local customs, fostered audience familiarity without instant fame, providing empirical training in audience engagement and deadline precision that causally underpinned his transition to fiction.[18] By 1887, the collected "Auld Licht" essays formed the basis of his debut book, demonstrating how sustained newspaper work built a foundation for literary pursuits amid initial professional setbacks, such as unremarked submissions.[21]Early Literary Output

Barrie's debut novel, Better Dead, published on 19 November 1887 by Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co., comprised a satirical shilling shocker centered on the Society for the Prevention of the Extinction of Useless Creatures, which targeted politicians, suffragettes, and literary figures for elimination as "better dead."[25] Contemporary reviews lauded its clever topical allusions, with The Academy on 7 January 1888 calling it the "best skit...for a long time," though others faulted its superficiality and lack of depth.[25] Initial sales proved modest within the competitive shilling fiction market, but reprints extended through 1903, yielding Barrie £68 19s 2d by 1893 after profits from later works.[25] Auld Licht Idylls, a collection of sketches issued in April 1888, drew directly from Kirriemuir life, fictionalized as Thrums, to depict the austere piety of the "Auld Licht" Presbyterians—a strict secessionist sect—with whimsical portrayals of rural Scottish customs and dialect.[25] The volume garnered immediate critical enthusiasm for its authentic evocation of provincial existence, achieving modest commercial viability that retroactively boosted Better Dead's earnings.[25] The Little Minister, Barrie's semi-autobiographical 1891 novel set amid Thrums's weaving community and rigid religious observances, was first serialized in Good Words magazine from January to December.[26] Published in book form by Cassell & Co., it sold 24,000 copies in its first fourteen months, including 7,000 exported to colonies, providing Barrie his initial substantial financial stability through royalties.[27] These early Thrums works blended themes of Scottish Calvinist piety—evident in portrayals of doctrinal fervor and moral austerity—with light whimsy, though their nostalgic rural focus later invited criticism for undue sentimentality in evoking parochial life.[28]Literary Achievements

Novels and Short Stories

Barrie's novels and short stories transitioned from depictions of Scottish provincial life to introspective examinations of boyhood fantasy and arrested development, reflecting personal influences such as his mother's idealized memory of his deceased brother David. His initial short story collections, including Auld Licht Idylls (1888), comprised semi-autobiographical sketches of Thrums—a fictionalized Kirriemuir—focusing on rigid Presbyterian customs, familial duties, and the quiet dramas of working-class existence.[29] These pieces emphasized realism tempered by sentiment, portraying characters bound by tradition and stoic endurance amid economic hardship.[30] Sentimental Tommy: The Story of His Boyhood (1896) marked a pivot toward child-centric narratives, chronicling the orphaned Tommy Sandys, a precocious London slum-dweller whose inventive lies and romantic escapism propel him to rural Scotland, where he grapples with maturation.[31] The novel draws autobiographical parallels to Barrie's youth, including themes of maternal devotion and fabricated personas to sustain innocence, though contemporary assessments highlighted its sentimental excess and melodramatic plotting as detracting from psychological nuance.[26] The sequel, Tommy and Grizel (1900), traces Tommy's adulthood as a writer, where his refusal to relinquish boyish illusions undermines romantic fulfillment with Grizel, culminating in estrangement and regret.[32] This extension underscores causal tensions between fantasy-clinging and relational viability, with Tommy's emotional stunting mirroring Barrie's self-perceived maturational deficits, informed by his marital strains.[33] The Little White Bird (1902) further blended prosaic adult narration with fantastical interludes, centering an unnamed bachelor's bond with young David and introducing Peter Pan as a Kensington Gardens sprite who rejects growth to retain avian freedom.[34] Serialized portions evolved into expanded fantasy segments, evidencing Barrie's stylistic fusion of Kensington social observation and ethereal escapism, which garnered modest acclaim for innovation prior to his dramatic renown.[35] These works collectively trace a thematic arc from communal realism to individualized puer aeternus motifs, achieving niche readerships through Hodder & Stoughton and Scribner's editions before broader theatrical fame.Breakthrough in Theatre

Barrie's transition to playwriting in the early 1890s reflected a preference for the theatre's direct audience engagement, which offered rapid validation and revision opportunities absent in the slower reception of novels, whose sales had been modest despite critical notice.[36] This pivot aligned with a broader demand for light comedies amid fatigue with realist dramas like those of Ibsen.[37] Walker, London (1892), a comedic sketch of urban provincialism, premiered successfully in London, securing Barrie's initial West End foothold and introducing him to actress Mary Ansell during production.[38] The Professor's Love Story (1894), a whimsical romance centered on an absent-minded academic's courtship, achieved commercial viability with sustained stagings through 1916, underscoring its appeal in blending sentiment and humor.[39] These efforts culminated in more ambitious satires: Quality Street (1901), which lampooned Regency-era gender expectations through a spinster's masquerade as a youthful ingénue, opened in New York with Maude Adams before a London run of 459 performances in 1902, cementing Barrie's rapport with leading actors.[40] The Admirable Crichton (1902), depicting a butler's natural leadership inverting class structures after a marooning, critiqued aristocratic inertia via farce, drawing packed houses and critical praise for its inversion of social Darwinism.[41] Such longevity—exemplified by runs exceeding typical fare—elevated Barrie from journalistic roots to a dominant theatrical voice, fostering collaborations that amplified his whimsical yet probing style.[39]Peter Pan: Origins and Premieres

The character of Peter Pan originated in J. M. Barrie's 1902 novel The Little White Bird, where chapters 13 through 18 depict a fantastical infant who flies away from his London home to Kensington Gardens, introducing elements of eternal youth and detachment from adulthood.[34] These chapters expanded on Barrie's imaginative tales shared during walks in Kensington Gardens with the Llewelyn Davies children, whom he encountered starting in 1897, incorporating playful scenarios that evolved into the play's core motifs of flight, adventure, and resistance to growing up.[42] Barrie conceptualized the full stage adaptation as Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up, drawing from these vignettes to create a narrative bridging nursery life with the mythical island of Neverland, populated by the Lost Boys, the Darling children including Wendy, and antagonists like Captain Hook.[43] The play premiered on December 27, 1904, at the Duke of York's Theatre in London, produced by Charles Frohman with innovative staging including wire harnesses for flying sequences and elaborate scenery depicting the shift from a realistic nursery to Neverland's landscapes.[43] [44] Barrie undertook multiple script revisions prior to and during early performances, refining dialogue and action to heighten dramatic tension—such as amplifying Peter's ambivalence toward maturity—while retaining philosophical undertones on mortality, evidenced by lines where Peter dismisses death as a "great big nothing."[45] The production faced technical challenges, including delayed flights and prop malfunctions on opening night, yet these were overcome to deliver a spectacle blending pantomime traditions with Barrie's whimsy.[46] Initial runs from 1904 to 1905 totaled 145 performances, establishing financial success that yielded Barrie royalties exceeding £1,000 annually by 1905 and securing rights management through Frohman's agency.[47] [48] Contemporary reviews lauded the play's inventive charm and appeal to mixed audiences, with The Times praising its "delightful absurdity," though some critics discerned veiled pessimism beneath the fantasy, noting Peter's eternal boyhood as a poignant evasion of life's inevitable losses rather than pure escapism.[45] The production's extended engagement until 1913 at various London venues cemented its status as a holiday staple, prompting annual revivals that amplified its cultural footprint while Barrie continued tweaking the text for clarity and emotional depth.[49]Subsequent Plays and Productions

Following the success of Peter Pan in 1904, J. M. Barrie continued to produce plays that often revisited themes of fantasy, regret, and the passage of time, though critics noted a shift toward more introspective and repetitive structures compared to his earlier inventive works. What Every Woman Knows, premiered on September 3, 1908, at the Duke of York's Theatre in London, examined marital dynamics through the story of Maggie Wylie, an unassuming Scottish woman whose subtle influence propels her husband's political career, blending social satire with observations on gender roles and ambition.[50] The play achieved commercial success, reflecting Barrie's established formula of witty domestic comedy laced with sentimentality, yet some contemporaries viewed it as less groundbreaking than his prior fantasies, relying on predictable character arcs and resolutions.[51] Barrie's output slowed during World War I, but Dear Brutus opened in late 1917 at Wyndham's Theatre in London, running until August 24, 1918, amid the war's final year, which infused its premise with timely resonance.[52] The fantasy posits a group of dissatisfied guests at a country house who enter a magical wood granting a second chance at youth to revisit past regrets, echoing Peter Pan's refusal of maturity but transposed to adult disillusionment and self-deception. Productions capitalized on its wartime escapism, though the play's structure—alternating realism with supernatural intervention—drew critiques for formulaic repetition of Barrie's motif of alternate realities, prioritizing emotional catharsis over narrative innovation.[53] In the post-war period, Mary Rose debuted on April 22, 1920, at the Haymarket Theatre in London, achieving a respectable run of 433 performances.[54] The supernatural drama centers on a young mother who vanishes on a remote island, reappearing unchanged years later, only to disappear again, exploring eternal youth and maternal loss in a haunting parallel to Barrie's earlier fixation on timeless childhood. While thematically cohesive with his oeuvre, the play's introspective tone and reliance on ghostly revelation marked a departure from vibrant adventure toward melancholic stasis, with shorter relative endurance in revivals signaling audience fatigue with Barrie's recurring motifs of suspended time and unresolved longing.[55] Later works exhibited fewer extended West End runs and a perceptible turn inward, contrasting the sustained vitality of pre-war hits like The Admirable Crichton (1902, over 500 performances), as Barrie grappled with typecasting in whimsical fantasy amid evolving theatrical tastes.[52]Personal Life

Marriage and Domestic Challenges

J. M. Barrie married actress Mary Ansell on July 9, 1894, in a small ceremony at his parents' home in Kirriemuir, Scotland.[56] Ansell had met Barrie while starring in his 1892 play Walker, London, and the union followed Barrie's recovery from illness.[57] The marriage produced no children.[57] Initial reports described the couple as happy, with Ansell retiring from the stage upon marriage.[58] However, strains emerged over time, marked by incompatibility rather than allegations of abuse or mistreatment. In mid-1908, Ansell began an affair with writer Gilbert Cannan, approximately 20 years her junior.[57] Barrie discovered the relationship and demanded its end, but Ansell refused.[57] Barrie filed for divorce on grounds of Ansell's infidelity in 1909, with the decree granted in October of that year.[59] During proceedings, Ansell claimed the marriage had never been consummated, a detail Barrie did not publicly refute.[60] Barrie provided Ansell with a financial settlement following the divorce, allowing her to remarry Cannan in April 1910.[61]Social and Literary Networks

J. M. Barrie participated in elite literary circles through memberships in dining clubs such as the Omar Khayyam Club, founded in 1895 to celebrate the poet and attract prominent writers including Arthur Conan Doyle.[62] [63] In 1902, Barrie confirmed his subscription to the club via correspondence, underscoring his engagement in these convivial gatherings that fostered intellectual exchange among London's literary elite.[64] Barrie shared a longstanding friendship with Arthur Conan Doyle, marked by mutual professional support and recreational activities; the two co-founded a cricket team in 1893 comprising authors and artists, which played matches into the early 1900s and symbolized their collaborative spirit.[65] [66] They occasionally collaborated, as when Barrie sought Doyle's assistance in plotting a story, reflecting a network built on shared creative challenges rather than rivalry.[67] Barrie maintained epistolary ties with Robert Louis Stevenson from 1892 until Stevenson's death in 1894, exchanging letters that revealed deep mutual respect and Barrie's admiration for Stevenson's work, including playful claims of shared Scottish ancestry.[68] [69] These correspondences extended indirectly to Stevenson's circle, preserving literary continuity across distances. Barrie's professional alliance with theatrical producer Charles Frohman, beginning around 1900, facilitated transatlantic premieres of his plays, including Peter Pan in 1904; Frohman's management of over 700 productions bolstered Barrie's visibility.[70] Frohman's death on May 7, 1915, aboard the RMS Lusitania disrupted this partnership, coinciding with a decline in Barrie's theatrical output as he grappled with the loss of a key collaborator. [71] In Edinburgh and London, Barrie served as a benefactor within Scottish literary institutions, such as granting £400 to the Dumfries Burns Club in 1918, which earned him life membership and exemplified his non-exploitative support for cultural preservation and nascent talents amid elite networks.[72]Bond with the Llewelyn Davies Boys

J. M. Barrie first encountered the eldest Llewelyn Davies boy, George, in Kensington Gardens in 1897 while walking his St. Bernard dog, Porthos, leading to acquaintance with the family including Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and their five sons: George (born 1893), John (Jack, 1894), Peter (1897), Michael (1900), and Nicholas (Nico, 1903).[73][5] Over the following years, Barrie regularly engaged with the boys through storytelling and games in the gardens, fostering a close friendship with the parents by 1900.[1] These interactions inspired elements of Peter Pan, with the character Peter named after Peter Llewelyn Davies.[73] Arthur Llewelyn Davies died of bone cancer on April 19, 1907, followed by Sylvia on August 27, 1910, from the same disease; in her will, Sylvia appointed Barrie alongside the boys' uncles as co-guardians.[74][75] Barrie assumed significant responsibilities, providing financial support for their education and upkeep, including funding university fees and arranging shared holidays at his Scottish retreat.[76][39] He incorporated codicils into his own will in 1910 and 1934 to ensure ongoing provisions for the boys.[77] Barrie's correspondence with the boys, such as letters to Michael expressing delight in their updates and playful encouragement, reflected affectionate, imaginative engagement without physical intimacy.[78] No contemporary records indicate complaints from the boys or guardians regarding his involvement. The youngest, Nico Llewelyn Davies, in 1970s interviews including a 1978 BBC discussion, described Barrie as a "perfect uncle" who provided paternal guidance and laughter, affirming the bond's positive nature into adulthood.[79][80] Tragedy marked the family when Michael drowned on May 19, 1921, at age 20, alongside friend Rupert Buxton in the dangerous Sandford Lasher pool near Oxford, shortly before his 21st birthday.[81] Barrie continued supporting the surviving brothers through their careers and personal challenges, maintaining the relationship until his death in 1937.[73]Controversies

Claims of Inappropriate Conduct with Children

Allegations of inappropriate conduct by J. M. Barrie toward children, particularly the Llewelyn Davies boys, have primarily arisen from interpretive analyses in 20th- and 21st-century biographies rather than contemporary accusations or direct testimony from the individuals involved. Piers Dudgeon, in his 2005 biography Hide-and-Seek with Angels: A Life of J. M. Barrie, portrayed Barrie's extensive correspondence with the boys—including letters crafted as bedtime stories sent by post and playful invitations to Kensington Gardens meetings—as suggestive of grooming and emotional manipulation, framing the relationship within a pattern of psychological control over the family.[82] Similar speculations appear in Dudgeon's later works, such as Captivated (2008), which emphasize Barrie's intense focus on the boys following their parents' deaths in 1907 and 1910, interpreting it as exploitative rather than benevolent.[83] These claims are contested by biographers drawing on primary family sources, notably Andrew Birkin's J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys (1979, revised editions), which utilized unpublished letters, diaries, and interviews with the surviving boys and their descendants to argue that no evidence exists of sexual abuse or physical impropriety. Birkin documented Barrie's role as informal guardian and financial benefactor—leaving his substantial estate to the boys in 1937—while highlighting the absence of any contemporaneous complaints; the boys' own accounts reflected mutual affection and playfulness consistent with Edwardian social norms, where adult men engaging in childlike games with orphans was not uncommon.[84] Descendants, including Nico Llewelyn Davies's daughter Laura, have affirmed this view, describing Barrie's affinity for children as paternal and devoid of sexual undertones in a 2003 documentary featurette.[5] Recent reassessments further challenge predatory interpretations, attributing Barrie's child-centric behavior to asexuality and unresolved trauma from his brother David's death in 1867, which stunted his emotional maturation—a condition akin to "Peter Pan Syndrome" rather than pedophilic intent. A 2024 analysis in The Times references a new biography concluding Barrie posed no threat to children, countering decades of speculation by emphasizing platonic bonds over sinister motives.[85] While critics like Dudgeon invoke modern psychological lenses to infer harm from emotional dependency, no verifiable records of misconduct emerge from the boys' lives or Barrie's papers; tragic outcomes for some, such as Michael's 1921 drowning, are linked by family and biographers to World War I traumas rather than abuse.[5] This debate underscores tensions between retrospective moral judgments and historical context, with defenders prioritizing empirical absence of harm against accusers' reliance on circumstantial inference.Debates on Sexuality and Psychological Profile

Barrie, who stood at roughly 4 feet 11 inches tall throughout his adult life, frequently alluded to his own physical and emotional immaturity in personal correspondence during the 1890s, attributing it to an early cessation of growth possibly linked to health issues in youth, which he connected to a broader absence of sexual development.[37] In letters to friends and family, he described himself as lacking typical adult drives, emphasizing a perpetual childlike state that precluded conventional romantic or physical intimacy.[86] His 1894 marriage to actress Mary Ansell ended in divorce in 1909, with court testimony confirming the union was never consummated due to Barrie's impotence, a claim corroborated by Ansell's affidavits and contemporary reports lacking any counter-evidence of physical relations.[58] [86] Medical examinations during this period, including those related to his brief military involvement, noted no overt pathologies beyond his diminutive stature but aligned with self-reported frigidity, suggesting psychogenic rather than organic causes rooted in psychological factors.[37] Biographical debates have centered on whether Barrie's celibacy indicated asexuality, repressed homosexuality, or Victorian-era sexual repression. Proponents of the latter theory cite his documented infatuations with male actors and writers, such as Jerome K. Jerome, interpreting intense homosocial bonds in his works and letters as veiled eroticism; however, these interpretations rely on retrospective psychoanalytic frameworks lacking direct evidence of homosexual acts, with no scandals or accusations emerging despite the era's scrutiny of such behaviors.[87] Biographer Andrew Birkin, drawing on family archives and personal papers, argues for innate asexuality, noting Barrie's consistent disinterest in sex across genders and the absence of any intimate adult relationships post-divorce, a view echoed by Llewelyn Davies family members who described him as devoid of carnal pursuits.[88] [5] Such speculations often project modern categories onto Victorian norms, where celibacy among intellectuals was not uncommon and did not imply pathology; empirical priority favors Barrie's own accounts and proximate testimonies over anachronistic Freudian readings, which risk overpathologizing restraint amid cultural taboos on sexuality.[32] Friends and collaborators, including those privy to his private life, reported no deviations from platonic affections, underscoring a causal link to personal temperament rather than suppressed deviance.[89]Responses from Biographers and Family

Andrew Birkin's 1979 biography J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys, revised and expanded in 2003, drew on extensive archival research including family letters and interviews with Nicholas "Nico" Llewelyn Davies, the youngest of the brothers, who explicitly denied any sexual impropriety by Barrie toward the boys, describing their relationship as affectionate but non-physical.[90] Birkin prioritized primary documents such as correspondence and diaries over speculative interpretations, concluding that claims of pedophilia lacked evidentiary support and stemmed from Barrie's unconventional emotional attachments rather than erotic intent.[89] This approach contrasted with earlier 1930s rumors, amplified post-Barrie's 1909 divorce, which alleged impropriety without contemporaneous complaints from the family or witnesses.[89] Piers Dudgeon's 2009 book Neverland: J.M. Barrie, the Du Mauriers, and the Dark Side of Peter Pan exemplified a more sensational methodology, positing Barrie's influence as a form of hypnotic domination that precipitated family tragedies, including suicides, while sidestepping direct pedophilia accusations in favor of psychological coercion theories derived from circumstantial links to mesmerism trends.[83] Critics noted Dudgeon's reliance on inference over verifiable records, such as ignoring the boys' adult affirmations of platonic bonds and attributing unrelated personal misfortunes—like Michael Llewelyn Davies's 1921 drowning—to Barrie's orbit without causal proof.[91] Family rebuttals underscored empirical denials: Nico Llewelyn Davies, in letters to Birkin during the 1970s, reiterated that Barrie exhibited no predatory behavior, countering posthumous narratives with firsthand recollection of a guardian-like figure amid parental losses.[92] Peter Llewelyn Davies's 1960 suicide, occurring on April 5 in a London railway station, was ruled by inquest as resulting from depression exacerbated by war service and business failures, with no note or evidence implicating Barrie, as Peter's prior writings expressed pity for Barrie's personal unhappiness rather than blame.[93] These primary accounts highlight the primacy of direct testimony over conjectural "Peter Panic"—a term for amplified pedophilia fears in late-20th-century media and scholarship—which often prioritized psychoanalytic conjecture amid cultural anxieties, sometimes reflecting institutional biases toward pathologizing non-conforming male-child bonds without proportional scrutiny of exonerating sources.[5] Recent evaluations, including 2024 reassessments, reinforce this by debunking such claims through re-examination of archives, noting their persistence via selective amplification in outlets favoring unverified sensationalism over family-verified platonic dynamics.[5]Later Years

Philanthropic Efforts

In 1929, J.M. Barrie transferred the copyright of his play Peter Pan—along with rights to its novelizations—to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London, granting the institution perpetual royalties from performances, publications, and adaptations.[77][94] This gift, formally announced at a Guildhall banquet on 8 October 1929, was motivated by Barrie's longstanding advocacy for pediatric care, stemming from his personal visits to the hospital and interactions with its young patients; contemporary estimates projected an annual income of approximately £2,000 for the hospital, though the true figure has since amassed millions in inflation-adjusted terms to fund treatments and expansions.[95][96] Barrie stipulated that royalty amounts remain undisclosed to avoid publicity, a condition the hospital has honored, underscoring his preference for discreet philanthropy over public acclaim.[94] Barrie's charitable activities extended beyond this landmark donation to include anonymous contributions to child welfare initiatives, such as aid for war orphans following the First World War and support for a hospital in France during wartime hardships.[97] These efforts reflected a pattern of private, targeted giving rooted in paternalistic concern for vulnerable children, akin to his financial assistance for the Llewelyn Davies family, prioritizing individual and institutional aid over broader state mechanisms. Biographer Cynthia Asquith, who served as his secretary, documented numerous such gifts, often funneled through trusted intermediaries to maintain anonymity.[39] Upon probate of his estate in 1937, Barrie's will included modest bequests to charities, but these paled against his lifetime disbursements, which had already distributed substantial sums to pediatric and Scottish heritage causes without fanfare.[97] This approach exemplified a commitment to empirical impact—verifiable through hospital records and beneficiary accounts—rather than symbolic gestures, ensuring resources directly alleviated child suffering amid limited public welfare systems of the era.[39]Health Decline and Death

Barrie's health had long been compromised by a frail constitution and respiratory vulnerabilities stemming from childhood illnesses, which limited his stamina in later decades. After World War I, he withdrew from composing new works, instead overseeing revisions to earlier plays and engaging in patronage roles, as his energy waned.[2] In early June 1937, acute illness prompted his admission to a nursing home at 25 Manchester Street in Marylebone, London, on June 11, where broncho-pneumonia set in as the terminal condition.[98] He died there on June 19, 1937, aged 77, with family members including adopted son Peter Llewelyn Davies at his bedside.[99] His remains were cremated at Golders Green Crematorium, with ashes subsequently interred in Kirriemuir Kirkyard beside his parents and siblings.[100] The funeral proceedings reflected his baronet status with dignified private rites, free of any contemporaneous scandals or public disputes over his legacy. Barrie's will directed the perpetual royalties from Peter Pan to Great Ormond Street Hospital for children, securing ongoing support for pediatric care without immediate legal challenges.[2]Legacy

Honours and Recognition