Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Social services

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Social services are a range of public services intended to provide support and assistance towards particular groups, which commonly include the disadvantaged.[1] They may be provided by individuals, private and independent organizations, or administered by a government agency.[1] Social services are connected with the concept of welfare and the welfare state, as countries with large welfare programs often provide a wide range of social services.[2] Social services are employed to address the wide range of needs of a society.[2] Prior to industrialisation, the provision of social services was largely confined to private organisations and charities, with the extent of its coverage also limited.[3] Social services are now generally regarded globally as a 'necessary function' of society and a mechanism through which governments may address societal issues.[4]

The provision of social services by governments is linked to the belief of universal human rights, democratic principles, as well as religious and cultural values.[5] The availability and coverage of social services varies significantly within societies.[6][4] The main groups which social services is catered toward are: families, children, youths, elders, women, the sick, and the disabled.[4] Social services consists of facilities and services such as: public education, welfare, infrastructure, mail, libraries, social work, food banks, universal health care, police, fire services, public transport and public housing.[7][2]

Characteristics

[edit]

The term 'social services' is often substituted with other terms such as social welfare, social protection, social assistance, social care and social work, with many of the terms overlapping in characteristics and features.[1][4] What is considered a 'social service' in a specific country is determined by its history, cultural norms, political system and economic status.[1][4] The most central aspects of social services include education, health services, housing programs, and transport services.[7] Social services can be both communal and individually based.[1] This means that they may be implemented to provide assistance to the community broadly, such as economic support for unemployed citizens, or they may be administered specifically considering the need of an individual – such as foster homes.[1] Social services are provided through a variety of models.[1] Some of these models include:[1]

- The Scandinavian model: based on the principles within 'universalism'. This model provides significant aid to disadvantaged groups such as people with disabilities and is administered through the local government with limited contributions from non-governmental organisations.[1]

- The family care model: employed throughout the Mediterranean, this model relies on the aid of individuals and families which usually work with clergy, as well as that of NGOs such as the Red Cross.[1]

- The means-tested model: employed in the UK and Australia, the government provides support but has stringent regulations and checks which it employs to determine who is entitled to receive social services or assistance.[1]

Recipients

[edit]Social services may be available to the entirety of the population, such as the police and fire services, or they may be available to only specific groups or sections of society.[1] Some examples of social service recipients include elderly people, children and families, people with disabilities, including both physical and mental disabilities.[1] These may extend to drug users, young offenders and refugees and asylum seekers depending on the country and its social service programs, as well as the presence of non-governmental organisations.[1]

History

[edit]Early developments

[edit]The development of social services increased significantly in the last two decades of the nineteenth century in Europe.[8] There are a number of factors that contributed to the development of social services in this period. These include: the impacts of industrialisation and urbanisation, the influence of Protestant thought regarding state responsibility for welfare, and the growing influence of trade unions and the labour movement.[8][3]

Europe (1833–1914)

[edit]

In the nineteenth century, as countries industrialised further, the extent of social services in the form of labour schemes and compensation expanded. The expansion of social services began following Britain's legislation of the 1833 Factory Act.[9] The legislation set limits on the minimum age of children working, preventing children younger than nine years of age from working.[9] Additionally, the Act set a limit of 48 working hours per week for children aged 9 to 13, and for children aged 13 to 18 it was set at 12 hours per day.[9] The Act also was the first legislation requiring compulsory schooling within Britain.[9] Another central development for the existence of social services was Switzerland's legislation of the Factory Act in 1877.[10] The Factory Act introduced limitations on working hours, provided maternity benefits and provided workplace protections for children and young adults.[10] In Germany, Otto von Bismarck also introduced a large amount of social welfare legislation in this period.[10] Mandatory sickness insurance was introduced in 1883, with workplace accident insurance enacted in 1884 alongside old age and invalidity schemes in 1889.[10] Insurance laws of this kind were emulated in other European countries afterwards, with Sweden enacting voluntary sickness insurance in 1892, Denmark in 1892, Belgium in 1894, Switzerland in 1911, and Italy in 1886.[8] Additionally, Belgium, France and Italy enacted legislation subsidising voluntary old-age insurance in this period.[8] By the time the Netherlands introduced compulsory sickness insurance in 1913, all major European countries had introduced some form of insurance scheme.[8]

South America (1910–1960)

[edit]According to Carmelo Meso-Lago, social services and welfare systems within South America developed in three separate stages, with three groups of countries developing at different rates.[3] The first group, consisting of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay, developed social insurance schemes in the late 1910s and the 1920s.[3] The notable schemes, which had been implemented by 1950, consisted of work injury insurance, pensions, and sickness and maternity insurance.[3] The second group, consisting of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela, implemented these social services in the 1940s.[3] The extent to which these programs and laws were implemented were less extensive than the first group.[3] In the final group, consisting of the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras and Nicaragua, social services programmes were implemented in the 1950s and 1960s, with the least coverage out of each group.[3] With the exception of Nicaragua, social service programs are not available for unemployment insurance or family allowances.[3] Average expenditure on social services programs in as a percentage of GDP in these states is 5.3%, which is significantly lower than that of Europe and North America.[3]

Asia (1950–2000)

[edit]

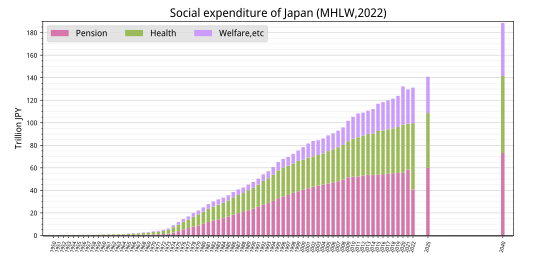

Within Asia, the significant development of social services first began in Japan after the conclusion of World War II.[5] Due to rising levels of social inequality in the 1950s following the reformation of the Japanese economy, the incumbent Liberal Democratic Party legislated extensive health insurance laws in 1958 and pensions in 1959 to address societal upheaval.[5] In Singapore, a compulsory superannuation scheme was introduced in 1955.[5] Within Korea, voluntary health insurance was made available in 1963 and mandated in 1976.[5] Private insurance was only available to citizens employed by large corporate firms, while a separate insurance plans were provided to Civil Servants and military personnel.[5] In Taiwan, the Kuomintang government in 1953 propagated a healthcare inclusive workers insurance programme.[5] A separate insurance scheme for bureaucrats and the military was also provided in Korea in this time.[5] In 1968, Singapore increased its social services program to include public housing, and expanding this further in 1984 to include medical care.[5] Within both Korea and Taiwan, by the 1980s the number of workers that were covered by labour insurance had not increased above 20%.[5]

Following domestic political upheaval within Asian countries in the 1980s, the availability social services considerably increased in the region.[5] In 1988 in Korea, health insurance was granted to self-employed rural workers, with coverage extended to urban-based self-employed workers in 1989. Additionally, a national pension program was initiated.[5] Within Taiwan, an extensive national health insurance system was enacted in 1994 and implemented in 1995.[5] During this period the Japanese government also expanded social services for children and the elderly, providing increased support services, increasing funding to care facilities and organisations, and legislating new insurance programs.[5] In the 1990s, Shanghai introduced a housing affordability program which was then later expanded to include all of China.[5] In 2000, Hong Kong introduced a superannuation scheme policy, with China implementing a similar policy soon after.[5]

Types

[edit]- Healthcare

- Education

- Police

- Labour Laws

- Fire Services

- Insurance laws

- Food banks

- Charitable Organisations

- Public housing

- Aged Care

- Disability Services

- Legal aid

- Youth Services

- Crisis Support Services

- Emergency Relief

- Public transportation

Impacts

[edit]Quality of life

[edit]There have been several findings which indicate that social services have a positive impact upon the quality of life of individuals. An OECD study in 2011 found that the countries with the highest ratings were Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland, while the lowest ratings were given by people from Estonia, Portugal and Hungary.[12] Another study recorded by the Global Barometer of Happiness in 2011 found similar results.[12] Both of these studies indicated that the most important aspects of quality of life to people were health, education, welfare and the cost of living.[12] Additionally, the countries with the perception of high-quality public services, specifically Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands, scored the highest on levels of happiness.[12] Conversely, Bulgaria, Romania, Lithuania and Italy, who scored low on levels of satisfaction of social services, had low levels of happiness, with some sociologists arguing this indicates there is a strong correlation between happiness and social services.[12]

Poverty

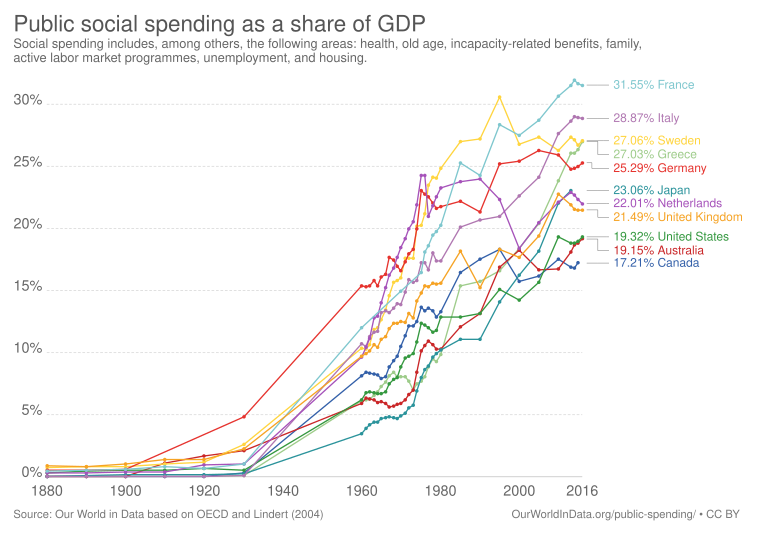

[edit]Research indicates that welfare programs, which are included as a part of social services, have a considerable impact upon poverty rates in countries in which welfare expenditure accounts for over 20% of their GDP.[13][14]

However, the impact of social service programs on poverty varies depending on the service.[15] One paper conducted within China indicates that social services in the form of direct financial assistance does not have a positive impact on the reduction of poverty rates.[15] The paper also stated that the provision of public services in the form of medical insurance, health services and hygiene protection have a 'significantly positive' impact upon the reduction of poverty.[15]

| Country | Absolute poverty rate (1960–1991)

(threshold set at 40% of United States median household income)[13] |

Relative poverty rate

(1970–1997)[14] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | |

| 23.7 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 4.8 | |

| 9.2 | 1.7 | 12.4 | 4.0 | |

| 22.1 | 7.3 | 18.5 | 11.5 | |

| 11.9 | 3.7 | 12.4 | 3.1 | |

| 26.4 | 5.9 | 17.4 | 4.8 | |

| 15.2 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 5.1 | |

| 12.5 | 3.8 | 10.9 | 9.1 | |

| 22.5 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 11.9 | |

| 36.1 | 9.8 | 21.8 | 6.1 | |

| 26.8 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 4.1 | |

| 23.3 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 9.2 | |

| 16.8 | 8.7 | 16.4 | 8.2 | |

| 21.0 | 11.7 | 17.2 | 15.1 | |

| 30.7 | 14.3 | 19.7 | 9.1 | |

Expenditure on social welfare programs

[edit]The table below displays the welfare spending of countries as a percentage of their total GDP. The statistics are sourced from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.[6]

| Rank | Country | 2019 | 2016 | 2010 | 2005 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31.2 | 31.5 | 30.7 | 28.7 | 27.5 | |

| 2 | 28.9 | 29.0 | 28.3 | 25.3 | 23.5 | |

| 3 | 28.7 | 30.8 | 27.4 | 23.9 | 22.6 | |

| 4 | 28.0 | 28.7 | 28.9 | 25.2 | 23.8 | |

| 5 | 15.9 | 28.9 | 27.6 | 24.1 | 22.6 | |

| 6 | 26.6 | 27.8 | 27.6 | 25.9 | 25.5 | |

| 7 | 26.1 | 27.1 | 26.3 | 27.4 | 26.8 | |

| 8 | 25.1 | 25.3 | 25.9 | 26.3 | 25.4 | |

| 9 | 25.0 | 25.1 | 21.9 | 20.7 | 20.4 | |

| 10 | 23.7 | 24.6 | 25.8 | 20.4 | 19.5 | |

| 11 | 23.5 | 27.0 | 23.8 | 20.4 | 18.4 | |

| 12 | 22.6 | 24.1 | 24.5 | 22.3 | 18.5 | |

| 13 | 22.4 | 21.8 | 22.9 | 22.4 | 18.6 | |

| 14 | 30 | 20.7 | 20.0 | 19.4 | ||

| 15 | 21.9 | |||||

| 16 | 21.2 | 22.8 | 23.4 | 21.4 | 22.4 | |

| 17 | 21.1 | 20.2 | 20.6 | 20.9 | 20.2 | |

| 18 | 20.6 | 21.5 | 22.8 | 19.4 | 17.7 | |

| 19 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 23.0 | 21.9 | 20.1 | |

| 20 | 18.9 | |||||

| 21 | 18.7 | 19.4 | 19.8 | 18.1 | 18.0 | |

| 22 | 18.7 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 15.6 | 14.3 | |

| 23 | 18.4 | 17.4 | 18.3 | 13.0 | 13.8 | |

| 24 | 17.8 | 19.1 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 18.2 | |

| 25 | 17.3 | |||||

| 26 | 17.0 | 18.6 | 18.1 | 15.8 | 17.6 | |

| 27 | 16.7 | 22.0 | 22.1 | 20.5 | 18.4 | |

| 28 | 16.2 | 14.5 | 18.7 | 12.2 | 14.8 | |

| 29 | 16.2 | |||||

| 30 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 16.0 | 16.3 | 17.0 | |

| 31 | 16.0 | 19.7 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 16.3 | |

| 32 | 16.0 | 15.2 | 17.0 | 15.9 | 14.6 | |

| 33 | 14.4 | 16.1 | 22.4 | 14.9 | 12.6 | |

| 34 | 12.5 | |||||

| 35 | 11.1 | 10.4 | 8.3 | 6.1 | 4.5 | |

| 36 | 10.9 |

Health services

[edit]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the provision of health services is a significant factor in ensuring that individuals are able to maintain their health and wellbeing.[19] The WHO identifies 16 health services that must be provided by countries to ensure that universal health coverage is achieved.[19] These are classified under four categories: reproductive, maternal and children health services, infectious diseases, 'noncommunicable' diseases, and basic access to medical services.[19] OECD data reveals that the provision of universal health coverage leads to significantly positive outcomes on society.[20] This includes a positive correlation between life expectancy and the provision of health services and a negative relationship between life expectancy and countries which's social service programs do not provide universal healthcare coverage.[20] Additionally, the density of the provision of healthcare services by the government is positively associated with increases in life expectancy.[20]

Children

[edit]

Within the area of child welfare, social services aim to provide help to children and their families, while providing mechanisms to ensure they are able to live safe, stable lives with a permanent home.[22] In the United States, 3 million children are maltreated each year, with the overall economic costs of child maltreatment totalling up to US$80 billion annually.[22] Social service programs cost the US$29 billion USD on child maltreatment prevention and child welfare services.[22] According to researchers, social service programs are effective in reducing maltreatment and reducing overall economic costs to society, however the effectiveness of these programs are significantly reduced when they are not correctly implemented, or when these programs are not implemented together.[22] The issues in which social services attempt at preventing for children include substance abuse, underemployment and unemployment, homelessness and criminal convictions.[22] Social service programs within this area include family preservation, kinship care, foster and residential care.[22]

Women

[edit]Empirical evidence suggests that social service programs have had a significant impact upon the employment of single mothers.[23] Following 1996 welfare reform in the US, employment rates among single mothers have increased considerably from 60% in 1994 to 72% in 1999.[23] Social services, particularly education, are considered by UNICEF as an effective method through which to combat gender inequality.[24] Social services such as education may be employed to overcome discrimination and challenge gender norms.[24] Social services, notably educational programs and aid provided by organisations such as UNICEF, are also essential in providing women strategies and tools to prevent and respond to domestic and family violence.[25] Other examples of social services which may help address this issue include the police, welfare services, counselling, legal aid and healthcare.[26][better source needed]

Social services and COVID-19

[edit]Social services have played a central role in the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[27] Healthcare workers, public officials, teachers, social welfare officers and other public servants have provided critical services in containing the pandemic and ensuring society functions.[27] The impact of the pandemic was compounded by the shortage of social services globally, with the world requiring six million more nurses and midwives to achieve the goals set within the Sustainable Development Goals at the time of the outbreak.[27] Social services, such as education, have been required to adapt to changing social conditions while still providing essential services.[27] Social services have expanded worldwide through the introduction of economic stimulus packages, with governments globally committing US$130 Billion as of June 2020 to manage the pandemic.[27]

See also

[edit]- Australian referendum, 1946 (Social Services)

- Child Protective Services (US)

- Department of Social Services (US)

- Department for Communities and Local Government (UK)

- Emergency Social Services

- Human services

- International Social Services

- Ministry of Community and Social Services (Ontario)

- New York State Social Services Department

- Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government (UK)

- Social Welfare (constituency)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Munday, Brian (2003). European social services: A map of characteristics and trends (DOC) (Report). Council of Europe. Also available as machine-converted HTML.

- ^ a b c Seekings, Jeremy; Nattrass, Nicoli (2015). "The Welfare State, Public Services and the 'Social Wage'". Developmental Pathways to Poverty Reduction. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 162–184. doi:10.1057/9781137452696_7. ISBN 978-1-349-56904-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pierson, Chris (2004). "'Late Industrializers' and the Development of the Welfare State". Social Policy in a Development Context. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 215–245. doi:10.1057/9780230523975_10. ISBN 978-1-4039-3661-5.

- ^ a b c d e Pinker, Robert A. (1998). "Social service". In David Hoibert (ed.). The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (15 ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Incorporated. pp. 375–378. ISBN 978-0-85229-663-9. OCLC 37790903. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Peng, Ito; Wong, Joseph (15 July 2010). "East Asia". In Castles, Francis G.; Leibfried, Stephan; Lewis, Jane; Obinger, Herbert; Pierson, Christopher (eds.). The Oxford handbook of the welfare state. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press. pp. 656–670. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199579396.003.0045. ISBN 978-0-19-957939-6. OCLC 548626400.

- ^ a b OECD. "Social Expenditure Database (SOCX)". Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ a b Le Grand, Julian (25 August 2020). The strategy of equality: Redistribution and the social services. Milton: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-59765-5. OCLC 1124357973.

- ^ a b c d e Flora, Peter (2017-07-28). Flora, Peter; Heidenheimer, Arnold J (eds.). The Development of Welfare States in Europe and America. doi:10.4324/9781351304924. ISBN 978-1-351-30492-4.

- ^ a b c d "The 1833 Factory Act". www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b c d Grandner, Margarete (January 1996). "Conservative Social Politics in Austria, 1880–1890". Austrian History Yearbook. 27: 77–107. doi:10.1017/s006723780000583x. ISSN 0067-2378. S2CID 143805293.

- ^ Whitepaper (Report). Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2022. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ a b c d e Dimian, Gina (2012). "Public Services – Key Factor to Quality of Life". Management & Marketing Challenges for the Knowledge Society. 7: 151–164.

- ^ a b c Kenworthy, L. (1999-03-01). "Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment". Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–1139. doi:10.1093/sf/77.3.1119. hdl:10419/160860. ISSN 0037-7732.

- ^ a b c Moller, Stephanie; Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D.; Bradley, David; Nielsen, Francois (February 2003). "Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (1): 22. doi:10.2307/3088901. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 3088901.

- ^ a b c Chen, Sixia; Li, Jianjun; Lu, Shengfeng; Xiong, Bo (2017-06-05). "Escaping from poverty trap: a choice between government transfer payments and public services". Global Health Research and Policy. 2 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/s41256-017-0035-x. ISSN 2397-0642. PMC 5683608. PMID 29202083.

- ^ Woolard, Ingrid; Harttgen, Kenneth; Klasen, Stephan (August 2010). The evolution and impact of social security in South Africa (Unpublished manuscript). ResearchGate:242595464.

- ^ "Government spending climbs to R1,71 trillion" (Press release). Statistics South Africa. 26 November 2019. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ OECD Data. Health resources – Health spending. doi:10.1787/8643de7e-en. 2 bar charts: For both: From bottom menus: Countries menu > choose OECD. Check box for "latest data available". Perspectives menu > Check box to "compare variables". Then check the boxes for government/compulsory, voluntary, and total. Click top tab for chart (bar chart). For GDP chart choose "% of GDP" from bottom menu. For per capita chart choose "US dollars/per capita". Click fullscreen button above chart. Click "print screen" key. Click top tab for table, to see data.

- ^ a b c "Universal health coverage (UHC)". www.who.int. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b c Pearson, Mark; Colombo, Francesca; Murakami, Yuki; James, Chris (22 July 2016). Universal health coverage and health outcomes (PDF) (Report). OECD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2017.

- ^ Roser, Max (May 26, 2017). "Link between health spending and life expectancy: US is an outlier". Our World in Data. Click the sources tab under the chart for info on the countries, healthcare expenditures, and data sources. See the later version of the chart here.

- ^ a b c d e f Ringel, Jeanne S.; Schultz, Dana; Mendelsohn, Joshua; Holliday, Stephanie Brooks; Sieck, Katharine; Edochie, Ifeanyi; Davis, Lauren (2018-03-30). "Improving Child Welfare Outcomes". Rand Health Quarterly. 7 (4): 4. ISSN 2162-8254. PMC 6075810. PMID 30083416.

- ^ a b Moffitt, Robert A. (2 January 2002). "From Welfare to Work: What the Evidence Shows". Brookings. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b "Gender equality". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ Ziaziaris, Simone (5 August 2019). "Turning domestic violence into triumph". Sydney: UNICEF Australia. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06.

- ^ "Police, legal help, and the law". Family & Community Services. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b c d e "The role of public service and public servants during the COVID-19 pandemic | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org. 2020-06-11. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

External links

[edit]- In Chelsea, coalition aims to save lives on verge of unraveling – article on "Hub model" of social service coordination

Social services

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Objectives and Scope

Social services primarily seek to address vulnerabilities arising from economic hardship, disability, family disruption, or other circumstances that impair individuals' or families' ability to meet basic needs, with core objectives centered on fostering economic self-sufficiency, protecting against neglect or abuse, and minimizing long-term dependency on state support. In the United States, for instance, federal guidelines under the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) emphasize services that prevent or remedy exploitation of children and adults unable to self-protect, rehabilitate or reunite families, reduce reliance on institutional care through community-based alternatives, and equip recipients with skills to better access resources.[11] These aims reflect a causal focus on interrupting cycles of poverty and dysfunction rather than indefinite provision, though implementation varies by jurisdiction and often prioritizes immediate relief over proven long-term independence metrics.[12] The scope of social services extends beyond mere financial aid to encompass preventive, rehabilitative, and supportive interventions tailored to at-risk populations, including children, the elderly, disabled persons, and low-income households. This includes case management, counseling, home-based care, and training programs designed to enhance personal agency and family stability, excluding universal entitlements like broad healthcare or education systems.[13] Internationally, frameworks such as those from the International Federation of Social Workers define the profession's mandate as promoting social cohesion and empowerment, but empirical critiques highlight that expansive scopes can inadvertently expand bureaucracies without commensurate reductions in client needs, as evidenced by persistent welfare rolls in high-spending nations despite stated self-sufficiency goals.[14] Delivery models typically involve public agencies coordinating with nonprofits, with eligibility determined by means-testing or risk assessments to target those demonstrably unable to self-provision, ensuring resources align with verifiable deprivations rather than broad equity ideals.[15]Providers, Eligibility, and Delivery Models

Social services are predominantly provided by government agencies at national, regional, and local levels, which fund and oversee programs through public budgets derived from taxation and social insurance contributions.[16] In many OECD countries, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including charitable nonprofits classified under tax-exempt categories such as 501(c)(3) in the United States, deliver services under government contracts, handling areas like child welfare, elder care, and community support to leverage specialized expertise and local knowledge.[17] Private for-profit entities participate in delivery through public-private partnerships, particularly in long-term care and vocational training, where they compete for contracts based on performance metrics, though their role remains secondary to public and nonprofit providers due to accountability concerns over profit motives in essential services.[18] Eligibility for social services typically hinges on means-testing, which assesses an applicant's income, assets, and household resources against predefined thresholds to ensure aid targets those deemed financially needy, as seen in programs like minimum-income benefits across OECD nations where eligibility requires non-welfare income below a specified level, often adjusted for family size and regional cost-of-living variations.[19][20] Categorical criteria, such as age, disability status, unemployment duration, or family circumstances (e.g., single parenthood or child protection risks), supplement means-testing in targeted programs, while universal models—applied to services like child allowances in countries including Canada and Sweden—extend benefits to all qualifying residents irrespective of income to minimize administrative barriers and stigma.[16] Residence requirements, citizenship or legal status, and behavioral conditions (e.g., job search mandates) further delineate eligibility, with OECD data indicating that as of 2021, most countries impose asset limits alongside income tests to prevent accumulation that could undermine program sustainability.[21] Delivery models vary between cash transfers, which provide recipients with unrestricted funds for flexible use, and in-kind provisions such as food vouchers, housing subsidies, or direct services like home-delivered meals, the latter ensuring benefits address specific needs but potentially reducing recipient autonomy.[22] Public administration dominates core delivery in centralized systems, but subcontracting to nonprofits and private providers is widespread, as evidenced by U.S. welfare reforms since 1996 that shifted foster care and day care to contracted entities, enabling scale while imposing outcome-based oversight.[17] Decentralized models in federal states like Germany and the United States allocate responsibilities to subnational governments for tailored implementation, whereas hybrid voucher systems in nations including the Netherlands allow beneficiaries to select providers, fostering competition and choice amid public funding.[18] OECD analyses highlight ongoing shifts toward digital platforms for streamlined delivery, reducing fraud through data-linked verification while maintaining a mix of contributory (insurance-based) and non-contributory (tax-funded) streams.[16]Historical Development

Pre-Modern Roots and Early Charity Systems

In ancient civilizations, rudimentary systems of public assistance emerged alongside private philanthropy, often tied to maintaining social order rather than comprehensive welfare. The Roman Republic initiated grain distributions (frumentationes) as early as 123 BCE under Gaius Gracchus, providing subsidized or free grain to approximately 200,000 eligible male citizens in Rome—about one-fifth of the urban population—to avert famine-induced riots and secure political loyalty.[23] This evolved into the formalized annona under Emperor Augustus around 28 BCE, incorporating the alimenta program to support poor children with monthly stipends and food rations, funded by imperial estates and taxes on provinces like Egypt.[24] These measures prioritized urban plebeians over rural or non-citizen poor, reflecting a pragmatic state mechanism rather than universal charity, with distribution points (horrea) ensuring controlled access amid logistical challenges like grain storage and transport.[25] Religious traditions independently institutionalized charity as a moral imperative, predating and influencing state systems. In Judaism, tzedakah—rooted in Torah commandments from circa 1200 BCE—mandated communal support for the impoverished through practices like leaving harvest gleanings, corner fields, and tithes for the poor, as well as prohibiting usury among Jews and requiring debt remission every seventh year.[26] This framed aid not merely as benevolence but as justice (tzedek), obligating even the poor to contribute minimally, with rabbinic texts from the 2nd century CE expanding it to include anonymous giving and employment assistance to preserve dignity.[27] Similarly, in Islam, zakat was enshrined as the third pillar of faith shortly after 622 CE in Medina, requiring able Muslims to donate 2.5% of qualifying wealth (e.g., savings exceeding the nisab threshold for one lunar year) to eight categories of recipients, including the destitute, debtors, and wayfarers, collected and distributed by community or state authorities to purify assets and foster equity.[28] Early Christianity adapted Jewish almsgiving traditions, emphasizing systematic relief from the apostolic era. New Testament directives, such as those in Acts 4:32-35, describe communal collections for widows and the needy, with deacons appointed by the late 1st century CE to oversee distributions in urban churches like those in Corinth and Jerusalem.[29] By the medieval period (circa 500-1500 CE), the Catholic Church expanded this into Europe-wide networks of monasteries, hospices, and bishoprics providing food, shelter, and rudimentary medical care to transients, orphans, and the infirm, often funded by tithes and bequests; for instance, Benedictine rules from 529 CE required monks to allocate resources for local poor relief.[24] These efforts distinguished between the "voluntary poor" (e.g., ascetics seeking spiritual merit) and involuntary destitute, viewing alms as a sacramental act benefiting the donor's soul while addressing immediate needs, though limited by feudal economies and episodic famines.[30]19th-Century Industrial Era Reforms

The rapid industrialization of Britain in the early 19th century, characterized by factory expansion and urban migration, intensified social problems including widespread child labor, pauperism, and epidemic diseases in overcrowded slums, prompting legislative responses to mitigate these conditions.[31] The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 reformed the Elizabethan-era system by consolidating administration under centralized Poor Law Unions and constructing workhouses, where able-bodied paupers performed labor for minimal sustenance to discourage dependency and curb rising relief costs that had reached £8 million annually by 1833.[32][31] This utilitarian approach separated families in workhouses and provided rudimentary education to pauper children, reflecting a philosophy that relief should be less desirable than the lowest-paid work to incentivize self-reliance.[32] Subsequent Factory Acts addressed exploitative labor practices; the 1833 Act banned employment of children under age nine in cotton and woollen mills, restricted those aged 9–13 to nine hours daily, and mandated four hours of schooling, enforced by the first factory inspectors.[33][34] Building on this, the 1844 Factory Act extended regulations to women and required safety fencing around machinery, while the 1847 Ten Hours Act capped workdays at ten hours for women and children, driven by evidence of health deterioration from 12–16-hour shifts.[31] Public health reforms followed Edwin Chadwick's 1842 Sanitary Report, which documented average life expectancy at 26 years in industrial towns due to contaminated water and sewage, estimating preventable diseases cost £1–2 million yearly in lost productivity and relief.[35] The Public Health Act of 1848 established a General Board of Health under Chadwick to survey districts with mortality over 23 per 1,000 and empower local boards for sewerage, drainage, and clean water provision, prioritizing economic efficiency by reducing pauperism through disease prevention.[35] Across continental Europe, industrialization spurred analogous measures, such as France's 1841 child labor law limiting work to eight hours for those under eight and Germany's emerging mutual aid societies, evolving from voluntary charity toward state-coordinated assistance for urban poor families.[36] These reforms represented pragmatic state encroachments into social welfare, grounded in empirical observations of industrial causation—overwork, filth, and destitution—rather than abstract entitlements, laying foundations for modern social services while prioritizing cost control and labor discipline.[31]20th-Century State Expansion and Welfare States

The expansion of state involvement in social services accelerated in the early 20th century amid economic upheavals, including World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II, which exposed vulnerabilities in private charity and market-based support systems.[37] Governments increasingly assumed responsibility for mitigating poverty, unemployment, and health risks through systematic public programs, shifting from ad hoc relief to institutionalized entitlements funded by taxation and contributions.[38] By mid-century, this led to the formation of comprehensive welfare states in Western nations, where social services encompassed income support, healthcare, and family assistance, often justified as essential for social stability and economic recovery.[39] In the United States, the Great Depression prompted the New Deal under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, initiated in 1933, which introduced federal social services to address mass unemployment reaching 25% by 1933.[40] Key legislation included the Social Security Act of August 14, 1935, establishing old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and aid for dependent children, marking the federal government's entry into direct welfare provision previously handled by states and localities.[41] These programs expanded state expenditure on social services from minimal pre-Depression levels to a foundational safety net, though coverage initially excluded many agricultural and domestic workers.[42] Post-World War II Europe saw rapid welfare state consolidation, driven by wartime destruction and commitments to reconstruction. In the United Kingdom, the 1942 Beveridge Report, published November 1942, proposed a unified social insurance system to combat "five giants" of want, disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness, influencing the 1945 Labour government's reforms.[43] Implementation followed with the National Insurance Act 1946 and National Health Service Act 1946, effective July 5, 1948, providing universal healthcare and benefits, which increased public social spending from 4.7% of GDP in 1913 to over 10% by 1937 and further post-war.[44] [45] Scandinavian countries developed distinctive universalist models in the 1930s, building on earlier reforms, with Sweden's Social Democratic "People's Home" (folkhemmet) policy from 1932 emphasizing full employment and family support.[46] Norway realized cradle-to-grave security between 1945 and 1970 through national insurance and healthcare expansions, funded by progressive taxes, achieving low inequality via comprehensive coverage for all citizens regardless of income.[47] By 1960, developed nations universally adopted core welfare institutions, with Western Europe's mid-20th-century growth linked to labor mobilization, economic booms, and ideological consensus on state intervention.[38] This era's expansions often prioritized empirical needs over ideological purity, though academic analyses note influences from pre-war experiments and wartime planning.[48]Post-1980s Reforms and Contemporary Shifts

In the 1980s, neoliberal policies influenced reforms across Western nations, emphasizing market mechanisms, reduced public spending, and work incentives over expansive welfare entitlements. In the United States, the Reagan administration curtailed federal welfare programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), converting some into block grants to states and promoting private sector involvement, which slowed the growth of social expenditures amid stagflation and rising deficits.[49] These changes reflected a causal shift from viewing poverty as structural to emphasizing individual responsibility, with empirical data showing stabilized caseloads despite economic pressures.[50] The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act marked a pivotal U.S. reform, replacing AFDC with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which imposed five-year lifetime limits, work requirements for recipients, and greater state flexibility in administration. Caseloads declined by over 60% from 1996 to 2000, coinciding with employment gains among single mothers—rising from 60% to 75%—and a drop in child poverty from 20.5% in 1996 to 16.2% by 2000, attributable in part to the strong economy but also to reform-induced labor force entry.[51][52][53] Critics noted persistent deep poverty in recessions, yet longitudinal studies confirm sustained reductions in welfare dependence without broad increases in extreme deprivation when controlling for economic cycles.[54][55] In the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher's governments from 1979 to 1990 pursued similar retrenchment, privatizing state assets and tightening eligibility for benefits like unemployment insurance, followed by New Labour's 1997-2010 emphasis on "workfare" through programs like the New Deal, which mandated job searches and training. This shifted the welfare regime toward a Schumpeterian model prioritizing competitiveness, with unemployment benefit recipiency falling from 2.5 million in 1980 to under 1.5 million by 2000.[56][57] European countries adopted "activation" strategies post-1980s, increasing obligations for job-seeking while preserving core safety nets; across 16 nations from 1980 to 2015, policies balanced punitive elements (e.g., sanctions) with enabling supports (e.g., training), correlating with higher employment rates among benefit claimants but varied retrenchment based on institutional path dependence.[58] Post-2008 financial crisis austerity measures in Europe, particularly in the UK and southern states, further constrained social services, with public expenditure cuts averaging 5-10% in welfare budgets from 2010-2015, prompting recalibrations like means-testing pensions and conditional cash transfers to sustain fiscal viability amid slow growth.[59] Aging populations exacerbated pressures, as dependency ratios rose—e.g., from 25% in 1990 to over 35% by 2020 in OECD countries—forcing reforms like raising retirement ages and shifting elderly care toward community-based models to manage long-term support costs projected to double by 2050.[60] The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily reversed retrenchment trends, with governments expanding benefits—U.S. stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment insurance reached 80% wage replacement for many—and bolstering elderly services, yet it exposed vulnerabilities like workforce shortages in long-term care and digital exclusion for older recipients. Post-2020, debates center on sustainability, with empirical reviews indicating that activation-oriented reforms from the 1980s onward improved self-sufficiency metrics without collapsing safety nets, though demographic shifts and inequality demand evidence-based adjustments beyond ideological defaults.[61][62][63]Types of Social Services

Income Maintenance and Cash Assistance

Income maintenance encompasses government-administered programs that deliver direct cash payments to low-income individuals or families to sustain a basic standard of living and mitigate the risk of extreme poverty. These initiatives, often termed cash assistance or social assistance, operate primarily through means-tested eligibility, where benefits are calibrated to income, assets, and household size, aiming to bridge gaps between earnings and subsistence needs.[64][65] Unlike contributory social insurance schemes, such as retirement pensions funded by prior payroll taxes, income maintenance relies on general taxation and targets non-workers or those with insufficient earnings, including the unemployed, disabled, or single-parent households.[66] In the United States, key examples include Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which provides monthly federal payments averaging $698 to 7.4 million recipients as of January 2024, primarily elderly, blind, or disabled individuals with incomes below federal thresholds.[67] Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), established under the 1996 welfare reform, offers time-limited cash aid to low-income families with children, emphasizing work participation; in fiscal year 2023, states reported serving about 1.1 million families amid stricter eligibility and diversion to job training.[68] Unemployment insurance, a quasi-cash program, disbursed over $20 billion in benefits during low-claim periods in 2023, replacing roughly 40-50% of prior wages for eligible involuntarily unemployed workers meeting state-specific duration and job-search criteria.[69] These programs collectively reached tens of millions, with public assistance income reported by 18.7% of U.S. households in 2022 Census data, though caseloads have declined since peaks in the 1990s due to economic growth and policy shifts toward self-sufficiency mandates.[70] Globally, cash assistance varies by development level but shares a focus on targeted transfers; the World Bank's ASPIRE database tracks over 1,800 such programs across 130+ countries, with non-contributory cash schemes comprising 25% of safety nets in high-income nations and emphasizing vulnerability over universal coverage.[65] In OECD countries, means-tested benefits like Germany's Bürgergeld (introduced 2023, replacing Hartz IV) provide €502 monthly for singles, conditional on active job-seeking, serving about 5.5 million recipients in 2024. Developing economies often deploy conditional cash transfers, such as Brazil's Bolsa Família (reaching 14.6 million families in 2023 with averages of R$600), linking payments to school attendance and health checkups to foster human capital alongside immediate relief.[71] Delivery models include electronic transfers for efficiency, reducing administrative costs by up to 30% compared to in-kind aid, though fraud risks and dependency concerns persist.[72] Empirical evaluations reveal cash assistance effectively lowers absolute poverty rates by supplementing deficient incomes, as evidenced by pre- and post-implementation data in multiple jurisdictions showing drops from 20-30% to under 10% in extreme deprivation metrics.[71] However, randomized trials like the 1970s Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment demonstrated modest labor supply reductions—about 5-10% in hours worked, mainly among wives—suggesting potential trade-offs between income support and workforce participation, with no significant boosts to overall family earnings.[73] Systematic reviews of basic income analogs confirm short-term poverty alleviation but mixed long-term outcomes on employment and health, underscoring the need for work incentives to avoid disincentivizing self-reliance.[74] Program efficacy hinges on design: unconditional transfers excel in crisis response, as in Colombia's 2020 emergency aid which boosted household consumption by 15-20% without crowding out private spending, yet sustained versions risk fiscal strain, with U.S. TANF expenditures stabilizing at $16.5 billion federally in 2023 amid debates over block grant adequacy.[75][76]Health and Disability Support

Health and disability support within social services encompasses government-funded programs providing medical care, income replacement, rehabilitation, and assistive services to individuals with physical, mental, or developmental impairments, as well as low-income populations facing health barriers. These services aim to mitigate functional limitations and prevent destitution, often through means-tested eligibility or disability determinations based on medical evidence of inability to work. In the United States, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) awards benefits to workers with sufficient earnings history who meet strict criteria, with final award rates averaging 30% for claims filed from 2012 to 2021.[77] Similar systems exist internationally, such as contributory disability pensions in Europe, which replace lost earnings but vary in generosity and stringency. Empirical evidence indicates these programs yield measurable health and financial benefits. Receipt of SSDI payments has been associated with reduced mortality rates, particularly among lower-income beneficiaries, by alleviating financial stress and enabling access to care.[78] Disability insurance confers substantial welfare gains to recipients and third parties, improving financial outcomes like reduced distress and increased stability, though spillover effects depend on program design.[79] Vocational rehabilitation initiatives, which pair benefits with employment support, assist approximately one million people with disabilities annually in transitioning from public support to work in the U.S., though overall employment rates remain low.[80] Despite these gains, persistent inequities undermine effectiveness. Persons with disabilities experience elevated mortality, morbidity, and functional limitations compared to the general population, often due to barriers in service access and systemic gaps in data collection.[81] Public health insurance for low-income groups, such as Medicaid expansions, shields households from catastrophic costs and reduces poverty, with long-term effects on child health outcomes.[82] However, work incentive structures in disability programs can influence labor participation; reforms replacing abrupt benefit cliffs with gradual phase-outs have encouraged higher earnings without full benefit loss, suggesting causal links between policy design and behavioral responses.[83] Challenges include low approval rates and unmet needs, which limit reach. In low- and middle-income countries, interventions like assistive devices and community-based rehabilitation show variable effectiveness in improving participation, but evidence gaps persist for scalable models.[84] State-level expansions of personal assistance services have reduced hospital utilization for conditions like hypertension among disabled individuals, highlighting targeted supports' role in cost containment.[85] Overall, while these services address immediate needs, their long-term success hinges on integrating health support with employment incentives to counter potential dependency, as mixed results from disability employment services indicate only modest reductions in public benefit reliance.[86]Child Protection and Family Services

Child protection and family services refer to state-administered programs that investigate reports of child abuse or neglect, provide immediate responses to ensure child safety, and deliver interventions such as family preservation, foster care placement, or permanency planning through adoption or guardianship when children cannot safely remain with their parents.[87] [88] These services encompass screening referrals, conducting assessments of maltreatment risks, and coordinating with courts for removals or supervised services, with the dual aims of safeguarding children from harm and strengthening family capacities where possible.[89] In practice, processes begin with mandatory reporting from professionals like teachers or physicians, followed by investigations that may involve home visits, interviews, and evidence gathering to substantiate allegations of physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional maltreatment, or neglect.[90] In the United States, child protective services handle millions of referrals annually; for federal fiscal year 2023, an estimated 3,081,715 children were subjects of reports to state agencies, with agencies screening in approximately 2.1 million for formal investigations or alternative responses.[91] [92] Of substantiated cases, around 437,000 children entered foster care in recent years, often due to neglect comprising over 75% of findings, while physical abuse accounts for about 17% and sexual abuse 11%.[93] Post-intervention monitoring reveals recurrence risks, with 17% of confirmed victims experiencing maltreatment again within 60 months, influenced by factors like parental substance abuse or prior history.[94] Interventions include in-home services like parenting training to prevent removal, but when safety thresholds are unmet, children are placed in foster homes, kinship care, or group settings, with federal policy prioritizing least restrictive permanency options.[95] Empirical studies on effectiveness show mixed results; while some evidence indicates foster care placement can mitigate immediate risks for severely maltreated children, leading to improved short-term outcomes in health and behavior compared to remaining in high-risk homes, long-term data reveal persistent challenges including elevated rates of mental health issues and educational disruptions among former foster youth.[96] [97] Kinship placements yield better adult outcomes, such as higher employment and education attainment, than non-relative foster care.[98] However, evidence-based programs like behavioral parent training have demonstrated reductions in recurrence for targeted families, though overall system-wide impacts on preventing maltreatment remain limited, with no consistent causal link to broad declines in abuse rates.[99][100] Criticisms highlight that investigations and separations often inflict trauma equivalent to or exceeding the original maltreatment, with separated children experiencing heightened stress, attachment disruptions, and lifelong psychosocial deficits, particularly when poverty—rather than intentional harm—is misclassified as neglect.[101] [102] Family policing practices can exacerbate racial disparities, as Black and Native American children face higher removal rates despite similar maltreatment substantiations, and even unsubstantiated probes correlate with school exclusions and family distress.[103] Recurrence persists due to unaddressed root causes like economic instability, suggesting interventions favor removal over upstream supports, with studies questioning whether the net benefit of state custody outweighs harms in non-severe cases.[104] [105]Elderly Care and Long-Term Support

Elderly care and long-term support encompass social services designed to assist older adults with daily activities, medical needs, and independence preservation amid functional decline. These services include institutional care in nursing homes, community-based options like home health aides, and programs such as Meals on Wheels for nutritional support. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals reaching age 65 will develop severe long-term services and supports (LTSS) needs before death, with 48% receiving paid care.[106] Globally, over half of adults post-65 develop serious disabilities requiring such aid.[107] Delivery models vary by country, with a shift toward community-based care to reduce institutionalization costs and improve quality of life. In OECD nations, about half of long-term care (LTC) occurs in home or community settings, though institutional beds dominate in countries like Japan and Korea.[108] Public funding covers roughly 80% of LTC expenditures across OECD countries, often through social insurance or means-tested benefits.[109] High spenders like the Netherlands allocate 4.4% of GDP to LTC as of 2021, compared to the OECD average of 1.8%, reflecting generous universal coverage but straining budgets amid aging demographics.[110] Staffing shortages pose significant challenges, exacerbated by an aging workforce and low wages in care sectors. In the U.S., 94% of nursing homes reported shortages in 2023, with 75% noting worsening conditions since 2020, leading to burnout, reduced care quality, and reliance on overtime or agency staff.[111] Unmet LTSS needs correlate with poorer physical and mental health outcomes, including higher suicide ideation rates among the elderly.[112] Rapid population aging—projected to double the over-80 population in many OECD countries by 2050—intensifies demand, outpacing supply and increasing wait times for services.[113] Empirical evidence indicates LTSS reduces elderly poverty and supports health stability, though causal links to broader outcomes like dependency or fiscal sustainability remain debated. Social Security and related transfers in the U.S. lifted over 27 million from poverty in 2018, disproportionately benefiting seniors.[114] Community-based services improve mental health by alleviating depression, yet institutional care shows mixed results on physical outcomes due to infection risks and isolation.[115] High public spending correlates with lower out-of-pocket costs but raises concerns over long-term affordability, as LTC expenditures as a GDP share rose in most OECD countries from 2018 to 2021.[116] Reforms emphasizing family or private involvement, as in some Asian systems, may mitigate fiscal pressures but risk uneven access.[117]Housing, Homelessness, and Basic Needs Aid

Social services addressing housing, homelessness, and basic needs encompass government-funded programs providing rental subsidies, public housing units, emergency shelters, and assistance for food, utilities, and other essentials to low-income individuals and families. In the United States, key housing programs include the Housing Choice Voucher Program (Section 8), which subsidizes private-market rents for eligible households, and public housing developments managed by local housing authorities. These initiatives aim to prevent eviction and stabilize living situations, with voucher recipients experiencing significantly lower rates of housing insecurity and homelessness compared to non-recipients.[118][119] However, demand far exceeds supply; as of 2023, only about one in four eligible households receives rental assistance due to funding caps.[120] Homelessness aid often prioritizes immediate shelter and supportive services, with the "Housing First" model—offering permanent housing without preconditions like sobriety—demonstrating empirical success in reducing time spent homeless and improving retention rates. Randomized trials indicate Housing First accelerates exits from homelessness by up to 88% relative to treatment-first approaches and enhances stability over two years, though effects on broader health outcomes like substance use reduction remain inconsistent across studies.[121][122][123] The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's 2024 Point-in-Time count recorded 771,480 people experiencing homelessness on a single night in January, an 18% rise from 2023, driven partly by housing shortages but also correlated with high rates of co-occurring mental illness (affecting about 75% of the homeless population in high-income countries) and substance dependence (38% alcohol-dependent, 26% other drugs).[124][125][126] Empirical analyses underscore that addiction and untreated mental health issues often precede and perpetuate homelessness, complicating service delivery beyond mere shelter provision.[127][128] Basic needs aid includes the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provided benefits to an average of 41.7 million participants monthly in fiscal year 2024, averaging $99.8 billion in federal spending and linking to reduced food insecurity, poverty, and improved health metrics such as lower healthcare costs.[129][130] SNAP's structure—delivering electronic benefits for food purchases—frees household resources for other essentials like utilities, with studies showing it mitigates material hardships more effectively than cash equivalents in some contexts due to targeted nutritional focus. Complementary programs, such as the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), address utility shutoffs, though coverage remains limited, serving fewer than 10% of eligible households annually. Public housing outcomes reveal mixed results: while it averts immediate homelessness for residents, concentrated poverty in developments has been linked to social challenges, prompting reforms like mixed-income requirements under the 1990s Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act.[131][132] Overall, these services demonstrably curb acute crises but face scalability constraints, with evidence suggesting root-cause interventions for behavioral health yield longer-term reductions in reliance compared to housing alone.[127]Administration and Implementation

Governmental Structures and Oversight

Social services administration typically operates through multi-level governmental structures that balance centralized policy-setting with decentralized delivery to address diverse local needs. At the national level, ministries or departments of social affairs, health, or human services formulate eligibility standards, allocate funding, and enforce regulatory compliance, while subnational entities—such as states, provinces, or municipalities—manage frontline implementation, including caseworker assessments and service distribution. This division reflects federal systems like the United States, where the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) coordinates federal programs but delegates administration to state agencies, resulting in 50 distinct structures varying by alignment of functions like child welfare and income support.[133] [1] In unitary states such as the United Kingdom, oversight centralizes under the Department for Work and Pensions, with local authorities handling execution under national guidelines.[134] Oversight mechanisms emphasize accountability through legislative scrutiny, independent audits, and grievance processes to mitigate fraud, errors, and inefficiencies inherent in fragmented systems. In the U.S., congressional committees like the House Oversight and Accountability Committee review welfare expenditures, while the Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducts evaluations; for instance, HHS's Office of Inspector General performs annual audits detecting billions in improper payments across programs like Medicaid.[135] Internationally, bodies such as supreme audit institutions in OECD countries monitor fiscal integrity, and social protection systems incorporate feedback loops like complaint registries to address eligibility disputes, though implementation varies, with stronger enforcement in nations like Germany via insurance-based parastatal oversight.[136] [137] Fragmentation across agencies—evident in the U.S. where six cabinet departments and five independent agencies oversee 27 cash assistance programs—often complicates coordination and increases administrative costs, as duplicate efforts reduce efficiency without proportional benefits in outcomes.[136] Performance-based oversight, including data-driven metrics on caseloads and outcomes, has gained traction; for example, state human services agencies increasingly use integrated technology platforms for cross-program tracking, though adoption lags due to legacy systems and privacy constraints.[133] In Europe, hybrid models blend public administration with quasi-autonomous non-governmental organizations under ministerial supervision, enabling targeted reforms but exposing vulnerabilities to political shifts in funding priorities.[138]Funding Sources and Expenditure Patterns

Public social services in developed countries are predominantly funded through general government revenues derived from taxation and social insurance contributions paid by employers, employees, and self-employed individuals.[4][139] These sources account for the vast majority of expenditures, with private contributions—such as user fees, philanthropy, or voluntary insurance—playing a supplementary role typically under 20% of total social spending in OECD nations.[140] Social insurance contributions often earmark funds for specific programs like pensions and health, while general taxes support means-tested assistance and family benefits, reflecting a mix of contributory and redistributive financing models.[141] Across OECD countries, public social expenditure averaged approximately 20% of GDP in 2022, rising to over 23% during the 2020 COVID-19 peak before stabilizing, with estimates for 2024 projecting levels around 21% on average.[4][142] Expenditure patterns show significant cross-country variation: continental European nations like France and Finland exceed 30% of GDP, driven by comprehensive pension and health systems, while the United States maintains lower public outlays at around 19% but higher total social spending when including private elements.[143] In the European Union, total social protection benefits reached 26.8% of GDP in 2023, underscoring the sector's dominance in public budgets.[144] The breakdown of social expenditures reveals a heavy emphasis on age-related supports, with old-age and survivor pensions comprising the largest share at 7.7% of GDP on average, followed by health services at 5.8%.[145][143] Other categories include family benefits (2.2%), incapacity-related payments (2.1%), and unemployment support (1.2%), with smaller allocations for housing and active labor market policies.[3]| Category | Average % of GDP (OECD, recent data) |

|---|---|

| Old-age and survivor pensions | 7.7% [145] |

| Health | 5.8% [145] |

| Family benefits | 2.2% [3] |

| Incapacity | 2.1% [3] |

| Unemployment | 1.2% [3] |

| Other (e.g., housing, ALMP) | ~1.0% [3] |

Workforce Dynamics and Professional Standards

The social services workforce, primarily comprising social workers, case managers, and direct support professionals, is characterized by a heavy predominance of women, with approximately 81% female and 19% male in the United States as of recent data.[146] This gender imbalance persists across educational levels, where baccalaureate social work students are 87% female.[147] The total number of social workers in the U.S. reached about 751,900 in 2023, including licensed and unlicensed practitioners across public and private sectors.[148] Educational requirements typically involve a bachelor's or master's degree in social work from accredited programs, with many entering the field through Council on Social Work Education (CSWE)-approved institutions.[149] Workforce dynamics reveal persistent challenges, including acute shortages and high turnover rates exacerbated by burnout. In 2024, 43 of 44 responding U.S. states reported behavioral health workforce shortages, with 37 states indicating deficits in all major categories relevant to social services.[150] Direct support professionals in intellectual and developmental disabilities services experienced an average turnover rate of 43.3%, driven by staffing vacancies that left 95% of organizations facing moderate to severe shortages in the prior year.[151][152] Empirical studies link these issues to occupational stressors, with burnout prevalence among social workers estimated at 20%, including 50% reporting emotional exhaustion, 45% depersonalization, and 39% reduced personal accomplishment.[153] Avoidant coping strategies partially mediate the stress-burnout relationship, contributing to intentions to leave the profession.[154] Professional standards in social services emphasize licensure, ethical guidelines, and competency benchmarks to ensure accountability. In the U.S., licensing is state-regulated through bodies affiliated with the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB), requiring a relevant degree, passage of the ASWB exam, supervised clinical hours (typically 3,000–4,000 for advanced practice), and adherence to moral character standards.[155][156] The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics sets core principles, including service, social justice, dignity, integrity, competence, and the importance of human relationships, serving as a framework for resolving ethical dilemmas in practice.[157] These standards, updated periodically to reflect evolving professional demands, mandate ongoing education and prohibit unlicensed practice in clinical roles, though enforcement varies by jurisdiction and has been critiqued for inconsistencies in addressing workforce shortages.[158] The Social Work Licensure Compact, enacted in some states, facilitates multistate practice for eligible licensed workers, aiming to mitigate mobility barriers amid shortages.[159]Empirical Impacts

Effects on Poverty Alleviation and Inequality

Social services, encompassing cash transfers, in-kind benefits, and targeted aid, have contributed to reductions in absolute poverty rates across developed nations by supplementing low incomes and providing essential goods. Cross-national analyses indicate that more generous welfare provisions correlate with lower absolute poverty thresholds, as measured against fixed standards of material deprivation.[160] [161] For instance, in the United States, the expansion of programs like Supplemental Security Income and food stamps in the 1970s helped lower absolute poverty from approximately 12.3% in 1970 to 11.1% by 1980, though rates later stabilized around 11-13% despite increased spending.[9] In Europe, countries with comprehensive welfare systems, such as those in Scandinavia, exhibit absolute poverty rates below 5% in recent decades, attributable in part to universal child allowances and housing subsidies.[162] However, the effects on relative poverty—defined as income below a percentage of the national median—are less pronounced, with welfare states often reducing but not eliminating disparities tied to market earnings. Studies across 16 OECD nations show that while benefits lower relative poverty risks, particularly for families and the elderly, the overall distribution remains influenced by pre-transfer income gaps, yielding modest net declines of 2-4 percentage points in at-risk populations.[163] [160] Long-term trends in Europe post-2008 financial crisis reveal persistent or rising long-term poverty in 13 of 26 countries despite sustained social expenditures, suggesting diminishing marginal returns from expanded programs.[164] Regarding inequality, social spending in OECD countries systematically narrows post-tax and transfer Gini coefficients, with panel data from 21 nations demonstrating that a 1% increase in social outlays as a share of GDP correlates with a 0.5-1% reduction in inequality measures.[165] [166] Transfers targeted at low earners, such as earned income tax credits, prove more effective than universal schemes in compressing the income ratio between the top and bottom deciles, which averaged 8.4:1 across OECD members in 2021 after redistribution.[167] [168] Yet, empirical scrutiny reveals caveats: behavioral responses, including reduced labor supply among beneficiaries, can offset fiscal redistribution, as evidenced by micro-level studies where in-kind benefits fail to yield net poverty declines due to offsetting income and substitution effects.[9] In high-spending contexts, certain expenditure categories, like unemployment benefits, may inadvertently widen market income inequality by prolonging joblessness.[169] Overall, while social services alleviate immediate hardships and mitigate extreme deprivation, their capacity to durably curb inequality is constrained by underlying economic structures and incentive distortions, with cross-country variations highlighting that targeted, conditional aid outperforms expansive entitlements in sustaining poverty reductions without exacerbating dependency.[160] [170]Influences on Labor Participation and Dependency

Generous means-tested social services often impose high effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) on additional earnings, as benefits phase out with rising income, reducing the net financial incentive to work or increase hours. For low-income households in the United States, combining federal income taxes, state taxes, and benefit reductions from programs like SNAP and Medicaid can yield EMTRs exceeding 100%, meaning recipients may lose more in benefits than they gain in wages, creating "benefit cliffs" that discourage employment transitions.[171][172] Similarly, empirical models indicate that such structures lower labor supply, particularly among single mothers eligible for cash assistance, with pre-1996 U.S. Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) reducing work participation by substituting for market labor.[173] The 1996 U.S. welfare reform, shifting to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) with time limits and work requirements, substantially boosted employment among low-income mothers, increasing labor force participation rates by up to 10 percentage points in affected groups while reducing caseloads by over 60% from 1996 to 2000.[174] Experiments from that era confirmed that mandating work alongside supports like childcare subsidies raised employment without proportional income drops, countering prior dependency patterns where long-term receipt eroded skills and attachment to the workforce.[175] However, persistent high EMTRs in overlapping programs continue to hinder full-time work for some, with studies showing that informing recipients of these incentives via targeted communication can modestly increase job uptake, though effects vary by family structure.[176] Cross-nationally, OECD countries with elevated social spending—averaging 20-30% of GDP in nations like France and Italy—exhibit lower labor force participation among prime-age workers and the elderly compared to lower-spending peers, with social security generosity explaining up to 79% of employment gaps for those aged 55-64.[4][177] In Denmark, expanded youth welfare benefits reduced employment probabilities by 1-2 percentage points, amplifying intergenerational transmission where parental disability insurance uptake raises child reliance by similar margins.[178][179] While targeted transfers like the U.S. Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) can incentivize entry-level work by subsidizing earnings, broader means-tested systems foster dependency cycles, as evidenced by stagnant participation in high-benefit European welfare states despite low official unemployment.[180][181]Outcomes for Health, Education, and Family Stability

Social services programs, including healthcare subsidies, nutritional assistance, and family support, aim to enhance population health through expanded access to medical care and reduced financial barriers. However, randomized evaluations such as the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, which expanded Medicaid eligibility via lottery in 2008, revealed no statistically significant improvements in objective physical health outcomes, including blood pressure, cholesterol, or self-reported health measures beyond initial mental health gains, over the first two years of coverage.[182] [183] Later analyses of the same cohort confirmed null effects on mortality and most cardiovascular risk factors, though some subgroups showed modest reductions in systolic blood pressure.[184] [185] Descriptive studies of broader social assistance often associate receipt with adverse self-rated health and higher healthcare costs, potentially due to selection into programs among those with preexisting conditions or behavioral factors.[186] [187] In education, children from families dependent on social services exhibit persistently lower academic achievement and attainment compared to peers from non-recipient households, with longitudinal data indicating that greater exposure to welfare correlates with reduced high school completion and college enrollment rates.[188] [189] Children involved in child welfare systems, including foster care placements prompted by family instability or neglect often linked to economic dependency, demonstrate worse outcomes across metrics such as exam scores, attendance, and exclusion rates, even after controlling for baseline socioeconomic status.[190] [191] Higher welfare benefit levels have been causally tied to diminished long-term educational attainment among poor children, as generous guarantees reduce parental incentives for skill-building investments and exacerbate family disruptions that impair cognitive development.[192] Regarding family stability, empirical analyses consistently find that welfare participation lowers the likelihood of marriage formation and increases nonmarital fertility, with hazard models estimating a 33% reduction in transition rates to marriage among recipients.[193] [194] These effects stem from benefit structures that penalize two-parent households through reduced eligibility or cliffs, effectively subsidizing single parenthood; for instance, programs like TANF and related aids provide higher effective support to unmarried mothers, contributing to elevated divorce risks and lower marital stability over time.[195] [196] Reforms introducing work requirements, such as the 1996 U.S. welfare changes, modestly boosted marriage rates among long-term single recipients by 10-20% in demonstration projects, underscoring how dependency-oriented designs undermine family formation.[197] Resulting family fragmentation, in turn, causally predicts poorer child socioemotional and economic outcomes, independent of income levels.[198]Long-Term Fiscal and Economic Consequences