Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

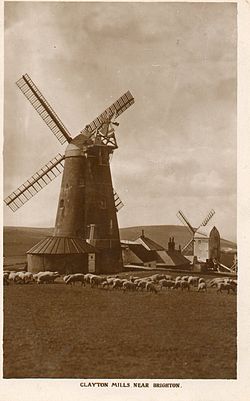

Tower mill

View on Wikipedia

A tower mill is a type of vertical windmill consisting of a brick or stone tower, on which sits a wooden 'cap' or roof, which can rotate to bring the sails into the wind.[1][2][3][4][5]

This rotating cap on a firm masonry base gave tower mills great advantages over earlier post mills, as they could stand much higher, bear larger sails, and thus afford greater reach into the wind. Windmills in general had been known to civilization for centuries, but the tower mill represented an improvement on traditional western-style windmills. The tower mill was an important source of power for Europe for nearly 600 years from 1300 to 1900, contributing to 25 percent of the industrial power of all wind machines before the advent of the steam engine and coal power.[6]

It represented a modification or a demonstration of improving and adapting technology that had been known by humans for ages. Although these types of mills were effective, some argue that, owing to their complexity, they would have initially been built mainly by the most wealthy individuals.[7]

History

[edit]The tower mill originated in written history in the late 13th century in Western Europe; the earliest record of its existence is from 1295, from Stephen de Pencastor of Dover, but the earliest illustrations date from 1390.[8] Other early examples come from Yorkshire and Buckinghamshire.[9] Other sources pin its earliest inception back in 1180 in the form of an illustration on a Norman deed, showing this new western-style windmill.[10] The Netherlands has six mills recorded before the year 1407. One of the earliest tower mills in Britain was Chesterton Windmill, Warwickshire, which has a hollowed conical base with arches. The large part of its development continued through the Late Middle Ages. Towards the end of the 15th century, tower mills began appearing across Europe in greater numbers.

The origins of the tower mill can be found in a growing economy of Europe, which needed a more reliable and efficient form of power, especially one that could be used away from a river bank. Post mills dominated the scene in Europe until the 19th century when tower mills began to replace them in such places as Billingford Mill in Norfolk, Upper Hellesdon Mill in Norwich, and Stretham Mill in Cambridgeshire.[11]

The tower mill also was seen as a cultural object, being painted and designed with aesthetic appeal in mind. Styles of the mills reflected on local tradition and weather conditions, for example mills built on the western coast of Britain were mainly built of stone to withstand the stronger winds, and those built in the east were mainly of brick.[12]

In England around 12 eight-sailers, more than 50 six- and 50 five-sailers were built in the late 18th century and 19th century, half of them in Lincolnshire. Of the eight sailed mills only Pocklington's Mill in Heckington survived in fully functional state. A few of the other ones exist as four-sailed mills (Old Buckenham), as residences (Diss Button's Mill), as ruins (Leach's Windmill, Wisbech), or have been dismantled (Holbeach Mill; Skirbeck Mill, Boston). In Lincolnshire some of the six-sailed (Sibsey Trader Mill, Waltham Windmill) and five-sailed (Dobson's Mill in Burgh le Marsh, Maud Foster Windmill in Boston, Hoyle's Mill in Alford) slender (mostly tarred) tower mills with their white onion-shaped cap and a huge fantail are still there and working today. Other former five- and six-sailed Lincolnshire and Yorkshire tower mills now without sails and partly without cap are LeTall's Mill in Lincoln, Holgate Windmill in Holgate, York (currently being restored), Black, Cliff, or Whiting's Mill (a seven-storeyed chalk mill) in Hessle and (with originally six sails) Barton-upon-Humber Tower mill, Brunswick Mill in Long Sutton, Lincolnshire, Metheringham Windmill, Penny Hill Windmill in Holbeach, Wragby Mill (built by E. Ingledew in 1831, millwright of Heckington Mill in 1830), and Wellingore Tower Mill. Another fine six-sailer can be found in Derbyshire – England's only sandstone towered windmill at Heage of 1791.

Design

[edit]

The advantage of the tower mill over the earlier post mill is that it is not necessary to turn the whole mill ("body", "buck") with all its machinery into the wind; this allows more space for the machinery as well as for storage. However, select tower mills found around Holland were constructed on a wooden frame so as to rotate the entire foundation of the mill along with the cap. These towers were often constructed out of wood rather than masonry as well.[13][14] A movable head which could pivot to react to the changing wind patterns was the most important aspect of the tower mill. This ability gave the advantage of a larger and more stable frame that could deal with harsh weather. Also, only moving a cap was much easier than moving an entire structure.

In the earliest tower mills the cap was turned into the wind with a long tail-pole which stretched down to the ground at the back of the mill. Later an endless chain was used which drove the cap through gearing. In 1745 an English engineer, Edmund Lee, invented the windmill fantail – a little windmill mounted at right angles to the sails, at the rear of the mill, and which turned the cap automatically to bring it into the wind.[15]

Like other windmills tower mills have normally four blades. To increase windmill efficiency millwrights experimented with different methods:

- automated patent-sails instead of cloth spread type sails didn't need the sail cross to be stopped to spread or remove the cloth sails because they altered the surface from inside the mill by means of a controlling gear.

- more than four blades to increase the sail surface.

Therefore, engineer John Smeaton invented the cast-iron Lincolnshire cross to make sail-crosses with five, six, and even eight blades possible. The cross was named after Lincolnshire where it was most widely used.

There are several components to the tower mill as it was in the 19th century in Europe in its most developed stage, some elements such as the gallery are not present in all tower mills:[16]

- Stock – the arm that protrudes from the top of windmill holding the frame of the sail in place, this is the main support of the sail and is usually made of wood.

- Sail – the turning frame that catches the wind, attached and held by the stock. The traditional style found on most tower mills is a four-sail frame, however in the Mediterranean model there is usually an eight-sail frame. An example of this in St. Mary's Mill on the Isle of Sicilly constructed in 1820.

- Windshaft – A particularly important part of the sail frame, the windshaft is the cylindrical piece that translates the movement of the sail into the machinery within the windmill.

- Cap – The top of the tower that holds the sail and stock, this piece is able to rotate on top of the tower.

- Tower – Supports the cap, the main structure of the tower mill.

- Floor – Base level of the tower inside, usually where grain or other products are stored.

- Gallery – Deck surrounding the floor outside the tower to provide access around the tower mill if it is raised, not present in all tower mills. The gallery allowed access to the sails for making repairs because they could not be easily reached from the ground in larger mills.[17]

- Frame – Sail design that forms the outline of the sail, usually a meshed wood design that then is covered in cloth. The Mediterranean design is different in that there are several sails on the sail-frame and each supports a draped cloth and there is no wooden frame behind it.

- Fantail – Orientation device that is attached to the cap, allowing it to rotate to keep the sails in the direction of the wind.

- Hemlath – Thick wooden sailbar on the side of the frame that keeps the narrower sailbars inside the sail.

- Sailbar – Elongated piece of wood that forms a sail.

- Sail cloth – Cloth attached to a sail that collects wind energy; a large sail cloth is used for weak winds and a small sail cloth for strong winds.

Application

[edit]

The tower mill was more powerful than the water mill, able to generate roughly 14.7 to 22.1 kilowatt (20 to 30 horsepower).[18] There were many uses that the tower mill had aside from grinding corn. It is sometimes said that tower mills fuelled a society that was steadily growing in its need for power by providing a service to other industries as well:[19]

- The production of pepper and other spices

- Lumber companies used them for powering sawmills

- Paper companies used to change wood pulp into paper

Other sources argue against this claiming there is no real evidence, specifically, of tower mills doing these things.[3]

Interesting facts

[edit]

The world's tallest tower mills can be found in Schiedam, Netherlands. Dutch: De Noord, meaning 'the North', is a corn mill dating to 1803 that is 33.3 metres (109 ft) to the cap. In 2006 an imitation, De Nolet (named after the local Nolet distilling family who owns the mill), was built as a generator mill producing electricity that is 42.5 metres (139 ft) to the cap.

England's tallest tower mill is the nine-storeyed Moulton Windmill in Moulton, Lincolnshire, with a cap height of 30 metres (98 ft). Since 2005 the mill has a new white rotatable cap with windshaft and fantail in place. The stage was erected during 2008 and new sails were fitted on 21 November 2011 to complete the restoration of the mill.[21] Larger mills have been lost, such as the Great Yarmouth Southtown mill that was 37 metres (120 ft) to the top of the lantern that functioned as a lighthouse,[22] and Bixley tower mill that was 42 metres (137 ft) to the cap top,[23] both in Norfolk.

In the Netherlands windmills named tower mills (torenmolens) have a compact, cylindrical or only slightly conical tower. In the southern Netherlands four mills of that type (Dutch definition) survive, the oldest one dating from before 1441. The cap of three of those mills is turned by a luffing gear built in the cap. Older types of tower mill with a fixed cap were found in castles, fortresses or inside city walls from the 14th century, and are still be found around the Mediterranean Sea. They were built with the sails facing the prevailing wind direction.

Tower mills were very expensive to build, with cost estimates suggesting almost twice that of post mills; this is in part why they were not very prevalent until centuries after their invention. Sometimes these mills were even built on the sides of castles and towers in fortified towns to make them resistant to attacks. Some tower mills were still in operation well into the 20th century in southern parts of the United Kingdom.[24]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Righter, Wind energy in America: A History, (1996) 14

- ^ A short history of technology: from the earliest times to A.D. 1900 (1993), 255

- ^ a b Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia (2005), 520

- ^ Watts, Water and wind power (2000), 125

- ^ Ball, Natural sources of power (1908), 243

- ^ Righter, Wind energy in America: A History, (1996) 15

- ^ Langdon, Mills in the medieval economy: England, 1300–1540 (2004), 115

- ^ Hills, Power from wind: a history of windmill technology, (1996) 51–60

- ^ Langdon, Mills in the medieval economy: England, 1300–1540 (2004), 114

- ^ A short history of technology: from the earliest times to A.D. 1900 (1993), 254

- ^ Hills, Power from wind: a history of windmill technology, (1996), 65

- ^ Hills, Power from wind: a history of windmill technology, (1996), 63

- ^ Journal of the Franklin Institute, Volume 187 (1919), 177

- ^ Miller in Eighteenth Century Virginia (1958), 7

- ^ Cipolla Before the industrial revolution: European society and economy, 1000–1700 (1994), 144

- ^ http://visual.merriam-webster.com/energy/wind-energy/windmill/tower-mill.php visited 23 November 2009

- ^ Ball, Natural sources of power (1908), 248

- ^ Cipolla, Before the industrial revolution: European society and economy, 1000–1700 (1994), 144

- ^ Wind energy in America: A History (1996), 15

- ^ Spiteri, Stephen C. (May 2008). "Maltese 'siege' batteries of the blockade 1798-1800" (PDF). Arx - Online Journal of Military Architecture and Fortification (6): 30–31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Lincolnshire mill gets new sails". BBC News. 22 November 2011 – via BBC.

- ^ "Norfolk Mills - Gt Yarmouth Southtown High Mill tower windmill". www.norfolkmills.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Norfolk Mills - Bixley towermill". www.norfolkmills.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Wind, water, work: ancient and medieval milling technology (2006), 122

References

[edit]- Lucas, Adam . Wind, water, work: ancient and medieval milling technology. (BRILL, 2006)

- Righter, Robert W. Wind energy in America: A History. (University of Oklahoma Press, 1996)

- Hills, Richard Leslie. Power from wind: a history of windmill technology. (Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- Langdon, John. Mills in the medieval economy: England, 1300–1540. (Oxford University Press, 2004)

- Thomas Kingston Derry and Trevor Illtyd William. A short history of technology: from the earliest times to A.D. 1900. (Courier Dover Publications, 1993)

- Thomas F. Glick, Steven John Livesey, and Faith Wallis. Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia: Volume 11 of Routledge encyclopedias of the Middle Ages. (Routledge, 2005)

- Harvard University. Journal of the Franklin Institute, Volume 187. (Pergamon Press, 1919)

- Watts, Martin. Water and wind power. (Osprey Publishing, 2000)

- Ball, Robert Steele. Natural sources of power. (D. Van Nostrand company, 1908)

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Miller in Eighteenth Century Virginia. (Colonial Williamsburg, 1958)

- Cipolla, Carlo M. Before the industrial revolution: European society and economy, 1000–1700. (W. W. Norton & Company, 1994)

External links

[edit]- Chesterton Windmill

- Interesting smaller site about Tower Mills

- Shows components of the Tower Mill

- Several interesting images of Tower Mills

- Dutch website presenting the "Lana Mariana" windmill at Ede with a built-in restaurant

- Morgan Lewis Windmill, Barbados. A good example of a tower mill with tail tree

- Dutch tower mill Noletmolen traditional style mill built in 2005 to generate electricicty – Dutch text.

- Fédération Des Moulins de France