Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Traditionalist Communion

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (December 2016) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

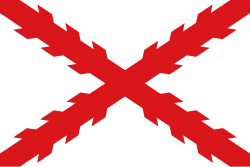

The Traditionalist Communion (Spanish: Comunión Tradicionalista, CT; Basque: Elkarte Tradizionalista, Catalan: Comunió Tradicionalista) was one of the names adopted by the Carlist movement as a political force since 1869.[1]

Key Information

History

[edit]In October 1931, Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne Duke Jaime died. He was succeeded by the 82-year-old claimant Alfonso Carlos de Borbón, reuniting under him the integrists led by Olazábal and the "Mellists". They represented a region-based Spanish nationalism with an entrenched identification of Spain and Catholicism. The ensuing radicalized Carlist scene overshadowed the "Jaimists" with a Basque inclination. The Basque(-Navarrese) Statute failed to take off over disagreements on the centrality of Catholicism in 1932, with the new Carlist party Comunión Tradicionalista opting for an open confrontation with the Republic. The Republic established a secular approach of the regime, a division of Church and state, as well as freedom of religion, as France did in 1905, an approach traditionalists could not stand.

The Comunión Tradicionalista (1932) showed an ultra-Catholic, anti-secular position, and plotted for a military takeover, while adopting far-right apocalyptic views and talking of a final clash with an alliance of alleged anti-Christian forces.[2]

The October 1934 Revolution cost the life of the Carlist deputy Marcelino Oreja Elósegui, with Manuel Fal Condé taking over from young Carlists clustering around the AET (Jaime del Burgo and Mario Ozcoidi) in their pursuit to overthrow the Republic. The Carlists started to prepare for an armed definite clash with the Republic and its different leftist groups. From the initial defensive Decurias of Navarre (deployed in party seats and churches), the Requeté grew into a well-trained and strongest offensive paramilitary group in Spain when Manuel Fal Condé took the reins. It numbered 30,000 red berets (8,000 in Navarre and 22,000 in Andalusia).[2]

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936 following the election of a coalition of socialist, communist, and anarchist parties, the Traditionalist Communion sided with the Spanish Nationalists, despite ideological differences with the Falangists, out of shared Catholicism and repression under the Republic. Seeking to unify all Nationalist Forces, the General Francisco Franco announced that all political parties, other than FET y de las JONS, were dissolved, and the Traditionalist Communion ceased to exist.[3]

Ideology

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Spain |

|---|

|

Carlism is a reactionary, monarchist, and extremely Catholic ideology. It developed after the King Ferdinand VII changed the succession laws by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830, meaning Don Carlos would no longer become the next king. Its main tenets are "God, Country, and King", and it spawned many other political parties, the most notable of which was the Carlist Party of Euskal Herria, which was formed as an underground party during the fascist government and went on to run in the elections following the democratization of Spain.

Legacy

[edit]Carlism remained a scattered movement until the end of the dictatorship. While a fraction of the movement actively supported the Francoist regime, most of Carlists were forced to go underground.

The Traditionalist Communion was reorganised during the 1950s and 1960s in a situation of illegality and prohibition imposed in Francoist Spain to university and workers' organisations of non-integrated Carlism (Group of Traditionalist Students, AET at the university; Traditionalist Worker’s Movement, MOT) into the Francoist only official party, with the support of prince Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma.

In 1970, the Carlist Party was officially established by a Congress of the Carlist People in Arbonne, in which it adopted a program for the ideological change of Carlism towards self-management socialism and the conversion of the Carlist movement into a federal and democratic party of the masses on a class basis which aspired a pact between the dynasty and the people to a socialist monarchy.

The socialistic turn of both Duke Carlos Hugo and his son Prince Carlos, Duke of Parma was rejected by the more right-wing factions of Carlism, under the leadership of Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma, who re-established the Traditionalist Communion in 1975. In 1986, the Communion, alongside two other right-wing Carlist Party, established the Traditionalist Carlist Communion, a political party which promotes the traditional version of Carlism, based upon integrism, foralism and reactionism.

References

[edit]- ^ "Carlistas y Tradicionalistas (1868–1931)". historiaelectoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ a b Preston, Paul (2013). The Spanish holocaust : inquisition and extermination in twentieth-century Spain. London: HarperPress. ISBN 978-0-00-638695-7. OCLC 810945953.

- ^ Carlism in the Spanish Rising of 1936.

.svg/250px-Coat_of_Arms_used_by_the_supporters_of_the_Carlist_Claimants_to_the_Spanish_Throne_(adopted_c.1890).svg.png)

.svg/1319px-Coat_of_Arms_used_by_the_supporters_of_the_Carlist_Claimants_to_the_Spanish_Throne_(adopted_c.1890).svg.png)