Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

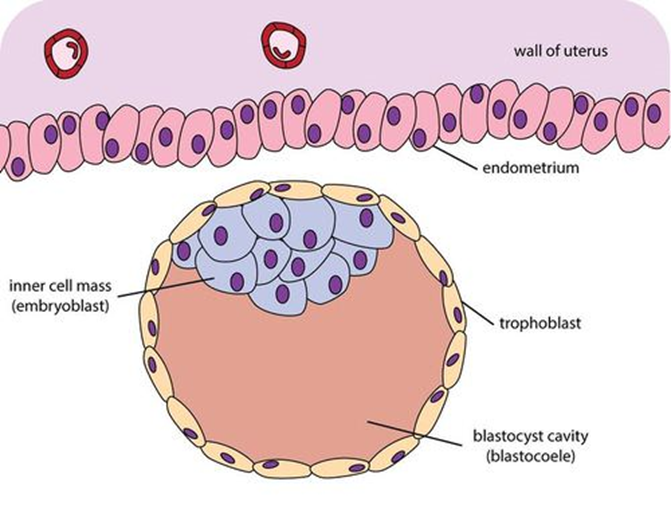

Trophoblast

View on Wikipedia| Trophoblast | |

|---|---|

Blastocyst with an inner cell mass and trophoblast. | |

| Details | |

| Days | 6 |

| Gives rise to | Caul |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | trophoblastus; massa cellularis externa |

| MeSH | D014327 |

| TE | E6.0.1.1.2.0.2 |

| FMA | 83029 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The trophoblast (from Greek trephein: to feed; and blastos: germinator) is the outer layer of cells of the blastocyst. Trophoblasts are present four days after fertilization in humans.[1] They provide nutrients to the embryo and develop into a large part of the placenta.[2][3] They form during the first stage of pregnancy and are the first cells to differentiate from the fertilized egg to become extraembryonic structures that do not directly contribute to the embryo. After blastulation, the trophoblast is contiguous with the ectoderm of the embryo and is referred to as the trophectoderm. [4] After the first differentiation, the cells in the human embryo lose their totipotency because they can no longer form a trophoblast. They become pluripotent stem cells.

Structure

[edit]

The trophoblast proliferates and differentiates into two cell layers at approximately six days after fertilization for humans.

| Layer | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotrophoblast | The inner layer | A single-celled inner layer of the trophoblast. |

| Syncytiotrophoblast | The outer layer | A thick layer that lacks cell boundaries and grows into the endometrial stroma. It secretes hCG in order to maintain progesterone secretion and sustain a pregnancy. |

| Intermediate trophoblast (IT) | The implantation site, chorion, villi (dependent on subtype) | An anchor placenta (implantation site IT). |

Function

[edit]Trophoblasts are specialized cells of the placenta that play an important role in embryo implantation and interaction with the decidualized maternal uterus.[5] The core of placental villi contain mesenchymal cells and placental blood vessels that are directly connected to the fetus’ circulation via the umbilical cord. This core is surrounded by two layers of trophoblasts, the cytotrophoblast and the syncytiotrophoblast. The cytotrophoblast is a layer of mono-nucleated cells that resides underneath the syncytiotrophoblast.[6] The syncytiotrophoblast is composed of fused cytotrophoblasts which then form a layer that covers the placental surface.[6] The syncytiotrophoblast is in direct contact with the maternal blood that reaches the placental surface. It then facilitates the exchange of nutrients, wastes and gases between the maternal and fetal systems.

In addition, cytotrophoblasts in the tips of villi can differentiate into another type of trophoblast called the extravillous trophoblast. Extravillous trophoblasts grow out from the placenta and penetrate into the decidualized uterus. This process is essential not only for physically attaching the placenta to the mother, but also for altering the vasculature in the uterus. This alteration allows an adequate blood supply to the growing fetus as pregnancy progresses. Some of these trophoblasts even replace the endothelial cells in the uterine spiral arteries as they remodel these vessels into wide bore conduits that are independent of maternal vasoconstriction. This ensures that the fetus receives a steady supply of blood, and the placenta is not subjected to fluctuations in oxygen that could cause it damage.[7]

Clinical significance

[edit]The invasion of a specific type of trophoblast (extravillous trophoblast) into the maternal uterus is a vital stage in the establishment of pregnancy. Failure of the trophoblast to invade sufficiently is important in the development of some cases of pre-eclampsia. Invasion of the trophoblast too deeply may cause conditions such as placenta accreta, placenta increta, or placenta percreta.

Gestational trophoblastic disease is a pregnancy-associated concept, forming from the villous and extravillous trophoblast cells in the placenta.[8]

Choriocarcinoma are trophoblastic tumors that form in the uterus from villous cells.[8]

Trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) are cells that can regenerate and they are similar to embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in the fact that they come from early on in the trophoblast lifetime.[9] In the placenta, these stem cells are able to differentiate into any trophoblast cell because they are pluripotent.[9]

Additional images

[edit]-

Blastodermic vesicle of Vespertilio murinus.

-

Section through embryonic disk of Vespertilio murinus.

-

Transverse section of a chorionic villus.

-

Scheme of placental circulation.

-

The initial stages of human embryogenesis

-

Histopathology of a chorionic villus, in a tubal pregnancy, with labeled cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tang, Jiaqi; Liu, Bailin; Li, Na; Zhang, Mengshu; Li, Xiang; Gao, Qinqin; Zhou, Xiuwen; Sun, Miao; Xu, Zhice; Lu, Xiyuan (2020). "Development of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone and Nitric Oxide System in the Fetus and Neonate". Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Endocrinology. pp. 643–662. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814823-5.00038-6. ISBN 978-0-12-814823-5. S2CID 208378249.

- ^ Soares, Michael J.; Varberg, Kaela M. (2018). "Trophoblast". Encyclopedia of Reproduction. pp. 417–423. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.64664-0. ISBN 978-0-12-815145-7.

- ^ Baines, K.J.; Renaud, S.J. (2017). "Transcription Factors That Regulate Trophoblast Development and Function". Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 145: 39–88. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.12.003. ISBN 978-0-12-809327-6. PMID 28110754.

- ^ Douglas, Gordon C.; VandeVoort, Catherine A.; Kumar, Priyadarsini; Chang, Tien-Cheng; Golos, Thaddeus G. (2009-03-18). "Trophoblast Stem Cells: Models for Investigating Trophectoderm Differentiation and Placental Development". Endocrine Reviews. 30 (3). The Endocrine Society: 228–240. doi:10.1210/er.2009-0001. ISSN 0163-769X. PMC 2726840. PMID 19299251.

- ^ Imakawa, K.; Nakagawa, S. (2017). "The Phylogeny of Placental Evolution Through Dynamic Integrations of Retrotransposons". Molecular Biology of Placental Development and Disease. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol. 145. pp. 89–109. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.12.004. ISBN 978-0-12-809327-6. PMID 28110755.

- ^ a b "The trophoblast". Archived from the original on 15 December 2007.

- ^ Lunghi, Laura; Ferretti, Maria E; Medici, Silvia; Biondi, Carla; Vesce, Fortunato (December 2007). "Control of human trophoblast function". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 5 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-5-6. PMC 1800852. PMID 17288592.

- ^ a b Ning, Fen; Hou, Houmei; Morse, Abraham N.; Lash, Gendie E. (10 April 2019). "Understanding and management of gestational trophoblastic disease". F1000Research. 8: 428. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14953.1. PMC 6464061. PMID 31001418.

- ^ a b Latos, P.A.; Hemberger, M. (February 2014). "Review: The transcriptional and signalling networks of mouse trophoblast stem cells". Placenta. 35: S81 – S85. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.10.013. PMID 24220516.

External links

[edit]- Swiss embryology (from UL, UB, and UF) iperiodembry/carnegie02