Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scapula

View on Wikipedia| Scapula | |

|---|---|

| |

The upper picture is an anterior (from the front) view of the thorax and shoulder girdle. The lower picture is a posterior (from the rear) view of the thorax (scapula shown in red). | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | scapula (omo) |

| MeSH | D012540 |

| TA98 | A02.4.01.001 |

| TA2 | 1143 |

| FMA | 13394 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The scapula (pl.: scapulae or scapulas[1]), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side of the body being roughly a mirror image of the other. The name derives from the Classical Latin word for trowel or small shovel, which it was thought to resemble.

In compound terms, the prefix omo- is used for the shoulder blade in medical terminology. This prefix is derived from ὦμος (ōmos), the Ancient Greek word for shoulder, and is cognate with the Latin (h)umerus, which in Latin signifies either the shoulder or the upper arm bone.

The scapula forms the back of the shoulder girdle. In humans, it is a flat bone, roughly triangular in shape, placed on a posterolateral aspect of the thoracic cage.[2]

Structure

[edit]The scapula is a thick, flat bone lying on the thoracic wall that provides an attachment for three groups of muscles: intrinsic, extrinsic, and stabilizing and rotating muscles.

The intrinsic muscles of the scapula include the muscles of the rotator cuff (SITS muscle)—the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor.[3] These muscles attach to the surface of the scapula and are responsible for the internal and external rotation of the shoulder joint, along with humeral abduction.

The extrinsic muscles include the biceps, triceps, and deltoid muscles and attach to the coracoid process and supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, and spine of the scapula. These muscles are responsible for several actions of the glenohumeral joint.

The third group, which is mainly responsible for stabilization and rotation of the scapula, consists of the trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rhomboid muscles. These attach to the medial, superior, and inferior borders of the scapula.

The head, processes, and the thickened parts of the bone contain cancellous tissue; the rest consists of a thin layer of compact tissue.

The central part of the supraspinatus fossa and the upper part of the infraspinatous fossa, but especially the former, are usually so thin in humans as to be semitransparent; occasionally the bone is found wanting in this situation, and the adjacent muscles are separated only by fibrous tissue. The scapula has two surfaces, three borders, three angles, and three processes.

Surfaces

[edit]

Front or subscapular fossa

[edit]The front of the scapula (also known as the costal or ventral surface) has a broad concavity called the subscapular fossa, to which the subscapularis muscle attaches. The medial two-thirds of the fossa have 3 longitudinal oblique ridges, and another thick ridge adjoins the lateral border; they run outward and upward. The ridges give attachment to the tendinous insertions, and the surfaces between them to the fleshy fibers, of the subscapularis muscle. The lateral third of the fossa is smooth and covered by the fibers of this muscle.

At the upper part of the fossa is a transverse depression, where the bone appears to be bent on itself along a line at right angles to and passing through the center of the glenoid cavity, forming a considerable angle, called the subscapular angle; this gives greater strength to the body of the bone by its arched form, while the summit of the arch serves to support the spine and acromion.

The costal surface superior of the scapula is the origin of 1st digitation for the serratus anterior origin.

|

|

|

Back

[edit]The back of the scapula (also called the dorsal or posterior surface) is arched from above downward, and is subdivided into two unequal parts by the spine of the scapula. The portion above the spine is called the supraspinous fossa, and that below it the infraspinous fossa. The two fossae are connected by the spinoglenoid notch, situated lateral to the root of the spine.

- The supraspinous fossa, above the spine of scapula, is concave, smooth, and broader at its vertebral than at its humeral end; its medial two-thirds give origin to the Supraspinatus. At its lateral surface resides the spinoglenoid fossa which is situated by the medial margin of the glenoid. The spinoglenoid fossa houses the suprascapular canal which forms a connecting passage between the suprascapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch conveying the suprascapular nerve and vessels.[4]

- The infraspinous fossa is much larger than the preceding; toward its vertebral margin a shallow concavity is seen at its upper part; its center presents a prominent convexity, while near the axillary border is a deep groove which runs from the upper toward the lower part. The medial two-thirds of the fossa give origin to the Infraspinatus; the lateral third is covered by this muscle.

There is a ridge on the outer part of the back of the scapula. This runs from the lower part of the glenoid cavity, downward and backward to the vertebral border, about 2.5 cm above the inferior angle. Attached to the ridge is a fibrous septum, which separates the infraspinatus muscle from the Teres major and Teres minor muscles. The upper two-thirds of the surface between the ridge and the axillary border is narrow, and is crossed near its center by a groove for the scapular circumflex vessels; the Teres minor attaches here.

The broad and narrow portions above alluded to are separated by an oblique line, which runs from the axillary border, downward and backward, to meet the elevated ridge: to it is attached a fibrous septum which separates the Teres muscles from each other.

Its lower third presents a broader, somewhat triangular surface, the inferior angle of the scapula, which gives origin to the Teres major, and over which the Latissimus dorsi glides; frequently the latter muscle takes origin by a few fibers from this part.

|

|

|

Side

[edit]The acromion forms the summit of the shoulder, and is a large, somewhat triangular or oblong process, flattened from behind forward, projecting at first laterally, and then curving forward and upward, so as to overhang the glenoid cavity.

|

|

|

Angles

[edit]There are 3 angles:

The superior angle of the scapula or medial angle, is covered by the trapezius muscle. This angle is formed by the junction of the superior and medial borders of the scapula. The superior angle is located at the approximate level of the second thoracic vertebra. The superior angle of the scapula is thin, smooth, rounded, and inclined somewhat lateralward, and gives attachment to a few fibers of the levator scapulae muscle.[5]

The inferior angle of the scapula is the lowest part of the scapula and is covered by the latissimus dorsi muscle. It moves forwards round the chest when the arm is abducted. The inferior angle is formed by the union of the medial and lateral borders of the scapula. It is thick and rough and its posterior or back surface affords attachment to the teres major and often to a few fibers of the latissimus dorsi. The anatomical plane that passes vertically through the inferior angle is named the scapular line.

The lateral angle of the scapula or glenoid angle, also known as the head of the scapula, is the thickest part of the scapula. It is broad and bears the glenoid fossa on its articular surface which is directed forward, laterally and slightly upwards, and articulates with the head of the humerus. The inferior angle is broader below than above and its vertical diameter is the longest. The surface is covered with cartilage in the fresh state; and its margins, slightly raised, give attachment to a fibrocartilaginous structure, the glenoidal labrum, which deepens the cavity. At its apex is a slight elevation, the supraglenoid tuberosity, to which the long head of the biceps brachii is attached.[6]

The anatomic neck of the scapula is the slightly constricted portion which surrounds the head and is more distinct below and behind than above and in front. The surgical neck of the scapula passes directly medial to the base of the coracoid process.[7]

-

Superior angle shown in red

-

Lateral angle shown in red

-

Anatomic neck: red, Surgical neck: purple

-

Inferior angle shown in red

Borders

[edit]

There are three borders of the scapula:

- The superior border is the shortest and thinnest; it is concave, and extends from the superior angle to the base of the coracoid process. It is referred to as the cranial border in animals.

- At its lateral part is a deep, semicircular notch, the scapular notch, formed partly by the base of the coracoid process. This notch is converted into a foramen by the superior transverse scapular ligament, and serves for the passage of the suprascapular nerve; sometimes the ligament is ossified.

- The adjacent part of the superior border affords attachment to the omohyoideus.

-

Costal surface of left scapula. Superior border shown in red.

-

Left scapula. Superior border shown in red.

-

Animation. Superior border shown in red.

- The axillary border (or "lateral border") is the thickest of the three. It begins above at the lower margin of the glenoid cavity, and inclines obliquely downward and backward to the inferior angle. It is referred to as the caudal border in animals.

- It begins above at the lower margin of the glenoid cavity, and inclines obliquely downward and backward to the inferior angle.

- Immediately below the glenoid cavity is a rough impression, the infraglenoid tuberosity, about 2.5 cm (1 in). in length, which gives origin to the long head of the triceps brachii; in front of this is a longitudinal groove, which extends as far as the lower third of this border, and affords origin to part of the subscapularis.

- The inferior third is thin and sharp, and serves for the attachment of a few fibers of the teres major behind, and of the subscapularis in front.

-

Dorsal surface of left scapula. Lateral border shown in red.

-

Left scapula. Lateral border shown in red.

-

Animation. Lateral border shown in red.

- The medial border (also called the vertebral border or medial margin) is the longest of the three borders, and extends from the superior angle to the inferior angle.[8] In animals it is referred to as the dorsal border.

- Four muscles attach to the medial border. Serratus anterior has a long attachment on the anterior lip. Three muscles insert along the posterior lip, the levator scapulae (uppermost), rhomboid minor (middle), and to the rhomboid major (lower middle).[8]

-

Left scapula. Medial border shown in red.

-

Animation. Medial border shown in red.

-

Still image. Medial border shown in red.

-

Levator scapulae muscle (red)

-

Rhomboid minor muscle (red)

-

Rhomboid major muscle (red)

Development

[edit]

The scapula is ossified from 7 or more centers: one for the body, two for the coracoid process, two for the acromion, one for the vertebral border, and one for the inferior angle. Ossification of the body begins about the second month of fetal life, by an irregular quadrilateral plate of bone forming, immediately behind the glenoid cavity. This plate extends to form the chief part of the bone, the scapular spine growing up from its dorsal surface about the third month. Ossification starts as membranous ossification before birth.[9][10] After birth, the cartilaginous components would undergo endochondral ossification. The larger part of the scapula undergoes membranous ossification.[11] Some of the outer parts of the scapula are cartilaginous at birth, and would therefore undergo endochondral ossification.[12]

At birth, a large part of the scapula is osseous, but the glenoid cavity, the coracoid process, the acromion, the vertebral border and the inferior angle are cartilaginous. From the 15th to the 18th month after birth, ossification takes place in the middle of the coracoid process, which as a rule becomes joined with the rest of the bone about the 15th year.

Between the 14th and 20th years, the remaining parts ossify in quick succession, and usually in the following order: first, in the root of the coracoid process, in the form of a broad scale; secondly, near the base of the acromion; thirdly, in the inferior angle and contiguous part of the vertebral border; fourthly, near the outer end of the acromion; fifthly, in the vertebral border. The base of the acromion is formed by an extension from the spine; the two nuclei of the acromion unite, and then join with the extension from the spine. The upper third of the glenoid cavity is ossified from a separate center (sub coracoid), which appears between the 10th and 11th years and joins between the 16th and the 18th years. Further, an epiphysial plate appears for the lower part of the glenoid cavity, and the tip of the coracoid process frequently has a separate nucleus. These various epiphyses are joined to the bone by the 25th year.

Failure of bony union between the acromion and spine sometimes occurs (see os acromiale), the junction being effected by fibrous tissue, or by an imperfect articulation; in some cases of supposed fracture of the acromion with ligamentous union, it is probable that the detached segment was never united to the rest of the bone.

"In terms of comparative anatomy the human scapula represents two bones that have become fused together; the (dorsal) scapula proper and the (ventral) coracoid. The epiphyseal line across the glenoid cavity is the line of fusion. They are the counterparts of the ilium and ischium of the pelvic girdle."

— R. J. Last – Last's Anatomy

Function

[edit]The following muscles attach to the scapula:

| Muscle | Direction | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Pectoralis minor | Insertion | Coracoid process |

| Coracobrachialis | Origin | Coracoid process |

| Serratus anterior | Insertion | Medial border |

| Triceps brachii (long head) | Origin | Infraglenoid tubercle |

| Biceps brachii (short head) | Origin | Coracoid process |

| Biceps brachii (long head) | Origin | Supraglenoid tubercle |

| Subscapularis | Origin | Subscapular fossa |

| Rhomboid major | Insertion | Medial border |

| Rhomboid minor | Insertion | Medial border |

| Levator scapulae | Insertion | Medial border |

| Trapezius | Insertion | Spine of scapula |

| Deltoid | Origin | Spine of scapula |

| Supraspinatus | Origin | Supraspinous fossa |

| Infraspinatus | Origin | Infraspinous fossa |

| Teres minor | Origin | Lateral border |

| Teres major | Origin | Lateral border |

| Latissimus dorsi (a few fibers; attachment may be absent) | Origin | Inferior angle |

| Omohyoid | Origin | Superior border |

Movements

[edit]Movements of the scapula are brought about by the scapular muscles. The scapula can perform six actions:

- Elevation: upper trapezius and levator scapulae

- Depression: lower trapezius

- Retraction (adduction): rhomboids and middle trapezius

- Protraction (abduction): serratus anterior

- Upward rotation: upper and lower trapezius, serratus anterior

- Downward rotation: rhomboids,[13][14] Levator Scapulae, and Pec Minor

Clinical significance

[edit]Scapular fractures

[edit]

Because of its sturdy structure and protected location, fractures of the scapula are uncommon. When they do occur, they are an indication that severe chest trauma has occurred.[15] Scapular fractures involving the neck of the scapula have two patterns. One (rare) type of fracture is through the anatomical neck of the scapula. The other more common type of fracture is through the surgical neck of the scapula. The surgical neck exits medial to the coracoid process.[16]

An abnormally protruding inferior angle of the scapula is known as a winged scapula and can be caused by paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle. In this condition the sides of the scapula nearest the spine are positioned outward and backward. The appearance of the upper back is said to be wing-like. In addition, any condition causing weakness of the serratus anterior muscle may cause scapular "winging".

Scapular dyskenesis

[edit]The scapula plays an important role in shoulder impingement syndrome.[17]

Abnormal scapular function is called scapular dyskinesis. The scapula performs elevation of the acromion process during a throwing or serving motion, in order to avoid impingement of the rotator cuff tendons.[17] If the scapula fails to properly elevate the acromion, impingement may occur during the cocking and acceleration phase of an overhead activity. The two muscles most commonly inhibited during this first part of an overhead motion are the serratus anterior and the lower trapezius.[18] These two muscles act as a force couple within the glenohumeral joint to properly elevate the acromion process, and if a muscle imbalance exists, shoulder impingement may develop.

Other conditions associated with scapular dyskenesis include thoracic outlet syndrome and the related pectoralis minor syndrome.[19][20]

Etymology

[edit]The name scapula as synonym of shoulder blade is of Latin origin.[21] It is commonly used in medical English[21][22][23] and is part of the current official Latin nomenclature, Terminologia Anatomica.[24] Shoulder blade is the colloquial name for this bone.[citation needed]

In other animals

[edit]

In fish, the scapular blade is a structure attached to the upper surface of the articulation of the pectoral fin, and is accompanied by a similar coracoid plate on the lower surface. Although sturdy in cartilagenous fish, both plates are generally small in most other fish, and may be partially cartilagenous, or consist of multiple bony elements.[25]

In the early tetrapods, these two structures respectively became the scapula and a bone referred to as the procoracoid (commonly called simply the "coracoid", but not homologous with the mammalian structure of that name). In amphibians and reptiles (birds included), these two bones are distinct, but together form a single structure bearing many of the muscle attachments for the forelimb. In such animals, the scapula is usually a relatively simple plate, lacking the projections and spine that it possesses in mammals. However, the detailed structure of these bones varies considerably in living groups. For example, in frogs, the procoracoid bones may be braced together at the animal's underside to absorb the shock of landing, while in turtles, the combined structure forms a Y-shape in order to allow the scapula to retain a connection to the clavicle (which is part of the shell). In birds, the procoracoids help to brace the wing against the top of the sternum.[25]

In the fossil therapsids, a third bone, the true coracoid, formed just behind the procoracoid. The resulting three-boned structure is still seen in modern monotremes, but in all other living mammals, the procoracoid has disappeared, and the coracoid bone has fused with the scapula, to become the coracoid process. These changes are associated with the upright gait of mammals, compared with the more sprawling limb arrangement of reptiles and amphibians; the muscles formerly attached to the procoracoid are no longer required. The altered musculature is also responsible for the alteration in the shape of the rest of the scapula; the forward margin of the original bone became the spine and acromion, from which the main shelf of the shoulder blade arises as a new structure.[25]

In dinosaurs

[edit]In dinosaurs the main bones of the pectoral girdle were the scapula (shoulder blade) and the coracoid, both of which directly articulated with the clavicle. The clavicle was present in saurischian dinosaurs but largely absent in ornithischian dinosaurs. The place on the scapula where it articulated with the humerus (upper bone of the forelimb) is called the glenoid. The scapula serves as the attachment site for a dinosaur's back and forelimb muscles.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

3D image

-

Position of scapula (shown in red). Animation.

-

Shape of scapula (left). Animation.

-

Thorax seen from behind.

-

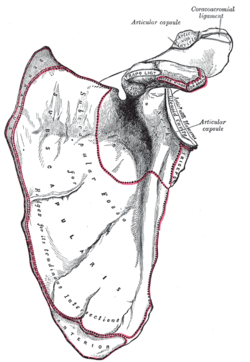

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, front view

-

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, back view

-

The scapular and circumflex arteries.

-

Left scapula. Dorsal surface. (Superior border labeled at center top.)

-

Scapula. Medial view.

-

Scapula. Anterior face.

-

Scapula. Posterior face.

-

Computer Generated turn around Image of scapula

-

Suprascapular canal path

-

Scapula Anatomy

See also

[edit]- Scapulimancy/Oracle bone the light side

References

[edit] This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 202 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 202 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ O.D.E. 2nd Ed. 2005

- ^ "Scapula (Shoulder Blade) Anatomy, Muscles, Location, Function | EHealthStar". www.ehealthstar.com. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ^ Marieb, E. (2005). Anatomy & Physiology (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings.

- ^ Al-Redouan, Azzat; Holding, Keiv; Kachlik, David (2021). ""Suprascapular canal": Anatomical and topographical description and its clinical implication in entrapment syndrome". Annals of Anatomy. 233 151593. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2020.151593. PMID 32898658.

- ^ Gray, Henry (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body, 20th ed. / thoroughly rev. and re-edited by Warren H. Lewis. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. p. 206. OL 24786057M.

- ^ Al-Redouan, Azzat; Kachlik, David (2022). "Scapula revisited: new features identified and denoted by terms using consensus method of Delphi and taxonomy panel to be implemented in radiologic and surgical practice". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 31 (2): e68-e81. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2021.07.020. PMID 34454038.

- ^ Frich, Lars Henrik; Larsen, Morten Schultz (2017). "How to deal with a glenoid fracture". EFORT Open Reviews. 2 (5): 151–157. doi:10.1302/2058-5241.2.160082. ISSN 2396-7544. PMC 5467683. PMID 28630753.

- ^ a b Shuenke, Michael (2010). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. New York: Everbest Printing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-60406-286-1.

- ^ "GE Healthcare - Home". www.gehealthcare.com.

- ^ Thaller, Seth; Scott Mcdonald, W (2004-03-23). Facial Trauma. ISBN 978-0-8247-5008-4.

- ^ "Ossification". Medcyclopaedia. GE. Archived from the original on 2011-05-26.

- ^ "II. Osteology. 6a. 2. The Scapula (Shoulder Blade). Gray, Henry. 1918. Anatomy of the Human Body".

- ^ Paine, Russ; Voight, Michael L. (2016-11-22). "The role of the scapula". International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 8 (5): 617–629. ISSN 2159-2896. PMC 3811730. PMID 24175141.

- ^ Saladin, K (2010). Anatomy & Physiology. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Livingston DH, Hauser CJ (2003). "Trauma to the chest wall and lung". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 516. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- ^ van Noort, A; van Kampen, A (Dec 2005). "Fractures of the scapula surgical neck: outcome after conservative treatment in 13 cases" (PDF). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 125 (10): 696–700. doi:10.1007/s00402-005-0044-y. PMID 16189689. S2CID 11217081. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19.

- ^ a b Kibler, BW. (1998). The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(2), 325-337.

- ^ Cools, A., Dewitte, V., Lanszweert, F., Notebaert, D., Roets, A., et al. (2007). Rehabilitation of scapular muscle balance. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(10), 1744.

- ^ Watson, L.A.; Pizzari, T.; Balster, S. (2010). "Thoracic outlet syndrome Part 2: Conservative management of thoracic outlet". Manual Therapy. 15 (4): 305–314. doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.03.002.

- ^ Ahmed, Adil S.; Graf, Alexander R.; Karzon, Anthony L.; Graulich, Bethany L.; Egger, Anthony C.; Taub, Sarah M.; Gottschalk, Michael B.; Bowers, Robert L.; Wagner, Eric R. (2022). "Pectoralis Minor Syndrome – Review of Pathoanatomy, Diagnosis, and Management of the Primary Cause of Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome". JSES Reviews, Reports, and Techniques: S2666639122000694. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2022.05.008. PMC 10426640.

- ^ a b Anderson, D.M. (2000). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (29th edition). Philadelphia/London/Toronto/Montreal/Sydney/Tokyo: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ^ Dorland, W.A.N. & Miller, E.C.L. (1948). The American illustrated medical dictionary. (21st edition). Philadelphia/London: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ^ Dirckx, J.H. (Ed.) (1997).Stedman's concise medical dictionary for the health professions. (3rd edition). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT) (1998). Terminologia Anatomica. Stuttgart: Thieme

- ^ a b c Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- Nickel, Schummer, & Seiferle; Lehrbuch der Anatomie der Haussäugetiere.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo:10:st-0301 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Joints of the Upper Extremity: Scapula"

- shoulder/bones/bones2 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

- shoulder/surface/surface2 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

- radiographsul at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (xrayleftshoulder)

Scapula

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Surfaces

The costal surface, also known as the anterior or ventral surface, faces the thoracic rib cage and features a large, shallow concavity known as the subscapular fossa.[2] This fossa occupies most of the surface and is relatively smooth in texture, with three longitudinal ridges that traverse it for structural support.[2] The dorsal surface, or posterior surface, is convex and marked by a prominent bony ridge called the spine of the scapula, which divides it into two fossae of unequal size.[2] The supraspinous fossa lies superior to the spine and is smaller and more triangular in outline, while the infraspinous fossa below is larger and extends toward the inferior angle; both fossae exhibit a roughened texture.[2] A subtle ridge runs along the medial aspect of the infraspinous fossa near the lateral border, originating from the glenoid cavity and terminating above the inferior angle.[2] The lateral surface, situated at the lateral angle of the scapula, encompasses the glenoid cavity and transitions into a narrow neck connecting the cavity to the body of the bone.[2] The glenoid cavity itself is pear-shaped and shallow, serving as the articulation site for the humerus, with its orientation featuring a slight upward tilt of 10 to 15 degrees relative to the medial border of the scapula.[3][4] In adults, the scapula measures an average length of approximately 14.8 cm and width of 10.8 cm, contributing to its overall triangular morphology with a subtle lateral curvature that aligns the glenoid for shoulder mobility.[5][6]Borders

The scapula is bounded by three distinct borders that form its triangular perimeter: the medial (vertebral) border, the lateral (axillary) border, and the superior border. These edges vary in length, thickness, and curvature, contributing to the bone's structural integrity and mobility within the shoulder girdle.[2] The medial border, also known as the vertebral border, is the longest of the three, measuring approximately 15 cm in adults, and runs parallel to the vertebral column along the dorsal aspect of the thorax. It is relatively straight or slightly convex, extending continuously from the superior angle to the inferior angle without major interruptions, and provides attachment sites for muscles including the levator scapulae superiorly and the rhomboid muscles along its length (detailed attachments covered separately).[2][7] The lateral border, or axillary border, is the thickest and most robust, with a length of about 12-14 cm, and exhibits a rounded, slightly concave profile that accommodates surrounding musculature. Positioned along the axillary region, it extends from the inferior angle superolaterally toward the glenoid cavity, forming a sturdy lateral margin that supports the articulation with the humerus.[2][8] The superior border is the shortest and thinnest, typically measuring 5-6 cm, and presents a concave curvature that arches gently from the superior angle to the base of the coracoid process. It features the suprascapular notch, a prominent indentation near its lateral end that is bridged by the superior transverse scapular ligament to form the suprascapular foramen.[2][7] These borders interconnect at the scapula's angles to delineate its overall triangular outline, with the medial and superior borders meeting superiorly, the superior and lateral borders converging laterally, and the medial and lateral borders uniting inferiorly, thereby enclosing the bone's dorsal and costal surfaces.[2]Angles

The scapula, a flat triangular bone, features three distinct angles that serve as key junction points between its borders, contributing to its overall structural framework and facilitating muscle attachments and joint articulation. These angles are the superior, inferior, and lateral, each with unique morphological characteristics and positional alignments that underscore their roles in shoulder girdle stability.[2] The superior angle is an acute, rounded projection located at the junction of the superior and medial borders, positioned near the level of the T2 vertebra. This angle provides a smooth insertion site for the levator scapulae muscle, which aids in elevating the scapula.[9][10][8] The inferior angle, the largest and most prominent of the three, is a blunt, rounded structure situated at the junction of the medial and lateral borders, aligning with the T7 vertebral level. It serves as a palpable surface landmark on the back, often used in clinical assessments for its superficial position over the seventh rib.[11][12] The lateral angle is a thick, robust region formed at the junction of the superior and lateral (axillary) borders, where it expands to create the glenoid fossa—a shallow cavity that articulates with the humerus to form the glenohumeral joint. This thickening enhances the structural integrity required for weight-bearing and mobility at the shoulder.[13][8] Collectively, the superior and inferior angles are positioned along the medial border, while the lateral angle lies at the axillary border, delineating the scapula's characteristic triangular outline and distributing mechanical stresses across the bone.[2]Processes

The scapula possesses several key bony processes that project from its body, serving primarily as structural supports and sites for articulation with adjacent bones. These include the spine, acromion, coracoid, and glenoid cavity, each with distinct shapes and positions that contribute to the overall architecture of the shoulder girdle.[2] The spine of the scapula is a prominent, transverse ridge that extends obliquely across the posterior surface of the bone, separating the supraspinous and infraspinous fossae. It originates near the medial border and runs laterally toward the acromion, providing a robust division of the dorsal aspect. This ridge-like structure typically measures around 10 cm in length in adults, though exact dimensions vary.[14][15] The acromion process forms as a flattened, oblong lateral extension of the scapular spine, projecting anteriorly and laterally to create the summit of the shoulder. Located superior to the glenoid cavity, it is a broad, flat projection that averages approximately 4.5 cm in length and 2.4 cm in width in adult scapulae. Articularly, the acromion connects with the lateral end of the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint, forming part of the shoulder arch.[2][14][15][6] The coracoid process arises as a hook-like projection from the superior lateral aspect of the scapular neck, directed anteriorly and slightly laterally, resembling a crow's beak. Positioned inferior to the clavicle and lateral to the suprascapular notch, its overall length averages about 4.4 cm, with the terminal hook measuring roughly 1.4 cm in width. While it does not form a direct synovial joint, the coracoid serves as a key anchor in the pectoral girdle.[2][14][15][6] The glenoid process, often referred to as the glenoid cavity or fossa, is an oval-shaped, pear-like depression located at the lateral angle of the scapula, at the junction of the superior and lateral borders. This shallow cavity is oriented laterally and slightly superiorly, with average dimensions of 3.6 cm in the superior-inferior direction and 2.5 cm in the anterior-posterior direction; it is deepened by the fibrocartilaginous glenoid labrum to enhance stability. Articularly, the glenoid cavity forms the glenohumeral joint by receiving the head of the humerus, allowing for a wide range of shoulder motion.[2][14][15][6]Muscle and ligament attachments

The scapula serves as a key site for the origin and insertion of multiple muscles involved in shoulder girdle stability and movement, as well as the attachment of several ligaments that reinforce the glenohumeral joint and connect to adjacent bones. These attachments occur on specific bony features such as the fossae, borders, angles, spine, acromion, and coracoid process, often marked by roughened surfaces or tubercles that facilitate secure tendinous bonds. Distinguishing between origins (where muscles arise from the scapula) and insertions (where muscles attach to the scapula after originating elsewhere) is essential for understanding the bone's role in musculoskeletal architecture.[2] Among the muscles originating from the scapula, the subscapularis arises from the subscapular fossa on the costal (anterior) surface, covering much of this concave area with its broad aponeurosis. The supraspinatus originates from the supraspinous fossa above the spine, utilizing the smooth, concave region for its fleshy belly. Similarly, the infraspinatus takes origin from the infraspinous fossa below the spine, attaching across the larger posterior depression. The teres minor originates along the upper two-thirds of the lateral (axillary) border, near the infraglenoid tubercle, on a roughened area that supports its tendon. The teres major originates from the inferior angle and the lower part of the lateral border, at the dorsal surface where the bone tapers. The deltoid originates from the lateral aspect of the spine and the inferior surface of the acromion, with fibers blending into the trapezius insertion nearby. The short head of the biceps brachii originates from the coracoid process, specifically the lateral aspect of its tip, alongside the coracobrachialis. These origins are typically characterized by roughened periosteum to enhance tendon adhesion.[2][8][16] Muscles inserting onto the scapula include the rhomboid major and minor, which attach to the medial (vertebral) border; the major to the medial border from the spine to the inferior angle, and the minor to the upper portion at the base of the spine, both on roughened strips that allow for their tendinous insertions. The trapezius inserts along the medial third of the spine, the acromion, and the posterior aspect of the lateral clavicle, with upper fibers attaching superiorly. The pectoralis minor inserts onto the medial aspect of the coracoid process, its three-digit tendon fanning out over the roughened surface. These insertions contribute to scapular retraction and elevation, with the medial border featuring distinct ridges for rhomboid attachment.[2][8] Key ligaments associated with the scapula include the coracoacromial ligament, which extends from the lateral border of the coracoid process to the acromion, forming a strong fibrous arch over the suprahumeral space. The coracoclavicular ligament, comprising the trapezoid (lateral) and conoid (medial) parts, attaches from the coracoid process to the inferior surface of the clavicle, providing vertical stability to the acromioclavicular joint. The superior transverse scapular ligament bridges the suprascapular notch, converting it into the scapular foramen through which the suprascapular nerve passes, anchored to the bony margins superior to the notch. These ligaments originate or insert directly on scapular processes, often at sites with thickened periosteum for enhanced tensile strength.[2][8]Blood supply and innervation

The arterial supply to the scapula is derived from the scapular anastomosis, a network that ensures robust collateral circulation around the bone and its attachments. The suprascapular artery, originating from the thyrocervical trunk (a branch of the subclavian artery), courses superiorly over the superior transverse scapular ligament or through the suprascapular notch to supply the supraspinatus fossa, infraspinatus fossa, and acromion.[1] The subscapular artery, arising from the third part of the axillary artery, descends along the posterior axillary wall and gives off the circumflex scapular artery, which pierces the triangular space to reach the posterior scapular surface and contribute to the anastomosis near the lateral border.[1] Complementing these, the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries—both branches of the axillary artery—encircle the surgical neck of the humerus and provide blood to the glenoid cavity, glenohumeral joint capsule, and adjacent scapular margins.[17] Venous drainage parallels the arterial pathways, with blood from the scapular region collecting into the suprascapular and circumflex scapular veins, which ultimately converge into the axillary vein; this system includes numerous small, variable anastomotic tributaries that facilitate efficient return flow.[1] Innervation of the scapula and its attached musculature primarily involves motor nerves from the brachial plexus, with sensory contributions to the overlying skin and periosteum. The suprascapular nerve, derived from the C5 and C6 spinal roots via the superior trunk, enters the supraspinatus fossa through the suprascapular notch (beneath the superior transverse scapular ligament) to innervate the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.[18] The axillary nerve, also from C5 and C6 roots off the posterior cord, wraps around the surgical neck of the humerus near the glenoid to supply motor innervation to the teres minor muscle and sensory branches to the shoulder joint capsule.[19] Along the medial border, the dorsal scapular nerve (C5 root) provides motor supply to the rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and levator scapulae muscles.[20] Sensory innervation to the scapular periosteum and posterior thoracic skin is mediated by branches of the lateral pectoral nerve (from C5-T1) and the second to fourth intercostal nerves (from thoracic spinal nerves T2-T4).[1] The intraosseous blood supply enters the scapula via nutrient foramina, small vascular channels typically located along the medial and lateral borders as well as the costal and dorsal surfaces, with studies identifying an average of 5.3 such foramina per scapula to support endosteal nutrition and bone remodeling.[21]Development

The scapula originates from the lateral plate mesoderm as part of the pectoral girdle during embryonic development. In the fifth week of gestation, it appears as a mesenchymal condensation proximal to the developing upper limb bud, initially forming an irregular structure with outgrowths corresponding to the future body, coracoid process, and glenoid region.[22][23] This condensation differentiates under the influence of signaling pathways, such as those involving fibroblast growth factors and Wnt, to establish the foundational framework for the scapular blade and articulating surfaces.[24] Ossification of the scapula primarily occurs through intramembranous ossification, with a primary center appearing in the body around the eighth week of intrauterine life.[25][26] Secondary ossification centers develop postnatally: the coracoid process ossifies from two centers, the first appearing around 1 year of age and the second between 6 and 10 years; the acromion forms from up to three centers that appear variably from birth to late adolescence (typically 14-18 years); and the glenoid cavity ossifies from centers emerging between birth and 14 years, contributing to the subglenoid and coracoid regions.[25][27] These centers gradually fuse with the primary body ossification site, completing by approximately 25 years of age, though variations can persist.[28] Postnatal growth of the scapula involves appositional bone deposition along its periosteal surfaces, allowing expansion in size and adaptation to increasing mechanical loads from upper limb activity.[29] This process is modulated by mechanical stress, in accordance with Wolff's law, where bone remodeling strengthens areas subjected to tension or compression from muscle attachments and joint forces.[30] Sexual dimorphism emerges during growth, with male scapulae typically achieving greater overall dimensions—such as longer blades and wider glenoids—compared to females, reflecting differences in body size and hormonal influences on skeletal maturation.[31] Incomplete fusion of secondary centers, particularly the acromion, may result in os acromiale, a developmental variant observed in 1-15% of individuals.[32]Function

Movements

The scapula exhibits a variety of movements that facilitate the extensive mobility of the shoulder girdle and upper extremity. These include elevation and depression, which involve superior and inferior translation; protraction and retraction, which describe anterior and posterior gliding along the thoracic wall; upward and downward rotation, which adjust the orientation of the glenoid fossa; and anterior and posterior tilting, which fine-tune the scapula's position relative to the thorax. These motions collectively enable the shoulder to achieve full functional range, such as overhead reaching or pushing activities.[1] Normal ranges for these movements vary slightly across individuals but are well-characterized in healthy adults. Elevation typically allows for up to 40 degrees of superior displacement, while depression permits about 10 degrees of inferior movement. Protraction and retraction occur with ranges of approximately 20 degrees and 15 degrees, respectively, reflecting the scapula's sliding over the curved thoracic surface. Upward rotation spans 30 to 60 degrees during arm abduction beyond 90 degrees, and downward rotation mirrors this range in reverse. Anterior tilting averages 10 to 20 degrees, whereas posterior tilting can reach 20 to 30 degrees, particularly during overhead arm positions to accommodate humeral head clearance. Full arm elevation to 180 degrees necessitates about 60 degrees of upward rotation to supplement glenohumeral motion.[33][34][35] These movements are enabled primarily by the scapulothoracic articulation, a physiological joint formed by the muscular and fascial gliding of the scapula's posterior surface against the thoracic wall, without bony congruence. Optimal scapular gliding requires a smooth underlying thoracic surface and a well-contoured, mobile rib cage; deviations from these conditions can impair shoulder function by disrupting normal scapulohumeral rhythm and increasing friction or instability, which may be addressed through posture correction, mobility exercises, or strengthening of scapular stabilizers.[36][37] Additional mobility is provided indirectly through the acromioclavicular joint, linking the acromion to the clavicle, and the sternoclavicular joint, connecting the clavicle to the manubrium, allowing coupled translation and rotation of the entire girdle.[1][33] Coordinated muscle action drives and stabilizes these motions. The upper trapezius and levator scapulae elevate the scapula, while the lower trapezius, serratus anterior (lower fibers), pectoralis minor, and latissimus dorsi depress it.[38] Protraction is primarily achieved by the serratus anterior and pectoralis minor, with retraction facilitated by the middle/lower trapezius and rhomboid major and minor. Upward rotation involves synergistic action of the upper and lower trapezius with the serratus anterior, whereas downward rotation is powered by the rhomboids, levator scapulae, and pectoralis minor. These muscles ensure smooth integration with humeral movements for efficient shoulder function. In strength training and resistance exercises, deliberate scapular depression is commonly cued (often as "sink" or "pack" the shoulders) to engage the latissimus dorsi and lower trapezius, stabilize the shoulder joint and girdle, prevent excessive upper trapezius activation leading to shrugging, reduce the risk of shoulder impingement, and promote optimal posture and form. This cue is particularly emphasized in pulling exercises (e.g., pull-ups, rows), deadlifts, and overhead movements to ensure proper muscle activation, shoulder health, and performance.[36]Biomechanics

The scapula functions as a critical strut in the shoulder girdle, connecting the humerus via the glenohumeral joint to the clavicle through the acromioclavicular joint, thereby facilitating the transmission of upper limb loads to the axial skeleton via the sternoclavicular joint. This configuration allows the scapula to distribute compressive and shear forces generated during arm activities, such as lifting or pushing, across the thoracic cage while maintaining mobility. In this role, the scapula's broad, triangular shape and muscular attachments enable it to act as a mechanical lever, converting upper extremity forces into controlled motion and stability against the thorax. Stability of the scapula within the shoulder complex relies on both static and dynamic mechanisms to counteract translational and rotational forces. Static stabilizers include the glenoid labrum, which deepens the glenoid fossa by 50% and enhances concavity for humeral head containment, and the glenohumeral ligaments (superior, middle, and inferior), which provide passive restraint against excessive translation, particularly in abduction and external rotation. Dynamic stability is primarily achieved through the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis), which generate compressive forces to center the humeral head in the glenoid, with peak contributions from the subscapularis (up to 53% of total cuff force) during loading. Scapular stabilizers like the serratus anterior and trapezius further contribute dynamically by forming force couples that prevent scapular winging and maintain thoracic alignment.[39][40][41] A key biomechanical principle governing scapular motion is the scapulohumeral rhythm, which describes the coordinated ratio of glenohumeral to scapulothoracic movement during elevation, typically 2:1 in abduction beyond 30° (i.e., for every 2° of humeral elevation, the scapula upwardly rotates 1°). This rhythm ensures optimal glenohumeral joint congruency and minimizes impingement by progressively orienting the glenoid upward and posteriorly. The 2:1 ratio arises from the initial 30° of pure glenohumeral motion followed by coupled scapular upward rotation, posterior tilt, and external rotation, driven by balanced muscle forces from the deltoid, trapezius, and serratus anterior. Stress analysis reveals significant loads on the scapula during overhead activities, with glenohumeral compressive forces reaching 0.8–1.5 times body weight (BW) in throwing motions, such as the post-release deceleration phase where forces approximate 1090 N (∼1.55 BW for a 70 kg individual). These compressive loads are transmitted through the scapula to the clavicle, peaking during arm cocking and acceleration to stabilize the joint against superior migration. Along the scapulothoracic interface, shear forces arise from frictional sliding of the scapula against the thoracic wall, with anterior-posterior shear-to-compression ratios up to 0.42 during shoulder-level lifts, potentially exacerbated by muscle imbalances leading to scapular protraction or retraction.[42][43] Alterations in scapulohumeral rhythm, such as reduced upward rotation (by 5–15° in affected individuals), can disrupt force distribution and contribute to subacromial impingement by narrowing the subacromial space and increasing humeral head proximity to the coracoacromial arch.[35]Clinical significance

Fractures and injuries

Scapular fractures are uncommon injuries, comprising less than 1% of all fractures and 3-5% of shoulder girdle fractures, typically resulting from high-energy blunt trauma such as motor vehicle collisions or falls from height.[44] These fractures occur in 80-90% of cases due to direct impact on the scapula or indirect force from humeral head impaction into the glenoid, and approximately 90% are associated with concomitant injuries, including rib fractures, clavicular fractures, pulmonary contusions, or head trauma.[45] Neurovascular compromise, such as brachial plexus injury, affects 10-20% of patients, underscoring the need for thorough assessment.[46] Fractures are classified by anatomic location, with body fractures being the most common (about 45%), often involving transverse or oblique patterns from direct blows and rarely requiring intervention unless severely displaced.[44] Scapular neck fractures are distinguished as anatomic (proximal to the glenoid) or surgical (distal, involving the glenoid neck), where surgical necks may necessitate fixation if there is greater than 1 cm translation or 40° angulation to restore shoulder stability.[45] Glenoid rim fractures, frequently anterior or posterior avulsions, demand attention due to potential glenohumeral instability, particularly if the articular step-off exceeds 2 mm or involves more than 20-25% of the glenoid surface.[47] Acromion fractures, graded I-III by displacement, and coracoid process avulsions (often from muscle pull) are less frequent (8% and 7%, respectively), with type III acromion or significantly displaced coracoid fractures typically treated surgically to prevent impingement or nonunion.[44] Diagnosis begins with a history of high-energy trauma and physical examination revealing localized pain, swelling, crepitus, and restricted shoulder motion, alongside evaluation for associated injuries.[46] Standard anteroposterior and lateral scapular radiographs detect most fractures, but computed tomography (CT) is essential for assessing displacement, intra-articular involvement, and surgical planning, as initial chest X-rays miss up to 43% of cases.[45] Management is predominantly conservative for over 90% of nondisplaced or minimally displaced fractures, involving sling immobilization for 1-3 weeks followed by early pendulum exercises and physical therapy to promote healing and prevent stiffness.[44] Surgical intervention, such as open reduction and internal fixation, is indicated for displaced glenoid fractures with more than a 2 mm step-off, significant neck angulation, open fractures, or floating shoulder variants to ensure articular congruity and functional recovery.[47] In select cases, fractures may briefly disrupt local blood supply, though vascular integrity is generally preserved due to the scapula's robust muscular envelope.[46]Congenital anomalies

Congenital anomalies of the scapula encompass a range of developmental malformations arising from disruptions in embryonic formation and migration, leading to structural abnormalities that can impair shoulder function and aesthetics. Sprengel's deformity, the most common congenital anomaly of the scapula, involves an abnormally high or undescended scapula resulting from incomplete caudal migration during the fifth to eighth weeks of gestation.[48] This condition is characterized by a small, rotated scapula positioned above the typical level at the seventh cervical vertebra, often with associated omovertebral bone connecting the scapula to the cervical spine.[49] It presents unilaterally in approximately 80% of cases, more frequently on the right side, and may cause visible asymmetry, limited shoulder abduction, and scapular winging.[50] Sprengel's deformity is frequently associated with Klippel-Feil syndrome, occurring in 20-42% of those cases due to shared disruptions in somitogenesis and Hox gene expression. Scapular dysgenesis refers to partial absence, hypoplasia, or malformation of the scapula, stemming from faulty mesodermal differentiation in early embryogenesis.[51] This anomaly can occur in isolation or as part of multisystem genetic disorders. Isolated cases may present with unilateral or bilateral involvement, resulting in reduced scapular size and altered muscle attachments that limit arm elevation. Os acromiale represents a failure of fusion of one or more acromial ossification centers, a congenital variation occurring during postnatal growth between ages 14 and 18.[52] It has a prevalence of 2-8% in the general population, with higher rates (up to 15%) in individuals of African descent, and involves segments such as the meta-acromion or pre-acromion remaining separate. Most cases are asymptomatic, but a mobile os acromiale can cause subacromial impingement, pain, and rotator cuff irritation due to abnormal motion at the unfused site.[53] Diagnosis of these anomalies begins prenatally with ultrasound, which can identify elevated scapular position or hypoplasia in high-risk pregnancies, though sensitivity is limited by fetal positioning.[54] Postnatally, plain radiographs confirm scapular position and bony connections, while MRI delineates soft tissue involvement, cartilage, and associated spinal anomalies; CT is reserved for detailed omovertebral bone assessment.[55] Treatment is conservative for mild cases, focusing on physical therapy to improve range of motion. Surgical intervention, such as the Woodward procedure for Sprengel's deformity, involves scapular osteotomy, excision of the omovertebral bone, and muscle transfer to achieve caudal descent, typically performed between ages 3 and 8 for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes.[49] For symptomatic os acromiale, fusion or excision is indicated, while scapular dysgenesis management addresses underlying syndromes supportively.[52]Other disorders

Scapular winging refers to the abnormal prominence of the medial border of the scapula due to dysfunction in the muscles that stabilize it against the thoracic wall. Medial winging most commonly arises from serratus anterior muscle palsy, typically resulting from injury to the long thoracic nerve, which innervates this muscle and can be affected by trauma, iatrogenic causes, or idiopathic neuritis.[56] Trapezius weakness, often due to accessory nerve injury, leads to lateral winging characterized by inferior and lateral displacement of the scapula, impairing shoulder elevation and stability.[57] This condition manifests as pain, weakness, and limited range of motion during overhead activities, with prevalence estimated at 1-10% among patients with brachial plexus injuries, where nerve involvement contributes to the imbalance.[58] Optimal scapular gliding requires a smooth underlying thoracic surface provided by the subscapularis and serratus anterior muscles, along with a well-contoured and mobile rib cage to serve as a stable base for movement; deviations such as surface irregularities, reduced thoracic mobility, or muscle imbalances impair shoulder function by disrupting scapulothoracic rhythm, leading to pain, instability, and diminished range of motion.[36][59] These impairments contribute to various disorders and are primarily managed through conservative approaches, including posture correction to optimize alignment, mobility exercises to enhance thoracic and rib cage flexibility, and strengthening of scapular stabilizers to restore efficient gliding mechanics.[36] Osteochondromas are benign bone tumors that frequently develop at the borders or processes of the scapula and are the most common benign tumor affecting the scapula. These exophytic lesions arise from aberrant cartilage growth, though they account for a smaller fraction of all osteochondromas overall. Symptomatic cases, which may present with pain, mechanical symptoms, or restricted motion due to mass effect, are managed through surgical excision to alleviate symptoms and prevent complications such as bursal irritation or malignant transformation, which occurs in less than 2% of cases with complete resection.[60][61] Arthritic conditions involving the scapula include glenohumeral osteoarthritis, which alters scapular alignment and kinematics, leading to compensatory protraction and upward rotation abnormalities that exacerbate pain and dysfunction. In advanced stages, this degenerative process erodes the glenoid fossa, shifting the humeral head and disrupting scapulothoracic rhythm. Additionally, scapulothoracic bursitis, often termed crepitus syndrome, involves inflammation of the bursae between the scapula and thoracic wall, resulting in audible or palpable grinding during scapular motion due to repetitive friction or soft tissue hypertrophy.[62][63] Snapping scapula syndrome describes abnormal scapular motion producing audible or palpable snapping, grinding, or crepitus, stemming from bony irregularities such as exostoses or soft tissue anomalies like bursitis or muscle atrophy. This condition disrupts normal scapulothoracic gliding and is often linked to repetitive overhead activities or prior trauma. Initial management is conservative, incorporating physical therapy to strengthen periscapular muscles, anti-inflammatory medications, and activity modification, with surgical intervention—such as bursectomy or bony decompression—reserved for refractory cases to restore smooth articulation.[64]Comparative anatomy

In other mammals

In quadrupedal mammals such as dogs and horses, the scapula exhibits a more horizontal orientation compared to the vertical positioning in humans, facilitating greater mobility along the rib cage to support weight-bearing during locomotion.[65] This lateral positioning allows the scapula to slide and rotate freely without bony articulation, contributing significantly to stride length in horses by enabling protraction and retraction of the forelimb.[66] The scapular spine is elongated and prominent, extending from the dorsal border to enhance muscle attachments for trunk support, while the glenoid cavity shows reduced cranial inclination, orienting more caudally to distribute compressive forces from the forelimbs, which bear approximately 60% of body weight in static stance.[65][67] Among primates, the scapula in apes and gibbons displays adaptations closer to humans but with modifications for suspensory behaviors like brachiation, featuring a broader overall structure to accommodate powerful shoulder rotators and flexors.[68] In gibbons, the scapula is axially elongated with a cranially oriented glenoid cavity and increased breadth, promoting superior and lateral glenoid rotation during arm-swinging to maximize reach and stability in arboreal environments.[68] This contrasts with the narrower human scapula, where the glenoid faces more laterally for overhead arm elevation in bipedal posture.[68] Scapular variations across mammals reflect locomotor demands, with carnivores like felids possessing a prominent acromion process that extends ventrally for enhanced deltoid leverage during agile pursuits and climbing.[69] In herbivores such as horses and tapirs, the scapula is generally larger and more robust, providing greater surface area for muscle origins to ensure stability under high body mass and sustained weight-bearing.[70][65] Specialized mammals exhibit further adaptations; in bats, the scapula functions as a connecting rod in the shoulder girdle, undergoing anteroposterior shifts in the frontal plane during flight to synchronize with clavicular rotation and humerus excursion, though it is not markedly elongated relative to body size.[71] In cetaceans like whales, the scapula remains a distinct yet robust element of the pectoral girdle, supporting the immobilized flipper as a hydrofoil for hydrodynamic stability without fusion to adjacent bones, but with strong muscular attachments like the triceps brachii caput longum originating from its caudal border.[72]In non-mammals

In non-mammalian vertebrates, the scapula exhibits significant variation reflecting diverse locomotor demands and evolutionary histories. In fish, the pectoral girdle primarily consists of dermal bones such as the cleithrum and supracleithrum, with the scapula represented as a rudimentary endochondral element or entirely absent in some primitive forms, serving mainly as a small cartilaginous support for the pectoral fin rays.[73] This configuration underscores the girdle's origin from intramembranous ossification in the dermal armor of early osteichthyans, where the endochondral scapula evolves later to anchor fin musculature.[74] In amphibians, the scapula remains small and cartilaginous in larvae, ossifying partially in adults as a thin, triangular plate fused proximally to the coracoid, but it lacks the robust structure seen in more derived tetrapods due to the girdle's reliance on persistent dermal components like the clavicle and interclavicle for stability during terrestrial transitions.[75] Among reptiles, the scapula is typically small and triangular, particularly in lizards (Lacertilia), where it fuses with the coracoid in adulthood to form a compact scapulocoracoid unit.[76] This fusion creates the supracoracoid fenestra, a perforation in the coracoid through which the tendon of the supracoracoideus muscle passes to facilitate forelimb elevation and retraction, essential for crawling and burrowing locomotion in forms like the horned lizard (Phrynosoma).[77] In broader reptilian diversity, such as crocodilians, the scapula remains separate from the coracoid via a suture but shares the glenoid fossa, allowing greater mobility while maintaining structural integrity for semiaquatic propulsion.[76] In birds, the scapula is highly reduced to a slender, flat plate-like structure, which articulates tightly with the elongated coracoid to form a rigid brace for the wing.[78] This scapulocoracoid configuration, fused at the glenoid in many species, creates the triosseal canal—a key flight adaptation where the supracoracoideus muscle tendon passes to power the wing's upstroke, while the pectoralis drives the downstroke.[78] For example, in eagles (Aquila spp.), the strut-like assembly withstands aerodynamic forces during soaring and diving, with the coracoid's brace-like elongation distributing stress across the keel of the sternum for efficient powered flight.[79] Among dinosaurs, scapular morphology diverged markedly between major clades to support bipedal or quadrupedal gaits. In theropods, such as Tyrannosaurus rex, the scapula is elongated and blade-like, with a strap-shaped distal portion up to 82 cm long in large specimens, oriented nearly horizontally relative to the vertebral column to enhance forelimb reach and stability during predatory lunges.[80] Fossil evidence from Allosaurus fragilis confirms this pattern, providing leverage for the reduced but muscular forelimbs in bipedal locomotion.[81] In contrast, ornithischians exhibit broader, more fan-shaped scapulae for enhanced weight-bearing and stability, particularly in quadrupedal forms like ceratopsians and hadrosauroids, where the vertically inclined blade with a distal kink distributes forelimb load across a wider surface during grazing or charging.[82] This robust design, evident in basal ornithopods like Thescelosaurus, contrasts with the slender theropod form by prioritizing postural support over agility.[83]Evolutionary aspects

The origins of the scapula trace back to the dermal pectoral girdle in early vertebrates, with the earliest evidence appearing in jawless fish approximately 430 million years ago (mya), where it served as an anchor to the dermal bones of the head.[24] In sarcopterygian fish around 400 mya during the Devonian period, the structure began incorporating endoskeletal elements, supporting the robust paired fins that presaged the fin-to-limb transition.[84] This evolutionary progression transformed the scapula into the primary endoskeletal component of the pectoral girdle in early tetrapods by approximately 373 mya, facilitating the shift from aquatic to terrestrial locomotion.[85] Key transitions in scapular morphology occurred across major vertebrate clades. In amphibians, the scapula adopted a ventrally attached, free-floating configuration without direct bony linkage to the axial skeleton, relying instead on muscular suspension for stability during early terrestrial movement.[24] Reptiles further refined this to a predominantly free-floating, dorsally positioned form, integrating dermal and endoskeletal components to support diverse locomotor modes such as sprawling gait.[86] In mammals, the emergence of a prominent dorsal blade enhanced scapular mobility, complemented by ventral attachment through the clavicle to the sternum, allowing greater forelimb excursion.[24] Birds represent a specialized adaptation, with the scapula fusing proximally to the sternal keel, optimizing muscle leverage for powered flight while maintaining dorsal positioning over the ribcage.[87] Within primates, the scapula exhibited notable adaptations, including increased size and enhanced glenohumeral joint mobility to accommodate arboreal suspension and manipulative behaviors associated with tool use.[24] Fossil evidence from Australopithecus afarensis, such as the juvenile scapulae from the Dikika site in Ethiopia dating to about 3.3 mya, reveals ape-like traits including a superiorly oriented glenoid fossa and elongated supraspinous fossa, indicative of retained climbing capabilities alongside emerging bipedalism.[88] By approximately 4 mya in early hominins like Australopithecus anamensis, scapular proportions began approaching modern human-like configurations, with a laterally facing glenoid and broader blade supporting overhead arm positions.[89] This gradual refinement reflects selective pressures for improved shoulder flexibility in open habitats. Functionally, the scapula transitioned from a primary weight-bearing role in quadrupeds—transmitting forelimb forces to the axial skeleton during terrestrial support—to a pendular mechanism in bipeds, enabling rhythmic arm swing and elevated reach for foraging and manipulation.[90] In quadrupedal primates, the cranially oriented acromion and narrower blade prioritized stability and propulsion, whereas bipedal hominins evolved a more lateral acromion and expanded infraspinous fossa to facilitate rotator cuff efficiency and throwing motions.[24] These shifts, occurring over the past 6–8 million years, profoundly influenced shoulder girdle evolution by emphasizing versatility over load distribution.[89]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Osteology_of_the_Reptiles/Chapter_4