Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

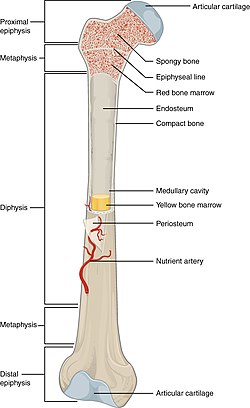

| Bone | |

|---|---|

A bone dating from the Pleistocene Ice Age of an extinct species of elephant | |

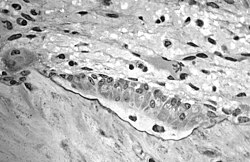

A scanning electronic micrograph of bone at 10,000× magnification | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D001842 |

| TA98 | A02.0.00.000 |

| TA2 | 366, 377 |

| TH | H3.01.00.0.00001 |

| FMA | 5018 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals.[1] Bones protect the organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, help regulate acid-base homeostasis, provide structure and support for the body, and enable mobility and hearing. Bones come in a variety of shapes and sizes and have complex internal and external structures.[2]

Bone tissue (also known as osseous tissue or bone in the uncountable) is a form of hard tissue, specialised connective tissue that is mineralized and has an intercellular honeycomb-like matrix,[3] which helps to give the bone rigidity. Bone tissue is made up of different types of bone cells: osteoblasts and osteocytes (bone formation and mineralisation); osteoclasts (bone resorption); modified or flattened osteoblasts (lining cells that form a protective layer on the bone surface). The mineralised matrix of bone tissue has an organic component of mainly ossein, a form of collagen, and an inorganic component of bone mineral, made up of various salts. Bone tissue comprises cortical bone and cancellous bone, although bones may also contain other kinds of tissue including bone marrow, endosteum, periosteum, nerves, blood vessels, and cartilage.

In the human body at birth, approximately 300 bones are present. Many of these fuse together during development, leaving a total of 206 separate bones in the adult, not counting numerous small sesamoid bones.[4][5] The largest bone in the body is the femur or thigh-bone, and the smallest is the stapes in the middle ear.

The Ancient Greek word for bone is ὀστέον ("osteon"). In anatomical terminology, including in the Terminologia Anatomica, the word for a bone is os (for example, os breve, os longum, os sesamoideum).

Gross anatomy

[edit]Five types of bones are found in the human body: long, short, flat, irregular, and sesamoid.[6]

- Long bones are characterized by a shaft, the diaphysis, that is much longer than its width; and by an epiphysis, a rounded head at each end of the shaft. They are made up mostly of compact bone, with lesser amounts of marrow, located within the medullary cavity, and areas of spongy, cancellous bone at the ends of the bones.[7]

- Most bones of the limbs, including those of the fingers and toes, are long bones. The exceptions are the eight carpal bones of the wrist, the seven articulating tarsal bones of the ankle and the sesamoid bone of the kneecap. Long bones such as the clavicle, that have a differently shaped shaft or ends are also called modified long bones.

- Short bones are roughly cube-shaped, and have only a thin layer of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. Short bones provide stability and support as well as some limited motion.[8]

- The bones of the wrist and ankle are short bones.

- Flat bones are thin and generally curved, with two parallel layers of compact bone sandwiching a layer of spongy bone.

- Sesamoid bones are bones embedded in tendons. Since they act to hold the tendon further away from the joint, the angle of the tendon is increased and thus the leverage of the muscle is increased.

- Irregular bones do not fit into the above categories. They consist of thin layers of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. As implied by the name, their shapes are irregular and complicated. Often this irregular shape is due to their many centers of ossification or because they contain bony sinuses.

Terminology

[edit]

Anatomists use a number of anatomical terms to describe the appearance, shape and function of bones. Like other anatomical terms, many of these derive from Latin and Greek. Some anatomists still use Latin to refer to bones. The term "osseous", and the prefix "osteo-", referring to things related to bone, are still used commonly today.

Some examples of terms used to describe bones include the term "foramen" to describe a hole through which something passes, and a "canal" or "meatus" to describe a tunnel-like structure. A protrusion from a bone can be called a number of terms, including a "condyle", "crest", "spine", "eminence", "tubercle" or "tuberosity", depending on the protrusion's shape and location. In general, long bones are said to have a "head", "neck", and "body".

When two bones join, they are said to "articulate". If the two bones have a fibrous connection and are relatively immobile, then the joint is called a "suture".

Functions

[edit]Mechanical

[edit]Bones serve a variety of mechanical functions. Together the bones in the body form the skeleton. They provide a frame to keep the body supported, and an attachment point for skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints, which function together to generate and transfer forces so that individual body parts or the whole body can be manipulated in three-dimensional space (the interaction between bone and muscle is studied in biomechanics).

Bones protect internal organs, such as the skull protecting the brain or the ribs protecting the heart and lungs. Because of the way that bone is formed, bone has a high compressive strength of about 170 MPa (1,700 kgf/cm2),[12] poor tensile strength of 104–121 MPa, and a very low shear stress strength (51.6 MPa).[13][14] This means that bone resists pushing (compressional) stress well, resist pulling (tensional) stress less well, but only poorly resists shear stress (such as due to torsional loads). While bone is essentially brittle, bone does have a significant degree of elasticity, contributed chiefly by collagen.

Mechanically, bones also have a special role in hearing. The ossicles are three small bones in the middle ear which are involved in sound transduction.

Synthetic

[edit]The cancellous part of bones contain bone marrow. Bone marrow produces blood cells in a process called hematopoiesis.[15] Blood cells that are created in bone marrow include red blood cells, platelets and white blood cells.[16] Progenitor cells such as the hematopoietic stem cell divide in a process called mitosis to produce precursor cells. These include precursors which eventually give rise to white blood cells, and erythroblasts which give rise to red blood cells.[17] Unlike red and white blood cells, created by mitosis, platelets are shed from very large cells called megakaryocytes.[18] This process of progressive differentiation occurs within the bone marrow. After the cells are matured, they enter the circulation.[19] Every day, over 2.5 billion red blood cells and platelets, and 50–100 billion granulocytes are produced in this way.[20]

As well as creating cells, bone marrow is also one of the major sites where defective or aged red blood cells are destroyed.[20]

Metabolic

[edit]- Mineral storage – bones act as reserves of minerals important for the body, most notably calcium and phosphorus.[21][22][23]

Determined by the species, age, and the type of bone, bone cells make up to 15 percent of the bone. Growth factor storage—mineralized bone matrix stores important growth factors such as insulin-like growth factors, transforming growth factor, bone morphogenetic proteins and others.[24]

- Fat storage – marrow adipose tissue (MAT) acts as a storage reserve of fatty acids.[25]

- Acid-base balance – bone buffers the blood against excessive pH changes by absorbing or releasing alkaline salts.[26]

- Detoxification – bone tissues can also store heavy metals and other foreign elements, removing them from the blood and reducing their effects on other tissues. These can later be gradually released for excretion.[27]

- Endocrine organ – bone controls phosphate metabolism by releasing fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), which acts on kidneys to reduce phosphate reabsorption. Bone cells also release a hormone called osteocalcin, which contributes to the regulation of blood sugar (glucose) and fat deposition. Osteocalcin increases both the insulin secretion and sensitivity, in addition to boosting the number of insulin-producing cells and reducing stores of fat.[28]

- Calcium balance – the process of bone resorption by the osteoclasts releases stored calcium into the systemic circulation and is an important process in regulating calcium balance. As bone formation actively fixes circulating calcium in its mineral form, removing it from the bloodstream, resorption actively unfixes it thereby increasing circulating calcium levels. These processes occur in tandem at site-specific locations.[29]

Tissue

[edit]Bone is not uniformly solid, but consists of a flexible matrix (about 30%) and bound minerals (about 70%), which are intricately woven and continuously remodeled by a group of specialized bone cells. Their unique composition and design allows bones to be relatively hard and strong, while remaining lightweight. Bone matrix is 90 to 95% composed of elastic collagen fibers, also known as ossein,[30] and the remainder is ground substance.[31] The elasticity of collagen improves fracture resistance.[12] The matrix is hardened by the binding of inorganic mineral salt, calcium phosphate, in a chemical arrangement known as bone mineral, a form of calcium apatite.[32][33] It is the mineralization that gives bones rigidity.

Within any single bone, the tissue is woven into two main patterns: cortical and cancellous bone, each with distinct appearances and characteristics. Bone is actively constructed and remodeled throughout life by specialized bone cells known as osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

Cortex

[edit]

The hard outer layer of bones is composed of cortical bone, which is also called compact bone as it is much denser than cancellous bone. It forms the hard exterior (cortex) of bones. The cortical bone gives bone its smooth, white, and solid appearance, and accounts for 80% of the total bone mass of an adult human skeleton.[34] It facilitates bone's main functions—to support the whole body, to protect organs, to provide levers for movement, and to store and release chemical elements, mainly calcium. It consists of multiple microscopic columns, each called an osteon or Haversian system. Each column is multiple layers of osteoblasts and osteocytes around a central canal called the osteonic canal. Volkmann's canals at right angles connect the osteons together. The columns are metabolically active, and as bone is reabsorbed and created the nature and location of the cells within the osteon will change. Cortical bone is covered by a periosteum on its outer surface, and an endosteum on its inner surface. The endosteum is the boundary between the cortical bone and the cancellous bone.[35] The primary anatomical and functional unit of cortical bone is the osteon.

Trabeculae

[edit]

Cancellous bone or spongy bone,[36][35] also known as trabecular bone, is the internal tissue of the skeletal bone and is an open cell porous network that follows the material properties of biofoams.[37][38] Cancellous bone has a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio than cortical bone and it is less dense. This makes it weaker and more flexible. The greater surface area also makes it suitable for metabolic activities such as the exchange of calcium ions. Cancellous bone is typically found at the ends of long bones, near joints, and in the interior of vertebrae. Cancellous bone is highly vascular and often contains red bone marrow where hematopoiesis, the production of blood cells, occurs. The primary anatomical and functional unit of cancellous bone is the trabecula. The trabeculae are aligned towards the mechanical load distribution that a bone experiences within long bones such as the femur. As far as short bones are concerned, trabecular alignment has been studied in the vertebral pedicle.[39] Thin formations of osteoblasts covered in endosteum create an irregular network of spaces,[40] known as trabeculae. Within these spaces are bone marrow and hematopoietic stem cells that give rise to platelets, red blood cells and white blood cells.[40] Trabecular marrow is composed of a network of rod- and plate-like elements that make the overall organ lighter and allow room for blood vessels and marrow. Trabecular bone accounts for the remaining 20% of total bone mass but has nearly ten times the surface area of compact bone.[41]

The words cancellous and trabecular refer to the tiny lattice-shaped units (trabeculae) that form the tissue. It was first illustrated accurately in the engravings of Crisóstomo Martinez.[42]

Marrow

[edit]Bone marrow, also known as myeloid tissue in red bone marrow, can be found in almost any bone that holds cancellous tissue. In newborns, all such bones are filled exclusively with red marrow or hematopoietic marrow, but as the child ages the hematopoietic fraction decreases in quantity and the fatty/ yellow fraction called marrow adipose tissue (MAT) increases in quantity. In adults, red marrow is mostly found in the bone marrow of the femur, the ribs, the vertebrae and pelvic bones.[43]

Vascular supply

[edit]Bone receives about 10% of cardiac output.[44] Blood enters the endosteum, flows through the marrow, and exits through small vessels in the cortex.[44] In humans, blood oxygen tension in bone marrow is about 6.6%, compared to about 12% in arterial blood, and 5% in venous and capillary blood.[44]

Histology and physiology

[edit]

Bone is metabolically active tissue composed of several types of cells. These cells include osteoblasts, which are involved in the creation and mineralization of bone tissue, osteocytes, and osteoclasts, which are involved in the reabsorption of bone tissue. Osteoblasts and osteocytes are derived from osteoprogenitor cells, but osteoclasts are derived from the same cells that differentiate to form macrophages and monocytes.[45] Within the marrow of the bone there are also hematopoietic stem cells. These cells give rise to other cells, including white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets.[20]

Osteoblast

[edit]

Osteoblasts are mononucleate bone-forming cells. They are located on the surface of osteon seams and make a protein mixture known as osteoid, which mineralizes to become bone.[46] The osteoid seam is a narrow region of a newly formed organic matrix, not yet mineralized, located on the surface of a bone. Osteoid is primarily composed of Type I collagen. Osteoblasts also manufacture hormones, such as prostaglandins, to act on the bone itself. The osteoblast creates and repairs new bone by actually building around itself. First, the osteoblast puts up collagen fibers. These collagen fibers are used as a framework for the osteoblasts' work. The osteoblast then deposits calcium phosphate which is hardened by hydroxide and bicarbonate ions. The brand-new bone created by the osteoblast is called osteoid.[47] Once the osteoblast is finished working it is actually trapped inside the bone once it hardens. When the osteoblast becomes trapped, it becomes known as an osteocyte. Other osteoblasts remain on the top of the new bone and are used to protect the underlying bone, these become known as bone lining cells.[48]

Osteocyte

[edit]Osteocytes are cells of mesenchymal origin and originate from osteoblasts that have migrated into and become trapped and surrounded by a bone matrix that they themselves produced.[35] The spaces the cell body of osteocytes occupy within the mineralized collagen type I matrix are known as lacunae, while the osteocyte cell processes occupy channels called canaliculi. The many processes of osteocytes reach out to meet osteoblasts, osteoclasts, bone lining cells, and other osteocytes probably for the purposes of communication.[49] Osteocytes remain in contact with other osteocytes in the bone through gap junctions—coupled cell processes which pass through the canalicular channels.

Osteoclast

[edit]Osteoclasts are very large multinucleate cells that are responsible for the breakdown of bones by the process of bone resorption. New bone is then formed by the osteoblasts. Bone is constantly remodeled by the resorption of osteoclasts and created by osteoblasts.[45] Osteoclasts are large cells with multiple nuclei located on bone surfaces in what are called Howship's lacunae (or resorption pits). These lacunae are the result of surrounding bone tissue that has been reabsorbed.[50] Because the osteoclasts are derived from a monocyte stem-cell lineage, they are equipped with phagocytic-like mechanisms similar to circulating macrophages.[45] Osteoclasts mature and/or migrate to discrete bone surfaces. Upon arrival, active enzymes, such as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, are secreted against the mineral substrate.[citation needed] The reabsorption of bone by osteoclasts also plays a role in calcium homeostasis.[50]

Composition

[edit]Bones consist of living cells (osteoblasts and osteocytes) embedded in a mineralized organic matrix. The primary inorganic component of human bone is hydroxyapatite, the dominant bone mineral, having the nominal composition of Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2.[51] The organic components of this matrix consist mainly of type I collagen—"organic" referring to materials produced as a result of the human body—and inorganic components, which alongside the dominant hydroxyapatite phase, include other compounds of calcium and phosphate including salts. Approximately 30% of the acellular component of bone consists of organic matter, while roughly 70% by mass is attributed to the inorganic phase.[52] The collagen fibers give bone its tensile strength, and the interspersed crystals of hydroxyapatite give bone its compressive strength. These effects are synergistic.[52] The exact composition of the matrix may be subject to change over time due to nutrition and biomineralization, with the ratio of calcium to phosphate varying between 1.3 and 2.0 (per weight), and trace minerals such as magnesium, sodium, potassium and carbonate also be found.[52]

Type I collagen composes 90–95% of the organic matrix, with the remainder of the matrix being a homogenous liquid called ground substance consisting of proteoglycans such as hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate,[52] as well as non-collagenous proteins such as osteocalcin, osteopontin or bone sialoprotein. Collagen consists of strands of repeating units, which give bone tensile strength, and are arranged in an overlapping fashion that prevents shear stress. The function of ground substance is not fully known.[52] Two types of bone can be identified microscopically according to the arrangement of collagen: woven and lamellar.

- Woven bone (also known as fibrous bone), which is characterized by a haphazard organization of collagen fibers and is mechanically weak.[53]

- Lamellar bone, which has a regular parallel alignment of collagen into sheets ("lamellae") and is mechanically strong.[38][53]

Woven bone is produced when osteoblasts produce osteoid rapidly, which occurs initially in all fetal bones, but is later replaced by more resilient lamellar bone. In adults, woven bone is created after fractures or in Paget's disease. Woven bone is weaker, with a smaller number of randomly oriented collagen fibers, but forms quickly; it is for this appearance of the fibrous matrix that the bone is termed woven. It is soon replaced by lamellar bone, which is highly organized in concentric sheets with a much lower proportion of osteocytes to surrounding tissue. Lamellar bone, which makes its first appearance in humans in the fetus during the third trimester,[54] is stronger and filled with many collagen fibers parallel to other fibers in the same layer (these parallel columns are called osteons). In cross-section, the fibers run in opposite directions in alternating layers, much like in plywood, assisting in the bone's ability to resist torsion forces. After a fracture, woven bone forms initially and is gradually replaced by lamellar bone during a process known as "bony substitution". Compared to woven bone, lamellar bone formation takes place more slowly. The orderly deposition of collagen fibers restricts the formation of osteoid to about 1 to 2 μm per day. Lamellar bone also requires a relatively flat surface to lay the collagen fibers in parallel or concentric layers.[55]

Deposition

[edit]The extracellular matrix of bone is laid down by osteoblasts, which secrete both collagen and ground substance. These cells synthesise collagen alpha polypeptide chains and then secrete collagen molecules. The collagen molecules associate with their neighbors and crosslink via lysyl oxidase to form collagen fibrils. At this stage, they are not yet mineralized, and this zone of unmineralized collagen fibrils is called "osteoid". Around and inside collagen fibrils calcium and phosphate eventually precipitate within days to weeks becoming then fully mineralized bone with an overall carbonate substituted hydroxyapatite inorganic phase.[56][52]

In order to mineralise the bone, the osteoblasts secrete alkaline phosphatase, some of which is carried by vesicles. This cleaves the inhibitory pyrophosphate and simultaneously generates free phosphate ions for mineralization, acting as the foci for calcium and phosphate deposition. Vesicles may initiate some of the early mineralization events by rupturing and acting as a centre for crystals to grow on. Bone mineral may be formed from globular and plate structures, and via initially amorphous phases.[57][58]

Development

[edit]

The formation of bone is called ossification. During the fetal stage of development this occurs by two processes: intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification.[59] Intramembranous ossification involves the formation of bone from connective tissue whereas endochondral ossification involves the formation of bone from cartilage.

Intramembranous ossification mainly occurs during formation of the flat bones of the skull but also the mandible, maxilla, and clavicles; the bone is formed from connective tissue such as mesenchyme tissue rather than from cartilage. The process includes: the development of the ossification center, calcification, trabeculae formation and the development of the periosteum.[60]

Endochondral ossification occurs in long bones and most other bones in the body; it involves the development of bone from cartilage. This process includes the development of a cartilage model, its growth and development, development of the primary and secondary ossification centers, and the formation of articular cartilage and the epiphyseal plates.[61]

Endochondral ossification begins with points in the cartilage called "primary ossification centers". They mostly appear during fetal development, though a few short bones begin their primary ossification after birth. They are responsible for the formation of the diaphyses of long bones, short bones and certain parts of irregular bones. Secondary ossification occurs after birth and forms the epiphyses of long bones and the extremities of irregular and flat bones. The diaphysis and both epiphyses of a long bone are separated by a growing zone of cartilage (the epiphyseal plate). At skeletal maturity (18 to 25 years of age), all of the cartilage is replaced by bone, fusing the diaphysis and both epiphyses together (epiphyseal closure).[62] In the upper limbs, only the diaphyses of the long bones and scapula are ossified. The epiphyses, carpal bones, coracoid process, medial border of the scapula, and acromion are still cartilaginous.[63]

The following steps are followed in the conversion of cartilage to bone:

- Zone of reserve cartilage. This region, farthest from the marrow cavity, consists of typical hyaline cartilage that as yet shows no sign of transforming into bone.[64]

- Zone of cell proliferation. A little closer to the marrow cavity, chondrocytes multiply and arrange themselves into longitudinal columns of flattened lacunae.[64]

- Zone of cell hypertrophy. Next, the chondrocytes cease to divide and begin to hypertrophy (enlarge), much like they do in the primary ossification center of the fetus. The walls of the matrix between lacunae become very thin.[64]

- Zone of calcification. Minerals are deposited in the matrix between the columns of lacunae and calcify the cartilage. These are not the permanent mineral deposits of bone, but only a temporary support for the cartilage that would otherwise soon be weakened by the breakdown of the enlarged lacunae.[64]

- Zone of bone deposition. Within each column, the walls between the lacunae break down and the chondrocytes die. This converts each column into a longitudinal channel, which is immediately invaded by blood vessels and marrow from the marrow cavity. Osteoblasts line up along the walls of these channels and begin depositing concentric lamellae of matrix, while osteoclasts dissolve the temporarily calcified cartilage.[64]

Bone development in youth is extremely important in preventing future complications of the skeletal system. Regular exercise during childhood and adolescence can help improve bone architecture, making bones more resilient and less prone to fractures in adulthood. Physical activity, specifically resistance training, stimulates growth of bones by increasing both bone density and strength. Studies have shown a positive correlation between the adaptations of resistance training and bone density.[65] While nutritional and pharmacological approaches may also improve bone health, the strength and balance adaptations from resistance training are a substantial added benefit.[65] Weight-bearing exercise may assist in osteoblast (bone-forming cells) formation and help to increase bone mineral content. High-impact sports, which involve quick changes in direction, jumping, and running, are particularly effective with stimulating bone growth in the youth.[66] Sports such as soccer, basketball, and tennis have shown to have positive effects on bone mineral density as well as bone mineral content in teenagers.[66] Engaging in physical activity during childhood years, particularly in these high-impact osteogenic sports, can help to positively influence bone mineral density in adulthood.[67] Children and adolescents who participate in regular physical activity will place the groundwork for bone health later in life, reducing the risk of bone-related conditions such as osteoporosis.[67]

Remodeling

[edit]Bone is constantly being created and replaced in a process known as remodeling. This ongoing turnover of bone is a process of resorption followed by replacement of bone with little change in shape. This is accomplished through osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Cells are stimulated by a variety of signals, and together referred to as a remodeling unit. Approximately 10% of the skeletal mass of an adult is remodelled each year.[68] The purpose of remodeling is to regulate calcium homeostasis, repair microdamaged bones from everyday stress, and to shape the skeleton during growth.[69] Repeated stress, such as weight-bearing exercise or bone healing, results in the bone thickening at the points of maximum stress (Wolff's law). It has been hypothesized that this is a result of bone's piezoelectric properties, which cause bone to generate small electrical potentials under stress.[70]

The action of osteoblasts and osteoclasts are controlled by a number of chemical enzymes that either promote or inhibit the activity of the bone remodeling cells, controlling the rate at which bone is made, destroyed, or changed in shape. The cells also use paracrine signalling to control the activity of each other.[26][71] For example, the rate at which osteoclasts resorb bone is inhibited by calcitonin and osteoprotegerin. Calcitonin is produced by parafollicular cells in the thyroid gland, and can bind to receptors on osteoclasts to directly inhibit osteoclast activity. Osteoprotegerin is secreted by osteoblasts and is able to bind RANK-L, inhibiting osteoclast stimulation.[72]

Osteoblasts can also be stimulated to increase bone mass through increased secretion of osteoid and by inhibiting the ability of osteoclasts to break down osseous tissue.[citation needed] Increased secretion of osteoid is stimulated by the secretion of growth hormone by the pituitary, thyroid hormone and the sex hormones (estrogens and androgens). These hormones also promote increased secretion of osteoprotegerin.[72] Osteoblasts can also be induced to secrete a number of cytokines that promote reabsorption of bone by stimulating osteoclast activity and differentiation from progenitor cells. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and stimulation from osteocytes induce osteoblasts to increase secretion of RANK-ligand and interleukin 6, which cytokines then stimulate increased reabsorption of bone by osteoclasts. These same compounds also increase secretion of macrophage colony-stimulating factor by osteoblasts, which promotes the differentiation of progenitor cells into osteoclasts, and decrease secretion of osteoprotegerin.[citation needed]

Volume

[edit]Bone volume is determined by the rates of bone formation and bone resorption. Certain growth factors may work to locally alter bone formation by increasing osteoblast activity. Numerous bone-derived growth factors have been isolated and classified via bone cultures. These factors include insulin-like growth factors I and II, transforming growth factor-beta, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and bone morphogenetic proteins.[73] Evidence suggests that bone cells produce growth factors for extracellular storage in the bone matrix. The release of these growth factors from the bone matrix could cause the proliferation of osteoblast precursors. Essentially, bone growth factors may act as potential determinants of local bone formation.[73] Cancellous bone volume in postmenopausal osteoporosis may be determined by the relationship between the total bone forming surface and the percent of surface resorption.[74]

Clinical significance

[edit]A number of diseases can affect bone, including arthritis, fractures, infections, osteoporosis and tumors. Conditions relating to bone can be managed by a variety of doctors, including rheumatologists for joints, and orthopedic surgeons, who may conduct surgery to fix broken bones. Other doctors, such as rehabilitation specialists may be involved in recovery, radiologists in interpreting the findings on imaging, and pathologists in investigating the cause of the disease, and family doctors may play a role in preventing complications of bone disease such as osteoporosis.

When a doctor sees a patient, a history and exam will be taken. Bones are then often imaged, called radiography. This might include ultrasound X-ray, CT scan, MRI scan and other imaging such as a Bone scan, which may be used to investigate cancer.[75] Other tests such as a blood test for autoimmune markers may be taken, or a synovial fluid aspirate may be taken.[75]

Fractures

[edit]

In normal bone, fractures occur when there is significant force applied or repetitive trauma over a long time. Fractures can also occur when a bone is weakened, such as with osteoporosis, or when there is a structural problem, such as when the bone remodels excessively (such as Paget's disease) or is the site of the growth of cancer.[76] Common fractures include wrist fractures and hip fractures, associated with osteoporosis, vertebral fractures associated with high-energy trauma and cancer, and fractures of long-bones. Not all fractures are painful.[76] When serious, depending on the fractures type and location, complications may include flail chest, compartment syndromes or fat embolism. Compound fractures involve the bone's penetration through the skin. Some complex fractures can be treated by the use of bone grafting procedures that replace missing bone portions.

Fractures and their underlying causes can be investigated by X-rays, CT scans and MRIs.[76] Fractures are described by their location and shape, and several classification systems exist, depending on the location of the fracture. A common long bone fracture in children is a Salter–Harris fracture.[77] When fractures are managed, pain relief is often given, and the fractured area is often immobilised. This is to promote bone healing. In addition, surgical measures such as internal fixation may be used. Because of the immobilisation, people with fractures are often advised to undergo rehabilitation.[76]

Tumors

[edit]Tumor that can affect bone in several ways. Examples of benign bone tumors include osteoma, osteoid osteoma, osteochondroma, osteoblastoma, enchondroma, giant-cell tumor of bone, and aneurysmal bone cyst.[78]

Cancer

[edit]Cancer can arise in bone tissue, and bones are also a common site for other cancers to spread (metastasise) to.[79] Cancers that arise in bone are called "primary" cancers, although such cancers are rare.[79] Metastases within bone are "secondary" cancers, with the most common being breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid cancer, and kidney cancer.[79] Secondary cancers that affect bone can either destroy bone (called a "lytic" cancer) or create bone (a "sclerotic" cancer). Cancers of the bone marrow inside the bone can also affect bone tissue, examples including leukemia and multiple myeloma. Bone may also be affected by cancers in other parts of the body. Cancers in other parts of the body may release parathyroid hormone or parathyroid hormone-related peptide. This increases bone reabsorption, and can lead to bone fractures.

Bone tissue that is destroyed or altered as a result of cancers is distorted, weakened, and more prone to fracture. This may lead to compression of the spinal cord, destruction of the marrow resulting in bruising, bleeding and immunosuppression, and is one cause of bone pain. If the cancer is metastatic, then there might be other symptoms depending on the site of the original cancer. Some bone cancers can also be felt.

Cancers of the bone are managed according to their type, their stage, prognosis, and what symptoms they cause. Many primary cancers of bone are treated with radiotherapy. Cancers of bone marrow may be treated with chemotherapy, and other forms of targeted therapy such as immunotherapy may be used.[80] Palliative care, which focuses on maximising a person's quality of life, may play a role in management, particularly if the likelihood of survival within five years is poor.

Diabetes

[edit]Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks the insulin-producing pancreas cells causing the body to not make enough insulin.[81] In contrast type 2 diabetes in which the body creates enough Insulin, but becomes resistant to it over time.[81]

Children makeup approximately 85% of Type 1 Diabetes cases and in America there was an average 22% rise in cases[82] over the first 24 months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. With the increase of developing some form of diabetes across all ranges continually growing the health impacts on bone development and bone health in these populations are still being researched. Most evidence suggests that diabetes, either Type 1 and Type 2, inhibits osteoblastic activity[83] and causes both lower BMD and BMC in both adults and children. The weakening of these developmental aspects is thought to lead to an increased risk of developing many diseases such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, osteopenia and fractures.[84] Development of any of these diseases is thought to be correlated with a decrease in ability to perform in athletic environments and activities of daily living.

Focusing on therapies that target molecules like osteocalcin or AGEs could provide new ways to improve bone health and help manage the complications of diabetes more effectively.[85]

Other painful conditions

[edit]- Osteomyelitis is inflammation of the bone or bone marrow due to bacterial infection.[86]

- Osteomalacia is a painful softening of adult bone caused by severe vitamin D deficiency.[87]

- Osteogenesis imperfecta[88]

- Osteochondritis dissecans[89]

- Ankylosing spondylitis[90]

- Skeletal fluorosis is a bone disease caused by an excessive accumulation of fluoride in the bones. In advanced cases, skeletal fluorosis damages bones and joints and is painful.[91]

Osteoporosis

[edit]

Osteoporosis is a disease of bone where there is reduced bone mineral density, increasing the likelihood of fractures.[92] Osteoporosis is defined in women by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density of 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass, relative to the age and sex-matched average. This density is measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), with the term "established osteoporosis" including the presence of a fragility fracture.[93] Osteoporosis is most common in women after menopause, when it is called "postmenopausal osteoporosis", but may develop in men and premenopausal women in the presence of particular hormonal disorders and other chronic diseases or as a result of smoking and medications, specifically glucocorticoids.[92] Osteoporosis usually has no symptoms until a fracture occurs.[92] For this reason, DEXA scans are often done in people with one or more risk factors, who have developed osteoporosis and are at risk of fracture.[92]

One of the most important risk factors for osteoporosis is advanced age. Accumulation of oxidative DNA damage in osteoblastic and osteoclastic cells appears to be a key factor in age-related osteoporosis.[94]

Osteoporosis treatment includes advice to stop smoking, decrease alcohol consumption, exercise regularly, and have a healthy diet. Calcium and trace mineral supplements may also be advised, as may Vitamin D. When medication is used, it may include bisphosphonates, Strontium ranelate, and hormone replacement therapy.[95]

Bone health

[edit]Without strong healthy bones, humans are more at risk for different chronic diseases and fractures, with day-to-day function being more difficult with poor bone health. It is estimated that diet and exercise during childhood can impact peak bone mass as an adult nearly 20–40%.[96] One study done on children with developmental coordination disorder found an increase in bone mass up to 4% and 5% in the cortical areas of the tibia alone from a 13-week training period.[97] Peak bone mass occurs between the second and third decade of most people's lives.[98] Studies have shown that increasing calcium stores in childhood via food intake result in significant improvements in bone-mass density and overall health, even into adulthood.[99][100][101]

Osteology

[edit]

The study of bones and teeth is referred to as osteology. It is frequently used in anthropology, archeology and forensic science for a variety of tasks. This can include determining the nutritional, health, age or injury status of the individual the bones were taken from. Preparing fleshed bones for these types of studies can involve the process of maceration.[citation needed]

Typically anthropologists and archeologists study bone tools made by Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis. Bones can serve a number of uses such as projectile points or artistic pigments, and can also be made from external bones such as antlers.[citation needed]

Other animals

[edit]

Bird skeletons are very lightweight. Their bones are smaller and thinner than those of mammals, to aid flight. Among mammals, bats come closest to birds in terms of bone density, suggesting that small dense bones are a flight adaptation. Many bird bones have little marrow due to them being hollow.[102] A bird's beak is primarily made of bone as projections of the mandibles which are covered in keratin.

Some bones, primarily formed separately in subcutaneous tissues, include headgears (such as bony core of horns, antlers, ossicones), osteoderm, and os penis/os clitoris.[103] A deer's antlers are composed of bone which is an unusual example of bone being outside the skin of the animal once the velvet is shed.[104]

The extinct predatory fish Dunkleosteus had sharp edges of hard exposed bone along its jaws.[105][106]

The proportion of cortical bone that is 80% in the human skeleton may be much lower in other animals, especially in marine mammals and marine turtles, or in various Mesozoic marine reptiles, such as ichthyosaurs,[107] among others.[108] This proportion can vary quickly in evolution; it often increases in early stages of returns to an aquatic lifestyle, as seen in early whales and pinnipeds, among others. It subsequently decreases in pelagic taxa, which typically acquire spongy bone, but aquatic taxa that live in shallow water can retain very thick, pachyostotic,[109] osteosclerotic, or pachyosteosclerotic[110] bones, especially if they move slowly, like sea cows. In some cases, even marine taxa that had acquired spongy bone can revert to thicker, compact bones if they become adapted to live in shallow water, or in hypersaline (denser) water.[111][112][113]

Many animals, particularly herbivores, practice osteophagy—the eating of bones. This is presumably carried out in order to replenish lacking phosphate.

Many bone diseases that affect humans also affect other vertebrates—an example of one disorder is skeletal fluorosis.

Society and culture

[edit]

Bones from slaughtered animals have a number of uses:

- In prehistoric times, they have been used for making bone tools.[114] They have further been used in bone carving, already important in prehistoric art, and also in modern time as crafting materials for buttons, beads, handles, bobbins, calculation aids, head nuts, dice, poker chips, pick-up sticks, arrows, scrimshaw, and ornaments.

- Bone glue can be made by prolonged boiling of ground or cracked bones, followed by filtering and evaporation to thicken the resulting fluid. Historically once important, bone glue and other animal glues today have only a few specialized uses, such as in antiques restoration. Essentially the same process, with further refinement, thickening and drying, is used to make gelatin.

- Broth is made by simmering several ingredients for a long time, traditionally including bones.

- Bone char, a porous, black, granular material primarily used for filtration and also as a black pigment, is produced by charring mammal bones.

- Oracle bone script was a writing system used in ancient China based on inscriptions in bones. Its name originates from oracle bones, which were mainly ox clavicle. The Ancient Chinese (mainly in the Shang dynasty), would write their questions on the oracle bone, and burn the bone, and where the bone cracked would be the answer for the questions.

- The wishbones of fowl have been used for divination, and are still customarily used in a tradition to determine which one of two people pulling on either prong of the bone may make a wish.

To point the bone at someone is considered bad luck in some cultures, such as Australian aborigines, such as by the Kurdaitcha.

Various cultures throughout history have adopted the custom of shaping an infant's head by the practice of artificial cranial deformation. A widely practised custom in China was that of foot binding to limit the normal growth of the foot.

Additional images

[edit]-

Cells in bone marrow

-

Scanning electron microscope of bone at 100× magnification

-

Structure detail of an animal bone

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lee C (January 2001). The Bone Organ System: Form and Function. Academic Press. pp. 3–20. doi:10.1016/B978-012470862-4/50002-7. ISBN 978-0-12-470862-4. Retrieved 30 January 2022 – via Science Direct.

- ^ de Buffrénil V, de Ricqlès AJ, Zylberberg L, Padian K, Laurin M, Quilhac A (2021). Vertebrate skeletal histology and paleohistology (First ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. xii + 825. ISBN 978-1-351-18957-6.

- ^ Langley, Natalie, Tersigni-Terrant, Maria-Teresa, eds. (2017). Forensic Anthropology: A Comprehensive Approach (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-315-30003-0.

- ^ Steele DG, Bramblett CA (1988). The Anatomy and Biology of the Human Skeleton. Texas A&M University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-89096-300-5.

- ^ Mammal anatomy: an illustrated guide. New York: Marshall Cavendish. 2010. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7614-7882-9.

- ^ "Types of bone". mananatomy.com. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "DoITPoMS – TLP Library Structure of bone and implant materials – Structure and composition of bone". Dissemination of IT for the Promotion of Materials Science (DoITPoMS). Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge.

- ^

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts JG, Desaix P, Johnson E, Johnson JE, Korol O, Kruse D, et al. (8 June 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 6.2 Bone classification. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts JG, Desaix P, Johnson E, Johnson JE, Korol O, Kruse D, et al. (8 June 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 6.2 Bone classification. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ^ Clarke B (2008), "Normal Bone Anatomy and Physiology", Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3 (Suppl 3): S131 – S139, doi:10.2215/CJN.04151206, PMC 3152283, PMID 18988698

- ^ Jerez A, Mangione S, Abdala V (2010), "Occurrence and distribution of sesamoid bones in squamates: a comparative approach", Acta Zoologica, 91 (3): 295–305, doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2009.00408.x, hdl:11336/74304

- ^ Pratt R. "Bone as an Organ". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b Schmidt-Nielsen K (1984). Scaling: Why Is Animal Size So Important?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-31987-4.

- ^ Vincent K. "Topic 3: Structure and Mechanical Properties of Bone". BENG 112A Biomechanics, Winter Quarter, 2013. Department of Bioengineering, University of California. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Turner CH, Wang T, Burr DB (December 2001). "Shear strength and fatigue properties of human cortical bone determined from pure shear tests". Calcified Tissue International. 69 (6): 373–378. doi:10.1007/s00223-001-1006-1. PMID 11800235. S2CID 30348345.

- ^ Fernández KS, de Alarcón PA (December 2013). "Development of the hematopoietic system and disorders of hematopoiesis that present during infancy and early childhood". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 60 (6): 1273–1289. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2013.08.002. PMID 24237971.

- ^ Young 2006, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Young 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Young 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Young 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Young 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Doyle ME, Jan de Beur SM (December 2008). "The skeleton: endocrine regulator of phosphate homeostasis". Current Osteoporosis Reports. 6 (4): 134–141. doi:10.1007/s11914-008-0024-6. PMID 19032923. S2CID 23298442.

- ^ "Bone Health In Depth". Linus Pauling Institute. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Walker K. "Bone". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Hauschka PV, Chen TL, Mavrakos AE (1988). "Polypeptide Growth Factors in Bone Matrix". Ciba Foundation Symposium 136 - Cell and Molecular Biology of Vertebrate Hard Tissues. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 136. pp. 207–225. doi:10.1002/9780470513637.ch13. ISBN 978-0-470-51363-7. PMID 3068010.

- ^ Styner M, Pagnotti GM, McGrath C, Wu X, Sen B, Uzer G, et al. (August 2017). "Exercise Decreases Marrow Adipose Tissue Through β-Oxidation in Obese Running Mice". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 32 (8): 1692–1702. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3159. PMC 5550355. PMID 28436105.

- ^ a b Fogelman I, Gnanasegaran G, van der Wall H (2013). Radionuclide and Hybrid Bone Imaging. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-02400-9.

- ^ Lerro E (2007). "Bone". flipper.diff.org.

- ^ Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, et al. (August 2007). "Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton". Cell. 130 (3): 456–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. PMC 2013746. PMID 17693256.

- ^ Wilkin D, Gray-Wilson N (8 February 2024). "Bones". CK-12 Foundation.

- ^ "Ossein". The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Hall J (2011). Textbook of Medical Physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 957–960. ISBN 978-08089-2400-5.

- ^ Wopenka B, Pasteris JD (2005). "A mineralogical perspective on the apatite in bone". Materials Science and Engineering: C. 25 (2): 131–143. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2005.01.008.

- ^ Wang B, Zhang Z, Pan H (February 2023). "Bone Apatite Nanocrystal: Crystalline Structure, Chemical Composition, and Architecture". Biomimetics. 8 (1): 90. doi:10.3390/biomimetics8010090. PMC 10046636. PMID 36975320.

- ^ "Structure of Bone". flexbooks.ck12.org. CK12-Foundation. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Young 2006, p. 192.

- ^ "Structure of Bone Tissue". SEER Training. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) U.S. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Meyers MA, Chen PY, Lin AY, Seki Y (January 2008). "Biological materials: Structure and mechanical properties". Progress in Materials Science. 53 (1): 1–206. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2007.05.002. ISSN 0079-6425.

- ^ a b Buss DJ, Kröger R, McKee MD, Reznikov N (2022). "Hierarchical organization of bone in three dimensions: A twist of twists". Journal of Structural Biology. 6 100057. doi:10.1016/j.yjsbx.2021.100057. PMC 8762463. PMID 35072054.

- ^ Gdyczynski CM, Manbachi A, Hashemi S, Lashkari B, Cobbold RS (December 2014). "On estimating the directionality distribution in pedicle trabecular bone from micro-CT images". Physiological Measurement. 35 (12): 2415–2428. Bibcode:2014PhyM...35.2415G. doi:10.1088/0967-3334/35/12/2415. PMID 25391037. S2CID 206078730.

- ^ a b Young 2006, p. 195.

- ^ Hall SJ (2007). Basic Biomechanics with OLC (5th ed.). Burr Ridge: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-07-126041-1.

- ^ Gomez S (February 2002). "Crisóstomo Martinez, 1638-1694: the discoverer of trabecular bone". Endocrine. 17 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1385/ENDO:17:1:03. PMID 12014701. S2CID 46340228.

- ^ Barnes-Svarney PL, Svarney TE (2016). The Handy Anatomy Answer Book: Includes Physiology. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-57859-542-6.

- ^ a b c Marenzana M, Arnett TR (September 2013). "The Key Role of the Blood Supply to Bone". Bone Research. 1 (3): 203–215. doi:10.4248/BR201303001. PMC 4472103. PMID 26273504.

- ^ a b c Young 2006, p. 189.

- ^ Young 2006, pp. 189–190.

- ^ "The O' Cells". Bone Cells. The University of Washington. 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011.

- ^ Wein MN (28 April 2017). "Bone Lining Cells: Normal Physiology and Role in Response to Anabolic Osteoporosis Treatments". Current Molecular Biology Reports. 3 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1007/s40610-017-0062-x. S2CID 36473110.

- ^ Sims NA, Vrahnas C (November 2014). "Regulation of cortical and trabecular bone mass by communication between osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 561: 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.015. PMID 24875146.

- ^ a b Young 2006, p. 190.

- ^ Enhancement of Hydroxyapatite Dissolution Journal of Materials Science & Technology,38, 148-158

- ^ a b c d e f Hall 2005, p. 981.

- ^ a b Currey, John D. (2002). "The Structure of Bone Tissue" Archived 25 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 12–14 in Bones: Structure and Mechanics. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. ISBN 978-1-4008-4950-5

- ^ Salentijn, L. Biology of Mineralized Tissues: Cartilage and Bone, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine post-graduate dental lecture series, 2007

- ^ Royce PM, Steinmann B (14 April 2003). Connective Tissue and Its Heritable Disorders: Molecular, Genetic, and Medical Aspects. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-46117-3.

- ^ Buss DJ, Reznikov N, McKee MD (November 2020). "Crossfibrillar mineral tessellation in normal and Hyp mouse bone as revealed by 3D FIB-SEM microscopy". Journal of Structural Biology. 212 (2) 107603. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107603. PMID 32805412. S2CID 221164596.

- ^ Bertazzo S, Bertran CA (2006). "Morphological and dimensional characteristics of bone mineral crystals". Key Engineering Materials. 309–311: 3–6. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.309-311.3. S2CID 136883011.

- ^ Bertazzo S, Bertran C, Camilli J (2006). "Morphological Characterization of Femur and Parietal Bone Mineral of Rats at Different Ages". Key Engineering Materials. 309–311: 11–14. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.309-311.11. S2CID 135813389.

- ^ Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, et al. (25 April 2013). "6.4 Bone Formation and Development". Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Bone Growth and Development". Biology for Majors II. lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Tortora GJ, Derrickson BH (2018). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-44445-9.

- ^ "6.4B: Postnatal Bone Growth". Medicine LibreTexts. 19 July 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Agur A (2009). Grant's Atlas of Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-7817-7055-2.

- ^ a b c d e Saladin K (2012). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- ^ a b Layne JE, Nelson ME (January 1999). "The effects of progressive resistance training on bone density: a review". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 31 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1097/00005768-199901000-00006. PMID 9927006.

- ^ a b López-García R, Cruz-Castruita R, Morales-Corral P, Banda-Sauceda N, Lagunés-Carrasco J (16 December 2019). "Evaluación del mineral óseo con la dexa en futbolistas juveniles". Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte. 19 (76): 617–626. doi:10.15366/rimcafd2019.76.004 (inactive 4 September 2025). hdl:10486/689625. ISSN 1577-0354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2025 (link) - ^ a b Van Langendonck L, Lefevre J, Claessens AL, Thomis M, Philippaerts R, Delvaux K, et al. (September 2003). "Influence of participation in high-impact sports during adolescence and adulthood on bone mineral density in middle-aged men: a 27-year follow-up study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 158 (6): 525–533. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg170. PMID 12965878.

- ^ Manolagas SC (April 2000). "Birth and death of bone cells: basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis". Endocrine Reviews. 21 (2): 115–137. doi:10.1210/edrv.21.2.0395. PMID 10782361.

- ^ Hadjidakis DJ, Androulakis II (December 2006). "Bone remodeling". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1092 (1): 385–396. Bibcode:2006NYASA1092..385H. doi:10.1196/annals.1365.035. PMID 17308163. S2CID 39878618.

- ^ Woodburne RT, ed. (1999). Anatomy, physiology, and metabolic disorders (5th ed.). Summit, N.J.: Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp. pp. 187–189. ISBN 978-0-914168-88-1.

- ^ "Introduction to cell signaling (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ a b Boulpaep EL, Boron WF (2005). Medical physiology: a cellular and molecular approach. Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 1089–1091. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- ^ a b Mohan S, Baylink DJ (February 1991). "Bone growth factors". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 263 (263): 30–48. doi:10.1097/00003086-199102000-00004. PMID 1993386.

- ^ Nordin BE, Aaron J, Speed R, Crilly RG (August 1981). "Bone formation and resorption as the determinants of trabecular bone volume in postmenopausal osteoporosis". Lancet. 2 (8241): 277–279. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)90526-2. PMID 6114324. S2CID 29646037.

- ^ a b Davidson 2010, pp. 1059–1062.

- ^ a b c d Davidson 2010, p. 1068.

- ^ Salter RB, Harris WR (1963). "Injuries Involving the Epiphyseal Plate". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 45 (3): 587–622. doi:10.2106/00004623-196345030-00019. S2CID 73292249. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Benign Bone Tumours". Cleveland Clinic. 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Davidson 2010, p. 1125.

- ^ Davidson 2010, p. 1032.

- ^ a b Ndisang JF, Vannacci A, Rastogi S (2017). "Insulin Resistance, Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes, and Related Complications 2017". Journal of Diabetes Research. 2017 1478294. doi:10.1155/2017/1478294. PMC 5723935. PMID 29279853.

- ^ Kamrath C, Holl RW, Rosenbauer J (June 2023). "Elucidating the Underlying Mechanisms of the Marked Increase in Childhood Type 1 Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic-The Diabetes Pandemic". JAMA Network Open. 6 (6): e2321231. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21231. PMID 37389881.

- ^ Loxton P, Narayan K, Munns CF, Craig ME (August 2021). "Bone Mineral Density and Type 1 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis". Diabetes Care. 44 (8): 1898–1905. doi:10.2337/dc20-3128. PMC 8385468. PMID 34285100.

- ^ de Araújo IM, Moreira ML, de Paula FJ (November 2022). "Diabetes and bone". Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 66 (5): 633–641. doi:10.20945/2359-3997000000552. PMC 10118819. PMID 36382752.

- ^ Booth SL, Centi A, Smith SR, Gundberg C (January 2013). "The role of osteocalcin in human glucose metabolism: marker or mediator?". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 9 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2012.201. PMC 4441272. PMID 23147574.

- ^ "Osteomyelitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Osteomalacia and Rickets". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Osteogenesis Imperfecta". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Osteochondritis Dissecans". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Ankylosing Spondylitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Whitford GM (June 1994). "Intake and metabolism of fluoride". Advances in Dental Research. 8 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1177/08959374940080011001. PMID 7993560. S2CID 21763028.

- ^ a b c d Davidson 2010, pp. 1116–1121.

- ^ WHO (1994). "Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group". World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 843: 1–129. PMID 7941614.

- ^ Chen Q, Liu K, Robinson AR, et al. DNA damage drives accelerated bone aging via an NF-κB-dependent mechanism. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(5):1214-1228. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1851

- ^ Davidson 2010, pp. 1116–1121

- ^ Faienza MF, Urbano F, Chiarito M, Lassandro G, Giordano P (2023). "Musculoskeletal health in children and adolescents". Frontiers in Pediatrics. 11 1226524. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1226524. PMC 10754974. PMID 38161439.

- ^ Tan JL, Siafarikas A, Rantalainen T, Hart NH, McIntyre F, Hands B, et al. (December 2020). "Impact of a multimodal exercise program on tibial bone health in adolescents with Development Coordination Disorder: an examination of feasibility and potential efficacy". Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 20 (4): 445–471. PMC 7716678. PMID 33265073.

- ^ Baronio F, Baptista F (2022). "Editorial: Bone health and development in children and adolescents". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13 1101403. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.1101403. PMC 9791941. PMID 36578952.

- ^ Pan K, Zhang C, Yao X, Zhu Z (January 2020). "Association between dietary calcium intake and BMD in children and adolescents". Endocrine Connections. 9 (3): 194–200. doi:10.1530/EC-19-0534. PMC 7040863. PMID 31990673.

- ^ Closa-Monasterolo R, Zaragoza-Jordana M, Ferré N, Luque V, Grote V, Koletzko B, et al. (June 2018). "Adequate calcium intake during long periods improves bone mineral density in healthy children. Data from the Childhood Obesity Project". Clinical Nutrition. 37 (3): 890–896. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.03.011. PMID 28351509.

- ^ Gordon RJ, Misra M, Mitchell DM (2000). "Osteoporosis and Bone Fragility in Children". In Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A (eds.). Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. PMID 37490575. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Dumont ER (July 2010). "Bone density and the lightweight skeletons of birds". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 277 (1691): 2193–2198. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0117. PMC 2880151. PMID 20236981.

- ^ Nasoori A (August 2020). "Formation, structure, and function of extra-skeletal bones in mammals". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 95 (4): 986–1019. doi:10.1111/brv.12597. PMID 32338826. S2CID 216556342.

- ^ Rolf HJ, Enderle A (May 1999). "Hard fallow deer antler: a living bone till antler casting?". The Anatomical Record. 255 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990501)255:1<69::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-R. PMID 10321994.

- ^ "Dunkleosteus". American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ "My, What a Big Mouth You Have | Cleveland Museum of Natural History".

- ^ de Buffrénil V, Mazin JM (1990). "Bone histology of the ichthyosaurs: comparative data and functional interpretation". Paleobiology. 16 (4): 435–447. Bibcode:1990Pbio...16..435D. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010174. JSTOR 2400968. S2CID 88171648.

- ^ Laurin M, Canoville A, Germain D (2011). "Bone microanatomy and lifestyle: a descriptive approach". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 10 (5–6): 381–402. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.02.003.

- ^ Houssaye A, De Buffrenil V, Rage JC, Bardet N (12 September 2008). "An analysis of vertebral 'pachyostosis' in Carentonosaurus mineaui (Mosasauroidea, Squamata) from the Cenomanian (early Late Cretaceous) of France, with comments on its phylogenetic and functional significance". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3): 685–691. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[685:AAOVPI]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 129670238.

- ^ de Buffrénil V, Canoville A, D'Anastasio R, Domning DP (June 2010). "Evolution of Sirenian Pachyosteosclerosis, a Model-case for the Study of Bone Structure in Aquatic Tetrapods". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 17 (2): 101–120. doi:10.1007/s10914-010-9130-1. S2CID 39169019.

- ^ Dewaele L, Lambert O, Laurin M, De Kock T, Louwye S, de Buffrénil V (December 2019). "Generalized Osteosclerotic Condition in the Skeleton of Nanophoca vitulinoides, a Dwarf Seal from the Miocene of Belgium" (PDF). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 26 (4): 517–543. doi:10.1007/s10914-018-9438-9. S2CID 20885865.

- ^ Dewaele L, Gol'din P, Marx FG, Lambert O, Laurin M, Obadă T, et al. (January 2022). "Hypersalinity drives convergent bone mass increases in Miocene marine mammals from the Paratethys". Current Biology. 32 (1): 248–255.e2. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E.248D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.065. PMID 34813730. S2CID 244485732.

- ^ Houssaye A (January 2022). "Evolution: Back to heavy bones in salty seas" (PDF). Current Biology. 32 (1): R42 – R44. Bibcode:2022CBio...32..R42H. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.11.049. PMID 35015995. S2CID 245879886. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2022.

- ^ Laszlovszky J, Szabo P (January 2003). People and Nature in Historical Perspective. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-86-2.

Sources

[edit]- Davidson S (2010). Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH (eds.). Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine. Illustrated by Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- Hall AC, Guyton JE (2005). Textbook of Medical Physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- Young B, Lowe JS, Stevens A, Heath JW (2006). Wheater's Functional Histology: a text and colour atlas (5th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-068-508.

Further reading

[edit]- Derrickson BH, Tortora GJ (2005). Principles of anatomy and physiology. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-68934-8.

- Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, et al. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147692-8.

- Hoehn K, Marieb EN (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-5909-1.

- Kini U, Nandeesh BN (3 January 2013). "Ch 2: Physiology of Bone Formation, Remodeling, and Metabolism" (PDF). In Fogelman I, Gnanasegaran G, van der Wall H (eds.). Radionuclide and hybrid bone imaging. Berlin: Springer. pp. 29–57. ISBN 978-3-642-02399-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

External links

[edit]Structure and Composition

Macroscopic Structure

Bone tissue at the macroscopic level is organized into distinct layers and compartments that provide structural integrity, support metabolic functions, and facilitate nutrient exchange. Compact bone, also known as cortical bone, forms the dense outer layer of most bones and constitutes approximately 80% of the total skeletal mass in adults.[3] This layer offers primary mechanical strength and protection against external forces, appearing solid and smooth to the naked eye.[4] In contrast, cancellous bone, or trabecular bone, comprises the porous inner network within bones, characterized by a lattice of interconnected struts and plates that create a spongy architecture.[5] This structure is optimized for metabolic exchange due to its high surface area-to-volume ratio, while remaining lightweight to reduce overall skeletal weight.[4] The interior of bones contains marrow cavities that house different types of bone marrow depending on location and age. Red marrow, which is actively involved in hematopoiesis, is primarily found in the cavities of flat bones such as the pelvis and sternum, as well as in the epiphyses of long bones.[6] Yellow marrow, consisting mainly of adipose tissue for fat storage, occupies the medullary cavities of the diaphyses in long bones, particularly in adults where it replaces much of the red marrow over time.[7] These cavities are lined by a thin membrane that separates the marrow from the surrounding bone tissue. Vascular supply to bone is essential for its nourishment and maintenance, entering through specific anatomical openings. Nutrient arteries, the primary blood supply for the inner bone, penetrate the cortical layer via nutrient foramina—small openings typically located on the diaphysis of long bones—and branch into the medullary cavity to irrigate cancellous bone and marrow.[1] Periosteal vessels, arising from the outer surface, provide additional blood flow to the compact bone layer through a network of capillaries and anastomoses.[8] Venous drainage parallels this arterial system, exiting via similar foramina to return deoxygenated blood to the systemic circulation.[9] The outer and inner surfaces of bone are covered by specialized connective tissue layers that contribute to its overall organization. The periosteum is a dense, fibrous membrane enveloping the external surface of bones, excluding areas of articulation, and serves as the site for attachment of tendons, ligaments, and muscles while housing blood vessels and nerves.[8] Internally, the endosteum lines the marrow cavities, trabecular surfaces, and vascular canals within compact bone, forming a thin layer that interfaces with the bone matrix.[10]Microscopic Structure

Bone tissue exhibits distinct microscopic architectures that vary between cortical and trabecular regions, enabling specialized mechanical and metabolic functions. Cortical bone, also known as compact bone, consists of densely packed cylindrical units called osteons or Haversian systems, each featuring a central Haversian canal that houses blood vessels and nerves running parallel to the bone's long axis.[5] These canals are surrounded by concentric lamellae, which are layered sheets of mineralized matrix approximately 3-7 micrometers thick, providing structural integrity through organized deposition.[11] Between osteons, interstitial lamellae fill the spaces, formed from remnants of older osteons and contributing to the overall solidity of the tissue.[5] In contrast, trabecular bone, or spongy bone, displays a porous, lattice-like structure composed of interconnected trabeculae that form rods and plates, creating an open network of irregular cavities filled with bone marrow.[12] Unlike cortical bone, trabecular bone lacks organized osteons; instead, its trabeculae align along principal stress lines to optimize strength while minimizing mass, with a porosity often exceeding 50-90%.[5] Nutrient diffusion occurs through canaliculi connecting to adjacent marrow spaces and vascular elements, supporting the metabolic demands of this highly vascularized tissue.[12] The bone matrix, which constitutes about 90% of bone tissue by volume, is organized into lamellae where type I collagen fibers are arranged in parallel bundles, conferring tensile strength and flexibility to withstand mechanical loads.[13] Hydroxyapatite mineral crystals, primarily plate-like and 20-100 nanometers in length, align along the collagen fibrils within these lamellae, enhancing compressive resistance through a composite structure that mimics fiber-reinforced materials.[14] The ground substance interspersed among these fibers includes proteoglycans and glycoproteins, which bind water to maintain hydration, facilitate nutrient diffusion, and regulate matrix assembly.[15] Bone types differ microscopically in maturity and organization: woven bone, an immature form, features randomly oriented collagen fibers in a disorganized, basket-weave pattern, resulting in lower mechanical strength and higher remodeling rates.[16] Lamellar bone, the mature variant predominant in adults, exhibits highly ordered, layered collagen arrangements in concentric or parallel patterns, providing superior durability and resistance to fracture.[17] Osteocytes reside within lacunae embedded in the matrix, connected via canaliculi to vascular canals for nutrient exchange.[5]Cellular Components

Bone tissue is maintained by a dynamic population of specialized cells that orchestrate its formation, resorption, and homeostasis. The primary cellular components include osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts, bone-lining cells, and progenitor stem cells, each derived from distinct lineages and contributing uniquely to bone integrity. These cells interact within the bone microenvironment to ensure structural support and metabolic balance.[18] Osteoblasts are the bone-forming cells responsible for synthesizing and mineralizing the organic bone matrix. Derived from mesenchymal stem cells, they originate from osteoprogenitor precursors and differentiate under the influence of factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), RUNX2, and Osterix.[18][19] These mononuclear cells feature prominent Golgi apparatus and rough endoplasmic reticulum, enabling robust protein synthesis. Osteoblasts secrete osteoid, an unmineralized matrix primarily composed of type I collagen (about 90%) along with non-collagenous proteins, which they subsequently mineralize by depositing hydroxyapatite crystals via matrix vesicles containing alkaline phosphatase.[18][19] Upon completion of matrix deposition, osteoblasts may undergo apoptosis, flatten into bone-lining cells, or become embedded in the matrix as osteocytes.[18] Osteocytes represent the most abundant cell type in mature bone, comprising over 90-95% of all bone cells, and serve as mature, terminally differentiated osteoblasts entrapped within the mineralized matrix. They reside in lacunae and extend dendritic processes through a network of canaliculi, forming gap junctions that facilitate intercellular communication, nutrient diffusion, and mechanotransduction.[19][20] Osteocytes act as mechanosensors, detecting mechanical loading and regulating mineral homeostasis by secreting factors like fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) and sclerostin to modulate bone remodeling and phosphate levels.[18] With a lifespan of up to 25 years in humans, osteocytes are among the longest-lived cells in the body, enabling sustained oversight of bone tissue integrity.[21][20] Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells specialized for bone resorption, essential for calcium mobilization and skeletal remodeling. They derive from the monocyte-macrophage lineage of hematopoietic stem cells, where precursor monocytes fuse to form these large cells containing 5-20 nuclei.[18][19] During resorption, osteoclasts attach to the bone surface via a sealing zone, forming a ruffled border that creates an isolated resorption compartment. They acidify this space using vacuolar H+-ATPase proton pumps to dissolve hydroxyapatite and secrete lysosomal enzymes, notably cathepsin K, to degrade the organic matrix.[18][19] Degraded products are transcytosed across the cell and released at the functional secretory domain, preventing intracellular accumulation.[18] Bone-lining cells are flattened, quiescent osteoblasts that cover inactive bone surfaces, comprising a thin layer that modulates ion exchange between bone and extracellular fluid without active matrix production. Derived from osteoblasts that have ceased formation activity, they prevent direct contact between osteoclasts and the mineralized matrix during periods of low remodeling.[18][19] These cells express receptors for hormones and growth factors, enabling rapid activation into osteoblasts when bone formation is required.[19] Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) serve as multipotent progenitors for the osteoblast lineage within the bone marrow stroma and other connective tissues. These self-renewing cells differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, and other mesenchymal derivatives under specific signaling cues like BMPs and Wnt pathways.[18][19] In bone, MSCs commit to the osteoblastic pathway via osteoprogenitors, providing a renewable source for ongoing tissue maintenance and repair.[18]Chemical Composition

Bone tissue comprises an organic matrix, an inorganic mineral phase, and water, which together determine its structural integrity and biomechanical performance. By dry weight, the organic components constitute approximately 30-35% of bone mass, providing flexibility and resilience, while the inorganic phase accounts for 65-70%, imparting rigidity and hardness.[22][23] Water makes up 10-20% of the total bone volume, facilitating molecular diffusion, nutrient transport, and the plastic deformation necessary for absorbing mechanical stress without fracture.[23] The organic matrix is dominated by type I collagen, which forms about 90% of the total protein content and assembles into fibrils that confer elasticity and tensile strength to bone. These collagen fibrils serve as a scaffold, with their periodic banding pattern directing the oriented deposition of mineral crystals. Non-collagenous proteins, comprising the remaining 10% of the matrix proteins, include osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein, which regulate mineralization by binding calcium ions and initiating crystal nucleation at specific sites along collagen fibers. Glycosaminoglycans, such as chondroitin sulfate, are minor constituents that enhance matrix hydration, modulate collagen fibril assembly, and contribute to bone toughness by influencing mineral distribution and preventing excessive brittleness.[22][24][25] The inorganic phase primarily consists of hydroxyapatite crystals, with the chemical formula , which embed within the organic matrix to provide compressive strength and overall stiffness. These nanoscale platelets, approximately 50-100 nm long and 20-50 nm wide, align parallel to collagen fibrils, optimizing load transfer. Trace elements, including magnesium and fluoride, substitute for calcium in the hydroxyapatite lattice or adsorb onto crystal surfaces, thereby influencing crystal size, solubility, and growth kinetics; for instance, magnesium inhibits excessive crystal perfection to maintain some solubility for remodeling, while fluoride promotes denser crystal formation but can reduce mechanical toughness at high levels.[26][27] The interplay of these components yields distinct biomechanical properties, such as a Young's modulus of 10-20 GPa for cortical bone, reflecting its stiffness under elastic deformation. Bone exhibits anisotropic behavior, with compressive strength (up to 170 MPa) exceeding tensile strength (about 120 MPa) due to the composite architecture, where mineral reinforces collagen against buckling while the organic phase resists crack propagation.[28] Mineral deposition in bone follows a tightly regulated process beginning with nucleation on collagen fibrils, particularly at hole zones within the fibril structure, where non-collagenous proteins like bone sialoprotein concentrate ions to form initial amorphous calcium phosphate clusters. This is followed by epitaxial growth, where crystals expand along the collagen axis, transforming into mature hydroxyapatite plates. Alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme secreted by osteoblasts, plays a crucial role by hydrolyzing inorganic pyrophosphate—a potent mineralization inhibitor—thereby elevating local phosphate levels to drive crystal formation and prevent pathological calcification elsewhere.[29][30]Development and Growth

Embryonic Development