Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Winnetou

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

| Winnetou | |

|---|---|

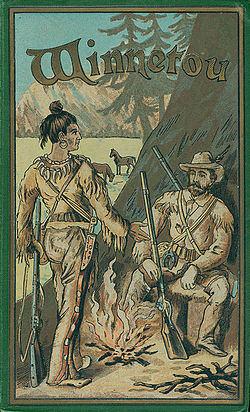

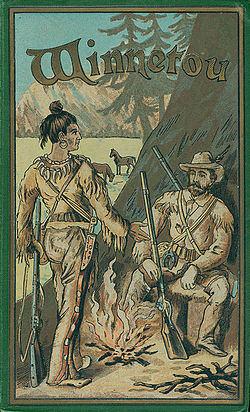

Cover of 1893 edition | |

| Created by | Karl May |

| Portrayed by | Pierre Brice, Nik Xhelilaj |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Tribal Leader |

Winnetou is a fictional Native American hero of several novels written in German by Karl May (1842–1912), one of the best-selling German writers of all time with about 200 million copies worldwide, including the Winnetou trilogy. The character made his debut in the novel Old Firehand (1875).

Stories

[edit]In May's story, first-person narrator Old Shatterhand encounters the Apache Winnetou, and after initial dramatic events, a true friendship arises between them. On many occasions, they give proof of great fighting skill, but also of compassion for other human beings. May portrays a belief in an innate "goodness" of humankind, albeit constantly threatened by ill-intentioned enemies.

Nondogmatic Christian feelings and values play an important role, and May's heroes are often described as German Americans.

Winnetou became the chief of the tribe of the Mescalero Apaches (and of the Apaches in general, with the Navajo included) after his father Intschu-tschuna and his sister Nscho-tschi were slain by the white bandit Santer. He rode a horse called Iltschi ('wind') and had a famous rifle called Silberbüchse ('silver rifle'), a double-barrelled rifle whose stock and butt were decorated with silver studs. Old Shatterhand became the blood brother of Winnetou and rode the brother of Iltschi, called Hatatitla ('lightning'). In a number of adaptations, Winnetou referred to himself in the third person.[1][2]

Themes

[edit]

Karl May's Winnetou novels symbolize, to some extent, a romantic desire for a simpler life in close contact with nature. The popularity of the series is due in large part to the ability of the stories to tantalize fantasies many Europeans had and have for this more untamed environment. The sequel has become the origin of festivals, and the first regular Karl-May-Spiele were staged 1938 till 1941 in Rathen, Saxony. East Germany restarted those open-air theater plays in 1984. In West Germany, the Karl-May-Festspiele in Bad Segeberg were started as early as 1950 and then expanded to further places like Lennestadt-Elspe in honor of Karl May's Apache hero, Winnetou.

The stories were so popular that Nazi Germany did not ban them; instead, the argument was made that the stories demonstrated the fall of the American aboriginal peoples was caused by a lack of racial consciousness.[3]

May's heroes drew on archetypes of Germanic culture and had little to do with actual Native American cultures. "Winnetou is noble because he combines the highest aspects of otherwise 'decadent' Indian cultures with the natural adoption of the romantic and Christian traits of Karl May's own vision of German civilization. As he is dying, the Apache Winnetou asks some settlers to sing an Ave Maria for him, and his death is sanctified by his quiet conversion to Christianity."[4]

In the 1960s, French nobleman and actor Pierre Brice played Winnetou in several movies coproduced by West German–Yugoslav producers. At first, Brice was not very excited about the role beside Lex Barker, but his very reduced text and stage play brought Winnetou to real life in West Germany. Brice not only became a star in West Germany, but a significant contributor to German–French reconciliation, as well.

Original German Winnetou stories

[edit]Travel stories

[edit]- Old Firehand (1875)

- Winnetou (1878, titular character Inn-nu-wo, der Indianerhäuptling (1875) is changed)

- Im fernen Westen (1879, revision of Old Firehand, later revised for Winnetou II)

- Deadly Dust (1880, later revised for Winnetou III)

- Die Both Shatters (1882)

- Ein Oelbrand (1882/83)

- Im "wilden Westen" Nordamerika's (1882/83, later revised for Winnetou III)

- Der Scout (1888/89, later revised for Winnetou II)

- Winnetou I (1893, temporarily also entitled as Winnetou der Rote Gentleman I)

- Winnetou II (1893, temporarily also entitled as Winnetou der Rote Gentleman II)

- Winnetou III (1893, temporarily also entitled as Winnetou der Rote Gentleman III)

- Old Surehand I (1894)

- Old Surehand II (1895)

- Old Surehand III (1896)

- Satan und Ischariot I (1896)

- Satan und Ischariot II (1897)

- Satan und Ischariot III (1897)

- Gott läßt sich nicht spotten (within Auf fremden Pfaden, 1897)

- Ein Blizzard (within Auf fremden Pfaden, 1897)

- Mutterliebe (1897/98)

- Weihnacht! (1897)

- Winnetou IV (1910)

Juvenile fiction

[edit]- Im fernen Westen (1879, revision of Old Firehand)

- Unter der Windhose (1886, later also within Old Surehand II)

- Der Sohn des Bärenjägers (1887, within Die Helden des Westens since 1890)

- Der Geist des Llano estakado (1888, within Die Helden des Westens since 1890)

- Der Schatz im Silbersee (1890/91)

- Der Oelprinz (1893/94)

- Der schwarze Mustang (1896/97)

Other works

[edit]- Auf der See gefangen (1878/1879, also entitled as Auf hoher See gefangen)

Comic strip adaptations

[edit]In the 1950s Yugoslavian comic book artist Walter Neugebauer finished his 1930s comic book adaptation of Karl May's stories.[5] Another Yugoslavian artist Aleksandar Hecl also drew one.[6] Belgian comics artist Willy Vandersteen created a whole series of comics based on May's stories, simply titled Karl May (1962–1977).[7] More notable Winnetou comic strip adaptations were done by Spanish writer and artist Juan Arranz for the Dutch comic strip weekly Sjors between 1963 and 1970. Most of these stories were also published in comic strip albums and were syndicated to other European countries. Two Hungarian authors named Horváth Tibor and Zórád Ernö collaborated on yet another comic version in 1957. In West Germany, Helmut Nickel also adapted the source material, published bi-weekly from 1962 to 1966.[8]

Karl May movies with the Winnetou character

[edit]In all these movies, Winnetou was played by French actor Pierre Brice, who was wearing Redface, and was usually teamed with Lex Barker as Old Shatterhand. The music for all Winnetou movies (with its famous title melody played on the harmonica by Johnny Müller) was composed by German composer Martin Böttcher, except Old Shatterhand, composed by Italian composer Riz Ortolani, and Winnetou und sein Freund Old Firehand, composed by German composer Peter Thomas. The films were so successful in West Germany, their budgets could be increased almost every time. Principal shooting usually took place in Paklenica karst river canyon national park, Croatia. The early films preceded the Spaghetti Western.

- Der Schatz im Silbersee (1962) — Treasure of Silver Lake (1965) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Winnetou 1. Teil (1963) — Apache Gold (1965) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Old Shatterhand (1964) — Apaches' Last Battle (1964) (UK - Yugoslavia)

- Winnetou – 2. Teil (1964) — Last of the Renegades (1966) (UK - West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Unter Geiern (1964) — Frontier Hellcat (1966) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Der Ölprinz (1965) — Rampage at Apache Wells (1965) (Yugoslavia)

- Winnetou – 3. Teil (1965) — Winnetou: The Desperado Trail (1965) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Old Surehand 1. Teil (1965) — Flaming Frontier (1969) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Winnetou und das Halbblut Apanatschi (1966) — Winnetou and the Crossbreed (1973) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Winnetou und sein Freund Old Firehand (1966) — Winnetou and Old Firehand a.k.a. Thunder at the Border (1966) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

- Winnetou und Shatterhand im Tal der Toten (1968) — The Valley of Death (1968) (West Germany - Yugoslavia)

All of the Winnetou movies are available on VHS tape in PAL format – some also dubbed in English under the above-mentioned English titles. Winnetou I–III, Der Schatz im Silbersee, Old Shatterhand, and Winnetou und Shatterhand im Tal der Toten are also available on DVD (region-code 2), but all in German only. In 2004–2005, the missing movies were also to reappear on DVD. In 2016 a Blu-ray box with all Winnetou movies was released; they also were made available as part of the Karl May Blu-ray box.

In April 2009, DVDs of the cleared remastered movies were issued in the Czech Republic, selling as an add-on to the Metro newspaper for 50 Czech crowns. All movies are dubbed into Czech and German, with subtitles in Czech and Slovak.

Television miniseries

[edit]Also in these television series, Winnetou was played by Brice.

- Mein Freund Winnetou (1980) — My friend Winnetou — Winnetou le Mescalero, 7 episodes at 52 min.

- Winnetous Rückkehr ("The Return of Winnetou") (1998), 2 parts, 171 min. in total

- CBC Documentary[9][full citation needed]

In 2016, Winnetou was published, a modernized version of the classic movies in three parts directed by Philipp Stölzl, starring Nik Xhelilaj as Winnetou.[10]

In popular culture

[edit]- The artwork for Gang of Four's album Entertainment! features a heavily processed image from a Winnetou film.

- The song "Mein Bester Freund" ("My Best Friend") on the 1991 Die Prinzen album Das Leben ist grausam refers to Winnetou in a short list of heroes, alongside Robin Hood and Sherlock Holmes.

- In 2001, a parody of the Winnetou films, Der Schuh des Manitu, was directed by Michael Herbig. This movie is based on various sketches of Herbig's TV show Bullyparade. In Bullyparade – Der Film, which was also directed by Herbig, Winnetou is one of the main characters of the episode Winnetou in Love.

- Director Quentin Tarantino mentioned Winnetou in his 2009 film Inglourious Basterds.

- Music Duo Abor & Tynna's 11th Song on the "Bittersüß" ("Bittersweet") Album is named "Winnetou."

References

[edit]- ^ "'Winnetou' actor Pierre Brice dies". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "Seeking the Aboriginal experience in Germany". windspeaker.com. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p. 79 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ "Foreign Views (7 of 9)". bancroft.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ "Walter Neugebauer". lambiek.net. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "[Projekat Rastko] Zdravko Zupan: Strip u Srbiji 1955–1972". www.rastko.rs. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ "Willy Vandersteen". lambiek.net. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ "E-Fachmagazin für Comic-Kultur & Bildgeschichte – unabhängig, innovativ und weltoffen". COMICOSKOP – Unabhängiges E-Fachmagazin für Comic-Kultur & Bildgeschichte (in German). Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ https://www.cbc.ca/cbcdocspov/episodes/searching-for-winnetou [bare URL]

- ^ [1] Archived 20 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine MMC Studios, The Myth Lives on!, Announcement 2016]

Further reading

[edit]- Perry, Nicole (McGill University Department of German Studies). "Karl May's Winnetou: The Image of the German Indian. The Representation of North American First Nations from an Orientalist Perspective" (Archive). August 2006. – Info page

- Scott, Emily (University of Missouri Department of History). "Fiction and Politics: Karl May and the American West in Nineteenth Century German Sociopolitical Consciousness, May 2018."

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Winnetou at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Winnetou at Wikimedia Commons

Winnetou

View on GrokipediaWinnetou is a fictional Mescalero Apache chief and warrior created by German author Karl May as the noble protagonist and blood brother of the narrator Old Shatterhand in a trilogy of adventure novels set in the 19th-century American West.[1][2]

The stories, published between 1893 and 1894, depict Winnetou as an idealized figure of integrity, physical prowess, and spiritual harmony with nature, who combats greed, injustice, and treachery alongside his German companion, drawing from May's imaginative synthesis of travel accounts despite the author's lack of firsthand experience in America until 1908.[3][2][4] These works achieved enduring popularity in Europe, inspiring theatrical performances, radio dramas, and a series of 1960s films directed by Harald Reinl and starring Pierre Brice as Winnetou, which emphasized themes of interracial brotherhood and moral heroism.[5][1] In recent decades, Winnetou's romanticized portrayal has sparked controversy, with critics arguing it perpetuates stereotypes of Native Americans as exotic primitives subservient to white narratives; this led a German publisher to withdraw children's editions in 2022 amid social media-driven accusations of racism, though defenders contend the character's elevation of indigenous virtue challenges rather than endorses colonial hierarchies.[6][7][8]