Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Yamnaya culture

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Alternative names |

|

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Pontic–Caspian steppe in Europe |

| Period | Copper Age, Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 3300–2600 BC |

| Preceded by | Sredny Stog culture, Samara culture, Khvalynsk culture, Dnieper–Donets culture, Repin culture, Maykop culture, Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, Cernavodă culture, Usatove culture, Novosvobodnaya culture, Mykhailivka culture (3600–3000 BCE) |

| Followed by |

|

| Defined by | Vasily Gorodtsov |

The Yamnaya (/ˈjæmnaɪə/ YAM-ny-ə) or Yamna culture (/ˈjæmnə/ YAM-nə),[a] also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–Caspian steppe), dating to 3300–2600 BC.[2] It was discovered by Vasily Gorodtsov following his archaeological excavations near the Donets River in 1901–1903. Its name derives from its characteristic burial tradition: yámnaya (я́мная) is a Russian adjective that means 'related to pits' (я́ма, yáma), as these people buried their dead in tumuli (kurgans) containing simple pit chambers. Research in recent years has found that Mykhailivka, on the lower Dnieper River, Ukraine, formed the core Yamnaya culture (c. 3600–3400 BC).[3][4][5][6]

The Yamnaya culture is of particular interest to archaeologists and linguists, as the widely accepted Kurgan hypothesis posits that the people who produced the Yamnaya culture spoke a stage of the Proto-Indo-European language. The speakers of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language embarked on the Indo-European migrations that gave rise to the widely dispersed Indo-European languages of today.

The Yamnaya economy was based upon animal husbandry, fishing, and foraging, and the manufacture of ceramics, tools, and weapons.[7] The people of the Yamnaya culture lived primarily as nomads, with a chiefdom system and wheeled carts and wagons that allowed them to manage large herds.[8] They are also closely connected to Final Neolithic cultures, which later spread throughout Europe and Central Asia, especially the Corded Ware people and the Bell Beaker culture,[8] as well as the peoples of the Sintashta, Andronovo, and Srubnaya cultures. Back migration from Corded Ware also contributed to Sintashta and Andronovo.[9] In these groups, several aspects of the Yamnaya culture are present.[b] Yamnaya material culture was very similar to the Afanasievo culture of South Siberia, and the populations of the two cultures are genetically indistinguishable.[1] This suggests that the Afanasievo culture may have originated from the migration of Yamnaya groups to the Altai region or, alternatively, that both cultures developed from an earlier shared cultural source.[10]

Genetic studies have suggested that the people of the Yamnaya culture can be modelled as a genetic admixture between a population related to Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers (EHG)[c] and people related to hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus (CHG) in roughly equal proportions,[11] an ancestral component which is often named "Steppe ancestry", with additional admixture from Anatolian, Levantine, or Early European farmers.[12][13] Genetic studies also indicate that populations associated with the Corded Ware, Bell Beaker, Sintashta, and Andronovo cultures derived large parts of their ancestry from the Yamnaya or a closely related population.[1][14][15][16] Recent genetic analyses indicate that the Anatolian component in the Yamnaya comes via the Caucasus Neolithic population and not Anatolia-derived European farmers.[17]

Origins

[edit]

The Yamnaya culture was defined by Vasily Gorodtsov in order to differentiate it from the Catacomb and Srubnaya cultures that existed in the area, but were considered to be of a later period. Due to the time interval to the Yamnaya culture, and the reliance on archaeological findings, debate as to its origin is ongoing.[23] In 1996, Pavel Dolukhanov suggested that the emergence of the Pit-Grave culture represents a social development of various different local Bronze Age cultures, thus representing "an expression of social stratification and the emergence of chiefdom-type nomadic social structures" which in turn intensified inter-group contacts between essentially heterogeneous social groups.[24]

The origin of the Yamnaya culture continues to be debated, with proposals for its origins pointing to both the Khvalynsk and Sredny Stog cultures.[23] The Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BC)[25] (middle Volga) and the Don-based Repin culture (c. 3950–3300 BC)[26] in the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe, and the closely related Sredny Stog culture (c. 4500–3500 BC) in the western Pontic-Caspian steppe, preceded the Yamnaya culture (3300–2500 BC).[27][28]

Further efforts to pinpoint the location came from Anthony (2007), who suggested that the Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BC) originated in the Don–Volga area at c. 3400 BC,[29][2] preceded by the middle Volga-based Khvalynsk culture and the Don-based Repin culture (c. 3950–3300 BC),[26][2] arguing that late pottery from these two cultures can barely be distinguished from early Yamnaya pottery.[30] Earlier continuity from eneolithic but largely hunter-gatherer Samara culture and influences from the more agricultural Dnieper–Donets II are apparent.

He argues that the early Yamnaya horizon spread quickly across the Pontic–Caspian steppes between c. 3400 and 3200 BC:[29]

The spread of the Yamnaya horizon was the material expression of the spread of late Proto-Indo-European across the Pontic–Caspian steppes.[31]

[...] The Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility – the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes.[32]

Alternatively, Parpola (2015) relates both the Corded ware culture and the Yamnaya culture to the late Trypillia (Tripolye) culture.[33] He hypothesizes that "the Tripolye culture was taken over by PIE speakers by c. 4000 BC",[34] and that in its final phase the Trypillian culture expanded to the steppes, morphing into various regional cultures which fused with the late Sredny Stog (Serednii Stih) pastoralist cultures, which, he suggests, gave rise to the Yamnaya culture.[35] Dmytro Telegin viewed Sredny Stog and Yamnaya as one cultural continuum and considered Sredny Stog to be the genetic foundation of the Yamna.[36] Telegin's view has been recently confirmed by genetic analyses.[17][5]

The Yamnaya culture was succeeded in its western range by the Catacomb culture (2800–2200 BC); in the east, by the Poltavka culture (2700–2100 BC) at the middle Volga. These two cultures were followed by the Srubnaya culture (18th–12th century BC).

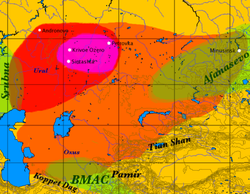

- Maps of the origins of Yamnaya culture

-

Sredny Stog culture (c. 4500–3500 BC)

-

Usatovo culture (c. 3500–3000 BC)

-

Khvalynsk culture (c. 4900–3500 BC)

-

Early Yamnaya culture (3400 BC), according to Anthony (2007)

-

Mykhailivka culture (c. 3600–3400 BC)

Characteristics

[edit]

The Yamnaya culture was nomadic[8] or semi-nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers, and a few fortified sites, the largest of which is Mikhaylivka.[37]

Characteristic of the culture are the burials in pit graves surmounted by kurgans (tumuli), often accompanied by animal offerings. Some graves contain large anthropomorphic stelae, with carved human heads, arms, hands, belts, and weapons.[38] The bodies were placed in a supine position with bent knees and covered in ochre. Some kurgans contained "stratified sequences of graves".[39] Kurgan burials may have been rare, and were perhaps reserved for special adults, who were predominantly male.[40] Status and gender are marked by grave goods and position, and in some areas, elite individuals are buried with complete wooden wagons.[41] Grave goods are more common in eastern Yamnaya burials, which are also characterized by a higher proportion of male burials and more male-centred rituals than western areas.[42]

The Yamnaya culture had and used two-wheeled carts and four-wheeled wagons, which are thought to have been oxen-drawn at this time, and there is evidence that they rode horses.[43][44] For instance, several Yamnaya skeletons exhibit specific characteristics in their bone morphology that may have been caused by long-term horseriding.[43] The evidence is disputed by archaeozoologist William T. Taylor, who argues that domestication of the horse long postdates the Yamnaya culture.[45] Recent genetic studies indicate that horse domestication in Eurasia happened after c. 2700 BC.[46]

Metallurgists and other craftsmen are given a special status in Yamnaya society, and metal objects are sometimes found in large quantities in elite graves. New metalworking technologies and weapon designs are used.[41]

Stable isotope ratios of Yamnaya individuals from the Dnipro Valley suggest the Yamnaya diet was terrestrial protein based with insignificant contribution from freshwater or aquatic resources.[47] Anthony speculates that the Yamnaya ate meat, milk, yogurt, cheese, and soups made from seeds and wild vegetables, and probably consumed mead.[48]

Mallory and Adams suggest that Yamnaya society may have had a tripartite structure of three differentiated social classes, although the evidence available does not demonstrate the existence of specific classes such as priests, warriors, and farmers.[49]

Gallery

[edit]-

Daggers, arrowheads and bone artefacts

-

Yamnaya decorative artifacts

-

The Kernosivsky idol (late Yamnaya)

-

Western Yamnaya artefacts

-

Yamnaya burials from Moldova

-

Copper alloy artifacts at the Hermitage Museum

-

Silver and gold jewellery from Bulgaria

-

Yamnaya pottery

-

Corded ware vessel

-

Yamnaya artefacts from the steppe-Urals, early (1) and late (2)

-

Copper, gold and silver artefacts from western Ukraine

Archaeogenetics

[edit]

According to Jones et al. (2015) and Haak et al. (2015), autosomal tests indicate that the Yamnaya people were the result of a genetic admixture between two different hunter-gatherer populations: distinctive "Eastern Hunter-Gatherers" (EHG), from Eastern Europe, with high affinity to the Mal'ta–Buret' culture or other, closely related people from Siberia[14] and a population of "Caucasus hunter-gatherers" (CHG) who probably arrived from the Caucasus[52][11] or Iran.[53] Each of those two populations contributed about half the Yamnaya DNA.[15][11] This admixture is referred to in archaeogenetics as Western Steppe Herder (WSH) ancestry.

Admixture between EHGs and CHGs is believed to have occurred on the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe starting around 5,000 BC, while admixture with Early European Farmers (EEF) happened in the southern parts of the Pontic-Caspian steppe sometime later. More recent genetic studies have found that the Yamnaya were a mixture of EHGs, CHGs, and to a lesser degree Anatolian farmers and Levantine farmers, but not EEFs from Europe due to lack of WHG DNA in the Yamnaya. This occurred in two distinct admixture events from West Asia into the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[13][54]

Haplogroup R1b, specifically the Z2103 subclade of R1b-L23, is the most common Y-DNA haplogroup found among the Yamnaya specimens. This haplogroup is rare in Western Europe and mainly exists in Southeastern Europe today.[56] Additionally, a minority are found to belong to haplogroup J2 and I2.[15][5] They are found to belong to a wider variety of West Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups, including U, T, and haplogroups associated with Caucasus hunter-gatherers and Early European Farmers.[12][57] A small but significant number of Yamnaya kurgan specimens from Northern Ukraine carried the East Asian mtDNA haplogroup C4.[58][59]

People of the Yamnaya culture are believed to have had mostly brown eye colour, light to intermediate skin, and brown hair colour, with some variation.[60][61]

Some Yamnaya individuals are believed to have carried a mutation to the KITLG gene associated with blond hair, as several individuals with Steppe ancestry are later found to carry this mutation. The Ancient North Eurasian Afontova Gora group, who contributed significant ancestry to Western Steppe Herders, are believed to be the source of this mutation.[62] A study in 2015 found that Yamnaya had the highest ever calculated genetic selection for height of any of the ancient populations tested.[63][64] It has been hypothesized that an allele associated with lactase persistence (conferring lactose tolerance into adulthood) was brought to Europe from the steppe by Yamnaya-related migrations.[65][66][67][68]

A 2022 study by Lazaridis et al. found that the typical phenotype among the Yamnaya population was brown eyes, brown hair, and intermediate skin colour. None of their Yamnaya samples were predicted to have either blue eyes or blond hair, in contrast with later Steppe groups in Russia and Central Asia, as well as the Bell Beaker culture in Europe, who did carry these phenotypes in significant proportions.[13]

The geneticist David Reich has argued that the genetic data supports the likelihood that the people of the Yamnaya culture were a "single, genetically coherent group" who were responsible for spreading many Indo-European languages.[69] Reich's group recently suggested that the source of Anatolian and Indo-European subfamilies of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language may have been in west Asia and the Yamnaya were responsible for the dissemination of the latter.[5] Reich also argues that the genetic evidence shows that Yamnaya society was an oligarchy dominated by a small number of elite males.[70] Recent (2024 and 2025) publications confirmed the tight clustering of most of Yamnaya genetic profiles, but shifted the origins of PIE towards the Caucasus-Lower Volga (CLV) region.[17][5]

The genetic evidence for the extent of the role of the Yamnaya culture in the spread of Indo-European languages has been questioned by Russian archaeologist Leo Klejn[71] and Balanovsky et al.,[72] who note a lack of male haplogroup continuity between the people of the Yamnaya culture and the contemporary populations of Europe. Klejn has also suggested that the autosomal evidence does not support a Yamnaya migration, arguing that Western Steppe Herder ancestry in both contemporary and Bronze Age samples is lowest around the Danube in Hungary, near the western limits of the Yamnaya culture, and highest in Northern Europe, which Klejn argues is the opposite of what would be expected if the geneticists' hypothesis is correct.[73]

Language

[edit]Marija Gimbutas identified the Yamnaya culture with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) in her Kurgan hypothesis. In the view of David Anthony, the Pontic-Caspian steppe is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language, citing evidence from linguistics and genetics[14][74] which suggests that the Yamnaya culture may be the homeland of the Indo-European languages, with the possible exception of the Anatolian languages.[75][76] On the other hand, Colin Renfrew has argued for a Near Eastern origin of the earliest Indo-European speakers.[77][78]

According to David W. Anthony, the genetic evidence suggests that the leading clans of the Yamnaya were of EHG (Eastern European hunter-gatherer) and WHG (Western European hunter-gatherer) paternal origin[79] and implies that the Indo-European languages were the result of "a dominant language spoken by EHGs that absorbed Caucasus-like elements in phonology, morphology, and lexicon."[80] It has also been suggested that the PIE language evolved through trade interactions in the circum-Pontic area in the 4th millennium BC, mediated by the Yamnaya predecessors in the North Pontic steppe.[81]

Guus Kroonen et al. 2022 found that the "basal Indo-European stage", also known as Indo-Anatolian or Pre-Proto-Indo-European language, largely but not totally, lacked agricultural-related vocabulary, and only the later "core Indo-European languages" saw an increase in agriculture-associated words. According to them, this fits a homeland of early core Indo-European within the westernmost Yamnaya horizon, around and west of the Dnieper, while its basal stage, Indo-Anatolian, may have originated in the Sredny Stog culture, as opposed to the eastern Yamnaya horizon. The Corded Ware culture may have acted as major source for the spread of later Indo-European languages, including Indo-Iranian, while Tocharian languages may have been mediated via the Catacomb culture. They also argue that this new data contradicts a possible earlier origin of Pre-Proto-Indo-European among agricultural societies South of the Caucasus, rather "this may support a scenario of linguistic continuity of local non-mobile herders in the Lower Dnieper region and their genetic persistence after their integration into the successive and expansive Yamnaya horizon". Furthermore, the authors mention that this scenario can explain the difference in paternal haplogroup frequency between the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures, while both sharing similar autosomal DNA ancestry.[82]

Yamnaya-related migrations

[edit]

Western Europe

[edit]Genetic studies have found that Yamnaya autosomal characteristics are very close to the Corded Ware culture people, with up to 75% Yamnaya-like ancestry in the DNA of Corded Ware skeletons from Central and Eastern Europe.[83] Yamnaya–related ancestry is found in the DNA of modern Central, and Northern Europeans (c. 38.8–50.4%), and is also found in lower levels in present-day Southern Europeans (c. 18.5–32.6%), Sardinians (c. 2.4–7.1%), and Sicilians (c. 5.9–11.6%).[84][74][16]

However, according to Heyd, et al. (2023), the specific paternal DNA haplogroup that is most commonly found in male Yamnaya specimens cannot be found in modern Western Europeans, or in males from the nearby Corded Ware culture. This makes it unlikely that the Corded Ware culture can be directly descended from the Yamnaya culture, at least along the paternal line.[85]

Autosomal tests also indicate that the Yamnaya are the vector for "Ancient North Eurasian" admixture into Europe.[14] "Ancient North Eurasian" is the name given in literature to a genetic component that represents descent from the people of the Mal'ta–Buret' culture[14] or a population closely related to them. That genetic component is visible in tests of the Yamnaya people[14] as well as modern-day Europeans.[86]

Eastern Europe and Finland

[edit]

In the Baltic, Jones et al. (2017) found that the Neolithic transition – the passage from a hunter-gatherer economy to a farming-based economy – coincided with the arrival en masse of individuals with Yamnaya-like ancestry. This is different from what happened in Western and Southern Europe, where the Neolithic transition was caused by a population that came from Anatolia, with Pontic steppe ancestry being detected from only the late Neolithic onward.[87]

Per Haak et al. (2015), the Yamnaya contribution in the modern populations of Eastern Europe ranges from 46.8% among Russians to 42.8% in Ukrainians. Finland has the highest Yamnaya contributions in all of Europe (50.4%).[88][d]

Central and South Asia

[edit]

There is a significant presence of Yamnaya descent in the nations of South Asia, especially in groups that are referred to as Indo-Aryans.[89][90] Lazaridis et al. (2016) estimated (6.5–50.2%) steppe-related admixture in South Asians, though the proportion of Steppe ancestry varies widely across ethnic groups.[53][e] According to Pathak et al. (2018), the "North-Western Indian & Pakistani" populations (PNWI) showed significant Middle-Late Bronze Age Steppe (Steppe_MLBA) ancestry along with Yamnaya Early-Middle Bronze Age (Steppe_EMBA) ancestry, but the Indo-Europeans of Gangetic Plains and Dravidian people only showed significant Yamnaya (Steppe_EMBA) ancestry and no Steppe_MLBA. The study also noted that ancient south Asian samples had significantly higher Steppe_MLBA than Steppe_EMBA (or Yamnaya).[90][f] According to Narasimhan et al. (2019), the Yamnaya-related ancestry, termed Western_Steppe_EMBA, that reached central and south Asia was not the initial expansion from the steppe to the east, but a secondary expansion that involved a group possessing c. 67% Western_Steppe_EMBA ancestry and c. 33% ancestry from the European cline. This group included people similar to that of Corded Ware, Srubnaya, Petrovka, and Sintashta. Moving further east in the central steppe, it acquired c. 9% ancestry from a group of people that possessed West Siberian Hunter Gatherer ancestry, thus forming the Central Steppe MLBA cluster, which is the primary source of steppe ancestry in South Asia, contributing up to 30% of the ancestry of the modern groups in the region.[89]

According to Unterländer et al. (2017), all Iron Age Scythian Steppe nomads can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian–related component, which most closely corresponds to the modern North Siberian Nganasan people of the lower Yenisey River, to varying degrees, but generally higher among Eastern Scythians.[91]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Я́мная культу́ра, romanized: Yámnaya kultúra, pronounced [ˈjamnəjə kʊlʲˈturə]; Ukrainian: Я́мна культу́ра, romanized: Yámna kuľtúra, pronounced [ˈjɑmnɐ kʊlʲˈturɐ]; lit. 'culture of pits', from я́ма 'pit, hole'.

- ^ Yamnayan cultural aspects, for example, were horse-riding, burial styles, and to some extent the pastoralist economy.

- ^ The Eastern European hunter-gatherers were themselves mostly descended from ancient North Eurasians, related to the palaeolithic Mal'ta–Buret' culture.

- ^ Per Haak et al. (2015), adding a north-Siberian people as a fourth reference population improves residuals for northeastern European populations. This accounts for the higher than expected Yamnaya contribution and brings it down to expected levels (67.8–50.4 % in Finns, 64.9–46.8 % in Russians).

- ^ Lazaridis et al. (2016) Supplementary Information, Table S9.1: "Kalash – 50.2 %, Tiwari Brahmins – 44.1 %, Gujarati (four sample sets) – 46.1 % to 27.5 %, Pathan – 44.6 %, Burusho – 42.5 %, Sindhi – 37.7 %, Punjabi – 32.6 %, Balochi – 32.4 %, Brahui – 30.2 %, Lodhi – 29.3 %, Bengali – 24.6 %, Vishwabhramin – 20.4 %, Makrani – 19.2 %, Mala – 18.4 %, Kusunda – 8.9 %, Kharia – 6.5 %."

- ^ Pathak et al. (2018) "The Ror and Jat peoples stand out for having the highest proportion of Steppe_MLBA ancestry (∼63%)"

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Allentoft et al. 2015.

- ^ a b c Morgunova & Khokhlova 2013.

- ^ Reich, David (24 April 2024). "The Genetic Origin of the Indo-Europeans". The Transformation of Europe in the Third Millennium BC. Budapest: International Conference, HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeology.

- ^ Nikitin et al. 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Lazaridis et al. 2025.

- ^ Saag & Metspalu 2025.

- ^ Shishlina 2023.

- ^ a b c Anthony 2023.

- ^ Novembre 2015, "evidence to support theories of a back-migration from Corded Ware-related populations that contributed to the origins of the Sintashta culture in the Urals and their descendants, the Andronovo."

- ^ Hermes et al. 2020.

- ^ a b c "Europe's fourth ancestral 'tribe' uncovered". BBC. 16 November 2015.

- ^ a b Wang et al. 2019.

- ^ a b c Lazaridis et al. 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Haak et al. 2015.

- ^ a b c Mathieson, et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Gibbons, Ann (10 June 2015). "Nomadic herders left a strong genetic mark on Europeans and Asians". Science. AAAS.

- ^ a b c Nikitin et al. 2024.

- ^ Nikitin et al. 2017.

- ^ Nikitin et al. 2017.

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 300–370.

- ^ Nordgvist & Heyd 2020.

- ^ Mallory 1999.

- ^ a b Mallory 1999, p. 215.

- ^ Dolukhanov 1996, p. 94.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 182.

- ^ a b Anthony 2007, p. 275.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 300.

- ^ Mallory 1999, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b Anthony 2007, p. 321.

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 274–277, 317–320.

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 303.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 49.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 45.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Telegin, D. Y. (1973). Serednʹo-stohivsʹka kulʹtura epokhy midi Середньостогівська культура епохи міді [Middle Stogov culture of the Copper Age] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv: Naukova Dumka. p. 147.

- ^ Mallory 1997, p. 212.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 339.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 319.

- ^ Anthony, David. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. pp. 328–329. OCLC 1102387902.

- ^ a b Harrison & Heyd 2007, p. 196.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 305.

- ^ a b Trautmann 2023.

- ^ P., Mallory, J. (2003) [1989]. In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology, and myth. Thames and Hudson. p. 213. ISBN 0-500-27616-1. OCLC 886668216.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor, William T. (December 2024). "When Horse became Steed". Scientific American. 331 (5): 24–30. Bibcode:2024SciAm.331e..22T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican122024-7qfHkaSxwWOJpTcwY2J0bg. PMID 39561067.

- ^ Librado, Pablo; Tressières, Gaetan; Chauvey, Lorelei; Fages, Antoine; Khan, Naveed; Schiavinato, Stéphanie; Calvière-Tonasso, Laure; Kusliy, Mariya A.; Gaunitz, Charleen; Liu, Xuexue; Wagner, Stefanie; Der Sarkissian, Clio; Seguin-Orlando, Andaine; Perdereau, Aude; Aury, Jean-Marc (July 2024). "Widespread horse-based mobility arose around 2200 bce in Eurasia". Nature. 631 (8022): 819–825. Bibcode:2024Natur.631..819L. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07597-5. hdl:10871/136199. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 11269178. PMID 38843826.

- ^ Gerling, Claudia (1 July 2015). Prehistoric Mobility and Diet in the West Eurasian Steppes 3500 to 300 BC: An Isotopic Approach. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110311211. ISBN 978-3-11-031121-1.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 430.

- ^ J. P. Mallory; Douglas Q. Adams, eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 653. ISBN 1-884964-98-2. OCLC 37931209.

- ^ "Cudgel Culture". archaeology.org. 2002.

- ^ Hanel, Andrea; Carlberg, Carsten (3 July 2020). "Skin colour and vitamin D: An update". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (9): 864–875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142. PMID 32621306.

- ^ Jones et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Lazaridis et al. 2016.

- ^ Chintalapati, Manjusha; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya (30 May 2022). Perry, George H (ed.). "The spatiotemporal patterns of major human admixture events during the European Holocene". eLife. 11 e77625. doi:10.7554/eLife.77625. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 9293011. PMID 35635751.

- ^ Wang, Chuan-Chao; Reinhold, Sabine; Kalmykov, Alexey (4 February 2019). "Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 590. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..590W. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6360191. PMID 30713341.

- ^ Balanovsky 2017, p. 437.

- ^ Eske, Allentoft; Morten E. Pokutta; Dalia Willerslev (2015). Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. University of Copenhagen, Denmark. OCLC 1234973657.

- ^ Pilipenko, Aleksandr S.; Trapezov, Rostislav O.; Cherdantsev, Stepan V.; Babenko, Vladimir N.; Nesterova, Marina S.; Pozdnyakov, Dmitri V.; Molodin, Vyacheslav I.; Polosmak, Natalia V. (20 September 2018). "Maternal genetic features of the Iron Age Tagar population from Southern Siberia (1st millennium BC)". PLOS ONE. 13 (9) e0204062. Public Library of Science (PLoS). Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1304062P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204062. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6147448. PMID 30235269.

- ^ Nikitin et al. 2017, "In the 12 successfully haplotyped specimens, 75% of mtDNA lineages consisted of west Eurasian haplogroup U and its U4 and U5 sublineages. Furthermore, we identified a subgroup of east Eurasian haplogroup C in two representatives of the Yamna culture in one of the studied kurgans".

- ^ Gibbons, A. (24 July 2015). "Revolution in human evolution". Science. 349 (6246): 362–366. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..362G. doi:10.1126/science.349.6246.362. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26206910.

- ^ Hanel, Andrea; Carlberg, Carsten (September 2020). "Skin colour and vitamin D: An update". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (9): 864–875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142. ISSN 0906-6705. PMID 32621306.

- ^ Mathieson, Iain; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, Songül; Posth, Cosimo; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Candilio, Francesca; Cheronet, Olivia; Fernandes, Daniel (March 2018). "The genomic history of southeastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- ^ Heyd, Volker (April 2017). "Kossinna's smile". Antiquity. 91 (356): 348–359. doi:10.15184/aqy.2017.21. hdl:10138/255652. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 164376362.

- ^ Mathieson, Iain; Lazaridis, Iosif; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Patterson, Nick; Roodenberg, Songül Alpaslan; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fernandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; Sirak, Kendra (24 December 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- ^ Segurel, Laure (2020). "Why and when was lactase persistence selected for? Insights from Central Asian herders and ancient DNA". PLOS Biology. 18 (6) e3000742. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000742. PMC 7302802. PMID 32511234. "Furthermore, ancient DNA studies found that the LP mutation was absent or very rare in Europe until the end of the Bronze Age [26–29] and appeared first in individuals with steppe ancestry [19,20]. Thus, it was proposed that the mutation originated in Yamnaya-associated populations and arrived later in Europe by migration of these steppe herders."

- ^ Callaway, Ewen. "DNA data explosion lights up the Bronze Age". Nature. "the 101 sequenced individuals, the Yamnaya were most likely to have the DNA variation responsible for lactose tolerance, hinting that the steppe migrants might have eventually introduced the trait to Europe"

- ^ Furholt, Martin (2018). "Massive Migrations? The Impact of Recent DNA Studies on our View of Third Millennium Europe". European Journal of Archaeology. 21 (2): 159–191. doi:10.1017/eaa.2017.43. "For example, one lineage could have a biological evolutionary advantage over the other. Allentoft et al. (2015: 171) have found a remarkably high rate of lactose tolerance among individuals connected to Yamnaya and to Corded Ware, as opposed to the majority of Late Neolithic individuals."

- ^ Saag, L (2020). "Human Genetics: Lactase Persistence in a Battlefield". Current Biology. 30 (21): R1311 – R1313. Bibcode:2020CBio...30R1311S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.087. PMID 33142099. S2CID 226229587.

- ^ Reich, David (2018). Who we are and how we got here: ancient DNA and the new science of the human past. Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0. OCLC 1006478846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Reich, David (2018). Who we are and how we got here: ancient DNA and the new science of the human past. Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0. OCLC 1006478846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Klejn, Leo (2017). "The Steppe Hypothesis of Indo-European Origins Remains to be Proven". Acta Archaeologica. 88 (1): 193–204. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0390.2017.12184.x.

- ^ Balanovsky, O. (2017). "Genetic differentiation between upland and lowland populations shapes the Y-chromosomal landscape of West Asia". Human Genetics. 136 (4): 437–450. doi:10.1007/s00439-017-1770-2. PMID 28281087. S2CID 3735168. "The ancient Yamnaya samples are located on the "eastern" R-GG400 branch of haplogroup R1b-L23, showing that the paternal descendants of the Yamnaya still live in the Pontic steppe and that the ancient Yamnaya population was not an important source of paternal lineages in present-day West Europeans."

- ^ Klejn 2017, p. 201: "In the tables presented in the article by Reichs' team (Haak et al. 2015) the genetic pool connecting the Yamnaya culture with the Corded Ware people is shown to be more intense in Northern Europe (Norway and Sweden) and decreases gradually from the North to the South (Fig. 6). It is weakest around the Danube, in Hungary, i. e. areas neighbouring the western branch of the Yamnaya culture! This is the reverse image to what the proposed hypothesis by the geneticists would lead us to expect. It is true that this gradient is traced back from the contemporary materials, but it was already present during the Bronze Age [...]"

- ^ a b Zimmer, Carl (10 June 2015). "DNA Deciphers Roots of Modern Europeans". New York Times. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Olsen, Birgit A.; Olander, Thomas; Kristiansen, Kristian (23 August 2019), Tracing the Indo-Europeans, Oxbow Books, pp. 1–6, doi:10.2307/j.ctvmx3k2h.6, ISBN 978-1-78925-273-6, S2CID 202354040

- ^ Olsen, Birgit A. (11 May 2023), Kristiansen, Kristian; Kroonen, Guus; Willerslev, Eske (eds.), "Marriage Strategies and Fosterage among the Indo-Europeans: A Linguistic Perspective", The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 296–302, doi:10.1017/9781009261753.027, ISBN 978-1-00-926175-3, retrieved 2023-05-13

- ^ Schneider, Thomas (2023). Language Contact in Ancient Egypt. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-3-643-91507-8.

- ^ Russell D. Gray (2024). Cultural Evolution: Society, Technology, Language, and Religion. MIT Press. pp. 295–297. ISBN 978-0-262-55190-8.

- ^ Anthony 2019b, p. 36.

- ^ Anthony 2019a, p. 1-19.

- ^ Nikitin, Alexey; Ivanova, Svetlana (28 November 2022). "Long-distance exchanges along the Black Sea coast in the Eneolithic and the steppe genetic ancestry problem". Cambridge Open Engage. doi:10.33774/coe-2022-7m315.

- ^ Kroonen, Guus; Jakob, Anthony; Palmér, Axel I.; van Sluis, Paulus; Wigman, Andrew (12 October 2022). "Indo-European cereal terminology suggests a Northwest Pontic homeland for the core Indo-European languages". PLOS ONE. 17 (10) e0275744. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1775744K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275744. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9555676. PMID 36223379.

- ^ Stoneking, Mark; Arias, Leonardo; Liu, Dang; Oliveira, Sandra; Pugach, Irina; Rodriguez, Jae Joseph Russell B. (24 January 2023). "Genomic perspectives on human dispersals during the Holocene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (4) e2209475119. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12009475S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2209475119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9942792. PMID 36649433.

- ^ Haak et al. 2015, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Kristiansen, Kristian; Kroonen, Guus; Willerslev, Eske (11 May 2023). The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited: Integrating Archaeology, Genetics, and Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–76. ISBN 978-1-009-26174-6.

How exactly the emergence and expansion of the Corded Ware are linked to the emergence and expansion of the Yamnaya horizon remains unclear. However, the Y chromosome record of both groups indicates that Corded Ware cannot be derived directly from the Yamnaya or late eastern farming groups sampled thus far, and is therefore likely to constitute a parallel development in the forest steppe and temperate forest zones of Eastern Europe.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. 2014.

- ^ Jones et al. 2017.

- ^ Haak et al. 2015, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Narasimhan et al. 2019.

- ^ a b Pathak et al. 2018.

- ^ Unterländer et al. 2017: "Genomic inference reveals that Scythians in the east and the west of the steppe zone can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian component. Demographic modelling suggests independent origins for eastern and western groups with ongoing gene-flow between them, plausibly explaining the striking uniformity of their material culture. We also find evidence that significant gene-flow from east to west Eurasia must have occurred early during the Iron Age. ... The blend of EHG [European hunter-gatherer] and Caucasian elements in carriers of the Yamnaya culture was formed on the European steppe and exported into Central Asia and Siberia. We therefore considered an alternative model in which we treat them as a mix of Yamnaya and the Han (Supplementary Table 25). This model fits all of the Iron Age Scythian groups, consistent with these groups having ancestry related to East Asians not found in the other populations. Alternatively, the Iron Age Scythian groups can also be modelled as a mix of Yamnaya and the north Siberian Nganasan (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 26)."[check quotation syntax]

Sources

[edit]- Allentoft, Morten E.; et al. (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Anthony, David (2017). "Archaeology and Language: Why Archaeologists Care About the Indo-European Problem". In Crabtree, P.J.; Bogucki, P. (eds.). European Archaeology as Anthropology: Essays in Memory of Bernard Wailes.

- Anthony, David (Spring–Summer 2019a). "Archaeology, Genetics, and Language in the Steppes: A Comment on Bomhard". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 47 (1–2). Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- Anthony, David W. (2019b). "Ancient DNA, Mating Networks, and the Anatolian Split". In Serangeli, Matilde; Olander, Thomas (eds.). Dispersals and Diversification: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Early Stages of Indo-European. BRILL. pp. 21–54. ISBN 978-90-04-41619-2.

- Anthony, David W. (11 May 2023). "The Yamnaya Culture and the Invention of Nomadic Pastoralism in the Eurasian Steppes". In Kristiansen, Kristian; Kroonen, Guus; Willerslev, Eske (eds.). The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–33. doi:10.1017/9781009261753.005. ISBN 978-1-00-926175-3. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- Cassidy LM, Martiniano R, Murphy EM, Teasdale MD, Mallory J, Hartwell B, Bradley DG (2016). "Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome". PNAS. 113 (2): 368–373. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..368C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518445113. PMC 4720318. PMID 26712024.

- Dolukhanov, Pavel M. (1996), The Early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the Initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus, New York: Longman, ISBN 0-582-23627-4

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004), Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, Blackwell Publishing

- Gallego-Llorente M, Connell S, Jones ER, Merrett DC, Jeon Y, Eriksson A, et al. (2016). "The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran". Scientific Reports. 6 31326. Bibcode:2016NatSR...631326G. doi:10.1038/srep31326. PMC 4977546. PMID 27502179.

- Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Rohland N, Mallick S, Llamas B, et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Harrison, Richard J.; Heyd, Volker (20 December 2007). "The Transformation of Europe in the Third Millennium BC: the example of 'Le Petit-Chasseur I + III' (Sion, Valais, Switzerland)". Praehistorische Zeitschrift. 82 (2). De Gruyter: 129–214. doi:10.1515/PZ.2007.010. OCLC 718304072.

- Hermes, Taylor R.; et al. (1 December 2020). "Mitochondrial DNA of domesticated sheep confirms pastoralist component of Afanasievo subsistence economy in the Altai Mountains (3300-2900 cal BC)". Archaeological Research in Asia. 24 100232. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2020.100232. ISSN 2352-2267. S2CID 225136827.

- Jeong, Choongwon; et al. (29 April 2019). "The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia languages in Europe". Nature Ecology and Evolution. 3 (6). Nature Research: 966–976. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0878-2. hdl:10871/36562. PMC 6542712. PMID 31036896.

- Jones, Eppie R.; et al. (2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nature Communications. 6 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- Jones ER, Zarina G, Moiseyev V, Lightfoot E, Nigst PR, Manica A, Pinhasi R, Bradley DG (2017). "The Neolithic transition in the Baltic was not driven by admixture with early European farmers". Current Biology. 27 (4): 576–582. Bibcode:2017CBio...27..576J. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.060. PMC 5321670. PMID 28162894.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. bioRxiv 10.1101/059311. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Lazaridis I, Nadel D, Rollefson G, Merrett DC, Rohland N, Mallick S, et al. (25 July 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617) (published August 2016): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (26 August 2022). "A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia". Science. 377 (6609): 940–951. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..940L. doi:10.1126/science.abq0755. hdl:20.500.12684/12351. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 10019558. PMID 36007020. S2CID 251844202.

- Lazaridis, I.; et al. (5 February 2025). "The Genetic Origin of the Indo-Europeans" (PDF). Nature. 639 (Advance online publication). Nature Research: 132–142. Bibcode:2025Natur.639..132L. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-08531-5. PMC 11922553. PMID 39910300.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997), "Yamna Culture", Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn

- Mallory, J.P. (1999), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth (reprint ed.), London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7

- Martiniano, R, et al. (2017). "The population genomics of archaeological transition in west Iberia: Investigation of ancient substructure using imputation and haplotype-based methods". PLOS Genet. 13 (7) e1006852. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006852. PMC 5531429. PMID 28749934.

- Mathieson, Iain; et al. (10 October 2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv 10.1101/016477.

- Mathieson, Iain; et al. (23 November 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583) (published 24 December 2015): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Mathieson, Iain; et al. (21 February 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695). Nature Research: 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Morgunova, Nina; Khokhlova, Olga (2013). "Chronology and Periodization of the Pit-Grave Culture in the Area Between the Volga and Ural Rivers Based on 14C Dating and Paleopedological Research". Radiocarbon. 55 (2–3): 1286–1296. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16087. ISSN 0033-8222.

- Narasimhan VM, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Rohland N, et al. (2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457) eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Nikitin, Alexey G.; et al. (24 February 2017). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of eneolithic trypillians from Ukraine reveals neolithic farming genetic roots". PLOS ONE. 12 (2) e0172952. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1272952N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172952. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5325568. PMID 28235025.

- Nikitin, Alexey G.; et al. (2 February 2017). "Subdivisions of haplogroups U and C encompass mitochondrial DNA lineages of Eneolithic–Early Bronze Age Kurgan populations of western North Pontic steppe". Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (6): 605–613. doi:10.1038/jhg.2017.12. ISSN 1435-232X. PMID 28148921. S2CID 7459815.

- Nikitin, A. G.; et al. (5 February 2025). "A genomic history of the North Pontic Region from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age" (PDF). Nature. 639 (8053): 124–131. Bibcode:2025Natur.639..124N. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-08372-2. PMC 11909631. PMID 39910299.

- Nordgvist, Kerkko; Heyd, Volker (2020). "The Forgotten Child of the Wider Corded Ware Family: Russian Fatyanovo Culture in Context". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 86: 65–93. doi:10.1017/ppr.2020.9. S2CID 228923806.

- Novembre, John (11 June 2015). "Ancient DNA steps into the language debate". Nature. 522 (7555): 164–165. doi:10.1038/522164a. PMID 26062506. S2CID 205085294.

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism, Oxford University Press

- Pashnick, Jeff (August 2014). Genetic Analysis of Ancient Human Remains from the Early Bronze Age Cultures of the North PonticSteppe Region (Masters Theses thesis). Vol. 737. Grand Valley State University. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- Pathak AK, Kadian A, Kushniarevich A, Montinaro F, Mondal M, Ongaro L, et al. (6 December 2018). "The Genetic Ancestry of Modern Indus Valley Populations from Northwest India". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (6): 918–929. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.022. PMC 6288199. PMID 30526867.

- Saag, L.; Metspalu, M. (5 February 2025). "Genetic and geographical origins of Eurasia's influential Yamna culture". Nature. 639 (8053): 46–47. Bibcode:2025Natur.639...46S. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-00089-0. PMID 39910367.

- Shishlina, Natalia I. (11 May 2023). "Yamnaya Pastoralists in the Eurasian Desert Steppe Zone: New Perspectives on Mobility". In Kristiansen, Kristian; Kroonen, Guus; Willerslev, Eske (eds.). The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–41. doi:10.1017/9781009261753.006. ISBN 978-1-00-926175-3. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- Trautmann, Martin (2023). "First bioanthropological evidence for Yamnaya horsemanship". Science Advances. 9 (9) eade2451. Bibcode:2023SciA....9E2451T. doi:10.1126/sciadv.ade2451. hdl:10138/356326. PMC 10954216. PMID 36867690. S2CID 257334477.

- Unterländer, Martina; et al. (2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao; et al. (4 February 2019). "Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions Eurasia". Nature Communications. 10 (1). Nature Research: 590. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..590W. bioRxiv 10.1101/322347. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8. PMC 6360191. PMID 30713341.

- Wilde S, Timpson A, Kirsanow K, Kaiser E, Kayser M, Unterländer M, et al. (2014). "Direct evidence for positive selection of skin, hair, and eye pigmentation in Europeans during the last 5,000 y". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (13): 4832–4837. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4832W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316513111. PMC 3977302. PMID 24616518.

External links

[edit]- Spinney, Laura (5 May 2024). "Archaeologists identify the birthplace of the mysterious Yamnaya". The Economist.

- "Genetic study revives debate on origin and expansion of Indo-European Languages". Science Daily. March 2015.

- "First Horse Warriors". PBS.org NOVA series. 15 May 2019.

Yamnaya culture

View on GrokipediaThe Yamnaya culture, also known as the Yamna or Pit Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age nomadic pastoralist society that emerged on the Pontic–Caspian steppe north of the Black and Caspian Seas around 3300 BC and persisted until approximately 2600 BC.[1][2] It is defined archaeologically by the widespread construction of kurgans—earthen tumuli raised over simple pit graves containing flexed skeletons dusted with red ochre, often accompanied by bronze or copper weapons, tools, pottery, and remains of sacrificed livestock such as cattle, sheep, and horses.[3][4] Yamnaya people maintained a mobile economy centered on herding domesticated animals, supplemented by dairying practices evidenced in lipid residues on pottery, and they were among the earliest to exploit horses for transport and possibly riding, alongside the use of wheeled wagons for bulk mobility across the grasslands.[2][5][6] Ancient DNA analysis indicates that Yamnaya genomes derived primarily from a mixture of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and populations with Caucasus ancestry, forming a genetic profile that expanded rapidly westward into Europe—contributing up to 75% of Corded Ware ancestry—and eastward toward Central Asia, providing empirical support for migrations linked to the initial spread of Indo-European languages.[7][8][1]

![Cis-Ural Yamnaya artefacts and burials[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Yamna_2.png/250px-Yamna_2.png)