Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sintashta

View on WikipediaSintashta[a] is an archaeological site in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia. It is the remains of a fortified settlement dating to the Bronze Age, c. 2100–1800 BC,[1] and is the type site of the Sintashta culture. The site has been characterised as a "fortified metallurgical industrial center."[2]

Key Information

Archaeology

[edit]The Sintashta complex of archaeological sites includes the fortified settlement of Sintashta, the Large Sintashta Kurgan, the Sintashta burial ground, the Sintashta III Kurgan, and the Small Sintashta burial ground (without a kurgan). It was discovered in 1968 by an expedition from the Ural State University. Research and excavations were conducted by the Ural-Kazakhstan Archaeological Expedition under the direction of V. F. Gening and G. B. Zdanovich until 1986. Senior Ural-area archaeologists L. N. Koryakova, V. I. Stefanov, and N. B. Vinogradov also participated in the study of the Sintashta complex.

Location

[edit]Sintashta is situated in the steppe just east of the southern Ural Mountains. The site is named for the adjacent Sintashta River, a tributary to the Tobol. The shifting course of the river over time has destroyed half of the site, leaving behind thirty one of the approximately fifty or sixty houses in the settlement.[3]

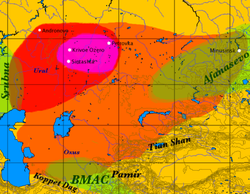

The better known settlement of Arkaim is about 30 kilometers from Sintashta. Arkaim is located along the Bolshaya Karaganka River, which is a tributary of Ural (river). From the source of the Sintashta River to the source of Bolshaya Karaganka River it's a straight line of 6 kilometers — across the watershed. There are several other ancient settlements in this same area, including the Bolshekaraganskiy kurgan. The Alakul settlement, which is the type site of the related Alakul culture is located to the northeast along the Miass (river), a tributary of the Tobol river.[4]

Description

[edit]The settlement consisted of rectangular houses arranged in a circle 140 m in diameter and surrounded by a timber-reinforced earthen wall with gate towers and a deep ditch on its exterior. The fortifications at Sintashta and similar settlements such as Arkaim were of unprecedented scale for the steppe region. There is evidence of copper and bronze metallurgy taking place in every house excavated at Sintashta, again an unprecedented intensity of metallurgical production for the steppe.[3] Early Abashevo culture ceramic styles strongly influenced Sintashta ceramics.[5] Due to the assimilation of tribes in the region of the Urals, such as the Pit-grave, Catacomb, Poltavka, and northern Abashevo into the Novokumak horizon, it would seem inaccurate to provide Sintashta with a purely Indo-Iranian attribution.[6] In the origin of Sintashta, the Abashevo culture would play an important role.[5]

Five cemeteries have been found associated with the site, the largest of which (known as Sintashta mogila or SM) consisted of forty graves. Some of these were chariot burials, producing the oldest known chariots in the world. Others included horse sacrifices—up to eight in a single grave—various stone, copper and bronze weapons, and silver and gold ornaments. The SM cemetery is overlain by a very large kurgan of a slightly later date. It has been suggested that the kind of funerary sacrifices evident at Sintashta have strong similarities to funerary rituals described in the Rig Veda.[3]

Radiocarbon dates from the settlement and cemeteries span over a millennium, suggesting an earlier occupation belonging to the Poltavka culture. The majority of the dates, however, are around 2100–1800 BC, which points at a main period of occupation of the site consistent with other settlements and cemeteries of the Sintashta culture.[3]

Sintashta II settlement

[edit]Based on four samples, the recent dating of Sintashta culture in Sintashta II settlement, (also known as Levobereznoe) is 2004-1852 calBC (2170-1900 calBC, 95.4% in the beginning of the sequence, and 1940-1660 calBC in the end).[7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ /sɪntɑːʃˈtɑː/; Russian: Синташта́, pronounced [sʲɪntɐˈʂta]

References

[edit]- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 374–375: "The radiocarbon dates for both the cemeteries and the settlement at Sintashta were worryingly diverse, from about 2800-2700 BCE (4200+ 100 BP), for wood from grave 11 in the SM cemetery, to about 1800-1600 BCE (3340+60BP), for wood from grave 5 in the SII cemetery. Probably there was an older Poltavka component at Sintashta, as later was found at many other sites of the Sintashta type, accounting for the older dates. Wood from the central grave of the large kurgan (SB) yielded consistent dates (3520+65, 3570+60, and 3720+120), or about 2100-1800 BCE".

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 371 : "And inside each and every house were the remains of metallurgical activity: slag, ovens, hearths, and copper. Sintashta was a fortified metallurgical industrial center".

- ^ a b c d Anthony 2007, pp. 371–375.

- ^ Location map of Bronze Age settlements in the Tobol river basin, including Sintashta, Arkaim and Alakul. Distribution of Sintashta (yellow circles) and Alakul (red circles) cultures sites. Source publication: Stanislav Grigoriev 2021, Andronovo Problem: Studies of Cultural Genesis in the Eurasian Bronze Age.

- ^ a b Anthony 2007, p. 382.

- ^ Elena E. Kuz'mina, The Origin of the Indo-Iranians, Volume 3, edited by J. P. Mallory, Brill NV, Leiden, 2007, p 222

- ^ Epimakhov, Zazovskaya & Alaeva 2023, p. 13: "Accordingly, the early 'Sintashta' phase is dated to 2004–1852 calBC. Its boundary events cover the intervals between 2170–1900 calBC at 95.4% at the beginning of the sequence and 1940–1660 calBC at 95.4% at the end".

Sources

[edit]- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Epimakhov, Andrey; Zazovskaya, Elya; Alaeva, Irina (August 7, 2023). "Migrations and Cultural Evolution in the Light of Radiocarbon Dating of Bronze Age Sites in the Southern Urals". Radiocarbon: 1–15. doi:10.1017/RDC.2023.62.

Further reading

[edit]- Генинг, В. Ф.; Зданович, Г. Б.; Генинг, В. В.; [V. F. Gening; G. B. Zdanovich; V. V. Gening] (1992). Синташта: археологические памятники арийских племен Урало-Казахстанских степей [Sintashta: archaeological sites of the Aryan tribes of the Ural-Kazakhstan Steppe] (in Russian). Chelyabinsk: Южно-Уральское книжное изд-во. ISBN 5-7688-0577-X.