Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Division by zero

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics, division by zero, division where the divisor (denominator) is zero, is a problematic special case. Using fraction notation, the general example can be written as , where is the dividend (numerator).

The usual definition of the quotient in elementary arithmetic is the number which yields the dividend when multiplied by the divisor. That is, is equivalent to . By this definition, the quotient is nonsensical, as the product is always rather than some other number . Following the ordinary rules of elementary algebra while allowing division by zero can create a mathematical fallacy, a subtle mistake leading to absurd results. To prevent this, the arithmetic of real numbers and more general numerical structures called fields leaves division by zero undefined, and situations where division by zero might occur must be treated with care. Since any number multiplied by zero is zero, the expression is also undefined.

Calculus studies the behavior of functions in the limit as their input tends to some value. When a real function can be expressed as a fraction whose denominator tends to zero, the output of the function becomes arbitrarily large, and is said to "tend to infinity", a type of mathematical singularity. For example, the reciprocal function, , tends to infinity as tends to . When both the numerator and the denominator tend to zero at the same input, the expression is said to take an indeterminate form, as the resulting limit depends on the specific functions forming the fraction and cannot be determined from their separate limits.

As an alternative to the common convention of working with fields such as the real numbers and leaving division by zero undefined, it is possible to define the result of division by zero in other ways, resulting in different number systems. For example, the quotient can be defined to equal zero; it can be defined to equal a new explicit point at infinity, sometimes denoted by the infinity symbol ; or it can be defined to result in signed infinity, with positive or negative sign depending on the sign of the dividend. In these number systems division by zero is no longer a special exception per se, but the point or points at infinity involve their own new types of exceptional behavior.

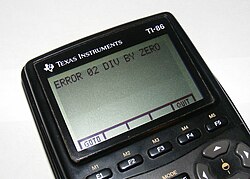

In computing, an error may result from an attempt to divide by zero. Depending on the context and the type of number involved, dividing by zero may evaluate to positive or negative infinity, return a special not-a-number value, or crash the program, among other possibilities.

Elementary arithmetic

[edit]The meaning of division

[edit]The division can be conceptually interpreted in several ways.[1]

In quotitive division, the dividend is imagined to be split up into parts of size (the divisor), and the quotient is the number of resulting parts. For example, imagine ten slices of bread are to be made into sandwiches, each requiring two slices of bread. A total of five sandwiches can be made (). Now imagine instead that zero slices of bread are required per sandwich (perhaps a lettuce wrap). Arbitrarily many such sandwiches can be made from ten slices of bread, as the bread is irrelevant.[2]

The quotitive concept of division lends itself to calculation by repeated subtraction: dividing entails counting how many times the divisor can be subtracted before the dividend runs out. Because no finite number of subtractions of zero will ever exhaust a non-zero dividend, calculating division by zero in this way never terminates.[3] Such an interminable division-by-zero algorithm is physically exhibited by some mechanical calculators.[4]

In partitive division, the dividend is imagined to be split into parts, and the quotient is the resulting size of each part. For example, imagine ten cookies are to be divided among two friends. Each friend will receive five cookies (). Now imagine instead that the ten cookies are to be divided among zero friends. How many cookies will each friend receive? Since there are no friends, this is an absurdity.[5]

In another interpretation, the quotient represents the ratio .[6] For example, a cake recipe might call for ten cups of flour and two cups of sugar, a ratio of or, proportionally, . To scale this recipe to larger or smaller quantities of cake, a ratio of flour to sugar proportional to could be maintained, for instance one cup of flour and one-fifth cup of sugar, or fifty cups of flour and ten cups of sugar.[7] Now imagine a sugar-free cake recipe calls for ten cups of flour and zero cups of sugar. The ratio , or proportionally , is perfectly sensible:[8] it just means that the cake has no sugar. However, the question "How many parts flour for each part sugar?" still has no meaningful numerical answer.

A geometrical appearance of the division-as-ratio interpretation is the slope of a straight line in the Cartesian plane.[9] The slope is defined to be the "rise" (change in vertical coordinate) divided by the "run" (change in horizontal coordinate) along the line. When this is written using the symmetrical ratio notation, a horizontal line has slope and a vertical line has slope . However, if the slope is taken to be a single real number then a horizontal line has slope while a vertical line has an undefined slope, since in real-number arithmetic the quotient is undefined.[10] The real-valued slope of a line through the origin is the vertical coordinate of the intersection between the line and a vertical line at horizontal coordinate , dashed black in the figure. The vertical red and dashed black lines are parallel, so they have no intersection in the plane. Sometimes they are said to intersect at a point at infinity, and the ratio is represented by a new number ;[11] see § Projectively extended real line below. Vertical lines are sometimes said to have an "infinitely steep" slope.

Inverse of multiplication

[edit]Division is the inverse of multiplication, meaning that multiplying and then dividing by the same non-zero quantity, or vice versa, leaves an original quantity unchanged; for example .[12] Thus a division problem such as can be solved by rewriting it as an equivalent equation involving multiplication, , where represents the same unknown quantity, and then finding the value for which the statement is true; in this case the unknown quantity is , because , so therefore .[13]

An analogous problem involving division by zero, , requires determining an unknown quantity satisfying . However, any number multiplied by zero is zero rather than six, so there exists no number which can substitute for to make a true statement.[14]

When the problem is changed to , the equivalent multiplicative statement is ; in this case any value can be substituted for the unknown quantity to yield a true statement, so there is no single number which can be assigned as the quotient .

Because of these difficulties, quotients where the divisor is zero are traditionally taken to be undefined, and division by zero is not allowed.[15][16]

Fallacies

[edit]A compelling reason for not allowing division by zero is that allowing it leads to fallacies.

When working with numbers, it is easy to identify an illegal division by zero. For example:

The fallacy here arises from the assumption that it is legitimate to cancel like any other number, whereas, in fact, doing so is a form of division by .

Using algebra, it is possible to disguise a division by zero[17] to obtain an invalid proof. For example:[18]

This is essentially the same fallacious computation as the previous numerical version, but the division by zero was obfuscated because we wrote as .

Early attempts

[edit]The Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta of Brahmagupta (c. 598–668) is the earliest text to treat zero as a number in its own right and to define operations involving zero.[17] According to Brahmagupta,

A positive or negative number when divided by zero is a fraction with the zero as denominator. Zero divided by a negative or positive number is either zero or is expressed as a fraction with zero as numerator and the finite quantity as denominator. Zero divided by zero is zero.

In 830, Mahāvīra unsuccessfully tried to correct the mistake Brahmagupta made in his book Ganita Sara Samgraha: "A number remains unchanged when divided by zero."[17]

Bhāskara II's Līlāvatī (12th century) proposed that division by zero results in an infinite quantity,[19]

A quantity divided by zero becomes a fraction the denominator of which is zero. This fraction is termed an infinite quantity. In this quantity consisting of that which has zero for its divisor, there is no alteration, though many may be inserted or extracted; as no change takes place in the infinite and immutable God when worlds are created or destroyed, though numerous orders of beings are absorbed or put forth.

Historically, one of the earliest recorded references to the mathematical impossibility of assigning a value to is contained in Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkeley's criticism of infinitesimal calculus in 1734 in The Analyst ("ghosts of departed quantities").[20]

Calculus

[edit]Calculus studies the behavior of functions using the concept of a limit, the value to which a function's output tends as its input tends to some specific value. The notation means that the value of the function can be made arbitrarily close to by choosing sufficiently close to .

In the case where the limit of the real function increases without bound as tends to , the function is not defined at , a type of mathematical singularity. Instead, the function is said to "tend to infinity", denoted , and its graph has the line as a vertical asymptote. While such a function is not formally defined for , and the infinity symbol in this case does not represent any specific real number, such limits are informally said to "equal infinity". If the value of the function decreases without bound, the function is said to "tend to negative infinity", . In some cases a function tends to two different values when tends to from above () and below (); such a function has two distinct one-sided limits.[21]

A basic example of an infinite singularity is the reciprocal function, , which tends to positive or negative infinity as tends to :

In most cases, the limit of a quotient of functions is equal to the quotient of the limits of each function separately,

However, when a function is constructed by dividing two functions whose separate limits are both equal to , then the limit of the result cannot be determined from the separate limits, so is said to take an indeterminate form, informally written . (Another indeterminate form, , results from dividing two functions whose limits both tend to infinity.) Such a limit may equal any real value, may tend to infinity, or may not converge at all, depending on the particular functions. For example, in the separate limits of the numerator and denominator are , so we have the indeterminate form , but simplifying the quotient first shows that the limit exists:

Alternative number systems

[edit]Extended real line

[edit]The affinely extended real numbers are obtained from the real numbers by adding two new numbers and , read as "positive infinity" and "negative infinity" respectively, and representing points at infinity. With the addition of , the concept of a "limit at infinity" can be made to work like a finite limit. When dealing with both positive and negative extended real numbers, the expression is usually left undefined. However, in contexts where only non-negative values are considered, it is often convenient to define .

Projectively extended real line

[edit]The set is the projectively extended real line, which is a one-point compactification of the real line. Here means an unsigned infinity or point at infinity, an infinite quantity that is neither positive nor negative. This quantity satisfies , which is necessary in this context. In this structure, can be defined for nonzero , and when is not . It is the natural way to view the range of the tangent function and cotangent functions of trigonometry: approaches the single point at infinity as approaches either or from either direction.

This definition leads to many interesting results. However, the resulting algebraic structure is not a field, and should not be expected to behave like one. For example, is undefined in this extension of the real line.

Riemann sphere

[edit]The subject of complex analysis applies the concepts of calculus in the complex numbers. Of major importance in this subject is the extended complex numbers , the set of complex numbers with a single additional number appended, usually denoted by the infinity symbol and representing a point at infinity, which is defined to be contained in every exterior domain, making those its topological neighborhoods.

This can intuitively be thought of as wrapping up the infinite edges of the complex plane and pinning them together at the single point , a one-point compactification, making the extended complex numbers topologically equivalent to a sphere. This equivalence can be extended to a metrical equivalence by mapping each complex number to a point on the sphere via inverse stereographic projection, with the resulting spherical distance applied as a new definition of distance between complex numbers; and in general the geometry of the sphere can be studied using complex arithmetic, and conversely complex arithmetic can be interpreted in terms of spherical geometry. As a consequence, the set of extended complex numbers is often called the Riemann sphere. The set is usually denoted by the symbol for the complex numbers decorated by an asterisk, overline, tilde, or circumflex, for example .

In the extended complex numbers, for any nonzero complex number , ordinary complex arithmetic is extended by the additional rules , , , , . However, , , and are left undefined.

Higher mathematics

[edit]The four basic operations – addition, subtraction, multiplication and division – as applied to whole numbers (positive integers), with some restrictions, in elementary arithmetic are used as a framework to support the extension of the realm of numbers to which they apply. For instance, to make it possible to subtract any whole number from another, the realm of numbers must be expanded to the entire set of integers in order to incorporate the negative integers. Similarly, to support division of any integer by any other, the realm of numbers must expand to the rational numbers. During this gradual expansion of the number system, care is taken to ensure that the "extended operations", when applied to the older numbers, do not produce different results. Loosely speaking, since division by zero has no meaning (is undefined) in the whole number setting, this remains true as the setting expands to the real or even complex numbers.[22]

As the realm of numbers to which these operations can be applied expands there are also changes in how the operations are viewed. For instance, in the realm of integers, subtraction is no longer considered a basic operation since it can be replaced by addition of signed numbers.[23] Similarly, when the realm of numbers expands to include the rational numbers, division is replaced by multiplication by certain rational numbers. In keeping with this change of viewpoint, the question, "Why can't we divide by zero?", becomes "Why can't a rational number have a zero denominator?". Answering this revised question precisely requires close examination of the definition of rational numbers.

In the modern approach to constructing the field of real numbers, the rational numbers appear as an intermediate step in the development that is founded on set theory. First, the natural numbers (including zero) are established on an axiomatic basis such as Peano's axiom system and then this is expanded to the ring of integers. The next step is to define the rational numbers keeping in mind that this must be done using only the sets and operations that have already been established, namely, addition, multiplication and the integers. Starting with the set of ordered pairs of integers, with , define a binary relation on this set by if and only if . This relation is shown to be an equivalence relation and its equivalence classes are then defined to be the rational numbers. It is in the formal proof that this relation is an equivalence relation that the requirement that the second coordinate is not zero is needed (for verifying transitivity).[24][25][26]

Although division by zero cannot be sensibly defined with real numbers and integers, it is possible to consistently define it, or similar operations, in other mathematical structures.

Non-standard analysis

[edit]In the hyperreal numbers, division by zero is still impossible, but division by non-zero infinitesimals is possible.[27] The same holds true in the surreal numbers.[28]

Distribution theory

[edit]In distribution theory one can extend the function to a distribution on the whole space of real numbers (in effect by using Cauchy principal values). It does not, however, make sense to ask for a "value" of this distribution at ; a sophisticated answer refers to the singular support of the distribution.

Linear algebra

[edit]In matrix algebra, square or rectangular blocks of numbers are manipulated as though they were numbers themselves: matrices can be added and multiplied, and in some cases, a version of division also exists. Dividing by a matrix means, more precisely, multiplying by its inverse. Not all matrices have inverses.[29] For example, a matrix containing only zeros is not invertible.

One can define a pseudo-division, by setting , in which represents the pseudoinverse of . It can be proven that if exists, then . If , then .

Abstract algebra

[edit]In abstract algebra, the integers, the rational numbers, the real numbers, and the complex numbers can be abstracted to more general algebraic structures, such as a commutative ring, which is a mathematical structure where addition, subtraction, and multiplication behave as they do in the more familiar number systems, but division may not be defined. Adjoining a multiplicative inverses to a commutative ring is called localization. However, the localization of every commutative ring at zero is the trivial ring, where , so nontrivial commutative rings do not have inverses at zero, and thus division by zero is undefined for nontrivial commutative rings.

Nevertheless, any number system that forms a commutative ring can be extended to a structure called a wheel in which division by zero is always possible.[30] However, the resulting mathematical structure is no longer a commutative ring, as multiplication no longer distributes over addition. Furthermore, in a wheel, division of an element by itself no longer results in the multiplicative identity element , and if the original system was an integral domain, the multiplication in the wheel no longer results in a cancellative semigroup.

The concepts applied to standard arithmetic are similar to those in more general algebraic structures, such as rings and fields. In a field, every nonzero element is invertible under multiplication; as above, division poses problems only when attempting to divide by zero. This is likewise true in a skew field (which for this reason is called a division ring). However, in other rings, division by nonzero elements may also pose problems. For example, the ring of integers modulo 6. The meaning of the expression should be the solution of the equation . But in the ring , is a zero divisor. This equation has two distinct solutions, and , so the expression is undefined.

In field theory, the expression is only shorthand for the formal expression , where is the multiplicative inverse of . Since the field axioms only guarantee the existence of such inverses for nonzero elements, this expression has no meaning when is zero. Modern texts, which define fields as a special type of ring, include the axiom for fields (or its equivalent) so that the zero ring is excluded from being a field. In the zero ring, division by zero is possible, which shows that the other field axioms alone are not sufficient to exclude division by zero in defining a field.

Computer arithmetic

[edit]Floating-point arithmetic

[edit]In computing, most numerical calculations are done with floating-point arithmetic, which since the 1980s has been standardized by the IEEE 754 specification. In IEEE floating-point arithmetic, numbers are represented using a sign (positive or negative), a fixed-precision significand and an integer exponent. Numbers whose exponent is too large to represent instead "overflow" to positive or negative infinity (+∞ or −∞), while numbers whose exponent is too small to represent instead "underflow" to positive or negative zero (+0 or −0). A NaN (not a number) value represents undefined results.

In IEEE arithmetic, division of 0/0 or ∞/∞ results in NaN, but otherwise division always produces a well-defined result. Dividing any non-zero number by positive zero (+0) results in an infinity of the same sign as the dividend. Dividing any non-zero number by negative zero (−0) results in an infinity of the opposite sign as the dividend. This definition preserves the sign of the result in case of arithmetic underflow.[31]

For example, using single-precision IEEE arithmetic, if , then underflows to , and dividing by this result produces . The exact result is too large to represent as a single-precision number, so an infinity of the same sign is used instead to indicate overflow.

Integer arithmetic

[edit]

Integer division by zero is usually handled differently from floating point since there is no integer representation for the result. CPUs differ in behavior: for instance x86 processors trigger a hardware exception, while PowerPC processors silently generate an incorrect result for the division and continue, and ARM processors can either cause a hardware exception or return zero.[32] Because of this inconsistency between platforms, the C and C++ programming languages consider the result of dividing by zero undefined behavior.[33] In typical higher-level programming languages, such as Python,[34] an exception is raised for attempted division by zero, which can be handled in another part of the program.

In proof assistants

[edit]Many proof assistants, such as Rocq and Lean, define 1/0 = 0. This is due to the requirement that all functions are total. Such a definition does not create contradictions, as further manipulations (such as cancelling out) still require that the divisor is non-zero.[35][36]

Historical accidents

[edit]- On 21 September 1997, a division by zero error in the "Remote Data Base Manager" aboard USS Yorktown (CG-48) brought down all the machines on the network, causing the ship's propulsion system to fail.[37][38]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Cheng 2023, pp. 75–83.

- ^ Zazkis & Liljedahl 2009, p. 52–53.

- ^ Zazkis & Liljedahl 2009, p. 55–56.

- ^ Kochenburger, Ralph J.; Turcio, Carolyn J. (1974), Computers in Modern Society, Santa Barbara: Hamilton,

Some other operations, including division, can also be performed by the desk calculator (but don't try to divide by zero; the calculator never will stop trying to divide until stopped manually).

For a video demonstration, see: What happens when you divide by zero on a mechanical calculator?, 7 Mar 2021, retrieved 2024-01-06 – via YouTube - ^ Zazkis & Liljedahl 2009, pp. 53–54, gives an example of a king's heirs equally dividing their inheritance of 12 diamonds, and asks what would happen in the case that all of the heirs died before the king's will could be executed.

- ^ In China, Taiwan, and Japan, school textbooks typically distinguish between the ratio and the value of the ratio . By contrast in the USA textbooks typically treat them as two notations for the same thing. Lo, Jane-Jane; Watanabe, Tad; Cai, Jinfa (2004), "Developing Ratio Concepts: An Asian Perspective", Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 9 (7): 362–367, doi:10.5951/MTMS.9.7.0362, JSTOR 41181943

- ^ Cengiz, Nesrin; Rathouz, Margaret (2018), "Making Sense of Equivalent Ratios", Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 24 (3): 148–155, doi:10.5951/mathteacmiddscho.24.3.0148, JSTOR 10.5951/mathteacmiddscho.24.3.0148, S2CID 188092067

- ^ Clark, Matthew R.; Berenson, Sarah B.; Cavey, Laurie O. (2003), "A comparison of ratios and fractions and their roles as tools in proportional reasoning", The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 22 (3): 297–317, doi:10.1016/S0732-3123(03)00023-3

- ^ Cheng, Ivan (2010), "Fractions: A New Slant on Slope", Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 16 (1): 34–41, doi:10.5951/MTMS.16.1.0034, JSTOR 41183440

- ^ Cavey, Laurie O.; Mahavier, W. Ted (2010), "Seeing the potential in students' questions", The Mathematics Teacher, 104 (2): 133–137, doi:10.5951/MT.104.2.0133, JSTOR 20876802

- ^ Wegman, Edward J.; Said, Yasmin H. (2010), "Natural homogeneous coordinates", Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 2 (6): 678–685, doi:10.1002/wics.122, S2CID 121947341

- ^ Robinson, K. M.; LeFevre, J. A. (2012), "The inverse relation between multiplication and division: Concepts, procedures, and a cognitive framework", Educational Studies in Mathematics, 79 (3): 409–428, doi:10.1007/s10649-011-9330-5, JSTOR 41413121

- ^ Cheng 2023, p. 78; Zazkis & Liljedahl 2009, p. 55

- ^ Zazkis & Liljedahl 2009, p. 55.

- ^ Cheng 2023, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Bunch 1982, p. 14

- ^ a b c Kaplan, Robert (1999), The Nothing That Is: A Natural History of Zero, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 68–75, ISBN 978-0-19-514237-2

- ^ Bunch 1982, p. 15

- ^ Roy, Rahul (Jan 2003), "Babylonian Pythagoras' Theorem, the Early History of Zero and a Polemic on the Study of the History of Science", Resonance, 8 (1): 30–40, doi:10.1007/BF02834448

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1929), "Absurdities due to division by zero: An historical note", The Mathematics Teacher, 22 (6): 366–368, doi:10.5951/MT.22.6.0366, JSTOR 27951153.

- ^ Herman, Edwin; Strang, Gilbert; et al. (2023), "2.2 The Limit of a Function", Calculus, vol. 1, Houston: OpenStax, p. 454, ISBN 978-1-947172-13-5, OCLC 1022848630

- ^ Klein 1925, p. 63

- ^ Klein 1925, p. 26

- ^ Schumacher 1996, p. 149

- ^ Hamilton 1982, p. 19

- ^ Henkin et al. 2012, p. 292

- ^ Keisler, H. Jerome (2023) [1986], Elementary Calculus: An Infinitesimal Approach, Prindle, Weber & Schmidt, pp. 29–30

- ^ Conway, John H. (2000) [1976], On Numbers and Games (2nd ed.), CRC Press, p. 20, ISBN 9781568811277

- ^ Gbur, Greg (2011), Mathematical Methods for Optical Physics and Engineering, Cambridge University Press, pp. 88–93, Bibcode:2011mmop.book.....G, ISBN 978-0-521-51610-5

- ^ Carlström, Jesper (2004), "Wheels: On Division by Zero", Mathematical Structures in Computer Science, 14 (1): 143–184, doi:10.1017/S0960129503004110

- ^ Cody, W. J. (Mar 1981), "Analysis of Proposals for the Floating-Point Standard", Computer, 14 (3): 65, doi:10.1109/C-M.1981.220379, S2CID 9923085,

With appropriate care to be certain that the algebraic signs are not determined by rounding error, the affine mode preserves order relations while fixing up overflow. Thus, for example, the reciprocal of a negative number which underflows is still negative.

- ^ "Divide instructions", ARMv7-M Architecture Reference Manual (Version D ed.), Arm Limited, 2010, retrieved 2024-06-12

- ^ Wang, Xi; Chen, Haogang; Cheung, Alvin; Jia, Zhihao; Zeldovich, Nickolai; Kaashoek, M. Frans, "Undefined behavior: what happened to my code?", APSYS '12: Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Workshop on Systems, APSYS '12, Seoul, 23–24 July 2012, New York: Association for Computing Machinery, doi:10.1145/2349896.2349905, hdl:1721.1/86949, ISBN 978-1-4503-1669-9

- ^ "Built-in Exceptions", Python 3 Library Reference, Python Software Foundation, § "Concrete exceptions – exception

ZeroDivisionError", retrieved 2024-01-22 - ^ Tanter, Éric; Tabareau, Nicolas (2015), "Gradual certified programming in coq", DLS 2015: Proceedings of the 11th Symposium on Dynamic Languages, Association for Computing Machinery, arXiv:1506.04205, doi:10.1145/2816707.2816710,

The standard division function on natural numbers in Coq, div, is total and pure, but incorrect: when the divisor is 0, the result is 0.

- ^ Buzzard, Kevin (5 Jul 2020), "Division by zero in type theory: a FAQ", Xena Project (Blog), retrieved 2024-01-21

- ^ Stutz, Michael (24 Jul 1998), "Sunk by Windows NT", Wired News, archived from the original on 1999-04-29

- ^ William Kahan (14 Oct 2011), Desperately Needed Remedies for the Undebuggability of Large Floating-Point Computations in Science and Engineering (PDF)

Sources

[edit]- Bunch, Bryan (1982), Mathematical Fallacies and Paradoxes, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 0-442-24905-5 (Dover reprint 1997)

- Cheng, Eugenia (2023), Is Math(s) Real? How Simple Questions Lead Us to Mathematics' Deepest Truths, Basic Books, ISBN 978-1-541-60182-6

- Klein, Felix (1925), Elementary Mathematics from an Advanced Standpoint / Arithmetic, Algebra, Analysis, translated by Hedrick, E. R.; Noble, C. A. (3rd ed.), Dover

- Hamilton, A. G. (1982), Numbers, Sets, and Axioms, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521287616

- Henkin, Leon; Smith, Norman; Varineau, Verne J.; Walsh, Michael J. (2012), Retracing Elementary Mathematics, Literary Licensing LLC, ISBN 978-1258291488

- Schumacher, Carol (1996), Chapter Zero : Fundamental Notions of Abstract Mathematics, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-82653-1

- Zazkis, Rina; Liljedahl, Peter (2009), "Stories that explain", Teaching Mathematics as Storytelling, Sense Publishers, pp. 51–65, doi:10.1163/9789087907358_008, ISBN 978-90-8790-734-1

Further reading

[edit]- Northrop, Eugene P. (1944), Riddles in Mathematics: A Book of Paradoxes, New York: D. Van Nostrand, Ch. 5 "Thou Shalt Not Divide By Zero", pp. 77–96

- Seife, Charles (2000), Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, New York: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-029647-6

- Suppes, Patrick (1957), Introduction to Logic, Princeton: D. Van Nostrand, §8.5 "The Problem of Division by Zero" and §8.7 "Five Approaches to Division by Zero" (Dover reprint, 1999)

- Tarski, Alfred (1941), Introduction to Logic and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences, Oxford University Press, §53 "Definitions whose definiendum contains the identity sign"

Division by zero

View on GrokipediaFundamentals in Arithmetic

Interpretation of Division

In elementary arithmetic, division is fundamentally interpreted as a process of partitioning a quantity into equal parts or measuring how many times one quantity fits into another. For instance, the expression seeks to determine the number of groups of size that can be formed from (partitive or partitioning model) or the number of units of that fit into (quotative or measurement model).[6][7] This intuitive understanding underpins division as a practical operation for sharing or scaling quantities in everyday contexts. Formally, division serves as a binary operation on the set of real numbers, defined for any dividend and divisor where . It produces a unique quotient that satisfies the relation , ensuring consistency within the arithmetic structure.[8] However, when the divisor is zero, this operation fails to yield a meaningful result. Dividing by 0 would require identifying a quotient such that , but multiplication by zero always yields 0 regardless of , making the equation impossible to satisfy for any nonzero .[1][9] Consider the specific case of : no real number exists that fulfills , as the right side remains 0 for all . This inconsistency renders division by zero undefined in the real numbers, preserving the integrity of arithmetic operations.[9] In ancient mathematical traditions, such as those of the Greeks and Romans, the absence of zero as a numeral meant that division by zero was not explicitly addressed, with calculations relying on non-positional systems that avoided such scenarios.[10] This partitioning perspective connects to division's role as the multiplicative inverse, though its algebraic properties are examined in greater detail elsewhere.As Inverse of Multiplication

In standard arithmetic, division is defined as the operation of multiplying by the multiplicative inverse. Specifically, for real numbers and where , the quotient equals , with denoting the reciprocal of , which is the unique real number satisfying .[11] The element zero lacks a multiplicative inverse in the real numbers because no real number exists such that ; instead, holds for every real .[12] This absence follows directly from the properties of multiplication by zero, rendering the reciprocal of zero undefined.[13] Attempting to define for leads to an algebraic contradiction. Suppose for some real ; then, by the definition of division, , which contradicts the assumption that .[2] Similarly, defining an inverse for zero, say , implies , yielding the absurdity .[1] This issue aligns with the structure of the real numbers as a field, where the axioms require that every non-zero element possesses a unique multiplicative inverse, but explicitly exclude zero from this property to maintain consistency.[14] In such fields, the multiplicative group consists solely of non-zero elements, ensuring that division remains well-defined only when the divisor is non-zero.[15]Common Fallacies

One common fallacy arises when attempting to manipulate equations by dividing both sides by zero, leading to absurd conclusions like 1 = 2. Consider the following steps: assume , then multiply both sides by to get ; subtract from both sides to obtain ; factor the left side as and the right as , yielding ; now "divide" both sides by to arrive at ; substituting gives , and dividing by (assuming ) results in 2 = 1.[2] This "proof" fails because the division by is invalid, as division by zero is undefined.[2] A related error occurs in algebraic manipulations where an expression that can equal zero is divided out without considering special cases. For instance, start with the equation , which correctly implies or . "Dividing" both sides by yields 1 = 0, a contradiction.[16] The mistake lies in ignoring that at the solutions and , making the division step undefined for those values.[16] Such improper cancellation of terms is a frequent pedagogical example in algebra, emphasizing the need to check for zero divisors before simplifying.[16] Another fallacy involves treating as infinity, then deriving inconsistencies. Suppose ; multiplying both sides by 0 gives . However, infinity is not a real number, and is indeterminate, leading to contradictions like equating it to any value.[9] This error stems from conflating limits (where expressions approach infinity as the denominator nears zero) with actual division in the real numbers.[9] These fallacies occur because the division property of equality—if and , then —explicitly requires a nonzero divisor to preserve equivalence.[17] When , no real number satisfies for , violating the inverse nature of division and breaking the field's structure.[1] In basic arithmetic, this failure underscores why division by zero is undefined, preventing inconsistencies across the real numbers.[1]Historical Context

Early Mathematical Attempts

In ancient Greek mathematics, particularly in Euclid's Elements (circa 300 BCE), the concept of zero was absent from the number system, which focused on positive magnitudes and ratios in geometry. This absence inherently sidestepped issues of division by zero, as Euclid's propositions avoided scenarios where a divisor would be null, such as in constructions involving parallel lines or proportions where equality to zero was not contemplated.[18] Indian mathematics advanced the treatment of zero significantly in the 7th century CE with Brahmagupta's Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta (628 CE), the first text to systematically define arithmetic operations involving zero as a number. Brahmagupta provided rules such as: zero added to or subtracted from a number leaves it unchanged; a number multiplied by zero yields zero; and the sum of zero and zero is zero. For division, he stipulated that a positive or negative number divided by zero results in a fraction with zero in the denominator, interpreted as respective infinity, while zero divided by zero equals zero—a claim later recognized as inconsistent.[19] The exact rule states: "A positive [number] or a negative [number] divided by zero is [a fraction] with [zero] denominator," and "Zero divided by zero is [zero]."[19] In the 9th century, the Jain mathematician Mahāvīra in his Ganita Sara Samgraha (c. 850 CE) proposed that division of any non-zero number by zero leaves the number unchanged, treating it as an operation that yields the dividend itself. In the 12th century, Bhāskara II critiqued and refined Brahmagupta's approach in his Līlāvatī (1150 CE), addressing the anomalies in zero division more explicitly. He asserted that "a quantity divided by zero is a quantity denoted by infinity," introducing the concept of infinity and emphasizing its immutable nature, likening it to the eternal divine. Bhāskara noted: "A quantity divided by zero becomes a fraction the denominator of which is zero. This fraction is termed an infinite quantity. In this quantity consisting of that which has zero for its divisor, there is no alteration, though many may be inserted or extracted."[20] This marked an early conceptual link between division by zero and boundless quantity, though without rigorous limits. Islamic scholars in the 9th century, building on Indian numeral systems, treated zero cautiously in algebraic contexts to prevent undefined operations. Al-Khwārizmī, in his Al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala (circa 820 CE), incorporated zero as a placeholder in the Hindu-Arabic system but explicitly avoided zero coefficients and divisions by zero in solving equations, restricting cases to positive roots and non-null divisors to maintain computational integrity.[21] This algorithmic approach ensured practical avoidance while advancing systematic algebra.Notable Incidents and Anecdotes

One notable incident involving division by zero occurred on September 21, 1997, aboard the U.S. Navy guided-missile cruiser USS Yorktown (CG-48), part of the Navy's Smart Ship program. A crew member entered a zero value into a database field for a propulsion system parameter, which the software then used in a calculation, resulting in a division by zero error. This caused the entire network of shipboard computers to crash, disabling the propulsion, steering, and other engineering systems, leaving the ship adrift off the coast of Virginia for approximately 2.5 hours until manual reboot and recovery efforts restored functionality. The event highlighted the risks of unhandled exceptions in integrated computer systems and led to reviews of software robustness in naval applications.[22][23] In programming communities, a 2006 claim by a University of Reading professor garnered attention as a purported hoax or publicity stunt, asserting a solution to the 0/0 indeterminate form after 1,200 years. The paper suggested redefining arithmetic operations to allow division by zero without contradiction, but it was widely dismissed by mathematicians as flawed or satirical, sparking online discussions and media coverage about the enduring allure of "solving" this impossibility.[24][25] Cultural references often use division by zero for humor to emphasize computational absurdity. In a 2006 blog post, webcomic artist Randall Munroe of xkcd critiqued a similar professorial claim, joking that permitting division by zero would trivialize mathematics and lead to nonsensical results, such as proving all numbers equal; he quipped that it "makes the universe a little less interesting." This anecdote illustrates how the concept permeates popular science discourse as a symbol of logical breakdown.[26] In the 17th century, English mathematician John Wallis navigated issues related to zero in his development of the infinite product formula for π/2 in Arithmetica Infinitorum (1656), carefully structuring the product ∏_{n=1}^∞ [ (2n)/(2n-1) · (2n)/(2n+1) ] to converge without encountering direct division by zero, though he elsewhere treated 1/0 as infinity in discussions of limits and infinitesimals. Later, in 1770, Leonhard Euler reinforced this infinity interpretation in his algebraic works, further linking it to emerging concepts of limits. This approach avoided fallacious manipulations while advancing interpolation techniques, serving as an early anecdote of prudent handling in infinite expressions.[27]Real Analysis and Calculus

Limits Approaching Division by Zero

In calculus, limits offer a way to analyze expressions that would otherwise involve direct division by zero, which remains undefined in the real numbers. By evaluating the behavior of a quotient f(x)/g(x) as x approaches a point c where g(c) = 0, one can determine if a meaningful value emerges without substituting c directly. For example, the limit may exist and be finite even though is undefined, particularly when f(0) = 0, leading to the indeterminate form 0/0. This approach circumvents the arithmetic prohibition while capturing the function's tendency near the singularity.[28] A fundamental illustration involves the function 1/x as x approaches 0. The one-sided limits reveal divergent behaviors: from the right and from the left. Because these one-sided limits do not agree, the two-sided limit does not exist in the real numbers.[29][30] This divergence generalizes to nonzero constants: for any , approaches if x approaches from the positive side and from the negative side, again resulting in a nonexistent two-sided limit. In contrast, indeterminate forms such as 0/0 or often yield finite limits through techniques like L'Hôpital's rule, which equates under appropriate conditions, provided the latter limit exists. Formulated by Johann Bernoulli and published by Guillaume de l'Hôpital in 1696, this rule transforms problematic quotients into differentiable ones.[29]/04%3A_Applications_of_Derivatives/4.08%3A_LHopitals_Rule) A prominent example of resolving 0/0 is . Substituting x = 0 produces the indeterminate form, but L'Hôpital's rule gives . This result, foundational in trigonometry and analysis, can also be established via the squeeze theorem, bounding between linear tangents to confirm the limit's value. Such limits underscore how approaching division by zero can reveal precise behaviors otherwise obscured.[31][32] Limits approaching division by zero are integral to the derivative's definition, , where the denominator h tends to zero. This formulation, known as the difference quotient, evaluates the instantaneous rate of change without encountering division by exactly zero, enabling derivatives for a wide class of functions in real analysis.[33]Extended Real Line

The extended real line, denoted , is constructed by adjoining two infinite elements, and , to the set of real numbers , yielding . This extension preserves the natural order of the reals by defining for all , with as the greatest element and as the least. Arithmetic operations are extended via specific conventions to maintain consistency where possible: for any real , , if is finite; multiplication follows sign rules, such as if , if , and left undefined as indeterminate; division by nonzero reals remains standard, but direct division by zero is undefined in .[34][35] Although is totally ordered and complete in the sense of Dedekind cuts extended appropriately, it does not form a field due to the absence of multiplicative inverses for zero and infinities, and the presence of indeterminate forms like , , and . These indeterminate expressions arise because no unique value satisfies the operation consistently across all contexts. However, the structure proves valuable in real analysis for formalizing monotonic limits, where approaching division by zero from one side yields a definite infinite value: for , and , effectively assigning directional infinities to such divisions without defining outright. This builds on limit behaviors by embedding infinity as an actual element rather than a mere symbolic endpoint.[36] In applications to real analysis, the extended real line simplifies the treatment of improper integrals and asymptotic behaviors. For example, the improper integral is evaluated as , indicating divergence to positive infinity. Such evaluations are crucial for assessing convergence in series, functions with singularities, and monotonic sequences.[37] Despite these utilities, has limitations in handling certain indeterminate forms directly, such as or , which require additional techniques like L'Hôpital's rule or algebraic manipulation rather than the structure alone. Division involving zero remains undefined, preserving the integrity of the real arithmetic while extending its expressive power for limit-based contexts.Projective Extensions and Riemann Sphere

In projective geometry, the real projective line extends the real line by incorporating a point at infinity, unifying the behavior of division by zero through homogeneous coordinates , where points are equivalence classes under nonzero scalar multiplication.[38] These coordinates represent affine points as for finite , while for corresponds to the single point at infinity , identifying positive and negative infinities since .[39] Thus, the operation of division , undefined in the reals when , is resolved by mapping to , allowing consistent definitions such as and .[38] This structure provides a compactification of the real line into a circle topologically, where arithmetic operations like inversion are well-behaved at infinity, avoiding the directional distinctions of the extended real line.[38] For instance, approaching infinity from positive or negative directions yields the same point, ensuring as without sign ambiguity. The Riemann sphere extends this idea to the complex plane, forming the complex projective line by adjoining a single point at infinity to , visualized via stereographic projection from a unit sphere centered at the origin.[40] In this projection, the south pole maps to the origin in the complex plane (the equatorial plane ), while the north pole projects to .[41] Homogeneous coordinates over parallel the real case, with finite points as and as ; division is undefined at but represented by the point .[38] Arithmetic on the Riemann sphere incorporates such that limits like as and hold continuously, with inversion mapping to and vice versa, endowing the extended complexes with a structure where such operations are defined except for indeterminate forms like .[40] This makes the Riemann sphere a Riemann surface on which the extended complex numbers support a topological field-like behavior for rational operations. In complex analysis, the Riemann sphere is fundamental for studying meromorphic functions, which are holomorphic except at poles; for example, a function with a pole at zero, such as , acquires a zero at on the sphere, balancing the divisor .[42] All meromorphic functions on the Riemann sphere are rational functions with coprime polynomials and , where poles at zero correspond to zeros of and extend naturally to behavior at .[42] This framework resolves singularities like division by zero by relocating them to , enabling global analysis of residues and the argument principle.[41]Advanced Mathematical Structures

Non-Standard Analysis

Non-standard analysis, developed by Abraham Robinson in the 1960s, provides a rigorous framework for incorporating infinitesimal and infinite quantities into the real numbers through the construction of the hyperreal numbers *ℝ. The hyperreal numbers extend the standard real numbers ℝ by including non-zero infinitesimals ε, which are positive hyperreals smaller than every positive real number, as well as their reciprocals, which are infinite hyperreals larger than every real number.[43] This extension allows for exact arithmetic operations that approximate classical limits without directly dividing by zero. In the hyperreals, division by a non-zero infinitesimal is well-defined and yields an infinite hyperreal. For example, the reciprocal of an infinitesimal ε is 1/ε, which is an infinite hyperreal whose standard part is +∞ if ε > 0.[43] More generally, for a standard real number a ≠ 0, the expression a / ε, where ε ≈ 0 is a positive infinitesimal, results in a positive infinite hyperreal approximately equal to +∞ in the sense that its standard part is infinite. However, direct division by the standard zero remains undefined in *ℝ, as zero has no multiplicative inverse, preserving the algebraic structure of a field. Near-zero infinitesimals thus enable approximations to expressions involving division by zero, such as in limits, where classical approaches require approaching zero without reaching it. The transfer principle is a key feature of non-standard analysis, stating that any first-order logical statement true in the reals holds in the hyperreals when restricted to standard elements, and vice versa. This principle extends standard theorems to the hyperreal setting, allowing proofs to avoid explicit division by zero by instead operating with infinitesimals; for instance, derivatives can be defined as f'(x) = st((f(x + ε) - f(x))/ε), where st denotes the standard part function, yielding a real number without encountering exact zero in the denominator.[43] Robinson's framework thus reinterprets division by zero scenarios through infinitesimal approximations, providing conceptual clarity while maintaining mathematical rigor.Distribution Theory

In distribution theory, distributions are defined as continuous linear functionals on the space of test functions, typically the Schwartz space of smooth functions that decay rapidly at infinity along with all their derivatives.[44] This framework, pioneered by Laurent Schwartz in the 1950s, extends classical functions to handle singularities and allows for a rigorous treatment of generalized derivatives.[45] Division by zero is addressed through the principal value distribution , which regularizes the singularity at by defining its action on a test function (smooth functions with compact support) as [46] This limit exists because the symmetric exclusion around zero cancels the divergent parts, yielding a well-defined distribution.[47] Notably, the distributional derivative of equals , providing a way to interpret as the derivative of a locally integrable function while avoiding the point singularity at zero: [47] For higher-order singularities, such as those arising in for , the Hadamard finite part regularization extends this approach by subtracting divergent terms from the integral to extract the finite remainder, defining distributions like the finite part .[48] This technique, originally developed by Jacques Hadamard and integrated into distribution theory, handles non-integrable singularities systematically.[49] In applications to partial differential equations (PDEs) and Fourier analysis, these regularizations enable solutions to problems with zero denominators, such as finding fundamental solutions via convolution with the Dirac delta , for instance, in the Sokhotski–Plemelj theorem, .[50] In elliptic PDEs like the Poisson equation, logarithmic potentials involving lead to principal value terms that resolve singularities at sources.[51]Linear Algebra Applications

In linear algebra, division by zero manifests prominently in the context of matrix invertibility. A square matrix is singular if its determinant is zero, , which implies that has no inverse, analogous to dividing by zero in scalar arithmetic. This singularity arises because the linear transformation represented by is not bijective, collapsing the dimension of the space it maps onto.[52][53] Consider the linear system , where is an matrix and is a vector in . If , the system lacks a unique solution; instead, it has either no solution or infinitely many solutions, depending on whether lies in the column space of . Solutions exist if and only if is a linear combination of the columns of , ensuring consistency of the system despite the rank deficiency.[54][55][56] To address such ill-posed systems, the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse provides a generalized inverse, particularly useful for least-squares approximations. Defined for any matrix (singular or rectangular), satisfies the conditions , , , and , enabling solutions that minimize the Euclidean norm when no exact solution exists. This pseudoinverse, originally formulated by E. H. Moore in 1920 and R. Penrose in 1955, is computed via singular value decomposition, where zero singular values correspond to the kernel of .[57][58] In applications like least-squares regression, overdetermined systems () often encounter effective division by zero when the design matrix is rank-deficient. Here, yields the solution , projecting onto the column space of to find the best linear fit, as in minimizing residuals for data fitting without assuming full rank. Rank deficiency in is equivalently indicated by zero eigenvalues in its eigendecomposition, confirming non-invertibility since the determinant, the product of eigenvalues, vanishes.[59][60][61][62][63]Abstract Algebra Perspectives

In abstract algebra, rings provide a foundational structure for understanding multiplication and division, but they differ fundamentally from fields in their treatment of zero. A ring is an algebraic structure equipped with addition and multiplication operations satisfying certain axioms, such as distributivity, but not necessarily multiplicative inverses for all elements. In contrast, fields are commutative rings with unity where every non-zero element has a multiplicative inverse, allowing division by any non-zero element. In general rings, such as the integers , zero lacks a multiplicative inverse because there is no element satisfying , rendering division by zero undefined.[64] Rings may also contain zero divisors—non-zero elements and such that —which further complicate division, as multiplying by a zero divisor can lead to loss of information without a unique quotient.[64] Quotient rings, constructed by factoring out an ideal, exemplify rings with zero divisors where division by zero remains impossible in the standard sense. For instance, in the quotient ring , the elements 2 and 3 are zero divisors since , yet there is no universal mechanism for dividing by zero, as zero still has no inverse. This structure highlights how zero divisors create "dead ends" in multiplication, but do not resolve the core issue of inverting zero itself. Such rings are integral to algebraic number theory and modular arithmetic, but their limitations underscore the need for extended structures to handle division by zero. To address division by zero directly, wheel theory extends commutative rings (or semirings) by incorporating an additional element that formalizes such operations. Introduced in the early 2000s but building on ideas from the 1970s, including mathematician John Conway's concept of nullity denoted , wheels define division by zero using this absorbing element. Specifically, for a wheel extending a ring , the slash operation (division) satisfies for , , and for . Multiplication interacts with such that for , making an absorbing element, while . In the wheel of the real numbers, for example, , capturing the indeterminate nature of zero division without leading to infinity.[24][65] Despite these innovations, wheels have significant limitations that restrict their applicability. The slash operation in wheels is not associative—meaning in general—which deviates from the associativity axiom of ring multiplication and complicates algebraic manipulations. This non-associativity arises from the absorbing properties of , as propagating nullity through expressions often collapses them irretrievably. Consequently, while wheels provide a consistent framework for defining division by zero and managing zero divisors in an extended ideal, they are primarily theoretical tools rather than practical replacements for fields in most computations. In linear algebra contexts, such as matrix rings, similar issues manifest as singularities, where non-invertible matrices (analogous to zero divisors) prevent unique solutions, but wheels offer a broader algebraic perspective beyond vector spaces.[65]Computational Implementations

Floating-Point Systems

In floating-point systems that conform to the IEEE 754 standard, division by zero is explicitly defined to produce special values rather than causing undefined behavior or program termination, enabling robust numerical computations. When the dividend is a finite nonzero value and the divisor is exactly zero, the operation yields a signed infinity, with the sign matching that of the dividend to preserve mathematical consistency. This signaling of the division-by-zero exception can be trapped if configured, but by default, it returns the infinity value. For instance, in binary floating-point arithmetic, dividing a positive finite number by zero results in positive infinity, while a negative dividend produces negative infinity: These outcomes reflect the standard's design to handle limits approaching zero in the denominator, aligning with asymptotic behavior in real analysis.[66][67] Indeterminate forms, however, produce a Not a Number (NaN) value to indicate invalid operations. Specifically, dividing zero by zero or infinity by infinity results in NaN, as these lack a well-defined limit. NaNs are distinguished by type: quiet NaNs propagate silently through further arithmetic without raising exceptions, facilitating error containment in computations, whereas signaling NaNs trigger an invalid operation exception upon use, aiding in debugging. The representation differentiates them via the most significant bit of the fraction field, with quiet NaNs having it set to 1.[68][69] In applications like scientific computing, particularly numerical integration, exact division by zero is often circumvented by adding a small epsilon (a value on the order of machine epsilon, approximately for double precision) to the denominator when it nears zero, preventing infinities or NaNs and ensuring stable approximations. This technique balances precision loss with avoidance of exceptional results in iterative algorithms.[70]Integer and Modular Arithmetic

In integer arithmetic, division by zero is generally undefined and leads to runtime errors or exceptions in computational systems to avoid invalid operations. For example, in programming languages like Python, attempting to perform integer division by zero, such as10 // 0, raises a ZeroDivisionError exception, indicating that the operation is not permissible.[71] This behavior ensures that programs halt or handle the error explicitly, preventing propagation of erroneous results. Similarly, hardware implementations enforce this: on x86 architectures, the integer division instruction (DIV or IDIV) triggers a #DE (Divide Error) exception when the divisor is zero, interrupting execution and transferring control to an exception handler as specified in the Intel architecture manuals.[72]

For arbitrary-precision integer libraries, such as the GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library (GMP), division by zero is explicitly undefined, requiring users to perform zero checks before invoking division functions like mpz_tdiv_q to avoid undefined behavior or crashes.[73] GMP's design prioritizes performance for large integers but delegates error handling to the application layer, where programmers must verify that the divisor is non-zero, often using functions like mpz_cmp_si for comparison.

In modular arithmetic, division by an element is interpreted as multiplication by its modular multiplicative inverse. In the ring ℤ/mℤ, an element has a multiplicative inverse modulo if and only if , meaning and are coprime.[74] Consequently, when , (for ), so no inverse exists, rendering division by zero undefined in this context. This absence of an inverse prevents solving equations like , as it would imply , a contradiction.

A special case arises in the finite field where is prime, forming a field where every non-zero element is invertible. Here, division by zero remains undefined, as 0 lacks an inverse, but inverses for non-zero can be computed efficiently using Fermat's Little Theorem: for .[75] This theorem underpins modular exponentiation algorithms in cryptography and number theory, ensuring that division operations are well-defined except precisely at zero. In contrast to floating-point systems, which may produce infinities, integer and modular arithmetic strictly avoids such extensions, opting for exceptions or non-computability to maintain exactness.

Formal Verification Tools

In proof assistants based on dependent type theory, such as Coq and Lean, division is typically defined as a partial function with explicit preconditions ensuring the divisor is nonzero, leveraging dependent types to encode these constraints at the type level. For instance, in Coq, the division operation can be specified with a type like{n m : nat | m <> 0} -> n / m, where the proof of m <> 0 is required for the term to be well-typed, preventing invalid divisions from being constructed during verification.[76] Similarly, Lean's mathlib library defines natural number division using dependent pairs that pair the operands with a proof of positivity for the divisor, ensuring that proofs involving division remain sound only under valid conditions.[77] This approach integrates the undefined nature of division by zero directly into the type system, allowing formal proofs to reason about arithmetic without risking inconsistencies from invalid operations.

In Isabelle/HOL, which employs a classical higher-order logic with total functions, division by zero is conventionally defined to yield zero (e.g., a / 0 = 0), but this totalization is handled carefully in proofs to avoid unsoundness. For example, when verifying properties like the division algorithm, assumptions of a nonzero divisor lead to contradictions (manifesting as False) if division by zero is implicitly invoked, as the logic's axioms (such as field properties excluding zero inverses) ensure that any derivation assuming a / 0 in a context requiring invertibility derives a falsehood.[78] This setup allows Isabelle to maintain totality for computational convenience while using proof obligations to enforce mathematical correctness, distinguishing verified theorems from mere definitional equalities.

To manage partiality more explicitly across various proof assistants, division is often totalized using option types or similar constructs, where successful division returns Some(result) and failure (due to zero divisor) returns None. This pattern appears in systems like Coq's standard library extensions and Lean's partial function encodings, enabling compositional verification by propagating uncertainty through monadic structures or pattern matching, without altering core arithmetic axioms.[79] Such totalized representations facilitate exhaustive case analysis in proofs, ensuring that branches handling None explicitly address undefined cases.

In verified software projects, tools like the CompCert C compiler demonstrate practical application of these principles by formally proving semantic preservation, including the absence of undefined behaviors such as division by zero in compiled code when the source adheres to defined semantics. CompCert's correctness theorem guarantees that if a Clight program (a verified subset of C) exhibits only defined behaviors—explicitly excluding operations like integer division by zero—then the generated assembly code matches those behaviors exactly, without introducing crashes or erroneous results.[80] This verification, conducted in Coq, covers optimizations and transformations while treating undefined behaviors (per the C standard) as outside the proof's scope, thereby ensuring reliability for safety-critical systems.

As of 2023, Agda's standard library provides libraries for safe arithmetic, such as Data.Nat.DivMod, where division and modulo operations are defined dependently on a proof that the divisor is positive (nonZero : [m > 0](/page/M×0)), avoiding division by zero entirely through type-level guarantees. This approach in Agda emphasizes constructive proofs and has been extended in user-contributed packages for verified numerical computations, aligning with the system's focus on totality and consistency.