Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

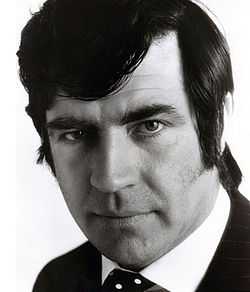

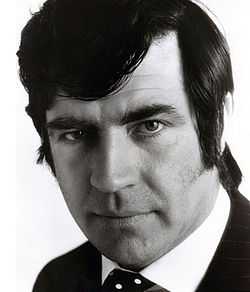

Alan Bates

View on Wikipedia

Sir Alan Arthur Bates (17 February 1934 – 27 December 2003) was an English actor who came to prominence in the 1960s, when he appeared in films ranging from Whistle Down the Wind to the kitchen sink drama A Kind of Loving.

Key Information

Bates is also known for his performance with Anthony Quinn in Zorba the Greek, as well as his roles in King of Hearts, Georgy Girl, Far From the Madding Crowd and The Fixer, for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. In 1969, he starred in the Ken Russell film Women in Love with Oliver Reed and Glenda Jackson.

Bates went on to star in The Go-Between, An Unmarried Woman, Nijinsky and in The Rose with Bette Midler, as well as many television dramas, including The Mayor of Casterbridge, Harold Pinter's The Collection, A Voyage Round My Father, An Englishman Abroad (as Guy Burgess) and Pack of Lies. He also appeared on the stage, notably in the plays of Simon Gray, such as Butley and Otherwise Engaged.

Early life

[edit]

Bates was born at the Queen Mary Nursing Home, Darley Abbey, Derby, England, on 17 February 1934, the eldest of three boys born to Florence Mary (née Wheatcroft), a housewife and a pianist, and Harold Arthur Bates, an insurance broker and a cellist.[1] They lived in Allestree, Derby, at the time of Bates's birth, but briefly moved to Mickleover before returning to Allestree.

Both his parents were amateur musicians who encouraged Bates to pursue music. By the age of 11, having decided to become an actor, he studied drama instead.[2] He further developed his vocation by attending productions at Derby's Little Theatre.

Bates was educated at the Herbert Strutt Grammar School, Derby Road, Belper, Derbyshire (now "Strutts", a volunteer led business and community centre) and later gained a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, where he studied with Albert Finney and Peter O'Toole, before leaving to join the RAF for National Service at RAF Newton.

Career

[edit]Early stage appearances

[edit]Bates's stage debut was in 1955, in You and Your Wife, in Coventry.[3]

In 1956, Bates made his West End debut as Cliff in Look Back in Anger, a role he had originated at the Royal Court and which made him a star. He also played the role on television (for the ITV Play of the Week) and on Broadway. He also was a member of the 1967 acting company at the Stratford Festival in Canada, playing the title role in Richard III.[4][5]

Television

[edit]In the late 1950s, Bates appeared in several plays for television in Britain in shows such as ITV Play of the Week, Armchair Theatre and ITV Television Playhouse.

In 1960, Bates appeared as Giorgio in the final episode of The Four Just Men (TV series) entitled Treviso Dam.

Bates worked for the Padded Wagon Moving Company in the early 1960s while acting at the Circle in the Square Theatre in New York City.

Film stardom (1960–1979)

[edit]Bates made his feature film debut in The Entertainer (1960) opposite Laurence Olivier, Joan Plowright, Albert Finney, and the rest of the ensemble cast. Bates played the lead in his second feature, Whistle Down the Wind (1961), opposite Hayley Mills and directed by Bryan Forbes.[6] He followed it with the lead in A Kind of Loving (1962), directed by John Schlesinger in his film debut. Both films were very popular in the UK, with the latter earning him a BAFTA nomination for Best Actor and establishing Bates as a film star.[7] Some film critics cited the 1963 crime drama The Running Man as being one of Bates's finest performances.[citation needed] The film starred Laurence Harvey as a man who fakes his death and Lee Remick as his increasingly conflicted wife, with Bates in the supporting role of Stephen Maddox, an insurance company investigator.

Bates next co-starred in an adaptation of Harold Pinter's The Caretaker (1963) along with Donald Pleasence and Robert Shaw. It was directed by Clive Donner, who then made Nothing But the Best (1964) with Bates. He was the co-lead alongside Anthony Quinn in the Academy Award-winning hit Michael Cacoyannis film Zorba the Greek (1964); the lead in a short film, Once Upon a Tractor (1965); and starred in Philippe de Broca's King of Hearts (1966).

Bates also starred as the male lead opposite Lynn Redgrave as the titular Georgy Girl (1966), which also featured James Mason and Charlotte Rampling in supporting roles. He was reunited with Schlesinger in Far From the Madding Crowd (1967), starring Julie Christie, Terence Stamp, and Peter Finch. For these two films, Bates earned himself three Golden Globe nominations: Best Comedy/Musical Actor and Best Male Newcomer; and Best Drama Actor the following ceremony, respectively.

In 1968, Bates starred alongside Dirk Bogarde and Ian Holm in the John Frankenheimer film The Fixer (1968), adapted from the Bernard Malamud novel based off the true story of Menahem Mendel Beilis. It earned Bates an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, as well as another Golden Globe nomination. He followed that up with Women in Love (1969), directed by Ken Russell and co-starring Oliver Reed and Glenda Jackson, in which Bates and Reed wrestled completely naked. The scene was groundbreaking for taboos of the time, as it was the first studio film to ever feature full frontal male nudity.[8] Bates also earned another BAFTA nomination for Best Actor for his performance.

Following that success, he appeared as Col Vershinin in the National Theatre's film of Three Sisters, reuniting him with Olivier (who directed) and Plowight.[9] He was handpicked by director Schlesinger to play the male lead in the film Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971). However, he was preoccupied filming The Go-Between (1971) for director Joseph Losey alongside Christie again, and had also become a father around that time, so thusly refused the role (which ultimately went to Finch opposite co-lead Jackson).

Bates starred in the film adaptation of A Day in the Death of Joe Egg (1972) with Janet Suzman and produced and appeared in a short, Second Best (1972). He starred in Story of a Love Story (1973). He also starred in two adaptations of his successful theatrical roles: his Tony-winning role in Butley (1974), as well as In Celebration (1975). He was the villain in Royal Flash (1975). He appeared alongside Susannah York and John Hurt in The Shout (1978); and opposite Jill Clayburgh in An Unmarried Woman (1978). He also played Bette Midler's ruthless business manager in the film The Rose (1979).

Film and television (1980s)

[edit]Bates starred in the TV movie Piccadilly Circus (1977) and The Mayor of Casterbridge (1978). In the latter he played Michael Henchard, the ultimately-disgraced lead, which he described as his favourite role. Bates played two diametrically opposed roles in An Englishman Abroad (1983), as Guy Burgess, a gay member of the Cambridge spy ring exiled in Moscow, and in Pack of Lies (1987), as a British Secret Service agent tracking several Soviet spies.

His film roles this decade were more sparse, but included Herbert Ross's Nijinsky (1980), in which he portrayed yet another role as both a closeted gay lover and a domineering mentor. The following year, he was part of James Ivory's Quartet (1981), also starring Maggie Smith, Isabelle Adjani, and Anthony Higgins. Bates succeeded that with The Return of the Soldier (1982), which reunited him with Julie Christie, Glenda Jackson, and Ian Holm. The Wicked Lady (1983) teamed him up with Faye Dunaway but received poor reviews.

Bates then starred alongside Julie Andrews as the husband of her violinist who is stricken with multiple sclerosis in Duet for One (1986). In the North Irish IRA thriller A Prayer for the Dying (1987) from director Mike Hodges, he plays the main antagonist opposite Mickey Rourke and Bob Hoskins. And in We Think the World of You (1988), he portrays the older lover of young convict Gary Oldman—the latter of whom gets sent to jail and entrusts his beloved, mischievous German Shepherd (a.k.a. Alsatian) to the former's care.

Later career

[edit]Bates continued working in film and television in the 1990s, including the role of Claudius in Franco Zeffirelli's version of Hamlet (1990). In 2001 he joined an all-star cast in Robert Altman's critically acclaimed period drama Gosford Park, in which he played the butler Jennings. He later played Antonius Agrippa in the 2004 TV film Spartacus, but died before it premiered. The film was dedicated to his memory and that of writer Howard Fast, who wrote the original novel that inspired the film Spartacus by Stanley Kubrick.

On stage, Bates had a particular association with the plays of Simon Gray, appearing in Butley, Otherwise Engaged, Stage Struck, Melon, Life Support, and Simply Disconnected, as well as the film of Butley and Gray's TV series Unnatural Pursuits. In Otherwise Engaged, his co-star was Ian Charleson, who became a friend, and Bates later contributed a chapter to a 1990 book on his colleague after Charleson's early death.[10]

Bates was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1995 Birthday Honours,[11] and was knighted in the 2003 New Year Honours, in both cases for services to drama.[12][13] He was an Associate Member of RADA,[citation needed] and was a patron of The Actors Centre, Covent Garden, London, from 1994 until his death in 2003.[14][15]

Personal life

[edit]

Bates had numerous gay relationships, including long-term affairs with actor Nickolas Grace and Olympic skater John Curry, as detailed in Donald Spoto's authorised biography Otherwise Engaged: The Life of Alan Bates.[16]

Bates privately admitted to being bisexual or homosexual at different points in his life; Spoto characterised Bates's sexuality as ambiguous, stating, "He liked to appear publicly with women and cuddle with them privately. However, his serious romances and most passionate sexual life occurred with men. [...] In his private life, he wanted most of all to have one true and enduring relationship, to love and be loved by one faithful man."[17] Even after homosexuality was partially decriminalised in England in 1967, Bates rigorously avoided interviews and questions about his personal life, and even denied to his male lovers that there was a homosexual component in his nature.[18][16]

Bates was married to actress Valerie 'Victoria' Ward from 1970 until her death from a heart attack associated with wasting disease in 1992, though the two had separated early in their marriage around 1973.[19] They had twin sons, born in November 1970: the actors Benedick Bates and Tristan Bates.[20] Tristan died following an ingestion of alcohol and either opium or heroin in Tokyo in 1990, devastating Bates.[21] In the later years of his life, Bates had a brief relationship with the Welsh actress Angharad Rees, though this faced the complexities of Bates' need for independence and predilection for male companionship.[22][21]

Throughout his life, Bates sought to be regarded as charming and charismatic, or at least as a man who, as an actor, could appear attractive to and attracted by women. He also chose some roles with an aspect of homosexuality or bisexuality, including the role of Rupert in the 1969 film Women in Love and the role of Frank in the 1988 film We Think the World of You.[16]

Death

[edit]Following a battle with diabetes and a stroke, Bates died of pancreatic cancer on 27 December 2003, after slipping into a coma.[23] He was buried at All Saints' Church, Bradbourne in Derbyshire.[24] Bates bequeathed companion and actress Joanna Pettet £95,000 (equivalent to £189,712 in 2023) upon his death. The two had been friends since 1964, and Pettet provided support and companionship during his final months after he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in February 2003. Pettet was quoted as saying: "It was a very touching gesture because he had done everything while he was in hospital to make sure I would be looked after following his death."[25]

Otherwise Engaged: The Life of Alan Bates

[edit]Donald Spoto's 2007 book, Otherwise Engaged: The Life of Alan Bates,[21] is a posthumous authorised biography of Alan Bates. It was written with the cooperation of his son Benedick and brother Martin, and features more than one hundred interviews, including with Michael Linnit and Rosalind Chatto.

Tristan Bates Theatre

[edit]Bates and his family created the Tristan Bates Theatre at the Actors' Centre in Covent Garden, in memory of his son Tristan who died at the age of 19.[26] Tristan's twin brother, Benedick, is a vice-director.[27]

Selected credits

[edit]FILM:

- The Entertainer (1960)

- Whistle Down the Wind (1961)

- A Kind of Loving (1962)

- The Caretaker (1963)

- The Running Man (1963)

- Nothing but the Best (1964)

- Zorba the Greek (1964)

- Georgy Girl (1966)

- King of Hearts (1966)

- Far from the Madding Crowd (1967)

- The Fixer (1968)

- Women in Love (1969)

- Three Sisters (1970)

- The Go-Between (1971)

- A Day in the Death of Joe Egg (1972)

- Butley (1974)

- In Celebration (1975)

- The Shout (1978)

- An Unmarried Woman (1978)

- The Rose (1979)

- The Return of the Soldier (1982)

- We Think the World of You (1988)

- Hamlet (1990)

- Gosford Park (2001)

- The Mothman Prophecies (2002)

- The Sum of All Fears (2002)

STAGE:

- Look Back in Anger (1956)

- Long Day's Journey into Night (1958)

- The Caretaker (1960)

- Butley (1971; 1973)

- Otherwise Engaged (1975)

- A Patriot for Me (1983)

- One for the Road (1984)

- Fortune's Fool (1996; 2002)

TELEVISION:

- The Mayor of Casterbridge (1978)

- A Voyage Round My Father (1982)

- An Englishman Abroad (1983)

- The Dog It Was That Died (1989)

- 102 Boulevard Haussmann (1991)‡

- Oliver's Travels (1995)

- Nicholas's Gift (1998)

- Love in a Cold Climate (2001)

‡This mini-film was shown as part of a presentation on the anthology series, Screen Two.

Accolades

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Alan Bates Biography". filmreference.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ Karen Rappaport. "Alan Bates Biography". The Alan Bates Archive. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ "Alan Bates Archive Feature: Timeline I, 1954–69". Archived from the original on 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Alan Bates acting credits". Stratford Festival Archives. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Whitaker, Herbert (8 April 1967), "The credo of Alan Bates: aim for variety", The Globe and Mail, p. 26

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (11 July 2025). "Forgotten British Film Studios: The Rank Organisation, 1961". Filmink. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (21 January 2025). "Forgotten British Moguls: Nat Cohen – Part Three (1962-68)". Filmink. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ Hofler, Robert (27 May 2020). "How Larry Kramer Pulled Off the First Film With Frontal Male Nudity – Back in 1969". Y! Entertainment. Yahoo!. Retrieved 28 May 2025 – via Larry Kramer.

Lord John Trevelyan: 'We had to consider this carefully, but decided to pass it; in a scene this was a milestone in censorship since male frontal nudity was still a rarity. We had little criticism, possibly because of the film's undoubted brilliance.'

- ^ "Three Sisters (1970)". IMDb. 2 March 1973.

- ^ Ian McKellen, Alan Bates, Hugh Hudson, et al. For Ian Charleson: A Tribute. London: Constable and Company, 1990. pp. 1–5.

- ^ The United Kingdom:"No. 54066". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 16 June 1995. p. 8.

- ^ "No. 56797". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2002. p. 1.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (29 December 2003). "Actor Sir Alan Bates, 69, dies after cancer battle". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Learn More". actor at the centre. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "In the Name of the Son: Alan Bates Bails Out UK's Actors Centre". Playbill. 3 September 2001.

- ^ a b c Belonsky, Andrew (21 May 2007). "New Bio Outs Late, Great, "Gay" Alan Bates / Queerty". Queerty. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Coveney, Michael (16 June 2007). "Review: Otherwise Engaged by Donald Spoto". The Guardian. p. 401. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Albany Trust Homosexual Law Reform Society (1984). "GB 0097 HCA/Albany Trust". AIM25. British Library of Political and Economic Science. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ^ "BBC – Derby – Around Derby – Famous Derby – Sir Alan Bates biography".

- ^ Lewis, Roger (28 June 2007). "The Minute They Got Close, He Ran". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Spoto, Donald (2007). Otherwise Engaged: The Life of Alan Bates. London: Hutchinson. pp. 320–321, 391. ISBN 978-0-09-179735-5.

- ^ "Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes leads tributes to Angharad Rees". The Daily Telegraph. London. 28 September 2012.

- ^ "The minute they got close, he ran". 28 June 2007.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 2864). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Alan Bates's £95,000 for secret lover who nursed him through his final days". Evening Standard. ESI Media. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Michael Billington (29 December 2003). "Sir Alan Bates". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ "About Tristan Bates Theatre". Tristan Bates Theatre. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

External links

[edit]- Alan Bates at IMDb

- Alan Bates at the TCM Movie Database

- Alan Bates at the Internet Broadway Database

- Alan Bates at the BFI's Screenonline

Alan Bates

View on GrokipediaEarly life and education

Childhood and family background

Alan Arthur Bates was born on 17 February 1934 in Allestree, Derbyshire, England, the eldest of three sons born to Florence Mary Bates (née Wheatcroft), a homemaker, and Harold Arthur Bates, an insurance broker.[2][6][7] The family resided in the industrial Midlands region during the economic hardships of the 1930s and the disruptions of World War II, with Bates experiencing the rationing and austerity that characterized British working-class life in that era.[8][7] Bates's parents were amateur musicians—his father played piano, and his mother encouraged artistic pursuits—which exposed him to performance from an early age, though the household emphasized modest self-reliance over formal cultural privileges.[2][7] At age 11, while attending grammar school in nearby Belper, Bates decided to become an actor, shifting from musical interests to drama through local school productions and familial encouragement, reflecting personal initiative in a context of limited resources.[9][10] This formative environment in post-war Derbyshire shaped Bates's ambition, prompting his relocation to London as a teenager to access greater opportunities, undeterred by the era's socioeconomic constraints.[9][8]Dramatic training and early aspirations

Bates secured a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) following his grammar school education in Derbyshire, commencing formal training in 1951.[11][12] This period was interrupted by compulsory National Service, during which he served two years in the Royal Air Force, a requirement for males of his generation that delayed many personal ambitions including artistic pursuits.[11][13] Resuming studies post-discharge, Bates completed the intensive three-year program at RADA—emphasizing voice, movement, and interpretive skills—graduating in 1954 alongside contemporaries Peter O'Toole and Albert Finney.[14][15] His path to admission via competitive scholarship, rather than familial or social leverage, highlighted the era's emphasis on raw talent and perseverance amid economic constraints and mandatory duties, with entry rates to such institutions remaining low due to limited spots and high applicant volumes.[11]Stage career

Debut and breakthrough roles

Bates's entry into professional theatre followed repertory work with the Midland Theatre Company in Coventry, where he appeared in You and Your Wife in 1955.[16] His London debut came on April 2, 1956, portraying Simon Fellowes in Angus Wilson's The Mulberry Bush at the Royal Court Theatre, the English Stage Company's opening production under George Devine.[17][16] This venue spearheaded a post-World War II shift in British theatre, favoring gritty, ensemble-driven realism over escapist verse drama and upper-class satires amid economic austerity and social upheaval.[18] Breakthrough arrived shortly after with Bates originating the role of Cliff Lewis, the empathetic sidekick to the volatile Jimmy Porter, in John Osborne's Look Back in Anger, which premiered at the Royal Court on May 8, 1956.[19][20] The production ignited the "Angry Young Men" ethos, channeling provincial frustration through colloquial dialogue and domestic strife, provoking backlash from critics wedded to formal elocution for its abrasive naturalism yet earning acclaim for mirroring demobilized veterans' alienation.[18][3] Bates embodied Cliff's quiet loyalty with subdued intensity, distinguishing himself in a cast including Kenneth Haigh as Porter, amid a surge of RADA-trained peers vying for roles in this raw idiom.[3] The play transferred to the West End's Lyric Theatre on November 21, 1956, with Bates continuing in the role through extended runs totaling two years, cementing his transition from provincial repertory to commercial viability.[3] In 1958, he portrayed the introspective Edmund Tyrone in Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night during its British premiere at the Edinburgh International Festival on August 25, followed by a London engagement at the St. James's Theatre.[21] This demanding depiction of familial dysfunction and morphine addiction highlighted Bates's affinity for tormented youth figures, navigating a landscape where naturalistic demands tested actors against entrenched West End stars favoring lighter fare.[21]Major theatrical achievements and collaborations

Bates garnered international acclaim for his portrayal of Ben Butley in Simon Gray's play Butley, which premiered at the Criterion Theatre in London on 8 June 1971 before transferring to Broadway's Morosco Theatre on 23 October 1972, where he won the Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play in 1973.[22][23] His interpretation of the acerbic, self-destructive academic was praised for its restrained intensity, allowing underlying violence and pathos to emerge organically, though some reviewers noted the character's unraveling risked veering into mannerism under prolonged scrutiny.[24] In Gray's Otherwise Engaged (Queen's Theatre, London, opening 12 July 1975), Bates played the detached Simon Hench, earning the Variety Club of Great Britain Best Actor award for a performance that balanced comic detachment with simmering domestic tensions, highlighting his affinity for Gray's incisive examinations of middle-class malaise. This collaboration marked the first of several with Gray, including Stage Struck (1979) and Melon (1987), underscoring Bates's versatility in modern roles that demanded nuanced emotional authenticity over histrionics. Critics lauded his ability to convey suppressed turmoil without overt intensification, though occasional detractors argued his understated approach could dilute dramatic peaks in ensemble dynamics.[8] Bates tackled classical repertoire selectively, reviving Hamlet at the Nottingham Playhouse in 1972 under Robin Phillips, a production emphasizing introspective torment amid political intrigue, which reinforced his command of Shakespearean complexity before his Butley Broadway run.[25] Later, he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company for Antony in Antony and Cleopatra (1999–2000, directed by Gregory Thompson), portraying a reflective, elegiac lover whose tenderness disarmed audiences, though some critiques observed a dissipated restraint over the role's expected reckless obsession.[26][13] His partnerships extended to directors like Peter Hall, including the title role in Ibsen's The Master Builder (1995), where his portrayal of self-deluded ambition blended psychological depth with physical frailty, exemplifying his shift toward mature, introspective classical interpretations.[27] A late-career highlight came with Ivan Turgenev's Fortune's Fool on Broadway (2002, directed by Jack O'Brien), earning Bates his second Tony Award for Best Leading Actor in a Play and Drama Desk recognition for a vaudevillian nobleman whose hapless charm masked profound pathos, affirming his enduring stage prowess into his sixties.[28][29] These achievements reflected Bates's strength in roles requiring emotional realism—contrasting his modern versatility with selectively received classical efforts—while collaborations with Gray and institutions like the RSC solidified his reputation for authentic, unembellished portrayals over stylized excess.Film career

Early film roles and rising stardom (1950s–1960s)

Bates entered cinema with a supporting role as one of Laurence Olivier's sons in The Entertainer (1960), Tony Richardson's adaptation of John Osborne's play that captured post-war British disillusionment.[1] This debut marked his transition from stage to screen, showcasing his ability to embody youthful angst amid Olivier's domineering performance. He followed with his first lead in Whistle Down the Wind (1961), directed by Bryan Forbes, portraying an escaped convict sheltered by children who mistake him for a Christ-like figure, highlighting his capacity for nuanced vulnerability in a rural Lancashire setting.[30] His breakthrough arrived in A Kind of Loving (1962), John Schlesinger's kitchen-sink drama where Bates played Vic Brown, a young draftsman trapped in an unplanned marriage, earning a BAFTA nomination for Best British Actor.[31] The film resonated commercially, ranking among the year's top UK box-office draws and cementing Bates's reputation for authentic portrayals of working-class masculinity under social strain.[32] Throughout the mid-1960s, he tackled anti-heroic roles reflecting the era's sexual and cultural upheavals, including Basil, the repressed intellectual befriended by Anthony Quinn's exuberant Zorba in Zorba the Greek (1964), a critical and commercial success that earned Quinn an Oscar nomination. In Georgy Girl (1966), Bates portrayed the bohemian Jos, entangled in a modern London love quadrangle, earning a Golden Globe nod for New Star of the Year – Actor and contributing to the film's Oscar-nominated cultural snapshot of swinging sixties mores.[33] Bates further solidified his stardom as the steadfast shepherd Gabriel Oak in Far from the Madding Crowd (1967), John Schlesinger's lavish Thomas Hardy adaptation opposite Julie Christie, where his restrained intensity contrasted the period's romantic turbulence.[34] The decade closed with Women in Love (1969), Ken Russell's bold D.H. Lawrence adaptation, in which Bates's Gerald Crich wrestled nude with Oliver Reed's Birkin, sparking BBFC censorship debates resolved via a confidential agreement with chief examiner John Trevelyan after minor edits.[35] This scene, featuring full-frontal male nudity, challenged taboos and advanced depictions of male physical and emotional exposure amid the sexual revolution.[36]