Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

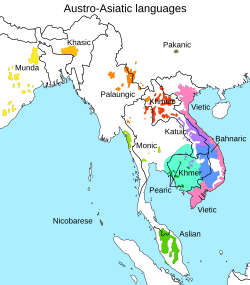

Aslian languages

View on Wikipedia| Aslian | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Peninsular Malaysia and Southern Thailand |

| Linguistic classification | Austroasiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Aslian |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | asli1243 |

Aslian | |

The Aslian languages (/ˈæsliən/) are the southernmost branch of Austroasiatic languages spoken on the Malay Peninsula. They are the languages of many of the Orang Asli, the aboriginal inhabitants of the peninsula. The total number of native speakers of Aslian languages is about fifty thousand and all are in danger of extinction. Aslian languages recognized by the Malaysian administration include Kensiu, Kintaq, Jahai, Minriq, Batek, Cheq Wong, Lanoh, Temiar, Semai, Jah Hut, Mah Meri, Semaq Beri, Semelai and Temoq.[1]

History and origin

[edit]Aslian languages originally appeared on the western side of the main mountains and eventually spread eastwards into Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang.[2] The nearest relatives to the Aslian languages are Monic and Nicobarese.[3] There is a possibility the early Monic and Nicobarese people had contact with the migrants who moved into the Malay Peninsula from further north.

Aslian languages contain a complex palimpsest of loanwords from linguistic communities that no longer exist on the Malay Peninsula. Their former residence can be traced from the etymologies and the archaeological evidence for the succession of cultures in the region. Roger Blench (2006)[4] notes that Aslian languages have many Bornean and Chamic loanwords, pointing to a former presence of Bornean and Chamic speakers on the Malay Peninsula.

Blagden (1906),[5] Evans (1937)[6] and Blench (2006)[4] note that Aslian languages, especially the Northern Aslian (Jahaic) group, contain many words that cannot be traced to any currently known language family. The extinct Kenaboi language of Negeri Sembilan also contains many words of unknown origin in addition to words of Austroasiatic and Austronesian origin.

Sidwell (2023) proposed that Proto-Aslian had arrived in the Malay Peninsula from the Gulf of Thailand region prior to Mon dominance, and was part of an early southern dispersal that also included Nicobaric. Due to its early split from the rest of Austroasiatic, Aslian contains many retentions and has escaped the areal influences that had later swept mainland Southeast Asia. Aslian likely arrived at around the Pahang area and then spread inland and upstream.[7]

Classification

[edit]- Jahaic languages ("Northern Aslian"): Cheq Wong; Ten'edn (Mos); (Eastern) Batek, Jahai, Minriq, Mintil; (Western) Kensiu, Kintaq (Kentaqbong).

- Senoic languages ("Central Aslian"): Semai, Temiar, Lanoh, *Sabüm, Semnam.

- Southern Aslian languages (Semelaic): Mah Meri (Besisi), Semelai, Temoq, Semaq Beri.

- Jah Hut.

The extinct Kenaboi language is unclassified, and may or may not be Aslian.

Phillips (2012:194)[8] lists the following consonant sound changes that each Aslian branch had innovated from Proto-Aslian.

- Northern Aslian: Proto-Aslian *sə- > ha-

- Southern Aslian: loss of Proto-Aslian *-ʔ (final glottal stop)

- Proto-Aslian *-N > *-DN in all branches except Jah Hut

Reconstruction

[edit]The Proto-Aslian language has been reconstructed by Timothy Phillips (2012).[8]

Phonology

[edit]Syllable structure

[edit]Aslian words may either be monosyllabic, sesquisyllabic or disyllabic:

- Monosyllabic: either simple CV(C) or complex CCV(C).[9]

- Sesquisyllabic:[10] consist of a major syllable with fully stressed vowel, preceded by a minor syllable

- Temiar ləpud 'caudal fin'

- Semai kʔɛːp [kɛʔɛːp] 'centipede'[11]

- Disyllabic: more morphologically complex, resulting from various reduplications and infixations. Compounds with unreduced though unstressed vowels also occur:

- Temiar diŋ-rəb 'shelter'

- Loanwords from Malay are a further source of disyllables:

- Jah Hut suraʔ 'sing', from Malay; suara 'voice'

- Semai tiba:ʔ 'arrive', from Malay; tiba 'arrive'[12]

- Temiar even has phonetic trisyllables in morphological categories such as the middle causative (tərakɔ̄w)[13] and the continuative causative (tərɛwkɔ̄w), or in words with proclitics (barhalab ~ behalab 'go downriver').

Initial consonants

[edit]Aslian words generally start with a consonant. Words which start with a vowel will be followed by a glottal stop.[2] In most Aslian languages, aspirated consonants are analyzed as sequences of two phonemes, one of which happens to be h.

Aslian syllable-initial consonant clusters are rich and varied. Stops for example may cluster without restrictions to their place of articulation or voicing:

- Jah Hut tkak 'palate', dkaŋ 'bamboo rat', bkul 'gray', bgɔk 'goiter'[14]

Articulation of laryngeal consonants /h, ʔ/ may be superimposed upon the vowel midway in its articulation, giving the impression of two identical vowels interrupted by the laryngeals.

- Jah Hut /jʔaŋ/ [jaʔaŋ] 'bone', /ɲhɔːʡ/ [ɲɔˑhɔˑʡ] 'tree'[11]

Vowels

[edit]A typical Aslian vowel system is displayed by Northern Temiar, which has 30 vocalic nuclei.[13]

| Oral | Nasal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i ʉ u | iː ʉː uː | ĩ ʉ̃ ũ | ĩː ʉ̃ː ũː |

| Mid | e ə o | eː əː oː | N/A | N/A |

| Open | ɛ a ɔ | ɛː aː ɔː | ɛ̃ ã ɔ̃ | ɛ̃ː ãː ɔ̃ː |

The functional load of the nasal/oral contrast is not very high in Aslian languages (not many minimal pairs can be cited). Diffloth[15] states that this phenomenon is unpredictable and irregular in Semai dialects, especially on vowels preceded by h- or ʔ-.

Phonemic vowel length has been retained in Senoic languages such as Semai, Temiar and Sabum. Contrastive length has been lost in the Northern and Southern Aslian branches. The loss of vowel length must have led to complex reorganizations in the vocalic systems of the affected languages, by developing new contrasts elsewhere.

Diphthongization is not as obvious in Aslian languages as compared to the other branches of Mon–Khmer. Proto-Semai is reconstructed with 10-11 long monophthongal vowels, but with only one diphthong, /iə/.[9]

Senoic infixes are sensitive to the number of initial consonants in a root. Rising diphthongs like [i̯ə] or [u̯ə] are ambiguous, since the glide may be interpreted as either a feature of the initial or of the vowel.

Final consonants

[edit]Aslian languages are well endowed with final consonants,[9] with most of the languages placing a lot of stress on them.[2]

- -r, -l, -s, -h and -ʔ are represented and well-preserved in Aslian.[16] There is also a tendency to shorten long vowels before these finals.[17]

It has been reported that Temiar -h has bilabial friction after -u-, e.g. /tuh/ 'speak' pronounced as [tuɸ].[13]

Throughout the Aslian family, final nasals are pre-stopped. In Northern Aslian this has gone further, with final nasals merging with the plosive series.

Morphology

[edit]All Aslian languages that have been thoroughly studied have constructive usage of various morphophonemic devices – prefixation, infixation and reduplication. Also, most Aslian languages preserve fossilized traces of other morphological patterns that are no longer productive.[9]

It was also noted that the use of the suffix in Aslian languages was a product of recent use of Malay loan words. For example, the use of the infix 'n' is prominent in various Aslian language and it encompasses a myriad of definition.[2]

Simple prefixation

[edit]- C(C)VC → (P)(P)–C(C)VC

Example: Jah Hut causatives[9]

| Affixes | Simplex | Causative |

|---|---|---|

| p- | cyɛk 'sleep' | pcyɛk 'put to sleep' |

| pr- | bhec 'be afraid' | prbhec 'frighten' |

| pn- | tlas 'escape' | pntlas 'release' |

| tr- | hus 'get loose (clothes)' | trhus 'undress' |

| kr- | lʉy 'be inside' | krlʉy 'put inside' |

Simple infixation

[edit]Source:[9]

- C (C) V C → C-I-(C) V C

Aslian languages insert infixes between two consonants. Simple infixation is when the infix is inserted into the root. The most important liquid infix is the causative -r-, which is productive in Semai and Temiar.

- Semai (root has 2 initial consonants, infix comes between them): kʔā:c 'be wet', krʔā:c 'moisten something'.[18]

Nasal infixes are also found in Aslian, especially used as nominalizers of verbal roots.

- Jah Hut (the agentive nominalizing prefix is mʔ-): lyɛp 'plait palm leaves' → mlayɛp 'one who plaits'; cyɛk 'sleep' → mʔcyɛk 'one who sleeps a lot'

Reduplicative infixation: incopyfixation

[edit]Source:[9]

A reduplication of the final consonant of the root is being infixed to the root. This process[11] occurs in all 3 branches of Aslian.

- Incopyfix of final alone (roots complex by nature):[9]

- Kensiw: plɔɲ 'sing' → pɲlɔɲ 'singing'

- Che' Wong: hwæc 'whistle' → hcwæc 'whistling'

- Root-external infix plus incopyfix.[9] In Semai, count nouns are derived from mass nouns by using a root-external nasal infix and an incopyfix of the final. When the root-initial is simple, the incopyfix precedes the infix:

- teːw 'river' (mass) →twneːw [tuniːw] 'id.' (count).

When the root-initial is complex, the infix precedes the incopyfix: - slaːy 'swidden' (mass) → snylaːy [snilaːj] 'id.' (count)

- teːw 'river' (mass) →twneːw [tuniːw] 'id.' (count).

- Root-external prefix plus incopyfix.[9] Simple-initialled verbs are formed by inserting the prefix n- and incopyfixing the final between prefix and the root-initial:

- Batek: jɯk 'breathe' → nkjɯk 'the act of breathing'

- Reduplication of the initial and a root-external infix.[9] This is present in Semai and Temiar, which have a verbal infix -a-. In Semai, it forms resultative verbs, while in Temiar, it marks the 'simulfactive aspect'.[19] In both languages, if the root has two consonants, the suffix-a- is inserted between them:

- Semai: slɔːr 'lay flat objects into round container' → salɔːr 'be in layers (in round container)'

- Temiar: slɔg 'lie down, sleep, marry' → salɔg 'go straight off to sleep'

If the consonant initial of the root is simple, it is reduplicated so that the -a- can be inserted between the original and its copy. - Semai: cɛ̃ːs 'tear off' → cacɛ̃ːs 'be torn off'

- Temiar: gəl 'sit' → gagəl 'sit down suddenly'

- Reduplication of the initial and incopyfixation of the final.[9] A simple initial is reduplicated for the incopyfixation of the final. In Aslian, this is used to derive the progressive verbs.[20]

- Batek (N.Aslian): kɯc 'grate' → kckɯc 'is grating'

- Semelai (S.Aslian): tʰəm 'pound' → tmtʰəm 'is pounding'

- Semai (Senoic): laal 'stick out one's tongue' → lllaal 'is sticking out one's tongue'

Grammar

[edit]Aslian syntax is presumably conservative with respect to Austroasiatic as a whole, though Malay influence is apparent in some details of the grammar (e.g. use of numeral classifiers).[9]

Basic and permuted word order

[edit]- Senoic sentences are prepositional and seem to fall into two basic types – process (active) and stative. In stative sentences, the predicate comes first:

Mənūʔ

VP

big

ʔəh

NP (Subject)

it

It's big.

- In process sentences, the subject normally comes first, with the object and all other complements following the verb:

Cwəʔ

NP (Subj)

yəh-

P (Pfx)

mʔmus

V

The dog growls.

- In Jah Hut, all are complements, but the direct object require a preposition:

ʔihãh

NP (Subj)

I

naʔ

Aux

INTENT

cɔp

V

stab

rap

N (Obj)

boar

tuy

Det

that

han

Prep

with

bulus

Obj

spear

I'll stab that boar with a spear

- Relative clauses, similar verbal modifiers, possessives, demonstratives and attributive nouns follow their head-noun:

ʔidɔh

NP (Subj)

this

pləʔ

N (H)

fruit

kɔm

Aux

can

bɔʔ-caʔ

P (Pfx) V

1PL-eat

This is a fruit which we can eat.

- The negative morpheme precedes the verb, though the personal prefix may intervene before the verb root:

ʔe-loʔ

why

why

tɔʔ

Neg

NEG

ha-rɛɲrec

P (Pfx V

2-eat

sej

N (h)

meat

mɛjmɛj

NP (Obj)

excellent

naʔ

Det

that

Why didn't you eat that excellent meat?

Deixis, directionality and voice

[edit]Senoic languages set much store by deictic precision. This manifests itself in their elaborate pronominal systems, which make inclusive/exclusive and dual/plural distinctions, and take the trouble to reflect the person and number of the subject by a prefixal concordpronoun on the verb.[9]

Locative deixis pays careful attention to the relative position (both horizontal and vertical) of speaker and hearer, even when it may be quite irrelevant to the message:

yēʔ

Pron

doh

LOC

ʔi-mʔog

P (Pfx)-Prt-V

ma hãʔ

Prep-pron

naʔ

LOC

I here will give it to you there. (I'll give it to you)

Lexicon and semantics

[edit]The Aslian languages have borrowed words from each other due to mutual contact.[1]

Austroasiatic languages have a penchant for encoding semantically complex ideas into unanalyzable, monomorphemic lexemes e.g. Semai thãʔ 'to make fun of elders sexually'.[21] Such lexical specificity makes for a proliferation of lexicon.

Lexicon elaboration is particularly great in areas which reflect the interaction of the Aslians with their natural environment (plant and animal nomenclature, swidden agriculture terminology etc.). The greatest single sweller of the Aslian vocabulary is the class of words called expressive.[22]

Expressives are words which describe sounds, visual phenomena, bodily sensations, emotions, smells, tastes etc., with minute precision and specificity.[9] They are characterized by special morphophonemic patterns, and make extensive use of sound symbolism. Unlike nouns and verbs, expressives are lexically non-discrete, in that they are subject to a virtually unlimited number of semantic nuancings that are conveyed by small changes in their pronunciation.

For example, in Semai, various noises and movements of flapping wings, thrashing fish etc. are depicted by an open set of morphophonemically related expressives like parparpar, krkpur, knapurpur, purpurpur etc.[9]

Influences from other languages

[edit]The Aslian languages have links with numerous languages. This is evident in the numerous borrowings from early Austronesian languages, specifically those from Borneo. There was a possibility that migrants from Borneo settled in the Malay Peninsula 3000–4000 years ago and established cultural dominance over the Aslian speakers. Aslian words also contain words of Chamic, Acehnese and Malayic origin.[3] For example, several Aslian languages made use of Austronesian classifiers, even though classifiers exist in the Aslian language.[23]

Aslian languages do not succumb to any great deal of phonological change, yet borrowings from Malay are substantial. This is a result of constant interactions between the Orang Asli and Malays around the region. There is a more significant Malay influence among the nomadic Orang Asli population than within the farming Orang Asli population, as the farmers tend to be situated in the more remote areas and lead a subsistence lifestyle, and thus are less affected by interaction with the Malay language.[2]

Endangerment and extinction

[edit]All Aslian languages are endangered as they are spoken by a small group of people, with contributing factors including speaker deaths and linguistic assimilation with the Malay community. Some efforts are being made to preserve the Aslian languages in Malaysia. Some radio stations in Malaysia broadcast in Aslian languages for nine hours every day. Other media such as newspapers, magazine-type programs and dramas are broadcast in Aslian languages.[2]

Only a small group of Orang Asli receive formal education in the Aslian languages. Most of the younger Orang Asli use Malay as the medium of instruction in school. There is currently only a total of 5 schools in the state of Pahang and 2 schools in the state of Perak which teach Aslian languages, due to the lack of qualified teachers and teaching aids, which are still in the process of development.[2]

Some Aslian languages are already extinct, such as Wila' (also called Bila' or Lowland Semang), which was recorded having been spoken on the Province Wellesley coast opposite Penang in the early 19th century. Another extinct language is Ple-Temer, which was previously spoken near Gerik in northern Perak.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Geoffrey Benjamin (1976) Austroasiatic Subgroupings and Prehistory in the Malay Peninsula Jenner et al Part I, pp. 37–128

- ^ a b c d e f g h Asmah Hji Omar (volume editor), 2004. 'Aslian languages', 'Aslian: characteristics and usage.', The encyclopedia of Malaysia, volume 12: Languages and literatures, Kuala Lumpur. Archipelago Press, pp. 46–49

- ^ a b Blench, R. (2006): Why are Aslian speakers Austronesian in culture Archived February 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Paper presented at the Preparatory meeting for ICAL-3, Siem Reap.

- ^ a b Blench, Roger. 2006. Why are Aslian speakers Austronesian in culture? Papers presented at ICAL-3, Siem Reap, Cambodia.

- ^ Blagden, C. O. 1906. ‘Language.’ In: W. W. Skeat and C. O. Blagden, Pagan races of the Malay Peninsula, volume 2, London: MacMillan, pp. 379-775.

- ^ Evans, I. H. N. 1937. The Negritos of Malaya. London: Frank Cass.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul (2023). Proto-Aslian reconstruction: classification, vocalism, homeland. SEALS 32 (32nd Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistic Society). Chiang Mai.

- ^ a b Phillips, Timothy C. 2012. Proto-Aslian: towards an understanding of its historical linguistic systems, principles and processes. Ph.D. thesis, Institut Alam Dan Tamadun Melayu Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Matissoff, J. 2003. Aslian: Mon–Khmer of Malay Peninsula Mon-Khmer Studies 33:1–58

- ^ Matisoff, James A, 1973. Tonogenesis in Southeast Asia. In Larry M. Hyman, ed., CTT 71-95

- ^ a b c Diffloth, Gerard.1976a. Minor-syllably vocalism in Senoic languages. In Jenner et al., Vol. I, pp 229–2480

- ^ Nik Safiah Karim and Ton Dinti Ibrahim. 1979. "Semoq Beri: some preliminary remarks." FMJ (n.s) 24:17–31

- ^ a b c Benjamin, Geoffrey. 1976b. "An outline of Temiar grammar". In Jenner et al, eds., Vol I, pp. 129–87 (OTG)

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1976c. "Jah Hut, an Austroasiatic language of Malaysia." In Nguyen Dang Liem, ed., SALS II:73-118, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics C-42

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1977. "Towards a history of Mon–Khmer: proto-Semai vowels." Tōnan Azia Kenkyū (Kyoto) 14(4):463-495

- ^ Benedict, Paul K. 1972. Sino-Tibetan: a Conspectus. Contributing ed., James A. Matisoff. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Shorto, Harry L. 1976. "The vocalism of Proto Mon–Khmer." In Jenner et al., eds., Vol. II, pp. 1041–1067

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1972b. Ambiguïtè morphologique en semai. In J. Thomas and L.Bernot, eds. LTNS I:91-93, Paris: Klincksieck

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1976a. "Minor-syllable vocalism in Senoic languages." In Jenner et al., Vol. I, pp. 229–248.

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1975. "Les langues mon-khmer de Malaisie: classification historique et innovations." ASEMI 6(4):1-19.

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1976e. "Relations between the animals and the humans in Semai society." Handout for lecture presented at Southeast Asian Center, Kyoto University, Nov. 25.

- ^ Diffloth, Gerard. 1976b. "Expressives in Semai". In Jenner et al., Vol. I, pp. 249–264.

- ^ Adams, L, Karen. 1991. "The Influence of Non-Austroasiatic Languages on Numeral Classification in Austroasiatic". Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 111, No. 1 (Jan–Mar 1991), pp. 62–81.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams, Karen Lee. Systems of Numeral Classification in the Mon–Khmer, Nicobarese and Aslian Subfamilies of Austroasiatic. [S.l: s.n.], 1982.

- Benjamin, Geoffrey (1976). "Austroasiatic subgroupings and prehistory in the Malay peninsula" (PDF). In Jenner, Philip N.; Thompson, Laurence C.; Starosta, Stanley (eds.). Austroasiatic Studies Part I. Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications. Vol. 13. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 37–128. JSTOR 20019154.

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2011. ‘The Aslian languages of Malaysia and Thailand: an assessment.’ In: Peter K. Austin & Stuart McGill (eds), Language Documentation and Description, Volume 11. London: Endangered Languages Project, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), pp. 136–230. ISSN 1740-6234 [2014:] www.elpublishing.org/PID/131.

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2014. ‘Aesthetic elements in Temiar grammar.’ In: Jeffrey Williams (ed.), The Aesthetics of Grammar: Sound and Meaning in the Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–60.[dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139030489.004]

- Burenhult, Niclas. 2005. A Grammar of Jahai. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Burenhult, Niclas. 2006. 'Body part terms in Jahai'. Language Sciences 28: 162–180.

- Burenhult, Niclas. 2008. 'Spatial coordinate systems in demonstrative meaning'. Linguistic Typology 12: 99–142.

- Burenhult, Niclas. 2008. 'Streams of words: hydrological lexicon in Jahai'. Language Sciences 30: 182–199.

- Burenhult, Niclas & Nicole Kruspe. 2016. 'The language of eating and drinking: a window on Orang Asli meaning-making'. In Kirk Endicott (ed.), Malaysia’s ‘Original People’: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli, Singapore, NUS Press, pp. 175–202.

- Burenhult, Niclas, Nicole Kruspe & Michael Dunn. 2011. 'Language history and culture groups among Austroasiatic-speaking foragers of the Malay Peninsula'. In, N. J. Enfield (ed.), Dynamics of Human Diversity: The Case of Mainland Southeast Asia, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, pp. 257–277.

- Dunn, Michael, Niclas Burenhult, Nicole Kruspe, Neele Becker & Sylvia Tufvesson. 2011. 'Aslian linguistic prehistory: A case study in computational phylogenetics'. Diachronica 28: 291–323.

- Dunn, Michael, Nicole Kruspe & Niclas Burenhult. 2013. 'Time and place in the prehistory of the Aslian language family'. Human Biology 85: 383– 399.

- Jenner, Philip N., Laurence C. Thompson, Stanley Starosta eds. (1976) Austroasiatic Studies Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications No. 13, 2 volumes, Honolulu, University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 0-8248-0280-2

- Kruspe, Nicole. 2004. A Grammar of Semelai. Cambridge Grammatical Descriptions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kruspe, Nicole. 2004. 'Adjectives in Semelai'. In R. M. W. Dixon & A. Y. Aikhenvald (eds.), Adjective classes: A Cross-linguistic Typology, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 283–305.

- Kruspe, Nicole. 2009. 'Loanwords in Ceq Wong, an Austroasiatic language of Peninsular Malaysia'. In Martin Haspelmath & Uri Tadmor (eds.), Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook of Lexical Borrowing, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 659–685.

- Kruspe, Nicole. 2010. A Dictionary of Mah Meri, As Spoken at Bukit Bangkong. Illustrated by Azman Zainal. Oceanic Linguistics special publication no. 36. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Kruspe, Nicole. 2015. 'Semaq Beri'. In Mathias Jenny & Paul Sidwell (eds), The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages, Volume 1, Leiden: Brill, pp. 475–518.

- Kruspe, Nicole, Niclas Burenhult & Ewelina Wnuk. 2015. 'Northern Aslian'. In Mathias Jenny & Paul Sidwell (eds), The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages, Volume 1, Leiden: Brill pp. 419–474.

- Wnuk, Ewelina & Niclas Burenhult. 2014. 'Contact and isolation in hunter-gatherer language dynamics: Evidence from Maniq phonology (Aslian, Malay Peninsula)'. Studies in Language 38: 956–981.

External links

[edit]- Ceq Wong (Chewong) Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- http://projekt.ht.lu.se/rwaai RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-6710-4@view Aslian languages in RWAAI Digital Archive

- Newly discovered Jedek language (Lund University, News and press release: Jedek language)

Aslian languages

View on GrokipediaGeographic Distribution and Speakers

Ethnic Groups and Population Estimates

The Aslian languages are spoken predominantly by the Orang Asli, the indigenous peoples of Peninsular Malaysia, who are classified into three primary ethnic categories: Negrito (also known as Semang), Senoi, and Proto-Malay (or Aboriginal Malay). These groups collectively form the ethnic base of Aslian speakers, with small additional communities in southern Thailand, such as the Maniq. Total Orang Asli population reached 206,777 as of the 2020 census, representing about 0.8% of Peninsular Malaysia's inhabitants, though not all speak Aslian languages due to shifts toward Malayic varieties among some Proto-Malay subgroups.[7] [8] The Negrito (Semang) groups, speakers of Northern Aslian languages, include tribes such as the Batek, Jahai, Mendriq, Kensiu, Kentaq, and Lanoh, characterized by traditionally nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles in forested interiors. Their populations remain small, with the Batek estimated at around 1,500 individuals across Pahang, Terengganu, and Kelantan states as of recent surveys. Overall Negrito numbers constitute a minor fraction of the Orang Asli total, likely under 10,000, reflecting historical marginalization and assimilation pressures. In Thailand, Maniq (a Semang-related group) number 300–400 speakers.[9] [10] [5] Senoi groups, the largest ethnic division and primary speakers of Central Aslian languages like Semai and Temiar, account for over half of Orang Asli, with Semai populations estimated at 44,000–59,500 and Temiar at 19,000–35,000 based on varying ethnographic and census-derived figures. Other Senoi subgroups, such as Jah Hut and Che Wong, have middle-sized communities. These groups often practice swidden agriculture and maintain semi-sedentary villages in highland areas of Perak and Pahang.[11] [12] Proto-Malay groups, associated with Southern Aslian languages including Semelai, Mah Meri, Semaq Beri, and Temuan, exhibit more coastal and riverine adaptations, with some bilingualism in Malay dialects reducing pure Aslian speaker counts. Their populations are smaller than Senoi, comprising middle to small community sizes without precise recent aggregates exceeding 20,000–30,000 collectively. Aslian speakers overall number at least 100,000–113,000, roughly two-thirds of Orang Asli, per linguistic assessments adjusting for language shift.[4] [5]| Ethnic Category | Key Subgroups and Languages | Approximate Population Estimate | Source Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negrito (Semang) | Batek, Jahai, Maniq (Northern Aslian) | <10,000 (Malaysia); 300–400 (Thailand) | 2010–2022 [5] [9] |

| Senoi | Semai, Temiar (Central Aslian) | 60,000–90,000 | 2003–present [11] [12] |

| Proto-Malay | Semelai, Mah Meri (Southern Aslian) | 20,000–30,000 (subset Aslian) | 2008–2013 [5] [4] |

Regional Variations and Dialects

The Aslian languages display regional variations aligned with their primary subgroups—Northern Aslian (Jahaic), Central Aslian (Senoic), Jah Hut, and Southern Aslian (Semelaic)—spanning Peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand.[5] Northern Aslian varieties, including Jahai, Batek, Kensiw, Kintaq, Menriq, Ceq Wong, and Maniq, occupy northern regions from Kedah and Perak in Malaysia to Yala and Satun provinces in Thailand, with approximately 300–400 Maniq speakers in Thailand.[5] These form a partial dialect continuum disrupted by migrations, evidenced by lexical similarities such as 76.6% between Menriq Rual and other Menriq varieties, below the 86% threshold for distinct languages.[13] Phonological distinctions include Menriq Rual's uvular fricative [ʁ] for /r/ and archaic first-person singular pronoun /ʔiɲ/, shared with Ceq Wong and Maniq.[13] Central Aslian languages, such as Temiar and Semai, predominate in central Malaysia's Perak, Pahang, and Kelantan states, with Temiar serving as a historical lingua franca among speakers.[5] Semai exhibits over 40 dialects, one per village, fostering unique regional flavors shaped by barriers like the Perak-Pahang mountain range; these divide into Northern, Central, and Southern Semai groups.[14][5] Temiar features northern and southern dialects, with variations in final stops (retaining voiced/voiceless distinctions in some) and morphological elements like a unique middle-voice affix -a-.[5] Lanoh, another Central Aslian language, includes dialects like Yir and Jengjeng.[5] Jah Hut, treated as an isolate branch, is confined to central Pahang in Malaysia, with minimal documented dialectal diversity.[1] Southern Aslian languages, encompassing Semelai, Semaq Beri, Mah Meri, and Temoq, are distributed in southern Peninsular Malaysia, particularly Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, and Johor, exhibiting elevated Malay lexical borrowing (e.g., 25% in Mah Meri) but limited internal dialectal fragmentation relative to Central Aslian.[5] Overall, Aslian speakers number around 100,000, predominantly Orang Asli in Malaysia, with variations often tied to ecological adaptations and contact with Malay.[5]Prehistory and Origins

Archaeological and Genetic Evidence

Archaeological evidence points to the Hoabinhian technocomplex as a key correlate for the prehistoric subsistence patterns of early Aslian-speaking populations in the Malay Peninsula. Characterized by unifacial pebble tools, flakes, and cobble choppers, Hoabinhian sites such as Gua Cha in Kelantan and other caves in Perak and Pahang yield dates spanning approximately 12,000 to 2,000 years before present, reflecting late Pleistocene to mid-Holocene hunter-gatherer adaptations in forested environments. These assemblages, lacking polished stone tools or ceramics indicative of Neolithic farming, align with the foraging lifeways historically documented among Northern Aslian-speaking Negrito groups like the Semang, suggesting cultural continuity from indigenous Peninsula foragers rather than later migrants.[15] Genetic studies corroborate this link, demonstrating that Aslian speakers, especially Negrito subgroups such as the Jehai and Kensiu, carry significant Hoabinhian-related ancestry, often exceeding 50% in some Northern Aslian populations. Whole-genome sequencing reveals shared genetic drift between these groups and ancient Hoabinhian individuals from sites like Spirit Cave in Laos, indicating descent from deeply diverged East Asian hunter-gatherer lineages predating Neolithic expansions.[16][17] Senoi Aslian speakers, associated with Central and Southern branches, exhibit greater admixture from East Asian-related Neolithic sources, modeled as approximately 30-50% Hoabinhian ancestry combined with farmer components arriving around 4,000-5,000 years ago, consistent with broader Austroasiatic dispersals but preserving relict Peninsula hunter-gatherer signals.[17] This admixture pattern underscores Aslian groups as genetic reservoirs of pre-Neolithic Peninsula diversity, with minimal affinity to Andamanese isolates despite superficial morphological parallels in some Negritos.[18]Migration Hypotheses and Debates

The primary migration hypothesis posits that Aslian-speaking populations entered the Malay Peninsula from mainland Southeast Asia during the Early Neolithic period, approximately 4,300 years before present (BP), coinciding with the introduction of agriculture.[1] This influx likely involved a gradual "trickle" of migrants into existing small-scale forager communities rather than large-scale population replacement, facilitating linguistic diffusion down the western peninsula.[1] Bayesian phylogeographic modeling of lexical data supports this, estimating the Proto-Aslian homeland in the central peninsula near Gunung Benom, with subsequent branching: an initial binary split separating Southern Aslian from other branches around 4,000 BP, followed by diversification of Northern, Central, and Jah Hut groups in the Late Neolithic to Metal Age (3,000–2,000 BP).[1] Genetic evidence aligns with this linguistic timeline but highlights admixture dynamics among Aslian subgroups. Negrito groups (speakers of Northern Aslian Semang languages) represent Southeast Asia's earliest inhabitants, with basal ancestry dating to 50,000–60,000 years ago, yet they exhibit language shift toward Aslian, suggesting adoption from incoming Austroasiatic agriculturalists.[19] Senoi populations, associated with Central Aslian, show admixture between local hunter-gatherers and Indochinese-derived Austroasiatic migrants around 5,500 years ago, marked by haplogroups like F1a1a and N9a6a, indicating a southward expansion of farming groups that integrated with indigenous foragers.[19] This supports a model where Aslian languages spread via cultural and linguistic assimilation rather than demographic dominance, with Negritos retaining ancient genetic profiles despite adopting Aslian speech.[19][1] Debates center on the precise entry route, pre-Aslian linguistic landscape, and interactions with contemporaneous expansions. While linguistic diffusion models favor a western coastal pathway from the Kra Isthmus southward, some genetic data imply multiple waves, including earlier Southern Route migrations (~65,000 years ago) predating Austroasiatic arrival.[1][19] Controversy persists over whether Aslian diversification reflects uniform cladogenesis or significant language shifts among foragers, challenging earlier tripartite split models and emphasizing branch-specific diffusion rates.[1] Additionally, Aslian speakers' adoption of Austronesian cultural elements, such as material culture and swidden practices, has been attributed to dominance by proto-Malay migrants from Borneo around 3,000–4,000 years ago, postdating initial Aslian settlement and prompting questions about substrate influences or bidirectional borrowing.[1] These hypotheses integrate linguistics, archaeology, and genetics but remain tentative due to sparse pre-Neolithic data in the peninsula.Classification Within Austroasiatic

Internal Subgrouping

The Aslian languages are classified into four primary internal subgroups: Northern Aslian (also termed Jahaic or Semang), Central Aslian (Senoic), Southern Aslian (Semelaic), and Jah Hut as a distinct branch.[1][20] This quadripartite division, proposed by Diffloth and Zide (1992) and supported by computational phylogenetic analyses, reflects lexical, phonological, and morphological divergences among the approximately 18-20 Aslian varieties spoken by Orang Asli groups in Peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand.[1] Northern Aslian encompasses languages spoken by Negrito groups in northern Peninsular Malaysia, including Maniq (Kensiu, Kentaq, Ten'edn), Batek (Batek, Jahai, Minriq, Mintil), and Cheq Wong, with phylogenetic evidence indicating subclades such as Menraq-Batek and Maniq.[20] These languages exhibit conservative retentions like sesquisyllabic word structures and are estimated to number around 5,000 speakers collectively.[1] Central Aslian, or Senoic, includes Temiar, Semai, Lanoh, Sabüm, and Semnam, primarily spoken in the central highlands of Perak, Pahang, and Kelantan by Senoi populations totaling over 100,000 speakers.[1] This subgroup shows innovations in vowel harmony and ablaut patterns, distinguishing it from northern varieties.[20] Southern Aslian, known as Semelaic, comprises Mah Meri (Besisi), Semelai, Temoq, and Semaq Beri, spoken by southern Orang Asli in Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, and Johor, with smaller speaker communities under 10,000.[1] These languages feature marked phonological reductions and are coordinate with the other branches in divergence time estimates from Bayesian models.[20] Jah Hut stands as an isolate subgroup, spoken by about 3,000 people in central Pahang, characterized by unique morphological complexities like infixation not prominently shared with other Aslian branches, though phylogenetic support for its separation is moderate at 45% posterior probability.[1][20] Earlier classifications by Benjamin (1976) and Diffloth (1975, 1979) emphasized a tripartite structure (Northern, Central, Southern) prior to elevating Jah Hut.[20]Relation to Broader Austroasiatic Family

The Aslian languages form a distinct subgroup within the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic language family, which encompasses over 150 languages across South and Southeast Asia.[21] This positioning is supported by shared phonological features, such as sesquisyllabic word structures and specific consonant correspondences, traceable to Proto-Austroasiatic reconstructions.[22] Lexical cognates, including forms for basic vocabulary like body parts and numerals, further affirm Aslian's genetic ties to the family, with etymologies reconstructed across Austroasiatic subgroups.[4] Within the broader Austroasiatic phylum, divided into the northern Munda languages of India and the southern Nuclear Austroasiatic (including Mon-Khmer), Aslian represents the southernmost extension, primarily confined to the Malay Peninsula.[5] Comparative studies highlight Aslian's closest relations to the Monic subgroup (encompassing Mon and related languages) and potentially the Nicobarese languages, evidenced by high cognate percentages in core vocabulary and shared morphological innovations like prefixal derivations.[4] For instance, cognates such as rəwaay for "head-soul" and -həəm for "breathe" link Aslian forms to Monic and Nicobarese equivalents.[4] Computational phylogenetic analyses of lexical datasets from 26 Aslian languages, using Bayesian methods on Swadesh lists, confirm Aslian's internal coherence and its rooting within Austroasiatic, with divergence estimates placing proto-Aslian around 4,000–3,500 years ago.[23] These models account for rate variation and borrowing, revealing shared innovations with Mon-Khmer branches but distinct areal influences from Austronesian contact in the peninsula.[1] While the exact internal positioning of Aslian relative to other Mon-Khmer subgroups remains debated due to sparse data from some languages, the consensus upholds its integral role in Austroasiatic reconstructions, contributing unique southern reflexes to proto-forms.[6]Alternative Classifications and Controversies

While Aslian languages are conventionally recognized as a primary branch of the Austroasiatic family, alternative proposals have sought to align them more closely with other southern or peripheral branches. Gérard Diffloth's 2005 classification posits Aslian within a "southern" grouping that also encompasses Monic and Nicobarese languages, based on shared phonological and morphological traits such as complex vowel systems and sesquisyllabic word structures.[24] This contrasts with earlier lexicostatistical assessments emphasizing Aslian's isolation due to low shared vocabulary (often below 20% cognacy) with core Mon-Khmer branches like Katuic or Bahnaric.[25] More recent scholarship by Paul Sidwell refines this by proposing a specific Aslian-Nicobarese clade, excluding Monic, supported by comparative evidence of innovations in pronominal systems and verb morphology; for instance, parallel developments in alienable possession marking distinguish this pair from mainland Austroasiatic groups.[26] Sidwell's 2022 analysis of Nicobarese internal structure reinforces this distant genetic link to Aslian, attributing geographic separation—spanning the Andaman Sea—to divergent evolution rather than independent origins.[26] These proposals remain contested, as Nicobarese exhibits higher vowel phoneme counts (up to 20 in some varieties) atypical of Aslian, potentially reflecting substrate influences from pre-Austroasiatic Andamanese languages.[26] Controversies also stem from Aslian's typological profile, including a heavy word-final accent and iambic rhythm, which diverge from the predominantly even stress patterns in many northern Austroasiatic languages like Khmuic or Vietic.[4] Thomas Sebeok highlighted such disparities in 1942, arguing they undermine uniform family coherence and suggesting possible areal convergence with Austronesian neighbors over deep genetic unity.[25] Sidwell's 2013 review echoes this caution, noting that Aslian's peripheral status and limited documentation (with some languages known from fewer than 1,000 speakers as of 2010) complicate reconstructions, though core etyma like numerals and body-part terms affirm Austroasiatic affiliation.[21] Empirical support for alternatives relies heavily on Sidwell's etymological database of over 500 proto-Austroasiatic forms, yet critics argue insufficient shared innovations to elevate Aslian-Nicobarese beyond coordinate branches.[22]Linguistic Reconstruction

Proto-Aslian Phonology and Lexicon

The reconstruction of Proto-Aslian phonology relies on the comparative method applied to daughter languages, primarily advanced by Timothy Phillips in his 2012 Ph.D. thesis at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Phillips posits a phonological system with sesquisyllabic syllable structures typical of Austroasiatic proto-languages, featuring minor syllables often reduced to schwa (*ə) or nasal prefixes. The consonant inventory includes stops at bilabial (*p, *b), alveolar (*t, *d), palatal (*c/*ɟ, *ɟ), velar (*k, *g), and glottal (*ʔ) positions; nasals (*m, *n, *ŋ); fricatives (*s, *h); lateral (*l); rhotic (*r); and approximants (*w, *j). Evidence for these comes from regular correspondences, such as *k- > k in Northern Aslian but occasional affrication in Southern branches.[27] [3] The vowel system, subject to ongoing refinement, includes short and long monophthongs: high (*i, *ɨ, *u, ɯ), mid (*e, *ə, o), and low (a), with length contrasts preserved in conservative varieties like Jahai and Temiar. Phillips' forms suggest diphthongs or offglides in some rimes, such as *-ɛw or *-aam, though Sidwell (2023) argues for a more conservative vocalism with fewer mergers, emphasizing areal influences on vowel shifts post-dispersal. Preplosion (nasal + stop sequences realized as pre-stopped nasals in reflexes) is reconstructed for certain codas, reflecting inherited Austroasiatic traits but innovated in Aslian subgroups.[27] [28] Lexical reconstruction yields over 280 etyma, focusing on core vocabulary resistant to borrowing. Phillips' dataset includes body parts (ɟuŋ 'leg/foot', kətɯɯʔ 'skin'), kinship and numerals (səmaaʔ 'person/human', (m,n)uay 'one'), and environmental terms (wiɛl 'left', mahaam 'blood'). These forms demonstrate regular sound changes, such as *ə > a in open syllables in Southern Aslian. Sidwell (2021) highlights Aslian-specific innovations, including shared terms for local flora like bamboo shoots and insects, absent in other Austroasiatic branches, supporting internal coherence and divergence around 4,000–5,000 years ago.[27] [22]| Category | Example Proto-Aslian Forms |

|---|---|

| Body parts | ɟuŋ 'leg/foot', kətɯɯʔ 'skin', mahaam 'blood' |

| Numerals/People | (m,n)uay 'one', səmaaʔ 'person' |

| Other | wiɛl 'left' |

Comparative Method Applications

The comparative method has been applied to Aslian languages to identify regular sound correspondences, reconstruct proto-forms, and delineate internal genetic subgroupings. Early efforts, such as those by Wilhelm Schmidt in the early 20th century, relied on lexical comparisons to affirm Aslian's place within Austroasiatic, though systematic phonological reconstruction lagged.[24] Gérard Diffloth advanced this in the 1960s–1970s by comparing vocabularies across Aslian varieties, proposing sound changes like the development of implosive stops and identifying shared innovations that support a primary split between Northern Aslian (Semang) and Southern Aslian (Saki).[5] Timothy Phillips' 2012 reconstruction of Proto-Aslian exemplifies rigorous application of the method, drawing on cognate sets from over 20 Aslian languages to posit phonological inventories including 20–25 consonants and a vowel system with length distinctions.[14] He established correspondences, such as *p > ph in certain environments across subgroups, and reconstructed approximately 289 etyma, revealing lexical innovations unique to Aslian, like terms for local flora and fauna.[22] These efforts highlight challenges in Aslian reconstruction, including sparse documentation and dialect continua, necessitating careful selection of conservative forms to avoid borrowing influences from Austronesian or Malay.[5] Subgrouping applications have utilized shared derived traits identified via the comparative method, confirming clades like Maniq-Jahai within Northern Aslian through consistent lexical and phonological matches not found in broader Austroasiatic.[24] Paul Sidwell's comparative work on Mon-Khmer further contextualizes Aslian innovations, such as sesquisyllabic roots, as retentions rather than developments, aiding in distinguishing inherited from contact-induced features.[22] Ongoing debates concern the depth of divergence, with some reconstructions suggesting Proto-Aslian dates to around 4,000–5,000 years ago based on calibrated lexical retention rates.[29]Phonological Characteristics

Consonant Inventories and Syllable Patterns

Aslian languages feature consonant inventories that align with broader Austroasiatic patterns, typically comprising 15 to 25 phonemes with stops articulated at bilabial, alveolar, palatal, velar, and glottal places of articulation, often contrasting voiced and voiceless series (e.g., /p b/, /t d/, /c ɟ/, /k ʔ/).[30][31] Nasals occur at bilabial (/m/), alveolar (/n/), palatal (/ɲ/), and velar (/ŋ/) positions, while liquids (/l/, /r/) and glides (/w/, /j/) provide additional contrasts; fricatives like /s/ and /h/ are present in select languages, especially Northern Aslian varieties such as Jahai.[4][31]| Place/Manner | Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives (voiceless) | p | t | c | k | ʔ |

| Plosives (voiced) | b | d | ɟ | (g) | |

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Liquids | l, r | ||||

| Glides | w | j | |||

| Fricatives | (s) | h |

Vowel Systems and Prosody

Aslian languages exhibit rich and complex vowel systems, typically featuring a minimum of nine distinct places of articulation, with contrasts in height (at least three degrees, often four or five), orality versus nasality, and length (short versus long).[5][30] Diphthongs and vowel harmony are also common, contributing to large inventories; for instance, Northern Temiar distinguishes up to 30 vocalic nuclei through these parameters, while Semnam has 36 phonemic nuclei.[4][33] In Jahai, a Northern Aslian language, the system includes three heights (/i, e, ɛ/ front; /ɨ, ə, a/ central; /u, o, ɔ/ back) with additional nasal and long variants, yielding extensive minimal pairs.[31] Specific examples illustrate these distinctions: Temiar contrasts vowels like /i/ and /ɛ/ in pairs such as tiiˀ "yet" versus tɛɛˀ "earlier today," with nasality and length further differentiating forms across the inventory /i, ʉ, u, e, ə, o, ɛ, a, ɔ/.[4] Southern Aslian languages like Mah Meri incorporate register contrasts alongside nine basic vowels, where Register 1 features clear, tense voicing with lower fundamental frequency (average onset 120.6 Hz) and Register 2 shows breathier, laxer quality with higher f0 (133.3 Hz onset), though duration differences are inconsistent (Register 1: 254 ms average; Register 2: 230 ms).[34] Prosodically, Aslian languages generally lack full tonal systems but display stress-based patterns, often iambic with emphasis on word-final syllables, contrasting with penultimate stress in contact languages like Malay; words typically begin with a consonant (or glottal stop) and end with unexploded stops.[4] However, Northern Aslian subgroups, such as Jahai and Kensiw, show incipient tonal activity, with phonetic evidence of pitch contrasts emerging from earlier voice qualities or stress, marking a departure from the family's predominantly non-tonal profile.[35] Rhythm tends toward sesquisyllabic structures in many varieties, with primary stress on major (often initial) syllables reinforcing the phonological word.[5]Morphological and Syntactic Features

Affixation and Reduplication Processes

Aslian languages predominantly utilize prefixation and infixation for morphological derivation and inflection, with suffixes being rare or absent in most branches. Prefixes often mark causative, reciprocal, or distributive functions, while infixes such as -r-, -n-, and -a- encode causatives, nominalization, and instrumental roles, respectively; these patterns are reconstructed to Proto-Aslian and persist in languages like Temiar and Jahai.[4] Borrowing of affixes from Austronesian languages, particularly Malay, is widespread, introducing novel prefixes for voice or aspect in verbal paradigms, as documented in Semai.[36] Reduplication functions as a core derivational and inflectional strategy, expressing iteration, continuity, intensification, and plurality; it often interacts with affixation to yield hybrid forms. In Temiar, continuative aspect employs prefixal reduplication of the initial syllable or consonant, described as a-templatic due to its lack of fixed prosodic shape, applying to both monosyllabic and disyllabic roots.[37] Semai expressives feature suffixed partial reduplication of the major syllable, sometimes reducing to bare consonants while retaining historical root segments lost in non-reduplicated forms, highlighting reduplication's role in phonological archaism.[38][39] A distinctive process, termed incopyfixation, combines infixation with partial reduplication by copying the root's coda into the infix slot, yielding forms like Jahai bənuk 'to swell' → bən-nuk 'swollen'; this is widespread across Northern, Central, and Southern Aslian subgroups, serving nominalizing or resultative functions and reflecting ancient morphological layering.[4] Reduplicants frequently exhibit "emergence of the unmarked," simplifying syllable structure relative to the base (e.g., avoiding complex codas), as analyzed in comparative Aslian data.[40] These processes underscore Aslian's non-concatenative morphology, where reduplication preserves etymological transparency amid sesquisyllabic roots.[41]Word Order, Voice, and Deixis

Aslian languages predominantly follow a subject-verb-object (SVO) word order, characteristic of verb-medial syntax in mainland Austroasiatic branches.[4] Prepositional phrases precede verbs, while post-head modifiers—including determiners, possessors, adjectives, and relative clauses—follow nominal heads, as in Mah Meri dək naleˀ ('house old') or Semelai smaˀ ma-dəmdəm ('person REL-lie.down').[4] Word order permits pragmatic permutations, supported by optional case or role markers such as agentive naˀ in Jah Hut or nominative ˀi- in Temiar, which disambiguate non-canonical arrangements.[4] Voice systems in Aslian languages employ derivational morphology, including affixes and reduplication, to encode distinctions like middle and causative voices. In Temiar, middle voice is realized through partial reduplication, as in gagəl from gəl ('roll'), while causatives involve prefixes like tər- in trgəl ('cause to roll').[4] These mechanisms align with broader Austroasiatic patterns of valency adjustment but show substrate influences from areal contact, without the symmetrical voice typical of Austronesian languages. Passive constructions, where attested, often rely on contextual inference or periphrastic means rather than dedicated morphology. Deictic systems vary across Aslian subgroups but emphasize precision, particularly in Northern Aslian (Senoic) languages through elaborate pronominal paradigms that encode spatial and social relations. Jahai demonstratives incorporate perceptual and accessibility contrasts, such as ˀəh for speaker-accessible items versus ˀaniˀ for inaccessible ones, extending beyond proximal-distal binaries to include visibility or sensory immediacy.[4] This reflects an adaptive encoding of environmental navigation in foraging contexts, with directionals and orientation terms further enriching spatial deixis in languages like Jahai.[4]Lexical and Semantic Traits

Core Vocabulary and Semantic Fields

Core vocabulary in Aslian languages consists primarily of monosyllabic or sesquisyllabic roots for basic concepts, with high retention of Proto-Aslian forms in domains such as numerals, body parts, and environmental terms, reflecting the family's deep-time divergence within Austroasiatic. Geoffrey Benjamin's lexicostatistical analysis, employing a modified Swadesh list of 146 items tailored to Aslian contexts (including culturally relevant terms like those for forest flora and fauna), demonstrated lexical similarities exceeding 20% across subgroups, supporting genetic unity despite areal influences.[42] Loan rates from Malay into basic vocabulary remain low in hunter-gatherer Northern Aslian varieties (under 10% for items like 'hand' or 'two'), but rise in sedentary Central and Southern groups due to prolonged contact.[43] Numeral systems provide a key semantic field, with Proto-Aslian reconstructions evident in shared morphemes: for instance, elements like *sa- ('one') and *pa- ('four') recur in South Aslian forms, while Northern varieties innovate with click-augmented counters for small quantities in foraging contexts. Gérard Diffloth's morphological comparison reveals pan-Aslian patterns, such as prefixal elements in higher numerals (e.g., *tuə- 'seven' derivatives), underscoring pre-contact coherence before Austronesian and Malay overlays altered teen numerals in peripheral languages. Specific attestations include Semai *naːr ('one') and *pɛd ('two'), cognate across Central Aslian, with minimal borrowing in core counts up to ten.[44] Body part terminology forms another conserved field, often inalienably possessed and extended metaphorically to spatial relations or classifiers; in Jahai (Northern Aslian), terms like *kəʔəp ('head') and *ʔaləʔ ('hand') derive from Proto-Aslian roots, with semantic specificity distinguishing, for example, the crown from the face—unlike broader Mon-Khmer equivalents.[45] These terms exhibit low replaceability, with Jahai speakers restricting 'head' to osseous structures in experimental tasks, reflecting a perceptual-semantic prototype conserved across Aslian despite substrate pressures. Proto-Aslian *m-at ('eye') cognates appear widely, linking to verbs of seeing and informing classifiers for round objects.[46] Kinship semantics emphasize generation and moiety over descent polarity, with core terms showing Aslian-wide cognates like *ʔapəʔ ('father') and *iːʔ ('mother'), compounded for collaterals; affinal avoidance registers in languages like Semai substitute pronouns with kin-derived classifiers, preserving Proto-Aslian *kənəw ('spouse') roots amid simple gender-neutral spouse terms. Robert Parkin's cognate analysis identifies over 30 shared kin roots, with loans confined to peripheral roles like 'in-law,' indicating endogenous development of Dravidian-like cross-cousin distinctions in Central Aslian.[47] Environmental fields, such as flora-fauna, dominate non-human animacy, with Proto-Aslian *sŋəʔ ('animal') and subgroup innovations for tubers (*kəlab 'yam'), adapted to foraging lifestyles and resistant to exonyms.[48] Timothy Phillips' Proto-Aslian lexicon reconstructs over 200 basic items, prioritizing these fields for subgrouping stability.[1]Contact-Induced Changes and Borrowings

Aslian languages display extensive lexical borrowings from Malay, reflecting centuries of trade, labor, and cultural exchange with Austronesian-speaking populations in the Malay Peninsula.[5] Borrowing rates vary by branch and subgroup, with Southern Aslian languages showing particularly high integration—such as 25% in Mah Meri and 23% in Semelai—while Central Aslian languages like Temiar exhibit lower rates around 2%.[5] These loans often pertain to domains of Malay cultural dominance, including agriculture, administration, and material culture, though core vocabulary tends to retain native Aslian roots. Phonological adaptations of Malay loanwords occur to align with Aslian syllable structures and phonemic inventories, sometimes deliberately marking them as foreign through additions like velar fricatives. In Temiar, for instance, kəbun (garden) becomes kəbut, raŋcaŋ (plan) yields raŋcak, naŋka (jackfruit) shifts to daŋkaaʔ, and ɲamoʔ (mosquito) to jamoʔ.[5] Northern Aslian varieties in Thailand incorporate aspirated stops from Thai loans, representing an areal phonological innovation absent in more isolated Aslian groups.[5] Beyond recent Malayic influence, Aslian lexicons preserve older borrowings from pre-Malay Austronesian sources, including Bornean varieties (e.g., beteŋ for belly, seput for blowpipe, asu for dog) and Chamic languages (e.g., liman for elephant, abãt for cloth).[49] Additional layers include loans from Acehnese (telas for finished, awe for rattan) and secondary contact with Mon and Khmer.[49] These multilayered borrowings underscore a "palimpsest" of historical contacts, with Austronesian elements influencing not only lexicon but also cultural practices like musical instruments (tube-zithers, Jews' harps), without displacing Aslian grammatical cores.[49] In Ceq Wong, a Northern Aslian language, loans likely derive from proximate Austronesian dialects like Temuan or via Malay intermediaries, integrating into the native phonological system.[50] Overall, contact-induced changes remain predominantly lexical, with limited evidence of syntactic calquing or profound structural shifts.[5]Sociolinguistic Dynamics

Language Contact and External Influences

The Aslian languages, spoken primarily by indigenous groups in Peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand, have undergone extensive contact with neighboring language families, resulting in phonological, lexical, and structural borrowings. Dominant external influences stem from Malay (an Austronesian language) and Thai (a Tai-Kadai language), reflecting historical trade, migration, and assimilation pressures on Aslian-speaking communities. These contacts have introduced loanwords, especially in domains like agriculture, administration, and material culture, with Southern Aslian varieties exhibiting particularly high rates of Malay lexical integration due to prolonged socioeconomic integration with Malay-speaking populations.[5] In Southern Aslian languages such as Semelai and Ceq Wong, Malay borrowings constitute a substantial portion of the modern lexicon, often adapting to native phonological patterns while filling gaps in terminology for introduced concepts or goods. For instance, Ceq Wong displays elevated loan rates from Proto-Southern Aslian neighbors via intermediary contact, but direct Malay influx predominates in everyday vocabulary, correlating with speakers' historical roles in plantation economies and urban proximity. This borrowing pattern underscores asymmetrical contact dynamics, where Aslian varieties absorb terms without reciprocal influence on Malay.[50] Northern Aslian languages, including Jahai and Maniq, show phonological adaptations from Thai contact, such as the development or reinforcement of aspirated stops, atypical for core Austroasiatic inventories but aligned with Thai areal features in border regions. Lexical evidence also points to Thai loanwords in subsistence and environmental terms, though Malay remains a pervasive superstrate across subgroups due to Malaysian national policies promoting bilingualism. These shifts highlight gradient external pressures, with isolation in forested interiors mitigating but not eliminating diffusion.[51][52] Historical layers of contact reveal deeper influences, including lexical traces from Mon (a distantly related Austroasiatic branch) and possibly extinct populations, forming a "palimpsest" of borrowings that predate modern dominant languages. Evidence of early Austronesian contact appears in Aslian core vocabulary and cultural lexicon, suggesting prehistoric interactions that contributed to hybrid material practices despite genetic Austroasiatic affiliation. Such ancient substrates complicate phylogenetic reconstruction, as contact-induced changes obscure proto-forms, yet computational analyses confirm diffusion over inheritance in select semantic fields.[49]Endangerment Factors and Extinction Risks

Aslian languages collectively face significant endangerment, with approximately half of the roughly 20 languages no longer being acquired by children, placing them on track for extinction within the current generation.[4] Total speaker numbers stand at around 100,000, representing two-thirds of the Orang Asli population of about 170,000 as of 2013, though individual languages often have far fewer speakers, amplifying vulnerability.[4] Languages such as Sabüm and Lanoh Yir became extinct in the 1970s, while others like Mintil (<40 speakers) and Chewong (200 speakers) are critically endangered.[53] Primary factors include failed intergenerational transmission, driven by younger Orang Asli preferring Malay for socioeconomic advancement, education, and intermarriage.[4] Urbanization, mass media exposure, and shifts from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to agriculture further erode usage, as dominant languages like Malay gain prestige through state institutions.[4] Government policies promoting assimilation and religious conversion to Islam exacerbate this, restricting traditional practices and encouraging language shift.[53] Environmental pressures compound risks, with commercial logging and deforestation fragmenting communities and disrupting ecosystems tied to Aslian cultural practices, such as shifting cultivation.[53] In southern Thailand and Peninsular Malaysia, some languages remain viable short-term but face uncertain futures without intervention, as speakers increasingly adopt regional lingua francas.[54] Overall extinction risks are high for moribund varieties, where elderly speakers dominate and no revitalization efforts sufficiently counter shift dynamics.[4]| Language | Estimated Speakers | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Mintil | <40 | Critically endangered[53] |

| Chewong | 200 | Endangered[53] |

| Temoq | 350 | Endangered[53] |