Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hearing

View on WikipediaThis article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (May 2019) |

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium.[1] The academic field concerned with hearing is auditory science.

Sound may be heard through solid, liquid, or gaseous matter.[2] It is one of the traditional five senses. Partial or total inability to hear is called hearing loss.

In humans and other vertebrates, hearing is performed primarily by the auditory system: mechanical waves, known as vibrations, are detected by the ear and transduced into nerve impulses that are perceived by the brain (primarily in the temporal lobe). Like touch, audition requires sensitivity to the movement of molecules in the world outside the organism. Both hearing and touch are types of mechanosensation.[3][4]

Hearing mechanism

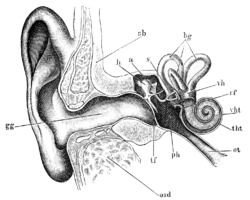

[edit]There are three main components of the human auditory system: the outer ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear.

Outer ear

[edit]

The outer ear includes the pinna, the visible part of the ear, as well as the ear canal, which terminates at the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane. The pinna serves to focus sound waves through the ear canal toward the eardrum. Because of the asymmetrical character of the outer ear of most mammals, sound is filtered differently on its way into the ear depending on the location of its origin. This gives these animals the ability to localize sound vertically. The eardrum is an airtight membrane, and when sound waves arrive there, they cause it to vibrate following the waveform of the sound. Cerumen (ear wax) is produced by ceruminous and sebaceous glands in the skin of the human ear canal, protecting the ear canal and tympanic membrane from physical damage and microbial invasion.[5]

Middle ear

[edit]

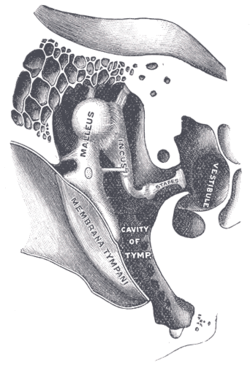

The middle ear consists of a small air-filled chamber that is located medial to the eardrum. Within this chamber are the three smallest bones in the body, known collectively as the ossicles which include the malleus, incus, and stapes (also known as the hammer, anvil, and stirrup, respectively). They aid in the transmission of the vibrations from the eardrum into the inner ear, the cochlea. The purpose of the middle ear ossicles is to overcome the impedance mismatch between air waves and cochlear waves, by providing impedance matching.

Also located in the middle ear are the stapedius muscle and tensor tympani muscle, which protect the hearing mechanism through a stiffening reflex. The stapes transmits sound waves to the inner ear through the oval window, a flexible membrane separating the air-filled middle ear from the fluid-filled inner ear. The round window, another flexible membrane, allows for the smooth displacement of the inner ear fluid caused by the entering sound waves.

Inner ear

[edit]

The inner ear consists of the cochlea, which is a spiral-shaped, fluid-filled tube. It is divided lengthwise by the organ of Corti, which is the main organ of mechanical to neural transduction. Inside the organ of Corti is the basilar membrane, a structure that vibrates when waves from the middle ear propagate through the cochlear fluid – endolymph. The basilar membrane is tonotopic, so that each frequency has a characteristic place of resonance along it. Characteristic frequencies are high at the basal entrance to the cochlea, and low at the apex. Basilar membrane motion causes depolarization of the hair cells, specialized auditory receptors located within the organ of Corti.[6] While the hair cells do not produce action potentials themselves, they release neurotransmitter at synapses with the fibers of the auditory nerve, which does produce action potentials. In this way, the patterns of oscillations on the basilar membrane are converted to spatiotemporal patterns of firings which transmit information about the sound to the brainstem.[7]

Neuronal

[edit]

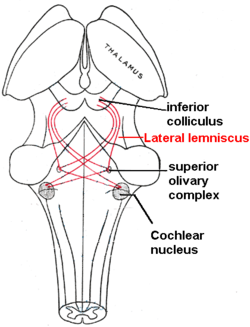

The sound information from the cochlea travels via the auditory nerve to the cochlear nucleus in the brainstem. From there, the signals are projected to the inferior colliculus in the midbrain tectum. The inferior colliculus integrates auditory input with limited input from other parts of the brain and is involved in subconscious reflexes such as the auditory startle response.

The inferior colliculus in turn projects to the medial geniculate nucleus, a part of the thalamus where sound information is relayed to the primary auditory cortex in the temporal lobe. Sound is believed to first become consciously experienced at the primary auditory cortex. Around the primary auditory cortex lies Wernicke's area, a cortical area involved in interpreting sounds that is necessary to understand spoken words.

Disturbances (such as stroke or trauma) at any of these levels can cause hearing problems, especially if the disturbance is bilateral. In some instances it can also lead to auditory hallucinations or more complex difficulties in perceiving sound.

Hearing tests

[edit]Hearing can be measured by behavioral tests using an audiometer. Electrophysiological tests of hearing can provide accurate measurements of hearing thresholds even in unconscious subjects. Such tests include auditory brainstem evoked potentials (ABR), otoacoustic emissions (OAE) and electrocochleography (ECochG). Technical advances in these tests have allowed hearing screening for infants to become widespread.

Hearing can be measured by mobile applications which includes audiological hearing test function or hearing aid application. These applications allow the user to measure hearing thresholds at different frequencies (audiogram). Despite possible errors in measurements, hearing loss can be detected.[8][9]

Hearing loss

[edit]There are several different types of hearing loss: conductive hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss and mixed types. Recently, the term of Aural Diversity has come into greater use, to communicate hearing loss and differences in a less negatively-associated term.

There are defined degrees of hearing loss:[10][11]

- Mild hearing loss - People with mild hearing loss have difficulties keeping up with conversations, especially in noisy surroundings. The most quiet sounds that people with mild hearing loss can hear with their better ear are between 25 and 40 dB HL.

- Moderate hearing loss - People with moderate hearing loss have difficulty keeping up with conversations when they are not using a hearing aid. On average, the most quiet sounds heard by people with moderate hearing loss with their better ear are between 40 and 70 dB HL.

- Severe hearing loss - People with severe hearing loss depend on powerful hearing aid. However, they often rely on lip-reading even when they are using hearing aids. The most quiet sounds heard by people with severe hearing loss with their better ear are between 70 and 95 dB HL.

- Profound hearing loss - People with profound hearing loss are very hard of hearing and they mostly rely on lip-reading and sign language. The most quiet sounds heard by people with profound hearing loss with their better ear are from 95 dB HL or more.

Causes

[edit]- Heredity

- Congenital conditions

- Presbycusis

- Acquired

- Noise-induced hearing loss

- Ototoxic drugs and chemicals

- Infection

Prevention

[edit]Hearing protection is the use of devices designed to prevent noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), a type of post-lingual hearing impairment. The various means used to prevent hearing loss generally focus on reducing the levels of noise to which people are exposed. One way this is done is through environmental modifications such as acoustic quieting, which may be achieved with as basic a measure as lining a room with curtains, or as complex a measure as employing an anechoic chamber, which absorbs nearly all sound. Another means is the use of devices such as earplugs, which are inserted into the ear canal to block noise, or earmuffs, objects designed to cover a person's ears entirely.

Management

[edit]The loss of hearing, when it is caused by neural loss, cannot presently be cured. Instead, its effects can be mitigated by the use of audioprosthetic devices, i.e. hearing assistive devices such as hearing aids and cochlear implants. In a clinical setting, this management is offered by otologists and audiologists.

Relation to health

[edit]Hearing loss is associated with Alzheimer's disease and dementia with a greater degree of hearing loss tied to a higher risk.[12] There is also an association between type 2 diabetes and hearing loss.[13]

Hearing underwater

[edit]Hearing threshold and the ability to localize sound sources are reduced underwater in humans, but not in aquatic animals, including whales, seals, and fish which have ears adapted to process water-borne sound.[14][15]

In vertebrates

[edit]

Not all sounds are normally audible to all animals. Each species has a range of normal hearing for both amplitude and frequency. Many animals use sound to communicate with each other, and hearing in these species is particularly important for survival and reproduction. In species that use sound as a primary means of communication, hearing is typically most acute for the range of pitches produced in calls and speech.

Frequency range

[edit]Frequencies capable of being heard by humans are called audio or sonic. The range is typically considered to be between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz.[16] Frequencies higher than audio are referred to as ultrasonic, while frequencies below audio are referred to as infrasonic. Some bats use ultrasound for echolocation while in flight. Dogs are able to hear ultrasound, which is the principle of 'silent' dog whistles. Snakes sense infrasound through their jaws, and baleen whales, giraffes, dolphins and elephants use it for communication. Some fish have the ability to hear more sensitively due to a well-developed, bony connection between the ear and their swim bladder. This "aid to the deaf" for fishes appears in some species such as carp and herring.[17]

Time discrimination

[edit]Human perception of audio signal time separation has been measured to less than 10 microseconds (10μs). This does not mean that frequencies above 100 kHz are audible, but that time discrimination is not directly coupled with frequency range. Georg Von Békésy in 1929 identifying sound source directions suggested humans can resolve timing differences of 10μs or less. In 1976 Jan Nordmark's research indicated inter-aural resolution better than 2μs.[18] Milind Kuncher's 2007 research resolved time misalignment to under 10μs.[19]

In birds

[edit]In invertebrates

[edit]Even though they do not have ears, invertebrates have developed other structures and systems to decode vibrations traveling through the air, or “sound”. Charles Henry Turner was the first scientist to formally show this phenomenon through rigorously controlled experiments in ants.[21] Turner ruled out the detection of ground vibration and suggested that other insects likely have auditory systems as well.

Many insects detect sound through the way air vibrations deflect hairs along their body. Some insects have even developed specialized hairs tuned to detecting particular frequencies, such as certain caterpillar species that have evolved hair with properties such that it resonates most with the sound of buzzing wasps, thus warning them of the presence of natural enemies.[22]

Some insects possess a tympanal organ. These are "eardrums", that cover air filled chambers on the legs. Similar to the hearing process with vertebrates, the eardrums react to sonar waves. Receptors that are placed on the inside translate the oscillation into electric signals and send them to the brain. Several groups of flying insects that are preyed upon by echolocating bats can perceive the ultrasound emissions this way and reflexively practice ultrasound avoidance.

See also

[edit]- Basics

- General

- Disorders

- Test and measurement

- Audiogram

- Audiometry

- Auditory brainstem response (test)

- Dichotic listening (test)

References

[edit]- ^ Plack, C. J. (2014). The Sense of Hearing. Psychology Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1848725157.

- ^ Jan Schnupp; Israel Nelken; Andrew King (2011). Auditory Neuroscience. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-11318-2. Archived from the original on 2011-01-29. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ Kung C. (2005-08-04). "A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation". Nature. 436 (7051): 647–654. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..647K. doi:10.1038/nature03896. PMID 16079835. S2CID 4374012.

- ^ Peng, AW.; Salles, FT.; Pan, B.; Ricci, AJ. (2011). "Integrating the biophysical and molecular mechanisms of auditory hair cell mechanotransduction". Nat Commun. 2: 523. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..523P. doi:10.1038/ncomms1533. PMC 3418221. PMID 22045002.

- ^ Gelfand, Stanley A. (2009). Essentials of audiology (3rd ed.). New York: Thieme. ISBN 978-1-60406-044-7. OCLC 276814877.

- ^ Daniel Schacter; Daniel Gilbert; Daniel Wegner (2011). "Sensation and Perception". In Charles Linsmeiser (ed.). Psychology. Worth Publishers. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ William Yost (2003). "Audition". In Alice F. Healy; Robert W. Proctor (eds.). Handbook of Psychology: Experimental psychology. John Wiley and Sons. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-471-39262-0.

- ^ Shojaeemend, Hassan; Ayatollahi, Haleh (2018). "Automated Audiometry: A Review of the Implementation and Evaluation Methods". Healthcare Informatics Research. 24 (4): 263–275. doi:10.4258/hir.2018.24.4.263. ISSN 2093-3681. PMC 6230538. PMID 30443414.

- ^ Keidser, Gitte; Convery, Elizabeth (2016-04-12). "Self-Fitting Hearing Aids". Trends in Hearing. 20: 233121651664328. doi:10.1177/2331216516643284. ISSN 2331-2165. PMC 4871211. PMID 27072929.

- ^ "Definition of hearing loss - hearing loss classification". hear-it.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- ^ Martini A, Mazzoli M, Kimberling W (December 1997). "An introduction to the genetics of normal and defective hearing". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 830 (1): 361–74. Bibcode:1997NYASA.830..361M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51908.x. PMID 9616696. S2CID 7209008.

- ^ Thomson, Rhett S.; Auduong, Priscilla; Miller, Alexander T.; Gurgel, Richard K. (2017-03-16). "Hearing loss as a risk factor for dementia: A systematic review". Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2 (2): 69–79. doi:10.1002/lio2.65. ISSN 2378-8038. PMC 5527366. PMID 28894825.

- ^ Akinpelu, Olubunmi V.; Mujica-Mota, Mario; Daniel, Sam J. (2014). "Is type 2 diabetes mellitus associated with alterations in hearing? A systematic review and meta-analysis". The Laryngoscope. 124 (3): 767–776. doi:10.1002/lary.24354. ISSN 1531-4995. PMID 23945844. S2CID 25569962.

- ^ "Discovery of Sound in the Sea". University of Rhode Island. 2019.

- ^ Au, W.L (2000). Hearing by Whales and Dolphins. Springer. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-387-94906-2.

- ^ D'Ambrose, Christoper; Choudhary, Rizwan (2003). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Frequency range of human hearing". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ^ Williams, C. B. (1941). "Sense of Hearing in Fishes". Nature. 147 (3731): 543. Bibcode:1941Natur.147..543W. doi:10.1038/147543b0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4095706.

- ^ Robjohns, Hugh (August 2016). "MQA Time-domain Accuracy & Digital Audio Quality". soundonsound.com. Sound On Sound. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023.

- ^ Kuncher, Milind (August 2007). "Audibility of temporal smearing and time misalignment of acoustic signals" (PDF). boson.physics.sc.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ Mills, Robert (March 1994). "Applied comparative anatomy of the avian middle ear". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 87 (3): 155–6. doi:10.1177/014107689408700314. PMC 1294398. PMID 8158595.

- ^ Turner CH. 1923. The homing of the Hymenoptera. Trans. Acad. Sci. St. Louis 24: 27–45

- ^ Tautz, Jürgen, and Michael Rostás. "Honeybee buzz attenuates plant damage by caterpillars." Current Biology 18, no. 24 (2008): R1125-R1126.

Further reading

[edit]- Lopez-Poveda, Enrique A.; Palmer, A. R. (Alan R.); Meddis, Ray. (2010). The neurophysiological bases of auditory perception. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-5685-9. OCLC 471801201.

External links

[edit]- Global Audiology- International Society of Audiology

- World Health Organization, Deafness and Hearing Loss

Media related to Hearing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hearing at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of hearing at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of hearing at Wiktionary Quotations related to Hearing at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Hearing at Wikiquote- Open University - OpenLearn - Article about hearing Archived 2018-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Preventing Occupational Noise-Induced Hearing Loss, NIOSH