Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Midbrain

View on Wikipedia| Midbrain | |

|---|---|

Figure shows the midbrain (A) and surrounding regions; sagittal view of one cerebellar hemisphere. B: Pons. C: Medulla. D: Spinal cord. E: Fourth ventricle. F: Arbor vitae. G: Nodule. H: Tonsil. I: Posterior lobe. J: Anterior lobe. K: Inferior colliculus. L: Superior colliculus. | |

Inferior view in which the midbrain is encircled blue. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | UK: /ˌmɛsɛnˈsɛfəlɒn, -kɛf-/, US: /ˌmɛzənˈsɛfələn/;[1] |

| Part of | Brainstem |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | mesencephalon |

| MeSH | D008636 |

| NeuroNames | 462 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1667 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.005 |

| TA2 | 5874 |

| FMA | 61993 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The midbrain or mesencephalon is the uppermost portion of the brainstem connecting the diencephalon and cerebrum with the pons.[2] It consists of the cerebral peduncles, tegmentum, and tectum.

It is functionally associated with vision, hearing, motor control, sleep and wakefulness, arousal (alertness), and temperature regulation.[3]

The name mesencephalon comes from the Greek mesos, "middle", and enkephalos, "brain".[4]

Structure

[edit]

A:Thalamus B:Midbrain C:Pons

D:Medulla oblongata

7 and 8 are the four colliculi.

The midbrain is the shortest segment of the brainstem, measuring less than 2cm in length. It is situated mostly in the posterior cranial fossa, with its superior part extending above the tentorial notch.[2]

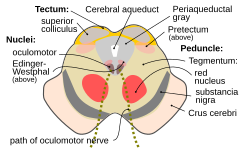

The principal regions of the midbrain are the tectum, the cerebral aqueduct, tegmentum, and the cerebral peduncles. Rostrally the midbrain adjoins the diencephalon (thalamus, hypothalamus, etc.), while caudally it adjoins the hindbrain (pons, medulla and cerebellum).[5] In the rostral direction, the midbrain noticeably splays laterally.

Sectioning of the midbrain is usually performed axially, at one of two levels – that of the superior colliculi, or that of the inferior colliculi. One common technique for remembering the structures of the midbrain involves visualizing these cross-sections (especially at the level of the superior colliculi) as the upside-down face of a bear, with the cerebral peduncles forming the ears, the cerebral aqueduct the mouth, and the tectum the chin; prominent features of the tegmentum form the eyes and certain sculptural shadows of the face.

Tectum

[edit]

The tectum (Latin for roof) is the part of the midbrain dorsal to the cerebral aqueduct.[2]The position of the tectum is contrasted with the tegmentum, which refers to the region in front of the ventricular system, or floor of the midbrain.

It is involved in certain reflexes in response to visual or auditory stimuli. The reticulospinal tract, which exerts some control over alertness, takes input from the tectum,[6] and travels both rostrally and caudally from it.

The corpora quadrigemina are four mounds, called colliculi, in two pairs – a superior and an inferior pair, on the surface of the tectum. The superior colliculi process some visual information, aid the decussation of several fibres of the optic nerve (some fibres remain ipsilateral), and are involved with saccadic eye movements. The tectospinal tract connects the superior colliculi to the cervical nerves of the neck, and co-ordinates head and eye movements. Each superior colliculus also sends information to the corresponding lateral geniculate nucleus, with which it is directly connected. The homologous structure to the superior colliculus in non mammalian vertebrates including fish and amphibians, is called the optic tectum; in those animals, the optic tectum integrates sensory information from the eyes and certain auditory reflexes.[7][page needed][8]

The inferior colliculi – located just above the trochlear nerve – process certain auditory information. Each inferior colliculus sends information to the corresponding medial geniculate nucleus, with which it is directly connected.

Cerebral aqueduct

[edit]

The cerebral aqueduct is the part of the ventricular system which links the third ventricle (rostrally) with the fourth ventricle (caudally); as such it is responsible for continuing the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid. The cerebral aqueduct is a narrow channel located between the tectum and the tegmentum, and is surrounded by the periaqueductal grey,[9] which has a role in analgesia, quiescence, and bonding. The dorsal raphe nucleus (which releases serotonin in response to certain neural activity) is located at the ventral side of the periaqueductal grey, at the level of the inferior colliculus.

The nuclei of two pairs of cranial nerves are similarly located at the ventral side of the periaqueductal grey – the pair of oculomotor nuclei (which control the eyelid, and most eye movements) is located at the level of the superior colliculus,[10] while the pair of trochlear nuclei (which helps focus vision on more proximal objects) is located caudally to that, at the level of the inferior colliculus, immediately lateral to the dorsal raphe nucleus.[9] The oculomotor nerve emerges from the nucleus by traversing the ventral width of the tegmentum, while the trochlear nerve emerges via the tectum, just below the inferior colliculus itself; the trochlear is the only cranial nerve to exit the brainstem dorsally. The Edinger-Westphal nucleus (which controls the shape of the lens and size of the pupil) is located between the oculomotor nucleus and the cerebral aqueduct.[9]

Tegmentum

[edit]

The midbrain tegmentum is the portion of the midbrain ventral to the cerebral aqueduct, and is much larger in size than the tectum. It communicates with the cerebellum by the superior cerebellar peduncles, which enter at the caudal end, medially, on the ventral side; the cerebellar peduncles are distinctive at the level of the inferior colliculus, where they decussate, but they dissipate more rostrally.[9] Between these peduncles, on the ventral side, is the median raphe nucleus, which is involved in memory consolidation.

The main bulk of the tegmentum contains a complex synaptic network of neurons, primarily involved in homeostasis and reflex actions. It includes portions of the reticular formation. A number of distinct nerve tracts between other parts of the brain pass through it. The medial lemniscus – a narrow ribbon of fibres – passes through in a relatively constant axial position; at the level of the inferior colliculus it is near the lateral edge, on the ventral side, and retains a similar position rostrally (due to widening of the tegmentum towards the rostral end, the position can appears more medial). The spinothalamic tract – another ribbon-like region of fibres – are located at the lateral edge of the tegmentum; at the level of the inferior colliculus it is immediately dorsal to the medial lemiscus, but due to the rostral widening of the tegmentum, is lateral of the medial lemiscus at the level of the superior colliculus.

A prominent pair of round, reddish, regions – the red nuclei (which have a role in motor co-ordination) – are located in the rostral portion of the midbrain, somewhat medially, at the level of the superior colliculus.[9] The rubrospinal tract emerges from the red nucleus and descends caudally, primarily heading to the cervical portion of the spine, to implement the red nuclei's decisions. The area between the red nuclei, on the ventral side – known as the ventral tegmental area – is the largest dopamine-producing area in the brain, and is heavily involved in the neural reward system. The ventral tegmental area is in contact with parts of the forebrain – the mammillary bodies (from the Diencephalon) and hypothalamus (of the diencephalon).

Cerebral peduncles

[edit]

The cerebral peduncles each form a lobe ventrally of the tegmentum, on either side of the midline. Beyond the midbrain, between the lobes, is the interpeduncular fossa, which is a cistern filled with cerebrospinal fluid [citation needed].

The majority of each lobe constitutes the cerebral crus. The cerebral crus are the main tracts descending from the thalamus to caudal parts of the central nervous system; the central and medial ventral portions contain the corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts, while the remainder of each crus primarily contains tracts connecting the cortex to the pons. Older texts refer to the crus cerebri as the cerebral peduncle; however, the latter term actually covers all fibres communicating with the cerebrum (usually via the diencephalon), and therefore would include much of the tegmentum as well. The remainder of the crus pedunculi – small regions around the main cortical tracts – contain tracts from the internal capsule.

The portion of the lobes in connection with the tegmentum, except the most lateral portion, is dominated by a blackened band – the substantia nigra (literally black substance)[9] – which is the only part of the basal ganglia system outside the forebrain. It is ventrally wider at the rostral end. By means of the basal ganglia, the substantia nigra is involved in motor-planning, learning, addiction, and other functions. There are two regions within the substantia nigra – one where neurons are densely packed (the pars compacta) and one where they are not (the pars reticulata), which serve a different role from one another within the basal ganglia system. The substantia nigra has extremely high production of melanin (hence the colour), dopamine, and noradrenalin; the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in this region contributes to the progression of Parkinson's disease.[11]

Blood supply

[edit]The midbrain is supplied by the following arteries:

- The tectum is supplied by the superior cerebellar artery.

- The central part of the tegmentum is supplied by the paramedian branches of the basilar artery.

- The lateral part of the midbrain is supplied by the posterior cerebral artery.

Venous blood from the midbrain is mostly drained into the basal vein as it passes around the peduncle. Some venous blood from the colliculi drains to the great cerebral vein.[12]

Development

[edit]

During embryonic development, the midbrain (also known as the mesencephalon) arises from the second vesicle of the neural tube, while the interior of this portion of the tube becomes the cerebral aqueduct. Unlike the other two vesicles – the forebrain and hindbrain – the midbrain does not develop further subdivision for the remainder of neural development. It does not split into other brain areas. While the forebrain, for example, divides into the telencephalon and the diencephalon.[13]

Throughout embryonic development, the cells within the midbrain continually multiply; this happens to a much greater extent ventrally than it does dorsally. The outward expansion compresses the still-forming cerebral aqueduct, which can result in partial or total obstruction, leading to congenital hydrocephalus.[14] The tectum is derived in embryonic development from the alar plate of the neural tube.

Function

[edit]The midbrain is the uppermost part of the brainstem. Its substantia nigra is closely associated with motor system pathways of the basal ganglia. The human midbrain is archipallian in origin, meaning that its general architecture is shared with the most ancient of vertebrates. Dopamine produced in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area plays a role in movement, movement planning, excitation, motivation and habituation of species from humans to the most elementary animals such as insects. Laboratory mice from lines that have been selectively bred for high voluntary wheel running have enlarged midbrains.[15] The midbrain helps to relay information for vision and hearing.

Related terms

[edit]The term "tectal plate" or "quadrigeminal plate" is used to describe the junction of the gray and white matter in the embryo. (ancil-453 at NeuroNames)

See also

[edit]- List of regions in the human brain

- Pretectal area (Pretectum)

References

[edit]- ^ "mesencephalon". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c Sinnatamby, Chummy S. (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 476. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Breedlove, Watson, & Rosenzweig. Biological Psychology, 6th Edition, 2010, pp. 45-46

- ^ Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary,≈ Fourth Edition, Mosby-Year Book 1994, p. 981

- ^ "Slide 5". Archived from the original on 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ Kandel, Eric (2000). Principles of Neural Science. McGraw-Hill. pp. 669. ISBN 0-8385-7701-6.

- ^ Collins Dictionary of Biology, 3rd ed. © W. G. Hale, V. A. Saunders, J. P. Margham 2005

- ^ Ferrier, David (1886). "Functions of the optic lobes or corpora quadrigemina". The functions of the brain (Second ed.). G P Putnam's Sons. pp. 149–173. doi:10.1037/12789-005.

- ^ a b c d e f Martin. Neuroanatomy Text and Atlas, Second edition. 1996, pp. 522-525.

- ^ Haines, Duane E. (2012). Neuroanatomy : an atlas of structures, sections, and systems (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health. pp. 42. ISBN 978-1-60547-653-7.

- ^ Damier, P.; Hirsch, E. C.; Agid, Y.; Graybiel, A. M. (1999-08-01). "The substantia nigra of the human brainII. Patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in Parkinson's disease". Brain. 122 (8): 1437–1448. doi:10.1093/brain/122.8.1437. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 10430830.

- ^ Sinnatamby, Chummy S. (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 478. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Martin. Neuroanatomy Text and Atlas, Second Edition, 1996, pp. 35-36.

- ^ "Hydrocephalus Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. February 2008. Archived from the original on November 17, 2004. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Kolb, E. M.; Rezende, E. L.; Holness, L.; Radtke, A.; Lee, S. K.; Obenaus, A.; Garland (2013). "Mice selectively bred for high voluntary wheel running have larger midbrains: support for the mosaic model of brain evolution". Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (3): 515–523. doi:10.1242/jeb.076000. PMID 23325861.