Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

B movies (Hollywood Golden Age)

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| B movies |

|---|

|

The B movie, whose roots trace to the silent film era, was a significant contributor to Hollywood's Golden Age of the 1930s and 1940s. As the Hollywood studios made the transition to sound film in the late 1920s, many independent exhibitors began adopting a new programming format: the double feature. The popularity of the twin bill required the production of relatively short, inexpensive movies to occupy the bottom half of the program. The double feature was the predominant presentation model at American theaters throughout the Golden Age, and B movies constituted the majority of Hollywood production during the period.

Roots of the B movie: 1910s–1920s

[edit]

It is not clear that the term B movie (or B film or B picture) was in general use before the 1930s; in terms of studio production, however, a similar concept was already well established. In 1916, Universal became the first Hollywood studio to establish different feature brands based on production cost: the small Jewel line of "prestige" productions, midrange Bluebird releases, and the low-budget Red Feather line of five-reelers—a measure of film length indicating a running time between fifty minutes and an hour. The following year, the Butterfly line, a grade between Red Feather and Bluebird, was introduced. During those two years, about half of Universal's output was in the Red Feather and Butterfly categories.[2] According to historian Thomas Schatz, "These low-grade westerns, melodramas, and action pictures...underwent a disciplined production and marketing process," in contrast to the Jewels, which were not as strictly governed by studio policies.[3] While the down-market branding was soon eliminated, Universal continued to focus on low and modestly budgeted productions. In 1919, wealthy Paramount Pictures created its own distinct low-budget brand, Realart Studio (Realart Pictures Corp.), "a small studio with four companies and four stars" Bebe Daniels, Marguerite Clark, Wanda Hawley, and Mary Miles Minter.[4][5][6][7][8] Paramount Pictures' Realart Studio' films were made attractive to exhibitors with lower rental fees than movies from the studio's primary production line.[9] Indicating the breadth of the budgetary range at a single studio, in 1921, when the average cost of a Hollywood feature was around $60,000,[10] Universal spent approximately $34,000 on The Way Back, a five-reeler, and over $1 million on Foolish Wives, a top-of-the-line Super Jewel.[11] The production of inexpensive films like The Way Back allowed the studios to derive maximum value from facilities and contracted staff in between a studio's more important productions, while also breaking in new personnel.[12]

By 1927–28, at the end of the silent era, the production cost of an average feature from Hollywood's major film studios had soared, ranging from $190,000 at Fox to $275,000 at MGM.[10] These averages, again, reflected "specials" and "superspecials" that might cost as much as $1 million and films made quickly for around $50,000.[13] Some studios, like large Paramount and growing Warner Bros., depended on block booking and blind bidding practices, under which "independent ('unaffiliated') theater owners were forced to take large numbers of the studio's pictures sight unseen. Those studios could then parcel out second-rate product along with A-class features and star vehicles, which made both production and distribution operations more economical."[14] Studios in the minor leagues of the industry, such as Columbia Pictures and Film Booking Offices of America (FBO), focused on low-budget productions; most of their movies, with relatively short running times, targeted theaters that had to economize on rental and operating costs—particularly those in small towns and so-called neighborhood venues, or "nabes," in big cities. Even smaller outfits—the sort typical of Hollywood's so-called Poverty Row—made films whose production costs might run as low as $3,000, seeking a profit through whatever bookings they could pick up in the gaps left by the larger concerns.[15]

With the widespread arrival of sound film in American theaters in 1929, many independent exhibitors began dropping the then-dominant presentation model, which involved live acts and a broad variety of shorts before a single featured film.[16] A new programming scheme developed that would soon become standard practice: a newsreel, a short and/or a serial, and a cartoon, followed by a double feature. The second feature, which actually screened before the main event, cost the exhibitor less per minute than the equivalent running time in shorts. The majors' comprehensive booking policy, which would become known as the run-zone-clearance system, inadvertently pushed independent theaters toward adopting the double-feature format. As described by historian Thomas Schatz, the system "sent a picture, after playing in the lucrative first-run arena, through the 16,000 'subsequent-run' movie houses; 'clearance' refers to the amount of time between runs, and 'zone' refers to the specific areas in which a film played.

Typically, a top feature would play in its second run in smaller downtown theaters [many major-affiliated] and then move steadily outward from the urban centers to the suburbs, then to smaller cities and towns, and finally to rural communities, playing in ever smaller (and less profitable) venues and taking upwards of six months to complete its run."[17] The "clearance" policy prevented independent exhibitors' timely access to top-quality films as a matter of course; the second feature allowed them to promote quantity instead.[18] The bottom-billed movie also gave the program "balance"—the practice of pairing different sorts of features suggested to potential customers that they could count on something of interest no matter what specifically was on the bill. As the president of one Poverty Row company would later put it, "Not everybody likes to eat cake. Some people like bread, and even a certain number of people like stale bread rather than fresh bread."[19] The low-budget picture of the 1920s naturally transformed into the second feature, the B movie, of the 1930s and 1940s—the most reliable bread of Hollywood's Golden Age.

Rise of the double feature: 1930s

[edit]The major companies upon which the Hollywood studio system was built had been resistant to the B-movie trend, but they soon adapted. All ultimately established "B units" to provide films for the expanding second-feature market. Block booking increasingly became standard practice: in order to get access to a studio's attractive A pictures, many theaters were obliged to rent the company's entire output for a season. With the B films rented at a flat fee (rather than the box office percentage basis of A films), rates could be set that essentially guaranteed the profitability of every B movie. Blind bidding, which grew in parallel with block booking, meant that the majors didn't have to worry much about the quality of their B's—even when booking in less than seasonal blocks, exhibitors had to buy most pictures sight unseen. The five largest studios—MGM, Paramount, Fox Film Corporation (Twentieth Century Fox as of 1935), Warner Bros., and RKO Radio Pictures (descendant of Film Booking Offices of America)—had the additional advantage of being part of companies that also owned sizable theater chains, further securing the bottom line.

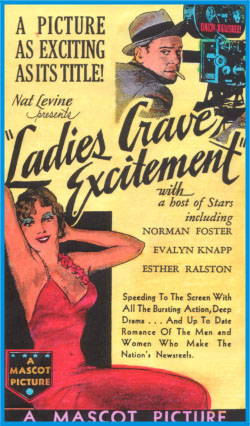

Poverty Row studios, from modest outfits like Mascot Pictures, Tiffany Studios, and Sono Art-World Wide Pictures on down to shoestring operations, made exclusively B movies, serials, and other shorts. They also distributed totally independent productions and imported films. These studios were in no position to directly block book; instead, they mostly sold regional distribution exclusivity to "states rights" distributors, who would in turn peddle blocks of films to exhibitors, typically six or more movies featuring the same star (a relative status on Poverty Row).[20] Two studios in the middle—the "major-minors" Universal and Columbia, moving up in rank—had production lines roughly similar to the top Poverty Row concerns, if somewhat better endowed in general, and with a few up-market productions each year as well. They had few or no theaters, but they did have major-league-level distribution exchanges.[21]

In the model that would be standard during the Golden Age, the industry's top product, its A films, would premiere at a select number of deluxe first-run metropolitan cinemas, located in U.S. cities with populations in the range of 100,000 and above. There were fewer than 500 of these downtown movie palaces; in 1934, 77 percent of them were under the control of one or the other of the leading studios, the "Big Five."[22] As a whole, the first-run circuit comprised the palaces and another 900 or so houses covering North America's 400 largest municipalities. Double features, though sometimes employed, were the rule at few if any of these prestigious venues. As described by historian Edward Jay Epstein, "During the[ir] first runs, films got their reviews, garnered publicity, and generated the word of mouth that served as the principal form of advertising."[23] After a film's opening run, it was off to the nabes and the hinterland, the subsequent-run market where the double feature prevailed.[24] At the larger local venues controlled by the majors, movies might turn over on a weekly basis. At the thousands of small theaters that belonged to independent chains or were individually owned, programs often changed two or three time a week, sometimes even faster. To keep up with the constant demand for new B product, the low end of Poverty Row turned out a stream of micro-budget movies rarely much more than sixty minutes long; these were known as "quickies" for their tight production schedules—a week's shooting was about average, just four days was not unheard of.[25] As historian Brian Taves describes, "Many of the poorest theaters, such as the 'grind houses' in the larger cities, screened a continuous program emphasizing action with no specific schedule, sometimes offering six quickies for a nickel in an all-night show that changed daily."[26] Many small theaters never saw a big-studio A film, getting their movies from the states rights concerns that handled almost exclusively Poverty Row product. Millions of Americans went to their local theaters as a matter of course: for an A picture, along with the trailers, or screen previews, that had presaged its arrival, "[t]he new film's title on the marquee and the listings for it in the local newspaper constituted all the advertising most movies got."[27] Aside from at the theater itself, B films might not be advertised at all.

The introduction of sound had driven costs higher. In 1930, the beginning of the Golden Age's first full decade, the average U.S. feature film cost $375,000 to produce.[28] A broad range of Hollywood motion pictures occupied the B-movie category: The leading studios made not only clear-cut A and B films, but also movies classifiable as "programmers" (also "in-betweeners" or "intermediates"). These were films that "straddle[d] the A-B boundary," in Taves's description. During the era of the double feature, "[d]epending on the prestige of the theater and the other material on the double bill, a programmer could show up at the top or bottom of the marquee."[29] On Poverty Row, many B's were made on budgets that would have barely covered petty cash on a major's A film, with costs at the bottom of the industry running as low as $5,000.[25] By the middle of the 1930s, the double feature was the dominant exhibition model across the country, and the majors responded. In 1935, B-movie production at Warner Bros. was raised from 12 to 50 percent of the studio's total output. The unit was headed by Bryan Foy, known as the "Keeper of the B's."[30] At Fox, which also shifted half of its production line into B territory, Sol M. Wurtzel was similarly in charge of more than twenty movies a year during the late 1930s. Loew's, the parent company of MGM, announced in 1935 that it would run double features at all of its subsequent-run theaters. A low-cost production unit was established at the studio under Lucien Hubbard, "although the term B movie was strictly taboo at Metro."[31] Columbia, which primarily served the B-movie market, expanded annual production from thirty pictures to more than forty.[32]

A number of the top Poverty Row firms were consolidating: Sono Art-World Wide Pictures joined with Rayart Pictures to create Monogram Pictures early in the decade. In 1935, Monogram Pictures, Mascot Pictures, Liberty Pictures, Majestic Pictures, Chesterfield Pictures, and Invincible Pictures merged to form Republic Pictures. After little more than a year, the heads of Monogram pulled out and revived their company. Into the 1950s, Republic and Monogram released films that tended to be roughly on par with the low end of the majors' output. Less sturdy Poverty Row concerns—with a penchant for grand sobriquets like Conquest, Empire, Imperial, Supreme Pictures and Peerless—continued to churn out dirt-cheap quickies.[33] As the majors increased their B-level production and Republic and Monogram began to dominate Poverty Row, many of these smaller outfits folded by 1937.[34]

Hollywood studio feature film, average length, 1938

[edit]Joel Finler has analyzed the average length of feature film releases from the various Hollywood studios in 1938, which indicates the degree, to which, each emphasized the production of B films:[35]

|

The Big Five majors MGM—87.9 minutes Paramount—76.4 minutes 20th Century-Fox—75.3 minutes Warner Bros.—75.0 minutes RKO—74.1 minutes |

The Little Three majors United Artists[36]—87.6 minutes Columbia—66.4 minutes Universal—66.4 minutes |

Poverty Row (top three of many) Grand National[37]—63.6 minutes Republic—63.1 minutes Monogram—60.0 minutes |

Brian Taves estimates that half of the films produced by the eight majors in the 1930s were B movies. Calculating in the three hundred or so films made annually by the many Poverty Row firms, approximately 75 percent of Hollywood movies from the decade, more than four thousand pictures, are classifiable as B's.[38] Outside of the highly standardized realm of the series picture, studio executives saw developmental opportunities in their B lines of production. In 1937, RKO production chief Sam Briskin described his company's B films as "a testing ground for new names, and experiments in story and treatment."[39]

Cowboys, dogs and detectives

[edit]

The western was by far the predominant B genre in both the 1930s and, to a somewhat lesser degree, the 1940s; for most of the Golden Age, westerns of every stripe accounted for 25 to 30 percent of all Hollywood feature production.[40] Film historian Jon Tuska has argued that "the 'B' product of the Thirties—the Universal films with [Tom] Mix, [Ken] Maynard, and [Buck] Jones, the Columbia features with Buck Jones and Tim McCoy, the RKO George O'Brien series, the Republic westerns with John Wayne and the Three Mesquiteers...achieved a uniquely American perfection of the well-made story."[41] At the far end of the industry, Poverty Row's Ajax put out films starring Harry Carey, then in his fifties. The Weiss outfit had the Range Rider series, the American Rough Rider series, and the Morton of the Mounted "northwest action thrillers" that gave top billing to Dynamite, the Wonder Horse and Captain, the King of Dogs.[42] One notable low-budget western of the era, produced totally outside of the studio system, made money off a curious concept: a western with an all-midget cast, The Terror of Tiny Town (1938) was such a success in its independent bookings that Columbia picked it up for distribution.[43]

Series, or serials, of various genres were particularly popular during the first decade of sound film. At just one major studio, Fox, B series produced by Sol Wurtzel included "Charlie Chan, Mr. Moto, Sherlock Holmes, Michael Shayne, the Cisco Kid, George O'Brien westerns [before his move to RKO], the Gambini sports films, the Roving Reporters, the Camera Daredevils, the Big Town Girls, the hotel for women, the Jones Family, the Jane Withers children's films, Jeeves, [and] the Ritz Brothers."[44] These feature-length series films are not to be confused with the short, cliffhanger-structured serials that sometimes appeared on the same program. As with serials, however, many series were specifically intended to interest young people—some of the theaters that twin-billed part-time might run a "balanced" or entirely youth-oriented double feature as a matinee and then a single film for a more mature audience at night. In the words of a contemporary Gallup industry report, afternoon moviegoers, "composed largely of housewives and children, want quantity for their money while the evening crowds want 'something good and not too much of it.'"[45]

Series films are often unquestioningly consigned to the B-movie category, but even here there is ambiguity, as scholar James Naremore describes:

The most profitable B pictures functioned much like the comic strips in the daily newspapers, showing the continuing adventures of Roy Rogers [Republic], Boston Blackie [Columbia], the Bowery Boys [Warner Bros./Universal], Blondie and Dagwood [Columbia], Charlie Chan [Fox/Monogram], and so on. Even a major studio like MGM [the industry leader from 1931 through 1941] was equipped with a so-called B unit that specialized in these serial productions. At MGM, however, the Andy Hardy, Dr. Kildaire [sic], and Thin Man films were made with major stars and with what some organizations would have considered A budgets.[46]

For some series, of course, even a major studio's B budget was far out of reach: Poverty Row's Consolidated Pictures, backed by Weiss, featured Tarzan, the Police Dog in a series with the proud name of Melodramatic Dog Features.[47]

A few down-market independent productions were more ambitious: White Zombie (1932), directed by Victor Halperin and starring Béla Lugosi, is now regarded as the archetypal zombie movie, though it was poorly received at the time.[48] It was picked up by United Artists for distribution after it lost deals with Columbia and the small Educational Pictures.[49] On occasion, a low-end movie would get separated from the pack. Reviewing the 77-minute Universal crime melodrama Rio (1939), The New York Times declared that director "John Brahm's impact on the Class B picture is producing one of the strangest sound effects in recent cinema history. It is that of an unmistakable B buzzing like an A."[50]

Bs from major to minor: 1940s

[edit]

By 1940, the average production cost of an American feature was $400,000, a negligible increase over ten years.[28] A number of small Hollywood companies had folded around the turn of the decade, including the ambitious Grand National, but a new firm, Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), emerged as third in the Poverty Row hierarchy behind Republic and Monogram. The double feature, never universal, was still the prevailing exhibition model: in 1941, 50 percent of theaters were double-billing exclusively, with additional numbers screening under the policy part-time.[51] In the early 1940s, legal pressure forced the studios to replace seasonal block booking with packages generally limited to five pictures (MGM carried on with blocks of twelve for a while). Restrictions were also placed on the majors' ability to enforce blind bidding.[52] These were crucial factors in the progressive shift by most of the Big Five over to A-film production, making the smaller studios even more important as B-movie suppliers. In 1944, for instance, MGM, Paramount, Fox, and Warners released a total of ninety-five features: fourteen had B-level budgets of $200,000 or less; eleven were budgeted between $200,000 and $500,000, a range encompassing programmers as well as straight B movies on the lower end; and seventy were A budgeted at $0.5 million or more.[53] In late 1946, executives at the newly merged Universal-International announced that no U-I feature would run less than seventy minutes; supposedly, all B pictures were to be discontinued, even if they were in the midst of production.[54] The studio did release three more sub-70-minute films: two Cinecolor westerns, The Michigan Kid and The Vigilantes Return, in 1947; the self-explanatory Arctic Manhunt in 1949.[55] Fox also phased out B production in 1946, releasing low-budget unit chief Bryan Foy, "The Keeper of the Bees" who had come over from Warners five years before when Warners stopped making their B pictures. For its B-picture needs, the studio turned to independent producers like the now-freelance Sol Wurtzel.[56]

Genre pictures made at very low cost remained the backbone of Poverty Row, with even Republic's and Monogram's budgets rarely climbing over $200,000. According to Naremore, between 1945 and 1950, "the average B western from Republic Pictures was made for about $50,000."[57] Among the established studios, Monogram was exploring fresh territory with what were being called "exploitation pictures." Variety defined these as "films with some timely or currently controversial subject which can be exploited, capitalized on in publicity or advertising."[58] Many smaller Poverty Row firms were folding because there simply was not enough money to go around: the eight majors, with their proprietary distribution exchanges, were now "taking in around 95 percent of all domestic (U.S. and Canada) rental receipts."[17] The wartime shortage of film stock was another contributing factor.[59]

Referencing the work of historian Lea Jacobs, Naremore describes how the line between A and B movies was "ambiguous and never dependent on money alone."[60] Films shot on B-level budgets were occasionally marketed as A pictures or emerged as sleeper hits: One of 1943's biggest films was Hitler's Children, an 82-minute-long RKO thriller made for a fraction over $200,000. It earned more than $3 million in rentals, industry language for a distributor's share of gross box office receipts.[61] The violent Dillinger (1945), made for a reported $35,000, earned Monogram more than $1 million for the first time.[62] A pictures, particularly in the realm of film noir, sometimes echoed visual styles generally associated with cheaper films. Between November 1941 and November 1943, Dore Schary ran what was effectively a "B-plus" unit at MGM.[63] Programmers, with their flexible exhibition role, were ambiguous by definition, leading in certain cases to historical confusion. As late as 1948, the double feature remained a popular exhibition mode—it was the standard screening policy at 25 percent of theaters and used part-time at an additional 36 percent.[64] The leading Poverty Row firms began to broaden their scope: In 1947, Monogram established a subsidiary, Allied Artists, as a development and distribution channel for relatively expensive films, mostly from independent producers. Around the same time, Republic launched a similar effort under the "Premiere" rubric.[65] In 1947 as well, PRC was subsumed by Eagle-Lion, a British company seeking entry to the American market. Warners' (and Fox's) former Keeper of the B's, Brian Foy, was installed as production chief.[66]

Sinners and saints

[edit]

In the 1940s, RKO—the weakest of the Big Five throughout its history—stood out among the industry's largest companies for its focus on B pictures. From a latter-day perspective, the most famous of the major studios' Golden Age B units is Val Lewton's horror unit at RKO. Lewton produced such moody, mysterious films as Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and The Body Snatcher (1945), directed by Jacques Tourneur, Robert Wise, and others who would become renowned only later in their careers or entirely in retrospect. The movie now widely described as the first classic film noir—Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a 64-minute B—was produced at RKO, which would release many melodramatic thrillers in a similarly stylish vein during the decade. The other major studios also turned out a considerable number of movies now identified as noir during the 1940s. Though many of the best-known film noirs were well-financed productions—the majority of Warner Bros. noirs, for instance, were produced at the studio's A level—most 1940s pictures in the mode were either of the ambiguous programmer type or destined straight for the bottom of the bill. In the decades since, these cheap entertainments, generally dismissed at the time, have become some of the most treasured products of Hollywood's Golden Age among aficionados.[68]

In one sample year, 1947, RKO under production chief Dore Schary shot fifteen A-level features at an average cost of $1 million and twenty Bs averaging $215,000.[69] In addition to several noir programmers and full-flight A pictures, the studio put out two straight B noirs: Desperate, directed by Anthony Mann, and The Devil Thumbs a Ride, directed by Felix E. Feist. Ten straight B noirs that year came from Poverty Row's big three: Republic (Blackmail and The Pretender), Monogram (Fall Guy, The Guilty, High Tide, and Violence), and PRC/Eagle-Lion (Bury Me Dead, Lighthouse, Whispering City, and Railroaded, another work of Mann). One came from tiny Screen Guild (Shoot to Kill). Three majors beside RKO also contributed: Columbia (Blind Spot and Framed), Paramount (Fear in the Night), and 20th Century-Fox (Backlash and The Brasher Doubloon). Adding programmers to that list of eighteen would bring it to around thirty. Still, most of the majors' low-budget production during the decade was of the sort now largely ignored. RKO's representative output included the Mexican Spitfire and Lum and Abner comedy series, thrillers featuring the Saint and the Falcon, westerns starring Tim Holt, and Tarzan movies with Johnny Weissmuller. Jean Hersholt played Dr. Christian in six independently produced films released by RKO between 1939 and 1941. The Courageous Dr. Christian (1940) was a standard entry in the franchise: "In the course of an hour or so of screen time, the saintly physician managed to cure an epidemic of spinal meningitis, demonstrate benevolence towards the disenfranchised, set an example for wayward youth, and calm the passions of an amorous old maid."[70]

Down in Poverty Row, low budgets led to less palliative fare. Republic aspired to major-league respectability while making many cheap and modestly budgeted westerns, but there was not much from the bigger studios that compared with Monogram "exploitation pictures" like juvenile delinquency exposé Where Are Your Children? (1943) and the prison film Women in Bondage (1943).[71] In 1947, PRC's The Devil on Wheels brought together teenagers, hot rods, and death. The little studio had its own house auteur: with his own crew and relatively free rein, director Edgar G. Ulmer was known as "the Capra of PRC."[72] Described by critic and historian David Thomson as "one of the most fascinating talents in the worldwide labyrinth of sub-B pictures," Ulmer made films of every generic stripe.[73] His Girls in Chains was released in May 1943, six months before Women in Bondage; by the end of the year, Ulmer had also made the teen-themed musical Jive Junction as well as Isle of Forgotten Sins, a South Seas adventure set around a brothel.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hirschhorn (1999), pp. 9–10, 17.

- ^ Hirschhorn (1983), pp. 13, 20–27.

- ^ Schatz (1998), p. 22.

- ^ File:Victoria Daily Times (1921-07-08) (IA victoriadailytimes19210708).pdf p.11

- ^ commons:Category:Realart Pictures Inc.

- ^ "Production Company: Realart". Catalog. AFI. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Realart's relationship to Paramount". NitrateVille.com. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Kay, Karyn and Gerald Peary (July 16, 2011). "Interview with Dorothy Arzner". Agnès Films.

- ^ Eames (1985), p. 13.

- ^ a b Finler (2003), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Koszarski (1994), pp. 112, 113, 115; Schatz (1998), 22–25.

- ^ See, e.g., Balio (1995), p. 29; Koszarski (1994), p. 72.

- ^ Balio (1995), p. 29.

- ^ Schatz (1998), p. 39. See also p. 74; Koszarski (1994), pp. 71–72.

- ^ See, e.g., Taves (1995), p. 320.

- ^ See Koszarski (1994), pp. 34–56.

- ^ a b Schatz (1999), p. 16.

- ^ Balio (1995), p. 29. See also Schatz (1999), p. 324, for specific applications of "clearance."

- ^ Steve Broidy, president of Monogram Pictures/Allied Artists, quoted in Schatz (1999), p. 75.

- ^ Taves (1995), pp. 326–27.

- ^ See, e.g., Balio (1995), pp. 103–4.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 16; Biesen (2005), p. 228, n. 6.

- ^ Epstein (2005), p. 6. See also Schatz (1999), pp. 16–17.

- ^ See Waterman (2005), pp. 48–52, for a detailed examination of how the release system worked in practice.

- ^ a b Taves (1995), p. 325.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 326.

- ^ Epstein (2005), p. 4.

- ^ a b Finler (2003), p. 42.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 317. Taves (like this article) adopts the usage of "programmer" argued for by author Don Miller in his 1973 study B Movies (New York: Ballantine). As Taves notes, "the term programmer was used in a variety of different ways by reviewers" of the 1930s (p. 431, n. 8). Some present-day critics employ the Miller–Taves usage; others refer to any B movie from the Golden Age as a "programmer" or "program picture."

- ^ Balio (1995), p. 102.

- ^ Schatz (1998), pp. 170–71.

- ^ Balio (1995), p. 103.

- ^ See Taves (1995), pp. 321–29.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 321.

- ^ Adapted from Finler (2003), p. 26.

- ^ United Artists directly produced no features, focusing instead on the distribution of prestigious films made by independent outfits.

- ^ In operation from 1936 to 1940, Grand National Pictures was something like the United Artists of Poverty Row. Most of the films it released were the work of independent producers; in its peak year, 1937, Grand National did produce approximately twenty pictures of its own. See also Taves (1995), p. 323.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 313.

- ^ Quoted in Lasky (1989), p. 142.

- ^ Nachbar (1974), p. 2.

- ^ Tuska (1974), p. 37.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 327–28.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 316.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 318.

- ^ Quoted in Schatz (1999), p. 75.

- ^ Naremore (1998), p. 141. For more on the finances and industrial position of the Andy Hardy movies, see Schatz (1998), pp. 256–61.

- ^ Taves (1995), p. 328.

- ^ Prawer (1989), p. 68.

- ^ Rhodes (2001), pp. 111–13.

- ^ Nugent (1939), p. 31.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 73.

- ^ Schatz (1999), pp. 19–21, 45, 72, 160–63. See also Taves (1995), pp. 314–15.

- ^ Analysis based on Schatz (1999), p. 173, table 6.3.

- ^ Hirschhorn (1983), p. 156.

- ^ Hirschhorn (1983), pp. 172, 173, 182.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 335.

- ^ Naremore (1998), p. 140.

- ^ Quoted in Schatz (1999), p. 175.

- ^ Buhle and Wagner (2003), p. 154.

- ^ Naremore (1998), p. 141.

- ^ Jewell (1982), 181; Lasky (1989), 184–85.

- ^ Cost: Per screenwriter Philip Yordan, commentary track on Warner Home Video DVD of film. Earnings: Schatz (1999), p. 175.

- ^ Schatz (1998), pp. 367–70.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 78.

- ^ Schatz (1999), pp. 340–41.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 295; Naremore (1998), p. 142; PRC (Producers Releasing Corporation) essay by Mike Haberfelner, August 2005; part of the (re)Search my Trash website. Retrieved 12/30/06.

- ^ Robert Smith, "Mann in the Dark," quoted in Ottoson (1981), p. 145.

- ^ See, e.g., Dave Kehr, "Critic's Choice: New DVDs," New York Times, August 22, 2006; Dave Kehr, "Critic's Choice: New DVDs," New York Times, June 7, 2005; Robert Sklar, "Film Noir Lite: When Actions Have No Consequences," New York Times, "Week in Review," June 2, 2002.

- ^ Schatz (1998), pp. 442–43.

- ^ Jewell (1982), p. 147.

- ^ Schatz (1999), p. 175.

- ^ Naremore (1998), p. 144.

- ^ Thomson (1994), p. 764.

Sources

[edit]- Balio, Tino (1995 [1993]). Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20334-8

- Biesen, Sheri Chinen (2005). Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8217-6

- Buhle, Paul, and David Wagner (2003). Hide in Plain Sight: The Hollywood Blacklistees in Film and Television, 1950-2002. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6144-1

- Eames, John Douglas (1985). The Paramount Story. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-55348-1

- Epstein, Edward Jay (2005). The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6353-1

- Finler, Joel W. (2003). The Hollywood Story, 3d ed. London and New York: Wallflower. ISBN 1-903364-66-3

- Hirschhorn, Clive (1983). The Universal Story. London: Crown. ISBN 0-517-55001-6

- Hirschhorn, Clive (1999). The Columbia Story. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-59836-5

- Jewell, Richard B., with Vernon Harbin (1982). The RKO Story. New York: Arlington House/Crown. ISBN 0-517-54656-6

- Koszarski, Richard (1994 [1990]). An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08535-3

- Lasky, Betty (1989). RKO: The Biggest Little Major of Them All. Santa Monica, Calif.: Roundtable. ISBN 0-915677-41-5

- McCarthy, Todd, and Charles Flynn, eds. (1975). Kings of the Bs: Working Within the Hollywood System—An Anthology of Film History and Criticism. New York: E.P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-47378-5

- Nachbar, Jack, ed. (1974). Focus on the Western. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-950626-8

- Naremore, James (1998). More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21294-0

- Nugent, Frank S. (1939). "John Brahm's Direction Distinguishes 'Rio' at the Globe—'Pack Up Your Troubles' at the Palace," New York Times, October 27.

- Ottoson, Robert (1981). A Reference Guide to the American Film Noir: 1940–1958. Metuchen, N.J., and London: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1363-7

- Prawer, Siegbert Salomon (1989). Caligari's Children: The Film as Tale of Terror. New York: Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80347-X

- Rhodes, Gary Don (2001). White Zombie: Anatomy of a Horror Film. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0988-6

- Schatz, Thomas (1998 [1989]). The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19596-2

- Schatz, Thomas (1999 [1997]). Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22130-3

- Taves, Brian (1995 [1993]). "The B Film: Hollywood's Other Half," in Balio, Grand Design, pp. 313–350.

- Thomson, David (1994). A Biographical Dictionary of Film, 3d ed. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-679-75564-0

- Tuska, Jon (1974). "The American Western Cinema: 1903–Present," in Nachbar, Focus on the Western, pp. 25–43.

- Waterman, David (2005). Hollywood's Road to Riches. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01945-8