Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

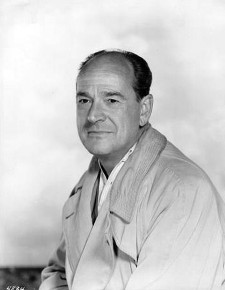

Anthony Mann

View on Wikipedia

Anthony Mann (born Emil Anton Bundsmann; June 30, 1906 – April 29, 1967) was an American film director and stage actor.[1] He came to prominence as a skilled director of film noir and Westerns, and for his historical epics.[1]

Key Information

Mann started as a theatre actor appearing in numerous stage productions. In 1937, he moved to Hollywood where he worked as a talent scout and casting director. He then became an assistant director, most notably working for Preston Sturges. His directorial debut was Dr. Broadway (1942). He directed several feature films for numerous production companies, including RKO Pictures, Eagle-Lion Films, Universal Pictures, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). His first major success was T-Men (1947), garnering notable recognition for producing several films in the film noir genre through modest budgets and short shooting schedules. As a director, he often collaborated with cinematographer John Alton.

During the 1950s, Mann shifted to directing Western films starring several major stars of the era, including James Stewart. He directed Stewart in eight films, including Winchester '73 (1950), The Naked Spur (1953), and The Man from Laramie (1955). While successful in the United States, these films became appreciated and studied among French film critics, several of whom would become influential with the French New Wave. In 1955, Jacques Rivette hailed Mann as "one of the four great directors of postwar Hollywood". The other three were Nicholas Ray, Richard Brooks, and Robert Aldrich.[2]

By the 1960s, Mann turned to large-scale filmmaking, directing the medieval epic El Cid (1961), starring Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren, and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Both films were produced by Samuel Bronston. Mann then directed the war film The Heroes of Telemark (1965)[3] and the spy thriller A Dandy in Aspic (1968). In 1967, Mann died from a heart attack in Berlin before he had finished the latter film; its star Laurence Harvey completed the film, albeit uncredited.

Early life

[edit]Mann was born Emil Anton Bundsmann in San Diego, California. His father, Emile Theodore Bundsmann, an academic, was born in the village of Rosice, Chrudim, Bohemia to a Sudeten-German Catholic family.[4] His mother, Bertha (née Waxelbaum/Weichselbaum),[5] a drama teacher from Macon, Georgia,[6] was an American of Bavarian Jewish descent.[7] At the time of his birth, Mann's parents were members of the Theosophical Society community of Lomaland in San Diego County.[6]

When Mann was three, his parents moved to Austria to seek treatment for his father's ill health, leaving Mann behind in Lomaland. Mann's mother did not return for him until he was fourteen, and only then at the urging of a cousin who had paid him a visit and was worried about his treatment and situation at Lomaland.[8] In 1917, Mann's family relocated to New York where he developed a penchant for acting. This was reinforced with Mann's participation in the Young Men's Hebrew Association.[6] He continued to act in school productions, studying at East Orange Grammar and Newark's Central High School. At the latter school, he portrayed the title role in Alcestis; one of his friends and classmates was future Hollywood studio executive Dore Schary.[9] After his father's death in 1923, Mann dropped out during his senior year to help with the family's finances.[6][7][a]

Career

[edit]1925–1937: Theater career

[edit]Back in New York, Mann took a job as a night watchman for Westinghouse Electric, which enabled him to look for stage work during the day. Within a few months, Mann was working full-time at the Triangle Theater in Greenwich Village.[6] Using the name "Anton Bundsmann", he appeared as an actor in The Dybbuk (1925) with an English translation by Henry Alsberg, The Little Clay Cart (1926), and The Squall (1926) by Jean Bart.[11][12] Towards the end of the decade, Mann appeared in the Broadway productions of The Blue Peter[13] and Uncle Vanya (1929).[12]

In 1930, Mann joined the Theatre Guild, as a production manager and eventually as a director. Nevertheless, he continued to act, appearing in The Streets of New York, or Poverty is No Crime (1931),[14] and The Bride the Sun Shines On (1933) portraying the "Duke of Calcavalle".[12] In 1933, Mann directed a stage adaptation of Christopher Morley's Thunder on the Left, which was performed at the Maxine Elliott's Theatre.[15] In a theatre review for The New York Times, Brooks Atkinson dismissed the play, writing "its medley of realism and fantasy grows less intelligible scene by scene, and some of the acting is disenchantingly profane."[16] He later directed Cherokee Night (1936), So Proudly We Hail (1936),[17] and The Big Blow (1938).[11][18] He worked for various stock companies, and in 1934, he established his own, which later became Long Island's Red Barn Playhouse.[19]

1937–1941: Move to Hollywood and television career

[edit]In 1937, Mann began working for Selznick International Pictures as a talent scout and casting director. He also directed screen tests for a number of films, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938), Intermezzo (1939), Gone with the Wind (1939), and Rebecca (1940). One of the unknown actresses he tested was Jennifer Jones.[20][21] After a few months at Selznick, Mann moved to Paramount Pictures to serve as an assistant director for several film directors, most particularly for Preston Sturges on Sullivan's Travels (1941).[22] Mann recalled, "[Preston] let me go through the entire production, watching him direct – and I directed a little. I'd stage a scene and he'd tell me how lousy it was. Then I watched the editing and I was able gradually to build up knowledge. Preston insisted I make a film as soon as possible."[23] He served three years in the position.[24]

Meanwhile, Mann did notable, but mostly lost, work as a director for NBC's experimental television station W2XBS from 1939 to 1940. This included condensations of the hit Western play The Missouri Legend and the melodrama The Streets of New York. A five-minute silent clip of the latter show survives in the Museum of Television and Radio, including noted actors Norman Lloyd and George Coulouris.[25]

1942–1946: Move to directing

[edit]Through the efforts of his friend MacDonald Carey, Mann made his directorial debut with Dr. Broadway (1942) at Paramount, which starred Carey.[24] Decades later, Mann remembered he was told to complete shooting the film in eighteen days.[23] Upon its release, Herman Schoenfeld of Variety was dismissive of the film writing, "The dialog could have just as well have been written in baby talk, and Anton Mann's direction just wasn't. The photography is spotty and the production looks inexpensive. Acting is weak, only Edward Ciannelli as the killer who gets killed, turning in an adequate job."[26] Harrison's Reports was more complimentary, stating the film was a "fairly good program entertainment" with "colorful characters, human interest, fast action, and situations that hold one in suspense."[27]

His follow-up film was Moonlight in Havana (1943) at Universal Pictures. The film featured Allan Jones and Jane Frazee.[28] In August 1944, it was reported Mann might return to Broadway to direct Mirror for Children.[29] After nine months without directing a feature film, Mann went to Republic Pictures where he directed Nobody's Darling (1944) and My Best Gal (1944).[30]

He next directed Strangers in the Night (1944). The film tells of Hilda Blake (Helene Thimig) who creates an imaginary "daughter" for Sgt. Johnny Meadows (William Terry) who is injured in the South Pacific. After being discharged and returning to the U.S., Meadows searches for the imaginary woman. He is informed of the truth by Dr. Leslie Ross (Virginia Grey), who is later murdered by Blake; in turn, Blake plans to murder Meadows.[31] The film was notable for its noirish mise-en-scène and psychological depth that appeared in Mann's latter films.[32] Mann then directed The Great Flamarion (1945), starring Erich von Stroheim and Mary Beth Hughes.[33] During principal photography, Mann clashed with von Stroheim, describing him at length as "difficult. He was a personality, not really an actor ... He drove me mad. He was a genius. I'm not a genius: I'm a worker."[34]

Mann moved to RKO to direct Two O'Clock Courage (1945), itself a remake of the 1936 film Two in the Dark,[35] with Tom Conway and Ann Rutherford in the leading roles.[36] That same year, he also directed Sing Your Way Home. Mann returned to Republic Pictures for Strange Impersonation (1946). He directed The Bamboo Blonde (1946) at RKO.

1947–1949: Film noir and career breakthrough

[edit]By 1946, Mann had signed with Eagle-Lion Films, a fledgling studio founded by Arthur B. Krim and Robert Benjamin. There, he directed Railroaded! (1947). According to Mann, the film was shot in ten days.[37] A film review in Variety noted the film was "an old-type, blood-and-thunder gangster meller that's better than its no-name cast would indicate," and particular praised Mann for directing "with real acumen in developing maximum of suspense."[38]

That same year, T-Men (1947) was released. According to Elmer Lincoln Irey, the film originated from a rejected offer to dramatize the U.S. Treasury's investigation of Al Capone on tax evasion charges. Instead, Irey brought forward three cases related to the investigation.[39] Initially budgeted at $400,000, T-Men was shot within three weeks from July 31 to August 23, with four days of reshoots in September.[40] For the film, Mann specifically requested cinematographer John Alton, who was loaned out from Republic for the job,[41][42] marking T-Men as their first collaboration.[37] During its release, the film earned $2.5 million worldwide.[43]

He went back to RKO for Desperate (1947), which he also co-wrote with Dorothy Atlas.[33] A review in Variety positively wrote it was "a ripsnorting gangster meller, with enough gunplay, bumping off of characters and grim brutality to smack of pre-code days"; Mann's direction was noted as "being done skillfully".[44]

Mann returned to Eagle-Lion to direct Raw Deal (1948), reteaming with screenwriter John C. Higgins, screenwriter Leopold Atlas and actor Dennis O'Keefe. The film centers on Joe (O'Keefe), who has been wrongly imprisoned and fingered by his old friends. He escapes from prison and goes on the run with two women, a nice social worker, Ann (Marsha Hunt), whom he takes as a hostage, and a femme fatale, Pat (Claire Trevor), who helped release him. Both women are doomed to be in love with him.[45] The film review magazine Harrison's Reports wrote: "Fast-paced and packed with action, this gangster-type melodrama should go over pretty well with adult audiences, in spite of the fact that the plot is not always logical"; it also noted "Anthony Mann's taut direction has squeezed every bit of excitement and suspense out of the material at hand."[46] Variety noted: "Though a medium budgeter, [Raw Deal] is dressed tidily with a good production and some marquee weight furnished by" the cast.[47] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times gave the film a negative review, writing it is "a movie—and a pretty low-grade one, at that—in which sensations of fright and excitement are more diligently pursued than common sense."[48]

Mann's success with Desperate and T-Men made him Eagle-Lion's most valuable director.[49] In February 1948, Mann was hired to direct a dramatization of the storming of the Bastille, with Richard Basehart to portray an aide to General Lafayette.[50] With Walter Wanger preoccupied with Joan of Arc (1948), he handed off supervisory duties to production designer William Cameron Menzies.[49] Principal photography lasted 29 days, from August to September 1948,[49] and cost $850,000.[51] Reteaming with Alton, he and Mann developed a low-cost noir style, using low lighting levels and omnipresent shadows on minimal decor, high-angled camera shots, and rear projection for wide crowd shots.[49] The resulting film was titled Reign of Terror (1949). After filming had begun, Mann was brought in to direct several scenes for He Walked by Night (1948), which also starred Basehart. Mann again collaborated with Higgins and Alton on the film. However, Alfred L. Werker was given the official director's credit.[52]

While researching on T-Men (1947), Higgins and Mann had come across the topic of Border Patrol agents along the Mexico–United States border.[53] Border Incident (1949) was initially developed at Eagle-Lion, but in December 1948, MGM's Dore Schary purchased the script for $50,000 and hired Mann to direct the film. Schary had also signed Mann onto a multi-picture contract with MGM.[54][55]

Beforehand, in July 1947, Mann and Francis Rosenwald had written a script for Follow Me Quietly (1949). It was first purchased by Jack Wrather Productions for Allied Artists, with Don Castle in the lead role.[56] According to Eddie Muller, of Turner Classic Movies, Mann was slated to direct the film, but was enticed by Edward Small to instead direct T-Men and Raw Deal.[57] Months later, in December, RKO had purchased the script from Wrather and assigned Martin Rackin write a new script.[58] Due to Mann's absence, Richard Fleischer was hired to direct Follow Me Quietly, and there has been speculation suggesting Mann did uncredited filming.[59] However, Muller has disagreed.[57]

Mann and Rosenwald wrote another script titled Stakeout, which told of a police detective attempting to expose a corrupt political machine. In October 1949, independent film producer Louis Mandel purchased the script, with Larry Parks cast in the lead role. Joseph H. Lewis was set to direct the film until he left due to a contractual dispute. By March 1950, Parks's wife Betty Garrett was cast in the femme fatale role, but the project never went into production.[60]

1950–1958: Western films and collaborations with James Stewart

[edit]The 1950s marked a notable turn in Mann's career, in which he directed a total of ten Western films throughout the decade (three of which were released in 1950).[61] After Border Incident (1949), Mann was approached by Nicholas Nayfack, who asked him: "How would you like to direct a Western? I've a scenario here that seems interesting." He was handed the script for Devil's Doorway (1950), deeming it "the best script I had ever read."[62] The film starred Robert Taylor, portraying a Shoshone native who faces prejudice after returning home in Medicine Bow, Wyoming following his decorated service in the American Civil War. Principal photography began on August 15, 1949, and lasted until mid-October. MGM initially withheld the film because of its topical subject, but released the film after Delmer Daves' Broken Arrow (1950), which starred James Stewart, had become successful.[63] When it was released, the film was neither a critical or commercial success.[64]

He followed this with a Western at Universal, starring James Stewart, Winchester '73 (1950). The film was originally set to be directed by Fritz Lang, but he felt Stewart was unsuitable for the lead role and dropped out. When Stewart had seen a rough cut of Devil's Doorway (1950), he suggested Mann as a replacement. Mann readily accepted, but threw out the script calling Borden Chase for a rewrite.[65] Principal photography began on February 14, 1950, in Tucson, Arizona for a thirty-day shooting schedule.[66] The film was a commercial success, earning $2.25 million in distributor rentals becoming Universal Pictures' second-most successful film of 1950.[67][68]

At the invitation of Hal Wallis, Mann directed the Western The Furies (1950) at Paramount starring Barbara Stanwyck and Walter Huston.[67] Also released in summer 1950, the film grossed $1.55 million in distributor rentals in the United States and Canada.[68] Mann reflected, "It had marvellous characters, interesting notices, but it failed because nobody in it cared about anything—they were all rudderless, rootless, and haters."[69] In the fall of 1950, Mann was sent to Cinecittà to do second-unit work on Quo Vadis (1951).[70] There, Mann worked 24 nights, filming the burning of Rome sequence with assistant cinematographer William V. Skall.[71]

Side Street (1950) was the final film noir that Mann directed. The film starred Farley Granger and Cathy O'Donnell, reteaming after They Live by Night (1948). He next directed a period thriller with Dick Powell, The Tall Target (1952).[65]

After the success of Winchester '73 (1950), Universal Pictures wanted another collaboration between Mann and Stewart. After a recommendation from one friend, Stewart proposed adapting the novel Bend of the River by Bill Gulick to Universal. The studio agreed and purchased the film rights.[72] The actor and director made a contemporary adventure film, Thunder Bay (1953) at Universal. Feeling dissatisfied with the final film, Mann stated, "We tried but it was all too fabricated and the story was weak. We were never able to lick it ...It didn't get terribly good notices but of course it made a profit."[73]

In 1952, MGM approached Mann to direct The Naked Spur (1953). The story told of bounty hunter Howard Kemp who wants to collect a $5,000 reward on an outlaw's head so he can buy back land lost to him during the American Civil War. With unwanted help from a gold prospector and an Army deserter, Kemp captures the outlaw and the girlfriend who accompanies him.[74] With the film's release in 1953, Mann fulfilled his contract with MGM.[75][76]

Mann and Stewart had their biggest success with The Glenn Miller Story (1954). During its release, the film earned $7 million in distributor rentals in the United States and Canada.[77] That same year, he filmed The Far Country with James Stewart and Walter Brennan. The film would be Mann's last collaboration with Borden Chase.[75]

Mann and Stewart paired for one more non-Western film, Strategic Air Command (1955). Stewart had served with the U.S. Air Force and pushed for a cinematic portrayal. With the cooperation of the Air Force, Mann agreed to direct the film, wanting to film the Convair B-36 and Boeing B-47 in action as the human characters, in his words, "were papier-mâché".[78] During its release, the film earned $6.5 million at the box office.[79]

Mann's last collaboration with Stewart was The Man from Laramie (1955) at Columbia Pictures. The film was an adaptation from a serial by Thomas T. Flynn, first published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1954. The film was shot on location in Coronado, New Mexico, and in Sante Fe.[80] The film was the favorite of Stewart's of the films they made together.[72] After the film's release, Harry Cohn asked Mann to direct another Western film for Columbia. Mann agreed and decided to direct The Last Frontier (1955).[81] Mann offered Stewart the lead role to which he declined and instead cast Victor Mature.[80]

In 1956, Mann was handed the script for Night Passage (1957) by Aaron Rosenberg, intending to reunite him with Stewart for a potential ninth collaboration.[82][83] Before filming was set to begin on September 4, Mann withdrew from the project. Contemporary accounts reported that Mann withdrew because he had not yet finished editing Men in War (1957).[84] However, latter accounts state Mann had developed creative differences with Chase over the script, which Mann considered to be weak. In 1967, Mann had also accused Stewart of only doing the film so he could play his accordion.[82] Mann asked to be replaced, and James Neilson was hired to direct the film.[85] Stewart and Mann never collaborated on another project again.[86]

Mann directed a musical starring Mario Lanza titled Serenade (1956).[87] During filming, he worked with actress Sara Montiel, who became his second wife.[88] In August 1957, Mann announced he had acquired the film rights to Lion Feuchtwanger's novel This is the Hour, which told a fictionalized account of painter Francisco Goya. Montiel was set to portray Maria Teresa de Cayetana, Duchess of Alba.[89] By February 1958, Mann had abandoned the project as a rival film titled The Naked Maja (1958) was in production. He then purchased the film rights to John McPartland's then-recently published novel Ripe Fruit, with Montiel set to star.[90] However, the project failed to materialize.

Mann directed a Western starring Henry Fonda and Anthony Perkins titled The Tin Star (1957).[91] Mann then teamed with Philip Yordan on two films starring Robert Ryan and Aldo Ray; the first being Men in War (1957) was about the Korean War. The film was the first of three Mann had directed for United Artists.[92] His second project was a 1958 film adaptation of Erskine Caldwell's then-controversial novel God's Little Acre. Mann and producer Sidney Harmon had intended to film in Augusta, Georgia, but the novel's controversial subject matter heightened resistance from city leaders and local farmers. As a result, the production was denied permission to film in the state.[93][94] In October 1957, they eventually selected Stockton, California.[95] On both films, Yordan was given the official screenwriter credit, but Ben Maddow stated he had written both screenplays.[96]

Mann later directed Gary Cooper in a Western, Man of the West (1958) for United Artists. Filming began on February 10, 1958,[97] and ended later that same year. When it was released, Howard Thompson of The New York Times wrote the film was "good, lean, tough little Western" that was "[w]ell-acted and beautifully photographed in color and Cinema-Scope".[98] Elsewhere, Jean-Luc Godard, then a critic for Cahiers du Cinéma, gave the film a raving review when it was released in France.[99]

1959–1964: Widescreen films

[edit]Mann was hired by Universal Pictures to direct Spartacus (1960), much to the disagreement of Kirk Douglas who felt Mann "seemed scared of the scope of the picture".[100] Filming started on January 27, 1959, in Death Valley, California for the mine sequence. As filming continued, Douglas felt Mann had lost control of the film, writing in particular: "He let Peter Ustinov direct his own scenes by taking every suggestion Peter made. The suggestions were good—for Peter, but not necessarily for the film."[101] With the studio's approval, Douglas was permitted to fire Mann. According to Douglas's account, Mann graciously exited the production on February 13, to which Douglas promised he "owe[d]" a film to him.[102] In 1967, Mann stated: "Kirk Douglas was the producer of Spartacus: he wanted to insist on the message angle. I thought the message would go over more easily by showing physically all the horrors of slavery. A film must be visual, too much dialogue kills it ... From then, we disagreed: I left."[103] On February 17, 1959, Stanley Kubrick was hired to direct.[104]

Shortly after, Mann went to MGM to direct Glenn Ford in a remake of Cimarron (1960). During production, Mann had filmed on location for twelve days, but the shoot had experienced troublesome storms. In response, studio executives at MGM decided to relocate the production indoors. Mann disagreed, remarking the production had become "an economic disaster and a fiasco and the whole project was destroyed."[105] Mann left the production, and was replaced by Charles Walters.[106]

In July 1960, Mann was hired to direct El Cid (1961) for Samuel Bronston.[107] The film starred Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren. In November 1960, before filming was to begin, Loren was displeased with her dialogue in the script, and requested for blacklisted screenwriter Ben Barzman to rewrite it. On an airplane trip to Rome, Mann retrieved Barzman and handed him the latest shooting script, to which Barzman agreed to rewrite from scratch.[108] Filming began on November 14, 1960, and lasted until April 1961. Released in December 1961, El Cid was released to critical acclaim, with praise towards Mann's direction, the cast and the cinematography.[109] At the box office, the film earned $12 million in distributor rentals from the United States and Canada.[110]

Mann next directed The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). The project's genesis began when Mann, who had recently finished filming El Cid (1961), had spotted an Oxford concise edition of Edward Gibbon's six-volume series The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire near the front window at the Hatchards bookshop. Mann then read the book, and after a flight trip to Madrid, he pitched a film adaptation of the book to Bronston, to which the producer agreed.[111] The film was intended to reunite Heston and Loren, but Heston departed the project to star in 55 Days at Peking (1963), another Bronston production. His role was subsequently assumed by Stephen Boyd.[112] Filming began on January 14, 1963, and wrapped in July 1963. Released in March 1964, the film earned $1.9 million in box office rentals in the United States and Canada,[113] against an estimated production budget of $16 million.[114] That same year, in July, Mann served as the head of the jury at the 14th Berlin International Film Festival.[115]

1965–1967: Later films

[edit]In March 1963, Mann and producer S. Benjamin Fisz had reportedly begun development on The Unknown Battle, a historic re-telling of Norwegian resistance soldier Knut Haukelid's sabotage mission to prevent Nazi Germany from developing an atomic bomb during World War II. Barzman had been hired to write the script, with Allied Artists as a distributor.[116] By February 1964, Boyd and Elke Sommer had been hired to portray the leading roles.[117] However, in July, Kirk Douglas was hired to portray the lead role.[118] In his memoir, Douglas accepted the role after receiving an unexpected phone call from Mann, fulfilling his earlier promise that he "owed" him a film.[119] The film was then re-titled The Heroes of Telemark (1965).

In October 1966, Mann was announced to direct and produce the spy thriller A Dandy in Aspic (1968) for Columbia Pictures.[120] By December, filming was set to begin in February 1967 where it would film on location in Austria, Germany, and London.[121] At the time of his death, Mann was developing three projects: a Western film titled The King, which was loosely adapted from King Lear, with sons replacing the daughters;[103][122] The Donner Pass, a film about pioneers trekking to the Donner Pass; and The Canyon, a film about a young Native American becoming a Brave.[103]

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1936, Mann married Mildred Kenyon, who worked as a clerk at a Macy's department store in New York City.[123] The marriage produced two children, Anthony and Nina. The couple divorced in 1956.[124] A year later, Mann married actress Sara Montiel, who had starred in Serenade (1956).[24] In 1963, the marriage was annulled in Madrid.[125] His third marriage was to Anna Kuzko, a ballerina formerly with Sadler's Wells, who had one son named Nicholas.[19][126]

On April 29, 1967, Mann died from a heart attack in his hotel room in Berlin. He had spent the two weeks prior to his death filming A Dandy in Aspic. The film was completed by the film's star Laurence Harvey.[10][19] For his contribution to the motion picture industry, he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6229 Hollywood Boulevard.[127]

Filmmaking style

[edit]Portrayal of antiheroes

[edit]The Mann western hero has learned wariness the hard way, because he usually has something to hide. He is a man with a past: some psychic shadow or criminal activity that has left him gnarled and calcified. Not so long ago he was a raider, a rustler, maybe a killer. If a movie were made of some previous chapter in his life, he'd be the villain, and he might be gunned down before he had the chance at redemption that Mann's films offer.

Mann's filmography has been observed for his depiction of antiheroes.[b] In 2006, Richard Corliss observed that Mann's antiheroes typically have a troubled past, leaving them jaded or cynical at the start of the film, and are presented with a path to redemption.[45] Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Pierre Sauvage noted the troubled past in Mann's several films have included "the death of a loved one (a father in Winchester '73 and The Furies, a brother in The Man from Laramie, a wife in The Tin Star), and the hero is out to punish the responsible party or, as in the case of The Tin Star, resents society as a whole for what happened."[131]

By the 1950s, Mann had shifted to directing Western films, with Winchester '73 (1950) as his first collaboration with James Stewart. Aaron Rosenberg, who had produced the film, observed: "He [Mann] also brought out something in James Stewart that hadn't been really been seen before. It was an almost manic rage that would suddenly explode ... And then Stewart's character would just go into a violent rage which was a fresh approach, not just for Stewart but also for the Western. Here was a hero with flaws."[132] In The Naked Spur (1953), Howard Kemp (Stewart) is a bounty hunter intent on bringing a fugitive back to Kansas. When faced with the choice to kill the fugitive, Kemp reins in his murderous impulse. Corliss observed: "It happens over and over in these movies: the hero's recognition that his old self is his own worst enemy."[45]

Mann and Stewart had a falling out during pre-production of Night Passage (1957), in which Gary Cooper assumed the lead role in Man of the West (1958).[133] Mann biographer Jeanine Basinger writes Cooper's character is a "man with a guilty secret. He was once an evil outlaw, a member of the notorious Dock Tobin gang. He was responsible for robberies, raids, and the murders of innocent victims."[134] In the film, Link Jones (Cooper) is confronted by his outlaw uncle Dock Tobin (Lee J. Cobb), a figure of his past. In the narrative, Link realizes he must kill all the gang members not only to save himself but also to restore the world which he has made for himself.[135]

Use of landscapes

[edit]Mann's portrayal of the American landscape in his Westerns have been observed by film academics.[c] In a 1965 interview, Mann expressed his preference for location filming, stating: "Well, the use of the location is to enhance the characters who are involved in it, because somebody who is really minor in feelings and minor as an actor can become tremendous once he's set against a tremendously pictorial background. The great value of using locations is that it enhances everything: it enhances the story; it enhances the very action and the acting. I'll never show a piece of scenery, a gorge, a chasm, without an actor in it."[138]

Coursodon and Sauvage noted Mann incorporates landscapes as part of the narrative, writing "His camera is never too close to isolate, never too far to dwarf. He is not interested in beauty per se, neither does he care much for symbolism. He had an unfailing flair for selecting exteriors that were not only adapted to the requirements of the script but came across as the embodiment of the psychological and moral tensions in it."[136] During filming for Cimarron (1960), Mann's preference for location shooting ran into conflict with MGM producer Sol Lesser, who relocated the production indoors, which forced Mann's departure from the film.[103]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Genre | Studio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | Dr. Broadway | Mystery comedy | Paramount Pictures |

| Moonlight in Havana | Romantic comedy | Universal Pictures | |

| 1943 | Nobody's Darling | Musical | Republic Pictures |

| 1944 | My Best Gal | Comedy | |

| 1945 | Strangers in the Night | Film noir | |

| The Great Flamarion | |||

| Sing Your Way Home | Musical film | RKO Radio Pictures | |

| Two O'Clock Courage | Film noir | ||

| 1946 | Strange Impersonation | Republic Pictures | |

| The Bamboo Blonde | Romantic comedy | RKO Radio Pictures | |

| 1947 | T-Men | Film noir | Eagle-Lion Films |

| Railroaded! | |||

| Desperate | RKO Radio Pictures | ||

| 1948 | Raw Deal | Eagle-Lion Films | |

| 1949 | Reign of Terror | Historical thriller | |

| Border Incident | Film noir | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | |

| Side Street | |||

| 1950 | The Furies | Western | Paramount Pictures |

| Winchester '73 | Universal Pictures | ||

| Devil's Doorway | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | ||

| 1951 | The Tall Target | Historical thriller | |

| 1952 | Bend of the River | Western | Universal-International |

| 1953 | The Naked Spur | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | |

| Thunder Bay | Adventure | Universal-International | |

| 1954 | The Glenn Miller Story | Biographical drama | |

| The Far Country | Western | Universal Pictures | |

| 1955 | Strategic Air Command | War drama | Paramount Pictures |

| The Man from Laramie | Western | Columbia Pictures | |

| The Last Frontier | |||

| 1956 | Serenade | Musical | Warner Bros. |

| 1957 | The Tin Star | Western | Paramount Pictures |

| Men in War | War | Security Pictures/United Artists | |

| 1958 | God's Little Acre | Drama | |

| Man of the West | Western | United Artists | |

| 1960 | Cimarron | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | |

| 1961 | El Cid | Historical epic | Samuel Bronston Productions/Allied Artists |

| 1964 | The Fall of the Roman Empire | Samuel Bronston Productions/Paramount Pictures | |

| 1965 | The Heroes of Telemark | War | The Rank Organisation |

| 1968 | A Dandy in Aspic | Spy thriller | Columbia Pictures |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Alvarez writes, "In New Jersey, Emile Anton attended elementary school in East Orange and high school in Newark but dropped out to go to work." However, Mann's obituary in The New York Times reports him leaving high school at age sixteen, but the Central High School transcripts indicate a January 1925 dropout date, when Emile Anton was eighteen.[10]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[128][129][130]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references: [136][137]

Sources

[edit]- ^ a b Sadoul & Morris 1972, p. 167.

- ^ Coursodon & Sauvage 1983, p. 238.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (August 11, 2025). "Forgotten British Film Studios: The Rank Organisation, 1965 to 1967". Filmink. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ farní úřad: Chrast, sign. 3745. Zámrsk Regional Archive. 1869. p. 53.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Darby 2009, p. 5.

- ^ a b Alvarez 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Wakeman 1987, p. 723.

- ^ a b "Anthony Mann, 60, A Movie Director; Filmmaker Who Favored Westerns Dies in Berlin". The New York Times. April 30, 1967. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

Anthony Mann, the American film director, died here of a heart attack this morning. His age was 60.

- ^ a b Bassinger 2007, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Darby 2009, p. 6.

- ^ "The Blue Peter Broadway Original Cast". Broadway World. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Atkinson, J. Brooks (October 7, 1931). "The Play". The New York Times. p. 33. ProQuest 99118255.

- ^ "The Theatre". The Wall Street Journal. November 2, 1933. ProQuest 131085423.

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks (November 1, 1933). "The Play: 'Thunder on the Left,' Adapted From Christopher Morley's Novel By Jean Ferguson Black". The New York Times. p. 25. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "The THEATRE". Wall Street Journal. September 26, 1936. ProQuest 128847757.

- ^ "News of the Stage". The New York Times. May 2, 1938. ProQuest 102633334.

- ^ a b c "Film Producer Anthony Mann Dies in Berlin". Los Angeles Times. April 30, 1967. Section A, p. 4. ProQuest 155699607. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 32; Wakeman 1987, p. 723

- ^ L. L. (May 2, 1937). "Leonard Lyons prowls about gathering priceless nuggets". The Washington Post. ProQuest 150907121.

- ^ Spoto 1990, p. 171.

- ^ a b Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Bassinger 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, pp. 24–30.

- ^ Schoenfeld, Herman (May 6, 1942). "Film Reviews: Dr. Broadway". Variety. p. 6. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "'Dr. Broadway' with MacDonald Carey and Jean Philips". Harrison's Reports. May 9, 1942. p. 75. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Solozow, Sam (August 15, 1944). "Rogers Play Ready for a New Tryout". The New York Times. p. 20. ProQuest 106803331.

- ^ Wakeman 1987, p. 724.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Smith, Robert E. (1977). "Mann in the Dark: The Film Noirs of Anthony Mann". Bright Lights (5): 8–15. ISSN 0147-4049.

- ^ a b Darby 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (August 2, 1944). "McCrea Will Resume Career in Farm Story". Los Angeles Times. Part I, p. 10. ProQuest 165522052 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 35.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Railroaded". Variety. October 8, 1947. p. 8. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Heymann, Curt L. (October 26, 1947). "Now It's the T-Men". The New York Times. p. 4X. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, p. 113.

- ^ Alton 2013, p. xxix.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, p. 104.

- ^ "Eddie Small as '1-Man Industry': 16 Pix in 18 Mos. Costing 8 1/2 Million". Variety. June 16, 1948. p. 4. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Desperate". Variety. May 14, 1947. p. 15. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d Corliss, Richard (August 4, 2006). "Mann of the Hour". Time. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "'Raw Deal' with Dennis O'Keefe, Claire Trevor and Marsha Hunt". Harrison's Reports. May 22, 1948. p. 83. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Schoenfeld, Herman (May 19, 1948). "Film Reviews: Raw Deal". Variety. p. 6. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (July 9, 1948). "The Screen". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Bernstein 2000, p. 230.

- ^ Parsons, Louella O. (February 4, 1948). "Broadway Star Richard Basehart Signed for Lead in 'The Bastille'". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 13. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Costumer at 850G Keys Ingenuity on Prod. Economies". Variety. November 3, 1948. pp. 3, 16. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 37.

- ^ Darby 2009, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Brady, Thomas F. (December 21, 1948). "Metro is Planning Low-Budget Films: 'Border Incident,' To Be Made Next Year, First of Series – Cost Set at $550,000". The New York Times. p. 33. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (July 31, 1947). "Gwenn 'Hills' Medico; Douglas Seeks Classic". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 3. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Muller, Eddie (host) (October 28, 2018). "Follow Me Quietly (1949)". Noir Alley (On-air commentary). Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (December 24, 1947). "Mitchum Deal on Fire; Young Stars Promoted". Los Angeles Times. Part I, p. 7. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 90.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, p. 169.

- ^ Coursodon & Sauvage 1983, p. 239; Wakeman 1987, p. 725

- ^ Missiaen 1967, p. 46; Wakeman 1987, p. 725; Bassinger 2007, p. 67

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 12.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 74.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1987, p. 725.

- ^ Eliot 2006, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1987, p. 726.

- ^ a b "Top Grosses of 1950". Variety. January 3, 1951. p. 58. Retrieved October 19, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Fenwick & Armytage 1965, p. 186.

- ^ Wakeman 1987, p. 726; Alvarez 2013, p. 214

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b Pickard 1992, p. 106.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 38; Wakeman 1987, p. 727; Pickard 1992, p. 113

- ^ Munn 2006, p. 214.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1987, p. 727.

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Arneel, Gene (January 5, 1955). "$12,000,000 in Domestic B.O." Variety. p. 5. Retrieved October 20, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 38.

- ^ Pickard 1992, p. 114.

- ^ a b Eliot 2006, p. 238.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, p. 49.

- ^ a b Missiaen 1967, p. 49.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (July 31, 1956). "'Moll Flanders' for Lollobrigida; Mann Again Stewart's Guide". Los Angeles Times. Part I, p. 17. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mann Changes Assignment". The New York Times. August 29, 1956. p. 25. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Pickard 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Pryor, Thomas M. (March 30, 1956). "Lanza Is Signed for Warner Film". The New York Times. p. 11. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 17.

- ^ "Goya's Life Story Planned as Film". The New York Times. August 15, 1957. p. 18. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Pryor, Thomas M. (February 25, 1958). "Couple May Make More MGM Films". The New York Times. p. 23. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Pryor, Thomas M. (July 26, 1956). "Kazan Film Role for Patricia Neal". The New York Times. p. 21. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (November 27, 1956). "Anthony Mann to Film Old Play on Frighter; Wallis Keeps Holliman". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 7. Retrieved November 12, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Civic Heave-Ho For Films Not on the Boost". Variety. August 14, 1957. pp. 1, 61. Retrieved November 12, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Pryor, Thomas M. (August 9, 1957). "Wanted to Rent: God's Little Acre". The New York Times. p. 11. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Knickerbocker, Paine (October 20, 1957). "'God's Little Acre' in the West". The New York Times. p. X5. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (1997). "Philip Yordan". Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. University of California Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-520209-08-4.

- ^ "Hollywood Production Pulse". Variety. March 5, 1958. p. 21. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (October 2, 1958). "A New Double Bill". The New York Times. p. 44. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Godard, Jean-Luc (February 1959). "Super Mann: L'Homme de l'Ouest". Cahiers du Cinéma (in French). Vol. 16, no. 92. pp. 48–50. Retrieved October 6, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Douglas 1989, p. 288.

- ^ Douglas 1989, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Douglas 1989, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d Missiaen 1967, p. 50.

- ^ "Kubrick Replaces Mann". Variety. February 18, 1959. p. 17. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Wicking & Pattison 1969, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Tatara, Paul. "Cimarron (1960)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (July 6, 1960). "Bronston Discovers El Cid's Spain". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barzman 2003, pp. 306–313.

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 23.

- ^ "All-Time Top Film Grossers". Variety. January 8, 1964. p. 37.

- ^ Mann, Anthony (March 1964). "Empire Demolition". Films and Filming. Vol. 10, no. 6. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (May 14, 1962). "Boyd Will Co-star in 'Roman Empire' Cast Opposite Lollobrigida; Hope Plans Film in Africa". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 12. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Big Rental Pictures of 1964". Variety. January 6, 1965. p. 39.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (March 20, 1964). "'Roman Empire' Has $16 Million Look: Pageantry and Performances in Bronston Film Praised". Los Angeles Times. Part V, p. 14. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Berlinale 1964: Juries". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (March 18, 1963). "Ice Age Reverses Black, White Roles: Nazis' A-Bomb Plot Bared; Palance, Montgomery Travel". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (February 9, 1964). "Pictures and People". The New York Times. p. X9. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "'Unknown Battle' to Star Douglas". Los Angeles Times. July 13, 1964. Part IV, p. 18. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Douglas 1989, p. 352.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (October 31, 1966). "Who Follows the Trickiest Spy?". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 22. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Martin, Betty (December 3, 1966). "Four Added to 'Perils' Cast". Los Angeles Times. Part I, p. 18. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (March 23, 2000). "Anthony Mann: Man of the West". The Guardian. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 7.

- ^ "Actress Obtains Annulment". Buffalo Evening News. September 27, 1963. Section III, p. 40. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Alvarez 2013, p. 244.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Anthony Mann". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

North side of the 6200 block of Hollywood Boulevard

- ^ Coursodon & Sauvage 1983, pp. 239–241.

- ^ Kitses 2004, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Brunick, Paul (June 25, 2010). "On The Nature of Mann". Bomb Magazine. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Coursodon & Sauvage 1983, p. 241.

- ^ Munn 2006, p. 199.

- ^ Munn 2006, p. 238.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 118.

- ^ Darby 2009, p. 145.

- ^ a b Coursodon & Sauvage 1983, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 5, 2002). "Mann of the West". Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Fenwick & Armytage 1965, p. 187.

Works cited

[edit]Biographies (chronological)

- Bassinger, Jeanine (2007) [1979]. Anthony Mann: New and Expanded Edition. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-819-56845-8.

- Wakeman, John (1987). "Anthony Mann". World Film Directors: Volume 1—1890–1945. H. W. Wilson. pp. 723–731. ISBN 978-0-824-20757-1.

- Darby, William (2009). Anthony Mann: The Film Career. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-786-43839-6.

Miscellaneous

- Alton, John (2013) [1995]. Painting with Light. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27584-3.

- Alvarez, Max (2013). The Crime Films of Anthony Mann. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-617-03924-9.

- Barzman, Norma (2003). The Red and the Blacklist: The Intimate Memoir of a Hollywood Expatriate. Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-560-25617-5.

- Bernstein, Matthew (2000) [1994]. Walter Wanger, Hollywood Independent. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3548-X.

- Coursodon, Jean-Pierre; Sauvage, Pierre (1983). "Anthony Mann". American Directors, Volume 1. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 237–243. ISBN 0-07-013263-1.

- Douglas, Kirk (1989). The Ragman's Son: An Autobiography. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-63718-5.

- Eliot, Mark (2006). Jimmy Stewart: A Biography. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-400-05222-6.

- Fenwick, J. H; Armytage, Jonathan-Green (Fall 1965). "Now You See It: Landscape and Anthony Mann". Sight and Sound. 34 (4): 186–189.

- Horton, Robert (March 1990). "Mann & Stewart: Two Rode Together". Film Comment. 26 (2): 40. ProQuest 210251212.

- Kitses, Jim (2004). "Anthony Mann: The Overreacher". Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. London: British Film Institute. pp. 139–172.

- Missiaen, Jean-Claude (December 1967). "A Lesson in Cinema: Interview with Anthony Mann" (PDF). Cahiers du Cinéma in English (Interview). No. 12. pp. 44–51 – via Monoskop.

- Munn, Michael (2006). Jimmy Stewart: The Truth Behind the Legend. London: Robson Books. ISBN 978-1-861-05961-1.

- Pickard, Roy (1992). Jimmy Stewart: A Life in Film. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312088280.

- Sadoul, Georges; Morris, Peter (1972). Peter Morris (ed.). Dictionary of film makers. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02151-8.

- Sarris, Andrew (1968). The American Cinema: Directors and Directions: 1929–1968. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-47227-8.

- Spoto, Donald (1990). Madcap: The Life of Preston Sturges. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-80726-5.

- Wicking, Christopher; Pattison, Barrie (July 1969). "Interviews with Anthony Mann". Screen. 10 (4–5): 32–54. doi:10.1093/screen/10.4-5.32.

- Wood, Robin (June 1998). "Man(n) of the West(ern)". CineAction. No. 46. pp. 26–33.

External links

[edit]- Anthony Mann at the Internet Broadway Database (as Anton Bundsmann)

- Anthony Mann at IMDb

- Anthony Mann Profile at Allmovie by Rovi

- Anthony Mann Profile at Turner Classic Movies

Anthony Mann

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early life

Anthony Mann was born Emil Anton Bundsmann on June 30, 1906, in the Lomaland Theosophical commune in San Diego, California, to his father, an immigrant from Austria-Hungary, and his American mother.[5] His father, Emile Theodore Bundsmann, was a chemical engineer and academic originally from Bohemia who held a Ph.D. from the University of Vienna, while his mother, Bertha Waxelbaum, came from a wealthy Jewish family involved in the textile trade.[6] The Bundsmann family, including the only child Emil, converted to Theosophy and became deeply involved in the Lomaland community, a utopian enclave founded in 1897 that emphasized arts, culture, and spiritual enlightenment under leader Katherine Tingley.[7] Around age 3, following his father's illness, Mann was left at the commune while his parents separated geographically; his mother moved to New Jersey, and he joined her there around 1920 at age 14. Raised in this environment until his early teens, Mann received an education at Lomaland's Raja Yoga Academy, where he was immersed in the performing arts from a young age.[6] The commune's dramatic society staged elaborate productions of ancient Greek tragedies, Shakespearean plays, and original pageants, providing Mann with his initial exposure to theater through family connections and school activities.[7] His mother died in 1941.[5] Around age 18, Mann anglicized his identity by adopting the stage name Anton Mann as he pursued opportunities in the performing arts, eventually moving to the New York area in the mid-1920s to seek work on the stage.[8] He later changed his professional name to Anthony Mann in 1942 upon transitioning to film directing.[6]Personal life

Mann was married three times during his adult life. His first marriage, to Mildred Kenyon in 1931, produced two children—a son, Anthony, and a daughter, Nina—and ended in divorce in 1956.[9] In 1957, he wed Spanish actress Sara Montiel, a union that was annulled in 1963.[9] Mann's third marriage was to Anna Mann in 1964; the couple had one son, Nicholas Anthony Mann.[10] In his early Hollywood years after transitioning from theater in 1937, Mann endured financial hardships while working as a casting director and extra, often scraping by on low-paying gigs amid the competitive studio system.[11] Success with mid-1950s Westerns, including collaborations that elevated his status, eventually led to greater affluence, allowing for a more comfortable lifestyle.[8] He developed a personal interest in photography, using it to explore visual composition outside his professional directing, and enjoyed travel, which influenced his appreciation for diverse landscapes reflected in his later epic films.[12] Mann's political engagement was limited, with brief involvement in anti-fascist efforts during the World War II period through Hollywood circles, though he avoided major public activism thereafter.[5]Death

In 1967, Anthony Mann was diagnosed with heart issues while working on the spy thriller A Dandy in Aspic in Europe. He collapsed on the set in Berlin and died on April 29, 1967, at the age of 60, from chronic arteriosclerosis leading to a heart attack.[13][14] Mann's body was returned to London for a private funeral service, after which he was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium; his ashes were scattered there in Section 3-S.[4] The production of A Dandy in Aspic was left unfinished at the time of his death and subsequently completed by actor Laurence Harvey, who also starred in the film.[4] Peers in the industry, including frequent collaborator James Stewart, expressed shock and paid public tributes to Mann's innovative contributions to film noir and Western genres in the days following his passing.[14]Career

Theater career (1925–1937)

Following high school graduation, Anthony Mann relocated to New York City in 1925 to embark on a professional theater career, initially taking on small acting roles in stock companies and as an understudy on Broadway. Over the next several years, Mann continued building experience through ensemble and supporting parts, honing his foundational skills in performance amid the competitive New York theater scene. By the early 1930s, Mann expanded beyond acting into production roles, serving as an assistant production manager, stage manager, and set designer, while observing esteemed directors like David Belasco, Chester Erskine, and Rouben Mamoulian from the wings. This period of apprenticeship included work with the Red Barn Playhouse on Long Island, where he began directing productions and first encountered future collaborator James Stewart. In 1933, he joined the Theatre Guild as production manager, marking a pivotal step in his professional growth. Mann's directorial debut came that same year with Christopher Morley's Thunder on the Left at Maxine Elliott's Theatre, a production that achieved moderate success and ran for about a month.[15] He followed this in 1936 with So Proudly We Hail, another Theatre Guild staging that enjoyed reasonable public reception over a limited run.[16] Through these assistant and directing positions, Mann developed core techniques in stage management, set design, and narrative pacing, gaining exposure to emerging influences like psychological realism in performance that would later inform his filmmaking approach.Hollywood transition and early directing (1937–1946)

In 1937, following his theater work in New York, Anthony Mann relocated to Hollywood, where he was hired by producer David O. Selznick as a talent scout and casting director at Selznick International Pictures.[8] In this role, Mann directed screen tests for major productions, including Gone with the Wind (1939) and Rebecca (1940), which helped him build connections within the industry that would later influence his collaborations.[8] These early positions allowed him to transition from stage to screen, gaining insight into film production while scouting talent for Selznick's prestigious projects. By the early 1940s, Mann advanced to assistant director at Paramount Pictures, contributing to films such as Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels (1941).[8] This experience honed his understanding of on-set dynamics and narrative pacing, preparing him for his directorial debut. During this period, he also engaged in experimental television directing for NBC's W2XBS station from 1939 to 1940, producing content that, though largely lost today, marked his initial foray into the medium.[13] Additionally, amid World War II, Mann contributed to brief military documentary efforts, further expanding his professional network with individuals who would become key collaborators in his later career.[9] Mann's first credited feature as director was the B-movie Dr. Broadway (1942), a lighthearted Paramount programmer starring Macdonald Carey as a physician navigating New York nightlife, which showcased his ability to handle ensemble casts and urban settings on a modest budget.[8] He followed this with other low-budget features, including My Best Gal (1944) at Universal, a comedy about a young woman (Jane Withers) staging a show to win back her fiancé, demonstrating his versatility in musical and romantic genres despite production constraints.[8] These early efforts, often classified as programmers, allowed Mann to experiment with visual storytelling and character-driven plots, laying foundational skills for his subsequent work in more ambitious films.Film noir breakthrough (1947–1949)

Anthony Mann's breakthrough in film noir came with T-Men (1947), a taut semi-documentary thriller produced by Eagle-Lion Films that showcased his emerging mastery of tension and realism. The film follows two U.S. Treasury agents, Dennis O'Brien and Anthony Genaro (played by Dennis O'Keefe and Alfred Ryder), who go undercover to dismantle a counterfeiting ring operating between Detroit and Los Angeles, blending procedural authenticity with shadowy underworld intrigue. Themes of corruption and moral ambiguity permeate the narrative, as the agents increasingly adopt the brutal tactics of the criminals they infiltrate, blurring the line between law enforcement and criminality. This docudrama style, inspired by earlier films like The House on 92nd Street (1945), incorporated on-location shooting in Detroit, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., along with newsreel-like voiceover narration by Reed Hadley to heighten verisimilitude. Mann's collaboration with cinematographer John Alton marked a pivotal evolution in his visual style; Alton's high-contrast black-and-white photography, featuring low-angle shots and dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, created a mood of inescapable peril and psychological strain, as Alton himself noted, "I used light for mood." Critically, T-Men was praised for its realistic pacing and authenticity, with New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther highlighting its "look of reality" that distinguished it from more stylized noirs. The film proved a major box-office success, grossing over $2 million against a $434,000 budget, making it Eagle-Lion's top earner and establishing Mann as a director capable of delivering profitable genre films.[17] Building on this momentum, Mann directed Raw Deal (1948), another Eagle-Lion production that intensified his exploration of postwar fatalism and entrapment within the noir genre. The story centers on convict Joe Sullivan (O'Keefe), who escapes prison with the aid of his loyal girlfriend Pat (Claire Trevor) and navigates a treacherous alliance with sadistic gangster Rick Coyle (Raymond Burr), all while evading capture in a fog-shrouded urban landscape. Corruption and moral ambiguity drive the plot, as Joe's quest for revenge exposes the inescapable cycle of violence and betrayal, underscored by Pat's rare female voiceover narration that adds a layer of introspective doom. Alton's cinematography again dominates, employing extreme low-key lighting, slow dolly shots, and motifs of nets and iron bars to symbolize psychological confinement, transforming the film into a visceral portrait of "urban hell." Mann's pacing—clipped and relentless in its 79-minute runtime—earned acclaim for its raw intensity, with film historian Wheeler Winston Dixon describing it as one of Mann's "most enduring visions." The picture capitalized on T-Men's success, achieving strong box-office returns that solidified Mann's reputation for low-budget thrillers with high emotional stakes.[18] Mann's noir phase culminated with Border Incident (1949), his first film for MGM, which expanded the docudrama format to address cross-border exploitation while maintaining the genre's signature grit. Co-written by John C. Higgins, the narrative tracks two undercover agents—one American (George Murphy) and one Mexican (Ricardo Montalbán)—investigating a ruthless ring smuggling and enslaving bracero workers along the U.S.-Mexico border, culminating in stark depictions of human trafficking and brutality. Themes of institutional corruption and ethical compromise are central, as the agents witness and participate in moral atrocities to expose a system profiting from desperation. Retaining the semi-documentary approach with authoritative narration and location filming in California's Imperial Valley, the film integrates Alton's chiaroscuro mastery to stunning effect, creating a bridge between urban noir shadows and expansive, unforgiving terrain—hailed as their greatest collaboration for its visual integration of light and landscape. Critics lauded its shocking realism and taut suspense, with the film's violent sequences and social commentary marking a step toward Mann's later thematic depths. As MGM's modestly budgeted entry, Border Incident performed solidly at the box office, demonstrating Mann's versatility with larger resources and paving the way for higher-profile assignments by proving his command of pacing and genre innovation.[8]Western collaborations (1950–1958)

Anthony Mann's Western period from 1950 to 1958 marked a significant evolution in his career, characterized by collaborations that infused the genre with psychological depth and moral ambiguity, drawing on his earlier film noir sensibilities to explore character introspection in frontier settings.[19] This era began with Devil's Doorway (1950), a stark examination of racial prejudice and land rights through the story of Lance Poole (Robert Taylor), a Shoshone Civil War veteran who returns home to face betrayal and violence over his ranch in Wyoming's Sweet Meadows valley. The film allegorizes post-World War II assimilationist policies and civil rights struggles, portraying Poole's fight for re-integration as a tragic disintegration amid systemic bigotry. Mann's partnership with James Stewart produced five landmark Westerns that redefined the genre's heroic archetype, shifting Stewart from the affable everyman of earlier roles to obsessive, flawed protagonists grappling with vengeance and redemption. Winchester '73 (1950) launched this collaboration, with Stewart as Lin McAdam, a gunfighter consumed by revenge against his brother's killer, using the titular rifle as a symbol of destructive obsession that echoes acts of violence throughout the narrative.[20] In Bend of the River (1952), Stewart's character, Glyn McLyntock, leads settlers westward but confronts betrayal and moral compromise, highlighting themes of loyalty tested by greed in the Oregon Territory.[19] The Far Country (1954) continued this vein, with Stewart as Tom Destry, a cattle driver in Alaska facing corruption and lawlessness, where personal gain clashes with communal ideals amid the Klondike gold rush. These films introduced anti-Western elements, portraying the frontier not as a site of noble expansion but of personal and societal cynicism, where violence stems from inner turmoil rather than external heroism.[20] The collaboration deepened with The Naked Spur (1953) and The Man from Laramie (1955), emphasizing Stewart's anti-heroes as self-doubting figures whose quests for justice reveal crippling neuroses. In The Naked Spur, bounty hunter Howard Kemp (Stewart) pursues a killer through Colorado's harsh landscapes, his aggression mirroring the brutality he seeks to punish, ultimately finding partial redemption through human connections amid the ordeal.[19] Similarly, The Man from Laramie features Will Lockhart (Stewart) seeking retribution for his brother's death, entangled in a web of corruption and family vendettas in New Mexico, where moral complexity forces confrontations with villains who reflect the hero's own flaws.[19] Stewart's performances in these films exhibit a "pent-up aggression that seems to broaden... into something like pleasure," transforming the Western hero into a psychologically complex figure driven by obsession.[20] Outside the Stewart series, The Last Frontier (1956), also known as Savage Wilderness, explored military duty and interpersonal conflict during the Civil War era, with Victor Mature as trapper Jed Cooper clashing with a ruthless Army colonel (Robert Preston) at a remote frontier outpost threatened by Native American forces.[21] The film underscores themes of loyalty, religion, and the blurred lines between civilization and savagery, using the wilderness as a metaphor for internal moral battles without Stewart's star power, resulting in a more ensemble-driven narrative.[21] Overall, Mann's 1950s Westerns innovated by subverting genre conventions, applying noir-like introspection to depict revenge arcs as paths to potential redemption while critiquing the myth of the unblemished frontier.[19]Widescreen epics (1959–1964)

In the late 1950s, Anthony Mann transitioned to grand-scale historical epics, leveraging emerging widescreen technologies to depict sweeping narratives of heroism and empire. His first major venture in this vein was El Cid (1961), a lavish production centered on the 11th-century Spanish warrior Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, who navigates political betrayals and Moorish invasions to unify Christian Spain. The film features intense epic battles, such as the climactic siege of Valencia, alongside intricate court intrigues involving royal ambitions and forbidden romance. Shot primarily on location in Peñíscola, Spain, El Cid starred Charlton Heston as the titular hero and Sophia Loren as his devoted wife Chimène, marking a key collaboration that infused the project with star power and dramatic tension.[22][23] Technically ambitious, El Cid employed Super Technirama 70, a 70mm process that delivered a 2.2:1 aspect ratio for immersive widescreen vistas, captured by cinematographer Robert Krasker using modified three-strip Technicolor cameras to enhance the scale of battle sequences and rugged landscapes. With a budget of $7 million, the production mobilized 1,700 soldiers for crowd scenes and thousands of custom costumes, though it encountered logistical hurdles from on-site filming and script revisions contributed by Heston and Mann himself. Critics lauded the film's spectacle and energy in its action set pieces but found the political intrigue somewhat muddled and the character depth lacking, prioritizing visual grandeur over nuanced moral exploration.[22][23] Mann's follow-up, The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), escalated the scope to examine the decline of the ancient world through the lens of Marcus Aurelius' successor Commodus, blending colossal battles—like the fiery Danube campaign—with themes of imperial corruption and philosophical governance. Again starring Heston as the loyal general Livius and Loren as the emperor's daughter Lucilla, the film delved into political machinations, including Commodus' tyrannical rise and the empire's internal decay, drawing loose inspiration from Edward Gibbon's histories. Filmed at Samuel Bronston's Madrid studios with a full-scale replica of the Roman Forum, it utilized Ultra Panavision 70 for 70mm presentations, allowing expansive compositions that echoed Mann's earlier use of landscapes to convey moral ambiguity.[24][25][26] Despite its technical prowess, The Fall of the Roman Empire faced severe production challenges, including a ballooning $19 million budget that strained resources and led to Bronston's bankruptcy after the film's release. Presented in roadshow engagements to showcase its widescreen spectacle, it initially bombed at the box office, grossing only about $4.75 million amid audience fatigue with historical epics. While contemporary reviewers dismissed it as overly ponderous, later assessments have praised its intelligent handling of historical themes and visual artistry, though noting inaccuracies in depicting Roman politics and religion. Mann's widescreen epics thus represented a bold but uneven pivot, carrying over his Western-era emphasis on vast terrains to symbolize human frailty.[24][25][26]Later films (1965–1967)

In the mid-1960s, Anthony Mann directed The Heroes of Telemark (1965), his last fully completed feature, a British-Norwegian war film produced by Benton Film Productions and distributed by Columbia Pictures. The story dramatizes the real-life Operation Gunnerside, in which Norwegian resistance fighters, led by figures inspired by scientists and commandos, sabotaged a Nazi-controlled heavy water facility at Vemork to hinder Germany's atomic bomb program during World War II. Starring Kirk Douglas as the physicist Rolf Pedersen and Richard Harris as the commando Knut Straud, the film incorporates tense action sequences, including ski chases through snowy terrains, and emphasizes themes of sacrifice and moral resolve amid occupation. Shot on location in Norway despite harsh winter conditions, it represented Mann's continued interest in large-scale historical conflicts, building on his experience with epic productions while adapting to a more focused wartime narrative.[27][28] Mann's attempt to transition into contemporary genres came with A Dandy in Aspic (1968), a Cold War spy thriller set in London and Berlin, produced by Anthony Mann Productions and Columbia Pictures. Based on Derek Marlowe's novel, the film follows Alexander Eberlin (Laurence Harvey), a British intelligence officer secretly working as a Soviet double agent, exploring identity, deception, and espionage intrigue amid East-West tensions. This project marked Mann's shift toward modern thriller elements, diverging from his earlier Westerns and historical epics to engage with the era's spy boom, as seen in films like those from the James Bond series. However, production was plagued by issues, including script revisions and logistical challenges during Berlin location shooting.[8][29] Mann's declining health culminated in a fatal heart attack on April 29, 1967, while filming A Dandy in Aspic in Berlin, leaving the project unfinished after principal photography was well underway. At age 60, he had been dealing with physical strain from prior demanding shoots, exacerbating conflicts with producers over creative control and reshoots. Laurence Harvey stepped in as uncredited co-director to complete the film, using existing footage and additional scenes, which contributed to its uneven tone and narrative inconsistencies. These production disruptions highlighted the toll of Mann's rigorous schedule and the industry's pressures on aging directors transitioning genres.[8][30][31] Retrospectively, Mann's 1965–1967 films are lesser-known entries in his filmography, often critiqued as commercial disappointments compared to his noir and Western peaks, yet they underscore his adaptability in experimenting with war adventures and Cold War espionage amid career fatigue. The Heroes of Telemark is noted for its solid action and historical basis, while A Dandy in Aspic reveals Mann's intent to probe psychological complexity in spy narratives, even if compromised by circumstance. Together, they reflect a director's resilience in navigating studio demands and genre evolution during a period of personal and professional strain.[31][8]Artistic style

Antiheroes and moral complexity

Anthony Mann's films frequently featured protagonists who deviated from traditional heroic ideals, embodying antiheroes driven by personal obsessions and entangled in ethical quandaries. These characters, often marked by inner turmoil and questionable motives, reflected the director's interest in human frailty and the blurred lines between right and wrong, a theme pervasive in both his film noirs and Westerns.[32] In his Westerns, Mann crafted obsessive avengers as central archetypes, portraying men whose quests for justice or retribution come at the expense of their own humanity. James Stewart's portrayal of Howard Kemp in The Naked Spur (1953) exemplifies this, as the bounty hunter relentlessly pursues a fugitive, only to confront the moral cost of his greed and isolation in a climactic monologue where he laments the erosion of his principles amid betrayal and violence. Similarly, in Winchester '73 (1950), Stewart's Lin McAdam embodies vengeful fixation, his pursuit of a stolen rifle—and the brother who killed his father—unfolds through a pantomimed duel scene that underscores the psychological toll of unresolved trauma, denying any tidy redemption. These figures, influenced by post-World War II disillusionment with heroism, navigate moral ambiguity without clear resolution, their victories tainted by self-inflicted wounds that highlight the futility of personal vendettas.[32] Mann's film noirs extended this complexity to institutional corruption and flawed authority figures, often drawing from the era's societal unease. In T-Men (1947), the undercover Treasury agents infiltrate a counterfeiting ring, but the narrative probes the ethical erosion required for such deception, with characters like Dennis O'Keefe's Arvak embodying the antiheroic strain of lawmen who must adopt criminal personas, risking their integrity in shadowy interrogations and betrayals that blur the divide between enforcers and lawbreakers. Border Incident (1949) further explores this through corrupt border officials and smugglers exploiting migrant workers, presenting protagonists like George Murphy's undercover agent as morally compromised participants in a system rife with exploitation; a key scene in the irrigation ditch ambush reveals the visceral consequences of their vigilante justice, questioning the righteousness of state-sanctioned violence without offering absolution. This post-war cynicism permeates Mann's noirs, where protagonists grapple with dilemmas that expose the hollowness of authority and the inescapable cycle of moral decay.[33][17]Landscapes and visual motifs

In Anthony Mann's Western films, natural landscapes often serve as more than mere backdrops, functioning as active elements that mirror characters' internal conflicts and amplify themes of isolation and turmoil. In The Man from Laramie (1955), the stark formations of Monument Valley are depicted not as idyllic symbols but as a harsh battleground that underscores the protagonist's psychological isolation and vengeful drive, with towering rock spires emphasizing his solitary confrontation with moral ambiguity.[20] Similarly, the unforgiving deserts in Border Incident (1949) evoke a sense of desolation and entrapment, where the expansive, barren terrain merges with the characters' precarious positions, heightening the tension of border-crossing exploitation and human vulnerability.[33] These rugged environments transform the Western frontier into a space of relentless adversity, reinforcing the genre's psychological depth.[34] Mann's film noir works, by contrast, utilize urban settings to cultivate paranoia and confinement, with shadowy cityscapes acting as labyrinthine motifs that blur boundaries between safety and threat. In films like T-Men (1947) and Raw Deal (1948), nocturnal streets and enclosed alleys—photographed with high-contrast lighting by John Alton—create abstract, alienating landscapes that isolate protagonists amid societal distrust, evoking a pervasive sense of surveillance and betrayal.[34] Motifs of borders and frontiers recur here as well, not in open deserts but in the liminal zones of urban underbelly, such as the foggy waterfronts in Border Incident, where the U.S.-Mexico divide symbolizes ideological and economic divides, intensifying the protagonists' precarious undercover existence.[33] These city environments, often rendered in claustrophobic interiors with geometric shadows, amplify the antiheroes' moral isolation by trapping them in visually oppressive spaces.[34] Over the course of his career, Mann's visual approach evolved from the tight, shadowy enclosures of his noir period to the sweeping vistas of his widescreen epics, reflecting a shift toward grandeur while retaining thematic motifs of human struggle against vast forces. In later films like El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), expansive Mediterranean and mountainous landscapes—captured in CinemaScope—provide a sense of epic scale, yet they continue to symbolize isolation through their overwhelming immensity, dwarfing individual figures and echoing the inner turmoil of earlier works.[35] This progression highlights Mann's adeptness at using environment to heighten narrative tension, transitioning from urban paranoia to monumental frontiers that test human resilience.[13]Directorial techniques

Anthony Mann's editing rhythms varied by genre and narrative intent, often employing rapid cuts to heighten the intensity of action sequences while favoring longer takes to build suspense in his film noirs. In works like Border Incident (1949), he utilized discontinuous editing to disorient viewers and underscore hostile interpersonal dynamics, creating a fragmented visual rhythm that mirrored the characters' precarious situations.[8] This approach contrasted with the more fluid, extended shots in his later Westerns, where sustained takes allowed for deliberate pacing amid expansive landscapes, as seen in The Naked Spur (1953).[36] Such techniques evolved from his early noir phase, where quick intercuts amplified procedural urgency in films like T-Men (1947).[37] In casting, Mann demonstrated a keen eye honed from his pre-directing role as a talent scout and casting director for David O. Selznick, where he oversaw screen tests for landmark productions such as Gone with the Wind (1939).[8] He preferred actors capable of nuanced, internalized performances, drawing from his theater background to select performers who could sustain emotional depth across scenes, often fostering long-term partnerships that enhanced his films' authenticity. A prime example was his repeated collaboration with James Stewart in seven projects from 1950 onward, leveraging the actor's versatility to portray complex, tormented figures.[8] Similarly, his work with cinematographer John Alton spanned five films, including T-Men (1947), Raw Deal (1948), He Walked by Night (1948, uncredited), Reign of Terror (1949), and Border Incident (1949), where Alton's shadowy lighting complemented Mann's rhythmic editing to define the visual style of post-war noir.[38] Mann's production approach emphasized location shooting to ground his narratives in authentic environments, a shift that became pronounced in his Westerns and distinguished his work from studio-bound contemporaries. Films like Side Street (1950) were largely filmed on New York City streets to capture urban grit, while The Naked Spur (1953) utilized rugged Colorado terrain for twelve days of on-site shooting despite challenging weather, prioritizing realism over controlled sets.[36][39] This method extended to his epics, such as El Cid (1961), shot across Spain for immersive scale.[8] Influenced by his theater origins at the Theater Guild, Mann adapted stage pacing to cinema by blending static, tableau-like compositions—reminiscent of theatrical blocking—with film's dynamic montage, allowing for tighter narrative flow while retaining dramatic tension.[8][32]Legacy

Critical reception and influence