Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Serial film

View on Wikipedia

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2024) |

A serial film, film serial (or just serial), movie serial, or chapter play, is a motion picture form popular during the first half of the 20th century, consisting of a series of short subjects exhibited in consecutive order at one theater, generally advancing weekly, until the series is completed. Usually, each serial involves a single set of characters, protagonistic and antagonistic, involved in a single story. The film is edited into chapters, after the fashion of serial fiction, and the episodes should not be shown out of order, as individual chapters, or as part of a random collection of short subjects.

Each chapter was screened at a movie theater for one week, and typically ended with a cliffhanger, in which characters found themselves in perilous situations with little apparent chance of escape. Viewers had to return each week to see the cliffhangers resolved and to follow the continuing story. Movie serials were especially popular with children, and for many youths in the first half of the 20th century a typical Saturday matinee at the movies included at least one chapter of a serial, along with animated cartoons, newsreels, and two feature films.

There were films covering many genres, including crime fiction, espionage, comic book or comic strip characters, science fiction, and jungle adventures. Many serials were Westerns, since those were the least expensive to film. Although most serials were filmed economically, some were made at significant expense. The Flash Gordon serial and its sequels, for instance, were major productions in their times. Serials were action-packed stories that usually involved a hero (or heroes) battling an evil villain and rescuing a damsel in distress. The villain would continually place the hero into inescapable death traps, or the heroine would be placed into a lethal peril and the hero would come to her rescue. The hero and heroine would face one trap after another, battling countless thugs and henchmen, before finally defeating the villain.

History

[edit]- List of film serials by year

Birth of the form

[edit]Movie serials began in Europe. In France Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset launched his series of Nick Carter films in 1908, and the idea of the episodic crime adventure was developed particularly by Louis Feuillade in Fantômas (1913–14), Les Vampires (1915), and Judex (1916); in Germany, Homunculus (1916), directed by Otto Rippert, was a six-part horror serial about an artificial creature.

There were also the 1910 Deutsche Vitaskop five-episode Arsene Lupin Contra Sherlock Holmes, based upon the Maurice LeBlanc novel,[1] and a possible but unconfirmed Raffles serial in 1911.[2]

American serials

[edit]Serials in America first came about in 1912, as extensions of magazine and newspaper stories. Publishers realized they could build interest (and boost circulation) by sponsoring live-action adventures of the printed characters, serialized like the printed counterparts. The first screen adaptation was What Happened to Mary. produced by the Edison studio and coinciding with the adventure stories published in The Ladies' World. It may be significant that the early American serials were aimed at the feminine audience who wanted thrills, not the masculine audience who preferred more extreme, blood-and-thunder action. By the 1930s and the advent of sound films, both markets ultimately devolved to the juvenile audience, although serials continued to command a certain adult following.

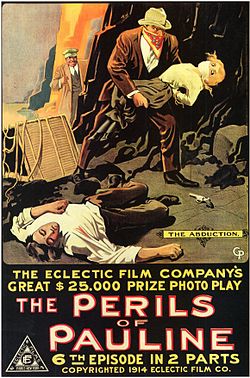

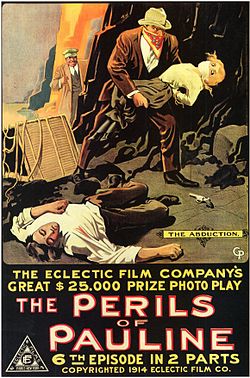

The most famous American serials of the silent era include The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine made by Pathé Frères and starring Pearl White. Another popular serial was the 119-episode The Hazards of Helen made by Kalem Studios and starring Helen Holmes for the first 48 episodes, then Helen Gibson for the remainder. Ruth Roland, Marin Sais, Grace Cunard, and Ann Little were also early leading serial queens. Other major studios of the silent era, such as Vitagraph and Essanay Studios, produced serials, as did Warner Bros., Fox, and Universal. Several independent companies (for example, Mascot Pictures) made Western serials. Four silent Tarzan serials were also made.

Sound era

[edit]

Expensive feature films were offered by exhibitors for a percentage of the theaters' admissions. Serials, however, were rented by exhibitors for a much lower, flat fee. The arrival of sound technology made it costlier to produce serials, so that they were no longer as profitable on a flat rental basis. Further, the stock market crash of 1929 and the added expense of sound equipment made it impossible for many of the smaller companies that produced serials to upgrade to sound, and they went out of business. Mascot Pictures, which specialized in serials, made the transition from silent to sound and produced the first "talking" serial, King of the Kongo (1929). Universal Pictures also kept its serial unit alive through the transition.

In the early 1930s a handful of independent companies tried their hand at making serials. The Weiss Brothers had been making serials in 1935 and 1936. In 1937 Columbia Pictures, inspired by the previous year's serial blockbuster success at Universal, Flash Gordon, decided to enter the serial field and contracted with the Weiss Brothers (as Adventure Serials Inc.) to make four chapter plays. They were successful enough that Columbia canceled the agreement after three productions[3] and produced the fourth itself, using its own staff and facilities. Columbia thus forced the Weiss Bros. out of the serial field.

Mascot Pictures was absorbed by Republic Pictures, so that by 1937, serial production was now in the hands of three companies – Universal, Columbia, and Republic. Each company had its own following: Republic was known for its well staged action scenes and spectacular cliffhanger endings; Universal broadened its serials' appeal by casting stars of feature films; Columbia specialized in screen adaptations of radio, comic-book, and detective-fiction adventures.

These studios turned out four serials per year (one each season) of 12 to 15 episodes each, a pace they all kept up until the end of World War II. In 1946, new management at Universal did away with all low-budget productions including "B" musicals, mysteries, westerns, and serials,[4] Republic and Columbia continued unchallenged. Republic's serials ran for 12, 13, 14, or 15 chapters; Columbia's ran a standard 15 episodes (with the single exception of Mandrake the Magician, which ran 12 episodes).

By the mid-1950s, however, episodic television series and the sale of older serials to TV syndicators, together with the gradual drop in audience attendance at Saturday matinees in general, made serial production a losing proposition.

Production

[edit]Peak form

[edit]

The classic sound serial, particularly in its Republic format, has a first episode of three reels (approximately 30 minutes in length) and begins with reports of a masked, secret, or unsuspected villain menacing an unspecific part of America. This episode traditionally has the most detailed credits at the beginning, often with pictures of the actors with their names and that of the character they play. Often there follows a montage of scenes lifted from the cliffhangers of previous serials to depict the ways in which the master criminal was a serial killer with a motive. In the first episode, various suspects or "candidates" who may, in secret, be this villain are presented, and the viewer often hears the voice but does not see the face of this mastermind commanding his lieutenant (or "lead villain"), whom the viewer sees in just about every episode.

In the succeeding weeks (usually 11 to 14), an episode of two reels (approximately 20 minutes) was presented, in which the villain and his henchmen commit crimes in various places, fight the hero, and trap someone to make the ending a cliffhanger. Many of the episodes have clues, dialogue, and events leading the viewer to think that any of the candidates were the mastermind. As serials were made by writing the whole script first and then slicing it into portions filmed at various sites, often the same location would be used several times in the serial, often given different signage, or none at all, just being referred to differently. There would often be a female love interest of the male hero, or a female hero herself, but as the audience was mainly youngsters, there was no romance.

The beginning of each chapter would bring the story up to date by repeating the last few minutes of the previous chapter, and then revealing how the main character escaped. Often the reprised scene would add an element not seen in the previous episode, but unless it contradicted something shown previously, audiences accepted the explanation. On rare occasions the filmmakers would depend on the audience not remembering details of the previous week's chapter, using alternate outcomes that did not exactly match the previous episode's cliffhanger.

The last episode was sometimes a bit longer than most, for its tasks were to unmask the head villain (who usually was someone completely unsuspected), wrap up the loose ends, and end with the victorious principals relieved of their perils.

In 1936, Republic standardized the "economy episode" (or "recap chapter") in which the characters summarize or reminisce about their adventures, so as to introduce showing those scenes again (in the manner of a clip show in modern television). Serials had been including older scenes for years, as flashbacks during later parts of the narrative, but the wholesale insertion of entire sequences was introduced in the 1936 outdoor serial Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island. It was scheduled as a standard 12-chapter adventure, but when bad weather on location delayed the filming, writer Barry Shipman was forced to come up with two extra chapters to justify the added expense. This was an emergency measure at the time, but Republic recognized that it did save money, so the recap chapter became standard practice in almost all of its ensuing serials. Recap chapters had lower budgets, so rather than staging an elaborate cliffhanger (a runaway vehicle, a stampede, a flooding chamber, etc.), a cheaper, simpler cliffhanger would be employed (an explosion, someone knocked unconscious, etc.).

Production practices

[edit]The major studios had their own retinues of actors and writers, their own prop departments, existing sets, stock footage, and music libraries. The early independent studios had none of these, but could rent sets from independent producers of western features.

The firms saved money by reusing the same cliffhangers, stunt and special-effects sequences over the years. Mines or tunnels flooded often, even in Flash Gordon (reusing spectacular flood footage from Universal's 1927 silent drama Perch of the Devil) and the same model cars and trains went off the same cliffs and bridges. Republic had a Packard limousine and a Ford Woodie station wagon used in serial after serial so they could match the shots with the stock footage from the model or previous stunt driving. Three different serials had them chasing the Art Deco sound truck, required for location shooting, for various reasons. Male fistfighters usually wore hats so that the change from actor to stunt double would not be caught so easily. A rubber liner on the hatband of the stuntman's fedora would fit snugly on the stuntman's head, so the hat would stay on during fight scenes.

Many serials were later cut down and edited into feature versions for theatrical release or for television. Tarzan the Fearless (1933) and The Return of Chandu (1934) were released in a hybrid format that allowed exhibitors to show a feature version of the first four chapters before continuing the story in weekly instalments.[5]

Recaps of the story

[edit]Each serial chapter began with exposition of what led up to the previous episode's cliffhanger. Each studio approached this in different ways. Universal had been using printed title cards to introduce each chapter until 1938, when it began using "scrolling text" , a format George Lucas used in the Star Wars films. In 1942 Universal scrapped the printed recaps altogether in what the studio called "streamlined serials". The action began immediately, with the story characters discussing the action leading up to the cliffhanger.

Republic followed the traditional format established by its predecessor Mascot, with still photos of the story characters accompanied by printed recaps of the narrative.

Columbia used spoken recaps through 1939, replaced by printed recaps in 1940. Announcer Knox Manning was hired in 1940 to read along with the printed recaps until 1942, when only Manning's voice was used to summarize the action.

Stylistic differences between the studios

[edit]Universal had been making serials since the 1910s, and continued to service its loyal neighborhood-theater customers with four serials annually. The studio made news in 1929 by hiring Tim McCoy to star in its first all-talking serial, The Indians Are Coming! Epic footage from this western serial turned up again and again in later serials and features. In 1936 Universal scored a coup by licensing the comic-strip character Flash Gordon for the screen; the serial was a smash hit, and was even booked into first-run theaters that usually did not bother with chapter plays. Universal followed it up with more pop-culture icons: The Green Hornet and Ace Drummond from radio, and Smilin' Jack and Buck Rogers from newspapers. Universal was more story-conscious than the other studios, and cast its serials with "name" actors recognizable from feature films: Lon Chaney Jr., Béla Lugosi, Dick Foran, The Dead End Kids, Kent Taylor, Buck Jones, Ralph Morgan, Milburn Stone, Robert Armstrong, Irene Hervey, and Johnny Mack Brown, among many others.

In the 1940s Universal's serials employed urban and/or wartime themes, incorporating newsreel footage of actual disasters. The 1942 serial Gang Busters is perhaps the best of Universal's urban serials; Universal often reused some of its footage for future serials. Don Winslow of the Navy was a popular, patriotic serial. The studio's reliance on stock footage for the big action scenes -- some of it silent footage dating back to the 1920s -- was certainly economical, but it often hurt the overall quality of the films. Universal's last serial was The Mysterious Mr. M (1946), and the serial unit shut down.

Republic was the successor to Mascot Pictures, a serial specialist. Writers and directors were already geared to staging exciting films, and Republic improved on Mascot, adding music to underscore the action, and staging more elaborate stunts. Republic was one of Hollywood's smaller studios, but its serials have been hailed as some of the best, especially those directed by John English and William Witney. In addition to solid screenwriting that many critics thought was quite accomplished, the firm also introduced choreographed fistfights, which often included the stuntmen (usually the ones portraying the villains, never the heroes) throwing things in desperation at one another in every fight to heighten the action. Republic serials are noted for outstanding special effects, such as large-scale explosions and demolitions, and the more fantastic visuals like Captain Marvel and Rocketman flying. Most of the trick scenes were engineered by Howard and Theodore Lydecker. Republic bought the screen rights to the newspaper comic character Dick Tracy, the radio character The Lone Ranger, and the comic-book characters Captain America, Captain Marvel, and Spy Smasher.

Republic's serial scripts were written by teams, usually from three to seven writers. From 1950 Republic economized on serial production. The studio was no longer licensing expensive radio and comic-strip characters, and no longer staging spectacular action sequences. To save money, Republic turned instead to its impressive backlog of action highlights, which were cleverly re-edited into the new serials. The studio slashed costs further by shortening the length of each chapter from 1800 feet (20 minutes) to 1200 feet (13 minutes, 20 seconds). Most of the studio's serials of the 1950s were written by only one man, Ronald Davidson—Davidson had co-written and produced many Republic serials, and was familiar enough with the film library to write new scenes based on the older action footage. Republic's last serial was King of the Carnival (1955), a reworking of 1939's Daredevils of the Red Circle using some of its footage.

Columbia made several serials using its own staff and facilities (1938–1939 and 1943–1945), and these are among the studio's best efforts: The Spider's Web, The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok, Batman, The Secret Code, and The Phantom maintained Columbia's own high standard. However, Columbia's serials often have a reputation for cheapness, because the studio usually subcontracted its serial production to outside producers: the Weiss Brothers (1937–1938), Larry Darmour (1939–1942), and finally Sam Katzman (1945–1956). Columbia built many serials around name-brand heroes. From newspaper comics, they got Terry and the Pirates, Mandrake the Magician, The Phantom, and Brenda Starr, Reporter; from the comic books, Blackhawk, Congo Bill, time traveler Brick Bradford, and Batman and Superman (although this last owed more to its radio incarnation, which the credits acknowledged); from radio, Jack Armstrong and Hop Harrigan; from the hero pulp characters like The Spider (two serials: The Spider's Web and The Spider Returns) and The Shadow (despite also being a popular radio series); from the British novelist Edgar Wallace, the first archer-superhero, The Green Archer; and even from television: Captain Video.

Columbia's early serials were very well received by audiences—exhibitors voted The Spider's Web (1938) the number-one serial of the year.[6] Former silent-serial director James W. Horne co-directed The Spider's Web, and his work secured him a permanent position in Columbia's serial unit. Horne had been a comedy specialist in the 1930s, often working with Laurel and Hardy, and most of his Columbia serials after 1939 are played tongue-in-cheek, with exaggerated villainy and improbable heroics (the hero takes on six men in a fistfight and wins). After Horne's death in 1942, the studio's serial output was somewhat more sober, but still aimed primarily at the juvenile audience. Batman (1943) was quite popular, and Superman (1948) was phenomenally successful despite using cartoon animation for the flying sequences instead of more expensive special effects.

Spencer Gordon Bennet, veteran director of silent serials, left Republic for Columbia in 1947. He directed or co-directed the studio's later serials. In 1954 producer Sam Katzman, whose budgets were already low, reduced them even more on serials. The last four Columbia serials were very-low-budget affairs, consisting mostly of action scenes and cliffhanger endings from older productions, and even employing the same actors for new scenes tying the old footage together. The new footage was so threadbare that it would often show the new hero watching the action from a distance, rather than actually participating in it. Columbia outlasted the other serial producers, its last being Blazing the Overland Trail (1956).

Availability

[edit]In theaters

[edit]There was always a market for action subjects in theaters, so as far back as 1935 independent film companies reissued older serials for new audiences. Universal brought back its Flash Gordon serials, and reissue distributors Film Classics and Realart re-released other Universal serials in the late 1940s. Both Republic and Columbia began re-releasing their older serials in 1947 as a cost-cutting measure: instead of making four new serials annually, the studios could now make three, and the fourth would be a reprint of an old serial.

Although Republic discontinued new serial production in 1955, the studio continued making older ones available to theaters through 1959. Columbia, which canceled new serials in 1956, kept older ones in circulation until 1966. Columbia still offers a handful of serials to today's theaters.

On television

[edit]Serials, with their short running times and episodic format, were very attractive to programmers in the early days of television. Veteran producers Louis Weiss and Nat Levine were among the first to offer their serials for broadcast.

The traditional week-to-week format of viewing serials was soon abandoned. As Republic executive David Bloom explained, "Attempts to program serials with full week intervals between chapters during the earlier days of television just about killed them off as effective sales product. It is understandable that this practice was adopted in view of their success in theaters on a Saturday matinee exhibition policy. But cliffhangers simply cannot be treated on TV as they were in theaters and still maintain the suspense so vital to their entertainment content. This suspense factor is diluted by the vast amount of other TV entertainment beamed between weekly showings."[7] TV stations began showing serials daily, generally on weekday afternoons, as children's programming.

In July 1956 TV distributor Serials Inc., a subsidiary of Jerry Hyams's Hygo Television Films, bought the 1936-1946 Universal serials (including all titles, rights, and interests) for $1,500,000.[8] Also in 1956, Columbia's TV subsidiary Screen Gems reprinted many of its serials for broadcast syndication. Only the films' endings were changed: Screen Gems replaced the "at this theater next week" title card with its standard Screen Gems logo. Screen Gems acquired the Hygo company in December 1956,[9] and packaged both Columbia and Universal serials for broadcast.[10] Republic's TV division, Hollywood Television Service, issued serials for television in their unedited theatrical form, as well as in specially edited six-chapter, half-hour editions ready made for TV time slots.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, serials were often revived on BBC television in the United Kingdom.[11]

Home movies

[edit]Both Republic and Columbia issued "highlights" versions of serials for the home-movie market. These were printed on 8mm silent film (and later Super 8 film) and sold directly to owners of home-movie projectors. Columbia was first to market, with three abbreviated chapters from its 1938 serial The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok. When Batman became a national craze in 1965, Columbia issued a six-chapter silent version of its 1943 Batman. Republic followed suit with condensed silent versions of its own serials, including Adventures of Captain Marvel, G-Men vs. the Black Dragon, and Panther Girl of the Kongo.

With the rise in popularity of Super 8 sound-film equipment in the late 1970s, Columbia issued home-movie prints of entire 15-chapter serials, including Batman and Robin, Congo Bill, and Hop Harrigan. These were in print only briefly, until the studios turned away from home-movie films in favor of home video.

Home video

[edit]Film serials released to the home video market from original masters include most Republic titles (with a few exceptions, such as Ghost of Zorro)—which were released by Republic Pictures Home Video on VHS and sometimes laserdisc (sometimes under their re-release titles) mostly from transfers made from the original negatives, The Shadow, and Blackhawk, both released by Sony only on VHS, and DVD versions of Flash Gordon, Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars, and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (Hearst), Adventures of Captain Marvel (Republic Pictures), Batman and Batman and Robin (Sony), Superman and Atom Man vs. Superman (Warner).

The Universal serials had been controlled by Serials Inc. until it closed in 1970. The company now known as VCI Entertainment obtained the rights. VCI is offering new Blu-Ray and DVD restorations of many Universal serials, including Gang Busters, Jungle Queen, Pirate Treasure, and three Buck Jones adventures. All of the new VCI releases derive from Universal's 35mm vault elements.

Notable restorations of partially lost or forgotten serials such as The Adventures of Tarzan, Beatrice Fairfax, The Lone Ranger Rides Again, Daredevils of the West, and King of the Mounties have been made available to fans by The Serial Squadron, a home-video concern specializing in action fare.

A gray market for serials also exists. These are unlicensed DVD releases of studio product, deriving from privately owned 16mm prints or even copies of previously released VHS or laserdisc editions. They are sold by various websites and Internet auctions. These DVDs vary between good and poor quality, depending on their source.

Major video companies have made a few serials available in new, restored editions from original prints and negatives. In 2017, Adventures of Captain Marvel became the first serial to be released on Blu-ray.

Amateur/fan efforts

[edit]An early attempt at a low-budget Western serial, filmed in color, was entitled The Silver Avenger. One or two chapters exist of this effort on 16mm film but it is not known whether the serial was ever completed.

The best-known fan-made chapter play is the four-chapter, silent 16mm Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates, made to resemble Republic and Columbia serials of the 1940s and completed in 1966. The plot involved a masked villain named The Master Duper, one of three members of a Film Commission who attempts to steal the only known prints of priceless antique films, and the heroic Captain Celluloid, who wears a costume reminiscent of that of the Black Commando in the Columbia serial The Secret Code and is determined to uncover him. Roles in the serial are played by, among others, film historians and serial fans Alan G. Barbour, Al Kilgore, and William K. Everson.

In the 1980s, serial fan Blackie Seymour shot a complete 15-chapter serial called The Return of the Copperhead.[12] Seymour's only daughter, who operated the camera at the age of 8, attests that as of 2008 the serial was indeed filmed but the raw footage remains in cans, unedited.

In 2001, King of the Park Rangers, a one-chapter sound serial was released by Cliffhanger Productions on VHS video tape in sepia. It concerned the adventures of a Park Ranger named Patricia King and an FBI Agent who track down a trio of killers out to find buried treasure in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. A second ten-chapter serial, The Dangers of Deborah, in which a female reporter and a criminologist fight to uncover the identity of a mysterious villain named The Terror, was released by Cliffhanger Productions in 2008.

In 2006, Lamb4 Productions created its own homage to the film serials of the 1940s with its own serial titled "Wildcat." The story revolves around a super hero named Wildcat and his attempts to save the fictional Rite City from a masked villain known as the Roach. This eight-chapter serial was based heavily on popular super hero serials such as "Batman and Robin," "Captain America," and "The Adventures of Captain Marvel." After its premiere, "Wildcat" was posted on the official Lamb4 Productions YouTube channel for public viewing.[13]

Studio/commercial efforts, cartoons, and spoofery

[edit]The serial format was used with stories on the original run of The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–58), with each chapter running about six to ten minutes. The longer-running dramatic serials included "Corky and White Shadow", "The Adventures of Spin and Marty", "The Hardy Boys: The Mystery of the Applegate Treasure", "The Boys of the Western Sea", "The Secret of Mystery Lake", "The Hardy Boys: The Mystery of Ghost Farm", and The Adventures of Clint and Mac.

Other Disney programs shown on Walt Disney Presents in segments (such as The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh, The Swamp Fox, The Secret of Boyne Castle, The Mooncussers, and The Prince and the Pauper) and Disney feature films (including Treasure Island; The Three Lives of Thomasina; The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men; Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue; and The Fighting Prince of Donegal) edited into segments for television presentation often had a cliffhanger-serial-like feel.

In England, in the 1950s and 60s, low-budget six-chapter serials such as Dusty Bates and Masters of Venus were released theatrically, but these were not particularly well-regarded or remembered.

The greatest number of serialized television programs to feature any single character were those made featuring "the Doctor", the BBC character introduced in 1963. Doctor Who serials would run anywhere from one to twelve episodes and were shown in weekly segments, as had been the original theatrical cliffhangers. Doctor Who was syndicated in the US as early as 1974, but did not gain a following in America until the mid-1980s when episodes featuring Tom Baker reached its shores. Although the series ended in 1989, it was revived in 2005, now following a more standard episode format.

The 1960s cartoon show Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle included two serial-style episodes per program. These spoofed the cliffhanger serial form, with pun-filled teasers for the next episode: "Be with us next time for Cheerful Little Pierful or Bomb Voyage". Within the Rocky and Bullwinkle show, the recurring but non-serialized Dudley Do-Right, specifically parodied the damsel in distress (Nell Fenwick) being tied to railroad tracks by arch villain Snidely Whiplash and rescued by the noble but clueless Dudley. The Hanna–Barbera Perils of Penelope Pitstop (spun off from the Hanna-Barbera hit Wacky Races) was a takeoff on the silent serials The Perils of Pauline and The Iron Claw, which featured Paul Lynde as the voice of the villain Sylvester Sneakley, alias "The Hooded Claw".

Danger Island, a multi-part story in under-10-minute episodes, was shown on the Saturday-morning Banana Splits program in the late 1960s. Episodes were short, full of wild action, and usually ended on a cliffhanger. This serial was directed by Richard Donner and featured the first African American action hero in a chapter play. The violence present in most of the episodes, though much of it was deliberately comical and would not be considered shocking today, also raised concerns at a time when violence in children's TV was at issue.

On February 27, 1979, NBC broadcast the first episode of an hour-long weekly television series Cliffhangers!, which had three segments, each with a different serial: a horror story (The Curse of Dracula, starring Michael Nouri), a science fiction/western (The Secret Empire, (inspired by 1935's The Phantom Empire) starring Geoffrey Scott as Marshal Jim Donner and Mark Lenard as Emperor Thorval) and a mystery (Stop Susan Williams!, starring Susan Anton, Ray Walston as Bob Richards, and Albert Paulsen as the villain Anthony Korf). Though final episodes were shot, the series was canceled and the last program aired on May 1, 1979 before all of the serials could conclude; only The Curse of Dracula was resolved.

In 2006, Dark Horse Indie films, through Image Entertainment, released a 6-chapter serial parody called Monarch of the Moon, detailing the adventures of a hero named the Yellow Jacket, who could control Yellow Jackets with his voice, battled "Japbots", and traveled to the moon. The end credits promised a second serial, Commie Commandos From Mars. Dark Horse attempted to promote the release as a just-found, never-before-released serial made in 1946, but suppressed by the US Government.

Public domain

[edit]Several serials are now in the public domain. These can often be downloaded legally over the internet or purchased as budget-priced DVDs. The list of public domain serials includes:

- The Vanishing Legion with Harry Carey (1931)

- The Hurricane Express with John Wayne (1933)

- Burn 'Em Up Barnes with Frankie Darro (1934)

- The Lost City with Kane Richmond (1935)

- The New Adventures of Tarzan with Herman Brix (1935)

- The Phantom Empire with Gene Autry (1935)

- Undersea Kingdom with Ray Corrigan (1936)

- Ace Drummond with John 'Dusty' King (1936)

- Dick Tracy with Ralph Byrd (1937)

- Zorro's Fighting Legion with Reed Hadley (1939)

- The Phantom Creeps with Bela Lugosi (1939)

- Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe with Buster Crabbe (1940)

- The Green Archer with Victor Jory (1940)

- Holt of the Secret Service with Jack Holt (1941)

- Gang Busters with Kent Taylor (1942)

- Captain America with Dick Purcell (1944)

- The Great Alaskan Mystery with Milburn Stone (1944)

- Zorro's Black Whip with Linda Stirling (1944)

- Radar Men from the Moon with Roy Barcroft (1952, originally conceived as a TV series)

Selected film serials

[edit]Selected serials of the Silent Era

[edit]- What Happened to Mary? (1912)

- The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913)

- Fantômas (1913) – (Cinema of France)

- The Perils of Pauline (1914)

- The Hazards of Helen (1917)

- The Exploits of Elaine (1914)

- Les Vampires (1915) – (Cinema of France)

- The Ventures of Marguerite (1915)

- Les Mystères de New York (1916)

- Le Masque aux Dents Blanches (1917)

- Judex (1917)

- Casey of the Coast Guard (1926)

- Tarzan the Mighty (1928)[14]

- Queen of the Northwoods (1929) (Last serial from Pathé)

- Tarzan the Tiger (1929) (partial sound)

Serials of the golden age of serials

[edit]The "golden age" of serials is generally from 1936 to 1945.[15] Postwar expenses limited large-scale production, so the serial form continued on a smaller scale for another decade.

- Ace Drummond (Universal, 1936)

- Custer's Last Stand (Weiss Bros., 1936)

- Darkest Africa (Republic, 1936)

- Flash Gordon (Universal, 1936)

- Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island (Republic, 1936)

- Shadow of Chinatown (Victory, 1936)

- The Adventures of Frank Merriwell (Universal, 1936)

- The Clutching Hand (Weiss Bros., 1936)

- The Black Coin (Weiss Bros., 1936)

- The Phantom Rider (Universal, 1936)

- The Vigilantes Are Coming (Republic, 1936)

- Undersea Kingdom (Republic, 1936)

- Blake of Scotland Yard (Victory, 1937)

- Dick Tracy (Republic, 1937)

- Jungle Jim (Universal, 1937)

- Jungle Menace (Weiss Bros./Columbia, 1937)

- Radio Patrol (Universal, 1937)

- S.O.S. Coast Guard (Victory. 1937)

- Secret Agent X-9 (Universal, 1937)

- The Mysterious Pilot (Weiss Bros./Columbia, 1937)

- The Painted Stallion (Republic, 1937)

- Tim Tyler's Luck (Universal, 1937)

- Wild West Days (Universal, 1937)

- Zorro Rides Again (Republic, 1937)

- Dick Tracy Returns (Republic, 1938)

- Flaming Frontiers (Universal, 1938)

- Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars (Universal, 1938)

- Hawk of the Wilderness (Republic, 1938)

- Red Barry (Universal, 1938)

- The Fighting Devil Dogs (Republic, 1938)

- The Secret of Treasure Island (Weiss Bros./Columbia, 1938)

- The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok (Columbia, 1938)

- The Lone Ranger (Republic, 1938)

- The Spider's Web (Columbia, 1938)

- Buck Rogers (Universal, 1939)

- Daredevils of the Red Circle (Republic, 1939)

- Dick Tracy's G-Men (Republic, 1939)

- Flying G-Men (Columbia, 1939)

- Mandrake the Magician (Columbia, 1939)

- Overland with Kit Carson (Columbia, 1939)

- Scouts to the Rescue (Universal, 1939)

- The Lone Ranger Rides Again (Republic, 1939)

- The Oregon Trail (Universal, 1939)

- The Phantom Creeps (Universal, 1939)

- Zorro's Fighting Legion (Republic, 1939)

- Adventures of Red Ryder (Republic, 1940)

- Deadwood Dick (Columbia, 1940)

- Drums of Fu Manchu (Republic, 1940)

- Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (Universal, 1940)

- Junior G-Men (Universal, 1940)

- King of the Royal Mounted (Republic, 1940)

- Mysterious Doctor Satan (Republic, 1940)

- Terry and the Pirates (Columbia, 1940)

- The Green Archer (Columbia, 1940)

- The Green Hornet (Universal, 1940)

- The Green Hornet Strikes Again (Universal, 1940)

- The Shadow (Columbia, 1940)

- Winners of the West (Universal, 1940)

- Adventures of Captain Marvel (Republic, 1941)

- Dick Tracy vs. Crime, Inc. (Republic, 1941)

- Holt of the Secret Service (Columbia, 1941)

- Jungle Girl (Republic, 1941)

- King of the Texas Rangers (Republic, 1941)

- Riders of Death Valley (Universal, 1941)

- Sea Raiders (Universal, 1941)

- Sky Raiders (Universal, 1941)

- The Iron Claw (Columbia, 1941)

- The Spider Returns (Columbia, 1941)

- White Eagle (Columbia, 1941)

- Captain Midnight (Columbia, 1942)

- Don Winslow of the Navy (Universal, 1942)

- Gang Busters (Universal, 1942)

- Junior G-Men of the Air (Universal, 1942)

- King of the Mounties (Republic, 1942)

- Overland Mail (Universal, 1942)

- Perils of Nyoka (Republic, 1942)

- Perils of the Royal Mounted (Columbia, 1942)

- Spy Smasher (Republic, 1942)

- The Secret Code (Columbia, 1942)

- The Valley of Vanishing Men (Columbia, 1942)

- Adventures of the Flying Cadets (Universal, 1943)

- Batman (Columbia, 1943)

- Daredevils of the West (Republic, 1943)

- Don Winslow of the Coast Guard (Universal, 1943)

- G-Men vs. the Black Dragon (Republic, 1943)

- Secret Service in Darkest Africa (Republic, 1943)

- The Adventures of Smilin' Jack (Universal, 1943)

- The Masked Marvel (Republic, 1943)

- The Phantom (Columbia, 1943)

- Black Arrow (Columbia, 1944)

- Captain America (Republic, 1944)

- Haunted Harbor (Republic, 1944)

- Raiders of Ghost City (Universal, 1944)

- The Desert Hawk (Columbia, 1944)

- The Great Alaskan Mystery (Universal, 1944)

- Mystery of the River Boat (Universal, 1944)

- The Tiger Woman (Republic, 1944)

- Zorro's Black Whip (Republic, 1944)

- Brenda Starr, Reporter (Columbia, 1945)

- Federal Operator 99 (Republic, 1945)

- Jungle Queen (Universal, 1945)

- Jungle Raiders (Columbia, 1945)

- Manhunt of Mystery Island (Republic, 1945)

- Secret Agent X-9 (Universal, 1945)

- The Master Key (Universal, 1945)

- The Monster and the Ape (Columbia, 1945)

- The Purple Monster Strikes (Republic, 1945)

- The Royal Mounted Rides Again (Universal, 1945)

Other notable serials

[edit]- The King of the Kongo (1929) – First serial with sound (a Mascot production)

- The Mysterious Mr. M (1946) – Last serial from Universal

- Superman (1948) - First live-action appearance of Superman on film

- King of the Carnival (1955) – Last serial from Republic

- Blazing the Overland Trail (1956) – Last American serial (a Columbia production)

- Super Giant (1957) – Japanese tokusatsu superhero film serial (a Shintoho production), released in the U.S. as Starman

See also

[edit]- List of film serials by year

- List of film serials by studio

- Pulp magazines, a contemporary, and similar, form of serialized fiction.

- The Star Wars and Indiana Jones film series; creator George Lucas says that both series were based on and influenced by serial films.

- List of fictional shared universes in film and television

- Marvel Cinematic Universe

- Serial (radio and television)

References

[edit]- ^ "Progressive Silent Film List: Arsene Lupin Contra Sherlock Holmes". Silent Era. September 28, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "Progressive Silent Film List: Raffles". Silent Era. October 12, 2004. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Hollywood Reporter, "Columbia Drops Weiss Options for Serial Pix", Apr. 6, 1938.

- ^ Scott MacGillivray and Jan MacGillivray, Gloria Jean: A Little Bit of Heaven, iUniverse, 2005, p. 203.

- ^ Allison, Deborah (Winter 2023). "To cut a long story short: the featurization of American sound serials". Screen. 64 (4): 401–425. doi:10.1093/screen/hjad035.

- ^ Film Daily, Jan. 2, 1940, p. 2.

- ^ Broadcasting, April 15, 1963, pp. 74-75.

- ^ Motion Picture Herald, July 14, 1956, p. 17.

- ^ Motion Picture Daily, Dec. 7, 1956, p. 1.

- ^ Variety, July 10, 1957, p. 33.

- ^ "Search Results – BBC Genome". BBC. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- ^ "Blackie Seymour,, 72". Telegram & Gazette. May 4, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ "Wildcat" Movie Serial Official Site

- ^ "Progressive Silent Film List: Tarzan the Mighty". silentera.com. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Images – Golden Age of the Serial. Retrieved July 10, 2007

Further reading

[edit]- Robert K. Klepper, Silent Films, 1877–1996, A Critical Guide to 646 Movies, McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-2164-9

- Lahue, Kalton C. Bound and Gagged: The Story of the Silent Serials. New York: Castle Books 1968.

- Lahue, Kalton C. Continued Next Week : A History of the Moving Picture Serial. Norman. University of Oklahoma Press. 1969

External links

[edit]- Serial Squadron

- Silent Era, Index of Silent Era Serials

- In The Balcony

- Dieselpunk Industries

- Mickey Mouse Club serials

- TV Cream

Serial film

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Elements

Serial films, also known as chapter plays, consist of a series of short films released sequentially, typically comprising 12 to 15 episodes, with each chapter running 15 to 30 minutes in length.[3] This format allowed for the gradual unfolding of a larger story, distinguishing serials from standalone features or one-off shorts by their interconnected structure.[4] Central to serial films is their episodic narrative, which builds a continuous storyline across installments, often centered on high-stakes action and adventure. Each episode concludes with a cliffhanger—a moment of intense suspense, such as a hero in imminent danger—that compels audiences to return to theaters for the resolution in the following chapter. This mechanic not only heightened dramatic tension but also served as a commercial strategy to boost repeat viewership, often supported by promotional tie-ins with magazines and newspapers. Serials predominantly featured genres like Westerns, science fiction, and mysteries, emphasizing thrilling escapades over complex character studies.[3][1] As a product of early 20th-century cinema, serial films drew directly from the tradition of 19th-century literary serials published in magazines, which used installment suspense to foster ongoing readership and revenue. The first notable example, What Happened to Mary? (1912), adapted a magazine story into 12 film chapters, establishing the medium's potential for serialized storytelling.[5] Typical plots in serial films revolved around intrepid heroes or heroines confronting villainous antagonists amid escalating perils, such as daring chases, explosive confrontations, and life-threatening traps. In classics like The Perils of Pauline (1914), the protagonist navigates a gauntlet of contrived dangers plotted by a scheming guardian, exemplifying the genre's reliance on repetitive yet escalating threats to sustain engagement.[3]Format and Distribution

Serial films were typically structured into 12 to 15 chapters, with each episode running 15 to 20 minutes, resulting in a cumulative runtime comparable to a single feature-length film but delivered incrementally over several weeks.[6] In the silent era, chapter counts often extended up to 20 or more, with episodes formatted as two-reel units approximately 20 to 30 minutes long to accommodate early projection standards and narrative pacing. By the sound era, production standardized around 12 to 15 shorter chapters to align with evolving theater programming and audience attention spans, emphasizing tighter action sequences within the reduced per-episode length.[6] Distribution relied on a episodic release model, with chapters screened weekly or bi-weekly in theaters as supporting attractions alongside main features and shorts, ensuring consistent audience draw without standalone billing. Exhibitors often integrated serial chapters into affordable matinee programs targeted at youth and working-class viewers, charging standard admission fees per screening to encourage habitual attendance across the serial's run. This staggered rollout maximized theater occupancy in independent and neighborhood venues, where serials filled slots between B-movies and cartoons, adapting to local schedules with occasional delays in rural areas. Cliffhangers at episode ends drove repeat viewership and boosted box-office returns via sustained ticket sales, with tie-ins like newspaper promotions further amplifying revenue without substantial additional investment. This model proved particularly viable for mid-tier studios, balancing modest budgets against high attendance yields from serialized retention strategies.Historical Development

Silent Era Origins

The origins of the serial film genre in the United States trace back to 1912, when Edison Studios released What Happened to Mary?, widely recognized as the first American film serial. This 12-episode production, starring Mary Fuller, adapted a magazine story and was distributed monthly as one-reel installments, each concluding with a cliffhanger to encourage repeat viewings.[7][8] A pivotal early success came in 1914 with Pathé's The Perils of Pauline, a 20-chapter serial featuring Pearl White as the adventurous heiress Pauline Marvin, who faced weekly perils ranging from train wrecks to wild animals. This production popularized the "damsel-in-distress" trope, where the heroine encountered danger but often demonstrated resourcefulness, propelling White to stardom and achieving significant commercial success.[9] European serials, particularly Louis Feuillade's French Fantômas series (1913–1914) produced by Gaumont, exerted influence on American filmmakers by introducing sophisticated crime thrillers with masked villains and intricate plots, inspiring adaptations and tropes like the elusive criminal mastermind in U.S. productions.[10] The rapid growth of serials in the 1910s was fueled by the nickelodeon theater boom, where affordable five-cent admissions in storefront venues demanded frequent, low-cost content changes—often twice weekly—prompting studios to develop serialized narratives that built loyal audiences through suspenseful continuations. These formats helped establish cinema as a mass entertainment medium during the industry's formative years, with serials comprising a significant portion of the short-film programs that attracted working-class and immigrant viewers.[11][12] Early serials faced technical challenges inherent to the silent era, including rudimentary special effects reliant on simple mattes, miniatures, and practical stunts rather than advanced optical processes, which limited spectacle in action sequences. Additionally, the black-and-white format, standard due to the high cost and unavailability of color film stock, constrained visual storytelling by reducing depth and emotional nuance, though tinting techniques were sometimes applied post-production for mood enhancement.[13][14]Golden Age Expansion

During the 1920s and early 1930s, serial films reached a peak of popularity in the late silent era and during the initial transition to sound, with dozens produced annually as studios capitalized on the format's appeal for repeat theater attendance. Between 1920 and 1930, over 70 silent serials were released, led by major producers Universal and Pathé, which together accounted for a substantial portion of output; for instance, in 1925 alone, Pathé released five serials and Universal four, alongside four from smaller companies.[15][16][17] Serials diversified beyond early adventure tales, incorporating genres such as science fiction and Westerns while evolving the suspense-driven styles pioneered in works like The Exploits of Elaine (1914–1915). Examples include sci-fi entries like The Invisible Ray (1920), which featured experimental ray technology in a mystery plot, and adventure adaptations drawing from popular literature, such as elements in The Lost World (1925), though primarily a feature, it influenced serial-like episodic storytelling in fantasy realms. Western serials also gained traction, with action-oriented narratives emphasizing heroism and chases across rugged landscapes.[18][19] A star system emerged, with performers building franchises through recurring roles that drew audiences back weekly; actors like Ruth Roland exemplified this in adventure serials such as The Eagle's Talons (1923), leveraging their charisma and stunt skills to create enduring personas in the format.[20][21] Market expansion propelled serials internationally, particularly to Europe and Asia, where they contributed to cinema's globalization by filling programming slots in emerging theaters and appealing to diverse audiences with universal adventure themes. American serials were widely distributed abroad, aiding Hollywood's dominance of global screens by the mid-1920s, with exports to markets like China showcasing their role in cultural exchange.[22][23] Economically, serials represented a significant portion of studio output—estimated at 20-30% for key producers—fueled by the needs of theater chains for affordable, episodic content to boost attendance and revenue during the booming cinema era. This reliance on serials helped studios like Universal sustain production amid rising competition, as the format's low-cost, high-engagement model aligned with the era's expanding exhibition networks.[16][24]Sound Era Transition and Decline

The transition to synchronized sound in film serials occurred in the late 1920s, aligning with Hollywood's broader adoption of sound technology beginning in 1927–1928. The first serial to incorporate sound elements was The King of the Kongo (1929), a Pathé production that adapted and expanded upon a 1922 silent serial of the same name by adding synchronized dialogue, music, and sound effects, though it remained a partial-talkie hybrid. This marked a pivotal shift, as sound enhanced dramatic tension and character development in the cliffhanger format while retaining the episodic structure familiar to audiences.[25] Producers faced substantial adaptation challenges with the onset of sound, primarily due to the elevated costs of acquiring and operating sound recording equipment, hiring technicians, and integrating post-production audio work. These expenses prompted a reformatting of serials to optimize profitability: instead of the 15–20 short chapters (10–15 minutes each) common in the silent era, sound serials typically featured 12–15 longer episodes running 20–30 minutes apiece, allowing for more substantial narrative arcs within reduced overall production demands.[26] Sound serials flourished during the 1930s and 1940s, achieving their zenith as affordable B-movie entertainment amid the Great Depression and wartime escapism. Republic Pictures dominated this period, producing over 60 serials renowned for their polished action sequences, elaborate stunts, and charismatic heroes; notable examples include Zorro's Black Whip (1944), which blended Western and masked-avenger tropes to captivate theatergoers with its fast-paced adventures and romantic subplots. Republic's output, often exceeding 200,000 feet of film per serial, underscored the studio's role in sustaining the genre's popularity through innovative use of sound for heightened suspense and musical cues.[27] The genre's decline accelerated after World War II, driven by the explosive growth of television, which offered serialized content directly into homes at lower cost and greater convenience, eroding theatrical attendance for short subjects. Concurrently, escalating budgets for feature films, coupled with major studio mergers and antitrust rulings that dismantled the vertical integration model, curtailed B-movie production pipelines; by the early 1950s, output dwindled as studios like Columbia and Republic prioritized television syndication over new serials. The last significant theatrical serial, King of the Congo (1952), a Columbia jungle adventure starring Buster Crabbe, symbolized the end of the format, after which remaining chapters were repurposed for TV broadcast rather than cinema release.[28]Production Practices

Studio Involvement

Pathé Exchange, the American arm of the French Pathé Frères studio, pioneered serial film production in the United States during the silent era, releasing influential chapter plays like The Perils of Pauline in 1914 that established the format's popularity among audiences.[29] Universal Pictures emerged as an early leader in the genre, beginning serial production in 1914 with titles such as Lucille Love, the Girl of Mystery and maintaining a consistent output through the 1920s and 1930s under producer Henry MacRae, whose career at the studio spanned from 1912 and earned him the nickname "King of Serial Makers" for helming dozens of entries.[17][30] Columbia Pictures also became a significant player in the sound era, producing around 57 serials from 1940 to 1956, including adaptations like Batman (1943). In the sound era, Republic Pictures dominated as the genre's preeminent producer, releasing 66 serials between 1936 and 1955, including high-profile adaptations like The Lone Ranger (1938) and Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941).[31] Key creative personnel shaped these studios' outputs, with directors and producers balancing low budgets against audience demands for action. At Republic, William Witney specialized in dynamic action sequences, directing or co-directing 23 serials between 1937 and 1946, often emphasizing elaborate stunts that became a hallmark of the studio's style.[32] Henry MacRae, Universal's head of serial production in the 1920s and 1930s, oversaw ambitious projects like The Indians Are Coming (1930), the studio's first all-talking serial, and later sound-era hits such as Flash Gordon (1936), leveraging his experience to innovate within tight constraints.[17][30] Studio strategies varied by era and scale, with many operations resembling "Poverty Row" independents that prioritized cost-cutting over prestige, producing serials on budgets as low as $100,000 per chapter play through reused sets and minimal casts.[33] In contrast, subsidiaries of major studios like Universal integrated serials into broader feature-film pipelines, though still as B-unit projects. Republic exemplified an efficient in-house model, owning its own studio facilities and laboratory to streamline production, positioning itself between Poverty Row economics and major-studio resources without relying on parent company oversight.[26] Industry dynamics included significant mergers that altered serial output, such as Pathé Exchange's acquisition by RKO Radio Pictures in January 1931 for $4.6 million, which integrated Pathé's Culver City studio but curtailed its independent serial production as resources shifted toward RKO's feature films.[34] To manage escalating costs in the 1930s and 1940s, studios heavily relied on stunt performers for high-risk action—often doubling leads in dangerous sequences—and extensive stock footage from prior productions, keeping per-episode expenses under control.[35][32]Filmmaking Techniques

Serial films employed efficient shooting practices to facilitate rapid production within tight budgets, filming episodes out of sequence to optimize the use of standing sets and locations while incorporating recycled and library footage from prior productions. This method enabled studios to generate an entire serial of 12-15 chapters in 4-6 weeks, prioritizing action-heavy scenes to captivate audiences with minimal downtime between shoots.[36][37] Special effects in serials relied on practical stunts and in-camera techniques rather than later digital methods, with matte paintings and miniatures creating fantastical environments and destruction sequences affordably. Republic Pictures exemplified this approach through the work of effects specialists Howard and Theodore Lydecker, who constructed detailed miniatures for dynamic action in serials like Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), building on earlier innovations seen in Universal's Flash Gordon (1936). Budgets for 1930s serials typically ranged from $100,000 to $200,000, with roughly 70% devoted to action sequences involving these effects and stunts—for instance, Republic's The Lone Ranger (1938) cost $160,315 overall. Editing techniques emphasized pace to sustain viewer engagement, particularly in fight scenes where rapid cuts created a sense of urgency through quick intercuts of punches, dodges, and falls. This fast tempo contrasted with slower narrative portions, amplifying the thrill of chases and brawls without relying on extended takes.[38] Safety innovations were crucial for the high-risk stunts that defined serials, including the development of wire work—precursors to modern wire-fu—for simulating flight and leaps, and crash mats to absorb impacts from falls and collisions. These methods allowed performers to execute perilous feats, such as building jumps and vehicle crashes, while reducing injury risks in an era before stringent regulations. Studio oversight ensured these techniques were standardized across productions to balance spectacle and performer welfare.[39][40]Narrative Structure

Serial films employed a distinctive episodic arc, wherein each chapter presented self-contained perils that resolved the previous installment's cliffhanger while advancing an overarching plot toward resolution in the finale.[41] This structure ensured weekly engagement, with individual episodes focusing on immediate threats like chases or traps, culminating in a multi-chapter narrative of heroism and villainy.[3] Central to this format were cliffhanger mechanics, often termed "killer endings," where protagonists faced apparent doom through falls, explosions, or captures to heighten suspense and compel return viewership.[41] Resolutions typically occurred via editing tricks in the subsequent episode, such as off-screen substitutions—e.g., a hero seemingly plummeting to death but caught by a net—or augmented footage that altered the peril's outcome without contradicting the prior scene.[41] In a study of 22 Golden Age serials (1936–1945), 51% of such take-outs used sequential continuity, 32% added new elements for reinterpretation, and 17% introduced incompatible resolutions to sustain the hero's invincibility.[41] Character archetypes reinforced the formulaic repetition essential for audience familiarity, featuring invincible heroes who thwarted threats with resourcefulness, recurring villains embodying cunning evil, and damsels in distress requiring rescue.[3] Examples include heroes like Mandrake the Magician or Nyoka the Jungle Girl, who endured mortal dangers yet prevailed, often aided by sidekicks against masked antagonists such as the Scorpion or Clutching Hand.[41] This archetypal setup, drawn from melodrama traditions, prioritized clear moral binaries and repetitive perils to maintain narrative momentum across 12–15 chapters.[3] To aid viewer recall amid weekly screenings, episodes opened with 1–2 minute recap sequences summarizing prior events through narration, text intertitles, or clipped footage of the cliffhanger.[41] Columbia serials favored voice-over recaps, while Republic and Universal used textual summaries, ensuring accessibility for intermittent audiences without disrupting the action's flow.[41] Pacing evolved from the silent era's simpler, visually driven plots emphasizing physical stunts and linear adventures to the sound era's incorporation of dialogue-enabled subplots for added narrative depth and character interplay.[3] Silent serials like those from the 1910s relied on rapid cuts and intertitles for brisk tempo, whereas 1930s sound productions layered interpersonal dynamics and verbal threats, extending episode complexity while preserving the core cliffhanger rhythm.[41] This shift aligned with broader cinematic trends, enhancing tension through synchronized audio but maintaining the format's reliance on narrative hooks for sustained distribution.[3]Stylistic Variations

Differences by Studio

Universal serials frequently incorporated atmospheric horror-adventure hybrids, leveraging elaborate sets to evoke suspense and otherworldly intrigue. A prime example is The Vanishing Shadow (1934), a 12-chapter production where the protagonist, aided by a mad scientist's invisibility device and ray guns, battles political corruption in a narrative blending mystery, invention, and shadowy threats.[42] This approach drew on Universal's expertise in horror elements, creating immersive environments that distinguished their chapterplays from more straightforward action fare.[42] Republic Pictures, succeeding Mascot, prioritized fast-paced action in its serials, excelling in elaborate stunts and dynamic music scores that amplified tension and heroism. Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), a 12-chapter adaptation of the Fawcett Comics superhero, showcased Republic's strengths through high-energy sequences, including daring leaps, explosive confrontations, and the innovative use of wirework for flight effects, setting a benchmark for kinetic storytelling.[42] Directors like William Witney and John English, key figures in Republic's unit, drove this emphasis on visceral spectacle.[42] Columbia's serials adopted a budget-conscious model, focusing on Westerns and mysteries while often reusing props and footage to maximize efficiency without sacrificing core appeal. In The Phantom (1943), a 15-chapter comic strip adaptation starring Tom Tyler as the purple-clad jungle hero, Columbia recycled sets and action clips from prior productions, resulting in a cost-effective yet engaging tale of tribal intrigue and vigilantism.[42] This pragmatic style reflected Columbia's strategy of delivering reliable entertainment on limited resources. Pathé and Mascot Pictures led early experimentation with science fiction in serials, introducing speculative elements like advanced technology and futuristic societies during the shift to sound, though production quality fluctuated amid technical challenges. Mascot's The Phantom Empire (1935), a pioneering 12-chapter hybrid of Western and sci-fi directed by Otto Brower and B. Reeves Eason, featured underground civilizations and ray weapons, marking a bold fusion of genres that influenced later entries.[42] Both Republic and Universal produced serials typically ranging from 12 to 15 chapters, allowing flexibility in narrative depth and production costs. These variations allowed each to target distinct audience expectations, from Republic's epic scope to Universal's taut efficiency.[42]Influences and Innovations

Serial films drew heavily from literary traditions, particularly the serialized narratives of dime novels and pulp magazines that popularized adventure, mystery, and heroism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These cheap publications, such as those from Beadle & Adams and Frank A. Munsey's Argosy, featured episodic stories of swashbuckling exploits and exotic quests, directly inspiring early serial adaptations. For instance, Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan novels, initially serialized in pulps like All-Story Weekly starting in 1912, led to the 1929 Universal serial Tarzan the Tiger, which adapted elements from Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar to emphasize jungle perils and moral triumphs. Similarly, Johnston McCulley's Zorro, debuting in the 1919 pulp story "The Curse of Capistrano" in All-Story Weekly, influenced serials like Republic's Zorro's Fighting Legion (1939), capturing the masked vigilante's fight against injustice in a format that mirrored the original's cliffhanger-driven installments.[43][44][45] Comic strips provided another key influence, shaping the visual and narrative aesthetics of serial films through dynamic panel compositions and recurring characters. Newspaper adventures like Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, launched in 1931, offered gritty detective tales with exaggerated villains and urban action, which translated seamlessly to the screen in Republic's four serials from 1937 to 1941, starring Ralph Byrd. These adaptations borrowed the comic's tight framing and iconic character designs, such as Tracy's fedora and the grotesque rogues, to enhance visual tension and audience familiarity. This cross-medium synergy extended the strips' episodic structure, reinforcing serial films' emphasis on moral clarity and heroic persistence against criminal odds. Creative innovations in the late 1930s elevated serial storytelling, with studios like Republic introducing chapter titles as provocative teasers to heighten anticipation, often previewing perils like "Doomed to Die" or "The Scorpion Strikes." This technique built on earlier cliffhangers but added psychological suspense, drawing viewers back weekly. By the late 1930s, multi-cliffhanger episodes emerged, featuring layered perils—such as a hero facing both a collapsing bridge and an ambush— to amplify drama and extend narrative threads across installments, as seen in Universal's Flash Gordon series (1936–1940). These advancements refined the form's pacing, making serials more immersive and commercially potent during the sound era.[43] Genre crossovers further enriched serial films, particularly through integration with radio dramas, which informed exaggerated sound design for heightened realism in action sequences. Radio serials like The Green Hornet (debuting 1936) inspired Universal's 1940 film adaptation, incorporating amplified effects for fistfights and chases to mimic the auditory intensity of broadcasts. During World War II, serial films served cultural purposes by promoting heroism and Allied values through propaganda-infused narratives, transforming everyday protagonists into symbols of national resilience. Republic's Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941) depicted Billy Batson as an everyman who becomes a superhuman defender, emphasizing moral duty against a shadowy evil that paralleled Axis threats, thereby inculturating preparedness among youth audiences. Similarly, Spy Smasher (1942) featured twin brothers fighting a Nazi-like Masked villain, using V-for-victory motifs and calls to "defend their country" to foster patriotism and sacrifice. These serials, aimed at children and families, reinforced American exceptionalism and unity, blending entertainment with wartime morale-boosting messages.[46]Availability and Legacy

Historical Exhibition Methods

Serial films were primarily exhibited in theaters via weekly chapter releases during the 1930s and 1940s, forming a key component of Saturday afternoon matinee programs designed for children. These "kiddie matinees," which ran from the 1930s through the 1960s, offered an affordable entertainment package—typically priced at 10 to 25 cents—featuring a 15- to 20-minute serial installment alongside animated cartoons, comedy shorts, newsreels, and a low-budget feature film. The cliffhanger endings at the close of each chapter, such as a hero appearing to plummet to his death, compelled young audiences to return the following week, fostering loyalty and boosting theater attendance among families. Producers like Universal, Columbia, and Republic tailored serials to this format, with examples like Flash Gordon (1936) and The Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941) becoming staples of these youth-oriented screenings.[47][48] In the 1940s and 1950s, re-releases of established serials became a common exhibition strategy for theaters facing wartime material shortages and postwar production challenges. With new film stock rationed during World War II and studio output limited, exhibitors recycled popular titles to sustain programming, often pairing reissued chapters with current shorts or B-movies to create full matinee bills. Studios including Republic and Columbia initiated widespread reissues around 1947, reducing the need for annual new serial production from four to two per studio while capitalizing on proven hits like Zorro's Black Whip (1944) or The Phantom (1943). This approach not only cut costs but also introduced serials to new generations of children amid declining original output, helping theaters maintain weekly family draws until the mid-1950s.[49][50] By the 1950s, early television syndication expanded serial exhibition beyond theaters, with local stations broadcasting edited chapters to fill afternoon slots. Columbia's subsidiary Screen Gems acquired syndication rights to many serials in 1956 through its purchase of Hygo Television Films, repackaging 12- to 15-chapter runs into half-hour episodes by condensing recaps and resolutions to suit TV pacing. Independent and network-affiliated stations aired these on weekdays or weekends, targeting after-school youth audiences and introducing cliffhanger storytelling to home viewers, as seen with broadcasts of Superman (1948) and Jungle Jim (1937). This shift democratized access but often resulted in cuts to action sequences for time constraints, marking the transition from communal theater experiences to individual living-room viewing.[51][52] Drive-in and second-run theaters sustained serial exhibition into the 1950s and 1960s, appealing to families seeking budget-friendly outings. These outdoor venues, peaking at over 4,000 in the U.S. by 1958, programmed reissued serial chapters as part of double features with cartoons and shorts, allowing parents to watch from cars while children enjoyed the adventure serials on screen. Second-run indoor houses similarly recycled content for neighborhood crowds, emphasizing family-oriented Westerns and sci-fi serials like King of the Rocket Men (1949) to compete with rising TV popularity. This format preserved the communal thrill of matinees in a post-theater era, with drive-ins offering speakers for car audio and playgrounds to entertain kids during intermissions.[53][54] Internationally, serial films faced adaptations including dubbing and censored edits, particularly in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s, to navigate language barriers and political sensitivities. In Italy under Mussolini's regime, dubbing replaced original audio with Italian tracks starting in 1930, enabling censors to excise anti-fascist dialogue or references, as in alterations to American imports like early Republic serials. Spain's Franco-era policies similarly mandated full dubbing to suppress regional languages and enforce ideological conformity, often shortening violent chapters in adventure serials for moral reasons. Germany post-1945 continued dubbing practices, revoicing serials to neutralize Nazi-era connotations while complying with Allied oversight, ensuring broader market penetration despite fragmented distribution. These modifications prioritized local acceptability over fidelity, varying by market to sustain serials' global appeal.[55][56]Modern Access Formats

The resurgence of interest in serial films from the mid-1980s onward spurred a boom in home video releases, making these chapterplays accessible beyond theaters and television reruns. Companies like GoodTimes Home Video and Rhino Home Video pioneered VHS distributions in the 1980s, often compiling episodes from surviving 16mm prints into affordable tape sets for collectors and nostalgia enthusiasts. By the 1990s and into the 2000s, the transition to DVD elevated quality, with Image Entertainment handling U.S. distribution for restored editions of Republic Pictures serials, such as the 1944 "Zorro's Black Whip" and the 1946 "The Crimson Ghost," which featured cleaned-up transfers and bonus materials like original trailers.[57] These releases, typically priced under $20, sold steadily through specialty retailers and online platforms, preserving the fast-paced action and cliffhanger elements for home audiences.[57] The streaming era, beginning in the late 2000s and accelerating through the 2010s, democratized access to serials via digital platforms, particularly for public domain titles. Universal's 1936 "Flash Gordon" serial, digitized from early DVD transfers, became widely available on YouTube around 2010, with full 13-chapter playlists garnering millions of views and enabling binge-watching of its rocket-ship adventures and ray-gun battles. Free ad-supported services like Tubi followed suit, streaming episodes of "Flash Gordon: The Peril from Planet Mongo" (1938) and other pre-1950 serials without subscription fees, often sourced from the same public domain archives. Full series remain more common on open platforms.[58][59] Advancements in home media continued into the 2020s with Blu-ray and 4K restorations, driven by boutique labels specializing in classic cinema. VCI Entertainment released 2K-restored DVDs of Universal serials like the 1940 "Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe." These editions, often limited to 1,000–2,000 units, include commentary tracks from film historians, underscoring the technical challenges of restoring nitrate-based originals.[60] Fan-driven efforts have further expanded modern access, particularly through online sharing since the 2010s. Enthusiasts on platforms like archive.org upload amateur restorations, including AI-upscaled versions of silent serials such as "The Perils of Pauline" (1914), where machine learning algorithms sharpen resolution to near-HD levels and add subtle color tints for dramatic effect. Since the early 2020s, these community projects—shared via forums and torrent sites—have included colorized public domain serials, blending historical accuracy with creative enhancements to attract younger viewers, though purists debate their authenticity.[61] While not true serials, recent streaming productions in the 2020s have revived the format's episodic spirit. Disney+'s "The Mandalorian" (2019–2023), created by Jon Favreau, emulates classic serials through self-contained "chapters" ending in cliffhangers, directly inspired by the adventure serials that influenced George Lucas, as Favreau noted in interviews. This structure, combined with bounty-hunter archetypes from 1930s chapterplays, has popularized serialized storytelling on premium platforms. The public domain status of many vintage serials has aided these digital revivals by providing free source material for study and homage.[62]Public Domain and Preservation Efforts

Most pre-1928 silent serial films have entered the public domain in the United States, with copyrights for works published before 1923 expiring by the late 1990s under pre-1998 laws, and those from 1923 to 1927 becoming freely available between 2019 and 2023 due to the 95-year term for pre-1978 publications. Sound-era serials are following suit, with 1929 releases entered the public domain on January 1, 2025, and 1930s productions—such as early Republic Pictures chapters—becoming accessible starting in 2026.[63] This progression stems from the Copyright Term Extension Act, which standardized protection durations but has systematically released early 20th-century works. Preservation of serial films is hindered by the inherent instability of nitrate film stock used in the silent era, which degrades through chemical breakdown, discoloration, and risks of auto-ignition, leading to widespread loss. Approximately 70% of all American silent films from 1912 to 1929 are considered lost, with serials particularly affected as multi-chapter formats often resulted in incomplete sets due to selective destruction or neglect after initial runs.[64] Sound serials on acetate-based film face issues like vinegar syndrome and color fading, though fewer complete losses have occurred compared to silents. Restoration efforts began in earnest in the 1970s, with the Library of Congress establishing a dedicated motion picture conservation program to copy and stabilize nitrate originals, including serial chapters from studios like Universal and Pathé. The UCLA Film & Television Archive, operational since 1977, has similarly restored key serials, such as the 1936 Flash Gordon from original nitrate elements, employing photochemical and digital techniques to reconstruct damaged prints.[65] In the 2020s, crowdsourced initiatives via Kickstarter have supported digital scanning of rare holdings, funding 4K transfers of silent serial fragments and enabling broader archival access.[66] Commercial preservation intersects with amateur endeavors, as studio-backed releases like Warner Archive's collections of 1940s-1950s serials—such as the Superman chapters—provide remastered Blu-ray editions from vault materials.[67] Fan-driven projects complement this by cataloging episode synopses, survival status, and cast details on dedicated sites, fostering community verification of holdings. The public domain status of early serials has spurred free online repositories, like the Internet Archive's Moving Image collection, which hosts digitized episodes for unrestricted viewing and downloading.[68] Conversely, copyrighted later serials pose legal hurdles, requiring permissions that delay institutional digitization and limit fan restorations.[69]Notable Examples

Silent Era Serials