Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

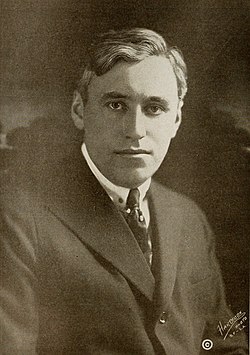

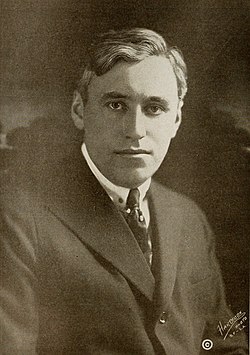

Mack Sennett

View on Wikipedia

Mack Sennett (born Michael Sinnott; January 17, 1880 – November 5, 1960) was a Canadian-American producer, director, actor, and studio head who was known as the "King of Comedy" during his career.[1]

Key Information

Born in Danville, Quebec,[2][3][4][a] he started acting in films in the Biograph Company of New York City in 1908, and later opened Keystone Studios in Edendale, California in 1912. Keystone possessed the first fully enclosed film stage, and Sennett became famous as the originator of slapstick routines such as pie-throwing and car-chases, as seen in the Keystone Cops films.[5] He also produced short features that displayed his Bathing Beauties, many of whom went on to develop successful acting careers.[6][7]

After struggling with bankruptcy and the dominance of sound films in the early 1930s, Sennett was presented with an honorary Academy Award in 1938 for his contributions to the film industry, with the academy describing him as a "master of fun, discoverer of stars, sympathetic, kindly, understanding comedy genius".[8]

Early life

[edit]Born Michael Sinnott in Danville, Quebec,[2] to parents of Irish Catholic descent, John Sinnott and Catherine Foy (or Foye). His parents married in 1879 in Tingwick, Quebec and moved the same year to Richmond, Quebec where Sinnott was hired as a laborer.[9] By 1883, when Sennett's brother George was born, Sinnott was working as an innkeeper, a position he held for many years. Sennett's parents had all their children and raised their family in Richmond, then a small Eastern Townships village. At that time, Sennett's grandparents were living in Danville, Quebec. Sennett moved to Connecticut when he was 17 years old.[9]

He lived for a while in Northampton, Massachusetts, where, according to his autobiography, he first got the idea to become an opera singer after seeing a vaudeville show. He said that the most respected lawyer in town, Northampton mayor (and future President of the United States) Calvin Coolidge, as well as Sennett's mother, tried to talk him out of his musical ambitions.[10] In New York City, he took on the stage name Mack Sennett and became an actor, singer, dancer, clown, set designer, and director for the Biograph Company. A distinction in his acting career, often overlooked, is that he played Sherlock Holmes 11 times, albeit as a parody, between 1911 and 1913.[11]

Keystone Studios

[edit]

With financial backing from Adam Kessel and Charles O. Bauman of the New York Motion Picture Company, Sennett founded Keystone Studios in Edendale, California – now a part of Echo Park – in 1912. The original main building which was the first totally enclosed film stage and studio ever constructed,[1] is still standing, as of 2023.[12] Many successful actors began their film careers with Sennett, including Marie Dressler, Mabel Normand, Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langdon, Roscoe Arbuckle, Harold Lloyd, Raymond Griffith, Gloria Swanson, Charley Chase, Ford Sterling, Andy Clyde, Chester Conklin, Polly Moran, Slim Summerville, Louise Fazenda, The Keystone Cops, Carole Lombard, Bing Crosby, and W. C. Fields.[b][c]

"In its pre-1920s heyday [Sennett's Fun Factory] created a vigorous new style of motion picture comedy founded on speed, insolence and destruction, which won them the undying affection of the French Dadaists..." —Film historian Richard Koszarski[15]

Dubbed the King of Hollywood's Fun Factory,[16] Sennett's studios produced slapstick comedies that were noted for their hair-raising car chases and custard pie warfare, especially in the Keystone Cops series. The comic formulas, however well executed, were based on humorous situations rather than the personal traits of the comedians; the various social types, often grotesquely portrayed by members of Sennett's troupe, were adequate to render the largely "interchangeable routines: "Having a funny moustache, or crossed-eyes, or an extra two-hundred pounds was as much individualization as was required."[d][17]

"It is an axiom of screen comedy that a Shetland pony must never be put in an undignified position. People don't like it...immunity of pretty girls doesn't go as far as the immunity of the Shetland pony...you can have her fall into mud puddles. They will laugh at that. But the spectacle of a girl dripping with pie is unpleasing...movie fans don't like to see pretty girls smeared up with pastry. Shetland ponies and pretty girls are immune."— Mack Sennett, from The Psychology of Film Comedy, November 1918[17]

Film historian Richard Koszarski qualifies "fun factory" influence on comedic film acting:

"While Mack Sennett has a secure and valued place in the history of screen comedy, it is surely not as a developer of individual talents ... Chaplin, Langdon, and Lloyd were all on the lot at one point or another, but developed their styles only in spite of Sennett, and grew to their artistic peaks only away from his influence ... screen comedy followed Chaplin's lead and began to focus more on personality than situation."[e]

Sennett's first female comedian was Mabel Normand, who became a major star under his direction and with whom he embarked on a tumultuous romantic relationship.[10] Sennett also developed the Kid Comedies, a forerunner of the Our Gang films, and in a short time, his name became synonymous with screen comedy which were called "flickers" at the time.[10] In 1915, Keystone Studios became an autonomous production unit of the ambitious Triangle Film Corporation, as Sennett joined forces with D. W. Griffith and Thomas Ince, both powerful figures in the film industry.[18]

Sennett Bathing Beauties

[edit]

Also beginning in 1915, Sennett assembled a bevy of women known as the Sennett Bathing Beauties to appear in provocative bathing costumes in comedy short subjects, in promotional material, and in promotional events such as Venice Beach beauty contests.[6] The Sennett Bathing Beauties continued to appear through 1928.[7]

Independent production

[edit]

In 1917, Sennett gave up the Keystone trademark and organized his own company, Mack Sennett Comedies Corporation.[10] Sennett's bosses retained the Keystone trademark and produced a cheap series of comedy shorts that proved unsuccessful. Sennett went on to produce more ambitious comedy short films and a few feature-length films.[10]

Many of Sennett's films of the early 1920s were inherited by Warner Bros.[11] after Warner had merged with the original distributor, First National. Warner added music and commentary to several of these short subjects, and the new versions were released to theaters between 1939 and 1945. Many of Sennett's First National films physically deteriorated due to inadequate storage. Hence, many of Sennett's films from his most productive and creative period no longer exist.[11]

Move to Pathé Exchange

[edit]In the mid-1920s, Sennett moved to Pathé Exchange distribution.[10] In 1927, Hollywood's two most successful studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Paramount Pictures, took note of the profits being made by smaller companies such as Pathé Exchange and Earle Hammons's Educational Pictures.[10] MGM took over the Hal Roach comedy shorts from Pathé, and Paramount reactivated its short subjects. Hundreds of other independent exhibitors and moviehouses switched from Pathé to the new MGM or Paramount shorts. Sennett fulfilled his contract to deliver silent comedies to Pathé through 1929 (these, like the Smith Family comedies, had already been completed before Sennett temporarily shut down his studio), but he began making sound films for Educational in late 1928.

Sound films

[edit]In 1928, Sennett canceled all of his talent contracts and retooled his studio for the new talking-picture technology. His leading star at the time, Ben Turpin, was suddenly unemployed and moved to the Weiss Brothers studio.

Sennett's enthusiasm for sound on film was such that he was the first to get a talking two-reel comedy on the market.[10] The Lion's Roar, starring Johnny Burke and Billy Bevan, was released by Educational in December 1928, launching a four-year succession of Mack Sennett sound comedies. Sennett occasionally experimented with color as well.[10]

In 1932, he was nominated for the Academy Award for Live Action Short Film in the comedy division for producing The Loud Mouth (with Matt McHugh, in the sports-heckler role later taken in Columbia Pictures remakes by Charley Chase and Shemp Howard).[19] Sennett also won an Academy Award in the novelty division for his film Wrestling Swordfish, also in 1932.[20] He directed at least two two-reel comedies under the pseudonym Michael Emmes (the "Emmes" representing Sennett's initials): Hawkins and Watkins Inc. and Young Onions (both 1932).

Mack Sennett often clung to outmoded techniques, making his early-1930s films seem dated and quaint: he dressed some of his actors in eccentric makeups and loud costumes, which were amusing in the cartoonish silent films but ludicrous in the new, realistic atmosphere of talking pictures. Sennett was also having financial problems during the Great Depression. One of his biggest stars, Andy Clyde, left the studio after Sennett, wanting to economize, tried to cut Clyde's salary.

In 1932, Sennett attempted to re-enter the feature-film market on a grand scale with Hypnotized. Remembering the successful campaign for his very first feature-length comedy Tillie's Punctured Romance, which in 1914 was the longest comedy film ever produced, Sennett planned Hypnotized along similar lines as an epic production that would be shown first-run in select roadshow engagements. Sennett announced that Hypnotized would run 15 reels, or two-and-a-half hours, more than twice the length of a typical comedy feature of the day.[21] Sennett wanted W. C. Fields to star as a carnival hypnotist, but Fields declined and the role went to Ernest Torrence, sharing the spotlight with blackface comedians Moran and Mack, "The Two Black Crows". Production was completed in August 1932, but fell far short of Sennett's grandiose predictions. The finished film ran an ordinary 70 minutes and was released through ordinary channels by World Wide Pictures (Educational's feature-film outlet) in December 1932.

Sennett was also having differences with his distributor, Earle Hammons of Educational. Jack White, Educational's leading producer, explained, "We put Mack Sennett out of business. Theaters had [our] comedies booked solid. Sennett was very temperamental and wanted the exhibitor to do certain things, but they wouldn't stand for it. Sennett wouldn't stand for Hammons not telling him how much [money] he was cutting out of the grosses for himself. Sennett told him to go to hell."[22][23] Sennett left Educational and signed with Paramount Pictures.[24]

Sennett's sound comedies usually starred young featured players like Frank Albertson or established stage comics like Walter Catlett, but Sennett didn't establish any new star names until he signed both Bing Crosby and W. C. Fields for two-reel comedies. Crosby starred in six; Fields wrote and starred in four. Two other Sennett shorts were made with Fields scripts: The Singing Boxer (1933) with Donald Novis and Too Many Highballs (1933) with Lloyd Hamilton.[10] Despite Paramount's wide distribution of the Crosby and Fields shorts, Sennett's studio did not survive the Depression.[10] Sennett's partnership with Paramount lasted only one year and he was forced into bankruptcy in November 1933.[10] His former protege Bing Crosby, whose popularity and income had skyrocketed, helped Sennett during a period of financial hardship.[25] This act prompted columnist Lloyd Pantages to refer to Crosby as Sennett's "guardian angel."[26]

On January 12, 1934, Sennett was injured in an automobile accident that killed blackface performer Charles Mack (of Moran and Mack) in Mesa, Arizona.[27]

His last work, in 1935, was as a producer-director for Educational, in which he directed Buster Keaton in The Timid Young Man and Joan Davis in Way Up Thar.[10] Sennett was not connected with the 1935 Vitaphone short subject Keystone Hotel, which featured several alumni from the Sennett studios, including Ben Turpin, Ford Sterling, Hank Mann, and Chester Conklin. The film was directed by Ralph Staub.

Sennett made one last attempt to continue working in the comedy field. By this time he had been supplanted as the major producer of two-reel comedies by Jules White at Columbia Pictures. White's brother, Jack White, recalled: "When Jules and I were at Columbia in the 1930s, Sennett tried to come to Columbia but they wouldn't have him. He was finished, and the studio was happy with Jules."[22][23] Sennett did sell some scripts and stories to Jules White, receiving screen credit under his "Michael Emmes" alias. Columbia really didn't need Sennett's services; the studio already had four producers and six directors on its short-subject payroll.[28]

Mack Sennett went into semi-retirement at the age of 55, having produced more than 1,000 silent films and several dozen talkies during a 25-year career.[10] His studio property was purchased by Mascot Pictures (later part of Republic Pictures), and many of his former staffers found work at Columbia.[10]

In March 1938, Sennett was presented with an honorary Academy Award: "for his lasting contribution to the comedy technique of the screen, the basic principles of which are as important today as when they were first put into practice, the Academy presents a Special Award to that master of fun, discoverer of stars, sympathetic, kindly, understanding comedy genius – Mack Sennett."[8][29]

Later projects

[edit]Rumors abounded that Sennett would be returning to film production (a September 1938 publicity release indicated that he would be working with Stan Laurel of Laurel and Hardy), but apart from Sennett reissuing a couple of his Bing Crosby two-reelers to theaters, nothing happened.[30]

Sennett did appear in front of the camera, however, in Hollywood Cavalcade (1939), itself a thinly disguised version of the Mack Sennett-Mabel Normand romance.[10]

In 1949, he provided film footage for the first full-length comedy compilation film, Down Memory Lane (1949), written and narrated by Steve Allen.[31][32] Sennett made a guest appearance in the film, and received a special "Mack Sennett presents" credit.

Sennett wrote a memoir, King of Comedy, in collaboration with Cameron Shipp. The book was published in 1954, prompting TV producer Ralph Edwards to mount a tribute to Sennett for the television series This Is Your Life.[33] Sennett made a cameo appearance (for $1,000) in Abbott and Costello Meet the Keystone Kops (1955).[34]

Sennett's last appearance in the national media was in the NBC radio program Biography in Sound, relating memories of working with W.C. Fields. The program was broadcast February 28, 1956.[35]

Personal life

[edit]Sennett was never married, but his tumultuous relationship with actress Mabel Normand was widely publicized in the press at the time.[36] According to the Los Angeles Times, Sennett reportedly lived a "madcap, extravagant life", often throwing "lavish parties", and at the peak of his career he owned three homes.[36]

On March 25, 1932, he became a United States citizen.[37]

Death

[edit]Sennett died on November 5, 1960, in Woodland Hills, California, aged 80.[38] He was interred in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California.[39]

Filmography

[edit]Tributes

[edit]For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Sennett was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6712 Hollywood Boulevard.[36] He was also inducted into Canada's Walk of Fame in 2014.[40]

The building of Sennett's original studio in Echo Park was deemed a historical landmark by The City of Los Angeles in 1982.[12][41]

In popular culture

[edit]- In A Story of Water, a 1961 short film by Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, the directors dedicated the film to Mack Sennett.

- In 1974, Michael Stewart and Jerry Herman wrote the musical Mack & Mabel, chronicling the romance between Sennett and Mabel Normand. Sennett was portrayed by Robert Preston in the original Broadway production, with Bernadette Peters as Normand.

- Sennett was a leading character in The Biograph Girl, a 1980 musical about the silent film era. Guy Siner appeared as Sennett in the West End production.

- Peter Lovesey's 1983 novel Keystone is a whodunnit set in the Keystone Studios and involving (among others), Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand, Roscoe Arbuckle, and the Keystone Cops.

- Dan Aykroyd portrayed Mack Sennett in the 1992 movie Chaplin alongside Marisa Tomei as Mabel Normand and Robert Downey Jr. as Charlie Chaplin.

- Joseph Beattie and Andrea Deck portrayed Mack Sennett and Mabel Normand, respectively, in episode eight of series two of ITV's Mr. Selfridge.

- Carol Burnett did a lengthy tribute skit to Mack Sennett on her show that aired on Me TV in June 2021.

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Annotations

[edit]- ^ Some sources cite Melbourne, now part of Richmond.

- ^ "Sennett trained a coterie of clowns and comediennes that made the Keystone trademark world famous: Mabel Normand, Marie Dressler, Gloria Swanson, Fatty Arbuckle, Harry Langdon, Ben Turpin, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and W.C. Fields among them. Such important directors as Frank Capra, Malcolm St. Clair, and George Stevens also received experience under Sennett's tutelage.[13]

- ^ "His gift was in providing a haven or school for ambitious young talents."[14]

- ^ "Fatty's persona as the 'jolly fat man' constrained him from being something more than that. The more conventionally good-looking Chaplin and Keaton could eventually aspire to roles that were more promising, leading to their ultimate transcendence of slapstick." And: "I have felt that Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton rose to the heights of screen comedy by distancing themselves from their Sennett/Normand/Arbuckle roots."[14]

- ^ "Sennett is [incorrectly] credited with developing most of the great comic talent of the silent film."[17]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Guy, Sep. 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "L'homme ...", Nov. 11, 2015.

- ^ Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ^ BFI.

- ^ Los Angeles Times, Sep. 29, 2014.

- ^ a b D'Haeyere, 2010, pp. 207–225.

- ^ a b Basinger, 2000, p. 205.

- ^ a b Oscars: "Special Award" 1938.

- ^ a b "Give Citizenship ...", Mar. 25, 1932, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Sennett (Shipp), 1954.

- ^ a b c Walker, Sep. 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Lank, Jan. 27, 2023.

- ^ Sinnott, 1999.

- ^ a b Silver, 2009.

- ^ Koszarski, 1976.

- ^ Walker, 2010 p. 7

- ^ a b c Koszarski, 1976, p. 54.

- ^ Booker, 2011.

- ^ Oscars database: Loud Mouth 1932.

- ^ Oscars database: Wrestling Swordfish 1931.

- ^ Film Daily, Vol. 58, no. 39, Feb. 16 1932, p. 2.

- ^ a b Bruskin, 1990, p. 103.

- ^ a b Bruskin, 1993, p. 148.

- ^ New York Times (Hoberman), Sep. 14, 2014, p. AR-14.

- ^ Giddins, 2001, p. 456.

- ^ Pantages, San Francisco Examiner, Aug. 10, 1934, p. 14.

- ^ New York Times, Jan. 12, 1934, p. 25.

- ^ Okuda & Watz, 1986, p. 20.

- ^ King, Feb. 27, 2018.

- ^ Walker, 2010, p. 227.

- ^ MacGillivray, 1998, p. 161.

- ^ MacGillivray, 2009, p. 257.

- ^ Thomas, Panama City News, Mar. 12, 1954, p. 11.

- ^ Furmanek & Palumbo, 1991, p. 245.

- ^ Biography in Sound. "Magnificent Rogue".

- ^ a b c Los Angeles Times, Nov. 6, 1960, pp. 1A & 2B.

- ^ New York Times, Mar. 26, 1932, p. 17.

- ^ New York Times, Nov. 6, 1960, pp. 1, 88.

- ^ New York Times, Nov. 24, 1960, p. 29.

- ^ Canada's Walk of Fame, 2004.

- ^ HPLA Report 2014.

References

[edit]- Basinger, Jeanine. Silent Stars. p. 205. OCLC 45474610 (all editions).

- 1999 ed (1st ed.). Alfred A. Knopf. LCCN 98-48060; ISBN 978-0-6794-3840-3, 0-6794-3840-8 (hardback), ISBN 978-0-7567-6698-6, 0-7567-6698-2, ISBN 978-0-3078-2918-4, 0-3078-2918-9 (eBook), ISBN 978-1-2992-5523-4, 1-2992-5523-X (2012 eBook).

- "Via Internet Archive" (limited preview).

- Via Google Books (limited preview).

- Via Brooklyn Public Library (2012 eBook).

- 2000 ed. Wesleyan University Press published by University Press of New England. LCCN 00-103152; ISBN 978-0-8195-6451-1, 0-8195-6451-6 (paperback)

- "Via Internet Archive" (limited preview).

- Via Google Books (limited preview).

- BFI. Mack Sennett. Archived from the original on November 30, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- Biography in Sound. Documentary series broadcast from 1954 to 1958 on NBC, created by producer Joseph Meyers.

- Magnificent Rogue: The Adventures of W.C. Fields. Aired February 28, 1956. Narrated by: Fred Allen just before his death March 17, 1956; with Edgar Bergan, Errol Flynn (1909–1959), Ed Wynn (1886–1966), and Mack Sennett }} OCLC 28559342 (all editions)

- Audio via Internet Archive. Retrieved October 30, 2025.

- Audio via Internet Archive. Retrieved October 30, 2025.

- Archive Record (Catalog No. R89:0171). New York: Paley Center for Media. Archived from the original on April 2, 2025. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- Booker, Keith M. (March 17, 2011). Historical Dictionary of American Cinema. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7459-6.

- Bruskin, David N. (1990). The White Brothers: Jack, Jules and Sam White. Metuchen, New Jersey: Directors Guild of America, Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-2314-3. LCCN 90030123. OCLC 20996738..

- Via Google Books (snippet view only). p. 103.

- Bruskin, David N. (1990). Reissued in 1993 as: Behind the Three Stooges: The White Brothers – Conversations With David N. Bruskin. Directors Guild of America. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-8827-6600-0, 1-8827-6600-8 (paperback); OCLC 29914678 (all editions).

- Canada's Walk of Fame. Mack Sennett (inducted 2004). Toronto: Toronto Entertainment District. Archived from the original on November 5, 2025. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- Canadian Encyclopedia (The). LCCN 84-243080 (1st ed.; 1984; 3 Vols.).

- English print ed (in English). Vol. 1 (of 4): "A – Edu" (2nd ed.). Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers. 1988. p. 340 – via Internet Archive (Kahle/Austin Foundation; Surrey Public Library). LCCN 89-157192; ISBN 978-0-8883-0326-4, 0-8883-0326-2 (set)

- Beard, William. Canadian Expatriates in Show Business – Sennett, Mack. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8883-0327-1, 0-8883-0327-0.

- English print ed (in English) (2000 ed.). Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. 2000. pp. 511–512 – via Internet Archive (Kahle/Austin Foundation; Surrey Public Library). LCCN 00-302429 (2000 ed.); ISBN 978-0-7710-2099-5, 0-7710-2099-6.

- Beard, William. "Canadian Expatriates in Show Business" – "Sennett, Mack". p. 372.

- Rosen, David. "Comedy" – "Mack Sennett". pp. 511–512.

- French print ed. L'Encyclopédie canadienne. Montréal, Paris, New York: Les Éditions internationales Alain Stanké. 2000. ISBN 978-2-7604-0766-4, 2-7604-0766-7.

- Rosen, David. Comédie – Sennett, Mack (in Canadian French). p. 554.

- Beard, William. Expatriés Canadiens de l'Industrie du Spectacle – Sennett, Mack (in Canadian French). p. 924.

- French blog ed. L'Encyclopédie canadienne. 2000..

- Beard, William (June 7, 2011) [updated December 16, 2013]. Blog ed.: "Mack Sennett" (in Canadian French). Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- D'haeyere, Hilde (2010). "Splashes of Fun and Beauty: Mack Sennett's Bathing Beauties". In King, Rob; Paulus, Tom (eds.). Slapstick Comedy. Routledge USA. pp. 207–225. LCCN 2011-378471; ISBN 978-0-4158-0179-9, 0-4158-0179-6, ISBN 978-0-4158-0178-2, 0-4158-0178-8, ISBN 978-0-2038-7676-3, 0-2038-7676-8, ISBN 978-0-4158-0179-9, 0-4158-0179-6; OCLC 317928183, 651928429.

- Via Google Books (limited preview).

- Via Google Books (limited preview).

- Film Daily (The) (daily newspaper). LCCN 41-27959.

- "Sennett 15-Reel Film Titled". Vol. 58, no. 39. February 16, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved October 24, 2025 – via Internet Archive (Media History Digital Library).

- Furmanek, Bob; Palumbo, Ron (1991). Abbott and Costello in Hollywood. Introduction by Bud Abbott, Jr., Vickie Abbott Wheeler, Chris Costello, and Paddy Costello Humphreys. New York: Putnam; Perigee Books. p. 245. LCCN 90-22097; ISBN 978-0-3995-1605-4, 0-3995-1605-0; OCLC 22710006 (all editions).

- Via Internet Archive (Kahle/Austin Foundation; Freeport Memorial Library, withdrawn).

- Giddins, Gary (2001). Bing Crosby – A Pocketful of Dreams – The Early Years: 1903–1940 (1st ed.). Little, Brown and Co. p. 456. LCCN 00-44403; ISBN 978-0-3168-8188-3, 0-3168-8188-0 (eBook), ISBN 978-0-3168-8792-2, 0-3168-8792-7 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0-3168-8645-1, 0-3168-8645-9 (paperback); OCLC 44420761 (all editions).

- Via Internet Archive (limited preview).

- "Give Citizenship to Mack Sennett". Spokane Daily Chronicle (AP). Vol. 46, no. 161 (Final Fireside ed.). March 25, 1932. p. 1 (column 3; bottom). Retrieved April 23, 2010 – via Google News.

LCCN sn86-72020 (print; 1890–1982), LCCN 96-486783 (online; 1890–1982); ISSN 2992-9873 (print), ISSN 2992-9881 (online); OCLC 14374699 (all editions).

LCCN sn86-72020 (print; 1890–1982), LCCN 96-486783 (online; 1890–1982); ISSN 2992-9873 (print), ISSN 2992-9881 (online); OCLC 14374699 (all editions). - Guy, Randor (September 6, 2014). "Comic Greats: The Man Who Founded Fun". The Hindu (blog). Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

ISSN 0971-751X; OCLC 13119119 (all editions).

ISSN 0971-751X; OCLC 13119119 (all editions). - HPLA Report (June 13, 2014). "Mack Sennett Studios Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument No. 256" (1712 N Glendale Boulevard, Echo Park). Historic Places LA: Los Angeles Historic Resources Inventory. Retrieved August 9, 2023. historicplacesla

.org .

See List of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments in Silver Lake, Angelino Heights, and Echo Park § LAHCM 256 Mack Sennett Studios.

- King, Susan (February 27, 2018). "Honorary Oscars: A Look Back at 90 Years, from Charlie Chaplin to Bob Hope to Donald Sutherland". GoldDerby. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- Koszarski, Richard (1976). Hollywood Directors: 1914–1940. Oxford University Press. LCCN 76-9262; ISBN 978-0-1950-2085-4, 0-1950-2085-5.

- Lank, Barry (January 27, 2023). "The Real Mack Sennett Studio in Echo Park – The One You Never See". The Eastsider LA. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- Los Angeles Times (The). LCCN sn89-80087 LCCN sn81-4356 (23 October 1886 – current), (25 September 1990 – current); ISSN 0458-3035 (print), ISSN 2165-1736 (online); OCLC 3638237 (all editions).

- "Mack Sennett, Famed Comedy Creator, Dies". Vol. 79, no. 331. November 6, 1960. pp. 1 (section A) & 2 (section B).

- "Blog ed. via Los Angeles Times". Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- "Print ed. via Newspapers.com".

- Movies: Mack Sennett Collection Gathers 50 Slapstick Classics Into One Set. September 29, 2014.

- "Blog ed. via Los Angeles Times". Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- "L'homme derrière le succès de Charlie Chaplin est de Danville" [The Man Behind Charlie Chaplin's Success Is from Danville]. Ici Radio-Canada Info (blog) (in Canadian French). Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. November 11, 2015. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- MacGillivray, Scott (2009) [1998]. Laurel & Hardy: From the Forties Forward. OCLC 38732251 (all editions).

- 1st ed. (1998). New York: Vestal Press. p. 161. LCCN 98-16059; ISBN 978-1-8795-1135-4, 1-8795-1135-5, ISBN 978-1-8795-1141-5, 1-8795-1141-X (paperback).

- 2nd ed. (2009) (rev. and expanded). iUniverse. p. 257. LCCN 2010-474013; ISBN 978-1-4401-7237-3, 1-4401-7237-4 (paperback), ISBN 978-1-4401-7239-7, 1-4401-7239-0 (hardcover).

- "A Wikipedia editor omitted the title, author, date, and URL". The New York Times..

- Mack Sennett is Naturalized. Vol. 81, no. 27090 (Late City ed.). March 26, 1932. p. 17 (column 4, bottom).

- ""Mack, Comedian, Killed in Crash – Moran, His Partner in Blackface Skits, Escapes Injury in Arizona Mishap — Wife and Daughter Hurt — Sennett Also in Party – Death Breaks up Vaudeville Team Together for Many Years". Vol. 83, no. 27747 (Late City ed.). AP. January 12, 1934. p. 25 (column 4).

... injured Mack Sennett, former producer of 'Bathing Beauty' film comedies"

- "Via NYTimes blog". Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- "Via TimesMachine". Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- "Pdf via TimesMachine". Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- "Permalink via TimesMachine".

- "Mack Sennett, 76, Film Pioneer Who Developed Slapstick, Dies. Keystone Kops, Custard Pies and Bathing Beauties Were Symbols of His Movies". Vol. 110, no. 37542. November 6, 1960. pp. 1 (columns 3 & 4, bottom), 88 (columns 1–3, top).

- ""Sennett Buried in Hollywood"". Vol. 110, no. 37560. November 24, 1960. p. 29 (column 5; bottom).

- Hoberman, James Lewis (September 14, 2014) [blog ed.: 12 September 2014]. "The Man Who Put the K in Kops". Vol. 163, no. 56624. p. 14 (section AR). EBSCOhost 98194308.

- "Via NYTimes blog". Retrieved August 9, 2023.

ProQuest 2213046851.

ProQuest 2213046851. - "Print transcript via ProQuest". ProQuest 1561786437

- "Via NYTimes blog". Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- Okuda, Ted; Watz, Edward (1998) [1986]. The Columbia Comedy Shorts – Two-Reel Hollywood Film Comedies, 1933–1958. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 20. LCCN 84-43241; ISBN 0-8995-0181-8; ISBN 978-1-4766-1010-8, 1-4766-1010-X (2025 eBook); OCLC 13218219 (all editions).

- 1986 ed. via Google Books (snippet view only). p. 20.

- 1998 ed. via Google Books (limited preview). ISBN 978-0-7864-0577-0, 0-7864-0577-5

- Oscars.org – Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- "Academy Awards Database". Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Search: Wrestling Swordfish. 1931.

- Search: The Loud Mouth. 1932.

- "Special Award: To Mack Sennett ...". See: 10th Academy Awards § Special Awards. March 10, 1938. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- Pantages, Lloyd (August 10, 1934). ""'I Cover Hollywood'"". [Syndicated column that ran from 1933 to 1937; King Features Syndicate. Lloyd Pantages (1907–1987) was a son of theater magnate, Alexander Pantages (1867–1936)].

- "Via Los Angeles Examiner". Vol. 79, no. 331. CDNR SN 82014773; LCCN sn82-14773; OCLC 1756176 (all editions).

- "Via San Francisco Examiner". Vol. 141, no. 41. p. 14. Retrieved October 31, 2025 – via Newspapers.com. LCCN ca10-4015, LCCN 2023-240337, LCCN sn82-6825; ISSN 2574-593X; OCLC 1764973 (all editions).

- Sennett, Mack (1954). King of Comedy. As Told to Cameron Shipp (né Ewen Cameron Shipp; 1903–1961) (1st ed.). Garden City, New York: Doubleday. LCCN 54-10768; OCLC 305664 (all editions).

- Via Internet Archive. San Francisco: Mercury House. LCCN 89-27618 (1990 re-print)

- Sherk, Warren M. (1998). The Films of Mack Sennett: Credit Documentation from the Mack Sennett Collection at the Margaret Herrick Library. Lanham, Maryland and London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Retrieved October 30, 2025 – via Internet Archive (Kahle/Austin Foundation). LCCN 97-34521; ISBN 978-0-8108-3443-9, 0-8108-3443-X.

- Silver, Charles (2009). "Send in the Clowns. An Auteurist History of Film". Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Sinnott, Michael (1999). "Mack Sennett: Canadian-American Director and Producer". Britannica. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Thomas, Bob (March 12, 1954). "Sennett Takes Sentimental Journey in Past at Reunion". Panama City News (AP). Vol. 2, no. 114. p. 11. LCCN sn96-27209; OCLC 34303827 (all editions).

- "Via "Looking for Mabel Normand"". Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- "Via Newspapers.com".

- Walker, Brent E. (2010). Mack Sennett's Fun Factory: A History and Filmography of His Studio and His Keystone and Mack Sennett Comedies, with Biographies of Players and Personnel (2 Vols.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. LCCN 2009-30637; ISBN 978-0-7864-5707-6, 0-7864-5707-4, ISBN 978-0-7864-7711-1, 0-7864-7711-3, ISBN 978-0-7864-3610-1, 0-7864-3610-7.

- Vol. 2 – via Internet Archive (Kahle/Austin Foundation; Sharon Public Library, discarded).

- Walker, Brent E. (September 3, 2014). "The Survival of Mack Sennett's Comedies" (blog founded in 2002 by Jeffery Masino). Los Angeles: Flicker Alley, LLC. Archived from the original on April 15, 2024. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Lahue, Kalton Carroll (1971). Mack Sennett's Keystone: The Man, the Myth and the Comedies. New York: A.S. Barnes and Company. LCCN 78-146763; ISBN 978-0-4980-7461-5, 0-4980-7461-7; OCLC 227346 (all editions).

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Mack Sennett at the Internet Archive

- Mack Sennett at IMDb

- Mack Sennett at Find a Grave

- Mack Sennett at Virtual History