Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

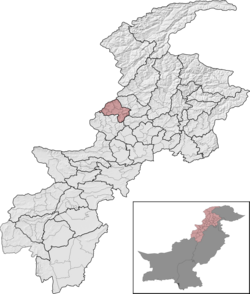

Bajaur District

View on WikipediaBajaur District (Pashto: باجوړ ولسوالۍ, Urdu: ضلع باجوڑ), formerly Bajaur Agency, is a district in the Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. Prior to 2018, Bajaur Agency was the northernmost component of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a semi-autonomous region along the Afghanistan–Pakistan border. In May 2018, FATA was merged into the larger Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK) in an attempt to bring stability to the region, redesignating Bajaur Agency to Bajaur District.

Key Information

The district lies on Pakistan's western border, sharing a 52 km border with Afghanistan's Kunar Province, and lies 35 mi (56 km) north of the Torkham border crossing linking Jalalabad and Peshawar. 498 square kilometer miles in size, Bajaur occupies a small mountain basin and is into seven tehsil (subdistricts) with its district headquarters in the town of Khar, in the district's center. According to the 2017 Pakistani census, Bajaur District has a population of 1,090,987.

Geography

[edit]

Before the 2018 incorporation of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas' (FATA) tribal agencies into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK), Bajaur Agency was both the northernmost and smallest of the seven tribal agencies, bordering the slightly larger Kurram Agency to its south.

Bajaur is about 45 miles (72 km) long and 20 miles (32 km) wide. It lies at a high elevation to the east of the Kunar Valley of Afghanistan from which it is separated by a continuous line of rugged frontier hills. The old road from Afghanistan's Kabul to Pakistan went through Bajaur before a new pass, Khyber Pass, was constructed.

To the south of Bajaur is the district of Mohmand. To the east, beyond the Panjkora River, are the hills of Swat District. On its east side, there is the district of Malakand, while on its northeast is an intervening watershed between Bajaur and Dir.

Nawagai is the chief town of Bajaur; the Khan of Nawagai was previously under the British protection for the purpose of safeguarding of the Chitral road.[5] [citation needed]

An interesting feature in the topography is a mountain spur from the Kunar range.

The drainage of Bajaur flows eastwards, starting from the eastern slopes of the dividing ridge, which overlooks the Kunar and terminating in the Panjkora river, so that the district lies on a slope tilting gradually downwards from the Kunar ridge to the Panjkora.

Jandol, one of the northern valleys of Bajaur, has ceased to be of political importance since the 19th century, when a previous chief, Umra Khan, failed to appropriate himself Bajaur, Dir and a great part of the Kunar valley. It was the active hostility between the Amir of Kabul (who claimed sovereignty of the same districts) and Umra Khan that led, firstly to the demarcation agreement of 1893 which fixed the boundary of Afghanistan in Kunar; and, secondly, to the invasion of Chitral by Umra Khan (who was no party to the boundary settlement), and the siege of the Chitral fort in 1895.[5]

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]The area was the site of the ancient Gandhara kingdom of Apraca from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE, and a stronghold of the Aspasioi, a western branch of the Ashvakas (q.v) of the Sanskrit texts who had earlier offered stubborn resistance to the Macedonian invader Alexander the Great in 326 BCE. The whole region came under Kushan control after the conquests of Kujula Kadphises during the first century CE.[6][7]

Alexander the Great

[edit]Alexander turned south from Aornus and continued march towards the Indus, but the greatest surprise during the march came when he neared the town of Nysa (former name of Bajaur). The local people and even the flora seemed strangely out of place in these mountains. The Nysains placed their dead in cedar coffin in the trees - some of which Alexander accidentally set on fire - and made wine from grapes, unlike other tribes in the area.[8] The Acuphis, the chief man of the city, who has been sent to them along with other thirty leaders, begged him not to harm their towns as they were descendants of settlers that the god Dionysus placed their generation before. Their prolific ivy, a plant sacred to Dionysus that nowhere else in the mountain, was proof they were the people blessed by god. Then they were only commanded to give him 300 cavalry, after which he restored their freedom and allow them to live under their own laws, having made Acuphis governor of the city. Alexander took his son and grandson as hostages. He sacrificed there to Bacchus under this god's others name of Dionysus.[9]

Bajaur casket

[edit]The Bajaur casket, also called the Indravarma reliquary, year 63, or sometimes referred to as the Avaca inscription, is an ancient reliquary from the area of Bajaur in ancient Gandhara, in the present-day Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan. It is dated to around 5-6 CE. It proves the involvement of the Scythian kings of the Apraca, in particular King Indravarman, in Buddhism. The casket is made of schist.

Mughal–Afghan wars

[edit]Bajaur massacre

[edit]In 1518, Babur had invested and conquered the fortress of Bajaur, The Gabar-Kot from Sultan Mir Haider Ali Gabari the Jahangirian Sultan and gone on to conquer Bhera on the river Jhelum, a little beyond the salt ranges. Babur claimed these areas as his own, because they had been part of Taimur's empire. Hence, "picturing as our own the countries once occupied by the Turks",[10] he ordered that "there was to be no overrunning or plundering [of the countryside]".[10] It may be noted that this applied to areas which did not offer resistance, because earlier, at Bajaur, where the Pashtun tribesmen had resisted, he had ordered a general massacre, with their women and children being made captive.[10]

Babur justifies this massacre by saying, "the Bajauris were rebels and at enmity with the people of Islam, and as, by heathenish and hostile customs prevailing in their midst, the very name of Islam was rooted out...".[11]

As the Bajauris were rebels and inimical to the people of Islam, the men were subjected to a general massacre and their wives and children were made captive. At a guess, more than 3,000 men met their death. We entered the fort and inspected it. On the walls, in houses, streets and alleys, the dead lay, in what numbers! Those walking around had to jump over the corpses.[12][a]

Battle of Malandari Pass

[edit]From late 1585 into 1586, forces of the Mughal army led by Zain Khan Koka, at the direction of the Mughal emperor Akbar the Great, waged a military campaign to subdue the Yusufzai tribes of Bajaur and Swat.[13] The Mughal operation, which culminated in the Battle of the Malandari Pass resulted in an Afghan victory and a military embarrassment for Akbar.

Princely state

[edit]Bajaur was a princely state run by the Nawab of Khar. The last and most prominent Nawab was Abdul Subhan Khan, who ruled until 1990.[14]

Recent decades

[edit]During the Soviet invasion in the 1980s, the area was a critical staging ground for Afghan and local mujahideen to organise and conduct raids. It still hosts a large population of Afghan refugees sympathetic to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a mujahideen leader ideologically close to the Arab militants. Today,[when?] the United States believes militants based in Bajaur launch frequent attacks on American and Afghan troops in Afghanistan.

Counterterrorism

[edit]Airstrikes

[edit]An aerial attack, executed by the United States targeting Ayman al-Zawahiri, took place in a village in Bajaur Agency on January 13, 2006, killing 18 people.[15] Al-Zawahiri was not found among the dead and the incident led to severe outrage in the area.[citation needed]

On October 30, 2006, 80 people were killed in Bajaur when Pakistani forces attacked a religious school they said was being used as a militant training camp.[16] There are many unconfirmed reports that the October attack was also carried out by the United States or NATO forces, but was claimed by Islamabad over fears of widespread protest similar to those after the US bombing in January 2006.[17] Maulana Liaqat, the head of the seminary, was killed in the attack.[citation needed] Liaqat was a senior leader of the pro-Taliban movement Tanzim Nifaz Shariat Mohammadi (TNSM), that spearheaded a violent Islamic movement in Bajaur and the neighbouring Malakand areas in 1994. The TNSM had led some 5,000 men from the Pakistani areas of Dir, Swat and Bajaur across the Mamund border into Afghanistan in October 2001, to fight US-led troops.[citation needed] In what is thought to be a reprisal for the October strike in Bajaur, in November, a suicide bomber killed dozens in an attack on an army training school in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.[18]

Bajaur offensive

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (February 2024) |

Loi sum is on a strategic location, road come from four sides, (khar, Nawagi, Tangai and Inzari), so approach was easy from Charmang and Ambar. That was the reason that this area was affected mostly. A military offensive by the military of Pakistan (FC and Leaves) was launched in early 8 August 2008 to retake the border crossing near the town of Loi-Sum, 12 km from khar[19] from militants loyal to Tehrik-e-Taliban, the so-called Pakistani Taliban.[20] In the two weeks following the initial battle, government forces pulled back to Khar and initiated aerial bombing and artillery barrages on presumed militant positions, which reportedly has all but depopulated Bajaur and parts of neighbouring Mohmand Agency, with an estimated 300,000 fleeing their homes.[20] The estimate of casualties ran into the hundreds.[20] The offensive was launched in the wake of Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani's visit to Washington in late July, and is believed by some to be in response to U.S. demands that Pakistan prevent the FATA being used as a safe haven by insurgents fighting American and NATO troops in Afghanistan.[20] However, the offensive was decided by the military, not the civilian government.[21] The bloody bombing of Pakistan Ordnance Factories in Wah on August 21, 2008, came according to Maulvi Omar, a spokesman for the Pakistani Taliban, as a response to the Bajaur offensive.[22][23] after a few weeks, the Pak army came to battlefield. In an initial way toward the Loi sum Taliban did not resist and let them to come to middle position, when they reach to Rashakai, (3–4 km from Loi sum) Taliban started to attack them but the Army was far stronger than their expectation. For several weeks they stayed in Rashakai, then 1st attempt Army come to loi sum, stay for whole day and come back to Rashakai, In 2nd attempt was the same, and 3rd attempt they come to loi sum and took the control of the area. Army continues there journey, control the main road of Bajaur from Khar to Nawagi, and the peripheral areas were still in the hold of Taliban. After nine months of vigorous clashes between government security forces and Taliban, military forces have finally claimed to have forced militants out of Bajaur Agency, and advanced towards strongholds of Taliban in the region. According to figures provided by the Government of Pakistan, 1,600 militants were killed and more than 2,000 injured, while some 150 civilians also died and about 2,000 were injured in the fighting. The military operation forced more than 300,000 people to flee their homes and take shelter in IDP camps in settled districts of the province. To date, more than 180,000 IDPs have returned to their homes in Bajaur Agency, facing widespread destruction to their lives, livelihoods and massive unemployment. In August, 2012, the Pakistani Army de-listed Bajaur as conflict zone.[24]

Media coverage

[edit]From 2008 through 2010, Al Jazeera English produced multiple features of the ongoing conflict between Pakistani military forces and Taliban militants in the agency.[25][26][27]

In early 2013, VICE News founder Shane Smith accompanied and documented a raid on suspected Taliban fighters by the Pakistani Frontier Corps' Bajaur Scouts in Bajaur Agency.[28]

Islamic State

[edit]As of March 2024, the Islamic State's Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) maintains an operational presence in Bajaur, conducting 4 attacks in 2021, 21 attacks in 2022, and 18 in 2023. The majority of ISIS-K attacks in Bajaur occur in Mamond tehsil, followed by Inayat Kali, Salarzo, and Khar tehsils.[29]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Bajaur District is currently subdivided into seven tehsils (sub-districts).[30]

| Tehsil | Area

(km²)[31] |

Pop.

(2023) |

Density

(ppl/km²) (2023) |

Literacy rate

(2023)[32] |

Union Councils | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bar Chamarkand Tehsil | 13 | 3,574 | 104.41 | 23.81% | Western tip | |

| Barang Tehsil | 159 | 90,082 | 100.27 | 23.39% | Southeast | |

| Khar Bajaur Tehsil | 238 | 301,778 | 102.81 | 33.28% | Central and south-central | |

| Mamund Tehsil | 250 | 358,190 | 103.29 | 24.48% | Northwest | |

| Nawagai Tehsil | 216 | 93,850 | 103.2 | 27.39% | West | |

| Salarzai Tehsil | 220 | 316,767 | 101.01 | 19.90% | North-central | |

| Utman Khel Tehsil | 194 | 123,719 | 100.66 | 31.50% | East |

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 320,985 | — |

| 1961 | 280,200 | −1.35% |

| 1972 | 364,050 | +2.41% |

| 1981 | 289,206 | −2.52% |

| 1998 | 595,227 | +4.34% |

| 2017 | 1,090,987 | +3.24% |

| 2023 | 1,287,960 | +2.80% |

| Sources:[33][3] | ||

As of the 2023 census, Bajaur district has 181,699 households and a population of 1,287,960. The district has a sex ratio of 102.14 males to 100 females and a literacy rate of 26.26%: 39.89% for males and 12.29% for females. 466,054 (36.32% of the surveyed population) are under 10 years of age. The entire population lives in rural areas.[3]

Population

[edit]| Overall District | Area | 1998 Population | 2017 Population | 2023 Population | Population Density | Mean Annual Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajaur District | 1,290 km2 | 595,227 | 1,090,987 | 1,287,960 | 998.4 per km2 | |

| Tehsil | Area | 1998 Population | 2017 Population | 2023 Population | Population Density | Mean Annual Growth |

| Mamund Tehsil | 250 km2 | 168,283 | 311,373 | 358,190 | 1432.76 per km2 | |

| Salarzai Tehsil | 220 km2 | 141,750 | 267,636 | 316,767 | 1,439.85 per km2 | |

| Khar Bajaur Tehsil | 238 km2 | 116,196 | 246,875 | 301,778 | 1,267.97 per km2 | |

| Utman Khel Tehsil | 194 km2 | 58,348 | 107,248 | 123,719 | 637.73 per km2 | |

| Nawagai Tehsil | 216 km2 | 57,264 | 78,494 | 93,850 | 434.49 per km2 | |

| Barang Tehsil | 159 km2 | 50,139 | 76,493 | 90,082 | 566.55 per km2 | |

| Bar Chamer Kand Tehsil | 13 km2 | 3,247 | 2,868 | 3,574 | 274.92 per km2 | |

| Source: Pakistani Bureau of Statistics (2017 Pakistan Census)(2023 Pakistan Census) | ||||||

Nationality

[edit]Bajaur District is 99.91% Pakistani with a relatively small population of inhabitants identifying as of a non-Pakistani nationality.

| Gender | Pakistani | Pakistani (%) | Other | Other (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1,281,941 | 99.91% | 1,172 | 0.09% |

| Male | 647,930 | 99.92% | 543 | 0.08% |

| Female | 633,996 | 99.9% | 629 | 0.1% |

| Transgender | 15 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| Source: Pakistani Bureau of Statistics (2023 Pakistan Census) | ||||

Tribal affiliation

[edit]Bajaur is inhabited near exclusively by Tarkanri (Mamund, Kakazai, Wur and Salarzai) Pashtuns, as well as a smaller population of Utmankhel, Wazir, Safi, and Yousafzai tribes. Gurjar and Swatis are also present. The Utmankhel are at the southeast of Bajaur, while Mamund are at the southwest, and the Tarkalanri are at the north of Bajaur. Its border with Afghanistan's Kunar province makes it of strategic importance to Pakistan and the region.

Language

[edit]The mother tongue of the majority of Bajauris are expectedly 99.85% Pashto, reflective of the indigenous Pashtun (also 'Pakthtun') population that inhabits much of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK, for which the province derives its name) and eastern Afghanistan. Other residents are first-language Urdu speakers, the national language of Pakistan, while relatively small numbers are native Balochi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, Saraiki, Brahvi (Brahui), and Punjabi speakers.[34]

| Overall District | Urdu | Punjabi | Sindhi | Pashto | Balochi | Kashmiri | Saraiki | Hindko | Brahvi | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajaur District | 372 | 145 | 86 | 1,281,221 | 1,059 | 15 | 12 | 21 | 1 | 181 |

| Tehsil | Urdu | Punjabi | Sindhi | Pashto | Balochi | Kashmiri | Saraiki | Hindko | Brahvi | Others |

| Mamund Tehsil | 84 | 4 | 22 | 356,609 | 383 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 31 |

| Salarzai Tehsil | 67 | 10 | 19 | 315,350 | 257 | 6 | 1 | - | - | 35 |

| Khar Bajaur Tehsil | 159 | 126 | 31 | 298,846 | 182 | 3 | 7 | 19 | - | 12 |

| Utman Khel Tehsil | 22 | 3 | 5 | 123,417 | 88 | 1 | - | - | - | 51 |

| Nawagai Tehsil | 20 | - | 2 | 93,591 | 78 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Barang Tehsil | 20 | 2 | 6 | 89,837 | 69 | 2 | - | - | - | 45 |

| Bar Chamer Kand Tehsil | - | - | 1 | 3,571 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 45 |

| Source: Pakistani Bureau of Statistics (2023 Pakistan Census); Mother tongues only | ||||||||||

Religion

[edit]Bajaur District is nearly entirely Muslim.[35]

| Overall District | Muslim | Muslim (%) | Christian | Christian (%) | Hindu | Hindu (%) | Ahmadi | Ahmadi (%) | Other | Other (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajaur District | 1,279,889 | 99.75% | 3,068 | 0.24% | 50 | ~0% | 21 | ~0% | 85 | 0.01% |

| Tehsil | Muslim | Muslim (%) | Christian | Christian (%) | Hindu | Hindu (%) | Ahmadi | Ahmadi (%) | Other | Other (%) |

| Mamund Tehsil | 355,762 | 99.62% | 1,329 | 0.37% | 15 | ~0% | 11 | ~0% | 18 | 0.01% |

| Salarzai Tehsil | 314,978 | 99.76% | 716 | 0.23% | 23 | 0.01% | 4 | ~0% | 24 | 0.01% |

| Khar Bajaur Tehsil | 298,872 | 99.83% | 479 | 0.16% | 7 | ~0% | 1 | ~0% | 26 | 0.01% |

| Utman Khel Tehsil | 123,365 | 99.82% | 216 | 0.17% | 1 | ~0% | 2 | ~0% | 3 | ~0% |

| Nawagai Tehsil | 93,466 | 99.74% | 224 | 0.24% | 2 | ~0% | 0 | 0% | 14 | 0.01% |

| Barang Tehsil | 89,873 | 99.88% | 103 | 0.11% | 2 | ~0% | 3 | ~0% | 0 | 0% |

| Bar Chamer Kand Tehsil | 3,573 | 99.97% | 1 | 0.03% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Source: Pakistani Bureau of Statistics (2023 Pakistan Census) | ||||||||||

Governance and politics

[edit]Constituents of Bajaur District are politically represented locally through elected union councils, town governments, and tehsil governments. The district government includes a deputy commissioner, additional deputy commissioner, two assistant commissioners, tehsildars (heads of tehsil), district agricultural officer, district educational officer, medical superintendent, district coordination officer, assistant director for local government, and district population welfare officer.[36]

Provincial Assembly Members

[edit]At the provincial level, constituents are represented by the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, an elected unicameral legislature of 145 seats in the provincial capital of Peshawar, with 115 general seats, 26 reserved for women, and 4 reserved for non-Muslims.

12th Provincial Assembly

[edit]The 8 February 2024 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial election, based on the results of a 2023 digital census, granted Bajaur District a fourth seat in the Provincial Assembly.

A PTI candidate for the new PK-22 Bajaur-IV constituency election, Rehan Zeb Khan, was shot and killed by an ISIS-K attacker while in his car in a market in Bajaur District, leading to the postponement of that constituency's election, as well as in NA-8.[37]

| Constituency | Elected Member | Party affiliation | Votes | Contender | Contender Party Affiliation | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK-19 Bajaur-I | Hamid Ur-Rehman | Independent* | 23,044 | Khalid Khan | Independent* | 13,571 |

| PK-20 Bajaur-II | Wahid Gul | 13,039 | Anwar Zeb Khan | Independent* | 12,903 | |

| PK-21 Bajaur-III | Sardar Khan | 16,844 | Ajmal Khan | Independent* | 15,713 | |

| PK-22 Bajaur-IV | Election postponed due to ISIS-K assassination of an independent candidate Rehan Zeb Khan (member of PTI but not given ticket.)[37] | |||||

11th Provincial Assembly

[edit]| Constituency | Member | Age | Date of birth | Religion | Education | Profession | Party affiliation | Term start | Term end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK-100 Bajaur-I | Anwar Zeb Khan | 55 | 3 April 1970 | Islam | Unknown | Landlord | 27 August 2019 | 18 January 2023 | |

| PK-101 Bajaur-II | Ajmal Khan | 56 | 15 January 1970 | Islam | B.S. Civil Engineering | Business | 27 August 2019 | 18 January 2023 | |

| PK-102 Bajaur-III | Siraj Uddin | 64 | 6 June 1961 | Islam | B.A. Unknown Major | Unknown | 27 August 2019 | 18 January 2023 |

National Assembly Members

[edit]A PTI candidate for the NA-8 constituency election, Rehan Zeb Khan, was shot and killed by an ISIS-K attacker while in his car in a market in Bajaur District, leading to the postponement of that constituency's election, as well as in NA-8.[37]

| 15th National Assembly (2018–2023) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constituency | Elected Member | Party affiliation | Term start | Term end |

| NA-40 Tribal Area-I | Gul Dad Khan | 13 August 2018 | 9 August 2023 | |

| NA-41 Tribal Area-II | Gul Zafar Khan | 13 August 2018 | 9 August 2023 | |

| 14th National Assembly (2013–2018) | ||||

| NA-43 Bajaur | Bismillah Khan | Independent | 1 June 2013 | 31 May 2018 |

| NA-44 Bajaur | Shahabuddin Khan | 1 June 2013 | 31 May 2018 | |

| 13th National Assembly (2008–2013) | ||||

| NA-43 Bajaur | Shaukatullah Khan | Independent | 17 March 2008 | 8 April 2013 |

| NA-44 Bajaur | Akhundzada Chitan | Independent | 17 March 2008 | 16 March 2013 |

| 12th National Assembly (2002–2007) | ||||

| NA-43 Bajaur | Sheikh Alhadees Maulana Muhammad Sadiq | Independent | 16 November 2002 | 15 November 2007 |

| NA-44 Bajaur | Sahibzada Haroon ur-Rashid | Independent | 16 November 2002 | 15 November 2007 |

| 11th National Assembly (1997–1999) | ||||

| NA-32 Tribal Area VI | Haji Lal Karim | Independent | 15 February 1997 | 14 October 1999 |

| 10th National Assembly (1993–1996) | ||||

| NA-32 Tribal Area VI | Bismillah Khan | Independent | 15 October 1993 | 5 November 1996 |

| 9th National Assembly (1990–1993) | ||||

| NA-32 Tribal Area VI | Haji Lal Karim | Independent | 3 November 1990 | 18 July 1993 |

| 8th National Assembly (1988–1990) | ||||

| NA-32 Tribal Area VI | Bismallah Khan | Independent | 30 November 1988 | 6 August 1990 |

| 7th National Assembly (1985–1988) | ||||

| NA-32 Tribal Area VI | Abdul Subhan Khan | Independent | 20 March 1985 | 29 May 1988 |

| 6th National Assembly (1977–1977) | ||||

| NA-32 Tribal Area VI | Abdul Subhan Khan | Independent | 28 March 1977 | 5 July 1977 |

| 5th National Assembly (1972–1977) | ||||

| NW-25 Tribal Area VII | Abdul Subhan Khan | Independent | 14 April 1972 | 10 January 1977 |

| Notes: NW denotes West Pakistan before Bangladeshi (East Pakistan) independence | ||||

Education

[edit]In Bajaur, the total number of SSC-level schools registered with Malakand Board are 150 (61 government-run, 89 private-run). The number of HSSC-level colleges are 56 (18 government-run, 38 private-run).[38]

Education rank

[edit]In district school education rank of Pakistan, the position of is going downward, according to the Alif Ailaan ranking, the rank of Bajaur in 2014,[39] 2015[40] and 2016[41] is the following

| Rank/Position | District/Agency | Province/Territory | Education Score | Enrolment score | Learning score | Retention score | Gender Parity score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47(2014) | Bajaur | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 74.10 | 75.00 | 94.77 | 80.57 | 46.08 |

| 99(2015) | Bajaur | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 57.43 | 59.59 | 34.32 | 63.25 | 72.56 |

| 131(2016) | Bajaur | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 42.42 | 52.80 | 36.57 | 20.00 | 60.32 |

Tourism

[edit]Bajaur is located near swat and District Dir, so the climates of these districts are comparatively same.

Koh-i-Mor

[edit]Koh-i-Mor is the highest peak in Bajaur. It is also called three peak mountain. Its top is covered with snow in winter and clouds are touching its peak. The peak of Koh-i-Mor is visible from the Peshawar valley when there is no clouds or haze.

It is an historical mountain, its history is found 2000 year back, here at the foot of the Koh-i-Mor mountain, that Alexander the Great founded the ancient city of Nysa and the Nysaean colony, traditionally said to have been founded by Dionysus. The Koh-i-Mor has been identified as the Meros of Arrian's history — the three-peaked mountain from which the god issued.

For hiking, like Jahaz Banda and Fairy meadow, Koh-i-Mor is the best, it is about 4 hours trekking non-local and 2,5 for locals. On the way you will see a lot of variation. In some places you will pass through thick forest of fine trees, some places have shrubs, and some place you will see some different kinds of trees.

People are living in Koh-i-Mor up-to near the top. These people have simple houses with a single room, there is no extra boundary wall. Rooms are made like caves in mountain. Majority of them are shepherds.

Chenarran (platane Orientalis)

[edit]At the base of Koh-i-Mor a lot of chenar trees along with spring. Locals people are coming here and enjoy the nature, making their own cooking, some have load speakers, music, etc. majority people come along with their families.

Gabar Chenna

[edit]It is situated in Tehsil Salarzai, it has snowy water, people are come from all over the Bajaur and DIR to enjoy it especially in Ramadan and Eids. It is a historically spring, once here was a undefeated king ....

Charmang Hill

[edit]The Charmang hills in Bajaur are covered with pine trees and also the roads is made up to top of hill.[citation needed] The road goes on top of hill from bottom to top. In winter, the whole mountain is covered with snow for months.[citation needed]

Raghagan DAM

[edit]Raghagan Dam is situated in Tehsil Salarzai. It a tourist spot nowadays. Boats are present here for tourists.

Economy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

Agriculture

[edit]Bajaur is a semi-independent in agriculture field, The soil is fertile but the no proper irrigation system. Harvest Crops; People grow wheat, maze and rices in some areas. All the crops is mainly dependent on rain. Vegetable and Fruits; The different types of vegetables are growing in Bajaur. Potato, tomato, onion, lady fingers, spinach, and orange parsimon, etc

Marble

[edit]Marbles are found in various regions, mainly in Inzari and Nawagai. There are different types of marble supper white, Badle etc. In the local areas are marble factories, cut to into different sizes of the base of demand, and supply to all over the country and even abroad.

Marble factory

[edit]The marble cutting factories are found in Shaikh kali and Umary. The supply to the factories of marble mainly from the local mountains and they also bring the marble from ambar and Zairat. These different types and variety of marble then supply all over the country

Nephrite

[edit]Nephrite (jade) is the precious stone, Rs 3000–5000 per kg. The mines are found in Inzari and some area in Utmankhail tehsil. It exports mainly to China, The Chinese thought so too, and for thousands of years, nephrite articles had a special value and signature and skilled artisans carved increasingly intricate designs. Maybe because it was so rare in China, yet useful for its toughness, nephrite became the status symbol of the rulers, considered imperial stone.

Olives and olive oil

[edit]The KPK government has started olive production projects in the Bajaur district. Previously, many wild olive trees are present in the area having no such importance. They use agricultural techniques to convert these wild trees into more farmer friendly and productive plants. With new projects of planting olive trees on more than 150000 acres of land, the Bajaur district will be the olive hub of Pakistan.[42] Moreover, the district administration has installed olive oil extraction machine for locals. this machine started producing olive oil this year. More than 200 kg of oil has been extracted which is just a beginning. In coming years you will see huge transformation. These projects will change the fate and economical status of the district. The locals will have more new employment opportunities cause reduction in unemployment in the tribal area.

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]- Bajaur Campaign

- 1961 Pakistani Bombing of Batmalai

- Damadola airstrike of January 13, 2006

- Chenagai airstrike of October 30, 2006

- Bajaur offensive

- Kakazai

- Salarzai

Notes

[edit]- ^ Thomas Holdich writing in 1911 in Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.) stated that "The Gazetteers and Reports of the Indian government contain nearly all the modern information available about Bajour. The autobiography of Baber (by Leyden and Erskine) gives interesting details about the country in the 16th century. For the connexion between the Kafirs and the ancient Nysaeans of Swat, see R. G. S. Journal, vol. vii., 1896" (Holdich 1911).

References

[edit]- ^ "KP Minister inaugurates IT skills training center at Qadafi". Pakistan Observer. 2023-12-29. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

- ^ Historical and administrative profile of the Bajaur Agency (.fata.gov.pk)

- ^ a b c "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 1" (PDF). www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Literacy rate, enrolments, and out-of-school population by sex and rural/urban, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ a b Holdich 1911.

- ^ Hill, John E. (2015-03-18). "Appendix G". Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome'. Vol. II (2nd ed.). pp. 65–75.

- ^ Yu, Taishan (1998). A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania. p. 160.

- ^ Romm, James S.; Mensch, Pamela (2005-03-11). Alexander The Great: Selections from Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, and Quintus Curtius. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60384-333-1.

- ^ Ussher, James (2003-10-01). The Annals of the World. New Leaf Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-61458-255-7.

- ^ a b c Chandra, p. 22.

- ^ Chandra, p. 23.

- ^ Babur, p. 207.

- ^ Shukla, Ashish (2015). "The Pashtun Tribal Identity and Codes: At Odds with Pakistan's Post-9/11 Policies" (PDF). THAAP Journal: 47.

- ^ "About us/district profile". Deputy Commissioner Bajaur. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Pakistani elders killed in blast". BBC. 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Khan, M Ilyas (2006-10-30). "'Shock and awe' on Afghan border". BBC. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ "Pakistan's Tribal Areas". New York, NY, USA: Council on Foreign Relations. 2007-10-26. Archived from the original on 2009-05-30. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ^ "Suicide bomber attacks policemen". BBC. 2006-11-17. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Khan, Hasbanullah (AFP) (August 8, 2008). "Bajaur battle kills 10 troops, 25 militants". Daily Times. Lahore, Pakistan. Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ a b c d Cogan, James (August 23, 2008). "Military offensive displaces 300,000 in north-west Pakistan". Oak Park, MI, USA: World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ Sappenfield, Mark (2008-09-24). "U.S. and Pakistan: different wars on terror". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston, MA, USA.

- ^ Anthony, Augustine (2008-08-21). "Blasts near Pakistan arms plant kill 59". London, UK: Reuters. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ "Pakistan: 100 die in 'Taliban' suicide bombings". CNN International. 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ Ali, Zulfiqar (2012-08-06). "South Waziristan operation: Only Sararogha cleared in three years". Dawn. Karachi, Pakistan: Pakistan Herald Publications.

- ^ Strategic town of Bajaur is in Pakistan hands - 26 Oct 08. Al Jazeera English. 26 October 2008.

- ^ Pakistan 'takes over' Taliban base in Bajaur. Al Jazeera English. 3 March 2010.

- ^ Battle for Bajaur tests Pakistan - 29 Sept 2008. Al Jazeera English. 29 September 2008.

- ^ Smith, Shane (19 April 2013). World's Most Dangerous Border: Bajaur Raid (VICE on HBO Ep. #2 Extended) (Television production).

- ^ Islamic State an-Naba Newsletter; Issues #305–#432

- ^ "DISTRICT AND TEHSIL LEVEL POPULATION SUMMARY WITH REGION BREAKUP" (PDF). pbscensus.gov. 2018-03-26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-26. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ "TABLE 1 : AREA, POPULATION BY SEX, SEX RATIO, POPULATION DENSITY, URBAN POPULATION, HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ "LITERACY RATE, ENROLMENT AND OUT OF SCHOOL POPULATION BY SEX AND RURAL/URBAN, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ "Population by administrative units 1951-1998" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 11" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 9" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Bajaur: Information Directory". Deputy Commissioner Bajaur.

- ^ a b c Saifi, Sophia (1 February 2024). "Pakistan election candidate shot dead as violence escalates ahead of nationwide vote". CNN.

- ^ "BISE Malakand - Registered Institutions". bisemalakand.edu.pk. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Saeed Memon, Asif; Saman Naz, SDPI; Alif Ailaan (2015). "ALIF AILAAN PAKISTAN DISTRICT EDUCATION RANKINGS 2015" (PDF). PDF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Alif Ailaan (2014). "Pakistan District Education Rankings" (PDF). PDF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2022.

- ^ Saman Naz; Saeed Memon, Asif; Minhaj ul Haque; Umar Nadeem; Ghamae Jama; Aleena Khan (2016). "PAKISTAN DISTRICT EDUCATION RANKINGS 2016" (PDF). PDF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2022.

- ^ "From Terrorists Hub to the Olive Oil Producing Hub, A Story of Bajaur". 31 October 2020.

References

[edit]- Babur, Zahir Uddin Muhammad, Babur-Nama: Journal of Emperor Babur, Penguin

- Chandra, Satish, Medieval India (Part two), pp. 22–23

- Profiles of Pakistan's Seven Tribal Agencies

- 1998 Census report of Bajaur Agency. Census publication. Vol. 137. Islamabad: Population Census Organization, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan. 2001.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Holdich, Thomas Hungerford (1911). "Bajour". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 226.

Bajaur District

View on GrokipediaBajaur District is an administrative district in the Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan, with its headquarters at Khar.[1][2] Formerly known as Bajaur Agency within the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, it was integrated into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa via the 25th Constitutional Amendment in 2018, ending its semi-autonomous tribal status.[1][3] The district spans 1,290 square kilometers of predominantly hilly terrain within a mountainous basin, sharing a 52-kilometer border with Afghanistan's Kunar Province.[1][4] As of the 2023 census, its population stands at 1,287,960, making it densely populated relative to its size among former tribal districts.[5] Bajaur is divided into two sub-divisions—Khar and Nawagai—and eight tehsils, including Khar Bajaur, Loe Mamund, and Bar Chamer Kand.[1][4] The area is home to Pashtun tribes such as the Tarkani and Utmankhel, who have historically dominated its social structure. Economically, the district relies on subsistence agriculture in its narrow valleys, supplemented by limited trade across the porous border, though development has been hampered by geographic isolation and insecurity.[6] The district's defining characteristic has been its role as a hotspot for Islamist militancy, fueled by its rugged terrain and proximity to Afghanistan, prompting repeated Pakistani military operations to dismantle militant networks, including major offensives in 2008–2009 that displaced hundreds of thousands.[7][8] Despite these efforts, sporadic attacks persist, as evidenced by a 2023 suicide bombing at a political rally in Khar that killed over 50 people and was claimed by ISIL affiliates.[9] The merger into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa aimed to extend governance reforms and infrastructure, but implementation challenges, including resistance to central authority, continue to shape its trajectory.[1]

Geography

Physical Features

Bajaur District features a predominantly hilly and mountainous terrain, characterized by rugged hills, narrow valleys, and scattered fertile plains forming an intricate maze of landforms. The district spans approximately 1,290 square kilometers, extending about 72 kilometers in length and 32 kilometers in breadth.[10][4] Northern elevations reach up to 3,000 meters in mountain ranges, gradually descending southward into lower hills and basins.[11][12] A notable topographic element is a spur extending eastward from the Kunar Range, which influences local drainage patterns and divides the landscape.[13] The highest peak, Koh-i-Mor (also known as Kimor), rises in the Baran tehsil and is distinguished by its three summits, often snow-capped in winter. Average district elevation approximates 1,172 meters, with denuded hills prevalent due to arid conditions and historical deforestation, though about 45% of the area remains hilly with some afforestation.[14][15][1] Drainage primarily flows eastward from the slopes of dividing ridges toward the Panjkora River, which traverses the southern and eastern boundaries before joining the Swat River. The principal waterway within Bajaur is the Bajaur River (locally called Rud), flowing southwest to northeast and merging with the Munda Khwar. Numerous smaller torrents and streams, including Salarzai, Nawagai, Mamund, and Batwar Khwar, originate in the hills, supporting limited irrigation but prone to seasonal flooding.[4][11][16]Climate and Environment

Bajaur District exhibits an extreme climate shaped by its rugged, mountainous terrain. Winters span from November to the end of March, characterized by severe cold where temperatures frequently fall below freezing.[1] Summers commence in May and extend through September, featuring hot and dry conditions with maximum temperatures climbing to 110°F (43°C).[1] Precipitation remains low annually, though monsoon influences bring rainfall primarily between July and mid-September.[1] The district's environment supports notable biodiversity despite pressures from human activity. Flora in subregions like Arang Valley encompasses 218 plant species distributed across 77 families and 179 genera, reflecting adaptations to varied elevations and microclimates.[17] Avian diversity includes 83 species from 15 orders and 40 families, with Passeriformes comprising the most abundant order, inhabiting forests, valleys, and wetlands.[18] Natural forests persist in higher elevations, such as around Kohimore mountain, contributing to the ecological framework.[19] Environmental challenges predominate, including widespread deforestation over the past four to five decades driven by timber harvesting and fuelwood demand, which has eroded former vegetative cover and heightened landslide risks.[20] Soil erosion and water scarcity compound these issues, with climate change intensifying heatwaves, reduced groundwater recharge, and agricultural strain in this arid-prone area.[21] Unplanned groundwater extraction and overgrazing further degrade rangelands and surface water potential, underscoring the need for sustainable resource management.[22]History

Ancient and Pre-Islamic Periods

Bajaur formed part of the ancient Gandhara region, an Indo-Aryan cultural sphere centered in northwestern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, where settlements and grave cultures emerged by the late 2nd millennium BCE, with more defined archaeological evidence from the Gandhara Grave Culture around the 8th–6th centuries BCE.[23] This culture, characterized by burial practices and pottery, extended into Bajaur and adjacent valleys like Swat, reflecting early Iron Age communities influenced by interactions with Central Asian nomads and local agrarian societies.[23] The area's strategic position along trade routes facilitated cultural exchanges, evidenced by grey ware ceramics and iron tools unearthed in regional excavations.[24] By the mid-6th century BCE, Gandhara, including Bajaur, fell under Achaemenid Persian control as part of the satrapy of Gandara, paying tribute in the form of troops and resources as documented in Persian inscriptions like those of Darius I.[23] Alexander the Great campaigned through Gandhara in 326 BCE, subduing local rulers near the Indus but not directly penetrating Bajaur's hilly terrain, though Hellenistic influences later permeated via successor states.[24] Under the Mauryan Empire (circa 322–185 BCE), Emperor Ashoka's edicts promoted Buddhism, leading to the construction of stupas and viharas across Gandhara; remnants of such structures in Bajaur indicate monastic activity by the 3rd century BCE.[24] The Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, and Parthian kingdoms vied for dominance in the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE, with Bajaur yielding coins and relics like the Bajaur casket (dated circa 5–6 CE), inscribed in Kharoshthi and linking Scythian Apraca rulers such as Indravarman to Buddhist patronage.[25] The Kushan Empire (1st–3rd centuries CE) marked Gandhara's artistic zenith, blending Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian styles in Buddhist sculpture; Bajaur's proximity to Taxila and Peshawar Valley sites suggests similar devotional practices, including relic veneration.[24] Post-Kushan, Hephthalite and Turk Shahi incursions disrupted the region by the 5th–7th centuries CE, eroding centralized Buddhist networks before Arab Muslim expansions from the 7th century onward.[24]Islamic and Mughal Era

The advent of Islamic rule in Bajaur occurred during the Ghaznavid Empire's expansions in the 11th century, as Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni's raids into the northwestern frontier regions introduced Muslim governance and cultural influence to peripheral areas like Bajaur, which lay along invasion routes toward Gandhara and beyond.[6] Subsequent Ghurid dynasties, succeeding the Ghaznavids after 1186, extended control over these frontier territories, incorporating Bajaur into networks of Muslim sultanates that emphasized Sunni orthodoxy and administrative integration.[26] By the late 15th century, the Yusufzai Pashtun tribe, adhering to Sunni Islam, migrated into Bajaur from eastern Afghanistan, displacing indigenous groups such as the Dilazak Pashtuns and Gabari Swatis; historical accounts indicate this settlement had occurred approximately a century prior to 1519, solidifying Yusufzai dominance in the rugged terrain.[27] The Mughal Empire's involvement commenced with Zahir-ud-din Muhammad Babur's campaign in early January 1519, when his forces assaulted Bajaur's strongholds, overrunning them in roughly 45–66 minutes and executing a mass slaughter of over 3,000 Gabari tribesmen, whom Babur characterized in his memoirs as nominal Muslims practicing pagan rituals including idol worship and refusal of circumcision.[28] Following this, Babur crossed into Swat to confront the Yusufzai, but secured a brief peace treaty, including his marriage on January 30, 1519, to Bibi Mubarika, daughter of Yusufzai leader Shah Mansur, highlighting tactical alliances amid ongoing tribal hostilities.[27] Under Akbar, Mughal efforts intensified from late 1585 through 1586 and beyond, with Zain Khan Koka leading expeditions into Bajaur and Swat to subdue Yusufzai resistance, surprising key leaders like Jalaluddin and forcing temporary submissions from various chiefs; these operations, spanning 1587–1592, involved repeated forays but yielded no permanent control, as Yusufzai guerrilla tactics and terrain advantages thwarted full pacification.[29] Mughal chronicles document dozens of forts constructed and garrisons established, yet persistent revolts underscored the limits of imperial authority in this tribal frontier.[30]British Colonial Period and Independence

During the British colonial era, Bajaur was incorporated into the tribal frontier regions of the North-West Frontier Province, established in 1901, where direct administration was limited in favor of indirect control through local tribal structures.[1] The Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) of 1901 formed the basis of governance, allowing British political officers to delegate judicial and punitive powers to tribal jirgas while imposing collective tribal responsibility for cross-border raids and internal disorders.[1] This system preserved significant autonomy for Pashtun tribes such as the Tarkanri and Utman Khel, with British influence exerted via subsidies to maliks (tribal leaders) and the deployment of irregular frontier forces to secure passes and deter Afghan encroachments.[12] British oversight in Bajaur focused on strategic imperatives, including the protection of supply routes to Chitral, where the Khan of Nawagai received allowances in exchange for maintaining order and facilitating transit.[11] Military expeditions were launched periodically to suppress tribal resistance, such as raids by Akhund of Swat's followers in the late 19th century, but permanent garrisons were avoided to minimize administrative costs and tribal alienation.[12] The region's isolation from settled districts persisted, with development limited to basic infrastructure like frontier posts, reflecting a policy of containment rather than integration. Upon the partition of British India on August 14, 1947, Bajaur's tribal leaders aligned with the new Dominion of Pakistan, entering into informal agreements that extended the pre-independence administrative framework without formal accession instruments akin to those of princely states.[31] This arrangement positioned Bajaur within the precursor to the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), under the supervisory authority of the North-West Frontier Province's political agents, who continued enforcing the FCR.[1] The transition maintained tribal self-governance while subordinating foreign affairs and defense to Pakistani control, averting immediate Afghan claims until later border disputes in the 1960s.[11]Integration into Pakistan and FATA Status

Following the partition of British India on August 14, 1947, the tribal areas adjoining the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), including Bajaur, acceded to the newly independent Dominion of Pakistan through decisions by local tribal jirgas and leaders who opted to align with the Muslim-majority state rather than India.[32] This accession was facilitated by historical ties to the Muslim League and opposition to potential Hindu-majority rule in India, with tribal representatives meeting Muhammad Ali Jinnah to pledge loyalty, though formal instruments of accession were not signed as in princely states but affirmed via agreements and assurances of autonomy. Bajaur's integration occurred amid broader Pashtun tribal deliberations, where leaders from areas like Bajaur rejected Afghan irredentist claims under the Durand Line and accepted Pakistani suzerainty in exchange for subsidies, non-interference in internal affairs, and retention of customary governance.[31] Pakistan inherited the British colonial administrative framework for these tribal regions, designating them as Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) under direct federal control, separate from provincial jurisdiction.[33] Bajaur was initially administered as a subdivision of the Malakand Agency, with its Nawab, Abdul Subhan Khan of Khar, representing the area in the NWFP Assembly, reflecting a transitional status blending tribal autonomy with Pakistani oversight.[31] It was upgraded to full agency status on December 1, 1973, becoming one of FATA's seven agencies alongside Mohmand, Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, and the Waziristans, administered by a federally appointed political agent under the Governor of NWFP (later Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).[34] Governance relied on the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR) of 1901, which empowered agents to impose collective tribal punishments, bypass regular courts, and limit individual rights, while maliks (tribal elders) mediated disputes and received allowances, preserving jirga-based justice over formal Pakistani law.[33] Under FATA status, Bajaur's residents lacked full constitutional protections, with no direct representation in Pakistan's National Assembly until the 1997 extension of adult franchise and partial adult suffrage in 1948 elections, though political parties remained banned until 2011 and the FCR persisted, enabling arbitrary executive authority that critics argued perpetuated underdevelopment and isolation.[35] This semi-autonomous arrangement maintained tribal structures but subordinated them to federal directives, including military oversight, subsidies totaling millions of rupees annually, and restrictions on infrastructure development to avoid encroachments on tribal lands.[36] The status reflected Pakistan's strategic prioritization of border security over integration, inheriting British buffer policies against Afghanistan while navigating internal tribal resistance to centralization.[34]Post-2001 Militancy Onset

Following the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, Bajaur Agency saw a significant influx of Taliban fighters, Al-Qaeda operatives, and foreign militants crossing the porous Durand Line border, particularly into areas adjacent to Afghanistan's Kunar and Nuristan provinces, where the agency served as a logistical staging ground for cross-border raids against coalition forces.[37] This migration was driven by the collapse of Taliban rule in Afghanistan and Pakistan's initial cooperation with U.S. demands to dismantle militant safe havens, which alienated local tribes harboring sympathies for the ousted regime.[38] Local networks amplified this dynamic through the Tehrik-e-Nifazi Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM), founded by Maulana Sufi Muhammad, which mobilized around 10,000 Pashtun tribesmen from Bajaur and neighboring regions to join the fight in Afghanistan under the banner of defensive jihad against non-Muslim forces.[37] TNSM's emphasis on strict Sharia enforcement resonated in Bajaur's conservative tribal society, where pre-existing anti-modernization sentiments—rooted in the agency's semi-autonomous status under the Frontier Crimes Regulation—provided fertile ground for radicalization. Concurrently, dozens of madrassas in Bajaur, many funded by Arab donors promoting Wahhabi interpretations of Islam, indoctrinated youth and served as recruitment hubs for jihadist groups including Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HuJI) and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).[37] By 2004, these elements coalesced under local commanders, with Maulvi Faqir Muhammad rising as a key figure after aligning initially with TNSM; he consolidated control over militant factions in Bajaur, forging ties to the nascent Pakistani Taliban movement and later becoming deputy emir of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) upon its formalization in December 2007.[39] Faqir Muhammad's group exploited tribal divisions, such as feuds between the dominant Uttmanzai and smaller subtribes, to expand influence, while foreign fighters—estimated in the hundreds, including Uzbeks and Arabs—provided training in IED construction and guerrilla tactics.[37] This period marked the shift from passive sanctuary provision to active Talibanization, characterized by the imposition of parallel courts, bans on music and television, and beheadings of alleged spies, as militants tested Pakistani resolve amid the army's restraint in FATA to avoid broader tribal backlash.[38] The onset escalated into overt confrontation by mid-decade, as militants, emboldened by safe passage for anti-Afghan operations, began low-level attacks on Pakistani security outposts—such as ambushes on convoys in remote tehsils—viewing the state's post-9/11 alignment with the U.S. as apostasy.[8] This insurgency's roots lay in causal factors including geographic vulnerability, historical Pakistani tolerance of Afghan mujahideen during the 1980s Soviet war (which seeded enduring networks), and the agency's undergoverned terrain, where state presence was limited to political agents and levies ill-equipped for asymmetric threats. By 2006, suicide bombings and coordinated assaults had become routine, presaging large-scale military responses like the 2008 Operation Sherdil.[38]Militancy and Security

Rise of Jihadist Groups

The influx of Afghan Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters into Bajaur Agency following the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 marked the initial phase of jihadist entrenchment, as these foreign militants exploited local Pashtunwali codes of hospitality and tribal autonomy to establish sanctuaries near the border. Local Deobandi madrasas, such as those in Damadola and Khar, served as recruitment hubs, radicalizing youth amid resentment toward Pakistan's perceived alliance with the U.S. and drone strikes, which began in 2006 and targeted high-value figures like Ayman al-Zawahiri allegedly hosted by emerging leaders.[40][41] By 2003, Pakistani military operations against al-Qaeda remnants provoked defensive jihadist responses, fostering the rise of local commanders who transitioned from supporting cross-border insurgency to challenging state authority. Maulvi Faqir Muhammad, a Mohmand tribesman and former Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM) member who had attempted to reinforce the Taliban in 2001, emerged as a pivotal figure, aligning with Baitullah Mehsud's network through beheadings of security personnel and ambushes starting around 2004–2005. Other groups, including Jaish-e-Islam under Qari Wali Rahman and Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HuJI) elements led by Qari Saifullah Akhtar, consolidated in tribal strongholds like Mamond and Charmang, often allying with Uzbek factions such as the Islamic Jihad Union for training and funding.[40] The formation of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in December 2007 unified these disparate Bajaur-based jihadists under a centralized command, with Faqir Muhammad serving as deputy emir and overseeing operations that included suicide bombings, such as the October 2008 Wali Bagh attack, and enforcement of strict Sharia in controlled areas. Qari Zia Rahman, an Afghan commander trained in Arab camps and linked to Osama bin Laden, further bolstered TTP capabilities by directing raids into Afghanistan's Kunar and Nuristan provinces while fortifying defenses against Pakistani incursions. This consolidation enabled jihadists to dominate swathes of Bajaur by mid-2008, displacing tribal elders and imposing taxes, until disrupted by Operation Sherdil in August 2008, which killed over 1,800 militants but highlighted their prior territorial gains.[40][41]Key Militant Activities and Attacks

Bajaur District has been a hotspot for jihadist militant operations, particularly by factions of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and affiliates like Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), involving suicide bombings, improvised explosive device (IED) attacks, ambushes on security convoys, and targeted assassinations of tribal elders opposing militancy. These activities escalated after 2007, with militants under local commanders such as Maulvi Faqir Muhammad establishing parallel sharia enforcement, including public executions and destruction of infrastructure deemed un-Islamic, before Pakistani military offensives disrupted their control in 2009. Attacks often exploited the district's rugged terrain and proximity to Afghanistan for cross-border staging, targeting Pakistani security forces, political rallies, and civilians to undermine state authority and enforce ideological dominance.[42]| Date | Location | Description | Casualties | Attributed Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 4, 2012 | Khar Bazaar | Suicide bomber detonated explosives in a crowded market near a security checkpoint, marking the first major TTP attack in Bajaur since late 2010. | 25 killed, over 60 injured (mostly civilians) | TTP[43] |

| July 30, 2023 | Khar | Woman suicide bomber targeted a Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam Fazl (JUI-F) political rally, exploiting crowds during election campaigning; one of the deadliest post-2018 attacks in the district. | 54 killed, over 100 injured | ISKP (claimed responsibility)[44][45] |

| April 20, 2024 | Salarzai area | Roadside IED struck a police patrol vehicle, part of a surge in low-signature attacks amid TTP resurgence. | 1 police officer killed, several injured | TTP (suspected)[46] |

Pakistani Military Responses and Operations

In response to the growing dominance of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) factions in Bajaur Agency by mid-2008, the Pakistani military launched coordinated offensives combining regular army units, Frontier Corps paramilitaries, and local tribal militias. An initial intensive campaign began in August 2008 under Frontier Corps auspices, leveraging support from the Salarzai tribe's lashkar (armed militia) led by Malik Zeb Salarzai to patrol contested areas and target foreign fighters. Tactics emphasized isolating militants through evacuation of civilian populations from strongholds, followed by artillery barrages, aerial strikes from helicopter gunships and fixed-wing aircraft, and ground assaults on training camps and hideouts; militants were given ultimatums to surrender or face destruction of their properties. This approach yielded early gains in severing militant-population ties but triggered a massive displacement of over 400,000 residents, many fleeing to adjacent Dir District or across the Afghan border.[38] Operation Sher Dil (Lion Heart), formally initiated on September 9, 2008, and extending into 2009, marked the most extensive effort to reclaim Bajaur, focusing on clearing militant-held population centers and arterial routes like Loe Sam, Khar, and Nawagai. Commanded by XI Corps under General Hussain, it deployed a brigade headquarters, four infantry battalions, one armored squadron, the Bajaur Scouts, and seven Frontier Corps wings, augmented by U.S.-provided intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets. By December 2008, official tallies reported over 1,000 militants killed—many affiliated with TTP commander Maulvi Faqir Muhammad—and the neutralization of key command nodes, at the cost of 63 Pakistani security personnel; air and ground operations disrupted supply lines and demolished dozens of fortified positions. The campaign incorporated tribal lashkars for area security, reflecting an adaptation toward hybrid counterinsurgency integrating local forces.[8] Military claims culminated in February 2009 with assertions of regaining control over 95% of Bajaur, forcing surviving militants to retreat into Afghanistan's Kunar Province or underground networks. Success metrics included the destruction of 80% of identified militant infrastructure and a temporary 70% drop in attacks, per army assessments, though independent corroboration of casualty figures remains constrained by access limitations in the region. Challenges persisted, including tactical overreliance on firepower that razed villages and alienated tribes through collective punishment perceptions, undermining governance follow-through; by 2010, partial militant re-infiltration underscored gaps in holding strategies despite infrastructure rehabilitation pledges. These operations informed subsequent FATA-wide efforts like Rah-e-Rast in Swat but highlighted the need for sustained non-kinetic measures amid cross-border sanctuary issues.[8][38]Recent Developments (2018–2025)

Following the 2018 merger of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Bajaur District saw administrative integration aimed at enhancing governance and security through extended provincial policing and judicial systems, though implementation faced delays and uneven results, with reports of persistent militant infiltration from across the Afghan border.[49][50] Security operations continued sporadically, but Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and affiliated groups exploited governance gaps, leading to a noted uptick in attacks on security forces, tribal elders, and religious scholars by 2024.[48][51] Militant violence escalated in 2025, with a suicide bombing in Khar on July 6 killing five and injuring 17, attributed to TTP-linked militants targeting a mosque gathering.[52] This prompted Pakistani security forces to launch Operation Sarbakaf on July 29, a targeted counterterrorism offensive in tehsils like Loe Mamund, imposing curfews under Section 144 and displacing over 55,000 residents while converting schools into shelters for thousands.[53][54][55] Subsequent raids in August killed at least 30 militants, including in a backfired plot involving an IED-laden mosque, and cleared four villages by mid-September, though ambushes on forces resulted in two soldiers killed and 19 injured on August 12.[56][57][58] By late 2025, operations had neutralized dozens of militants and improved local support for security measures, with chief officials claiming strengthened police presence reduced threats, yet analysts noted ongoing TTP challenges tied to cross-border sanctuaries and post-merger administrative strains.[59][60][61] The district's security remained volatile, with September incidents including a killed terrorist planting an IED, underscoring persistent risks despite military gains.[62]Impacts on Civilians and Controversies

Militant activities in Bajaur District have resulted in significant civilian casualties through targeted attacks, suicide bombings, and enforcement of strict Islamist edicts, including public executions and restrictions on women's mobility. Between 2007 and 2009, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) factions in Bajaur conducted beheadings of alleged spies and opponents, bombed girls' schools, and imposed taxes on locals, leading to an estimated hundreds of civilian deaths amid the insurgency's peak.[63] Pakistani military operations, such as those in 2008-2009 and the more recent Operation Sarbakaf launched on July 29, 2025, have inflicted collateral damage, including airstrikes and ground assaults that killed non-combatants alongside militants.[7] Reports from human rights organizations document instances of arbitrary detentions, torture, and extrajudicial killings by security forces during sweeps in Bajaur, often without due process, exacerbating local distrust.[63][64] Mass displacement has been a recurring impact, with military offensives forcing tens of thousands from their homes. In August 2025, Operation Sarbakaf prompted heavy outflows from areas like Lowi Mamund tehsil, as families fled crossfire and curfews, straining resources in host communities.[65][66] Earlier operations in the late 2000s displaced over 500,000 from Bajaur and adjacent agencies, with return hindered by ongoing violence and destroyed infrastructure.[63] Economic fallout includes razed agricultural lands, disrupted trade routes to Afghanistan, and halted education, as militants destroyed over 100 schools in Bajaur by 2010, while military actions damaged homes and markets.[67] Controversies surround both militant atrocities and state responses, with accusations of disproportionate force by the Pakistani Army drawing protests and calls for investigations. In August 2025, residents in Bajaur demonstrated against unannounced operations and curfews that allegedly caused civilian deaths, including women and children, amid reports of indiscriminate shelling.[68] Opposition figures and locals blamed security forces for 24 deaths, including non-fighters, in September 2025 blasts, though officials attributed them to militants; independent probes remain absent, fueling claims of impunity.[69] Militants' human rights violations, such as forced recruitment and summary executions, receive less international scrutiny compared to state actions, per analyses of media focus, yet both sides' abuses have perpetuated cycles of radicalization and underdevelopment in the district.[63][64]Administrative Divisions

Tehsils and Subdivisions

Bajaur District is administratively organized into two sub-divisions: Khar Sub-Division and Nawagai Sub-Division, which collectively encompass eight tehsils.[1] Khar Sub-Division consists of three tehsils: Khar Tehsil, the most populous in the district; Salarzai Tehsil, located along the border with Afghanistan; and Barang Tehsil.[2][70] Nawagai Sub-Division includes five tehsils: Loe Mamund Tehsil, Wara Mamund Tehsil, Nawagai Tehsil, Bar Chamer Kand Tehsil (also known as Chamarkand), and Utman Khel Tehsil, with most bordering Afghanistan.[71][4]Local Governance Structure

The local governance in Bajaur District operates under the framework of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Government Act, 2013, as amended in 2019 to encompass former FATA areas post the 25th Constitutional Amendment merger in 2018. This establishes decentralized tiers including village and neighbourhood councils for grassroots functions, tehsil councils for broader municipal oversight, and district-level coordination, with elected officials responsible for services like sanitation, minor infrastructure development, vital event registration, and local revenue collection.[72][73] Local government elections in 2021 facilitated the election of chairmen for village councils and tehsil nazims across Bajaur's tehsils, such as Khar, with results notifying seat allocations including reserved quotas for women, youth, peasants/workers, and minorities.[74][75] Tehsil Municipal Administrations (TMAs) form a key component, each headed by a Tehsil Municipal Officer (TMO) as the principal accounting officer, handling urban services, licensing, and maintenance; for instance, TMA services were formally launched in Khar tehsil in January 2020.[76][77] These align with the district's eight tehsils (Khar, Mamund, Nawagai, Salarzai, Barang, Lohi, Uttmanzai, and Razar), subdivided under two main administrative units at Khar and Nawagai.[1] The Deputy Commissioner (DC) heads the district administration, acting as coordinator between provincial directives and local bodies while overseeing law enforcement, development planning, and fiscal accountability.[76] Supporting the DC are one Additional Deputy Commissioner, two Assistant Commissioners (one each for Khar and Nawagai subdivisions), and eight tehsildars.[1] This bureaucratic layer integrates with elected structures but retains significant executive control, particularly in security-sensitive contexts, where tribal levies have been merged into the provincial police.[78] Implementation challenges persist, including delayed full devolution of funds and powers to elected councils, leading to by-elections in 2024 for vacant seats and critiques of the system's erosion amid fiscal constraints and militancy impacts.[79][80] As of 2024, former FATA districts like Bajaur added 25 tehsil local governments and over 700 village councils province-wide, yet effective local autonomy remains partial due to transitional gaps.[81][82]Demographics

Population Statistics

According to the 2023 Population and Housing Census conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Bajaur District recorded a total population of 1,287,960 residents.[5] This figure reflects a near-equal sex distribution, with 650,798 males reported, yielding a sex ratio of approximately 100 males per 100 females.[83] The district covers an area of 1,290 square kilometers, resulting in a population density of 998.4 persons per square kilometer as of 2023.[5] Compared to the 2017 census, which enumerated 1,093,684 inhabitants, the population increased by 194,276 over the six-year period, corresponding to an average annual growth rate of 2.8%.[5] This growth aligns with broader trends in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's former Federally Administered Tribal Areas, where high fertility rates and limited out-migration contribute to sustained expansion despite security challenges.[84] Bajaur District is overwhelmingly rural, with urban areas comprising a minimal proportion of the population—estimated at under 3.5% based on 2017 classifications that designated only select centers like Khar as urban.[16] Updated 2023 urban-rural delineations from census data maintain this predominantly rural character, reflecting the district's tribal and agrarian structure with few formalized urban settlements.[85] Household size averages around 7 persons, consistent with patterns in Pashtun tribal regions.[85]Ethnic and Tribal Composition

Bajaur District is inhabited almost exclusively by ethnic Pashtuns, who constitute the vast majority of the population, with no significant non-Pashtun communities reported in official demographic data.[1] The district's social structure revolves around Pashtun tribal affiliations, governed traditionally by kinship-based clans and sub-tribes adhering to Pashtunwali, the unwritten ethnic code emphasizing hospitality, revenge, and tribal autonomy. The two primary tribal groups are the Tarkani (also spelled Tarkanri) and Utman Khel, with the Tarkani forming the largest in terms of population and territorial influence.[1] The Tarkani tribe encompasses several sub-tribes, including the Mamund (dominant in areas like Loe Mamund and Wara Mamund tehsils), Salarzai, Tarkalanri, and smaller groups such as Wur and Kakazai, which collectively control much of the district's fertile valleys and hilly terrains. The Utman Khel, concentrated in the northern and eastern parts bordering Dir Lower, represent the second major tribe and maintain distinct lineages tracing back to broader Pashtun confederacies like the Karlani branch.[1] [86] Tribal demographics from the 2017 census highlight the Utman Khel's enumerated households at around 10,602, underscoring their sizable presence amid the district's total population of 1,093,684.[86] [1] Inter-tribal dynamics have historically influenced land disputes and alliances, particularly along the Afghan border, where cross-border kinship ties with Kunar Province's Pashtun groups amplify local loyalties over state boundaries. Minor nomadic or semi-nomadic elements, such as Gujjar herders, occasionally traverse the area but do not form settled ethnic enclaves.[87]Languages and Dialects

The predominant language in Bajaur District is Pashto, spoken natively by approximately 96.6% of the population as the primary medium of communication in daily life, education, and local governance.[3] This dominance reflects the district's ethnic Pashtun majority and its location within the Pashtun cultural heartland of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Minor languages such as Urdu (the national language of Pakistan) and others like Hindko or Saraiki are reported by small percentages, often among non-native residents or migrants, but do not exceed 1-2% in census data from specific tehsils.[88][89] Pashto in Bajaur belongs to the Northern Pashto variety, specifically the north-eastern or "hard" dialect subtype known as Pakhto, characterized by distinct phonological features such as retroflex sounds and vowel shifts compared to southern dialects like those in Kandahar.[90] This dialect aligns with usage in adjacent regions including Swat, Buner, Mohmand, and parts of eastern Afghanistan (e.g., Nangarhar and Kunar), forming a continuum of the Yusufzai-influenced northern group.[91] The local variant, often termed Bajauri Pashto, incorporates tribal-specific lexicon tied to the Utman Khel and Tarkani Pashtun subtribes predominant in the district, with influences from cross-border interactions but retaining core northern traits like aspirated consonants and ergative case marking.[92] Literacy and media in Bajaur primarily utilize this dialect, though standardized Pashto (based on the softer western form) is employed in formal writing and broadcasting, leading to some bilingual adaptation among educated residents.[93] No significant indigenous non-Pashto languages persist, as historical migrations and cultural assimilation have marginalized any pre-Pashtun substrates, such as potential Dardic elements in peripheral valleys.[94]Religion and Cultural Practices

The population of Bajaur District is overwhelmingly Muslim, with estimates indicating 100% adherence to Islam, predominantly Sunni.[95] No significant non-Muslim minorities, such as Christians or Hindus, are recorded in the district's demographics.[95] Religious life is shaped by conservative Sunni interpretations, with historical centers of Islamic learning dating back to the 7th century spread of Islam in the region.[96] Cultural practices are deeply rooted in Pashtunwali, the unwritten tribal code of the Pashtun majority, which emphasizes values like melmastia (hospitality), badal (revenge or justice), and nanawati (asylum-seeking).[6] This code integrates with Islamic principles, reinforcing community loyalty, bravery, and honor in daily interactions and dispute resolution through tribal jirgas. Traditional attire includes shalwar kameez for men paired with hand-made Dir caps, while women observe conservative dress norms aligned with religious modesty.[11] Festivals and social events highlight Pashtun hospitality, often involving communal feasts and oral poetry recitations, though insecurity has limited public celebrations in recent years.[1] Indigenous ethno-medicinal practices persist, with local communities relying on over 70 plant species for treatments, reflecting a blend of pre-Islamic herbal traditions and Islamic healing invocations.[97] Efforts to preserve these customs include government-organized symposia promoting regional languages, folklore, and traditions amid modernization pressures.[98]Governance and Politics

Political Representation

Bajaur District is represented in the National Assembly of Pakistan by a single constituency, NA-8, which covers the entire district. The current Member of the National Assembly is Mubarak Zeb Khan, an independent candidate who secured victory in the by-election held on April 22, 2024, with 74,008 votes against competitors including PTI-backed Gul Zafar Khan.[99][100] Khan, supported by Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) workers despite running independently amid party symbol restrictions, previously won the February 8, 2024, general election polls for both NA-8 and PK-22 before vacating the provincial seat.[100] In the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Bajaur contributes three seats through constituencies PK-20 (Bajaur-II), PK-21 (Bajaur-III), and PK-22 (Bajaur-IV). These were contested in the February 8, 2024, general elections, with one subsequent by-election. The current members are:| Constituency | Member | Party/Affiliation | Election Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| PK-20 Bajaur-II | Anwar Zeb Khan | Independent (PTI-backed) | February 8, 2024[101] |

| PK-21 Bajaur-III | Ajmal Khan | Independent | February 8, 2024[102] |

| PK-22 Bajaur-IV | Muhammad Nisar Khan | Awami National Party | July 12, 2024 (by-election)[103][104] |

Tribal Jirga System and State Authority