Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Radiation protection

View on WikipediaRadiation protection, also known as radiological protection, is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "The protection of people from harmful effects of exposure to ionizing radiation, and the means for achieving this".[1] Exposure can be from a source of radiation external to the human body or due to internal irradiation caused by the ingestion of radioactive contamination.

Ionizing radiation is widely used in industry and medicine, and can present a significant health hazard by causing microscopic damage to living tissue. There are two main categories of ionizing radiation health effects. At high exposures, it can cause "tissue" effects, also called "deterministic" effects due to the certainty of them happening, conventionally indicated by the unit gray and resulting in acute radiation syndrome. For low level exposures there can be statistically elevated risks of radiation-induced cancer, called "stochastic effects" due to the uncertainty of them happening, conventionally indicated by the unit sievert.

Fundamental to radiation protection is the avoidance or reduction of dose using the simple protective measures of time, distance and shielding. The duration of exposure should be limited to that necessary, the distance from the source of radiation should be maximised, and the source or the target shielded wherever possible. To measure personal dose uptake in occupational or emergency exposure, for external radiation personal dosimeters are used, and for internal dose due to ingestion of radioactive contamination, bioassay techniques are applied.

For radiation protection and dosimetry assessment the International Commission on Radiation Protection (ICRP) and International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) publish recommendations and data which is used to calculate the biological effects on the human body of certain levels of radiation, and thereby advise acceptable dose uptake limits.

Principles

[edit]

The ICRP recommends, develops and maintains the International System of Radiological Protection, based on evaluation of the large body of scientific studies available to equate risk to received dose levels. The system's health objectives are "to manage and control exposures to ionising radiation so that deterministic effects are prevented, and the risks of stochastic effects are reduced to the extent reasonably achievable".[2]

The ICRP's recommendations flow down to national and regional regulators, which have the opportunity to incorporate them into their own law; this process is shown in the accompanying block diagram. In most countries a national regulatory authority works towards ensuring a secure radiation environment in society by setting dose limitation requirements that are generally based on the recommendations of the ICRP.

Exposure situations

[edit]The ICRP recognises planned, emergency, and existing exposure situations, as described below;[3]

- Planned exposure – defined as "...where radiological protection can be planned in advance, before exposures occur, and where the magnitude and extent of the exposures can be reasonably predicted."[4] These are such as in occupational exposure situations, where it is necessary for personnel to work in a known radiation environment.

- Emergency exposure – defined as "...unexpected situations that may require urgent protective actions".[5] This would be such as an emergency nuclear event.

- Existing exposure – defined as "...being those that already exist when a decision on control has to be taken".[6] These can be such as from naturally occurring radioactive materials which exist in the environment.

Regulation of dose uptake

[edit]The ICRP uses the following overall principles for all controllable exposure situations.[7]

- Justification: No unnecessary use of radiation is permitted, which means that the advantages must outweigh the disadvantages.

- Limitation: Each individual must be protected against risks that are too great, through the application of individual radiation dose limits.

- Optimization: This process is intended for application to those situations that have been deemed to be justified. It means "the likelihood of incurring exposures, the number of people exposed, and the magnitude of their individual doses" should all be kept As Low As Reasonably Achievable (or Reasonably Practicable) known as ALARA or ALARP. It takes into account economic and societal factors.

Factors in external dose uptake

[edit]There are three factors that control the amount, or dose, of radiation received from a source. Radiation exposure can be managed by a combination of these factors:

- Time: Reducing the time of an exposure reduces the effective dose proportionally. An example of reducing radiation doses by reducing the time of exposures might be improving operator training to reduce the time they take to handle a radioactive source.

- Distance: Increasing distance reduces dose due to the inverse square law. Distance can be as simple as handling a source with forceps rather than fingers. For example, if a problem arises during fluoroscopic procedure step away from the patient if feasible.

- Shielding: Sources of radiation can be shielded with solid or liquid material, which absorbs the energy of the radiation. The term 'biological shield' is used for absorbing material placed around a nuclear reactor, or other source of radiation, to reduce the radiation to a level safe for humans. The shielding materials are concrete and lead shield which is 0.25 mm thick for secondary radiation and 0.5 mm thick for primary radiation[8]

Internal dose uptake

[edit]

Internal dose, due to the inhalation or ingestion of radioactive substances, can result in stochastic or deterministic effects, depending on the amount of radioactive material ingested and other biokinetic factors.

The risk from a low level internal source is represented by the dose quantity committed dose, which has the same risk as the same amount of external effective dose.

The intake of radioactive material can occur through four pathways:

- inhalation of airborne contaminants such as radon gas and radioactive particles

- ingestion of radioactive contamination in food or liquids

- absorption of vapours such as tritium oxide through the skin

- injection of medical radioisotopes such as technetium-99m

The occupational hazards from airborne radioactive particles in nuclear and radio-chemical applications are greatly reduced by the extensive use of gloveboxes to contain such material. To protect against breathing in radioactive particles in ambient air, respirators with particulate filters are worn.

To monitor the concentration of radioactive particles in ambient air, radioactive particulate monitoring instruments measure the concentration or presence of airborne materials.

For ingested radioactive materials in food and drink, specialist laboratory radiometric assay methods are used to measure the concentration of such materials.[9]

Recommended limits on dose uptake

[edit]

The ICRP recommends a number of limits for dose uptake in table 8 of ICRP report 103. These limits are "situational", for planned, emergency and existing situations. Within these situations, limits are given for certain exposed groups;[10]

- Planned exposure – limits given for occupational, medical and public exposure. The occupational exposure limit of effective dose is 20 mSv per year, averaged over defined periods of 5 years, with no single year exceeding 50 mSv. The public exposure limit is 1 mSv in a year.[11]

- Emergency exposure – limits given for occupational and public exposure

- Existing exposure – reference levels for all persons exposed

The public information dose chart of the USA Department of Energy, shown here on the right, applies to USA regulation, which is based on ICRP recommendations. Note that examples in lines 1 to 4 have a scale of dose rate (radiation per unit time), whilst 5 and 6 have a scale of total accumulated dose.

ALARP & ALARA

[edit]ALARP is an acronym for an important principle in exposure to radiation and other occupational health risks and in the UK stands for As Low As Reasonably Practicable.[12] The aim is to minimize the risk of radioactive exposure or other hazard while keeping in mind that some exposure may be acceptable in order to further the task at hand. The equivalent term ALARA, As Low As Reasonably Achievable, is more commonly used outside the UK.

This compromise is well illustrated in radiology. The application of radiation can aid the patient by providing doctors and other health care professionals with a medical diagnosis, but the exposure of the patient should be reasonably low enough to keep the statistical probability of cancers or sarcomas (stochastic effects) below an acceptable level, and to eliminate deterministic effects (e.g. skin reddening or cataracts). An acceptable level of incidence of stochastic effects is considered to be equal for a worker to the risk in other radiation work generally considered to be safe.

This policy is based on the principle that any amount of radiation exposure, no matter how small, can increase the chance of negative biological effects such as cancer. It is also based on the principle that the probability of the occurrence of negative effects of radiation exposure increases with cumulative lifetime dose. These ideas are combined to form the linear no-threshold model which says that there is not a threshold at which there is an increase in the rate of occurrence of stochastic effects with increasing dose. At the same time, radiology and other practices that involve use of ionizing radiation bring benefits, so reducing radiation exposure can reduce the efficacy of a medical practice. The economic cost, for example of adding a barrier against radiation, must also be considered when applying the ALARP principle. Computed tomography, better known as CT scans or CAT scans have made an enormous contribution to medicine, however not without some risk. The ionizing radiation used in CT scans can lead to radiation-induced cancer.[13] Age is a significant factor in risk associated with CT scans,[14] and in procedures involving children and systems that do not require extensive imaging, lower doses are used.[15]

Personal radiation dosimeters

[edit]The radiation dosimeter is an important personal dose measuring instrument. It is worn by the person being monitored and is used to estimate the external radiation dose deposited in the individual wearing the device. They are used for gamma, X-ray, beta and other strongly penetrating radiation, but not for weakly penetrating radiation such as alpha particles. Traditionally, film badges were used for long-term monitoring, and quartz fibre dosimeters for short-term monitoring. However, these have been mostly superseded by thermoluminescent dosimetry (TLD) badges and electronic dosimeters. Electronic dosimeters can give an alarm warning if a preset dose threshold has been reached, enabling safer working in potentially higher radiation levels, where the received dose must be continually monitored.

Workers exposed to radiation, such as radiographers, nuclear power plant workers, doctors using radiotherapy, those in laboratories using radionuclides, and HAZMAT teams are required to wear dosimeters so a record of occupational exposure can be made. Such devices are generally termed "legal dosimeters" if they have been approved for use in recording personnel dose for regulatory purposes.

Dosimeters can be worn to obtain a whole body dose and there are also specialist types that can be worn on the fingers or clipped to headgear, to measure the localised body irradiation for specific activities.

Common types of wearable dosimeters for ionizing radiation include:[16][17]

Radiation protection

[edit]

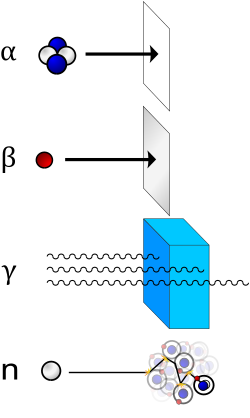

Different types of ionizing radiation interact in different ways with shielding material. Different shielding techniques are therefore used depending on the application, the type and energy of the radiation.

Shielding reduces the intensity of radiation, increasing with thickness. The dose decreases exponentially with the thickness of the shielding material. The shielding value of a material is typically indicated by a parameter called the "half-value layer", i.e. the thickness required to halve the dose, for a given radiation type (eg α, β or γ) and energy. For example, a practical shield in a fallout shelter with ten layers of packed dirt, each as thick as the material's half-value layer for that radiation, will reduce the dose to 1/1024 of its original intensity (i.e. 2−10). Almost any material may provide an adequate radiation shield if used in sufficient thickness.

The effectiveness of a shielding material in general increases with its atomic number (Z), except for neutron shielding, which is more readily shielded by the likes of neutron absorbers and moderators such as compounds of boron (e.g. boric acid), cadmium, carbon and hydrogen.

Graded-Z shielding is a laminate of several materials with different Z values (atomic numbers) designed to protect against different types of ionizing radiation. Compared to single-material shielding, the same mass of graded-Z shielding has been shown to reduce electron penetration over 60%.[18] It is commonly used in satellite-based particle detectors, offering several benefits:

- protection from radiation damage

- reduction of background noise for detectors

- lower mass compared to single-material shielding

Designs vary, but typically involve a gradient from high-Z (usually tantalum) through successively lower-Z elements such as tin, steel, and copper, usually ending with aluminium. Sometimes even lighter materials such as polypropylene or boron carbide are used.[19][20]

In a typical graded-Z shield, the high-Z layer effectively scatters protons and electrons. It also absorbs gamma rays, which produces X-ray fluorescence. Each subsequent layer absorbs the X-ray fluorescence of the previous material, eventually reducing the energy to a suitable level. Each decrease in energy produces Bremsstrahlung and Auger electrons, which are below the detector's energy threshold. Some designs also include an outer layer of aluminium, which may simply be the skin of the satellite. The effectiveness of a material as a biological shield is related to its cross-section for scattering and absorption, and to a first approximation is proportional to the total mass of material per unit area interposed along the line of sight between the radiation source and the region to be protected. Hence, shielding strength or "thickness" is conventionally measured in units of g/cm2. The radiation that manages to get through falls exponentially with the thickness of the shield. In x-ray facilities, walls surrounding the room with the x-ray generator may contain lead shielding such as lead sheets, or the plaster may contain barium sulfate. Operators view the target through a leaded glass screen, or if they must remain in the same room as the target, wear lead aprons.

Particle radiation

[edit]Particle radiation consists of a stream of charged or neutral particles, both charged ions and subatomic elementary particles. This includes solar wind, cosmic radiation, and neutron flux in nuclear reactors.

- Alpha particles (helium nuclei) are the least penetrating. Even very energetic alpha particles can be stopped by a single sheet of paper.

- Beta particles (electrons) are more penetrating, but still can be absorbed by a few millimetres of aluminium. However, in cases where high-energy beta particles are emitted, shielding must be accomplished with low atomic weight materials, e.g. plastic, wood, water, or acrylic glass (Plexiglas, Lucite).[21] This is to reduce generation of Bremsstrahlung X-rays. In the case of beta+ radiation (positrons), the gamma radiation from the electron–positron annihilation reaction poses additional concern.

- Neutron radiation is not as readily absorbed as charged particle radiation, which makes this type highly penetrating. In a process called neutron activation, neutrons are absorbed by nuclei of atoms in a nuclear reaction. This most often creates a secondary radiation hazard, as the absorbing nuclei transmute to the next-heavier isotope, many of which are unstable.

- Cosmic radiation is not a common concern on Earth, as the Earth's atmosphere absorbs it and the magnetosphere acts as a shield, but it poses a significant problem for satellites and astronauts, especially while passing through the Van Allen Belt or while completely outside the protective regions of the Earth's magnetosphere. Frequent fliers may be at a slightly higher risk because of the decreased absorption from thinner atmosphere. Cosmic radiation is extremely high energy, and is very penetrating.

Electromagnetic radiation

[edit]Electromagnetic radiation consists of emissions of electromagnetic waves, the properties of which depend on the wavelength.

- X-ray and gamma radiation are best absorbed by atoms with heavy nuclei; the heavier the nucleus, the better the absorption. In some special applications, depleted uranium or thorium[22] are used, but lead is much more common; several cm are often required. Barium sulfate is used in some applications too. However, when the cost is important, almost any material can be used, but it must be far thicker. Most nuclear reactors use thick concrete shields to create a bioshield with a thin water-cooled layer of lead on the inside to protect the porous concrete from the coolant inside. The concrete is also made with heavy aggregates, such as Baryte or Magnetite, to aid in the shielding properties of the concrete. Gamma rays are better absorbed by materials with high atomic numbers and high density, although neither effect is important compared to the total mass per area in the path of the gamma ray.

- Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is ionizing in its shortest wavelengths but is not penetrating, so it can be shielded by thin opaque layers such as sunscreen, clothing, and protective eyewear. Protection from UV is simpler than for the other forms of radiation above, so it is often considered separately.

In some cases, improper shielding can actually make the situation worse, when the radiation interacts with the shielding material and creates secondary radiation that absorbs in the organisms more readily. For example, although high atomic number materials are very effective in shielding photons, using them to shield beta particles may cause higher radiation exposure due to the production of Bremsstrahlung x-rays, and hence low atomic number materials are recommended. Also, using a material with a high neutron activation cross section to shield neutrons will result in the shielding material itself becoming radioactive and hence more dangerous than if it were not present.

Personal protective equipment

[edit]Personal protective equipment (PPE) includes all clothing and accessories which can be worn to prevent severe illness and injury as a result of exposure to radioactive material. These include an SR100 (protection for 1hr), SR200 (protection for 2 hours). Because radiation can affect humans through internal and external contamination, various protection strategies have been developed to protect humans from the harmful effects of radiation exposure from a spectrum of sources.[23] A few of these strategies developed to shield from internal, external, and high energy radiation are outlined below.

Internal contamination protective equipment

[edit]Internal contamination protection equipment protects against the inhalation and ingestion of radioactive material. Internal deposition of radioactive material result in direct exposure of radiation to organs and tissues inside the body. The respiratory protective equipment described below are designed to minimize the possibility of such material being inhaled or ingested as emergency workers are exposed to potentially radioactive environments.

Reusable air purifying respirators (APR)

- Elastic face piece worn over the mouth and nose

- Contains filters, cartridges, and canisters to provide increased protection and better filtration

Powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR)

- Battery powered blower forces contamination through air purifying filters

- Purified air delivered under positive pressure to face piece

Supplied-air respirator (SAR)

- Compressed air delivered from a stationary source to the face piece

Auxiliary escape respirator

- Protects wearer from breathing harmful gases, vapours, fumes, and dust

- Can be designed as an air-purifying escape respirator (APER) or a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) type respirator

- SCBA type escape respirators have an attached source of breathing air and a hood that provides a barrier against contaminated outside air

Self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA)

- Provides very pure, dry compressed air to full facepiece mask via a hose

- Air is exhaled to environment

- Worn when entering environments immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH) or when information is inadequate to rule out IDLH atmosphere

External contamination protective equipment

[edit]External contamination protection equipment provides a barrier to shield radioactive material from being deposited externally on the body or clothes. The dermal protective equipment described below acts as a barrier to block radioactive material from physically touching the skin, but does not protect against externally penetrating high energy radiation.

Chemical-resistant inner suit

- Porous overall suit—Dermal protection from aerosols, dry particles, and non hazardous liquids.

- Non-porous overall suit to provide dermal protection from:

- Dry powders and solids

- Blood-borne pathogens and bio-hazards

- Chemical splashes and inorganic acid/base aerosols

- Mild liquid chemical splashes from toxics and corrosives

- Toxic industrial chemicals and materials

Level C equivalent: Bunker gear

- Firefighter protective clothing

- Flame/water resistant

- Helmet, gloves, foot gear, and hood

Level B equivalent: Non-gas-tight encapsulating suit

- Designed for environments that are immediate health risks but contain no substances that can be absorbed by skin

Level A equivalent: Totally encapsulating chemical- and vapour-protective suit

- Designed for environments that are immediate health risks and contain substances that can be absorbed by skin

External penetrating radiation

[edit]There are many solutions to shielding against low-energy radiation exposure like low-energy X-rays. Lead shielding wear such as lead aprons can protect patients and clinicians from the potentially harmful radiation effects of day-to-day medical examinations. It is quite feasible to protect large surface areas of the body from radiation in the lower-energy spectrum because very little shielding material is required to provide the necessary protection. Recent studies show that copper shielding is far more effective than lead and is likely to replace it as the standard material for radiation shielding.[citation needed]

Personal shielding against more energetic radiation such as gamma radiation is very difficult to achieve as the large mass of shielding material required to properly protect the entire body would make functional movement nearly impossible. For this, partial body shielding of radio-sensitive internal organs is the most viable protection strategy.

The immediate danger of intense exposure to high-energy gamma radiation is acute radiation syndrome (ARS), a result of irreversible bone marrow damage. The concept of selective shielding is based in the regenerative potential of the hematopoietic stem cells found in bone marrow. The regenerative quality of stem cells make it only necessary to protect enough bone marrow to repopulate the body with unaffected stem cells after the exposure: a similar concept which is applied in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), which is a common treatment for patients with leukemia. This scientific advancement allows for the development of a new class of relatively lightweight protective equipment that shields high concentrations of bone marrow to defer the hematopoietic sub-syndrome of acute radiation syndrome to much higher dosages.

One technique is to apply selective shielding to protect the high concentration of bone marrow stored in the hips and other radio-sensitive organs in the abdominal area. This allows first responders a safe way to perform necessary missions in radioactive environments.[24]

Radiation protection instruments

[edit]Practical radiation measurement using calibrated radiation protection instruments is essential in evaluating the effectiveness of protection measures, and in assessing the radiation dose likely to be received by individuals. The measuring instruments for radiation protection are both "installed" (in a fixed position) and portable (hand-held or transportable).

Installed instruments

[edit]Installed instruments are fixed in positions which are known to be important in assessing the general radiation hazard in an area. Examples are installed "area" radiation monitors, Gamma interlock monitors, personnel exit monitors, and airborne particulate monitors.

The area radiation monitor will measure the ambient radiation, usually X-Ray, Gamma or neutrons; these are radiations that can have significant radiation levels over a range in excess of tens of metres from their source, and thereby cover a wide area.

Gamma radiation "interlock monitors" are used in applications to prevent inadvertent exposure of workers to an excess dose by preventing personnel access to an area when a high radiation level is present. These interlock the process access directly.

Airborne contamination monitors measure the concentration of radioactive particles in the ambient air to guard against radioactive particles being ingested, or deposited in the lungs of personnel. These instruments will normally give a local alarm, but are often connected to an integrated safety system so that areas of plant can be evacuated and personnel are prevented from entering an air of high airborne contamination.

Personnel exit monitors (PEM) are used to monitor workers who are exiting a "contamination controlled" or potentially contaminated area. These can be in the form of hand monitors, clothing frisk probes, or whole body monitors. These monitor the surface of the workers body and clothing to check if any radioactive contamination has been deposited. These generally measure alpha or beta or gamma, or combinations of these.

The UK National Physical Laboratory publishes a good practice guide through its Ionising Radiation Metrology Forum concerning the provision of such equipment and the methodology of calculating the alarm levels to be used.[25]

Portable instruments

[edit]

Portable instruments are hand-held or transportable. The hand-held instrument is generally used as a survey meter to check an object or person in detail, or assess an area where no installed instrumentation exists. They can also be used for personnel exit monitoring or personnel contamination checks in the field. These generally measure alpha, beta or gamma, or combinations of these.

Transportable instruments are generally instruments that would have been permanently installed, but are temporarily placed in an area to provide continuous monitoring where it is likely there will be a hazard. Such instruments are often installed on trolleys to allow easy deployment, and are associated with temporary operational situations.

In the United Kingdom the HSE has issued a user guidance note on selecting the correct radiation measurement instrument for the application concerned.[26] This covers all radiation instrument technologies, and is a useful comparative guide.

Instrument types

[edit]A number of commonly used detection instrument types are listed below, and are used for both fixed and survey monitoring.

Radiation related quantities

[edit]The following table shows the main radiation-related quantities and units.

| Quantity | Unit | Symbol | Derivation | Year | SI equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (A) | becquerel | Bq | s−1 | 1974 | SI unit |

| curie | Ci | 3.7×1010 s−1 | 1953 | 3.7×1010 Bq | |

| rutherford | Rd | 106 s−1 | 1946 | 1000000 Bq | |

| Exposure (X) | coulomb per kilogram | C/kg | C⋅kg−1 of air | 1974 | SI unit |

| röntgen | R | esu / 0.001293 g of air | 1928 | 2.58×10−4 C/kg | |

| Absorbed dose (D) | gray | Gy | J⋅kg−1 | 1974 | SI unit |

| erg per gram | erg/g | erg⋅g−1 | 1950 | 1.0×10−4 Gy | |

| rad | rad | 100 erg⋅g−1 | 1953 | 0.010 Gy | |

| Equivalent dose (H) | sievert | Sv | J⋅kg−1 × WR | 1977 | SI unit |

| röntgen equivalent man | rem | 100 erg⋅g−1 × WR | 1971 | 0.010 Sv | |

| Effective dose (E) | sievert | Sv | J⋅kg−1 × WR × WT | 1977 | SI unit |

| röntgen equivalent man | rem | 100 erg⋅g−1 × WR × WT | 1971 | 0.010 Sv |

Spacecraft radiation challenges

[edit]Spacecraft, both robotic and crewed, must cope with the high radiation environment of outer space. Radiation emitted by the Sun and other galactic sources, and trapped in radiation "belts" is more dangerous and hundreds of times more intense than radiation sources such as medical X-rays or normal cosmic radiation usually experienced on Earth.[28] When the intensely ionizing particles found in space strike human tissue, it can result in cell damage and may eventually lead to cancer.

The usual method for radiation protection is material shielding by spacecraft and equipment structures (usually aluminium), possibly augmented by polyethylene in human spaceflight where the main concern is high-energy protons and cosmic ray ions. On uncrewed spacecraft in high-electron-dose environments such as Jupiter missions, or medium Earth orbit (MEO), additional shielding with materials of a high atomic number can be effective. On long-duration crewed missions, advantage can be taken of the good shielding characteristics of liquid hydrogen fuel and water.

The NASA Space Radiation Laboratory makes use of a particle accelerator that produces beams of protons or heavy ions. These ions are typical of those accelerated in cosmic sources and by the Sun. The beams of ions move through a 100 m (328-foot) transport tunnel to the 37 m2 (400-square-foot) shielded target hall. There, they hit the target, which may be a biological sample or shielding material.[28] In a 2002 NASA study, it was determined that materials that have high hydrogen contents, such as polyethylene, can reduce primary and secondary radiation to a greater extent than metals, such as aluminum.[29] The problem with this "passive shielding" method is that radiation interactions in the material generate secondary radiation.

Active Shielding, that is, using magnets, high voltages, or artificial magnetospheres to slow down or deflect radiation, has been considered to potentially combat radiation in a feasible way. So far, the cost of equipment, power and weight of active shielding equipment outweigh their benefits. For example, active radiation equipment would need a habitable volume size to house it, and magnetic and electrostatic configurations often are not homogeneous in intensity, allowing high-energy particles to penetrate the magnetic and electric fields from low-intensity parts, like cusps in dipolar magnetic field of Earth. As of 2012, NASA is undergoing research in superconducting magnetic architecture for potential active shielding applications.[30]

Early radiation dangers

[edit]

The dangers of radioactivity and radiation were not immediately recognized. The discovery of x‑rays in 1895 led to widespread experimentation by scientists, physicians, and inventors. Many people began recounting stories of burns, hair loss and worse in technical journals as early as 1896. In February of that year, Professor Daniel and Dr. Dudley of Vanderbilt University performed an experiment involving x-raying Dudley's head that resulted in his hair loss. A report by Dr. H.D. Hawks, a graduate of Columbia College, of his severe hand and chest burns in an x-ray demonstration, was the first of many other reports in Electrical Review.[31]

Many experimenters including Elihu Thomson at Thomas Edison's lab, William J. Morton, and Nikola Tesla also reported burns. Elihu Thomson deliberately exposed a finger to an x-ray tube over a period of time and experienced pain, swelling, and blistering.[32] Other effects, including ultraviolet rays and ozone were sometimes blamed for the damage.[33] Many physicists claimed that there were no effects from x-ray exposure at all.[32]

As early as 1902 William Herbert Rollins wrote almost despairingly that his warnings about the dangers involved in careless use of x-rays was not being heeded, either by industry or by his colleagues. By this time Rollins had proved that x-rays could kill experimental animals, could cause a pregnant guinea pig to abort, and that they could kill a fetus.[34] [self-published source?] He also stressed that "animals vary in susceptibility to the external action of X-light" and warned that these differences be considered when patients were treated by means of x-rays.

Before the biological effects of radiation were known, many physicists and corporations began marketing radioactive substances as patent medicine in the form of glow-in-the-dark pigments. Examples were radium enema treatments, and radium-containing waters to be drunk as tonics. Marie Curie protested against this sort of treatment, warning that the effects of radiation on the human body were not well understood. Curie later died from aplastic anaemia, likely caused by exposure to ionizing radiation. By the 1930s, after a number of cases of bone necrosis and death of radium treatment enthusiasts, radium-containing medicinal products had been largely removed from the market (radioactive quackery).

See also

[edit]- CBLB502, 'Protectan', a radioprotectant drug under development for its ability to protect cells during radiotherapy.

- Ex-Rad, a United States Department of Defense radioprotectant drug under development.

- Health physics

- Health threat from cosmic rays

- International Radiation Protection Association – (IRPA). The International body concerned with promoting the science and practice of radiation protection.

- Juno Radiation Vault

- Non-ionizing radiation

- Nuclear safety

- Potassium iodide

- Radiation monitoring

- Radiation Protection Convention, 1960

- Radiation protection reports of the European Union

- Radiobiology

- Radiological protection of patients

- Radioresistance

- Society for Radiological Protection – The principal UK body concerned with promoting the science and practice of radiation protection. It is the UK national affiliated body to IRPA

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation

References

[edit]- ^ IAEA Safety Glossary - draft 2016 revision.

- ^ ICRP. Report 103. pp. para 29.

- ^ ICRP. "Report 103": Section 6.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ ICRP. "Report 103": para 253.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ ICRP. "Report 103": para 274.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ ICRP. "Report 103": para 284.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ ICRP. "Report 103": Introduction.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Biological shield". United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Venturi Sebastiano (2022). "Prevention of nuclear damage caused by iodine and cesium radionuclides to the thyroid, pancreas and other organs". Juvenis Scientia. 8 (2): 5–14. doi:10.32415/jscientia_2022_8_2_5-14. S2CID 250392484.

- ^ ICRP. "Report 103": Table 8, section 6.5.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ ICRP, International Commission on Radiological Protection. "Dose limits". ICRPedia. ICRP. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ This is the wording used by the national regulatory authority that coined the term, in turn derived from its enabling legislation: Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974: "Risk management: ALARP at a glance". London: Health and Safety Executive. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

'ALARP' is short for 'as low as reasonably practicable'

- ^ Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (November 2007). "Computed tomography – an increasing source of radiation exposure" (PDF). N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (22): 2277–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072149. PMID 18046031. S2CID 2760372. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Whaites, Eric (2008-10-10). Radiography and Radiology for Dental Care Professionals E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7020-4799-2.

- ^ Semelka RC, Armao DM, Elias J, Huda W (May 2007). "Imaging strategies to reduce the risk of radiation in CT studies, including selective substitution with MRI". J Magn Reson Imaging. 25 (5): 900–9. doi:10.1002/jmri.20895. PMID 17457809. S2CID 5788891.

- ^ Advances in kilovoltage x-ray beam dosimetry by Hill et al in http://iopscience.iop.org/0031-9155/59/6/R183/article

- ^ Seco, Joao; Clasie, Ben; Partridge, Mike (Oct 2014). "Review on the characteristics of radiation detectors for dosimetry and imaging". Physics in Medicine and Biology. 59 (20): R303 – R347. Bibcode:2014PMB....59R.303S. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/59/20/R303. PMID 25229250. S2CID 4393848.

- ^ Fan, W.C.; et al. (1996). "Shielding considerations for satellite microelectronics". IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 43 (6): 2790–2796. Bibcode:1996ITNS...43.2790F. doi:10.1109/23.556868.

- ^ Smith, D.M.; et al. (2002). "The RHESSI Spectrometer". Solar Physics. 210 (1): 33–60. Bibcode:2002SoPh..210...33S. doi:10.1023/A:1022400716414. S2CID 122624882.

- ^ Pia, Maria Grazia; et al. (2009). "PIXE Simulation with Geant4". IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 56 (6): 3614–3649. Bibcode:2009ITNS...56.3614P. doi:10.1109/TNS.2009.2033993. S2CID 41649806.

- ^ "No Such Site | U-M WP Hosting" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-20. Retrieved 2005-12-15.

- ^ Historical Use of Thorium at Hanford Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in a Radiation Emergency - Radiation Emergency Medical Management". www.remm.nlm.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-06-21. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ "Occupational Radiation Protection in Severe Accident Management" (PDF). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA).

- ^ Operational Monitoring Good Practice Guide "The Selection of Alarm Levels for Personnel Exit Monitors" Dec 2009 - National Physical Laboratory, Teddington UK [1]

- ^ [2] Archived 2018-07-30 at the Wayback Machine Selection, use and maintenance of portable monitoring instruments. UK HSE

- ^ "Measuring Radiation". NRC Web. Archived from the original on 2025-05-16. Retrieved 2025-10-06.

- ^ a b "Behind the scenes - NASA's Space Radiation Laboratory". NASA. 2003. Archived from the original on 2004-10-30. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ^ "Understanding Space Radiation" (PDF). Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. NASA. October 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-30. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

FS-2002-10-080-JSC

- ^ "Radiation Protection and Architecture Utilizing High Temperature Superconducting Magnets". NASA Johnson Space Center. Shayne Westover. 2012. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ^ Sansare, K.; Khanna, V.; Karjodkar, F. (2011). "Early victims of X-rays: a tribute and current perception". Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. 40 (2): 123–125. doi:10.1259/dmfr/73488299. ISSN 0250-832X. PMC 3520298. PMID 21239576.

- ^ a b "Ronald L. Kathern and Paul L. Ziemer, he First Fifty Years of Radiation Protection, physics.isu.edu". Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2014-10-06.

- ^ Hrabak, M.; Padovan, R. S.; Kralik, M.; Ozretic, D.; Potocki, K. (July 2008). "Nikola Tesla and the Discovery of X-rays". RadioGraphics. 28 (4): 1189–92. doi:10.1148/rg.284075206. PMID 18635636.

- ^ Geoff Meggitt (2008), Taming the Rays - A history of Radiation and Protection., Lulu.com, ISBN 978-1-4092-4667-1 [self-published source]

Notes

[edit]- Harvard University Radiation Protection Office Providing radiation guidance to Harvard University and affiliated institutions.

- Journal of Solid State Phenomena Tara Ahmadi, Use of Semi-Dipole Magnetic Field for Spacecraft Radiation Protection.

External links

[edit]- [3] - "The confusing world of radiation dosimetry" - M.A. Boyd, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. An account of chronological differences between USA and ICRP dosimetry systems.

- "Halving-thickness for various materials". The Compass DeRose Guide to Emergency Preparedness - Hardened Shelters. Archived from the original on 2018-01-22. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

Radiation protection

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Radiation and Its Effects

Types of Ionizing Radiation

Ionizing radiation encompasses subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves capable of ionizing atoms by ejecting electrons, thereby producing ion pairs in matter.[10] The primary types relevant to radiation protection are alpha particles, beta particles, gamma rays, X-rays, and neutrons, each characterized by distinct physical properties affecting their interaction with matter, penetration depth, and biological impact.[11] These differences dictate specific shielding strategies and exposure risks, with particulate radiations (alpha, beta, neutrons) differing from electromagnetic ones (gamma, X-rays) in mass and charge.[12] Alpha particles consist of helium nuclei (two protons and two neutrons), possessing a +2 charge and relatively high mass (approximately 4 atomic mass units).[13] Emitted during the alpha decay of heavy radionuclides like uranium-238 or radium-226, they exhibit low penetration, traveling only a few centimeters in air and being stopped by a sheet of paper or the outer layer of dead skin.[10] Consequently, alpha radiation poses minimal external hazard but is highly damaging if inhaled or ingested due to dense ionization tracks causing severe local tissue destruction.[14] Beta particles are high-speed electrons (negatrons) or positrons emitted from nuclei during beta decay, as seen in isotopes like carbon-14 or strontium-90.[11] With negligible mass and a -1 or +1 charge, they penetrate farther than alpha particles—up to several meters in air—but are attenuated by approximately 1 cm of plastic, aluminum sheeting, or heavy clothing.[10] Beta emitters present both external skin burn risks and internal hazards via contamination, with energy-dependent ranges varying from low-energy (e.g., tritium, stopped by skin) to high-energy forms requiring denser shielding.[15] Gamma rays and X-rays are high-energy photons without mass or charge, produced by nuclear transitions (gamma from excited nuclei like cobalt-60) or electron shell rearrangements (X-rays from accelerating charges in tubes or brakes).[14] Indistinguishable in interaction mechanisms—Compton scattering, photoelectric effect, and pair production—they exhibit high penetrability, requiring several inches of lead or feet of concrete for effective shielding.[10] Their uncharged nature allows deep tissue penetration, necessitating distance, time limits, and dense barriers in protection protocols; gamma rays typically exceed X-ray energies but overlap in medical and industrial applications.[11] Neutrons, uncharged particles with mass similar to protons, arise primarily from fission reactions in nuclear reactors or spontaneous sources like californium-252.[12] Lacking charge, they penetrate deeply—moderated only by hydrogen-rich materials like water, polyethylene, or concrete that slow them via elastic collisions—before capture gamma emission adds secondary hazards.[16] Neutron radiation induces activation in materials, creating secondary emitters, and delivers high biological effectiveness through dense ionization patterns, demanding specialized moderation and shielding in nuclear facilities.[15]| Type | Charge | Mass (relative) | Typical Range in Air | Primary Shielding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | +2 | High (~4 u) | Few cm | Paper, skin |

| Beta | ±1 | Negligible | Meters | Plastic, aluminum |

| Gamma/X-ray | 0 | None | Kilometers | Lead, concrete |

| Neutron | 0 | ~1 u | Deep penetration | Water, paraffin |

Biological Mechanisms of Damage

Ionizing radiation interacts with biological tissues primarily through energy deposition via ionization and excitation of atoms, leading to the formation of ion pairs and free radicals that disrupt molecular structures.[17] This process targets water molecules, which constitute about 70-80% of cellular mass, initiating radiolysis that produces reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), hydrated electrons (e⁻_{aq}), and hydrogen radicals (•H).[18] These reactive oxygen species (ROS) account for approximately 60-70% of DNA damage in oxygenated cells, with the remainder resulting from direct ionization of biomolecules.[19] Damage occurs via two principal pathways: direct effects, where radiation energy ionizes DNA or other critical molecules, causing immediate bond breaks, and indirect effects mediated by diffusible radicals from water radiolysis that abstract hydrogen atoms or add to bases, yielding adducts and strand breaks.[18] Direct ionization predominantly generates clustered damage in DNA, including double-strand breaks (DSBs) within 10 base pairs, which are inefficiently repaired and highly mutagenic.[20] Indirect effects amplify damage through ROS-induced oxidation of DNA bases (e.g., 8-oxoguanine) and sugars, with hydroxyl radicals reacting at diffusion-limited rates of about 10^9-10^10 M⁻¹s⁻¹.[17] Low-linear energy transfer (LET) radiations like X- or γ-rays produce sparse ionizations favoring indirect damage, while high-LET particles (e.g., α-particles) cause dense tracks with predominantly direct, complex lesions.[19] At the cellular level, DNA lesions trigger the DNA damage response (DDR), involving sensors like ATM and ATR kinases that phosphorylate H2AX histone variant, forming γ-H2AX foci to recruit repair factors.[21] Repair mechanisms include base excision repair (BER) for oxidized or alkylated bases via enzymes like OGG1, nucleotide excision repair (NER) for bulky distortions, and DSB repair via homologous recombination (HR) in S/G2 phases or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) throughout the cell cycle, with NHEJ prone to error-prone ligations yielding deletions or translocations.[22] Unrepaired or misrepaired DSBs, occurring at yields of 20-40 per gray for low-LET radiation, lead to chromosomal aberrations such as dicentrics or acentric fragments, detectable via fluorescence in situ hybridization.[23] Beyond DNA, radiation oxidizes proteins (e.g., carbonylation of amino acids) and peroxidizes membrane lipids, impairing enzymatic function and signaling, though these contribute less to lethality than genomic instability.[17] Oxygen enhances damage by converting initial radicals into persistent ROS (oxygen fixation), increasing effective yield by a factor of 2-3 via the oxygen enhancement ratio (OER).[24] Persistent genomic instability manifests as delayed mutations or bystander effects in non-irradiated cells via gap junction signaling or secreted factors, amplifying population-level risks.[25]Dose-Response Models

Dose-response models in radiation biology quantify the relationship between ionizing radiation dose and adverse health effects, particularly stochastic outcomes such as cancer induction. These models underpin radiological protection standards by extrapolating risks from high-dose observations to lower, environmentally relevant exposures. For deterministic effects like tissue damage, a clear threshold exists below which no harm occurs due to cellular repair capacity exceeding damage; however, stochastic effects are modeled differently, with debates centering on whether risks are proportional to dose without a safe level or mitigated at low exposures.[26] The linear no-threshold (LNT) model posits that cancer risk increases linearly with dose, assuming every increment of radiation carries proportional risk regardless of magnitude, with no repairable threshold. Originating from atomic bomb survivor data analyzed in the 1950s and formalized in reports like BEIR VII (2006), LNT serves as the basis for international dose limits, such as the 1 mSv annual public exposure cap recommended by the ICRP. This conservative approach prioritizes precaution but has faced criticism for overestimating low-dose risks (<100 mSv), as epidemiological studies of nuclear workers and high-background radiation populations show no elevated cancer rates or even reduced incidences compared to unexposed groups. For instance, a 2015 U.S. NRC review of petitions highlighted mounting evidence that LNT inflates carcinogenesis risks at low doses, potentially fostering radiophobia and unnecessary regulatory burdens.[27][28][29] Alternative models challenge LNT's universality. The threshold model asserts a dose below which stochastic risks are negligible, supported by observations that DNA repair mechanisms handle low-level damage effectively, as seen in animal studies and human cohorts exposed to chronic low doses. Radiation hormesis proposes a biphasic response: low doses (<100 mSv) stimulate adaptive protective mechanisms, such as enhanced DNA repair and antioxidant production, yielding net health benefits like reduced cancer mortality, while high doses cause harm. Evidence includes a meta-analysis of nuclear industry workers showing 20-50% lower solid cancer rates at cumulative doses up to 200 mSv, and ecological studies in high-natural-background areas like Kerala, India, reporting lower cancer prevalence. UNSCEAR's 2010 report on low-dose effects acknowledged uncertainties in LNT extrapolations but noted insufficient data to reject it outright, though subsequent reviews, including a 2024 medRxiv preprint surveying five low-dose response types (LNT, threshold, supralinearity, linearity with threshold, hormesis), underscore empirical support for non-linear behaviors.[30][31][32] The persistence of LNT in policy, despite these critiques, reflects a precautionary stance amid scientific disagreement, with bodies like the NRC in 2021 citing lack of consensus to maintain status quo limits. Critics argue this prioritizes economic and political factors over causal evidence, as low-dose exposures (e.g., medical imaging at 10-50 mSv) show no detectable health detriment in large cohorts, per UNSCEAR's ongoing evaluations of biological mechanisms. Resolution requires refined epidemiology and mechanistic studies, but current data favor models incorporating thresholds or hormesis for doses below 100 mSv to align protection with observed causality rather than unverified linearity.[33][34][9]Core Principles of Protection

Justification, Optimization, and Dose Limitation

The three fundamental principles of radiological protection—justification, optimization, and dose limitation—form the cornerstone of the system recommended by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) in its Publication 103, published in 2007, and endorsed by international bodies such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).[35][1] These principles apply primarily to planned exposure situations, such as nuclear power operations or medical diagnostics, where radiation use is deliberate and controllable, ensuring that exposures are managed to maximize societal benefits while minimizing risks.[36] They emphasize a risk-benefit framework grounded in empirical dose-response data, acknowledging that ionizing radiation carries stochastic risks (e.g., cancer induction) proportional to dose at low levels, though absolute risks remain small compared to natural background exposures of approximately 2-3 mSv per year globally.[36][3] Justification requires that any practice or action altering radiation exposure—whether introducing a new radiation source or modifying an existing one—must yield net benefits exceeding potential harms, evaluated through quantitative risk assessments and qualitative societal considerations.[36] For planned practices, this entails regulatory approval prior to implementation, ensuring alternatives without radiation (e.g., non-ionizing imaging in medicine) are infeasible or inferior; for example, computed tomography scans are justified only when diagnostic yield justifies the incremental cancer risk, estimated at 5-10 per 10,000 exposures for a 10 mSv dose based on linear no-threshold (LNT) modeling derived from atomic bomb survivor data.[1][37] In existing exposure situations, such as naturally occurring radon in homes, justification applies to interventions like ventilation, where reduction in lung cancer risk (approximately 16% attributable to radon per WHO estimates) must outweigh costs.[3] Failure to justify can lead to unnecessary exposures, as evidenced by overuse of diagnostic imaging contributing to up to 2% of cancers in high-income countries per some epidemiological studies.[37] Optimization, often implemented via the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) or ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) concept, mandates that radiation doses and exposure probabilities be restricted to levels that provide adequate protection, balanced against economic and societal factors, using tools like cost-benefit analysis.[36] This principle applies across all exposure situations, prioritizing gross optimization for the group followed by individual dose constraints; for instance, in nuclear facilities, shielding and procedural refinements have reduced worker doses from averages exceeding 20 mSv annually in the 1950s to below 1 mSv today in many operations, reflecting iterative improvements informed by dosimetry feedback.[35][38] In medical contexts, optimization involves diagnostic reference levels (DRLs), such as IAEA-recommended CT head scan doses under 2 mSv, adjusted via protocol audits to avoid overexposure without compromising image quality.[1] Constraints are set below dose limits, e.g., 0.3 mSv/year for public exposures near facilities, ensuring disproportionate burdens are avoided.[39] Dose limitation establishes upper bounds on individual effective doses from planned exposures to prevent deterministic effects (e.g., tissue damage above 100 mSv acute) and constrain stochastic risks, with ICRP recommending 20 mSv per year averaged over five consecutive years for radiation workers (not exceeding 50 mSv in any single year) and 1 mSv per year for the public, excluding medical and background sources.[40] These limits derive from LNT extrapolations calibrated to high-dose epidemiological data, such as the Life Span Study of Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors showing excess relative risk of 0.05-0.1 per Sv for solid cancers.[35] Limits do not apply to patients in diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, where optimization suffices to avoid exceeding necessary doses, as imposing limits could deny beneficial treatments like radiotherapy delivering 50-70 Gy localized.[41] Compliance is monitored via personal dosimeters and regulatory enforcement, with exceedances triggering investigations; for example, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission data indicate worker doses remain well below limits, averaging 0.6 mSv in 2022.[3] Dose limits complement but do not supplant justification and optimization, as limits alone cannot ensure minimal exposures.[40]ALARA/ALARP Implementation

The ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principle, formalized by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in the 1970s, mandates that licensees make every reasonable effort to maintain radiation exposures below dose limits, considering economic and social factors, through a structured optimization process.[42] In parallel, the ALARP (As Low As Reasonably Practicable) concept, emphasized in UK regulations such as the Ionising Radiations Regulations 2017 (IRR17), requires restricting exposures to levels where further reductions would be grossly disproportionate in cost or effort relative to benefits, integrating risk assessment and tolerability criteria.[43][44] Both principles operationalize the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) optimization requirement, prioritizing feasible dose minimization without compromising operational necessity, and are implemented via radiation protection programs that include planning, monitoring, and iterative review. Implementation begins with program establishment, where facilities develop documented procedures, such as NRC-mandated radiation protection programs scaled to activity scope, incorporating ALARA objectives through management commitment, staff training, and resource allocation.[45][46] Key operational strategies draw from fundamental controls: minimizing exposure time, maximizing distance from sources (inverse square law reduction), and deploying shielding materials tailored to radiation type (e.g., lead for gamma rays).[16] Engineering solutions, like automated handling systems or fixed barriers, are prioritized over administrative measures to embed ALARA/ALARP inherently in design phases, followed by procedural safeguards such as job-specific Radiation Work Permits (RWPs) that outline dose goals, hazards, and controls before work commences.[47] For targeted dose reduction, an ALARA/ALARP analysis process is applied, particularly for high-risk tasks:- Problem identification: Assess baseline exposures via dosimetry data, contamination surveys, and historical records to pinpoint contributors.

- Option generation: Brainstorm alternatives, including procedural tweaks (e.g., remote tools), shielding enhancements, or work sequencing, excluding infeasible or cost-prohibitive ideas.[48]

- Evaluation: Quantify projected dose savings against implementation costs using cost-benefit ratios (e.g., dollars per person-Sv averted), with ALARP incorporating a "gross disproportion factor" typically 1:2 to 1:10 for tolerability.[44]

- Decision and implementation: Select the option yielding optimal protection, document rationale, and integrate via pre-job briefings, real-time monitoring with operational dosimeters, and post-job audits.[47]

Exposure Categories

Radiation exposure in the context of radiological protection is classified into three primary categories: occupational, public, and medical. These distinctions, established by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), enable tailored application of protection principles such as justification, optimization, and dose limitation, accounting for differences in voluntariness, controllability, and risk-benefit profiles.[52][53] Occupational exposure pertains to workers handling radiation sources or materials in professional settings, where higher dose limits are permitted due to informed consent and monitoring. Public exposure encompasses the general population, excluding occupational and medical scenarios, with stricter limits to ensure negligible risk from practices or natural sources. Medical exposure involves patients undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, prioritizing clinical benefit over strict dose caps but requiring rigorous justification.[52][37] Occupational Exposure refers to radiation doses received by individuals whose work involves potential exposure, such as nuclear industry workers, medical radiologists, or industrial radiographers. The ICRP recommends an effective dose limit of 20 millisieverts (mSv) per year, averaged over five consecutive years with no single year exceeding 50 mSv, to prevent stochastic effects while allowing for operational necessities.[54] This category excludes exposures from medical procedures or background radiation, focusing instead on controllable workplace sources like X-rays, gamma emitters, or radionuclides. Protection emphasizes personal dosimetry, training, and engineering controls, with regulatory bodies like the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission enforcing monitoring to ensure compliance below deterministic thresholds, such as 100 mSv for skin exposure to avoid erythema.[55] Global data indicate average occupational doses remain low; for instance, in the European Union, monitored workers averaged 1.1 mSv in 2019, far below limits, reflecting effective implementation.[56] Public Exposure applies to any member of the general population, including visitors to controlled areas but excluding workers and patients. The ICRP sets a principal limit of 1 mSv per year for planned exposure from artificial sources, designed to keep lifetime risks comparable to natural background levels of approximately 2.4 mSv annually worldwide.[52] This category covers releases from nuclear facilities, consumer products like smoke detectors containing americium-241, or air travel cosmic rays, but excludes unavoidable natural exposures unless enhanced (e.g., radon in homes). In emergency situations, such as the 1986 Chernobyl accident, public doses varied widely, with evacuees receiving up to 30 mSv, prompting optimized countermeasures like relocation.[57] Regulations mandate environmental monitoring and public information to maintain exposures as low as reasonably achievable, with higher temporary limits permissible in existing exposure situations like high natural radioactivity areas in Kerala, India, where doses reach 10-20 mSv/year without evident excess cancer rates in cohort studies.[58] Medical Exposure denotes doses to patients from diagnostic imaging (e.g., CT scans averaging 7-10 mSv per procedure) or radiotherapy (up to 50-70 Gy localized for tumors), where no numerical dose limits apply due to the overriding diagnostic or therapeutic intent.[3] The ICRP mandates justification—ensuring individual benefit outweighs detriment—and optimization via diagnostic reference levels, such as 20 mSv for complex CT exams in adults.[52] This category also includes exposures to carers of treated patients or volunteers in research, limited to 1 mSv/year or 5 mSv over five years, respectively. Globally, medical exposures constitute the largest artificial source, contributing about 1.8 mSv per capita annually in developed nations by 2020, driven by increased imaging; however, unwarranted procedures inflate collective doses without proportional benefits, underscoring the need for evidence-based referral criteria.[41] Incidental exposures to medical staff are treated as occupational, while patient doses demand post-procedure audits to minimize risks like radiation-induced cataracts at thresholds around 0.5-2 Gy.[37]Radiation Dosimetry and Quantities

Key Dose Metrics

The primary dose metrics in radiation protection are absorbed dose, equivalent dose, and effective dose, which quantify the physical energy deposition, biological effectiveness of radiation types, and overall stochastic health risks, respectively, as established by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP).[59] These quantities enable the assessment of exposures for regulatory limits and optimization principles.[60] Absorbed dose (D) is defined as the mean energy imparted by ionizing radiation per unit mass of irradiated material, with the SI unit of gray (Gy), equivalent to 1 joule per kilogram (J/kg).[61] It measures the fundamental physical interaction regardless of radiation type or biological effects, applicable to both deterministic and stochastic outcomes.[62] The older unit, rad, equals 0.01 Gy and was historically used before the adoption of SI units in 1975.[60] Equivalent dose (H_T) extends absorbed dose by incorporating the relative biological effectiveness through multiplication by radiation weighting factors (w_R), which vary by radiation type—such as 1 for photons and electrons, 20 for protons and alpha particles—yielding units of sievert (Sv).[61] This metric addresses variations in damage potential from sparse versus dense ionization tracks, focusing on tissue-specific stochastic risks.[59] One Sv equals 100 rem, the legacy unit.[60] Effective dose (E) sums equivalent doses across organs weighted by tissue weighting factors (w_T), reflecting differential cancer induction risks—for instance, 0.12 for lungs and 0.04 for bone surface—providing a whole-body risk proxy in Sv.[61] Intended for protection against stochastic effects in optimized scenarios, it cannot be measured directly but is estimated via operational quantities like personal dose equivalent.[63] For internal exposures, committed effective dose integrates projected doses over 50 years post-intake.[59]| Dose Quantity | Definition | Unit (SI) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbed dose | Energy per unit mass | Gy (J/kg) | Physical dosimetry, acute effects threshold |

| Equivalent dose | Absorbed dose × w_R | Sv | Radiation-type adjusted tissue dose |

| Effective dose | Σ (equivalent dose × w_T) | Sv | Stochastic risk assessment, limits |

Measurement Techniques

Personal dosimeters are essential for monitoring individual exposure in radiation protection, typically worn on the body to estimate shallow or deep dose equivalent. Common types include thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLDs), which use materials like lithium fluoride that store energy from ionizing radiation and release it as light upon heating, proportional to the absorbed dose; these are processed in laboratories post-exposure for accurate readout.[16] Optically stimulated luminescence dosimeters (OSLDs) operate similarly but use stimulation by light instead of heat, offering reusability and sensitivity to low doses down to 1 mGy, with calibration traceable to standards for quantities like Hp(10) ambient dose equivalent.[3] Electronic personal dosimeters provide real-time digital displays of cumulative dose and dose rate, often incorporating ionization chambers or solid-state detectors, and can alarm at preset thresholds such as 1 mSv per quarter for occupational limits.[16][64] For area and environmental monitoring, ionization chambers measure exposure rates in roentgens per hour or air kerma, suitable for gamma and X-ray fields above 0.1 mR/h, as they quantify ion pairs produced in a gas-filled cavity under high voltage without saturation.[65][66] Geiger-Mueller (GM) counters detect beta, gamma, and sometimes alpha radiation by counting ionization events that trigger avalanches in a gas tube, providing count rates (e.g., counts per minute) convertible to dose rates via calibration factors specific to source energy, though they saturate in high fields and do not directly measure dose.[67] Scintillation detectors, using crystals like sodium iodide that emit light flashes proportional to energy deposited, offer higher efficiency for gamma spectroscopy and dose estimation, with pulse-height analysis enabling discrimination of radionuclides.[68] In vivo dosimetry verifies delivered doses during procedures like radiotherapy by placing detectors (e.g., diodes or MOSFETs) directly on or in the patient, measuring entrance or exit doses to ensure agreement within 5% of planned values, thus supporting protection against unintended exposures.[69] Internal dosimetry for incorporated radionuclides relies on bioassay techniques, such as whole-body counting of gamma emitters or urinary excretion analysis for alpha/beta emitters, modeled via ICRP biokinetic data to estimate committed effective dose.[70] All techniques require traceability to primary standards, like those from NIST or BIPM, using cesium-137 sources for calibration, ensuring accuracy within 5-10% for protection monitoring.[71]External Radiation Protection Methods

Fundamental Strategies: Time, Distance, Shielding

The three cardinal strategies for mitigating external ionizing radiation exposure—minimizing exposure time, maximizing distance from the source, and interposing shielding—stem from the inverse proportionality of dose to protective measures and the physics of radiation attenuation. These principles apply primarily to penetrating radiations like gamma rays and x-rays, though adaptations exist for charged particles. Dose reduction via time leverages the linear accumulation of energy deposition, while distance exploits geometric dilution, and shielding relies on probabilistic interactions such as photoelectric absorption, Compton scattering, and pair production.[72][73][74] Minimizing time of exposure directly reduces the cumulative absorbed dose, as dose equals the product of dose rate and exposure duration; halving time halves the dose from a constant field. This strategy is implemented by limiting occupancy in high-radiation zones, employing automated or remote operations, and rotating personnel to distribute exposure. For example, in nuclear facilities, workers use countdown timers and procedural limits to ensure tasks near sources last seconds rather than minutes, preventing doses from exceeding regulatory thresholds like the 50 millisieverts annual occupational limit recommended by the International Commission on Radiological Protection in 2007.[75][76][73] Maximizing distance capitalizes on the inverse square law for isotropic point sources, whereby radiation intensity at distance follows ; doubling quarters the intensity and thus the dose rate, assuming negligible attenuation in air. This holds for gamma emitters like cobalt-60, where moving from 1 meter to 2 meters reduces exposure from, say, 1 roentgen per hour to 0.25 roentgens per hour. Practical applications include extending tool handles or using robotics in radiography and reactor maintenance, though for extended sources like beams, the benefit diminishes beyond certain ranges due to non-point geometry.[73][77] Shielding attenuates radiation flux through absorption or scattering in intervening matter, with efficacy governed by the material's atomic number , density, and the radiation's energy; the half-value layer (HVL)—the thickness halving intensity—quantifies this, e.g., 1.2 cm of lead for 100 keV photons. Alpha particles, with ranges under 5 cm in air, are shielded by paper or skin; beta particles (electrons up to ~MeV energies) by 1-10 mm of low-Z plastics like acrylic to minimize bremsstrahlung; gamma rays demand high-Z, high-density barriers such as 5-10 cm lead or meters-thick concrete for sources like cesium-137. Neutron shielding additionally requires hydrogenous materials like water or polyethylene to moderate via elastic scattering before capture. Selection balances attenuation against secondary radiation production and weight constraints.[78][76][75] Common shielding materials are selected based on their densities and elemental compositions, which influence attenuation efficiency for specific radiation types. High-density, high-Z elements excel for gamma photons via photoelectric and pair production processes, while hydrogen-rich compounds moderate neutrons effectively.| Material | Density (g/cm³) | Elemental Composition (weight fraction) |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 1.00 | H: 0.1119, O: 0.8881 |

| Lead | 11.34 | Pb: 1.0 |

| Tungsten | 19.25 | W: 1.0 |

| Depleted Uranium | 19.05 | U: 1.0 |

| Paraffin Wax | 0.93 | C: 0.85, H: 0.15 |

| Polyethylene | 0.94 | C: 0.857, H: 0.143 |

| High-Density Polyethylene | 0.96 | C: 0.857, H: 0.143 |

| Geopolymer Concrete (approx.) | 2.2 | O: 0.50, Si: 0.28, Al: 0.12, Ca: 0.05, Na: 0.03, Fe: 0.02 |

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE) for radiation protection consists of garments and accessories that provide localized shielding against external ionizing radiation, primarily photons (X-rays and gamma rays) and beta particles, by attenuating their penetration into the body. These items are deployed in occupational settings such as medical fluoroscopy, nuclear power plants, and radiography laboratories to reduce dose to non-critical areas while allowing access for tasks. Unlike time or distance strategies, PPE offers portable, body-conforming barriers but requires regular inspection for defects like cracks, which can compromise integrity and lead to uneven protection.[79][80] Lead-impregnated aprons, typically 0.25 to 0.5 mm thick in lead equivalence, form the cornerstone of PPE, attenuating 75-99% of scattered radiation in the diagnostic X-ray range (50-150 kVp), with 0.5 mm equivalents blocking over 90% at common energies. Thyroid shields, gloves, and leaded eyeglasses complement aprons by protecting sensitive organs; for instance, 0.5 mm lead-equivalent glasses reduce lens dose from scatter by similar margins, mitigating cataract risks documented in interventional radiology workers. In higher-energy gamma environments, such as those involving cobalt-60 sources (1.17-1.33 MeV), thicker or composite materials are needed, as standard 0.5 mm lead halves intensity only 2-3 times due to the half-value layer (HVL) exceeding 1 cm for lead at these energies.[81][82][83] Modern alternatives to pure lead include lead-free composites incorporating high atomic number elements like bismuth, antimony, or tungsten embedded in polymers, offering comparable attenuation at reduced weight—up to 30-40% lighter for equivalent protection against diagnostic photons—while minimizing toxicity risks from lead degradation. These materials maintain HVL properties akin to lead for low-to-medium energy photons but may underperform against neutrons or very high-energy gamma without additives like boron. Effectiveness varies with radiation energy and angle; oblique incidence improves attenuation, but PPE cannot shield against neutrons effectively without hydrogen-rich layers for moderation.[84][85][86]| Material Type | Typical Thickness (mm Pb eq.) | Attenuation Example (Scatter X-rays, ~80 kVp) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Vinyl | 0.25-0.5 | 75-99% | High density, proven efficacy |

| Bismuth Composite | 0.25-0.5 | 80-95% | Lighter, non-toxic |

| Tungsten Alloy | 0.35-0.5 | 85-98% | Durable, flexible |

Internal Radiation Protection Methods

Contamination Prevention and Decontamination

Contamination prevention strategies in occupational radiation environments emphasize engineering and administrative controls to minimize the release and dispersion of radioactive particulates, thereby reducing the risk of internal uptake via inhalation or ingestion. Engineering measures include the deployment of containment systems such as glove boxes, fume hoods with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration, and sealed process enclosures to capture aerosols and prevent airborne spread during handling of unsealed sources.[91] Administrative protocols enforce zoning of workspaces into uncontaminated and potentially contaminated areas, mandate pre- and post-task surveys using portable alpha/beta scintillation detectors, and require procedural safeguards like minimizing open handling and using disposable tools to avoid transfer pathways.[92] These approaches, grounded in regulatory frameworks, have demonstrably reduced incident rates in nuclear facilities by limiting source term releases.[93] Decontamination of personnel focuses on prompt external removal to avert internal contamination, as skin-associated radionuclides can migrate via hand-to-mouth contact or absorption through minor wounds. The primary step involves doffing outer clothing in a controlled manner, which removes up to 90% of loose surface contamination without generating airborne dust.[94] This is immediately followed by showering with copious amounts of lukewarm water and mild soap, applied gently to avoid driving particles into pores—hot water risks dilation and deeper penetration, while cold water may constrict pores and trap residues.[95][96] For persistent hotspots, such as nails or hair, additional rinsing with chelating agents like DTPA may be employed under medical supervision if alpha-emitters are suspected, though efficacy varies by isotope solubility.[97] Surface and equipment decontamination employs a hierarchy of techniques tailored to contamination fixity and radionuclide chemistry, prioritizing removable fractions to facilitate reuse and waste minimization. Dry methods, including HEPA-vacuuming or absorbent wiping with materials like cheesecloth or strippable coatings, effectively capture 70-95% of labile particulates without generating secondary waste streams.[98] For adherent contamination, wet techniques such as detergent scrubbing or acid/alkaline solutions (e.g., citric acid for oxides) dissolve and rinse away fixed layers, achieving reductions to release limits below 0.04 Bq/cm² for beta/gamma emitters in many cases.[99] Mechanical abrasion or electrochemical methods serve as escalatory options for robust surfaces like metals, with post-decon verification via smear tests ensuring residual levels comply with clearance criteria, such as those specified in IAEA safety standards.[99] Success metrics emphasize radiological surveys confirming dose rate reductions and smearable contamination below actionable thresholds, preventing re-aerosolization during operations.[100]Respiratory and Ingestion Controls