Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A feud /fjuːd/, also known in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, private war, or mob war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially families or clans. Feuds begin because one party perceives itself to have been attacked, insulted, injured, or otherwise wronged by another. Intense feelings of resentment trigger an initial retribution, which causes the other party to feel greatly aggrieved and vengeful. The dispute is subsequently fueled by a long-running cycle of retaliatory violence. This continual cycle of provocation and retaliation usually makes it extremely difficult to end the feud peacefully. Feuds can persist for generations and may result in extreme acts of violence. They can be interpreted as an extreme outgrowth of social relations based in family honor. A mob war is a time when two or more rival families begin open warfare with one another, destroying each other's businesses and assassinating family members. Mob wars are generally disastrous for all concerned, and can lead to the rise or fall of a family.

Until the early modern period, feuds were considered legitimate legal instruments[1] and were regulated to some degree. For example, Montenegrin culture calls this krvna osveta, meaning "blood revenge", which had unspoken[dubious – discuss] but highly valued rules.[2] In Albanian culture it is called gjakmarrja, which usually lasts for generations. In tribal societies, the blood feud, coupled with the practice of blood wealth, functioned as an effective form of social control for limiting and ending conflicts between individuals and groups who are related by kinship, as described by anthropologist Max Gluckman in his article "The Peace in the Feud"[3] in 1955.

Blood feuds

[edit]A blood feud is a feud with a cycle of retaliatory violence, with the relatives or associates of someone who has been killed or otherwise wronged or dishonored seeking vengeance by killing or otherwise physically punishing the culprits or their relatives. In the English-speaking world, the Italian word vendetta is used to mean a blood feud; in Italian, however, it simply means (personal) 'vengeance' or 'revenge', originating from the Latin vindicta (vengeance), while the word faida would be more appropriate for a blood feud. In the English-speaking world, "vendetta" is sometimes extended to mean any other long-standing feud, not necessarily involving bloodshed. Sometimes it is not mutual, but rather refers to a prolonged series of hostile acts waged by one person against another without reciprocation.[4]

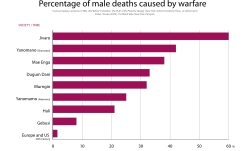

The blood feud has certain similarities to the ritualized warfare found in many pre-industrial tribes. For instance, more than a third of Ya̧nomamö males, on average, died from warfare. The accounts of missionaries to the area have recounted constant infighting in the tribes for women or prestige, and evidence of continuous warfare for the enslavement of neighboring tribes, such as the Macu, before the arrival of European settlers and government.[5]

History

[edit]Blood feuds were common in societies with a weak rule of law (or where the state did not consider itself responsible for mediating this kind of dispute), where family and kinship ties were the main source of authority. An entire family was considered responsible for the actions of any of its members. Sometimes two separate branches of the same family even came to blows, or further, over some dispute.

The practice has mostly disappeared with more centralized societies where law enforcement and criminal law take responsibility for punishing lawbreakers.

Feuds in Antiquity

[edit]Ancient Greece

[edit]In Homeric ancient Greece, the practice of personal vengeance against wrongdoers was considered natural and customary: "Embedded in the Greek morality of retaliation is the right of vengeance... Feud is a war, just as war is an indefinite series of revenges; and such acts of vengeance are sanctioned by the gods".[6]

Hebrew Law

[edit]In ancient Hebrew law, it was considered the duty of the individual and family to avenge unlawful bloodshed, on behalf of God and on behalf of the deceased. The executor of the law of blood-revenge who personally put the initial killer to death was given a special designation: go'el haddam, the blood-avenger or blood-redeemer (Book of Numbers 35: 19, etc.). Six Cities of Refuge were established to provide protection and due process for any unintentional manslayers. The avenger was forbidden from harming an unintentional killer if the killer took refuge in one of these cities. As the Oxford Companion to the Bible states: "Since life was viewed as sacred (Genesis 9.6), no amount of blood money could be given as recompense for the loss of the life of an innocent person; it had to be "life for life" (Exodus 21.23; Deuteronomy 19.21)".[7]

Early Confucianism

[edit]Confucius had demanded vengeance for the killing of parents, older brothers, and friends, and viewed this as a matter of duty.[8] Book of Rites quotes Confucius saying: "(a son whose parent was killed) should sleep on straw, with his shield for a pillow; he should not take office; he must be determined not to live with the slayer under the same heaven. If he meet with him in the marketplace or the court, he should not have to go back for his weapon, but instantly fight with him."[9]

Feuds in the Middle Ages and Renaissance era

[edit]

Medieval Europe in general

[edit]According to historian Marc Bloch:

The Middle Ages, from beginning to end, and particularly the feudal era, lived under the sign of private vengeance. The onus, of course, lay above all on the wronged individual; vengeance was imposed on him as the most sacred of duties ... The solitary individual, however, could do but little. Moreover, it was most commonly a death that had to be avenged. In this case the family group went into action and the faide (feud) came into being, to use the old Germanic word which spread little by little through the whole of Europe—'the vengeance of the kinsmen which we call faida', as a German canonist expressed it. No moral obligation seemed more sacred than this ... The whole kindred, therefore, placed as a rule under the command of a chieftain, took up arms to punish the murder of one of its members or merely a wrong that he had suffered.[10]

Rita of Cascia, a popular 15th-century Italian saint, was canonized by the Catholic Church due mainly to her great effort to end a feud in which her family was involved and which claimed the life of her husband.

Northern Europe

[edit]The Celtic phenomenon of the blood feud demanded "an eye for an eye", and usually descended into murder. Disagreements between clans might last for generations in Scotland and Ireland.

In Scandinavia in the Viking era, feuds were common, as the lack of a central government left dealing with disputes up to the individuals or families involved. Sometimes, these would descend into "blood revenges", and in some cases would devastate whole families. The ravages of the feuds as well as the dissolution of them is a central theme in several of the Icelandic sagas.[11] An alternative to feud was blood money (or weregild in the Norse culture), which demanded a set value to be paid by those responsible for a wrongful permanent disfigurement or death, even if accidental. If these payments were not made, or were refused by the offended party, a blood feud could ensue.[12]

Violence was common in Viking Age Norway. An examination of Norwegian human remains from the Viking Age found that 72% of the examined males and 42% of the examined females had suffered weapon-related trauma. Violence was less common in Viking Age Denmark, where society was more centralized and complex than the clan-based Norwegian society.[13]

In Iceland, blood feuds occurred until the 16th century.[14]

Holy Roman Empire

[edit]At the Holy Roman Empire's Reichstag at Worms in 1495 AD, the right of waging feuds was abolished. The Imperial Reform proclaimed an "eternal public peace" (Ewiger Landfriede) to put an end to the abounding feuds and the anarchy of the robber barons, and it defined a new standing imperial army to enforce that peace. However, it took a few more decades until the new regulation was universally accepted.[citation needed] In 1506, for example, knight Jan Kopidlansky killed a family rival in Prague, and the town councillors sentenced him to death and had him executed. His brother, Jiri Kopidlansky, declared a private war against the city of Prague.[15] Another case was the Nuremberg-Schott feud, in which Maximilian was forced to step in to halt the damages done by robber knight Schott.

Spain

[edit]In the Spanish Late Middle Ages, the Vascongadas was ravaged by the War of the Bands, which were bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In the region of Navarre, next to Vascongadas, these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, in Vascongadas, the two major warring factions were named Oinaz and Gamboa. (Cf. the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures ("towers") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fires, and sometimes by royal decree.

Samurai honours and feuds

[edit]In Japan's feudal past, the samurai class upheld the honor of their family, clan, and their lord by katakiuchi (敵討ち), or revenge killings. These killings could also involve the relatives of an offender. While some vendettas were punished by the government, such as that of the Forty-seven Ronin, others were given official permission with specific targets.

Feuds in modern times

[edit]

Blood feuds are still practised in some areas in:

- France (especially Corsica and within Manush communities)

- Sardinia[18][19] where a blood feud is called in the local language "Disamistade".

- Ireland (especially Dublin and Limerick)

- Between Mafia families in Southern Italy (especially Sicily, Campania, Calabria, Apulia and other areas of the same territory)[20] and neighbouring Malta

- Greece (Mani and Crete)[21][22]

- Between White British, British Asian or Black British working-class families, crime groups, street gangs, football firms and family clans throughout Britain and Ireland.[23][24] Feuds amongst Traveller clans are also relatively common throughout Britain and Ireland.[25] Multiple diaspora communities also partake in feuding, such as Turkish, Albanian and Kurdish communities.

- Between rival crime families in Galicia, Spain

- Between so-called woonwagenbewoners (ethnic Dutch people who live in mobile homes) in the Netherlands[26]

- Among Kurdish and Turkish clans in Turkey (as well as between Kurdish clans in Iraq and Iran)[27][28]

- Between Turkish Cypriots

- Between rival clans in northern Albania and Kosovo

- Between Canadian Aboriginal tribes

- Among Pashtuns in Afghanistan[29]

- Among tribes of Montenegro[30]

- Among Somali clans[31]

- Among the Berbers of Algeria and Morocco[32]

- Egypt (especially among the Saidi people in Upper Egypt[33])

- Between Yoruba and Igbo clans over land in Nigeria[34]

- Between clans in India[35] and between rival tribes in the north-east Indian state of Assam

- Among Sikh clans in Punjab[36]

- Rayalaseema of Andhra Pradesh in India

- Between Mirpuri clans in Azad Kashmir (as well as between British Pakistanis of Mirpuri descent in England)[37][38]

- Among rival clans in China, and especially in Fujian and Guangdong provinces[39][40]

- In the Philippines[41] (especially in Mindanao between Muslim Moro and Christian Cebuano clans)[42]

- Between Burakumin clans in Japan[43]

- In the lawless Wa territories of northern Burma[citation needed]

- Among the Arab Bedouins and other Arab tribes inhabiting the mountains of Yemen[44]

- Between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq[44]

- Among Palestinian clans in Gaza[45]

- Between Maronite clans,[46] and between Shiites and Sunnis, in Lebanon

- Between Mhallami clans in Lebanon[47]

- Among the Amhara in Ethiopia

- Among the highland tribes of New Guinea[48]

- In Svaneti, in Georgia (especially between Svan clans)[49]

- In the mountainous areas of Dagestan[citation needed]

- Between Kyrgyz and Uzbek clans[50]

- Between Yazidi clans in Armenia and Azerbaijan[citation needed]

- In republics of the northern Caucasus, such as Chechnya and Ingushetia[51]

- Among Chechen teips where those seeking retribution do not accept or respect the local law enforcement authority[citation needed]

- Among the Madurese people in Indonesia (carok)

Gang warfare/mob war

[edit]

During a fight at a carnival celebration in 1991 two young men from the 'Ndrangheta crime organization were killed, leading to a series of feuds between rival clans.[52] Blood feuds within Russian communities do exist (mostly related to criminal gangs), but are neither as common nor as pervasive as they are in the Caucasus.[citation needed] In the United States, gang warfare also often takes the form of blood feuds. A mob war is a time when two or more rival families/gangs begin open warfare with one another, destroying each other's businesses and assassinating family members. Mafia/Mob wars are generally disastrous for all concerned, and can lead to the rise or fall of a family or gang. African-American, Italian-American, Cambodian, Cuban Marielito, Dominican, Guatemalan, Haitian, Hmong, Sino-Vietnamese Hoa, Irish-American, Jamaican, Korean, Laotian, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran and Vietnamese gangs and organized crime conflicts very often have taken the form of blood feuds, in which a family member in the gang is killed and a relative takes revenge by killing the murderer as well as other members of the rival gang. This can also be observed in particular cases in conflicts among Colombian, Mexican, Brazilian, and other Latin American gangs, drug cartels, and paramilitary groups; in turf wars among Cape Coloured gangs in South Africa; in gang fights among Dutch Antillean, Surinamese and Moluccan gangs in the Netherlands; and in criminal feuds between Scottish, White British, Black and Mixed British gangs in the UK. This has resulted in gun violence and murders in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Ciudad Juarez, Medellin, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, Amsterdam, London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, to name just a few. The Five Families of New York City New York go to great lengths to avoid a war, as not only do the families lose considerable money and valuable men, gangland killings also cause public outrage and can trigger mass crackdowns from authorities like the FBI.

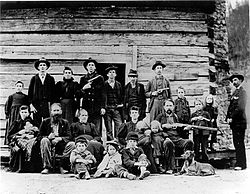

Southern United States

[edit]Blood feuds also have a long history within the White Southerner population (and in particular among the "Scots-Irish" or Ulster Scots American population) of the Southern United States, where it is called the "culture of honor", and still exists to the present day.[53] A series of prolonged violent engagements in late nineteenth-century Kentucky and West Virginia were referred to commonly as feuds, a tendency that was partly due to the nineteenth-century popularity of William Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott, both of whom had written semihistorical accounts of blood feuds. These incidents, the most famous of which was the Hatfield–McCoy feud, were regularly featured in the newspapers of the eastern U.S. between the Reconstruction Era and the early twentieth century, and are seen by some as linked to a Southern culture of honor with its roots in the Scots-Irish forebears of the residents of the area.[54] Another prominent example was the Regulator–Moderator War, which took place between rival factions in the Republic of Texas. It is sometimes considered the largest blood feud in American history.[55]

Greece

[edit]

In Greece, the custom of blood feud is found in several parts of the country, for instance in Crete and Mani.[56] Throughout history, the Maniots have been regarded by their neighbors and their enemies as fearless warriors who practice blood feuds, known in the Maniot dialect of Greek as "Γδικιωμός" (Gdikiomos). Many vendettas went on for months, some for years. The families involved would lock themselves in their towers and, when they got the chance, would murder members of the opposing family. The Maniot vendetta is considered the most vicious and ruthless;[citation needed] it has led to entire family lines being wiped out. The last vendetta on record required the Greek Army with artillery support to force it to a stop. Regardless of this, the Maniot Greeks still practice vendettas, even today. Maniots in America, Australia, Canada and Corsica still have on-going vendettas which have led to the creation of mafia families known as "Γδικιωμέοι" (Gdikiomeoi).[57][failed verification]

Corsica

[edit]In Corsica, vendettas were a social code (mores) that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged the family honor. Between 1821 and 1852, no less than 4,300 murders were perpetrated in Corsica.[58]

Caucasus

[edit]

Leontiy Lyulye, an expert on conditions in the Caucasus, wrote in the mid-19th century: "Among the mountain people the blood feud is not an uncontrollable permanent feeling such as the vendetta is among the Corsicans. It is more like an obligation imposed by the public opinion." In the Dagestani aul of Kadar, one such blood feud between two antagonistic clans lasted for nearly 260 years, from the 17th century until the 1860s.[59]

Albania

[edit]

In Albania, gjakmarrja (blood feuding) is a tradition. Blood feuds in Albania trace back to the Kanun, this custom is also practiced among the Albanians of Kosovo. It returned to rural areas after more than 40 years of being abolished by Albanian Communists led by Enver Hoxha.

In 1980, Albanian author Ismail Kadare published Broken April, about the centuries-old tradition of hospitality, blood feuds, and revenge killing in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s.[60][61] The New York Times, reviewing it, wrote: "Broken April is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country. You know it must happen because that is the way life is lived in these mountains. Insults must be avenged; family honor must be upheld...."[62] The novel was made into a 2001 movie entitled Behind the Sun by filmmaker Walter Salles, set in 1910 Brazil and starring Rodrigo Santoro, which was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[63]

There are now more than 1,600 families who live under an ever-present death sentence because of feuds.[64] and since 1991, some 12,000 people were killed in them.[65]

Kosovo

[edit]Blood feuds have also been part of a centuries-old tradition in Kosovo, tracing back to the Kanun, a 15th-century codification of Albanian customary rules. In the early 1990s, most cases of blood feuds were reconciled in the course of a large-scale reconciliation movement to end blood feuds led by Anton Çetta.[66] The largest reconciliation gathering took place at Verrat e Llukës on 1 May 1990, which had between 100,000 and 500,000 participants. By 1992, the reconciliation campaign ended at least 1,200 deadly blood feuds, and in 1993, not a single homicide occurred in Kosovo.[66][67]

Republic of Ireland

[edit]Criminal gang feuds also exist in Dublin, Ireland and in the Republic's third-largest city, Limerick. Traveller feuds are also common in towns across the country. Feuds can be due to personal issues, money, or disrespect, and grudges can last generations. Since 2001, over 300 people have been killed in feuds between different drugs gangs, dissident republicans, and Traveller families.[68][failed verification]

Philippines

[edit]Family and clan feuds, known locally as rido, are characterized by sporadic outbursts of retaliatory violence between families and kinship groups, as well as between communities. It can occur in areas where the government or a central authority is weak, as well as in areas where there is a perceived lack of justice and security. Rido is a Maranao term commonly used in Mindanao to refer to clan feuds. It is considered one of the major problems in Mindanao because, apart from numerous casualties, rido has caused destruction of property, crippled local economies, and displaced families.

Located in the southern Philippines, Mindanao is home to a majority of the country's Muslim community, and includes the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. Mindanao "is a region suffering from poor infrastructure, high poverty, and violence that has claimed the lives of more than 120,000 in the last three decades."[69] There is a widely held stereotype that the violence is perpetrated by armed groups that resort to terrorism to further their political goals, but the actual situation is far more complex. While the Muslim-Christian conflict and the state-rebel conflicts dominate popular perceptions and media attention, a survey commissioned by The Asia Foundation in 2002—and further verified by a recent Social Weather Stations survey—revealed that citizens are more concerned about the prevalence of rido and its negative impact on their communities than the conflict between the state and rebel groups.[70] The unfortunate interaction and subsequent confusion of rido-based violence with secessionism, communist insurgency, banditry, military involvement and other forms of armed violence shows that violence in Mindanao is more complicated than what is commonly believed.

Rido has wider implications for conflict in Mindanao, primarily because it tends to interact in unfortunate ways with separatist conflict and other forms of armed violence. Many armed confrontations in the past involving insurgent groups and the military were triggered by a local rido. The studies cited above investigated the dynamics of rido with the intention of helping design strategic interventions to address such conflicts.

Causes

[edit]The causes of rido are varied and may be further complicated by a society's concept of honor and shame, an integral aspect of the social rules that determine accepted practices in the affected communities. The triggers for conflicts range from petty offenses, such as theft and jesting, to more serious crimes, like homicide. These are further aggravated by land disputes and political rivalries, the most common causes of rido. Proliferation of firearms, lack of law enforcement and credible mediators in conflict-prone areas, and an inefficient justice system further contribute to instances of rido.

Statistics

[edit]Studies on rido have documented a total of 1,266 rido cases between the 1930s and 2005, which have killed over 5,500 people and displaced thousands. The four provinces with the highest numbers of rido incidences are: Lanao del Sur (377), Maguindanao (218), Lanao del Norte (164), and Sulu (145). Incidences in these four provinces account for 71% of the total documented cases. The findings also show a steady rise in rido conflicts in the eleven provinces surveyed from the 1980s to 2004. According to the studies, during 2002–2004, 50% (637 cases) of total rido incidences occurred, equaling about 127 new rido cases per year. Out of the total number of rido cases documented, 64% remain unresolved.[70]

Resolution

[edit]Rido conflicts are either resolved, unresolved, or reoccurring. Although the majority of these cases remain unresolved, there have been many resolutions through different conflict-resolving bodies and mechanisms. These cases can utilize the formal procedures of the Philippine government or the various indigenous systems. Formal methods may involve official courts, local government officials, police, and the military. Indigenous methods to resolve conflicts usually involve elder leaders who use local knowledge, beliefs, and practices, as well as their own personal influence, to help repair and restore damaged relationships. Some cases using this approach involve the payment of blood money to resolve the conflict. Hybrid mechanisms include the collaboration of government, religious, and traditional leaders in resolving conflicts through the formation of collaborative groups. Furthermore, the institutionalization of traditional conflict resolution processes into laws and ordinances has been successful with the hybrid method approach. Other conflict-resolution methods include the establishment of ceasefires and the intervention of youth organizations.[70]

Well-known blood feuds

[edit]

- Three Kingdoms period, feuding warlords during the fall of the Han dynasty (184–280 AD; China)

- Njál's saga, an Icelandic account of a Norse blood feud (960–1020; Iceland, Ireland and Norway)

- Svyatoslavychi Feud (975/977–980) in Kyivan Rus'

- The Mackintosh-Cameron feud (1290s–1665; Scotland)

- The Battle of the North Inch; the battle is fictionalised in the novel The Fair Maid of Perth by Sir Walter Scott (Michaelmas 1396; Scotland)

- The Krummedige-Tre Rosor feud (1448–1502; Norway)

- The Bonville–Courtenay feud (1450s; England)

- The Percy–Neville feud (1450s; England)

- The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487; England)

- The Talbot–Berkeley feud (1455–1485 England; concurrent with the Wars of the Roses)

- The Gunn–Keith feud (1464–1978; Scotland)

- The Campbell–MacDonald feud, including the Massacre of Glencoe (1692; Scotland)

- The Clan Forbes–Clan Gordon feud, (1500s–1571; Scotland)

- The Clan Forbes–Clan Leslie feud, (1520s–1530s; Scotland)

- The Clan Kerr-Clan Scott feud, (1526–1565; Scotland)

- The Clan Forbes–citizens of Aberdeen feud, (1529–1539; Scotland)

- The Regulator-Moderator War, (1839–1844; Republic of Texas)

- The Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, (1855–1868; Guangdong, China)

- The Donnelly–Biddulph community feud (1857–1880; Ontario, Canada)

- The Lincoln County War (1878–1881; New Mexico, United States)

- The Lincoln County Feud (1878–1890; West Virginia, United States)

- The Hatfield-McCoy feud (1878–1891; West Virginia & Kentucky, United States)

- The Clanton/McLaury–Earp feud (see also Earp Vendetta Ride), also known as the "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" (1881; Arizona, United States)

- The Pleasant Valley War, also known as the "Tonto Basin Feud" (1882–1892; Arizona, United States)

- The Karađorđević–Obrenović feud (1817–1903; Serbia)

- The Capone–Moran feud, including the St. Valentine's Day massacre (1925–1930; Chicago, Illinois, United States)

- The Castellammarese War (1929–1931; New York City, New York United States)

- The Battle of the Sunset Strip (1947–1951; Los Angeles, California United States)

- The First Colombo Family War (1960–1963; New York City, United States)

- The Second Colombo Family War (1971–1975; New York City, United States)

- The Riccobene War (1982–1984; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States)

- The Internal Patriarca War (1991–1996; Boston, Massachusetts, United States)

- Great Mafia War (1981–1983; Sicily, Italy)

- The Feud of Scampia (2004–2005; Naples, Italy)

- The Maguindanao Massacre (2009; Ampatuan, Philippines)

- The Limerick feud (2000–present; Limerick, Ireland)

- The Montreal Mafia War (2009–present; mostly the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario)

See also

[edit]- Alastor, Greek daemon of blood feuds and generational guilt

- Blood Law

- Communal conflicts in Nigeria

- Dassler brothers feud

- Endemic warfare

- Ethnic violence in South Sudan

- Feud (professional wrestling)

- Frontier justice

- Gjakmarrja

- Kin punishment

- List of feuds in the United States

- Mobbing

- Punti–Hakka Clan Wars

- San Luca feud

- Sippenhaft

- Sudanese nomadic conflicts

- Warrior

References

[edit]- ^ "Revenue, Lordship, Kinship & Law". Manaraefan.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Boehm, Christopher (1984). Blood Revenge: The Anthropology of Feuding in Montenegro and Other Tribal Societies. Lawrence, Kansas: The University of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0245-2.

- ^ Gluckman, Max. "The Peace in the Feud". Past and Present, 1955, 8(1):1–14

- ^ "Definition of vendetta". Merriam-Webster dictionary online. Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Keeley, Lawrence H. War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage Oxford University Press, 1996

- ^ Griffiths, John Gwyn (1991), The Divine Verdict: A Study of Divine Judgement in the Ancient Religions, Brill, p. 90, ISBN 978-90-04-09231-0

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (1993), The Oxford Companion to the Bible, Oxford University Press, p. 68, ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8

- ^ Weber, Max (1951), The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, Free Press, p. 169, ISBN 9780029344507

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Legge, James (1910), "The Than Kung", Sacred Books of the East, vol. 27, Oxford University Press

- ^ Marc Bloch, trans. L. A. Manyon, Feudal Society, Vol. I, 1965, p. 125–126

- ^ Lindow, J. "Bloodfeud and Scandinavian Mythology" (PDF). Freie Universitãt, Berlin. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Miller, William Ian (1990). Bloodtaking and peacemaking : feud, law, and society in Saga Iceland. Chicago. ISBN 0226526801.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bill, Jan; Jacobson, David; Nagel, Susanne; Strand, Lisa Mariann (September 2024). "Violence as a lens to Viking societies: A comparison of Norway and Denmark". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 75 101605. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2024.101605. hdl:10852/114115.

- ^ Helgi Þorláksson (2017). "Atrocious Icelanders versus Basques. Unexpected violence or not?". Jón Guðmundsson lærði's True Account and the Massacre of Basque Whalers in Iceland in 1615. By Irujo, Xabier; Miglio, Viola. Reno, Nevada: Center for Basque Studies. University of Nevada, Reno. pp. 90–92. ISBN 9781935709831.

- ^ "Krvavá msta Jiřího z Kopidlna". Novinky.cz (in Czech). 6 March 2022.

- ^ Lewis, William H. (March 1961). "Feuding and social change in Morocco". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 5 (11): 43–54. doi:10.1177/002200276100500106.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea massacre of women and children highlights poor policing, gun influx". ABC News. 11 July 2019.

- ^ Hooper, John (7 February 2007). "Two more die in 56-year Sardinian feud". The Guardian.

- ^ Rome, Tom Kington (16 July 2023). "Ten killed in two-decade family feud".

- ^ "Police search Calabrian village as murders are linked to clan feud". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009.

- ^ Murphy, Brian (14 January 1999). "Vendetta Victims: People, A Village – Crete's 'Cycle Of Blood' Survives The Centuries". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Tsantiropoulos, Aris (2008). "Collective Memory and Blood Feud; The Case of Mountainous Crete" (PDF). Crimes and Misdemeanours. University of Crete. ISSN 1754-0445. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Men jailed for Clydebank murder following family feud". STV News. 12 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Warburton, Dan (26 February 2013). "Paddy Conroy on his feud with Sayers family". Evening Chronicle. ChronicleLive.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Father and son jailed over fatal Traveller 'feud' wedding shooting". 11 May 2018.

- ^ van Dinther, Mac (22 July 1997). "Afschaffen bepleit van aparte aanpak woonwagenbewoners 'Eigen cultuur van bewoners woonwagenkampen is illusie'". De Volkskrant. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Chivers, C. J. (24 February 2003). "Feud Between Kurdish Clans Creates Its Own War". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Schleifer, Yigal (3 June 2008). "In Turkey, a lone peacemaker ends many blood feuds". The Christian Science Monitor. CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim (10 December 2009). "Independent Appeal: The Afghan peace mission". The Independent. London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Veselin Konjević. "Osvetio jedinca posle 14 godina [Revenge Killing after 14 years]". Глас Jавности [Glas Javnosti]. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Somali feuding 'tit-for-tat'". South Africa: News24.com. 19 January 2004. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Wilkin, Anthony. (1900). Among the Berbers of Algeria. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp. 253.

- ^ Lohr, Sabina (19 September 2016). "The Tradition of Family Revenge Killings in Upper Egypt". Connect the Cultures.

- ^ "Nigeria deploys troops after 14 killed in land feud". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008 – via www.alertnet.org.

- ^ "India's gangster nation". Asia Times Online. ATimes.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "The Voice from the Rural Areas: Muslim-Sikh Relations in the British Punjab, 1940–47". Academy of the Punjab in North America (APNAorg.com). Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Walsh, Declan; Carter, Helen; Lewis, Paul (21 May 2010). "Mother, father and daughter gunned down in cemetery on visit to Pakistan". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Tony (20 January 2001). "Asian blood feuds spill into Britain". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Fincher, John H. (1981). Chinese Democracy: The Self-government Movement in Local, Provincial and National Politics, 1905–1914. Croom Helm. ISBN 9780709904632. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ WuDunn, Sheryl (17 January 1993). "Clan Feuds, an Old Problem, Are Still Threatening Chinese". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Conde, Carlos H. (26 October 2007). "Clan feuds fuel separatist violence in Philippines, study shows". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "DotPH domains available portal". Archived from the original on 24 November 2020.

- ^ Andersson, René (2000). Burakumin and Shimazaki Tōson's Hakai: Images of Discrimination in Modern Japanese Literature. Lund, Sweden: Lund University. ISBN 978-91-628-4538-4. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ a b Raghavan, Sudarsan (10 August 2007). "In the Land of the Blood Feuds". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Hass, Amira (29 July 2001). "Focus / Fierce Gunbattle in Palestinian Blood-feud Claims Nine Lives". Haaretz. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Nassar, Farouk (31 October 1990). "Maronite power crumbles in Lebanon". Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Libanesische Familienclans: Mord mit Ankündigung". Die Tageszeitung. taz.de. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Squires, Nick (25 August 2005). "Deadly twist to PNG's tribal feuds". BBC News. BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Toria, Malkhaz (25 November 2011). "Theoretical justification of ethnic cleansing in modern Abkhazian historiography". ExpertClub.ge. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Harding, Luke (26 June 2010). "Uzbeks in desperate plea for aid as full horror of ethnic slaughter emerges". The Guardian. TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Vatchagaev, Mairbek (15 November 2012). "Chechen and Ingush Leaders Feud over Burial of Slain Insurgents". Eurasia Daily Monitor. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ A mafia family feud spills over, BBC News, 16 August 2007

- ^ Parsons, Chuck (2013). The Sutton-Taylor Feud: The Deadliest Blood Feud in Texas. University of North Texas Press. p. 400. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm (2008). "Chapter 6". Outliers. citing, for example, David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America.

- ^ Bowman, Bob (15 October 2006). "The Worst Feud". TexasEscapes.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Mani, Greece: A Destination of Unique Beauty and Rich History". Greek Reporter. 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Vendetta". Mani.org.gr. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Gregorovius, Ferdinand. Wanderings in Corsica: Its History and Its Heroes. (1855). p. 196. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Souleimanov, Emil Aslan (25 May 2003). "Chechen society and mentality". Prague Watchdog. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Albanian Revenge". Christian Science Monitor. 24 October 1990.

- ^ David Bellos (15 December 2020). "Why Should We Read Ismail Kadare?". World Literature Today.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (12 December 1990). "Books of The Times; An Albanian Tale of Ineluctable Vengeance". The New York Times.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (21 December 2001). "At the Movies". The New York Times.

- ^ White, Jeffrey (25 May 2008). "Peacemaker breaks the ancient grip of Albania's blood feuds". The Christian Science Monitor. CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "A European gun culture deadlier than America's". 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b Marsavelski, Aleksandar; Sheremeti, Furtuna; Braithwaite, John (2018). "Did Nonviolent Resistance Fail in Kosovo?". The British Journal of Criminology. 58: 218–236. doi:10.1093/bjc/azx002.

- ^ "The Reconciliation of the Blood Feuds Campaign 1990-1991". Oral History Kosovo. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Lally, Conor (9 March 2012). "Gardaí suspect Dublin drug feud link in double killing". The Irish Times. IrishTimes.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Wilfredo Magno Torres III (31 October 2007). "In the Philippines: Conflict in Mindanao". Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Torres, Wilfredo M., ed. (2007). Rido: Clan Feuding and Conflict Management in Mindanao. Makati: The Asia Foundation. p. 348. ISBN 978-971-92445-2-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Boehm, Christopher. 1984. Blood Revenge: The Anthropology of Feuding in Montenegro and Other Tribal Societies. Lawrence: University of Kansas.

- Grutzpalk, Jonas (July 2002). "Blood Feud and Modernity: Max Weber's and Émile Durkheim's Theories" (PDF). Journal of Classical Sociology. 2 (2): 115–134. doi:10.1177/1468795X02002002854. S2CID 145146459. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006.

- Hyams, Paul. 2003. Rancor and Reconciliation in Medieval England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kreuzer, Peter. 2005. "Political Clans and Violence in the Southern Philippines". Frankfurt: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt.

- Miller, William Ian. 1990. Bloodtaking and peacemaking: feud, law, and society in Saga Iceland. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Torres, Wilfredo M. (ed.). 2007. Rido: Clan Feuding and Conflict Management in Mindanao. Makati: The Asia Foundation.

- Torres, Wilfredo M. 2010. "Letting a Thousand Flowers Bloom: Clan Conflicts and Their Management". Challenges to Human Security in Complex Situations: The Case of Conflict in the Southern Philippines. Kuala Lumpur: Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN).

External links

[edit]This section's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (February 2023) |

- BBC: "In pictures: Egypt vendetta ends". May 2005. "One of the most enduring and bloody family feuds of modern times in Upper Egypt has ended with a tense ceremony of humiliation and forgiveness. [...] Police are edgy. After lengthy peace talks, no one knows if the penance—and a large payment of blood money—will end the vendetta which began in 1991 with a children's fight."

- 15 clan feuds settled in Lanao; rido tops cause of evacuation more than war, from the MindaNews website. Posted on 13 July 2007.

- 2 clans in Matanog settle rido, sign peace pact, from the MindaNews website. Posted on 30 January 2008.

- Albania: Feuding families…bitter lives

- Bedouin family feud

- Blood feud in Caucasus

- Blood feud in Medjugorje, 1991-1992

- Blood feuds blight Albanian lives

- Blood feuds tearing Gaza apart

- Blood in the Streets: Subculture of Violence

- Calabrian clan feud suspected in slayings

- Chad: Clan Feuds Creating Tinderbox of Conflict

- Children as teacher-facilitators for peace[permanent dead link], from the Inquirer website. Posted on 29 September 2007.

- Crow Creek Massacre

- Family Feud in Ireland Involves 200 Rioters

- Gang mayhem grips LA

- Gangs clash in Nigerian oil city

- Iraq's death squads: On the brink of civil war

- Mafia feuds bring bloodshed to Naples' streets

- Maratabat and the Maranaos, from the blog of Datu Jamal Ashley Yahya Abbas, originally in "Reflections on the Bangsa Moro." Posted on 1 May 2007.

- Mexico drugs cartels feud erupts

- NZ authorities fear retaliatory attacks between rival gangs

- Rido, from The Asia Foundation's Rido Map website.

- Rido and its Influence on the Academe, NGOs and the Military, an essay from the website of the Balay Mindanaw Foundation, Inc. Posted on 28 February 2007.

- 'Rido' seen [as] major Mindanao security concern[permanent dead link], from the Inquirer website. Posted on 18 November 2006.

- State Attorney: Problems Posed By Haitian Gangs Growing

- Thousands fear as blood feuds sweep Albania

- Tribal Warfare and Blood Revenge

- Tribal warfare kills nine in Indonesia's Papua Archived 17 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Villages in "rido" area return home, from the MindaNews website. Posted on 1 November 2007.

- Violent ethnic war looms between Filipino and Vietnamese gangs

- A "Yakuza War" has started in Central Tokyo

Definition and Etymology

Core Definition

A feud constitutes a prolonged and bitter quarrel marked by mutual enmity, typically between families, clans, or other social groups, and often enduring across generations.[3] Such conflicts frequently stem from perceived offenses, including insults, injuries, or homicides, fostering a cycle of retaliation that resists external mediation.[4] In its most intense manifestations, a feud escalates into a blood feud, defined as retaliatory violence where kin or associates of a victim seek vengeance against the offender's group, perpetuating hostilities through reciprocal killings.[5] This pattern distinguishes feuds from isolated disputes, as they embed within group identities and customary norms, particularly in societies lacking centralized authority to enforce peace.[6] Empirical observations across cultures reveal feuds as mechanisms for restoring honor or balance absent formal legal recourse, though they impose high costs in lives and social cohesion. For instance, anthropological analyses code feuding as blood revenge following homicide, correlating it with segmentary lineage structures where collective liability amplifies individual acts into group obligations.[6] While modern usages extend the term to non-violent rivalries, such as between public figures or corporations, the core anthropological and historical referent emphasizes enduring, kin-based antagonism with potential for violence, as evidenced in cross-cultural datasets linking feuds to low state centralization and pastoral economies.[4]Historical Etymology and Linguistic Variations

The English term "feud" in the sense of prolonged enmity or hostility entered the language around the mid-13th century as fede or feide, denoting a state of hatred or family-based conflict.[7] This derives from Old French faide or feide (12th century), which itself stems from Frankish faida or Proto-West Germanic *faihiþu, rooted in a Proto-Germanic *faihithja- meaning "hostility" or "vendetta," linked to the adjective *faih- ("hostile").[8] [3] Cognates appear across Germanic languages, reflecting shared prehistoric concepts of private revenge. In Old High German, fēhida (9th century) signified enmity or blood feud, paralleling Old English fǣhþ or fǣhþu (attested in texts like Beowulf, circa 1000 CE), which described cycles of violence and retaliation between kin groups.[3] [4] Middle Dutch veijde and Old Norse feið similarly connoted feud or enmity, often regulated under early medieval Germanic laws like the Salic Law (circa 500 CE), where faida permitted compensatory payments (wergild) to avert endless vendettas.[7] Distinct from this enmity sense is an unrelated homonym: "feud" as feudal land tenure (from Medieval Latin feodum, circa 9th century), derived from a Frankish term for "cattle" or property exchange, unrelated to hostility despite superficial phonetic similarity in Old French forms.[9] This feudal meaning, borrowed into English around 1300, later influenced legal terminology but did not merge with the conflict sense until modern usage blurred distinctions in some contexts.[10] Linguistic variations persist in Romance and Germanic descendants: Italian faida (blood feud) and Spanish faida retain the vengeful connotation from Frankish loans, while German Fehde (private war, abolished by imperial edict in 1495) evokes historical knightly quarrels.[3] In Slavic languages, borrowed forms like Polish wenda (vendetta) show indirect influence, but core Indo-European roots emphasize enmity over abstract conflict.[7]Underlying Causes and Mechanisms

Psychological Drivers

Psychological drivers of feuds center on the innate human impulse for revenge, which provides emotional gratification through retaliation and functions evolutionarily to deter exploitation by signaling credible threats of future harm. This instinct manifests as an automatic response to perceived wrongs, activating reward centers in the brain and often overriding rational cost-benefit analysis, thereby initiating cycles of reciprocal violence characteristic of feuds and vendettas.[11] A primary motivator is the restoration of honor, where offenses such as insults or injuries to kin provoke retaliatory acts to reclaim lost social status and avoid the shame of perceived weakness; failure to respond diminishes one's standing within the group, compelling adherence to norms of vengeance even at high personal cost. In cultures emphasizing honor, individuals engage in costly signaling—through disproportionate or ritualized violence—to demonstrate commitment to retaliation, which deters aggressors in environments lacking strong centralized authority, as seen in evolutionary models of "prober-retaliator" strategies where proactive aggression regulates hierarchies but escalates into feuds when mutual signaling fails.[12][13] These drivers perpetuate through emotional amplification, including hatred fueled by group blame and vicarious retribution, where harms to one member justify collective reprisals against out-groups, compounded by cognitive biases that attribute malice broadly and sustain intergenerational commitments via kin loyalty and social pressure. In contexts like Albanian blood feuds under the Kanun code, psychological imperatives of honor (nder) and blood vengeance (gjakmarrja) demand "life for a life" to achieve justice, locking families into endless hakmarrja cycles unless honor is ritually restored, often overriding external mediation due to ingrained distrust and emotional primacy over reason.[11][14]Social and Cultural Dynamics

Feuds frequently arise and persist within societies characterized by a culture of honor, where individuals and groups prioritize reputation and retaliation to deter threats to property or status. In such cultures, social norms dictate that insults or offenses demand vigorous defense, often through violence, to signal resolve and maintain deterrence against future aggressions. This dynamic is particularly evident in pastoralist societies vulnerable to livestock theft, where herding economies historically fostered norms of preemptive aggression and revenge, as substantiated by cross-national analyses linking historical herding prevalence to contemporary attitudes favoring punishment in experimental games.[15] Empirical evidence from the American South illustrates this: regions settled by Scots-Irish herders exhibit elevated homicide rates tied to honor disputes, with experimental studies showing Southerners more prone to aggressive responses to insults compared to Northerners, reflecting ingrained cultural expectations of retaliation.[16] Cultural transmission reinforces these dynamics through socialization, where families and communities instill values of vengeance as a moral imperative, perpetuating feuds across generations. In Albania, the Kanun—a customary code originating in the 15th century—codifies blood feuds (gjakmarrja) as obligatory responses to murder, emphasizing honor restoration via retaliation or negotiated equivalents like blood money or church-mediated forgiveness, with social pressure enforcing compliance to avoid ostracism.[17] Anthropological accounts highlight how such norms foster in-group solidarity by aligning kin against external threats, yet they escalate conflicts through reciprocal obligations, as seen in Mediterranean feuding societies where vendettas serve as mechanisms for enforcing informal justice amid weak state authority.[6] Cross-cultural studies confirm feuds' role in signaling credibility: costly acts of revenge demonstrate commitment to kin defense, reducing predation risks in decentralized social structures, though this often yields net societal costs in sustained violence.[12] These cultural frameworks interact with social structures to sustain feuds, particularly in kin-based or clan systems where collective responsibility amplifies individual disputes into group antagonisms. In honor-oriented communities, failure to avenge erodes familial prestige, compelling participation via reputational incentives rather than mere emotion, as evidenced by ethnographic data from feuding groups showing violence as rational deterrence rather than irrational impulse.[13] While state interventions, such as Albania's post-1990s efforts to mediate via NGOs, have reduced incidences—reporting around 1,400 families in feuds by 2017—residual cultural adherence persists in rural areas, underscoring the resilience of honor norms against modernization.[17] Overall, social and cultural dynamics position feuds as adaptive strategies for order in low-trust environments, albeit at the expense of broader peace.Economic and Environmental Triggers

Economic competition over limited resources, such as land, timber, and livestock, frequently initiates feuds in traditional and agrarian societies where family or clan wealth depends on access to these assets. In pre-industrial economies, disputes arising from theft or encroachment—often starting small, like the alleged theft of a single pig in 1878 between the Hatfield and McCoy families along the Kentucky-West Virginia border—escalate into prolonged vendettas when underlying rivalries over logging rights and timber monopolies intensify scarcity-driven resentments.[18][19] Post-Civil War economic decline in Appalachia, marked by falling opportunities in extractive industries, further fueled such tensions, transforming personal slights into intergenerational conflicts over economic survival.[20] In pastoralist communities, where livestock represent primary wealth and mobility is constrained by terrain, raids for cattle or sheep commonly trigger retaliatory cycles, embedding feuds within cultural norms of honor and revenge. Anthropological studies of herding societies link these patterns to historical environmental suitability for pastoralism, which fosters "cultures of honor" that prioritize violent defense of property against theft, perpetuating feuds as mechanisms for resource enforcement in the absence of centralized authority.[21] Similarly, in Albanian customary law under the Kanun, blood feuds often stem from land disputes or economic harms like property damage, with approximately 15% of homicides in the late 1990s tied to such vendettas amid post-communist economic instability.[22][23] Environmental pressures, including droughts and resource degradation, amplify these economic triggers by heightening scarcity in marginal ecosystems. In arid pastoral regions, such as parts of East Africa and the Sahel, competition for water and grazing lands—exacerbated by climate variability—drives clan conflicts, with studies documenting how reduced pasture availability correlates with increased raids and retaliatory killings.[24][25] Governance failures compound this, as unclear land tenure in mobile herding systems turns episodic scarcity into enduring feuds, distinct from mere predation by emphasizing reciprocal violence over resources essential for clan reproduction.[26][27]Classification of Feuds

Blood Feuds and Vendettas

Blood feuds, also known as vendettas in certain cultural contexts, constitute a subclass of feuds characterized by cycles of retaliatory killings between kinship groups, typically families or clans, to avenge perceived violations of honor such as murder, insult, or property disputes.[28][29] These conflicts adhere to customary codes enforcing obligatory revenge, where failure to retaliate diminishes social standing, perpetuating intergenerational violence until external mediation or exhaustion intervenes.[30] The term "vendetta," derived from Italian meaning "revenge," historically denotes private feuds in Corsica and Sicily, where relatives of a victim systematically target the offender's kin, often escalating into prolonged familial wars.[31][29] In Albania, blood feuds or gjakmarrja ("blood-taking") are codified in the 15th-century Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, mandating revenge killings for offenses against honor, with only adult males as legitimate targets, though families suffer indirect consequences like self-imposed isolation.[32] Suppressed under communist rule from 1944 to 1991, the practice resurged post-regime collapse, with estimates of 9,500 deaths between 1991 and 2008 and thousands of families affected, leading to over 20,000 people in self-confinement by 2008.[33][34] Contemporary data indicate a decline, with only a small number of annual deaths—fewer than 10 reported in recent years—and state efforts including reconciliation committees reducing incidence, though cultural persistence confines hundreds of children indoors for protection.[35][36] The Hatfield-McCoy feud in the Appalachian region of the United States, spanning 1863 to 1891 along the West Virginia-Kentucky border, exemplifies blood feuds in settler societies, ignited by disputes over a stolen pig, Civil War loyalties, and romantic entanglements, resulting in at least 12 confirmed deaths and numerous injuries before legal intervention and a 1888 truce.[37] In Corsica, vendettas historically dominated 19th-century social life, with feuds like those documented by Prosper Mérimée involving banditry and clan warfare, claiming hundreds of lives annually until French centralization curtailed them by the early 20th century.[38] These patterns underscore blood feuds' reliance on weak state authority, where private enforcement of justice fills institutional voids, fostering vendettas that prioritize collective retribution over individual culpability.[39]Familial and Clan-Based Feuds

Familial feuds involve prolonged conflicts between extended families, often escalating through cycles of retaliation for perceived insults, property disputes, or personal harms, while clan-based feuds extend this dynamic to larger kinship networks bound by shared ancestry, territory, or allegiance. These conflicts typically prioritize collective honor and revenge over individual grievances, perpetuating violence across generations until external intervention or exhaustion halts the cycle.[40] The Hatfield-McCoy feud, spanning 1863 to 1891 along the West Virginia-Kentucky border, exemplifies a classic familial feud rooted in post-Civil War tensions and a dispute over a stolen hog. The conflict began with the 1865 killing of Asa Harmon McCoy, a Union sympathizer, allegedly by members of the Hatfield-aligned Logan Wildcats militia, and escalated with the 1878 trial implicating Floyd Hatfield in the hog theft, leading to retaliatory murders including the 1888 New Year's Day attack on the McCoy cabin that killed two family members. By its end, the feud claimed at least 12 lives directly, with Randolph McCoy losing five of his 16 children, though sensationalized accounts inflated totals to around 60 victims over decades.[41][42][40] In clan-based contexts, Scottish Highland feuds often arose from territorial rivalries and loyalty disputes, as seen in the prolonged Forbes-Gordon conflict originating in the 12th-13th centuries over land claims in Aberdeenshire, which intensified in the 1520s with raids and battles culminating in the 1571 assassination of the Earl of Moray, indirectly tied to clan animosities. Another notorious example, the Campbell-MacDonald rivalry, peaked with the 1692 Glencoe Massacre where government forces under Campbell command killed 38 MacDonalds for delayed oath submission, rooted in Jacobite loyalties and clan power struggles rather than mere personal vendetta. These feuds frequently involved cattle raiding and ambushes, with central authority interventions like royal proclamations attempting to curb them by the 17th century.[43][44] Albanian blood feuds, governed by the Kanun customary code emphasizing family honor (besa), represent ongoing clan-based conflicts primarily in northern regions, where a killing obligates retaliatory murder against any male member of the offending clan, often confining survivors to fortified towers. As of 2017-2018 data, approximately 704 families were involved nationwide, with 591 in Albania and 113 abroad, though numbers have declined due to state enforcement and NGOs, with fewer than 10 murders annually reported in recent years. Criminal groups sometimes exploit these feuds for territorial control, complicating resolution efforts.[34][35] Similar patterns persist in Mediterranean enclaves like Greece's Mani Peninsula, where clan vendettas (gdikiomos) historically involved entire families in retaliatory killings over insults or livestock theft, with tower houses serving as defenses; the last major feud in Kitta ended in 1871 after army intervention, though isolated incidents continued into the 20th century. In Sardinia, familial vendettas tied to banditry traditions have yielded extreme longevity, such as a 56-year feud from 1951 claiming 110 victims by 2007 through chained murders, often peaking during winter holidays for opportunistic revenge. These cases underscore how weak state presence and cultural norms of collective retribution sustain clan feuds, contrasting with blood feuds' narrower personal scope by mobilizing broader kin networks.[45][46][47]Political and Ideological Feuds

Political and ideological feuds constitute a subset of conflicts where disagreements over governance structures, power allocation, or fundamental worldviews harden into personal or factional animosities, frequently persisting beyond electoral cycles and prompting retaliatory measures such as smears, purges, or duels. These feuds differ from transient policy disputes by their emphasis on character vilification and existential threats to rivals' legacies, often amplifying divisions within polities. Empirical patterns reveal that such enmities thrive in environments of high-stakes competition, where ideological purity serves as a proxy for loyalty tests, leading to cycles of escalation that undermine institutional stability.[48] A canonical instance unfolded in the early United States between Federalist Alexander Hamilton and Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr, whose rivalry originated in the 1791 New York gubernatorial contest and intensified through mutual accusations of corruption and ambition. Hamilton's systematic efforts to thwart Burr's 1800 vice-presidential bid—via anonymous pamphlets and lobbying—stemmed from his perception of Burr as a self-serving opportunist lacking principled commitment to federal authority, while Burr nursed grievances over Hamilton's dominance in elite networks. The antagonism peaked in a pistol duel on July 11, 1804, at Weehawken, New Jersey, where Burr fatally shot Hamilton, resulting in Burr's subsequent indictment for murder in New York and New Jersey, though he evaded conviction. This event not only ended Hamilton's life but also discredited Burr politically, illustrating how ideological divergences can precipitate lethal personal reckonings.[49][50] In the Soviet context, the feud between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky epitomized intra-ideological strife, rooted in clashing interpretations of Marxist-Leninist doctrine: Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution, advocating global upheaval, versus Stalin's doctrine of socialism in one country, prioritizing Soviet consolidation. Following Vladimir Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin maneuvered Trotsky's ousting from the Communist Party Politburo by 1926, culminating in Trotsky's exile to Kazakhstan in 1928 and expulsion from the USSR in 1929; Stalin's agents then orchestrated Trotsky's assassination with an ice axe on August 21, 1940, in Coyoacán, Mexico, amid fabricated charges of Trotskyist conspiracies that justified widespread purges claiming over 700,000 lives by 1939. This vendetta underscored how doctrinal disputes within authoritarian structures can rationalize eliminationist campaigns, with Stalin's consolidation of power entailing the erasure of rival intellectual lineages.[48] British parliamentary history furnishes the protracted rivalry between Conservative Benjamin Disraeli and Liberal William Gladstone, spanning the 1868–1880 elections and characterized by vitriolic oratory and policy sabotage, such as Disraeli's 1876 acquisition of Suez Canal shares to undercut Gladstone's fiscal critiques. Disraeli derided Gladstone as a sanctimonious "old man in a hurry," while Gladstone assailed Disraeli's imperialism as aristocratic adventurism devoid of moral grounding; their exchanges, peaking in the 1870s over Irish reforms and Balkan crises, polarized Parliament and contributed to alternating single-term governments between 1868 and 1885. This feud highlighted ideological polarization in democratic arenas, where rhetorical escalation sustains enmity across ideological divides without resorting to violence.[51] Such feuds recurrently feature asymmetric power dynamics, with incumbents leveraging state apparatus against ideological challengers, as seen in patterns from Roman populares-optimates clashes to 20th-century totalitarian purges, where initial policy rifts metastasize into existential threats. Quantitative analyses of historical legislatures indicate that intense personal rivalries correlate with reduced legislative productivity, as measured by stalled bills during peak antagonism periods, though causal attribution remains contested due to confounding partisan factors.[49]Historical Evolution

Feuds in Antiquity and Classical Societies

In Homeric Greek society, as depicted in the epics, feuds frequently arose from offenses such as homicide or violations of honor, prompting cycles of retaliation enforced by kin groups to restore balance and deter future aggressions. Personal vengeance was a normative response, with the victim's family obligated to pursue retribution, often escalating into prolonged blood feuds that could span generations and involve collective responsibility among relatives.[52] [53] This mechanism functioned as a form of social control in decentralized communities lacking centralized authority, where failure to avenge a wrong risked communal dishonor and divine displeasure.[52] Prior to the codification of laws in the 7th century BC, such private settlements dominated, as families directly confronted killers, perpetuating vendettas without formal mediation; Draco's constitution of 621 BC marked an early attempt to interrupt these patterns by imposing standardized penalties for murder, aiming to replace endless retaliation with fixed retribution payable to the state or kin.[54] [55] In classical Athens, state homicide courts like the Areopagus handled cases to avert outright feuds, yet underlying enmities persisted, with litigants leveraging trials to settle personal scores amid a culture of competitive honor that scholars characterize as feud-like in its dynamics of rivalry and reprisal.[56] [57] Mythic exemplars, such as the generational blood feud in Aeschylus's Oresteia (produced c. 458 BC), reflect this tension, portraying the House of Atreus's cycle of murders—from Agamemnon's slaying to Orestes's matricide—as emblematic of unchecked vengeance supplanted by emerging legal institutions like the Areopagus, symbolizing the societal shift from kin-based vendettas to public adjudication.[58] In early Roman society, analogous practices existed, with the victim's family initially determining punishment for homicide, enabling private vengeance that could spark disputes, though these were curtailed by the Twelve Tables' regulations around 450 BC, which formalized compensation over perpetual feuding in a more patrician-dominated framework.[59] [60]Medieval Europe and Feudal Systems

In the feudal systems of medieval Europe, spanning roughly the 9th to 15th centuries, feuds emerged as structured private wars between lords, vassals, and noble families, serving as a primary mechanism for enforcing rights, settling territorial disputes, and upholding honor amid fragmented political authority. Central kings and emperors often lacked the coercive power to monopolize violence, compelling nobles to rely on self-help through limited campaigns that included raids, sieges, and reprisals, typically declared via formal notices or cartels to legitimize actions under customary law. These conflicts were integral to feudal reciprocity, where vassals owed military service but could feud against overlords perceived as failing obligations, as seen in the decentralized power structures of post-Carolingian Francia and the Holy Roman Empire.[61][62] Feuds operated within legal and cultural norms that distinguished them from outright anarchy; for example, in the Holy Roman Empire, the Sachsen spiegel (c. 1220–1235), a influential legal code in northern Germany, outlined procedures for initiating feuds, including warnings and proportional responses to avoid escalation into total war, reflecting Germanic traditions of regulated enmity traceable to early medieval tribal customs. In France, guerres privées proliferated during the 12th and 13th centuries, with royal ordinances like the 1259 Ordonnance of Beaucaire attempting to cap feud durations at 40 days and require arbitration, though enforcement remained inconsistent due to noble resistance. English feudalism, bolstered by the Norman Conquest's stronger monarchy, saw fewer overt feuds by the 12th century, as royal courts under Henry II (r. 1154–1189) increasingly channeled disputes into assizes and common law, reducing private violence.[63][64] The Catholic Church intervened to curb feudal feuds' destructiveness, particularly their toll on non-combatants, through the Peace and Truce of God movements originating in Aquitaine around 975–1027. The Peace of God decrees, promulgated at councils like Charroux (989) and Limoges (994), excommunicated violators and shielded peasants, clergy, merchants, and women from pillage, while the Truce of God, formalized by 1027, banned fighting from Thursday evening to Monday morning, on feast days, and during Lent and Advent—effectively restricting warfare to about 80 days annually in theory. These ecclesiastical efforts, enforced via oaths and relics, reflected causal pressures from Viking, Magyar, and Muslim incursions that amplified internal disorder, though their efficacy waned as secular rulers co-opted the framework for political gain, highlighting tensions between spiritual ideals and feudal pragmatism.[62][65] Long-term, feuds perpetuated cycles of vengeance embedded in noble kinship networks, as evidenced in late medieval German archives where familial alliances fueled multi-generational conflicts, yet they also facilitated dispute resolution absent robust state institutions, with truces often brokered by kin or overlords offering compensation akin to wergild. Historians note these practices delayed centralized state formation by entrenching seigneurial autonomy, contributing to economic stagnation through disrupted agriculture—feudal demesnes suffered recurrent ravages, with estimates of up to 20–30% crop losses in feud-prone regions like the Rhineland during the 14th century. By the 15th century, as monarchies like France under Charles VII (r. 1422–1461) imposed Landfrieden (perpetual peaces) and standing armies, feuds transitioned toward regulated vendettas or outright suppression, marking the feudal system's gradual erosion.[63][64]Early Modern and Non-European Traditions

In early modern Italy, vendettas functioned as a socially legitimized mechanism for resolving interpersonal and familial conflicts, often escalating into cycles of retaliatory violence that sustained high homicide rates. Historical analyses indicate that vendetta was not merely tolerated but integrated into the cultural fabric, with families and factions pursuing revenge as a matter of honor, distinct from state-administered justice. This practice persisted amid fragmented political authority, where central institutions struggled to suppress private warfare.[66][67] In the Scottish Highlands from the 16th to 18th centuries, clan feuds exemplified organized retaliatory conflicts driven by disputes over territory, livestock, and prestige, frequently involving raids and massacres. Notable examples include the prolonged antagonism between the MacDonalds and MacLeods, marked by atrocities in the late 1500s, and the Mackenzie-Munro rivalry spanning centuries with intermittent battles. These feuds thrived in a kinship-based society where loyalty to the clan chief superseded emerging royal authority, leading to endemic violence until state interventions like the 1745 Jacobite defeat and subsequent disarmament acts curtailed clan autonomy.[68][69] Corsican vendettas during the 17th and 18th centuries adhered to a strict code demanding lethal revenge for insults to family honor, resulting in thousands of deaths and prompting reform efforts by figures like Pasquale Paoli, who in the 1750s established courts to mediate disputes and reduce vendetta excesses under his short-lived independent republic.[70][71] Outside Europe, blood feuds in the Ottoman Balkans, particularly among northern Albanian tribes, were governed by the Kanun, a customary legal code attributed to Lekë Dukagjini in the 15th century and enduring into the early modern period despite Ottoman suzerainty. This system prescribed retaliation for homicide—typically killing a male member of the offender's family—while permitting negotiated truces or exiles, though enforcement varied due to the empire's uneven administrative reach in mountainous regions. Ottoman sultans, including Abdul Hamid II in the late 19th century, condemned the practice as barbaric, yet it persisted as a parallel authority where state law was weak, reflecting broader patterns in tribal societies reliant on kinship for dispute resolution.[72]Feuds in Contemporary Settings

Ongoing Blood Feuds in Traditional Societies

Blood feuds persist in certain traditional societies where customary laws supersede or complement state authority, particularly in regions with weak central governance or strong clan structures. In Albania, gjakmarrja—revenge killings mandated by the Kanun, a medieval customary code—remains active, though declining, mainly in northern rural areas. Families involved often confine males indoors for safety, leading to social isolation and economic hardship.[35] Estimates indicate around 3,000 families engaged in feuds, with over 10,000 deaths since the fall of communism in 1991, triggered by disputes over honor, property, or insults.[73] Homicides linked to these feuds numbered three in 2023 and zero in 2024, reflecting partial state interventions like anti-feud committees and legal prohibitions under Article 78a of the Criminal Code.[74] In Somalia, among pastoralist clans, blood revenge forms a core conflict resolution mechanism alongside self-help violence, sustaining cycles of retaliation in areas beyond effective government control. Clan elders mediate, but failures escalate disputes into prolonged feuds involving kin groups.[75] Such practices contribute to instability in nomadic regions, where over 95% of disputes are handled traditionally rather than through formal courts.[76] Papua New Guinea's highlands witness ongoing tribal payback killings resembling blood feuds, with clashes intensifying due to modern factors like firearms and land pressures. A February 2024 incident in Elema district killed at least 49, part of broader violence claiming hundreds annually across tribes.[77] Another clash that month resulted in 26 deaths, highlighting cycles where initial killings provoke retaliatory raids.[78] Government efforts, including peace ceremonies, yield mixed results amid remote terrain and cultural norms prioritizing vengeance. In Yemen's tribal areas, such as Shabwa, blood feuds endure through revenge obligations, entangling most tribesmen in perpetual cycles, though data on current scale is limited by conflict.[79] These practices underscore how feuds in traditional settings maintain social order via deterrence but hinder development when unmitigated by impartial institutions.Urban Gang and Organized Crime Conflicts

Urban gang conflicts represent a contemporary manifestation of feuds, characterized by protracted cycles of retaliatory violence between rival groups vying for control over drug distribution territories, smuggling routes, and local influence. In the United States, street gangs such as the Crips and Bloods in Los Angeles have sustained a rivalry since approximately 1971, marked by drive-by shootings and assassinations that escalate in response to perceived slights or incursions.[80] These disputes mirror traditional vendettas in their reliance on revenge as a core motivator, though amplified by access to automatic weapons and the economic stakes of the crack cocaine trade in the 1980s and 1990s, which fueled hundreds of annual gang-related homicides nationwide.[81] In Chicago, fragmented gang alliances have driven retaliatory killings, with city data indicating 4,098 gang-related homicides from 2004 to 2024, comprising nearly 60% of total murders in affected periods.[82] Violence often stems from interpersonal disputes that expand into group conflicts, perpetuating cycles where a single shooting prompts reprisals across neighborhoods, independent of centralized gang leadership.[83] Federal surveys corroborate that gang members face victimization risks 60 times higher than the general population, underscoring the self-reinforcing nature of these feuds.[84] Organized crime syndicates extend this pattern on a larger scale, as seen in Mexican cartel wars, where inter-group betrayals and territorial bids have caused over 30,000 homicides annually since 2018.[85] Groups like the Sinaloa Cartel engage in vendetta-style executions following arrests or rival incursions, with recent infighting after a 2024 leadership fracture yielding a 400% homicide surge in affected regions.[86] Similarly, historical mafia conflicts, such as the Sicilian Second Mafia War of the early 1980s, involved over 1,000 deaths from bombings and assassinations amid power struggles, demonstrating how economic imperatives intertwine with honor-bound retaliation in urban organized crime.[87] These modern feuds persist due to weak state enforcement and lucrative illicit markets, contrasting traditional blood feuds by their industrialized lethality yet retaining the causal logic of reciprocal escalation.High-Profile Modern Feuds