Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Myrmecia (ant)

View on Wikipedia

| Myrmecia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bull ant queen in Swifts Creek, Victoria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmeciinae |

| Tribe: | Myrmeciini Emery, 1877 |

| Genus: | Myrmecia Fabricius, 1804[1] |

| Type species | |

| Formica gulosa, now Myrmecia gulosa | |

| Diversity[2][3] | |

| c. 93 species | |

| |

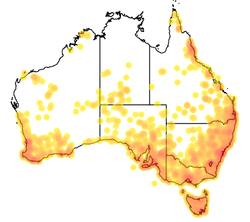

| Occurrences reported to the Atlas of Living Australia as of May 2015 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Halmamyrmecia Wheeler, 1922 | |

Myrmecia is a genus of ants first established by Danish zoologist Johan Christian Fabricius in 1804. The genus is a member of the subfamily Myrmeciinae of the family Formicidae. Myrmecia is a large genus of ants, comprising at least 93 species that are found throughout Australia and its coastal islands, while a single species is only known from New Caledonia. One species has been introduced out of its natural distribution and was found in New Zealand in 1940, but the ant was last seen in 1981. These ants are commonly known as bull ants, bulldog ants or jack jumper ants, and are also associated with many other common names. They are characterized by their extreme aggressiveness, ferocity, and painful stings. Some species are known for the jumping behavior they exhibit when agitated.

Species of this genus are also characterized by their elongated mandibles and large compound eyes that provide excellent vision. They vary in colour and size, ranging from 8 to 40 millimetres (0.31 to 1.57 in). While workers and queens are hard to distinguish from each other due to their similar appearance, males are identifiable by their perceptibly smaller mandibles. Almost all Myrmecia species are monomorphic, with little variation among workers of a given species. Some queens are ergatoid and have no wings, while others have either stubby or completely developed wings. Nests are mostly found in soil, but they can be found in rotten wood and under rocks. One species does not nest in the ground at all; its colonies can only be found in trees.

A queen will mate with one or more males, and during colony foundation she will hunt for food until the brood have fully developed. The life cycle of the ant from egg to adult takes several months. Myrmecia workers exhibit greater longevity in comparison to other ants, and workers are also able to reproduce with male ants. Myrmecia is one of the most primitive group of ants on earth, exhibiting differentiated behaviors from other ants. Workers are solitary hunters and do not lead other workers to food. Adults are omnivores that feed on sweet substances, but the larvae are carnivores that feed on captured prey. Very few predators eat these ants due to their sting, but their larvae are often consumed by blindsnakes and echidnas, and a number of parasites infect both adults and brood. Some species are also effective pollinators.

Myrmecia stings are very potent, and the venom from these ants is among the most toxic in the insect world. In Tasmania, 3% of the human population are allergic to the venom of M. pilosula and can suffer life-threatening anaphylactic reactions if stung. People prone to severe allergic reactions can be treated with allergen immunotherapy (desensitisation).

Etymology and common names

[edit]The generic name Myrmecia derives from Greek word Myrmec- (+ -ia), meaning "ant".[4] In Western Australia, the Indigenous Australians called these ants kallili or killal.[5][better source needed]

Ants of this genus are popularly known as bulldog ants, bull ants, or jack jumper ants due to their ferocity and the way they hang off their victims using their mandibles, and also due to the jumping behaviour displayed by some species.[6] Other common names include "inch ants", "sergeant ants", and "soldier ants".[7][8][9] The jack jumper ant and other members of the Myrmecia pilosula species group are commonly known as "black jumpers", "hopper ants", "jumper ants", "jumping ants", "jumping jacks", and "skipper ants".[10][11][12][13][14]

Taxonomy and evolution

[edit]Genetic evidence suggests that Myrmecia diverged from related groups about 100 million years ago (Mya). The subfamily Myrmeciinae, to which Myrmecia belongs, is believed to have been found in the fossil record of 110 Mya ago.[15] However, one study suggests that the age of the most recent common ancestor for Myrmecia and Nothomyrmecia is 74 Mya, and the subfamily is possibly younger than previously thought.[16] Ants of the extinct genus Archimyrmex may possibly be the ancestor of Myrmecia.[17] In the Evans' vespoid scala, Myrmecia and other primitive ant genera such as Amblyopone and Nothomyrmecia exhibit behavior which is similar to a clade of soil-dwelling families of vespoid wasps.[18] Four species groups form a paraphyletic assemblage while five species groups form a monophyletic assemblage.[19] The following cladogram shows the phylogenetic relationships within Myrmecia:[19]

| Species groups of the genus Myrmecia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

[edit]

Myrmecia was first established by Danish zoologist Johan Christian Fabricius in his 1804 publication Systema Piezatorum, in which seven species from the genus Formica were placed into the genus along with the description of four new species.[20] Myrmecia has been classified into numerous families and subfamilies; in 1858, British entomologist Frederick Smith placed it in the family Poneridae, subfamily Myrmicidae. It was placed in the subfamily Ponerinae by Austrian entomologist Gustav Mayr in 1862.[21][22] This classification was short-lived as Mayr reclassified the genus into the subfamily Myrmicinae three years later.[23] In 1877, Italian entomologist Carlo Emery classified the genus into the newly established subfamily Myrmeciidae, family Myrmicidae.[24] Smith, who had originally established the Myrmicidae as a family in 1851, reclassified them as a subfamily in 1858.[21][25] He again treated them as a family in 1871.[26] Swiss myrmecologist Auguste Forel initially treated the Poneridae as a subfamily and classified Myrmecia as one of its constituent genera but later placed it in the Ponerinae.[27][28] William H. Ashemad placed the genus in the subfamily Myrmeciinae in 1905, but it was later placed back in the Ponerinae in 1910 by American entomologist William Morton Wheeler.[29][30] In 1954, Myrmecia was placed into the Myrmeciinae; this was the last time the genus was placed into a different ant subfamily.[31]

In 1911, Emery classified the subgenera Myrmecia, Pristomyrmecia, and Promyrmecia, based on the shape of their mandibles.[a][32] Wheeler established the subgenus Halmamyrmecia, and the ants placed in it were characterized by their jumping behavior.[33] The taxon Wheeler described was not referred to in his later publications,[34] and the genera Halmamyrmecia and Pristomyrmecia were synonymised by John Clark.[35][36] At the same time, Clark reclassified the subgenus Promyrmecia as a full genus. He revised the whole subfamily Myrmeciinae in 1951, recognizing 118 species and subspecies in Myrmecia and Promyrmecia; five species groups were assigned to Myrmecia and eight species groups to Promyrmecia.[34] This revision was rejected by entomologist William Brown due to the lack of morphological evidence that would make the two genera distinct from each other.[37] Due to this, Brown classified Promyrmecia as a synonym of Myrmecia in 1953.[38] Clark's revision was the last major taxonomic study on the genus before 1991, and only a single species was described in the intervening years.[39][40] In 2015, four new Myrmecia ants were described by Robert Taylor, all exclusive to Australia.[3] Currently, 94 species are described in the genus, but as many as 130 species may exist.[41]

Under the present classification, Myrmecia is the only extant genus in the tribe Myrmeciini, subfamily Myrmeciinae.[27][42] It is a member of the family Formicidae in the order Hymenoptera. The type species for the genus is M. gulosa, discovered by Joseph Banks in 1770 during his expedition with James Cook on HMS Endeavour.[43] M. gulosa is among the earliest Australian insects to be described, and the specimen Banks collected is housed in the Joseph Banks Collection in the Natural History Museum, London.[44] M. gulosa was described by Fabricius in 1775 under the name Formica gulosa and later designated as the type species of Myrmecia in 1840.[45][46]

Genetics

[edit]The number of chromosomes per individual varies from one to over 70 among the species in the genus.[47][48] The genome of M. pilosula is contained on a single pair of chromosomes (males have just one chromosome, as they are haploid). This is the lowest number possible for any animal,[49][50][51] and workers of this species are homologous.[50] Like M. pilosula, M. croslandi also contains a single chromosome.[52][53] While these ants only have a single chromosome, M. pyriformis contains 41 chromosomes, while M. brevinoda contains 42.[54][55] The chromosome count for M. piliventris and M. fulvipes is two and 12, respectively.[56][57] The genus Myrmecia retains many traits that are considered basal for all ants (i.e. workers foraging alone and relying on visual cues).[58]

Species groups

[edit]Myrmecia contains a total of nine species groups.[39] Originally, seven species groups were established in 1911, but this was raised to 13 in 1951; Promyrmecia had a total of eight, while Myrmecia only had five.[59] M. maxima does not appear to be in a species group, as no type specimen is available.[b][60]

| Group name | Common name[61] | Example image | Description | Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. aberrans species group | Wide-jawed bull ants |

|

These medium-to-large ants are distinctive members of the genus. The mandibles and legs are short. They are found in the south-eastern region of Australia, and their colonies are small. Specimens have rarely been collected. | M. aberrans, M. formosa, M. forggatti, M. maura, and M. nobilis[62] |

| M. cephalotes species group | — |

|

These ants are characterised by their bright colours and black heads. Species of this group are medium in size and rare. Colonies dwell inland and they can be found in the eastern and western regions of Australia. | M. callima, M. cephalotes and M. hilli[63] |

| M. gulosa species group | Giant bull ants |

|

Members of this group are large and slender, and have long legs. They are commonly found throughout most of Australia, although they are rarely or never found in the north-western coastal areas and Tasmania[citation needed]; one species has also been introduced to New Zealand. The mandibles vary in shape, and the number of teeth range from three to six. | M. analis, M. arnoldi, M. athertonensis, M. auriventris, M. borealis, M. brevinoda, M. browningi, M. comata, M. desertorum, M. dimidiata, M. erecta, M. esuriens, M. eungellensis, M. fabricii, M. ferruginea, M. flavicoma, M. forceps, M. forficata, M. fulgida, M. fuscipes, M. gratiosa, M. gulosa, M. hirsuta, Myrmecia inquilina, M. midas, M. minuscula, M. mjobergi, M. nigriceps, M. nigriscapa, M. pavida, M. picticeps, M. pulchra, M. pyriformis, M. regularis, M. rowlandi, M. rubripes, M. rufinodis, M. simillima, M. subfasciata, M. tarsata, M. tridentata, and M. vindex[63] |

| M. mandibularis species group | Toothless bull ants |

|

The ants of this group are medium-sized, and can be distinguished from other Myrmecia ants by their oddly shaped mandibles. While their bodies are black, their appendages may vary in colour. They are known to live in the eastern regions of Australia and Tasmania. Colonies have also been found in the south coastal areas and Western Australia. | M. fulviculis, M. fulvipes, M. gilberti, M. luteiforceps, M. mandibularis, M. piliventris and M. potteri[64] |

| M. nigrocincta species group | — |

|

These ants are medium in size with slender bodies and long legs, confined to the east of Australia. Members of this group look similar to those of the M. gulosa species group. | M. flammicollis, M. nigrocincta, and M. petiolata[65] |

| M. picta species group | — |

|

These ants are small and can be found throughout southern Australia. This species group has only two members, making it the smallest of all the species groups. | M. fucosa and M. picta[66] |

| M. pilosula species group | Jack jumper ants |

|

The majority of these ants are small in size, and colouration varies between species. They are distributed throughout Australia and Tasmania, and one member of this group is endemic to New Caledonia. The species group is known to be heterogeneous. | M. apicalis, M. banksi, M. chasei, M. chrysogaster, M. croslandi, M. cydista, M. dispar, M. elegans, M. harderi, M. haskinsorum, M. imaii, M. impaternata, M. ludlowi, M. michaelseni, M. occidentalis, M. pilosula, M. queenslandica, M. rugosa, and M. varians[3][66] |

| M. tepperi species group | Buck-toothed bull ants |

|

These ants are small or medium-sized, and have similar characteristics to the M. pilosula group. They are found in the south-western and south-eastern regions of Australia. | M. acuta, M. clarki, M. swalei, M. tepperi, and M. testaceipes[67] |

| M. urens species group | Baby bull ants |

|

Members of this group are all small, and colouration varies widely between species. Most specimens collected to date are from the coastal regions of Australia. | M. dichospila, M. exigua, M. infima, M. nigra, M. loweryi, M. rubicunda, and M. urens[67] |

Description

[edit]

Myrmecia ants are easily noticeable due to their large mandibles, large compound eyes that provide excellent vision and a powerful sting that they use to kill prey.[68] Each of their eyes contains 3,000 facets, making them the second largest in the ant world.[69] Size varies widely, ranging from 8 to 40 mm (0.31 to 1.57 in) in length.[68][70] The largest Myrmecia species is M. brevinoda, with workers measuring 37 mm (1.5 in); M. brevinoda workers are also the largest in the world.[c][72][73][74] Almost all species are monomorphic, but M. brevinoda is the only known species where polymorphism exists.[6][75] It is well known that two worker subcastes exist, but this does not distinguish them as two different polymorphic forms.[76] This may be due to the lack of food during winter and they could be incipient colonies.[6] The division of labour is based on the size of ant, rather than its age, with the larger workers foraging for food or keeping guard outside the nest, while the smaller workers tend to the brood.[77]

Their colouration is variable; black combined with red and yellow is a common pattern, and many species have golden-coloured pubescence (hair).[78] Many other species are brightly coloured which warns predators to avoid them.[79] The formicine ant Camponotus bendigensis is similar in appearance to M. fulvipes, and data suggest C. bengdigensis is a batesian mimic of M. fulvipes.[80] The number of malpighian tubules differs between castes; in M. dispar, males have 16 tubules, queens range from 23 to 26, and workers have 21 to 29.[81]

Worker ants are usually the same size as each other, although this is not true for some species; worker ants of M. brevinoda, for example, vary in length from 13 to 37 mm (0.51 to 1.46 in).[6] The mandibles of the workers are long with a number of teeth, and the clypeus is short. The antennae consist of 12 segments and the eyes are large and convex. Based on a study on the antennal sensory of M. pyriformis, the antennal sensilla are known to have eight types.[82] Large ocelli are always present.[83]

Queens are usually larger than the workers, but are similar in colour and body shape.[84][83] The head, node, and postpetiole are broader in the queen, and the mandibles are shorter and also broad.[85] Myrmecia queens are unique in that particular species either have fully winged queens, queens with poorly developed wings, or queens without any wings. For example, M. aberrans and M. esuriens queens are ergatoid, meaning that they are wingless.[86] Completely excavated nests showed no evidence of any winged queen residing within them.[87] Some species have queens which are subapterous,[87] meaning they are either wingless or only have rudiments of wings; the queens can be well developed with or without these wing buds.[88] M. nigrocincta and M. tarsata are "brachypterous", where queens have small and rudimentary wings which render the queen flightless.[6][89] Dealated queens with developed wings and thoraces are considered rare. In some species, such as M. brevinoda and M. pilosula, three forms of queens exist, with the dealated queens being the most recognisable.[87]

Males are easy to identify due to their perceptibly broad and smaller mandibles.[84] Their antennae consist of 13 segments, and are almost the same length as the ants' bodies.[21] Ergatandromorph (an ant that exhibits both male and worker characteristics) males are known; in 1985, a male M. gulosa was collected before it hatched from its cocoon, and it had a long but excessively curved left mandible while the other mandible was small. On the right side of its body, it was structurally male, but the left side appeared female. The head was also longer on the female side, its colour was darker, and the legs and prothorax were smaller on the male side.[90] Male genitalia are retracted into a genital cavity that is located in the posterior end of the gaster.[91] The sperm is structurally the same to other animal sperm, forming an oval head with a long tail.[90]

Among the largest larvae examined were those of M. simillima, reaching lengths of 35 mm (1.4 in).[92] The pupae are enclosed in dark cocoons.[83]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

Almost all species in the genus Myrmecia are found in Australia and its coastal islands.[84] M. apicalis is the only species not native to Australia and is only found in the Isle of Pines, New Caledonia.[93][94] Only one ant has ever established nests outside its native range; M. brevinoda was first discovered in New Zealand in 1940[95] and the ant was recorded in Devonport in Auckland in 1948, 1965 and 1981 where a single nest was destroyed.[96] Sources suggest the ant was introduced to New Zealand through human activity; they were found inside a wooden crate brought from Australia.[95] While no eradication attempt was made by the New Zealand government, the ant has not been found in the country since 1981 and is presumed to have been eradicated.[97]

Ants of this genus prefer to inhabit grasslands, forests, heath, urban areas and woodland.[70] Nests are found in Callitris forest, dry marri forest, Eucalyptus woodland and forests, mallee scrub, in paddocks, riparian woodland, and wet and dry sclerophyll forests.[98] They also live in dry sandplains, and coastal plain.[84][99][100] When a queen establishes a new colony, the nest is at first quite simple structurally. The nest gradually expands as the colony grows larger.[101] Nests can be found in debris, decaying tree stumps, rotten logs, rocks, sand, and soil, and under stones.[98][99] While most species nest underground, M. mjobergi is an arboreal nesting species found on epiphytic ferns of the genus Platycerium.[98][102] Two types of nests have been described for this genus: a simple nest with a noticeable shaft inside, and a complex structure surrounded by a mound.[101] Some species construct dome-shaped mounds containing a single entrance, but some nests have numerous holes that are constantly used and can extend several metres underground.[78][70] Sometimes, these mounds can be 0.5 m (20 in) high.[103] Workers decorate these nests with a variety of items, including charcoal, leaves, plant fragments, pebbles, and twigs.[98][99] Some ants use the warmth by decorating their nests with dry materials that heat quickly, providing the nest with solar energy traps.[104][105]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Foraging

[edit]

The genus Myrmecia is among the most primitive of all known living ants, and ants of the genus are considered specialist predators.[106][107] Unlike most ants, workers are solitary hunters, and do not lay pheromone trails; nor do they recruit others to food.[108][109] Tandem running does not occur, and workers carrying other workers as a method of transportation is rare or awkwardly executed.[110][111] Although Myrmecia is not known to lay pheromone trails to food, M. gulosa is capable of inducing territorial alarm using pheromones while M. pilosula can attack en masse, suggesting these ants can also induce alarm pheromones.[104][112] M. gulosa induces territorial alarm behaviour using pheromones from three sources; an alerting substance from the rectal sac, a pheromone found in the Dufour's gland, and an attack pheromone from the mandibular gland.[113][114] Despite Myrmecia ants being among the most primitive ants, they exhibit some behaviours considered "advanced"; adults will sometimes groom each other and the brood, and distinct nest odors exist for each colony.[110]

Most species are diurnal, and forage on the ground or onto low vegetation in search of food, but a few are nocturnal and only forage at night.[98][115] Most Myrmecia ants are active during the warmer months, and are dormant during winter.[116] However, M. pyriformis is a nocturnal species that is active throughout the whole year. M. pyriformis also has a unique foraging schedule;[117] 65% of individuals who went out to forage left the nest in 40–60 minutes, while 60% of workers would return to the nest in the same duration of time at dusk. Foraging workers rely on landmarks for navigation back home.[118] If displaced a short distance, they will scan their surroundings, and then rapidly move in the direction of the nest.[119] M. vindex ants carry dead nest-mates out of their nests and place them on refuse piles, a behaviour known as necrophoresis.[120][121]

Pollination

[edit]While pollination by ants is somewhat rare,[122] several Myrmecia species have been observed pollinating flowers. For example, the orchid Leporella fimbriata is a myrmecophyte which can only be pollinated by the winged male ant M. urens.[123][124][125] Pollination of this orchid usually occurs between April and June during warm afternoons, and may take several days until the short-lived males all die.[126] The flower mimics M. urens queens, so the males move from flower to flower in an attempt to copulate with it.[127][128] M. nigrocincta workers have been recorded visiting flowers of Eucalyptus regnans and Senna acclinis, and are considered a potential pollination vector for E. regnans trees.[129][130][131] Although Senna acclinis is self-compatible, the inability of M. nigrocincta to appropriately release pollen would restrict its capacity to effect pollination.[131] Foraging M. pilosula workers are regularly observed on the inflorescences of Prasophyllum alpinum (mostly pollinated by wasps of the family Ichneumonidae).[132] Although pollinia are often seen in the ants' jaw, they have a habit of cleaning their mandibles on the leaves and stems of nectar-rich plants before moving on, preventing pollen exchange.[132] Whether M. pilosula contributes to pollination is unknown.[104]

Diet

[edit]

Despite their ferocity, adults are nectarivores, consuming honeydew (a sweet, sticky liquid found on leaves, deposited from various insects), nectar, and other sweet substances.[109][110] The larvae, however, are carnivorous. After they reach a certain size, they are fed insects that foragers capture and kill.[133] The workers also regurgitate food for other ants to consume.[134] Young ants are rarely fed food regurgitated by adults.[135] Adult workers prey on a variety of insects and arthropods, such as beetles, caterpillars, earwigs, Ithone fusca, Perga sawflies, and spiders.[116][136][137][138] Other prey include invertebrates such as bees, cockroaches, crickets, wasps and other ants; in particular, workers prey on Orthocrema ants (a subgenus of Crematogaster) and Camponotus, although this is risky since these ants are able to call for help through chemical signals.[136][139][140][141] Slaters, earthworms, scale insects, frogs, lizards, grass seeds, possum feces and kangaroo feces are also collected as food.[142][143] Flies such as the housefly and blowfly are consumed. Some species, such as M. pilosula, will only attack small fly species and ignore larger ones.[90][144] Nests of the social spider Delena cancerides are often invaded by M. pyriformis ants, and nests once housing these spiders are filled with debris such as twigs and leaves by the workers, rendering them useless.[145] These "scorched earth" tactics prevent the spiders competing with the ants.[146] M. gulosa attacks Christmas beetles, but workers later bury them.[147]

Myrmecia is one of the very few genera where the workers lay trophic eggs, or infertile eggs laid as food for viable offspring.[133][148] Workers laying trophic eggs have only been reported in two species; these species are M. forceps and M. gulosa.[149] Depending on the species, colonies specialise in trophallaxis; queens and larvae eat eggs that are laid by worker individuals, but the workers do not feed on eggs.[90] Neither adults nor larvae consume food during winter, but cannibalism among larvae is known to occur throughout the year.[133] The larvae only cannibalise each other; this is most likely to happen when no dead insects are available.[150]

Predators, parasites and associations

[edit]Myrmecia ants deter many potential predators due to their sting. The blindsnake Ramphotyphlops nigrescens consumes the larvae and pupae of Myrmecia,[151][152] while avoiding the potent sting of the adults, which it is vulnerable to.[153] The short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) also eats the eggs and larvae.[154] Nymphs of the assassin bug species Ptilocnemus lemur lure these ants to themselves by trying to make the ant sting them, by waving its hind legs around to attract a potential prey item.[155][156] Body remains of Myrmecia have been found in the stomach contents of the eastern yellow robin (Eopsaltria australis).[157] The Australian magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen), the black currawong (Strepera versicolor), and the white-winged chough (Corcorax melanorhamphos) prey on these ants, but few are successfully taken.[142]

The host association between Myrmecia and eucharitid wasps began several million years ago;[158] M. forficata larvae are the host to Austeucharis myrmeciae, being the first recorded eucharitid parasitoid of an ant, and Austeucharis fasciiventris is a parasitoid to M. gulosa pupae.[159] M. pilosula is affected by a gregarines parasite that changes an ant's colour from their typical black appearance to brown.[160] This was discovered when brown workers were dissected and found to have gregarinasina spores, while black workers showed no spores.[160] Another unidentified gregarine parasite is known to infect the larvae of M. pilosula and other Myrmecia species.[161] This gregarine parasite also softens the ant's cuticle.[162] Other parasites include Beauveria bassiana,[163] Paecilomyces lilacinus,[164] Chalcura affinis, Tricoryna wasps,[165] and various mermithid nematodes.[166]

M. hirsuta and M. inquilina are the only known species in this genus that are inquilines and live in other Myrmecia colonies. An M. inquilina queen has been found in an M. vindex colony.[167][168] Myrmecia is a larval attendant to the butterfly Theclinesthes serpentata (saltbush blue), while some species, particularly M. nigrocincta, enslave other ant species, notably those in the genus Leptomyrmex.[169][170] M. nigriceps ants are able to enter another colony of the same species without being attacked, as they may be unable to recognise alien conspecifics, nor do they try to distinguish nestmates from ants of another colony.[171][172] Formicoxenus provancheri and M. brevinoda share a form of symbiotic relationship known as xenobiosis, where one species of ant will live with another and raise their young separately, with M. brevinoda being the host.[d][173] Solenopsis may sometimes nest in Myrmecia colonies, as a single colony was found to have three or four Solenopsis nests inside.[174] Lagria beetles and rove beetles in the genus Heterothops dwell inside colonies and skinks and frogs have also been found living unharmed within Myrmecia nests.[175][176][177][178] Metacrinia nichollsi, for example, has been reported living inside M. regularis colonies.[179]

Life cycle

[edit]

Like other ants, Myrmecia ants begin as an egg. If the egg is fertilised, the ant becomes a diploid female; if not, it becomes a haploid male.[180] They develop through complete metamorphosis, meaning that they pass through larval and pupal stages before emerging as adults.[181]

During the process of founding a colony, as many as four queens cooperate with each other to find a suitable nesting ground, but after the first generation of workers is born, they fight each other until one queen is left alive.[182] However, occasional colonies are known to have as many as six queens coexisting peacefully in the presence of workers.[183] A queen searches for a suitable nest site to establish her colony, and excavates a small chamber in the soil or under logs and rocks, where she takes care of her young.[184] A queen also hunts for prey instead of staying in her nest, a behaviour known as claustral colony founding.[185][186] Although queens do provide sufficient amounts of food to feed their larvae, the first workers are "nanitics" (or minims), smaller than the smallest workers encountered in older developed colonies.[187] Several species do not have any worker caste, and solitary queens will raid a colony, kill the residing queen, and take over the colony.[70] The first generation of workers may take a while to fully develop into adults; for example, M. forficata eggs take around 100 days to fully develop,[188] while other species may take up to eight months.[189]

Queens lay around eight eggs, but less than half of these eggs develop. Some species, such as M. simillima and M. gulosa, lay their eggs singly on the colony floor, while M. pilosula ants may lay eggs in a clump. These clumps have two to 30 eggs each with no larvae present.[90] Certain Myrmecia species do not lay their eggs singly and form clumps of eggs, instead.[190] The larvae are capable of crawling short distances without the assistance of adult workers,[191] and workers will cover the larvae in dirt to help them spin into a cocoon.[110] If cocoons are isolated from a colony, they are capable of shedding their skins before hatching, allowing themselves to advance to full pigmentation.[192] Sometimes, a newborn can emerge from its pupa without the assistance of other ants.[90] Once these ants are born, they are able to identify distinct tasks, a well known primitive trait.[193] Myrmecia lifespans vary in each species, but their longevity is greater than many ant genera:[188] M. nigrocincta and M. pilosula have a lifespan of one year, while M. nigriceps workers can live up to 2.2 years.[194][195] The oldest recorded worker was a M. vindex, living up to 2.6 years.[196] If a colony is deprived of workers, queens are able to revert to colony-founding behaviours until a sustainable workforce emerges. A colony may also emigrate to a new nesting spot altogether.[110][197]

Reproduction

[edit]

Winged, virgin queens and males, known as alates, appear in colonies during January, before their nuptial flight. Twenty females or fewer are found in a single colony, while males are much more common.[87] The nuptial flight begins at different times for each species; they have been recorded in mid-summer to autumn (January to early April), but there is one case of a nuptial flight occurring from May to July.[182][198][199] Ideal conditions for nuptial flight are hot stormy days with windspeeds of 30 km/h (18 mi/h) and temperatures reaching 30 °C (86 °F), and elevations of 91 metres (300 ft).[90][198] Nuptial flights are rarely recorded due to queens leaving their nest singly, although as many as four queens may leave the nest at the same time.[87] Species are both polygynous and polyandrous, with queens mating with one to ten males.[200] Polygynous and polyandrous societies can occur in a single nest,[201] but particular species are either primarily polygynous or primarily polyandrous. For example, nearly 80% of tested M. pilosula colonies are polygynous[200] while M. pyriformis colonies are mostly polyandrous.[202] Nuptial flight takes place during the morning and can last until late afternoon. When the alates leave the nest, most species launch themselves into the air from trees and shrubs, although others launch themselves off the ground.[203] Queens discharge a glandular secretion from the tergal gland, which males are strongly attracted to.[204] As many as 1,000 alates will gather to mate. A queen was once found to have five or six males attempting to copulate with her.[90] The queen is unable to bear the weight of the large number of males trying to mate with her, and will drop to the ground, with the ants dispersing later on.[198] M. pulchra queens are ergatoid and cannot fly; the males meet the queen out in an open area away from the nest and mate, and these queens do not return to their nest after mating.[203]

Both independent and dependent colony foundation can occur after mating. Isolation by distance (IBD) patterns have been recorded with M. pilosula queens, where nests that tend to be closer together were more genetically related to each other in comparison to other nests further away. Independent colony foundation is closely associated with queens which engage in nuptial flight in areas far from their home colony, showing that dependent colony foundation mostly occurs if they mate near their nest. In some cases, queens could seek adoption into alien colonies if there are no suitable areas to find a nest or independent colony foundation cannot be carried out. Other queens could try to return to their home nest after nuptial flight, but they may end up in another nest near the nest they originally came from.[200] In multiple-queen societies, the egg-laying queens are generally unrelated to one another,[205][206] but one study showed that it is possible for multiple queens in the same colony to be genetically related to each other.[207] Depending on the species, the number of individuals present in a colony can range from 50 to over 2,200 individuals.[101] A colony with less than 100 workers is not considered a mature colony.[208] M. dispar colonies have around 15 to 329 ants, M. nigrocincta have over 1,000, M. pyriformis have from 200 to over 1,400 and M. gulosa have nearly 1,600.[209][210] A colony can last for a number of years. Foraging behaviour among smaller workers which never usually leave the nest can be a sign of a colony's impending demise.[142]

Workers are known to produce their own eggs, but these eggs are unfertilised and hatch into male ants.[211] There is a chance of workers attacking a particular individual who has successfully produced male offspring due to a change in a workers cuticular hydrocarbon; cuticular hydrocarbons are believed to play a vital role in the regulation of reproduction.[212] However, this is not always the case. Myrmecia is one of several ant genera which possess gamergate workers, where a female worker is able to reproduce with mature males when the colony is lacking a queen.[213][214] Myrmecia workers are highly fertile and can successfully mate with males.[215] A colony of M. pyriformis without a queen was collected in 1998 and kept in captivity, during which time the gamergates produced viable workers for three years. Ovarian dissections showed that three workers of this colony mated with males and produced female workers.[216] Queens have bigger ovaries than the workers, with 44 ovarioles while workers have 8 to 14.[90] Spermatheca is present in M. gulosa workers, based on eight dissected individuals showing a spermatheca structurally similar to those found in queens. These spermathecas did not have any sperm. Why the queen was not replaced is still unknown.[90]

Vision

[edit]

While most ants have poor eyesight, Myrmecia ants have excellent vision.[70] This trait is important to them, since Myrmecia primarily relies on visual cues for navigation.[217] These ants are capable of discriminating the distance and size of objects moving nearly a metre away.[218] Winged alates are only active during the day, as they can see better.[219] Members of a colony have different eye structures due to each individual fulfilling different tasks,[219] and nocturnal species have larger ommatidia in comparison to those that are active during the day.[220] Facet lenses also vary in size; for example, the diurnal species M. croslandi has a smaller lens in comparison to M. nigriceps and M. pyriformis which have larger lenses.[221][222] Myrmecia ants have three photoreceptors that can see UV light, meaning they are capable of seeing colours that humans cannot.[223] Their vision is said to be better than some mammals, such as cats, dogs or wallabies.[224] Despite their excellent vision, worker ants of this genus find it difficult to find their nests at night, due to the difficulty of finding the landmarks they use to navigate. They are thus more likely to return to their nests the following morning, walking slowly with long pauses.[225]

Sting

[edit]

Myrmecia workers and queens possess a sting described as "sharp in pain with no burning." The pain may last for several minutes.[226] In the Starr sting pain scale, a scale which compares the overall pain of hymenopteran stings on a four-point scale, Myrmecia stings were ranked from 2–3 in pain, described as "painful" or "sharply and seriously painful".[227][228] Unlike in honeybees, the sting lacks barbs, and so the stinger is not left in the area the ant has stung, allowing the ants to sting repeatedly without any harm to themselves.[229] The retractable sting is located in their abdomen, attached to a single venom gland connected by the venom sac, which is where the venom is accumulated.[230][231] Exocrine glands are known in some species, which produce the venom compounds later used to inject into their victims.[232] Examined workers of larger species have long and very potent stingers, with some stings measuring 6 millimetres (0.24 in).[233]

Interaction with humans

[edit]Myrmecia is one of the best-known genera of ants.[234] Myrmecia ants usually display defensive behaviour only around their nests, and are more timid while foraging.[235] However, most species are extremely aggressive towards intruders; a few, such as M. tarsata, are timid, and the workers retreat into their nest instead of pursuing the intruder.[236] If a nest is disturbed, a large force of workers rapidly swarms out of their nest to attack and kill the intruder.[237] Some species, particularly those of the M. nigrocincta and M. pilosula species groups, are capable of jumping several inches when they are agitated after their nest has been disturbed; jumper ants propel their jumps by a sudden extension of their middle and hind legs.[238][239] M. pyriformis is considered the most dangerous ant in the world by the Guinness World Records.[240] M. inquilina is the only species of this genus that is considered vulnerable by the IUCN, although the conservation status needs updating.[241][242]

Fatalities associated with Myrmecia stings are well known, and have been attested to by multiple sources.[243] In 1931 two adults and an infant girl from New South Wales died from ant stings, possibly from M. pilosula or M. pyriformis.[244] Another fatality was reported in 1963 in Tasmania.[245] Between 1980 and 2000, there were six recorded deaths, five in Tasmania and one in New South Wales.[246] Four of these deaths were due to M. pilosula, while the remaining two died from a M. pyriformis sting. Half of the victims had known ant-sting allergies, but only one of the victims was carrying adrenaline before being stung.[247] Most victims died within 20 minutes of being stung, but one of the victims died in just five minutes from a M. pyriformis sting.[246] No death has been officially recorded since 2003,[248] but M. pilosula may have been responsible for the death of a man from Bunbury in 2011.[249] Prior to the establishment of a desensitisation program, Myrmecia stings caused one fatality every four years.[250]

Venom

[edit]Each Myrmecia species has different venom components, so people who are allergic to ants are advised to stay away from Myrmecia, especially from species they have never encountered before.[251] Based on five species, the median lethal dose (LD50) is 0.18–0.35 mg/kg, making it among the most toxic venoms in the insect world.[252] The toxicity of the venom may have evolved due to the intense predation by animals and birds during the day, since Myrmecia is primarily diurnal.[253] In Tasmania, 2–3% of the human population is allergic to M. pilosula venom.[247][254][255] In comparison, only 1.6% people are allergic to the venom of the western honeybee (Apis mellifera), and 0.6% to the venom of the European wasp (Vespula germanica).[256] In a 2011 Australian ant-venom allergy study, the objective of which was to determine what native Australian ants were associated with ant sting anaphylaxis, 265 of the 376 participants in the study reacted to the sting of several Myrmecia species. Of these, the majority of patients (176) reacted to M. pilosula venom and to those of several other species.[257] In Perth, M. gratiosa was responsible for most cases of anaphylaxis due to ant stings, while M nigriscapa and M. ludlowi were responsible for two cases.[258] The green-head ant (Rhytidoponera metallica) was the only ant other than Myrmecia species to cause anaphylaxis in patients.[257] Dogs are also at risk of death from Myrmecia ants; renal failure has been recorded in dogs experiencing mass envenomation, and one dog was euthanised due to its deteriorating health despite treatment.[259] Sensitivity is persistent for many years.[260] Pilosulin 3 has been identified as a major allergen in M. pilosula venom, while pilosulin 1 and pilosulin 4 are minor allergens.[261][262]

Sting treatment

[edit]

The nature of treatment for a Myrmecia sting depends on the severity of stingose, and the use of antihistamine tablets are other methods to reduce the pain.[263][264] Indigenous Australians use bush remedies to treat Myrmecia stings, such as rubbing the tips of bracken ferns onto the stung area.[265] Carpobrotus glaucescens is also used to treat stung areas, using juices that are squeezed and rubbed onto the area, which quickly relieves the pain from the sting.[266]

Emergency treatment is only needed if a person is showing signs of a severe allergic reaction. Prior to calling for help, stung persons should be laid down, and their legs elevated.[249] An EpiPen or an Anapen is given to people at risk of anaphylaxis, to use in case they are stung.[267] If someone experiences anaphylactic shock, adrenaline and intravenous infusions are required, and those who suffer cardiac arrest require resuscitation.[249] Desensitisation (also called allergy immunotherapy) is offered to those who are susceptible to M. pilosula stings, and the program has shown effectiveness in preventing anaphylaxis.[268][269] However, the standardisation of M. pilosula venom is not validated, and the program is poorly funded.[270][271] The Royal Hobart Hospital and the Royal Adelaide Hospital are the only known hospitals to run desensitisation programs.[11] During immunotherapy, patients are given an injection of venom under the skin. The first dose is small, but dosage gradually increases. This sort of immunotherapy is designed to change how the immune system reacts to increased doses of venom entering the body.[268]

Before venom immunotherapy, whole-body extract immunotherapy was widely used due to its apparent effectiveness, and it was the only immunotherapy used for ant stings.[272][273] However, fatal failures were reported, and this led to scientists to research for alternative methods of desensitisation.[274] Before 1986 allergic reactions were not recorded and there was no study on Myrmecia sting venom; whole body extracts were later used on patients during the 1990s, but this was found to be ineffective and was subsequently withdrawn.[275][276] In 2003, ant venom immunotherapy was shown to be safe and effective against Myrmecia venom.[273]

Prevention

[edit]Myrmecia ants are frequently encountered by humans, and avoiding them is difficult. They defend their nests aggressively, so visible nests should be avoided.[277] Wearing closed footwear such as boots and shoes can reduce the risk of getting stung; these ants are capable of stinging through fabric, however.[278] A risk of being stung while gardening also exists; most stings occur when someone is gardening and is unaware of the ants' presence.[104] Eliminating nearby nests or moving to areas with low Myrmecia populations significantly decreases the chances of getting stung.[276]

Human uses

[edit]Due to their large mandibles, Myrmecia ants have been used as surgical sutures to close wounds.[279]

Cultural representations

[edit]The ant is featured on a postage stamp and on an uncirculated coin which are part of the Things That Sting issue by Australia Post,[280][281] and M. gulosa is the emblem for the Australian Entomological Society.[44] Myrmecia famously appears in the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer's major work, The World as Will and Representation, as a paradigmatic example of strife and constant destruction endemic to the "will to live".[282]

But the bulldog-ant of Australia affords us the most extraordinary example of this kind; for if it is cut in two, a battle begins between the head and the tail. The head seizes the tail in its teeth, and the tail defends itself bravely by stinging the head: the battle may last for half an hour, until they die or are dragged away by other ants. This contest takes place every time the experiment is tried."[282]

Notable Australian poet Diane Fahey wrote a poem about Myrmecia, which is based on Schopenhauer's description,[283] and a music piece written by German composer Karola Obermüller was named after the ant.[284]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Emery did not reclassify the actual genus itself as a subgenus. Instead, he named a subgenus after it.

- ^ Despite M. maxima lacking a specimen, the description Moore provided undoubtedly describes a large Myrmecia species. He describes it as being "nearly an inch and a half long, having very sharp mandibles and a formidable sting, which produces very acute pain."

- ^ This does not include the measurements of queens of both M. brevinoda and other ants. Queens of other species are larger than these workers, with some measuring 52 mm (2.0 in).[71]

- ^ Most likely observed in captive colonies, as F. provancheri is not native to Australia and is only found in Canada and the United States.

References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, Norman F. (19 December 2007). "Myrmecia Fabricius". Hymenoptera Name Server version 1.5. Columbus, Ohio, USA: Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Bolton, B. (2014). "Myrmecia". AntCat. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Robert W. (21 January 2015). "Ants with Attitude: Australian Jack-jumpers of the Myrmecia pilosula species complex, with descriptions of four new species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3911 (4): 493–520. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3911.4.2. hdl:1885/66773. PMID 25661627. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Barrows, Edward M. (2011). Animal behavior desk reference: a dictionary of animal behavior, ecology, and evolution (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. p. 411. ISBN 978-1-43-983651-4.

- ^ Moore, George F. (1842). A descriptive vocabulary of the language in common use amongst the aborigines of Western Australia (PDF). London: W. S. Orr & Co. pp. 54, 58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Clark 1951, p. 18.

- ^ Anderson, Alan (1991). The Ants of Southern Australia. CSIRO Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-64-310235-4.

- ^ Simpson, F.W. (1914). Handbook and Guide to Western Australia. Government Printer. p. 97. OCLC 475502082.

- ^ "The Red Bulldog Ant (E.L.M.)". The Central Queensland Herald. Rockhampton, Qld.: National Library of Australia. 8 December 1932. p. 12. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Clark 1951, pp. 202–204.

- ^ a b Davies, Nathan (30 January 2015). "Angry ants on the march in SA – and can have fatal consequences". Adelaide Now. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Myrmecia pilosula Smith, 1858". Atlas of Living Australia. Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "The Naturalist. Stinging Ants. (Continued)". The Australasian. Melbourne, Victoria: National Library of Australia. 30 May 1874. p. 7. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Jack Jumper Allergy Program". Department of Health and Human Services. Government of Tasmania. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Crozier, R.; Dobric, N.; Imai, H.T.; Graur, D.; Cornuet, J.M.; Taylor, R.W. (March 1995). "Mitochondrial-DNA Sequence Evidence on the Phylogeny of Australian Jack-Jumper Ants of the Myrmecia pilosula Complex" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 4 (1): 20–30. Bibcode:1995MolPE...4...20C. doi:10.1006/mpev.1995.1003. PMID 7620633. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Ward, Philip S.; Brady, Seán G. (2003). "Phylogeny and biogeography of the ant subfamily Myrmeciinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Invertebrate Systematics. 17 (3): 361–386. doi:10.1071/IS02046. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Dlussky, G.M.; Perfilieva, K.S. (2003). "Paleogene ants of the genus Archimyrmex Cockerell, 1923 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmeciinae)" (PDF). Paleontological Journal. 37 (1): 39–47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hasegawa, Eisuke; Crozier, Ross H. (March 2006). "Phylogenetic relationships among species groups of the ant genus Myrmecia". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (3): 575–582. Bibcode:2006MolPE..38..575H. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.021. PMID 16503279.

- ^ Fabricius, Johan Christian (1804). Systema Piezatorum: secundum ordines, genera, species, adiectis synonymis, locis, observationibus, descriptionibus. Brunsvigae: Carolum Reichard. p. 423. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.10490. OCLC 19422437.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b c Smith, Frederick (1858). "Poneridae" (PDF). Catalogue of hymenopterous insects in the collection of the British Museum part VI. London: British Museum. p. 143.

- ^ Mayr, Gustav (1862). "Myrmecologische Studien" (PDF). Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. 12: 649–776. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Mayr, Gustav (1865). Formicidae. In: Novara Expedition 1865. Reise der Österreichischen Fregatte "Novara" um die Erde in den Jahren 1857, 1858, 1859. Zoologischer Theil. Bd. II. Abt. 1. Wien: K. Gerold's Sohn. p. 18.

- ^ Emery, Carlo (1877). "Saggio di un ordinamento naturale dei Mirmicidei e considerazioni sulla filogenesi delle formiche" (PDF). Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana. 9: 67–83. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Smith, Frederick (1851). List of the specimens of British animals in the collection of the British Museum. Part VI. - Hymenoptera Aculeata (PDF). London: British Museum. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Smith, Frederick (1871). "A catalogue of the aculeate Hymenoptera and Ichneumonidae of India and the Eastern Archipelago" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 11 (53): 285–415. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1871.tb02225.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b Forel, Auguste H. (1893). "Sur la classification de la famille des Formicides, avec remarques synonymiques" (PDF). Annales de la Société Entomologique de Belgique. 37: 161–167. doi:10.5281/zenodo.14460.

- ^ Forel, Auguste H. (1885). "Études myrmécologiques en 1884; avec une description des organes sensoriels des antennes" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles. 20: 316–380. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Ashmead, William H. (November 1905). "A skeleton of a new arrangement of the families, subfamilies, tribes and genera of the ants, or the superfamily Formicoidea". The Canadian Entomologist. 37 (11): 381–384. doi:10.4039/Ent37381-11. S2CID 87055448.

- ^ Wheeler, William M. (1910). Ants; their structure, development and behavior. Columbia University press. p. 134. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.1937. ISBN 978-0-23-100121-2. ISSN 0069-6285. LCCN 10008253//r88. OCLC 560205.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Brown, W. L. (March 1954). "Remarks on the internal phylogeny and subfamily classification of the family Formicidae". Insectes Sociaux. 1 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1007/BF02223148. S2CID 33824626.

- ^ Emery, Carlo (1911). "Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Ponerinae" (PDF). Genera Insectorum. 118: 1–125.

- ^ Wheeler, William Morton (1922). "Observations on Gigantiops destructor Fabricius and Other Leaping Ants". Biological Bulletin. 42 (4): 185–201. doi:10.2307/1536521. JSTOR 1536521.

- ^ a b Ogata 1991, p. 354.

- ^ Clark, John (1927). "The ants of Victoria. Part III" (PDF). Victorian Naturalist (Melbourne). 44: 33–40.

- ^ Clark, John (1943). "A revision of the genus Promyrmecia Emery (Formicidae)". Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria. 13: 84: 83–149. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.1943.13.05. ISSN 0083-5986. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Brown, William L. Jr. (1953). "Characters and synonymies among the genera of ants Part I". Breviora. 11 (1–13). ISSN 0006-9698.

- ^ Brown, William (1953). "Revisionary notes on the ant genus Myrmecia of Australia" (PDF). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 111 (6): 1–35. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b Ogata 1991, p. 355.

- ^ Douglas, Athol; Brown, W. L. (March 1959). "Myrmecia inquilina new species: The first parasite among the lower ants" (PDF). Insectes Sociaux. 6 (1): 13–19. doi:10.1007/BF02223789. S2CID 29862128. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Andersen, A.N. (2007). "Ant diversity in arid Australia: a systematic overview" (PDF). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute. 80: 19–51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 11.

- ^ Waterhouse, D. F. (September 1971). "Insects and Australia". Australian Journal of Entomology. 10 (3): 145–160. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1971.tb00025.x.

- ^ a b "Origins". Australian Entomological Society. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Fabricius, Johann Christian (1775). Systema entomologiae, sistens insectorum classes, ordines, genera, species, adiectis synonymis, locis, descriptionibus, observationibus. Flensburgi et Lipsiae: Libraria Kortii. p. 395.

- ^ Swainson, William; Shuckard, W.E. (1840). On the history and natural arrangement of insects. Vol. 104. London, UK: Longman, Brown, Green & Longman's. p. 173. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.32786. LCCN 06013653. OCLC 4329243.

- ^ Gokhman 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Hirai, Hirohisa; Yamamoto, Masa-Toshi; Taylor, Robert W.; Imai, Hirotami T. (September 1996). "Genomic dispersion of 28S rDNA during karyotypic evolution in the ant genus Myrmecia (Formicidae)". Chromosoma. 105 (3): 190–196. doi:10.1007/BF02509500. ISSN 1432-0886. PMID 8781187. S2CID 42343056.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 23.

- ^ a b Crosland, M.W.J.; Crozier, R.H. (1986). "Myrmecia pilosula, an ant with only one pair of chromosomes". Science. 231 (4743): 1278. Bibcode:1986Sci...231.1278C. doi:10.1126/science.231.4743.1278. JSTOR 1696149. PMID 17839565. S2CID 25465053.

- ^ Imai, Hirotami T.; Taylor, Robert W. (December 1989). "Chromosomal polymorphisms involving telomere fusion, centromeric inactivation and centromere shift in the ant Myrmecia (pilosula) n=1". Chromosoma. 98 (6): 456–460. doi:10.1007/BF00292792. ISSN 1432-0886. S2CID 40039115.

- ^ Taylor, Robert W. (November 1991). "Myrmecia croslandi sp.n., a karyologically remarkable new Australian jack-jumper ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 30 (4): 288. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1991.tb00438.x.

- ^ Gadau, Jürgen; Helmkampf, Martin; Nygaard, Sanne; Roux, Julien; Simola, Daniel F.; Smith, Chris R.; Suen, Garret; Wurm, Yannick; Smith, Christopher D. (January 2012). "The genomic impact of 100 million years of social evolution in seven ant species". Trends in Genetics. 28 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.08.005. ISSN 0168-9525. PMC 3314025. PMID 21982512.

- ^ Gokhman 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Imai, Hirotami T.; Crozier, Ross H.; Taylor, Robert W. (1977). "Karyotype evolution in Australian ants". Chromosoma. 59 (4): 341–393. doi:10.1007/BF00327974. ISSN 1432-0886. S2CID 46667207.

- ^ Gokhman 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Imai, Hirotami T.; Taylor, Robert W. (1986). "The exceptionally low chromosome number n= 2 in an Australian bulldog ant, Myrmecia piliventris Smith (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Annual Report of the National Institute of Genetics. 36: 59–61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Qian, Zeng-Qiang; Sara Ceccarelli, F.; Carew, Melissa E.; Schlüns, Helge; Schlick-Steiner, Birgit C.; Steiner, Florian M. (May 2011). "Characterization of Polymorphic Microsatellites in the Giant Bulldog Ant, Myrmecia brevinoda and the jumper ant, M. pilosula". Journal of Insect Science. 11 (71): 71. doi:10.1673/031.011.7101. ISSN 1536-2442. PMC 3281428. PMID 21867438. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Ogata 1991, p. 356.

- ^ Ride, W.D.L.; Taylor, R.W. (1973), "Formica maxima Moore, 1842 (Insecta, Hymenoptera): proposed suppression under the plenary powers in accordance with Article 23(a-b). Z.N.(S.)2023." (PDF), Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 30: 58–60

- ^ Andersen, Alan N (2002). "Common names for Australian ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Australian Journal of Entomology. 41 (4): 285–293. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1009.490. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6055.2002.00312.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Ogata 1991, pp. 356–357.

- ^ a b Ogata 1991, p. 358.

- ^ Ogata 1991, p. 359.

- ^ Ogata 1991, pp. 359–360.

- ^ a b Ogata 1991, p. 361.

- ^ a b Ogata 1991, p. 362.

- ^ a b The World Book Encyclopedia. Chicago, Illinois: Field Enterprises Educational Corp. 1966. p. 466. OCLC 1618918.

- ^ Gronenberg, Wulfila (August 2008). "Structure and function of ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) brains: Strength in numbers" (PDF). Myrmecological News. 11: 25–36. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Australian Museum. "Animal Species: Bull ants". Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 589.

- ^ McWhirter, Norris (1979). Guinness book of world records. New York: Bantam. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-553-12370-8.

- ^ Carwardine, Mark (2008). Animal records. New York, New York: Sterling. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4027-5623-8.

- ^ Archibald, S. B.; Johnson, K. R.; Mathewes, R. W.; Greenwood, D. R. (4 May 2011). "Intercontinental dispersal of giant thermophilic ants across the Arctic during early Eocene hyperthermals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1725): 3679–3686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0729. PMC 3203508. PMID 21543354.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 364.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 318.

- ^ Trager 1988, p. 254.

- ^ a b Clark 1951, p. 121.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 394.

- ^ Merrill, D. N.; Elgar, Mark A. (23 May 2000). "Red legs and golden gasters: Batesian mimicry in Australian ants". Naturwissenschaften. 87 (5): 212–215. Bibcode:2000NW.....87..212M. doi:10.1007/s001140050705. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 10883435. S2CID 34904011.

- ^ Gray, B.; Lamb, K. P. (June 1968). "Some observations on the malpighian tubules and ovarioles in Myrmecia dispar (Clark) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 7 (1): 80–81. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1968.tb00706.x. S2CID 85231938.

- ^ Ramirez-Esquivel, F.; Zeil, J.; Narendra, A. (November 2014). "The antennal sensory array of the nocturnal bull ant Myrmecia pyriformis". Arthropod Structure & Development. 43 (6): 543–558. Bibcode:2014ArtSD..43..543R. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2014.07.004. PMID 25102426.

- ^ a b c Clark 1951, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Clark 1951, p. 21.

- ^ Clark 1951, p. 119.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 305.

- ^ a b c d e Clark 1951, p. 19.

- ^ Clark 1951, p. 11.

- ^ Clark 1951, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Crosland, Michael W. J.; Crozier, Ross H.; Jefferson, E. (November 1988). "Aspects of the Biology of the Primitive Ant Genus Myrmecia F. (Hymenoptera: Formicdae)" (PDF). Australian Journal of Entomology. 27 (4): 305–309. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1988.tb01179.x. S2CID 84418194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014.

- ^ Forbes, James (1967). "The Male Genitalia and Terminal Gastral Segments of Two Species of the Primitive Ant Genus Myrmecia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 75 (1): 35–42. JSTOR 25006039.

- ^ Wheeler, George C. (1971). "Ant larvae of the subfamily Myrmeciinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 47 (4): 245–256.

- ^ Wilson, Edward O. (2013). Letters to a Young Scientist. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-87140-700-9.

Myrmecia apicalis.

- ^ Emery, Carlo (1883). "Alcune formiche della Nuova Caledonia" (PDF). Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana. 15: 145–151. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25416. ISSN 0373-3491.

- ^ a b Keall, J. B. (1981). "A Note on the Occurrence of Myrmecia brevinoda (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in New Zealand". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 18: 203–204. ISSN 0067-0464. JSTOR 42906304. Wikidata Q58677175.

- ^ Lester, Philip J.; Keall, John B. (January 2005). "The apparent establishment and subsequent eradication of the Australian giant bulldog ant Myrmecia brevinoda Forel (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 32 (4): 353–357. doi:10.1080/03014223.2005.9518423. ISSN 0301-4223.

- ^ Lester, Philip J. (4 July 2005). "Determinants for the successful establishment of exotic ants in New Zealand". Diversity and Distributions. 11 (4): 279–288. Bibcode:2005DivDi..11..279L. doi:10.1111/j.1366-9516.2005.00169.x. JSTOR 3696904. S2CID 14289803.

- ^ a b c d e Shattuck, Steve; Barnett, Natalie (June 2010). "Myrmecia Fabricius, 1804". Ants Down Under. CSIRO. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Clark 1951, p. 23.

- ^ Miller, L.J.; New, T.R. (February 1997). "Mount Piper grasslands: pitfall trapping of ants and interpretation of habitat variability". Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria. 56 (2): 377–381. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.1997.56.27. ISSN 0814-1827. LCCN 90644802. OCLC 11628078. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Gray, B. (March 1974). "Nest structure and populations of Myrmecia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with observations on the capture of prey". Insectes Sociaux. 21 (1): 107–120. doi:10.1007/BF02222983. S2CID 11886883.

- ^ Wheeler 1933, p. 17.

- ^ Whinam, J.; Hope, G. (2005). "The Peatlands of the Australasian Region" (PDF). Mires. From Siberia to Tierra del Fuego. Stapfia: 397–433. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d Evans, Maldwyn J. (2008). The Preferred Habitat of the Jack Jumper Ant (Myrmecia pilosula): a Study in Hobart, Tasmania. Invertebrate Biology (Report). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 373.

- ^ Gibb, Heloise; Cunningham, Saul A. (January 2011). "Habitat contrasts reveal a shift in the trophic position of ant assemblages". Journal of Animal Ecology. 80 (1): 119–127. Bibcode:2011JAnEc..80..119G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01747.x. PMID 20831728.

- ^ Andersen, A.N. (1990). "The use of ant communities to evaluate change in Australian terrestrial ecosystems: a review and a recipe". Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia. 16: 347–357.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 402.

- ^ a b "Formicidae - Ants". CSIRO Entomology. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson 2000, p. 424.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 280.

- ^ Frehland, E; Kleutsch, B; Markl, H (1985). "Modelling a two-dimensional random alarm process". Bio Systems. 18 (2): 197–208. Bibcode:1985BiSys..18..197F. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(85)90071-1. PMID 4074854.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, pp. 249, 261.

- ^ Robertson, Phyllis L. (April 1971). "Pheromones involved in aggressive behaviour in the ant, Myrmecia gulosa". Journal of Insect Physiology. 17 (4): 691–715. Bibcode:1971JInsP..17..691R. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(71)90117-X.

- ^ Sheehan, Zachary B. V.; Kamhi, J. Frances; Seid, Marc A.; Narendra, Ajay (2019). "Differential investment in brain regions for a diurnal and nocturnal lifestyle in AustralianMyrmeciaants". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 527 (7): 1261–1277. doi:10.1002/cne.24617. ISSN 0021-9967. PMID 30592041.

- ^ a b Jayatilaka, P.; Narendra, A.; Reid, S. F.; Cooper, P.; Zeil, J. (August 2011). "Different effects of temperature on foraging activity schedules in sympatric Myrmecia ants". Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (16): 2730–2738. Bibcode:2011JExpB.214.2730J. doi:10.1242/jeb.053710. hdl:1885/63066. PMID 21795570.

- ^ Narendra, A.; Reid, S. F.; Hemmi, J. M. (3 February 2010). "The twilight zone: ambient light levels trigger activity in primitive ants". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1687): 1531–1538. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2324. JSTOR 41148678. PMC 2871845. PMID 20129978.

- ^ Narendra, A.; Gourmaud, S.; Zeil, J. (26 June 2013). "Mapping the navigational knowledge of individually foraging ants, Myrmecia croslandi". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1765) 20130683. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0683. PMC 3712440. PMID 23804615.

- ^ Zeil, J.; Narendra, A.; Sturzl, W. (6 January 2014). "Looking and homing: how displaced ants decide where to go". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 369 (1636) 20130034. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0034. PMC 3886322. PMID 24395961.

- ^ Haskins, Caryl P.; Haskins, Edna F. (1974). "Notes on Necrophoric Behavior in the Archaic Ant Myrmecia vindex (Formicidae: Myrmeciinae)". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 81 (2): 258–267. doi:10.1155/1974/80395.

- ^ Neoh, Kok-Boon; Yeap, Beng-Keok; Tsunoda, Kunio; Yoshimura, Tsuyoshi; Lee, Chow-Yang; Korb, Judith (27 April 2012). "Do Termites Avoid Carcasses? Behavioral Responses Depend on the Nature of the Carcasses". PLOS ONE. 7 (4) e36375. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736375N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036375. PMC 3338677. PMID 22558452.

- ^ Beattie, Andrew J.; Turnbull, Christine; Knox, R. B.; Williams, E. G. (1984). "Ant Inhibition of Pollen Function: A Possible Reason Why Ant Pollination is Rare". American Journal of Botany. 71 (3): 421–426. doi:10.2307/2443499. JSTOR 2443499.

- ^ Peakall, Rod (1989). "The unique pollination of Leporella fimbriata (Orchidaceae): Pollination by pseudocopulating male ants (Myrmecia urens, Formicidae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 167 (3–4): 137–148. Bibcode:1989PSyEv.167..137P. doi:10.1007/BF00936402. ISSN 1615-6110. JSTOR 23673944. S2CID 27901569.

- ^ Peakall, Rod; Angus, Craig J.; Beattie, Andrew J. (October 1990). "The significance of ant and plant traits for ant pollination in Leporella fimbriata". Oecologia. 84 (4): 457–460. Bibcode:1990Oecol..84..457P. doi:10.1007/BF00328160. ISSN 1432-1939. JSTOR 4219450. PMID 28312960. S2CID 45589875.

- ^ Peakall, R.; Beattie, A. J.; James, S. H. (October 1987). "Pseudocopulation of an orchid by male ants: a test of two hypotheses accounting for the rarity of ant pollination". Oecologia. 73 (4): 522–524. Bibcode:1987Oecol..73..522P. doi:10.1007/BF00379410. ISSN 1432-1939. JSTOR 4218401. PMID 28311968. S2CID 3195610.

- ^ Pridgeon, Alec M. (2001). Genera Orchidacearum. Volume 2, Orchidoideae (part 1). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-19-850710-9.

- ^ Thompson, John N. (1994). The coevolutionary process. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-226-79759-5.

- ^ Cingel, N. A. van der (2000). An atlas of orchid pollination: America, Africa, Asia and Australia. Rotterdam, South Holland: Balkema. p. 200. ISBN 978-90-5410-486-5.

- ^ Ashton, D.H. (1975). "Studies of flowering behaviour in Eucalyptus regnans F. Muell". Australian Journal of Botany. 23 (3): 399–411. Bibcode:1975AuJB...23..399A. doi:10.1071/bt9750399. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Hawkswoode, T. J. (1981). "Insect pollination of Angophora woodsiana F. M. Bail (Myrtaceae) at Burbank, S. E. Queensland". The Victorian Naturalist. 98 (3): 127. ISSN 0042-5184. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ a b Williams, Geoff; Adam, Paul (2010). The flowering of Australia's rainforests: a plant and pollination miscellany. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-643-09761-2.

- ^ a b Abrol, D.P. (2011). Pollination Biology: Biodiversity Conservation and Agricultural Production (2012 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 288. ISBN 978-94-007-1941-5.

- ^ a b c Freeland, J. (1958). "Biological and social patterns in the Australian bulldog ants of the genus Myrmecia". Australian Journal of Zoology. 6 (1): 1. doi:10.1071/ZO9580001.

- ^ New, Tim R. (30 August 2011). In Considerable Variety: Introducing the Diversity of Australia's Insects. Springer. p. 104. ISBN 978-94-007-1780-0.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 345.

- ^ a b Wheeler 1933, p. 28.

- ^ Wheeler 1933, p. 34.

- ^ Tillyard, R. J. (1922). "The Life-history of the Australian Moth-lacewing, Ithone fusca, Newman (Order Neuroptera Planipennia)". Bulletin of Entomological Research. 13 (2): 205–223. doi:10.1017/S000748530002811X.

- ^ Moffett, Mark W. (May 2007). "Bulldog Ants". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Hnederson, Alan; Henderson, Deanna; Sinclair, Jesse (2008). Bugs alive: a guide to keeping Australian invertebrates. Melbourne: Museum Victoria. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-97-583708-5.

- ^ Ray, Claiborne (19 April 2010). "Acrobatic Ants". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Reid, Samuel F.; Narendra, Ajay; Taylor, Robert W.; Zeil, Jochen (2013). "Foraging ecology of the night-active bull ant Myrmecia pyriformis". Australian Journal of Zoology. 61 (2): 170. doi:10.1071/ZO13027. S2CID 41784912.

- ^ "Red Bull-Ant". Dungog Chronicle: Durham and Gloucester Advertiser. NSW: National Library of Australia. 5 February 1949. p. 2. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Archer, M. S.; Elgar, M. A. (September 2003). "Effects of decomposition on carcass attendance in a guild of carrion-breeding flies". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 17 (3): 263–271. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2915.2003.00430.x. PMID 12941010. S2CID 2459425.

- ^ Yip, E. C. (17 September 2014). "Ants versus spiders: interference competition between two social predators". Insectes Sociaux. 61 (4): 403–406. doi:10.1007/s00040-014-0368-0. ISSN 1420-9098. S2CID 15558561.

- ^ Marshall, Michael (19 September 2014). "Zoologger: Ants fight dirty in turf war with spiders". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Harmer, S.F.; Shipley, A.E. (1899). The Cambridge natural history. Vol. 6. London: Macmillan and co. p. 173. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.1091. LCCN 05012127//r842. OCLC 559687.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 207.

- ^ Trager 1988, p. 517.

- ^ Wheeler 1933, p. 22.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan K.; Shine, Richard (1992). "To find an ant: trail-following in Australian blindsnakes (Typhlopidae)". Animal Behaviour. 43 (6): 941–948. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(06)80007-2. S2CID 53165253.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan K.; Shine, Richard (18 August 1993). "Dietary Habits of Australian Blindsnakes (Typhlopidae)". Copeia. 1993 (3): 762–770. doi:10.2307/1447239. JSTOR 1447239.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan K.; Shine, Richard (June 1993). "Prey-size selection, gape limitation and predator vulnerability in Australian blindsnakes (Typhlopidae)". Animal Behaviour. 45 (6): 1117–1126. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1136. S2CID 53162363.

- ^ Spencer, Chris P.; Richards, Karen (2009). "Observations on the diet and feeding habits of the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) in Tasmania" (PDF). The Tasmanian Naturalist. 131: 36–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2015.

- ^ Ceurstemont, Sandrine (17 March 2014). "Zoologger: Baby assassin bugs lure in deadly ants". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Bulbert, Matthew W.; Herberstein, Marie Elisabeth; Cassis, Gerasimos (March 2014). "Assassin bug requires dangerous ant prey to bite first". Current Biology. 24 (6): R220 – R221. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.R220B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.006. PMID 24650903.

- ^ Cleland, John B.; Maiden, Joseph H.; Froggatt, Walter W.; Ferguson, Eustace W.; Musson, Charles T. (1918). "The food of Australian birds. An investigation into the character of the stomach and crop contents". Science Bulletin. 15: 1–126. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.26676. LCCN agr18000884. OCLC 12311594. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Murray, E. A.; Carmichael, A. E.; Heraty, J. M. (3 April 2013). "Ancient host shifts followed by host conservatism in a group of ant parasitoids". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1759) 20130495. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0495. JSTOR 23478553. PMC 3619522. PMID 23554396.

- ^ Brues, C. T. (1 March 1919). "A New Chalcid-Fly Parasitic on the Australian Bull-Dog Ant". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 12 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1093/aesa/12.1.13.

- ^ a b Crosland, Michael W. J. (1 May 1988). "Effect of a Gregarine Parasite on the Color of Myrmecia pilosula (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 81 (3): 481–484. doi:10.1093/aesa/81.3.481.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998, p. 48.

- ^ Moore, Janice (2002). Parasites and the Behavior of Animals (Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution) (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-514653-0.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998, p. 294.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998, p. 296.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998, p. 310.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998, p. 301.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 447.

- ^ Dumpert, Klaus (1981). The social biology of ants. Boston: Pitman Advanced Pub. Program. pp. 134, 184. ISBN 978-0-273-08479-2.

- ^ Braby, Michael F. (2004). The complete field guide to butterflies of Australia. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-64-309027-9.

- ^ Stein, R.C.; Medhurst, R. (2000). "The toxicology of Myrmecia nigrocincta, an Australian ant". British Homoeopathic Journal. 89 (4): 195–197. doi:10.1038/sj.bhj.5800404. PMID 11055778.

- ^ Gordon, Deborah M. (2010). "5". Ant encounters: interaction networks and colony behavior. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-69-113879-4. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ van Wilgenburg, E; Dang, S; Forti, AL; Koumoundouros, TJ; Ly, A; Elgar, MA (September 2007). "An absence of aggression between non-nestmates in the bull ant Myrmecia nigriceps". Die Naturwissenschaften. 94 (9): 787–90. Bibcode:2007NW.....94..787V. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0255-x. PMID 17458525. S2CID 2271439.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 464.

- ^ Shattuck, Steven O.; Barnett, Natalie J. (1999). Australian Ants: Their Biology and Identification. Vol. 3. Collingwood, Vic: CSIRO Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-643-06659-5.

- ^ Hermann, Henry R. (1982). Social Insects Volume 3. Oxford: Elsevier Science. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-12-342203-3.

- ^ Loveridge, A. (1934). "Australian reptiles in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massachusetts". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 77: 243–283. ISSN 0027-4100. LCCN 12032997//r87. OCLC 1641426. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Wheeler 1933, p. 23.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 479.

- ^ "Frogs that Live with Bull Ants. Nature Studies at Manjimup". The Daily News. Perth, WA: National Library of Australia. 13 December 1935. p. 6. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 183.

- ^ Hadlington, Phillip W.; Beck, Louise (1996). Australian Termites and Other Common Timber Pests. UNSW Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-86-840399-1.

- ^ a b Wheeler 1933, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Qian, Z.Q.; Schlüns, H.; Schlick-Steiner, B.C.; Steiner, F.M.; Robson, S.K.; Schlüns, E.A.; Crozier, R.H. (September 2011). "Intraspecific support for the polygyny-vs.-polyandry hypothesis in the bulldog ant Myrmecia brevinoda". Molecular Ecology. 20 (17): 3681–91. Bibcode:2011MolEc..20.3681Q. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05195.x. PMID 21790819. S2CID 5320809.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 422.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 145.